This systematic review and meta-analysis examines the association of hypothyroidism (subclinical or overt) with depression.

Key Points

Question

Is there an association of hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity with depression?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 25 studies including 348 014 participants, there was a moderate association of overt, and less so of subclinical, hypothyroidism with clinical depression; this association is stronger in female than in male individuals. A statistically significant association of verified thyroid peroxidase antibodies positivity and clinical depression was not found.

Meaning

A strong connection between hypothyroidism and depression was not evident in this analysis; however, a possible dose-effect relationship, especially in female individuals, should be investigated further.

Abstract

Importance

Hypothyroidism is considered a cause of or a strong risk factor for depression, but recent studies provide conflicting evidence regarding the existence and the extent of the association. It is also unclear whether the link is largely due to subsyndromal depression or holds true for clinical depression.

Objective

To estimate the association of hypothyroidism and clinical depression in the general population.

Data Sources

PubMed, PsycINFO, and Embase databases were searched from inception until May 2020 for studies on the association of hypothyroidism and clinical depression.

Study Selection

Two reviewers independently selected epidemiologic and population-based studies that provided laboratory or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems diagnoses of hypothyroidism and diagnoses of depression according to operationalized criteria (eg, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) or cutoffs in established rating scales.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers independently extracted data and evaluated studies based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Summary odds ratios (OR) were calculated in random-effects meta-analyses.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prespecified coprimary outcomes were the association of clinical depression with either hypothyroidism or autoimmunity.

Results

Of 4350 articles screened, 25 studies were selected for meta-analysis, including 348 014 participants. Hypothyroidism and clinical depression were associated (OR, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.08-1.57]), while the OR for autoimmunity was inconclusive (1.24 [95% CI, 0.89-1.74]). Subgroup analyses revealed a stronger association with overt than with subclinical hypothyroidism, with ORs of 1.77 (95% CI, 1.13-2.77) and 1.13 (95% CI, 1.01-1.28), respectively. Sensitivity analyses resulted in more conservative estimates. In a post hoc analysis, the association was confirmed in female individuals (OR, 1.48 [95% CI, 1.18-1.85]) but not in male individuals (OR, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.40-1.25]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the effect size for the association between hypothyroidism and clinical depression was considerably lower than previously assumed, and the modest association was possibly restricted to overt hypothyroidism and female individuals. Autoimmunity alone may not be the driving factor in this comorbidity.

Introduction

The symptoms of hypothyroidism and depression partly overlap, but for decades, a more specific link between both disorders has been discussed.1 Neurobiological research has uncovered some mechanisms of thyroid hormones in the brain, providing possible explanations for an interaction with mood.2,3 Also, immunologic processes may provide a link between autoimmune thyroiditis and depression.4,5

A 2018 meta-analysis6 reported a substantial association of subclinical and clinical depression with hypothyroid autoimmunity. With an odds ratio (OR) of 3.31, Siegmann et al7 estimated that each year, more than 20% of patients with autoimmune thyroiditis experience depression. This meta-analysis has been criticized, for example, for its combination of population-based studies with results from outpatient clinics, with their bias toward more severely affected patients.8,9 Since the authors associated thyroid status with any change of depression scores, including and especially changes below cutoffs for clinically relevant depression, the practical significance of the results is uncertain. In contrast, another meta-analysis10 reported only a weak, nonsignificant association of hypothyroidism and depression (OR, 1.24). However, while this study is an individual patient data meta-analysis, it was based on only 6 studies and was restricted to subclinical hypothyroidism.

As a result, the existence and the extent of an association between hypothyroidism and clinical depression remains unclear. In addition, if there were such an association, it is unknown whether hypothyroidism or autoimmunity is the driving force. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies presenting data on hypothyroidism (subclinical or overt) and clinical depression. To reduce selection bias, we restricted the meta-analysis to epidemiologic and population-based studies.

Methods

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020164791). Its reporting is based on the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.11

Literature Search and Data Extraction

We conducted a systematic search in MEDLINE and PubMed Central via PubMed, in PsycINFO via EBSCOhost, and in Embase to identify epidemiologic and population-based studies on the association of hypothyroidism with the occurrence of depression from inception to May 4, 2020. We combined generic terms for depression, hypothyroidism, and population-based study settings. Search terms and history are specified in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Selection Criteria

Cohort and cross-sectional studies were included. The study population was representative of the general population. Studies were population based and not primarily conducted with patients with thyroid or mood disorders in a medical setting. Studies conducted in broad and diverse populations (eg, civil servants) not suggestive of bias were eligible. Thyroid disorders leading to or representing hypothyroidism, either subclinical or overt, autoimmune disorders (eg, Hashimoto thyroiditis), as diagnosed by established laboratory methods or drawn from registers including hospital data if reliability of diagnoses was documented. Laboratory criteria had to be specified by the authors. For overt hypothyroidism, criteria needed to consist of at least 1 elevated thyrotropin and 1 lowered free thyroxine measurement. Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined by increased thyrotropin, without evidence of lowered free thyroxine. Thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody positivity had to be assessed by at least 1 measurement of TPO antibodies above a threshold prespecified by the authors. Outcomes included clinically significant depression, either defined as a major depressive disorder diagnosis according to established diagnostic systems, eg, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) (DSM-IV), or an above-threshold score in established psychopathology rating scales for depression,12 with thresholds prespecified by the authors. Diagnoses could originate with assessment rating scales, standardized interviews (eg, World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview), or from registers including hospital data if reliability of diagnoses was documented.

