Abstract

Heparan sulfate (HS) can play important roles in the biology and pathology of amyloid β (Aβ), a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. To better understand the structure–activity relationship of HS/Aβ interactions, synthetic HS oligosaccharides ranging from tetrasaccharides to decasaccharides have been utilized to study Aβ interactions. Surface plasmon resonance experiments showed that the highly sulfated HS tetrasaccharides bearing full 2-O, 6-O, and N-sulfations exhibited the strongest binding with Aβ among the tetrasaccharides investigated. Elongating the glycan length to hexa- and deca-saccharides significantly enhanced Aβ affinity compared to the corresponding HS tetrasaccharide. Solid state NMR studies of the complexes of Aβ with HS hexa- and deca-saccharides showed most significant chemical shift perturbation in the C-terminus residues of Aβ. The strong binding HS oligosaccharides could reduce the cellular toxicities induced by Aβ. This study provides new insights into HS/Aβ interactions, highlighting how synthetic structurally well-defined HS oligosaccharides can assist in biological understanding of Aβ.

Graphical Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the most common form of dementia, which has been estimated to afflict millions of people in the U.S. alone.1 A prominent pathological hallmark of AD is amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques, where Aβ polypeptides aggregate with nonprotein components including carbohydrates to form plaques.2 Cell surface carbohydrates such as heparan sulfate (HS) can play important roles in Aβ biology.3,4 HS is a class of highly sulfated glycans, consisting of disaccharide repeating units of glucosamine-α–1,4-iduronic acid/glucuronic acid.5 The N, 3-O, and 6-O of the glucosamine, and the 2-O position of the uronic acid can be sulfated, rendering HS a class of biomacromolecules with the highest density of negative charges in nature. HS can be displayed on the surface of neuronal cells as part of the heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), which are known to be expressed at significantly higher levels in transgenic animal models of AD as well as in post-mortem human brain tissues from AD patients.3,4,6 Through binding of Aβ, cell surface HS can lead to the accumulation and the deposition of cytotoxic Aβ on neuronal cells. Furthermore, HSPGs can mediate Aβ internalization into the neuronal cells exacerbating neurotoxicity.7,8

HS and heparin (HS with higher levels of sulfations and iduronic acid) can have potential beneficial effects on AD patients.9 In clinical studies, administration of heparin like compounds has been shown to relieve behavioral symptoms in animal models of Alzheimer disease as well as in multi-infarct dementia human patients, although these compounds cannot be used directly for AD treatment due to concerns of potential bleeding side effects associated with anticoagulant activities of native heparin.10–12 HS mimics or nanoparticles can help mitigate cytotoxic Aβ species,13,14 providing exciting leads for AD detection and therapy.

With the appreciation of the roles of HS in Aβ biology, it is important to gain a deeper understanding of how the structural parameters of HS affect Aβ interactions. Utilizing oligosaccharides isolated through degradation of heparin polysaccharides, Hung and co-workers showed that the HS tetrasaccharides can bind with Aβ with a dissociation constant of 78 μM as determined by NMR.15 No significant differences between the Kd values (Kd ~ 40 μM) from hexamer to octadecamer were observed. In addition, the Radford and Middleton groups probed the importance of HS sulfation patterns.16 Utilizing HS polysaccharides chemically treated to selectively remove sulfates, they reported that the N-sulfate or 6-O-sulfate of glucosamine, but not the 2-O-sulfate of iduronate, was required for Aβ binding, indicating that selectivity in the interactions of HS with Aβ fibrils extends beyond general electrostatic complementarity. Other studies utilized fragments rather than full length Aβ peptides to probe HS/Aβ interactions.17 While the aforementioned studies have provided exciting insights into HS/Aβ interactions, a potential drawback in relying on HS isolated from nature is that chemical modification and degradation of heparin polysaccharides are not site specific. In addition, with the inherent structure heterogeneity of the polysaccharide,18 the compounds subject to Aβ binding were presumably still a mixture. Thus, we become interested in probing structural requirements for Aβ binding using well-defined synthetic HS oligosaccharides, which include HS tetrasaccharides 1–4 with varying sulfation patterns, HS hexasaccharide 5,19 and decasaccharide 6.20

