Abstract

Background

Cases of immune complex vasculitis have been reported following COVID-19 infections; so far none in association with novel mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination. This case report describes a cutaneous immune complex vasculitis after vaccination with BNT162b2.

Case presentation

A 76-year old male with liver cirrhosis developed an immune complex vasculitis 12 days after the second injection of BNT162b2. On physical examination, the patient presented with pruritic purpuric macules on hands and feet, flexor and extensor parts of both legs and thighs and lower abdomen, and bloody diarrhoea. Laboratory testing showed elevated inflammatory markers. After short treatment with oral steroids all clinical manifestations and laboratory findings resolved.

Conclusions

An increasing number of clinical manifestations have been attributed to COVID-19 infection and vaccination. This is the first written report of immune complex vasculitis after vaccination with BNT162b2. We present our case report and a discussion in the light of type three hypersensitivity reaction.

Keywords: Immune complex vasculitis, COVID-19 vaccination, Type three hypersensitivity, BNT162b2, Case report

Background

Patients infected with the novel corona virus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) prominently present with respiratory and thromboembolic complications. High infectivity and high mortality rates of this disease have lead—so far—to an incomparable fatal pandemic outbreak [1]. Shortly after the first description of COVID-19 in Wuhan, Hubei, China in December 2019, scientists started with the development of vaccines as a primary intervention strategy to control coronavirus transmission and infection [2]. Within a year, different vaccines have been developed to induce immunity in humans [3]. One of the earliest approved vaccines was the mRNA-based vaccine BNT162b2 [4]. By now, there have already been more than 1 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses administered worldwide [5]. Adverse events following COVID-19 vaccination mainly consist of typical vaccine related symptoms, such as pain at injection side, chills, fever, arthralgia, myalgia and headache [6]. We report of a patient who developed an immune complex vasculitis after vaccination with BNT162b2.

Case presentation

A 76-year old Caucasian male with a history of compensated alcoholic liver cirrhosis, NYHA II heart failure, gastrectomy after gastroesophageal junction cancer and prostatectomy after prostate cancer and indwelling suprapubic catheter noticed lesions on hands and feet. Due to progressive pruritus and swelling, he shortly presented in our outpatient clinic of the Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Frankfurt. Physical examination revealed symmetric distal limb swelling, and a purpuric rash with palpable maculae on extensor and flexor parts of both hands, legs and thighs reaching up to the lower abdomen (Fig. 1). The smallest purpura lesions were a few millimetres in size and confluent up to centimetres in size. The lesions persisted on diascopy. Upon presentation, the patient denied symptoms of fever, dyspnoea, arthralgia or anuria, but he reported of melaena and diarrhoea the day before. The patient had no history of allergic predispositions or systemic autoimmune diseases. He denied to have started any new medication recently or any changing in alimentary habits. Yet, the patient reported that 12 days ago he received his second mRNA-based vaccination for COVID-19 with BNT162b2. Interestingly, the described skin findings were not seen on his last regular visit 2 days before the second vaccination. After his first vaccination with BNT162b2 6 weeks earlier, he had experienced significant vaccine related myalgia, fever (39.5 °C), hoarseness and fatigue, yet no skin related adverse events had occurred. Before that, he had never experienced any adverse events on previous vaccinations including influenza, herpes zoster or pneumococcal vaccinations.

Fig. 1.

A–D Symmetric distal limb swelling and palpable purpuric confluent macules on extensor (A) and flexor (B) parts of both hands, legs (C) and thighs (D). Purpuric maculae ranging from 2 mm to few centimetres by confluence