Case-control studies were excluded. Two authors (H.B. and B.I.) independently screened titles and abstracts retrieved in the literature search. We did not exclude gray literature and applied no language or date restrictions. Bibliographies of all articles eventually included were hand searched. Two raters (H.B. and B.I.) independently read full texts of all articles potentially eligible. Data from included studies were extracted independently by 2 authors (H.B. and B.I.) using an Excel-based standardized data extraction form (Microsoft) in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook. All disagreements were solved by consensus or discussion with the senior author (C.B.).

All studies included were rated independently by 2 authors (H.B. and B.I.) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing risk of bias, using the adaptations for cohort13 and cross-sectional studies.14 Studies were rated as carrying an overall low risk of bias when falling into the highest Newcastle-Ottawa Scale category, ie, receiving all or all but 1 star in the rating system.

Data Analysis

Primary Outcome and Analysis

The primary analysis consists of a 2-part investigation: we measured the association of depression with (1) hypothyroidism and (2) thyroid autoimmunity, expressed as ORs with 95% CIs. We compared the occurrence of clinical depression in people with vs without hypothyroidism/autoimmunity. If studies reported the observed effect as either a risk ratio or hazard ratio, we transformed these effect sizes into ORs. If studies reported adjusted effect sizes, we included those with the least comprehensive adjustment to be as coherent as possible with unadjusted effect sizes. The first part of the primary analysis included all studies reporting results for overt or subclinical hypothyroidism. The other part of the analysis included all studies reporting associations of TPO antibody positivity. Calculations and formulae are listed in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Subgroup Analyses

We subdivided hypothyroidism into subclinical and overt hypothyroidism, as defined above, and stratified our primary analyses by sex, risk of bias, intake of thyroid medication, a core group of strictly population-based studies, and assessment of depression.

Post hoc Analyses

Hypothyroidism and depression affect more female than male individuals, but it has not been established so far whether depression also occurs more often in female individuals among patients diagnosed with hypothyroidism. Therefore, we further explored sex-specific results found in subgroup analyses by analyzing studies reporting results on both sexes differently. We also stratified our analyses by age, comparing studies on older populations (minimum age ≥60 years) with studies on individuals of all ages.

Data Synthesis

Owing to differences in study design and settings, we used random-effects analyses (DerSimonian & Laird), which assume that effects vary according to the specifics of a study rather than 1 true effect underlying all studies.15 For primary outcomes, we also report prediction intervals to account for the heterogeneity between studies.16 Statistical heterogeneity, which describes the variation in results between studies, is reported as I2 statistic and as tau, the standard deviation of the effect estimate. We assessed publication bias in funnel plots and Egger test17 and estimated the role of missing studies in trim-and-fill-analyses.18 A leave-1-out analysis was conducted if forest plots indicated a disproportionate influence of single studies in calculating summary ORs. We used the software package Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 (Biostat) as well as R software (R Foundation), including the R packages meta19 and metafor.20 Two-sided P values were significant at .05.