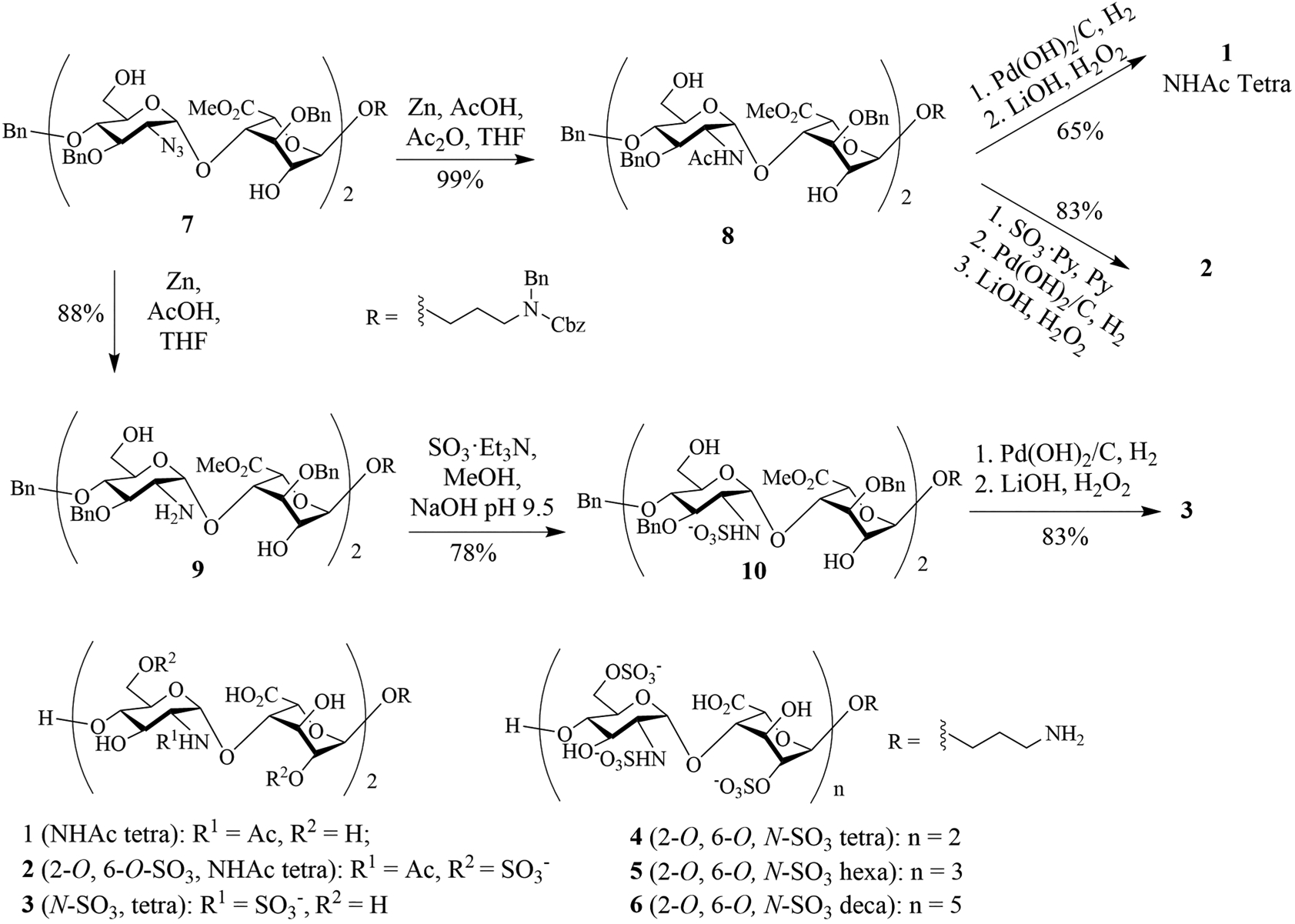

The synthesis of HS tetrasaccharides 1–3 started from tetrasaccharide 7.20 The 2-azido groups of tetrasaccharide 7 were reduced by zinc and acetic acid in the presence of acetic anhydride to provide 8 with two N-acetamides in 99% yield (Scheme 1), which was hydrogenated followed by saponification, generating tetrasaccharide 1 in 65% yield for the two steps. Alternatively, the free hydroxyl groups of 8 were sulfated with SO3·pyridine in pyridine at 55 °C followed by global deprotection leading to tetrasaccharide 2 (83% overall yield for 3 steps). In order to prepare the N-sulfated tetrasaccharide 3, 7 was reduced with zinc and acetic acid without the addition of acetic anhydride in 88% yield. Sulfation of the two free amines in the resulting tetrasaccharide 9 was performed by first dissolving it in methanol with aqueous NaOH solution adjusting the pH to 10, which was followed by the addition of excess SO3·Et3N complex to yield N-sulfated tetrasaccharide 10. Global deprotection of 10 produced the tetrasaccharide 3. Compounds 4–6 were prepared as previously described.19,20

Scheme 1.