Laboratory findings revealed elevated blood sedimentations rate, interleukin-6 levels and C-reactive protein levels. In addition, signs of discrete haemolysis and elevated ammonium levels could be detected. Known moderate micro-erythruria and leukocyturia did not worsen, but stool tests on occult blood was positive and stool calprotectin levels were moderately elevated. Virological tests on human herpes viruses and further human pathogenic viruses showed no new reactivation or infection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient’s laboratory parameters

| Parameter | 2 days before 2nd vaccination | 12 days after 2nd vaccination | 5 days later on prednisolone | Normal range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood results | ||||

| CRP (mg/dl) | 2.09 | 8.69 | < 0.50 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.82 | 0.97 | 1.43 | 0.70–1.20 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 3.5–5.2 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.7 | < 1.4 |

| Direct bilirubin /mg/dl) | 0.8 | 0.4 | < 0.3 | |

| ASAT (U/l) | 47 | 36 | 51 | < 40 |

| ALAT (U/l) | 38 | 25 | 37 | < 50 |

| GGT (U/l) | 31 | 44 | 69 | < 50 |

| LDH (U/l) | 205 | 211 | 223 | < 248 |

| CK (U/l) | 85 | 108 | < 190 | |

| Lactate (mg/dl) | 16.3 | 4.5–20.0 | ||

| ESR (mm/h) | 42 | 19 | < 20 | |

| PCT (ng/ml) | 0.29 | < 0.50 | ||

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 104.0 | 26.6 | < 7.0 | |

| Leucocytes (/nl) | 4.57 | 5.87 | 6.01 | 3.92–9.81 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.6 | 11.3 | 10.1 | 13.5–17.5 |

| Platelets (/nl) | 141 | 114 | 133 | 146–328 |

| INR | 1.19 | 1.23 | 1.26 | 0.85–1.27 |

| IgG (mg/dl) | 1567 | 1549 | 1364 | 700–1600 |

| C3c (mg/dl) | 87 | 90–180 | ||

| C4 (mg/dl) | 16.1 | 10.0–40.0 | ||

| ANA | 1:80 | < 1:80 | ||

| c-ANCA (IFT) | Negative | Negative | ||

| p-ANCA (IFT) | Negative | Negative | ||

| c-ANCA (PR3) EILSA | Negative | Negative | ||

| p-ANCA (MPO) ELISA | Negative | Negative | ||

| Urine results | ||||

| Leukocytes (/µl) | 350 | 447 | < 10 | |

| Erythrocytes (/µl) | 11 | 30 | < 5 | |

| Stool results | ||||

| Calprotectin (µg/g) | 115 | < 50 | ||

| EDN (ng/ml) | 802 | < 1700 | ||

| iFOBT | Positive | Negative | ||

| Stool pathogens | Negative | |||

| Virology | ||||

| CMV-DNA | Negative | |||

| EBV-DNA | Negative | |||

| HSV-1 IgG | positive 17.1 index | |||

| HSV-2 IgG | Negative | |||

| HHV-6 IgG | Negative | |||

| HHV-6 IgM | Negative | |||

| VZV IgG | Positive 2727 mE/ml | |||

| VZV IgM | Negative | |||

| Parvovirus B19 IgG | Positive 10 index | |||

| Parvovirus B19 IgM | Negative | |||

| Microbiology | ||||

| Treponema pallidum screening | Negative | |||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgG | Negative | |||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM | Negative | |||

Newly elevated laboratory results and dynamics are presented in bold

CRP c-reactive-protein, ASAT aspartate transferase, ALAT alanine transferase, GGT gamma glutamyl transferase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, CK creatinine kinase, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, PCT procalcitonin, IL interleukin, INR international normalized ratio, IgG immunoglobulin G, C3C complement component 3, C4 complement component 4, ANA antinuclear antibody, ANCA antinuclear cytoplasm antibody, EDN eosinophil-derived antitoxin, iFOBT immunochemical faecal occult blood test, CMV cytomegalovirus, DNA desoxyribonucleic acid, Ig immunoglobulin, EBV Ebstein-Barr-virus, HSV herpes simplex virus, HHV human herpes virus, VZV varicella zoster virus

In consultation with our senior physician specialist from the Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, the correlation of the clinical presentation, laboratory findings and recent COVID-19 vaccine, we established the diagnosis of cutaneous and gastrointestinal immune complex vasculitis probably triggered by BNT162b2 injection. The patient was started on 40 mg oral prednisolone once daily. Shortly after, the patient reported of symptom relief. On the 5th day of therapy, he already presented with rapid resolving skin lesions (Fig. 2). At follow-up visit 23 days after BNT162b injection, we could observe small remaining scabs on both lower legs and the patient described remaining hyperalgesia while touching these lesions. Oedema, pruritus and purpuric lesions fully resolved and inflammation markers decreased. Stool formation and colour returned to normal. Prednisolone was quickly tapered and stopped.