Results

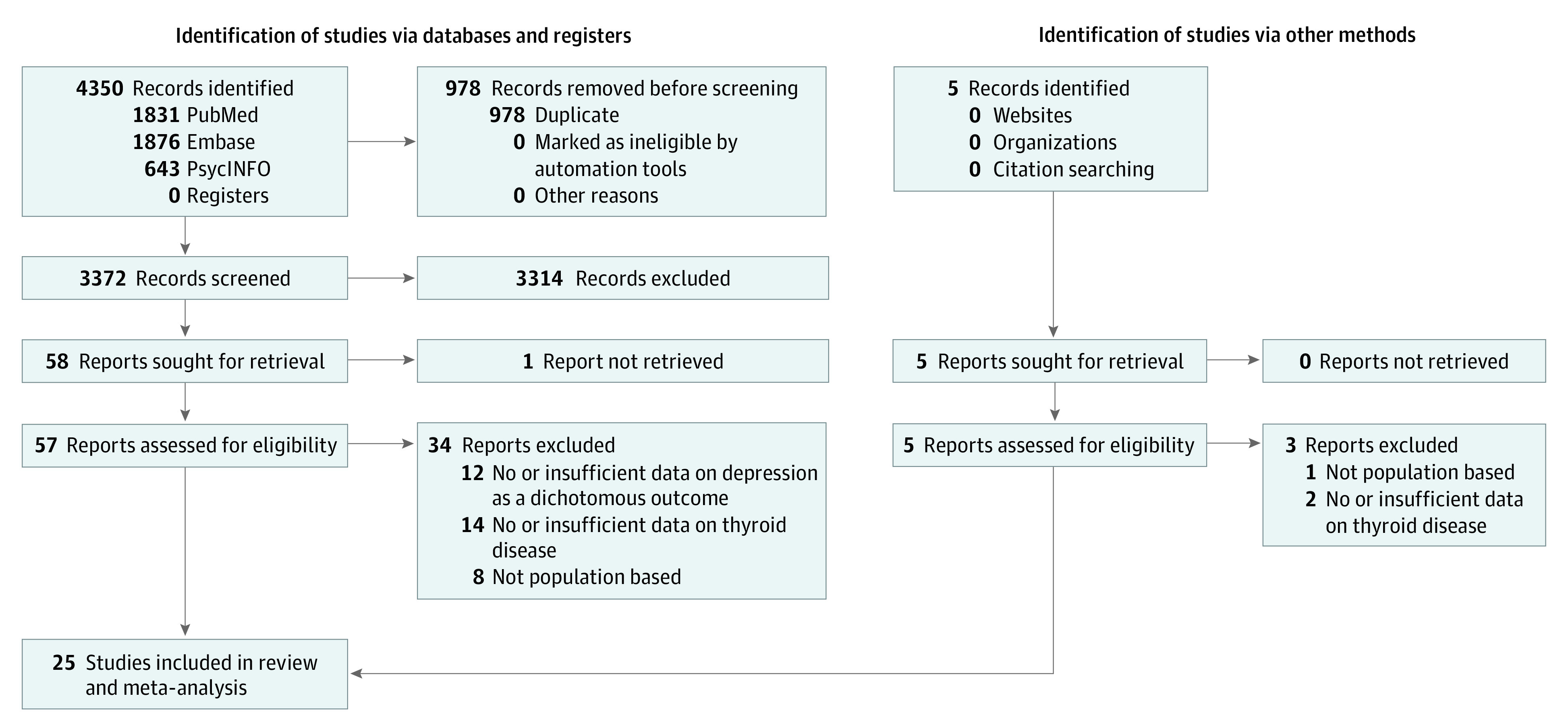

After screening 4350 articles and excluding duplicates, we reviewed 62 in full text. Of those, 25 articles21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45 were included in this study (Figure 1). Nine studies provided data on individuals with overt hypothyroidism, 17 on individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism, and 9 on individuals with thyroid autoimmunity.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Table 1 displays characteristics of all studies: 6 cohort (236 646 of 348 014 participants [68%]) and 19 cross-sectional studies (111 368 [32%]), with 348 014 participants, ranging from 10039 to 131 041.44 The study size weighted mean age of participants was 44.9 years. The overall proportion of female individuals was 53.6%.

Table 1. Characteristics of Studies Included .

| Source | Study type | No. of patients | NOS score | Thyroid disorder | Sex | Age range, y | Assessment of thyroid disorder | Assessment of depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeida et al,21 2011 | Cohort | 3901 | 9a | Subclinical | Male | 69-87 | FT4, TSH | Clinical diagnosisb |

| Benseñor et al,22 2016 | Cross-sectional | 13 221 | 7 | Subclinical | Mixed | 35-74 | FT4, TSH | Clinical diagnosisb |

| Bould et al,23 2012 | Cross-sectional | 325 | 6 | Subclinical | Mixed | 17-74 | FT4, TSH | PHQ-9 |

| Carta et al,24 2004 | Cross-sectional | 222 | 7 | Autoimmunity | Mixed, female, male | ≥18 | TPO-abs | Clinical diagnosisb |

| de Jongh et al,25 2011 | Cross-sectional | 1185 | 7 | Subclinical | Mixed | ≥65 | FT4, TSH | CES-D |

| Delitala et al,26 2016 | Cross-sectional | 3138 | 8 | Autoimmunity | Mixed | NA | TPO-abs | CES-D |

| Engum et al,27 2002 | Cross-sectional | 30 062 | 9a | Overt, subclinical | Mixed | 40-89 | FT4, TSH | HADS-D |

| Engum et al,28 2005 | Cross-sectional | 30 175 | 9a | Autoimmunity | Mixed | 40-84 | TPO-abs | HADS-D |

| Fjaellegaard et al,29 2015 | Cross-sectional | 8214 | 7 | Autoimmunity | Mixed, female, male | ≥20 | FT4, TSH, TPO-abs | Clinical diagnosisb |

| Subclinical | Mixed | |||||||

| Guimarães et al,30 2009 | Cross-sectional | 1249 | 9a | Overt, subclinical | Female | 35-91 | FT4, TSH | PRIME-MD |

| Hong et al,31 2018 | Cross-sectional | 1717 | 8 | Subclinical | Mixed | 19-76 | FT4, TSH | PHQ-9 |

| Ittermann et al,32 2015 | Cohort | 1895 | 8a | Overt, autoimmunity | Mixed | 20-79 | TSH, TPO-abs | Clinical diagnosisb |

| Kim et al,33 2010 | Cross-sectional | 481 | 8 | Subclinical | Mixed | ≥65 | TSH | GMS-B3 |

| Kim et al,34 2018 | Cohort | 92 206 | 8a | Subclinical | Mixed | NA | FT4, TSH | CES-D |

| Kvetny et al,35 2015 | Cross-sectional | 14 502 | 8 | Subclinical | Mixed, female, male | ≥20 | TSH | Clinical diagnosisb |

| Lee et al,36 2019 | Cross-sectional | 1651 | 8 | Autoimmunity | Mixed, female, male | ≥20 | TPO-abs | PHQ-9 |

| Lin et al,37 2016 | Cohort | 6100 | 9a | Overt | Mixed, female, male | ≥20 | Register | Clinical diagnosisb |

| Manciet et al,38 1995 | Cross-sectional | 407 | 7 | Overt, subclinical | Mixed | ≥65 | FT4, TSH | CES-D |