Structures of HS Oligosaccharides 1–6 and Synthesis of HS Tetrasaccharides 1–3

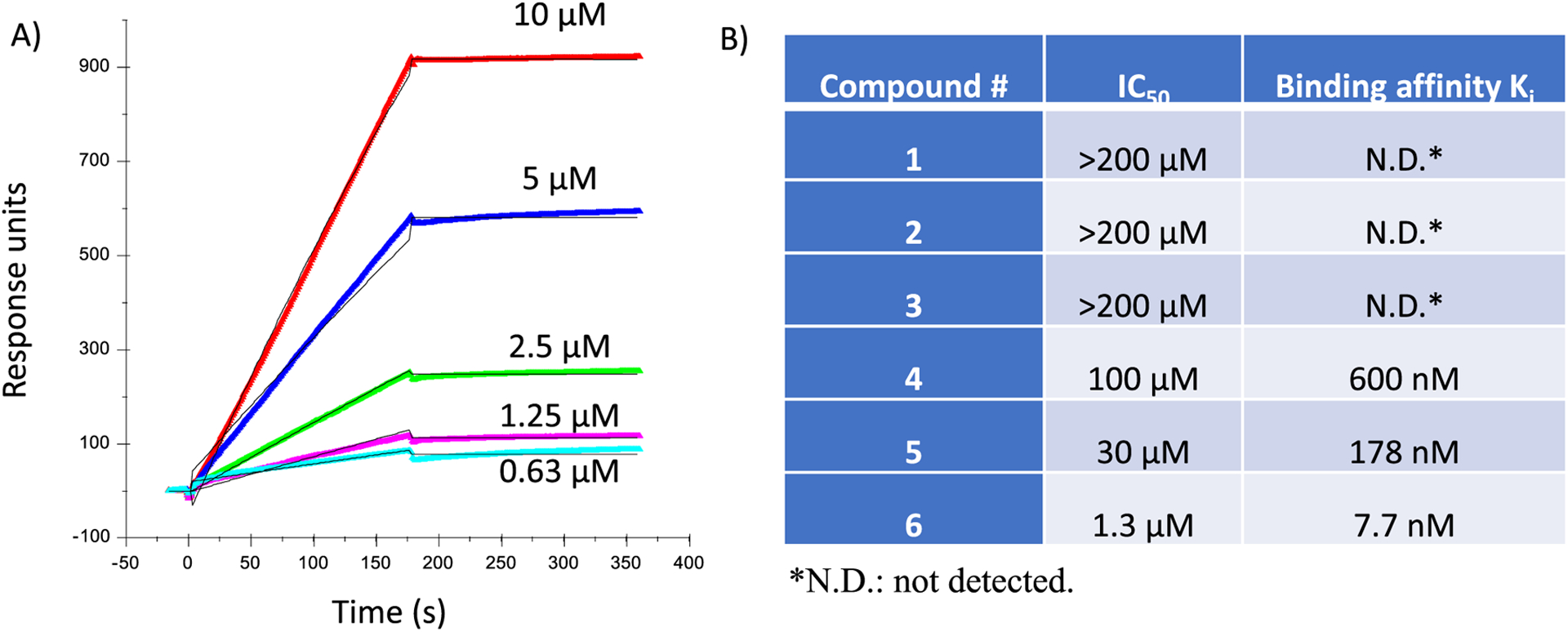

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assays were set up to measure HS-Aβ binding to decipher structural impacts of HS on Aβ interactions using a solution affinity assay.21 Biotinylated heparin polysaccharide was immobilized onto a streptavidin sensor chip, which was incubated with solutions of Aβ with varying concentrations. From the resulting sensorgrams (Figure 1A), a Kd value of 15 nM for heparin-Aβ binding was calculated. Solution/surface competition experiments were performed by incubating increasing concentrations of HS oligosaccharides with Aβ before adding the mixture to the heparin sensor chip to measure the affinity of the synthetic HS oligosaccharides. The binding of the oligosaccharide with Aβ would competitively inhibit the interaction of Aβ with the heparin chip, thus reducing the responses observed on the SPR sensor. From these experiments, the IC50 values of the oligosaccharides were obtained (Figure 1B). Kd values were calculated from the SPR association and dissociation curves using Biacore BIAevaluation software. In a comparison of the tetrasaccharides 1–4, only tetrasaccharide 420 bearing three sulfates per disaccharide exhibited significant binding. As 4 has the highest density of negative charges, it suggests the importance of electrostatic interactions for HS tetrasaccharide-Aβ binding. Increasing the length of the oligosaccharides from tetra- (4) to hexa- (5) and