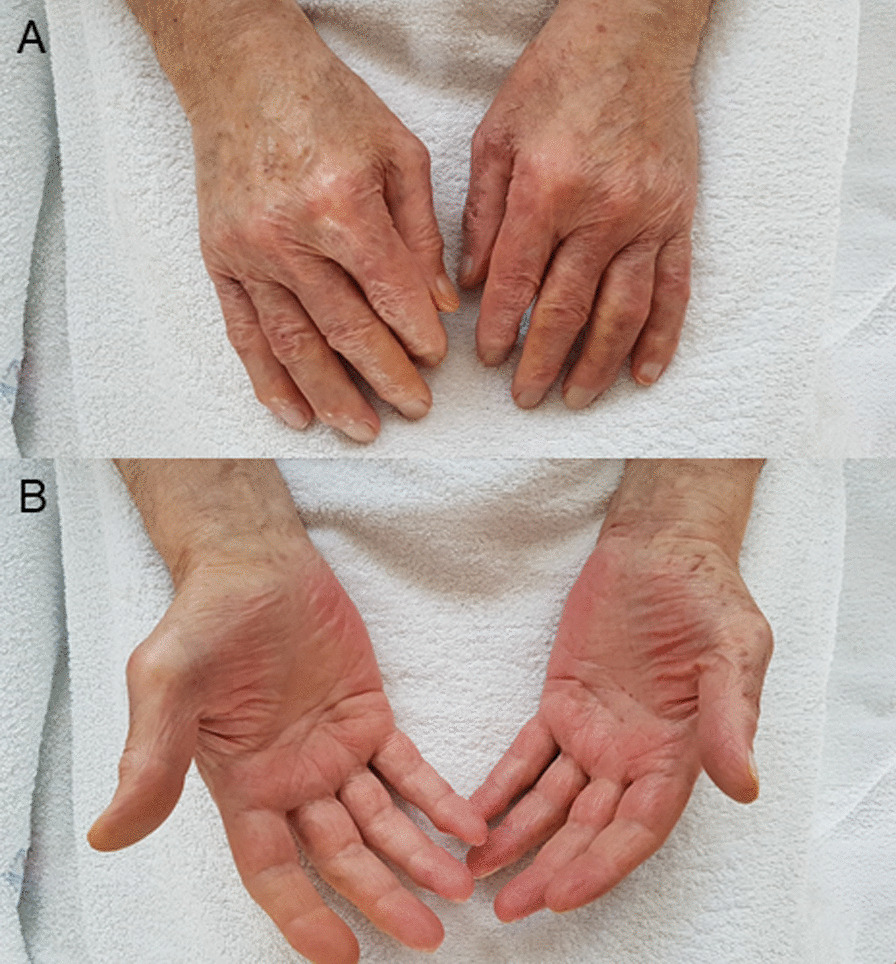

Fig. 2.

A, B Resolved skin lesions of extensor (A) and flexor (B) parts of both hands on the fifth day of steroid therapy