| Maugeri et al,39 1998 | Cross-sectional | 100 | 6 | Overt, subclinical | Mixed | ≥70 | T4, TSH | GDS-30 |

| Medici et al,40 2014 | Cohort | 1503 | 9a | Autoimmunity | Mixed | ≥55 | TPO-abs | Clinical diagnosisb |

| Park et al,41 2010 | Cross-sectional | 918 | 7 | Subclinical | Mixed, female, male | ≥65 | FT4, TSH | Clinical diagnosisb |

| Pop et al,42 1998 | Cross-sectional | 583 | 8 | Overt, subclinical, autoimmunity | Female | 47-54 | FT4, TSH, TPO-abs | EDS |

| Shinkov et al,43 2014 | Cross-sectional | 2312 | 7 | Subclinical | Mixed, female, male | 20-84 | TSH | Zung SDS |

| Thomsen et al,44 2005 | Cohort | 131 041 | 8a | Overt | Mixed | ≥15 | Register | Clinical diagnosisb |

| van de Ven et al,45 2012 | Cross-sectional | 906 | 8 | Overt, subclinical, autoimmunity | Mixed | 50-70 | FT4, TSH | BDI-Ia |

Abbreviations: BDI-Ia, Beck Depression Inventory Ia; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; EDS, Edinburgh Depression Scale; FT4, free thyroxine; GDS-30, Geriatric Depression Scale 30; GMS-B3, Geriatric Mental State Diagnostic Schedule; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NA, not applicable; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; PRIME-MD, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; TPO-abs, thyroid peroxidase antibodies; TSH, thyrotropin; Zung SDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale.

Included in the risk of bias analysis.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders– or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems–conforming diagnosis of depression.

Fifteen studies assessed depressive symptoms using a score. Ten studies reported DSM- and/or ICD-conforming diagnoses of major depressive disorder. Twenty-three studies reported diagnoses of thyroid disorders based on established laboratory methods, and 2 used register data on ICD-based diagnoses, which included laboratory assessments as well. Individuals taking thyroid medication were included in 12 studies. Six cohort and 3 cross-sectional studies had a low risk of bias. Additional data on the included studies can be obtained from eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Primary Analysis

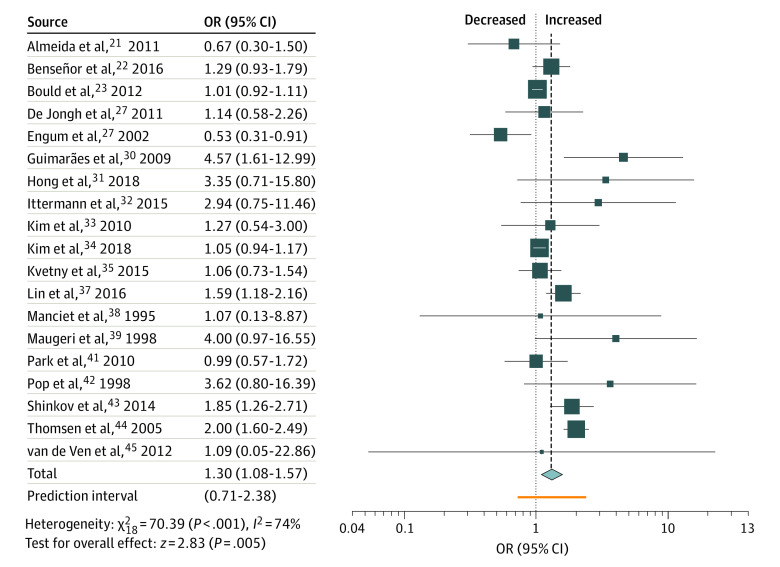

The analysis resulted in an OR of 1.30 (95% CI, 1.08-1.57) for all types of hypothyroidism (Figure 2). Separated in subclinical and overt hypothyroidism ORs were 1.13 (95% CI, 1.01-1.28) and 1.77 (95% CI, 1.13-2.77), respectively (Table 2). In combined analysis, there was a difference between female individuals (OR, 1.62 [95% CI, 1.20-2.19]) and male individuals (OR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.44-1.11]). Strictly population-based studies yielded a moderately stronger association. Cohort design, inclusion of individuals taking thyroid medication, and a DSM- or ICD-conforming diagnosis of depression also resulted in moderately higher associations (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Association of Hypothyroidism and Depression.

OR indicates odds ratio.

Table 2. Main Resultsa.

| Analysis | Hypothyroidism | TPO antibodies positivity | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | OR (95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity | Trim-and-fill analysis | No. of studies | OR (95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity | Trim-and-fill analysis | |||||||

| I2, % | τ | No. of studies | OR (95% CI) | P value for Egger test | I2, % | τ | No. of studies | OR (95% CI) | P value for Egger test | |||||||

| Primary analysis | 19 | 1.30 (1.08-1.57) | .005 | 74 | 0.269 | 5 | 1.17 (0.97-1.41) | .09 | 9 | 1.24 (0.89-1.74) | .20 | 65 | 0.390 | 4 | 0.89 (0.63-1.27) | .02 |