deca- (6) saccharide led to significant increases in affinity with a Ki value of 7.7 nM determined for decasaccharide 6. It suggests that with the same number of negative charges per disaccharide, longer HS oligosaccharides have stronger binding with Aβ. This is in contrast to the trend observed using oligosaccharides obtained from the degradation of a naturally existing polysaccharide, where there were no significant changes in Kd values from hexamer to octadecamer.15 The difference may be due to the fact that naturally derived compounds are a mixture of glycans with various sulfation patterns, masking the effects caused by the changes in glycan length.

Figure 1.

(A) SPR sensorgrams of Aβ40 binding with a heparin chip. Solutions of Aβ (0.63, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM) were flowed over the heparin chip. On the basis of the responses, a Kd value of 15 nM for heparin-Aβ binding was calculated. (B) IC50 values and inhibitory constants of various synthetic HS oligosaccharides binding with Aβ as determined by a solution/surface competition experiments against Aβ binding to heparin immobilized on an SPR sensor. IC50 was calculated based on the protein binding signals from the sensorgrams with the addition of HS oligosaccharides in different concentrations. Solution based affinities (Ki) were calculated from IC50 measured from SPR competition experiments using the equation: Ki = IC50/(1 + [C]/KD); [C] = protein concentration used in the competition SPR; KD is protein-heparin binding affinity.