Discussion and conclusions

Despite of rapid pulmonary failure, vascular complications due to coagulopathy, endotheliopathy and vasculitis significantly contribute to the high mortality rates of patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV2) [7]. Recent observations also showed that infections with SARS-CoV-2 may go along with mild to fulminant dermal diseases [8]. Until now, data on pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of COVID-19 support the hypothesis of three distinct phases of the disease: viral phase, immunological phase and haemo-vascular phase [9, 10]. In October 2020 Manzo discussed COVID-19 as a trigger for an immune complex hypersensitivity reaction [11]. He highlighted the significant antigen excess in the second phase of COVID-19 disease that may lead to the formation of soluble antigen-antibody immune complexes, which cannot be removed by phagocytes anymore. These may settle and persist in tissue places, e.g., skin where they can induce persistent inflammation. In general, multiple infectious diseases are known to be facultative triggers of immune complex diseases, e.g., beta-hemolytic streptococcal bacteria that precede purpura Schoenlein-Henloch disease in pediatric patients [12], an example of type three hypersensitivity. Interestingly, a recent letter to the editor of Roncati et al. discussed COVID-19 preceding a type three hypersensitivity vasculitis by inducing a severe inflammatory state by an interleukin-6 mediated cytokine release syndrome [13].

As vaccines are supposed to induce antigen-antibody reactions, novel COVID-19 vaccines mediated by the SARS-CoV2-spike-protein may trigger similar pathogenic effects. So far, cutaneous immune complex vasculitis have been seen in older patients after receiving seasonal influenza vaccinations [14]. Until now, data on the range of side effects of the novel COVID-19 vaccines are rare, but especially severe thrombotic [15] and anaphylactic reactions [16] drew scientific and general society’s’ attention. Recently, Bomback et al. published a summary of reported glomerular diseases after COVID-19 vaccination, including ten cases of IgA nephropathies [17]. MRNA-based vaccines have never been licensed for application in humans before this pandemic. Therefore, effects and side effects of BNT162b2 and its related agents are of great scientific interest. In current literature safety and efficacy of BNT162b2 was similar to other viral vaccines [18].

Our case report is the first to describe a cutaneous and gastrointestinal immune complex vasculitis after a mRNA-based vaccination with BNT162b2, in a cirrhotic patient without any history of autoimmune or vasculitis predisposition. Immune complex related extrahepatic conditions can be seen in patients with chronic liver disease. However, the majority of these cases are described in patients with liver disease due to hepatitis C or B infection [19, 20] or florid bacterial infection [21]. One can assume that a chronic liver disease may have precipitating effects of the deposition of immune complexes with defective liver metabolism of IgA circulating immune complexes, but we interpret the mRNA-vaccination as the main trigger of this phenomenon in our patient.

In general, most cases of cutaneous immune complex vasculitis are self-limited [22]. As our patient presented with pronounced skin involvement, additional gastrointestinal inflammation and bleeding signs we decided to treat him with oral anti-inflammatory steroids. Thereby, we achieved fast relief and restoration of our patient’s health. In patients with severe organ failure, strong immunosuppressive therapy and plasmapheresis may be necessary [23].

We acknowledge that the link between BNT162b2-vaccine and cutaneous and gastrointestinal immune-complex vasculitis cannot be confirmed by a single case. However, our theory is supported by: (1) the fact that the patient did not have any history of vasculitis before—and no dermal lesion was seen 2 days prior the second vaccination, (2) the suitable time span of 12 days between exposition and appearance of type three hypersensitivity reaction without any hints of an alternative cause—no changes in medication, alimentary habits or sign of another infection (3) interleukin-6 mediated inflammatory response and (4) data on COVID-19 infections that trigger immune complex vasculitis.

Worldwide, more than one billion COVID-19 vaccines doses have been injected to control the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [5]. Among these, novel mRNA-based vaccines are administered on large scale for the first time in history. So far, serious adverse events reported with mRNA-vaccines, especially BNT162b2 are rare and efficacy rates are high [18]. However, clinical trials will not be able to detect rare clinical side effects. We are the first to describe the event of an immune complex vasculitis in a patient with liver cirrhosis without known predispositions for type 3 hypersensitivity. The purpose of this case report is to raise awareness of possible side effects in healthcare professionals in the so far world’s fastest and biggest vaccination program. We aim to highlight the importance of further scientific and clinical vigilance and surveillance.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the cooperation of the patient whose condition was reported. This article is published with written consent of the patient.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Corona virus disease of 2019