| Overt hypothyroidism | 9 | 1.77 (1.13-2.77) | .01 | 70 | 0.464 | NA | NA | .89 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | 16 | 1.13 (1.01-1.28) | .04 | 45 | 0.125 | 5 | 1.04 (0.90-1.20) | .01 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Low risk of bias | 7 | 1.33 (0.90-1.97) | .15 | 88 | 0.432 | NA | NA | .57 | 3 | 0.87 (0.64-1.20) | .41 | 12 | 0.133 | 2 | 0.79 (0.56-1.11) | .11 |

| Post hoc female | 4 | 1.48 (1.18-1.85) | .001 | 13 | 0.085 | NA | NA | .35 | 3 | 0.99 (0.44-2.20) | .98 | 72 | 0.596 | NA | NA | .21 |

| Post hoc male | 4 | 0.71 (0.40-1.25) | .23 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | .66 | 3 | 0.88 (0.26-3.06) | .85 | 56 | 0.821 | NA | NA | .30 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; TPO, thyroid peroxidase.

Associations are reported as ORs and 95% CIs. Egger test P value is reported as 2-sided; less than .10 indicates funnel plot asymmetry and the possibility of reporting bias.

Small study associations are possible (P = .09) and adding 5 studies in trim and fill lowered the OR to 1.17 (95% CI, 0.97-1.41). Egger test (P = .012) was also positive in studies on subclinical hypothyroidism, and after adding 6 studies in trim and fill, the OR was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.9-1.20). In studies on overt hypothyroidism, no small study associations were detected (Table 2).

In primary leave-1-out analysis, omitting the study of Thomsen et al44 reduced the association to 1.22 (95% CI, 1.03-1.43). Similarly, removing the study of Shinkov et al43 lowered the association of subclinical hypothyroidism to 1.07 (95% CI, 0.97-1.17). In overt hypothyroidism, removal of studies by Engum et al27 and Thomsen et al44 increased ORs to 1.93 (95% CI, 1.63-2.30) and 1.84 (95% CI, 0.97-3.47), respectively. Conversely, removal of Guimaraes et al30 decreased the association to 1.58 (95% CI, 1.00-2.50).

Risk of bias analyses showed decreased associations throughout (Table 2), and subclinical hypothyroidism was no longer associated with clinical depression in risk of bias analyses. As an exception, our primary analysis on hypothyroidism yielded slightly increased associations with studies with a low risk of bias (OR, 1.33 [95% CI, 0.90-1.97]), but statistical significance was lost.

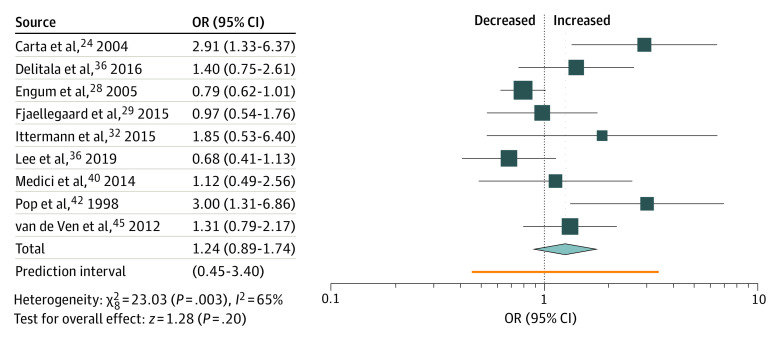

Individuals with TPO antibodies had a nominally increased OR of 1.24 (95% CI, 0.89-1.74) (Table 2 and Figure 3). Subgroup analyses revealed a nonsignificant difference in associations between male and female individuals. Stratification for intake of thyroid medication and DSM- or ICD-conforming diagnoses of depression yielded slightly stronger associations (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Association of Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies Positivity and Depression.

OR indicates odds ratio.

Adjustment for small study effects (Egger test = 0.022) by 4 added studies reversed the association (OR, 0.89 [95% CI, 0.63-1.27]), as did the analysis restricted to studies carrying a low risk of bias (Table 2). In addition, a leave-1-out-analysis revealed that Carta et al24 disproportionately increased the effect size (exclusion led to an OR of 1.11 [95% CI, 0.82-1.51]).

We calculated an I2 of 65% in the analysis on TPO antibodies positivity, which was reduced when we restricted the calculation to studies with a low risk of bias. Eliminating studies by Carta et al24 or Engum et al28 each reduced I2 by 10%. In the analysis on hypothyroidism, I2 amounted to 74% and did not decrease with limiting the calculation to studies with low risk of bias. However, it was brought down to 60% when leaving out Thomsen et al.44 Among investigations on subclinical hypothyroidism, heterogeneity was lower (45%). Here, removal of the study by Shinkov et al43 further decreased I2 to 26%. In overt hypothyroidism, heterogeneity (70%) was reduced to 0% after omitting the study by Engum et al.27

None of these analyses substantially changed the summary ORs (Table 2; eTable 2 in the Supplement). Tau, another measurement of heterogeneity, was much lower than the effect estimate in almost all analyses

Post hoc Analyses

To reduce bias, we restricted the analysis to studies comparing men and women. For hypothyroidism, women (OR, 1.48 [95% CI, 1.18-1.85]) showed a higher OR than men (OR, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.40-1.25]). There was no such contrast in autoimmunity studies (Table 2).