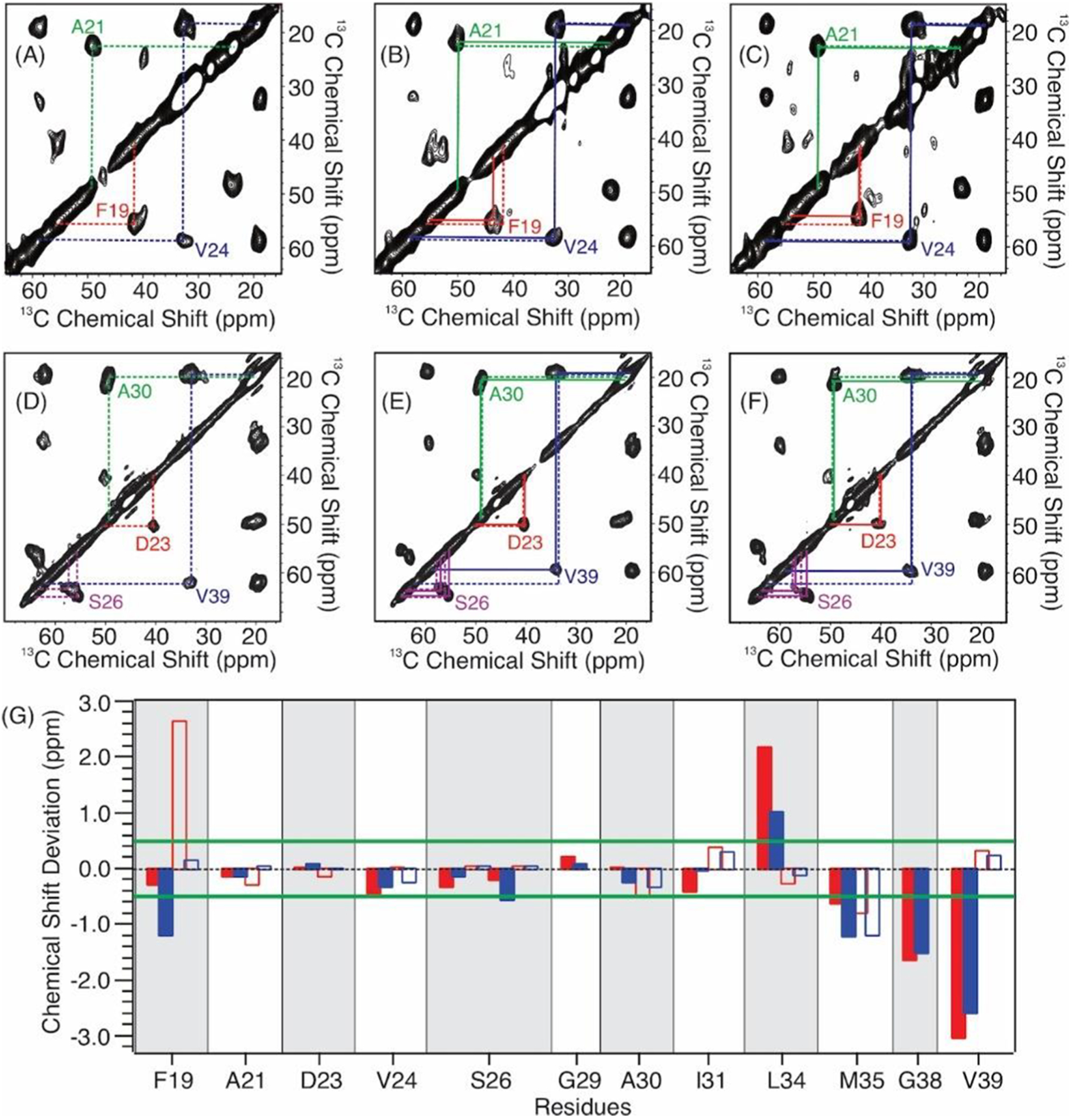

To obtain more structural insights into HS-Aβ binding, we utilized the solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) spectroscopy to investigate the residue-specific 13C chemical shift perturbations of Aβ fibrils upon interacting with HS hexasaccharide 5 and decasaccharide 6 respectively. Three isotopically labeled Aβ sequences were synthesized with labeling sites (F19, A21, D23, V24, S26, G29, A30, I31, L34, M35, G38, and V39) that covered the typical fibrillar core segments of Aβ40 fibrils.22–25 All fibril samples were prepared using the quiescent incubation protocols (i.e., resulting fibrils with a 3-fold symmetric quaternary structure, or 3Q fibrils).26