- SARS-CoV2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2

Authors’ contributions

VTM, VK, MMM and SZ were directly involved in the patients’ primary care as gastroenterological physicians. FO was the consulting dermatologist in this case. VTM, VK, MMM, FO and SZ interpreted and discussed the patients’ condition and decided on clinical management. Data collection, statistical analysis and data preparation were done by VTM. VTM prepared the manuscript. VTM and MMM prepared the figures. All authors interpreted data. VTM, VK, MMM, FO and SZ revised the manuscript including further literature search. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. More information are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Identifying/confidential patient data will not be shared.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent to analyse and report data was obtained from the patient of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Consent to publication

Written informed consent to publish this case report was obtained from the patient. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal. All authors agreed.

Competing interests

VTM: None; VK: None; MMM: None; FO: None; SZ: None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of V The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):536–44. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Coronavirus diseaese (COVID-19) pandemic. (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019, Last accessed: 05/20/2021).

- 3.Yadav T, Srivastava N, Mishra G, et al. Recombinant vaccines for COVID-19. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(12):2905–12. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1820808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamb YN. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine first approval. Drugs. 2021;81(4):495–501. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01480-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John Hopkins University & Medicine - Corona Virus Resource Center. (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/, Last accessed 05/20/2021).

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Safety of COVID-19 Vaccination. (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/safety-of-vaccines.html, Last accessed 05/20/2021).

- 7.Iba T, Connors JM, Levy JH. The coagulopathy, endotheliopathy, and vasculitis of COVID-19. Inflamm Res. 2020;69(12):1181–9. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01401-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galvan Casas C, Catala A, Carretero Hernandez G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(1):71–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gautret P, Million M, Jarrot PA, et al. Natural history of COVID-19 and therapeutic options. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16(12):1159–84. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2021.1847640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohamadian M, Chiti H, Shoghli A, Biglari S, Parsamanesh N, Esmaeilzadeh A. COVID-19: virology, biology and novel laboratory diagnosis. J Gene Med. 2021;23(2):e3303. doi: 10.1002/jgm.3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manzo G. COVID-19 as an immune complex hypersensitivity in antigen excess conditions: theoretical pathogenetic process and suggestions for potential therapeutic interventions. Front Immunol. 2020;11:566000. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.566000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.al-Sheyyab M, Batieha A, el-Shanti H, Daoud A. Henoch-Schonlein purpura and streptococcal infection: a prospective case-control study. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1999;19(3):253–5. doi: 10.1080/02724939992329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roncati L, Ligabue G, Fabbiani L, et al. Type 3 hypersensitivity in COVID-19 vasculitis. Clin Immunol. 2020;217:108487. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen SX, Cohen PR. Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis following influenza vaccination in older adults: report of bullous purpura in an octogenarian after influenza vaccine administration. Cureus. 2018;10(3):e2323. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf ME, Luz B, Niehaus L, Bhogal P, Bazner H, Henkes H. Thrombocytopenia and intracranial venous sinus thrombosis after “COVID-19 vaccine AstraZeneca” exposure. J Clin Med 2021;10(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Team CC-R, Food DA. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine-United States, December 14–23, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(2):46–51. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7002e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bomback AS, Kudose S, D’Agati VD. De novo and relapsing glomerular diseases after COVID-19 vaccination: what do we know so far? Am J Kidney Dis 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grigorescu I, Dumitrascu DL. Spontaneous and antiviral-induced cutaneous lesions in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(42):15860–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko HM, Hernandez-Prera JC, Zhu H, et al. Morphologic features of extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:740138. doi: 10.1155/2012/740138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta N, Kim J, Njei B. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and Henoch-Schonlein purpura in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:340894. doi: 10.1155/2015/340894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radic M, Martinovic Kaliterna D, Radic J. Drug-induced vasculitis: a clinical and pathological review. Neth J Med. 2012;70(1):12–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goeser MR, Laniosz V, Wetter DA. A practical approach to the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15(4):299–306. doi: 10.1007/s40257-014-0076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. More information are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Identifying/confidential patient data will not be shared.