With regard to hypothyroidism, studies on older populations reported smaller associations than studies on all ages. There were no such studies investigating TPO antibodies positivity (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Our analysis yielded 3 main results. (1) There is a moderate association of overt, and less so of subclinical, hypothyroidism with clinical depression. (2) There is no statistically significant association of verified TPO antibodies positivity with clinical depression. (3) We found a stronger association of hypothyroidism and clinical depression in female individuals than in male individuals.

Hypothyroidism and Depression

Hypothyroidism and clinical depression are associated with an OR of 1.3 and even smaller when only studies with a low risk of bias are included or if possible reporting bias is taken into account. However, there is evidence for a dose-effect relationship, as indicated by an OR of about 1.1 for subclinical and 1.8 for overt hypothyroidism.

The extent of the association is weaker than what sometimes seems to be assumed in clinical practice and, in part, in psychiatric research. It is also at odds with work by Loh et al,46 who estimated the association of subclinical hypothyroidism and depression to be 2.35 in their meta-analysis. However, they analyzed a lower number of studies (n = 15) and mixed case-control and cohort studies. In our opinion, the divide between case-control and cohort studies needs to be strongly emphasized.8 Case-control studies are frequently conducted in tertiary care centers with a preponderance of severe cases, not representative of the general population. To avoid the bias inherent to case-control studies, Wildisen et al10 carried out a meta-analysis of individual patient data ascertained in 6 population-based studies. In contrasting subclinically hypothyroid and euthyroid probands, they estimated that the former scored a mean of 0.29 (95% CI, −0.17 to 0.76) points higher on the Beck Depression Inventory, less than 0.5% of the scale width,47 irrelevant in the view of the authors.

In comparison with the continuous measurement of depression by Wildisen et al,10 we focused on a dichotomous outcome: clinically relevant depression as defined by study authors. Statistically, it is advisable to use continuous outcomes. However, with continuous measures, such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, statistically significant differences between individuals with and without hypothyroidism can be clinically unimportant as long as differences remain below pathological limits. In this sense, using continuous end points runs the risk of creating false-positive results.

Nevertheless, our results are in line with Wildisen et al.10 Zhao et al48 estimated a higher association of subclinical hypothyroidism and depression (OR, 1.75 [95% CI, 0.97-3.17]), although of borderline significance. Of note, they included fewer and smaller studies and measured higher heterogeneity, indicating the preliminary nature of their result.

Autoimmunity and Depression

We did not find a statistically significant association of autoimmunity and depression. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis focusing on general population samples with documented TPO antibody status. Our findings are at variance with a recent meta-analysis7 publishing an OR of 3.3. This would be a very strong association, as indicated by the projection by Siegmann et al6 that, annually, more than 20% of patients with autoimmune hypothyroidism experience depression. With our results, the figures are in the 7% to 9% range, barely higher than the population prevalence.49,50 It is worth pointing out the differences between the 2 approaches; in restricting our study to epidemiologic studies, we hope our results are less vulnerable to biases arising from the use of samples from endocrinology or psychiatry clinics. We restricted our analyses to verified TPO antibody positivity, whereas Siegmann et al6 considered hypothyroidism in general a proxy for autoimmunity and included 35 168 individuals as opposed to 47 707 in the present investigation.

In our sample of studies, TPO antibody status was measured in individuals with euthyroidism except for the investigations by Engum et al28 and Pop et al.42 Hence, we excluded both studies in a sensitivity analysis and found that the results still hold; the OR went slightly down to 1.23 (95% CI, 0.87-1.73) without reaching statistical significance.

Our result may in part reflect the preponderance of subclinical hypothyroidism in individuals with TPO antibody positivity, but it may also have bearing on pathophysiological considerations, in particular in view of the negative analyses considering reporting bias, low risk of bias studies, and population-based studies in the strict sense. Possibly, it is not the disturbance of the immune system that explains the comorbidity. Hypothyroidism may work differently. More specific pathways aside, studies conducted by Patten et al51,52 show that, in an unspecific way, many chronic disorders increase the risk of having depression.

Sex Differential

A post hoc analysis confirmed the association of hypothyroidism and depression in female individuals (OR, 1.5) but not in male individuals (OR, 0.7). This possible gradient may be caused by physiological differences. In a randomized clinical trial, supraphysiological add-on thyroxine in patients with depression and bipolar disorder was effective in female but not in male individuals.53 On the other hand, female individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism did not benefit regarding depressive symptoms when they had been given antenatal thyroxine compared with placebo.54 In any case, this finding may be false positive because results were reported by sex in only 4 studies and sex has been included in adjustments in several studies.

Limitations

The inclusion of a multitude of studies led to variations in study design and methods of assessment. For example, the study by Benseñor et al22 was conducted with civil servants. However, we consider it unlikely that such a selection introduces bias. We did not investigate absolute risks, and a differential bias seems unlikely in the studies included. Nevertheless, in a sensitivity analysis, we restricted our summary estimate to studies that are strictly population based, and results did not substantially change (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Another limitation arises from varying recruitment processes of studies. Most samples consisted of random samples or complete registers of the population, and others, like Bould et al,23 recruited participants from a primary or ambulatory care setting, possibly introducing biases. Reassuringly, leaving out such studies showed no substantially different results.

Several investigations included patients taking thyroid medication, which may have blurred an association of underlying hypothyroidism with depression. However, when we contrasted studies with vs those without intake of thyroid medication, we found a stronger association with medication (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Therefore, in these studies, thyroid medication may be an indicator of severe thyroid disorder rather than a successful treatment of depression.

Further, several studies used cutoff values for cases, but in a strict sense, cutoffs represent a range of symptoms rather than diagnostic entities. However, they serve their purpose as reasonably good approximations in large epidemiologic studies, as discussed, for example, in the article by Engum et al28 from Norway. Nevertheless, we have carried out a sensitivity analysis restricted to those studies and found only marginal differences from the main analysis (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Between-study heterogeneity, as measured by I2, was substantial in various analyses. Single studies24,27,43,44 exerted a strong influence on I2, but their elimination from the analysis did not significantly change the main results. It is important to bear in mind that with large sample sizes, as in our study with a combined N close to 350 000 individuals, I2 is expected to be large. An indicator of heterogeneity independent of sample size is tau,55 and the fact that tau is low supports the robustness of our findings (Table 2; eTable 2 in the Supplement). In sum, while the confidence intervals and even more so the prediction intervals show that larger or smaller effects remain a possibility, the present evidence suggests a moderate association of hypothyroidism and clinical depression.

We cannot draw conclusions regarding hypothyroidism in pregnancy because in our sample of studies, pregnant individuals were often excluded based on the assumption that hypothyroidism in pregnancy differs from that seen in the general population. Recently, however, Minaldi et al56 published a meta-analysis specifically on pregnancy and the postpartum period and found an association similar to our result. In the 5 studies summarized, the risk ratio of developing postpartum depression among individuals who were positive for TPO antibodies compared with those unaffected was 1.49 (95% CI, 1.11-2.0). Assuming a causal relationship, by the numbers of this study, 1 in 21 female individuals with TPO antibodies will experience postpartum depression because of their thyroid condition. Against the backdrop of the generally assumed 10% to 15% prevalence of postpartum depression,57 the finding does support current clinical practice because in individuals who recently gave birth, health care personnel need to be aware of incident depression.

Because it was necessary to calculate associations for many of the included samples, effect sizes differ in degrees of adjustment. We tried to compensate for this by including minimally adjusted effect sizes. This, in turn, may have led to an overestimation of associations.

Conclusions

It may be time to reconsider the paradigm of a strong connection between hypothyroidism and depression. The results of other groups and our own findings indicate the contribution of hypothyroidism to the pandemic of depression is probably small. This is good news for patients with hypothyroidism or, in particular, with thyroid autoimmunity. In counseling, we may not be able to rule out depression as a comorbidity, but it is not looming large as a very likely threat. Regarding research, it appears autoimmunity is not a forceful driver of affective symptoms. A more promising link seems to be the level of thyroid hormones and disturbances of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal/hypothalamic pituitary thyroid axis. Finally, our results point to a possible effect of sex on the interaction of hypothyroidism and depression.

eMethods.

eTable 1. Included Studies

eTable 2. Additional Results

eReferences.

References

- 1.Joffe RT, Sokolov ST. Thyroid hormones, the brain, and affective disorders. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1994;8(1-2):45-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer M, Goetz T, Glenn T, Whybrow PC. The thyroid-brain interaction in thyroid disorders and mood disorders. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20(10):1101-1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hage MP, Azar ST. The link between thyroid function and depression. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:590648. doi: 10.1155/2012/590648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jucevičiūtė N, Žilaitienė B, Aniulienė R, Vanagienė V. The link between thyroid autoimmunity, depression and bipolar disorder. Open Med (Wars). 2019;14:52-58. doi: 10.1515/med-2019-0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(1):24-31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegmann EM, Müller HHO, Luecke C, Philipsen A, Kornhuber J, Grömer TW. Association of depression and anxiety disorders with autoimmune thyroiditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):577-584. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegmann EM, Grömer TW. Additional data from omitted study in a meta-analysis of the association of depression and anxiety with autoimmune thyroiditis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(8):871. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baethge C. Autoimmune thyroiditis and depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(11):1204-1204. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hennessey JV. Autoimmune thyroiditis and depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(11):1204-1205. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wildisen L, Del Giovane C, Moutzouri E, et al. An individual participant data analysis of prospective cohort studies on the association between subclinical thyroid dysfunction and depressive symptoms. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19111. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75776-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(n71):n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smarr KL, Keefer AL. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(suppl 11):S454-S466. doi: 10.1002/acr.20556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. The Ottawa Hospital. Accessed April 28, 2021. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 14.Modesti PA, Reboldi G, Cappuccio FP, et al. ; ESH Working Group on CV Risk in Low Resource Settings . Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342:d549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455-463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health. 2019;22(4):153-160. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Software. 2010;36(3):48. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almeida OP, Alfonso H, Flicker L, Hankey G, Chubb SA, Yeap BB. Thyroid hormones and depression: the Health in Men study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(9):763-770. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820dcad5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benseñor IM, Nunes MA, Sander Diniz MF, Santos IS, Brunoni AR, Lotufo PA. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and psychiatric disorders: cross-sectional results from the Brazilian Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;84(2):250-256. doi: 10.1111/cen.12719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bould H, Panicker V, Kessler D, et al. Investigation of thyroid dysfunction is more likely in patients with high psychological morbidity. Fam Pract. 2012;29(2):163-167. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carta MG, Loviselli A, Hardoy MC, et al. The link between thyroid autoimmunity (antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies) with anxiety and mood disorders in the community: a field of interest for public health in the future. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Jongh RT, Lips P, van Schoor NM, et al. Endogenous subclinical thyroid disorders, physical and cognitive function, depression, and mortality in older individuals. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165(4):545-554. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delitala AP, Terracciano A, Fiorillo E, Orrù V, Schlessinger D, Cucca F. Depressive symptoms, thyroid hormone and autoimmunity in a population-based cohort from Sardinia. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:82-87. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engum A, Bjøro T, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. An association between depression, anxiety and thyroid function: a clinical fact or an artefact? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(1):27-34. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engum A, Bjøro T, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Thyroid autoimmunity, depression and anxiety; are there any connections? an epidemiological study of a large population. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(5):263-268. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fjaellegaard K, Kvetny J, Allerup PN, Bech P, Ellervik C. Well-being and depression in individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity: a general population study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(1):73-78. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.929741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guimarães JM, de Souza Lopes C, Baima J, Sichieri R. Depression symptoms and hypothyroidism in a population-based study of middle-aged Brazilian women. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(1-2):120-123. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong JW, Noh JH, Kim DJ. Association between subclinical thyroid dysfunction and depressive symptoms in the Korean adult population: the 2014 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ittermann T, Völzke H, Baumeister SE, Appel K, Grabe HJ. Diagnosed thyroid disorders are associated with depression and anxiety. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(9):1417-1425. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1043-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SY, et al. Thyroid stimulating hormone, cognitive impairment and depression in an older Korean population. Psychiatry Investig. 2010;7(4):264-269. doi: 10.4306/pi.2010.7.4.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JS, Zhang Y, Chang Y, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and incident depression in young and middle-age adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(5):1827-1833. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kvetny J, Ellervik C, Bech P. Is suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) associated with subclinical depression in the Danish General Suburban Population Study? Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(4):282-286. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.972454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S, Oh SS, Park EC, Jang SI. Sex differences in the association between thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and depressive symptoms among the general population with normal free T4 levels. J Affect Disord. 2019;249:151-158. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin IC, Chen HH, Yeh SY, Lin CL, Kao CH. Risk of depression, chronic morbidities, and l-thyroxine treatment in Hashimoto thyroiditis in Taiwan: a nationwide cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(6):e2842. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manciet G, Dartigues JF, Decamps A, et al. The PAQUID survey and correlates of subclinical hypothyroidism in elderly community residents in the southwest of France. Age Ageing. 1995;24(3):235-241. doi: 10.1093/ageing/24.3.235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maugeri D, Motta M, Salerno G, et al. Cognitive and affective disorders in hyper- and hypothyreotic elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1998;26:305-312. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4943(98)80043-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medici M, Direk N, Visser WE, et al. Thyroid function within the normal range and the risk of depression: a population-based cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(4):1213-1219. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park YJ, Lee EJ, Lee YJ, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) is not associated with metabolic derangement, cognitive impairment, depression or poor quality of life (QoL) in elderly subjects. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(3):e68-e73. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pop VJ, Maartens LH, Leusink G, et al. Are autoimmune thyroid dysfunction and depression related? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(9):3194-3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shinkov AD, Borisova AM, Kovacheva RD, et al. Influence of serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies, age and gender on depression as measured by the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2014;56(1):24-31. doi: 10.2478/folmed-2014-0004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomsen AF, Kvist TK, Andersen PK, Kessing LV. Increased risk of developing affective disorder in patients with hypothyroidism: a register-based study. Thyroid. 2005;15(7):700-707. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van de Ven AC, Muntjewerff JW, Netea-Maier RT, et al. Association between thyroid function, thyroid autoimmunity, and state and trait factors of depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(5):377-384. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01870.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loh HH, Lim LL, Yee A, Loh HS. Association between subclinical hypothyroidism and depression: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-2006-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao T, Chen BM, Zhao XM, Shan ZY. Subclinical hypothyroidism and depression: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):239. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0283-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. ; National Comorbidity Survey Replication . The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095-3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patten SB, Williams JV, Esposito E, Beck CA. Self-reported thyroid disease and mental disorder prevalence in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(6):503-508. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patten SB, Williams JVA, Lavorato DH, et al. Patterns of association of chronic medical conditions and major depression. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(1):42-50. doi: 10.1017/S204579601600072X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stamm TJ, Lewitzka U, Sauer C, et al. Supraphysiologic doses of levothyroxine as adjunctive therapy in bipolar depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(2):162-168. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Costantine MM, Smith K, Thom EA, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network, Bethesda, MD . Effect of thyroxine therapy on depressive symptoms among women with subclinical hypothyroidism. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(4):812-820. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I(2) in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Minaldi E, D’Andrea S, Castellini C, et al. Thyroid autoimmunity and risk of post-partum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020;43(3):271-277. doi: 10.1007/s40618-019-01120-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anokye R, Acheampong E, Budu-Ainooson A, Obeng EI, Akwasi AG. Prevalence of postpartum depression and interventions utilized for its management. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2018;17:18. doi: 10.1186/s12991-018-0188-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eTable 1. Included Studies

eTable 2. Additional Results

eReferences.