The representative two-dimensional (2D) 13C–13C spin diffusion ssNMR spectra (Figure 2A–F) highlighted the intramolecular cross-peaks of selective residues. Single sets of cross peaks were observed for most of the labeled sites, indicating well-defined local conformations in 3Q Aβ fibrils with and without HS oligosaccharides. A few residues, such as S26, possessed local structural heterogeneity with multiple sets of cross peaks. Upon incubation with HS oligosaccharides, 13C chemical shift perturbations were observed at specific residues (Table S1) with the hexasaccharide 5 and decasaccharide 6 giving comparable patterns of chemical shift changes suggesting similar binding modes for these two oligosaccharides (Figure 2G). Overall, the perturbations were most significant for residues F19, L34, M35, G38, and V39 and modest for S26, A30, and I31, while little changes were observed for A21, D23, V24, and G29.

Figure 2.

(A–F) Representative 2D 13C–13C spin diffusion ssNMR spectra of (A, D) free 3Q Aβ40 fibrils, (B, E) Aβ fibrils with HS hexamer 5, and (C, F) Aβ fibrils with HS decamer 6. The Aβ sequences contain isotope-labeling at (A–C) F19, A21, V24, and G29 and (D–F) D23, S26, A30, and V39. The dashed lines in panels A and D highlight the intraresidue cross peaks in the free fibrils. The solid lines in panels B, C, E, and F show the intraresidue cross peaks in the HS-bound fibrils to emphasize the deviations in chemical shifts from the free fibrils (dashed lines in the same panel). (G) Plots of the residue-specific 13C chemical shift deviations (i.e., Δδ = δheparin-bound fibrils − δfree fibrils) in the presence of HS hexasaccharide 5 (solid red columns, Cα; open red columns, Cβ) and decasaccharide 6 (solid blue columns, Cα; open blue columns, Cβ). The green lines highlight the 0.5 ppm threshold for significant chemical shift deviations based on the 13C line widths in ssNMR spectra.

The current ssNMR study provides new insights into the site-specific interactions between HS and Aβ fibrils. Middleton and co-workers reported the site-specific interactions between an HS octasaccharide and the 3Q Aβ fibrils by ssNMR, where large 13C chemical shift perturbations were also observed for residues S26, A30, I31, and L34 with minimal perturbations for A21 and D23.16 On the other hand, the significant 13C chemical shift perturbations at L34, M35, G38, and V39 observed in our study suggest an additional fibrillar segment that may bind to the HS oligomers. In the molecular structure of 3Q Aβ fibrils, these residues are in close proximity with the segment A30–I32 of a neighboring Aβ molecule,26 where the latter residues showed significant chemical shift perturbations in the previous report.16 This cluster of residues located in the pore region of 3Q Aβ fibrils is accessible to water molecules, where water can bind to this pore region and the polar interfaces consisting of terminal and interstrand loop residues possess similar spectroscopic and dynamic properties.27 Thus, it is reasonable that the water-soluble HS oligosaccharides may enter and bind to the fibrillar pore. For residue S26, while multiple intraresidue cross peaks were observed in free 3Q Aβ fibrils (Figure 2D), these cross peaks became more defined (e.g., two sets of peaks, Figure 2E) upon binding to the hexamer 5, and one set of cross peaks became predominant in the presence of HS decamer 6 (Figure 2F). The local conformation of S26 was less ordered compared to the β-sheet segments (e.g., L17–A21 and A30–V36) in the unbound 3Q Aβ fibrils.26 It is possible that the binding between HS oligomers and the fibrils rigidifies the complex structure, thus reducing the number of local conformers at the S26 site with the tighter binding decamer 6 leading to one major conformation.

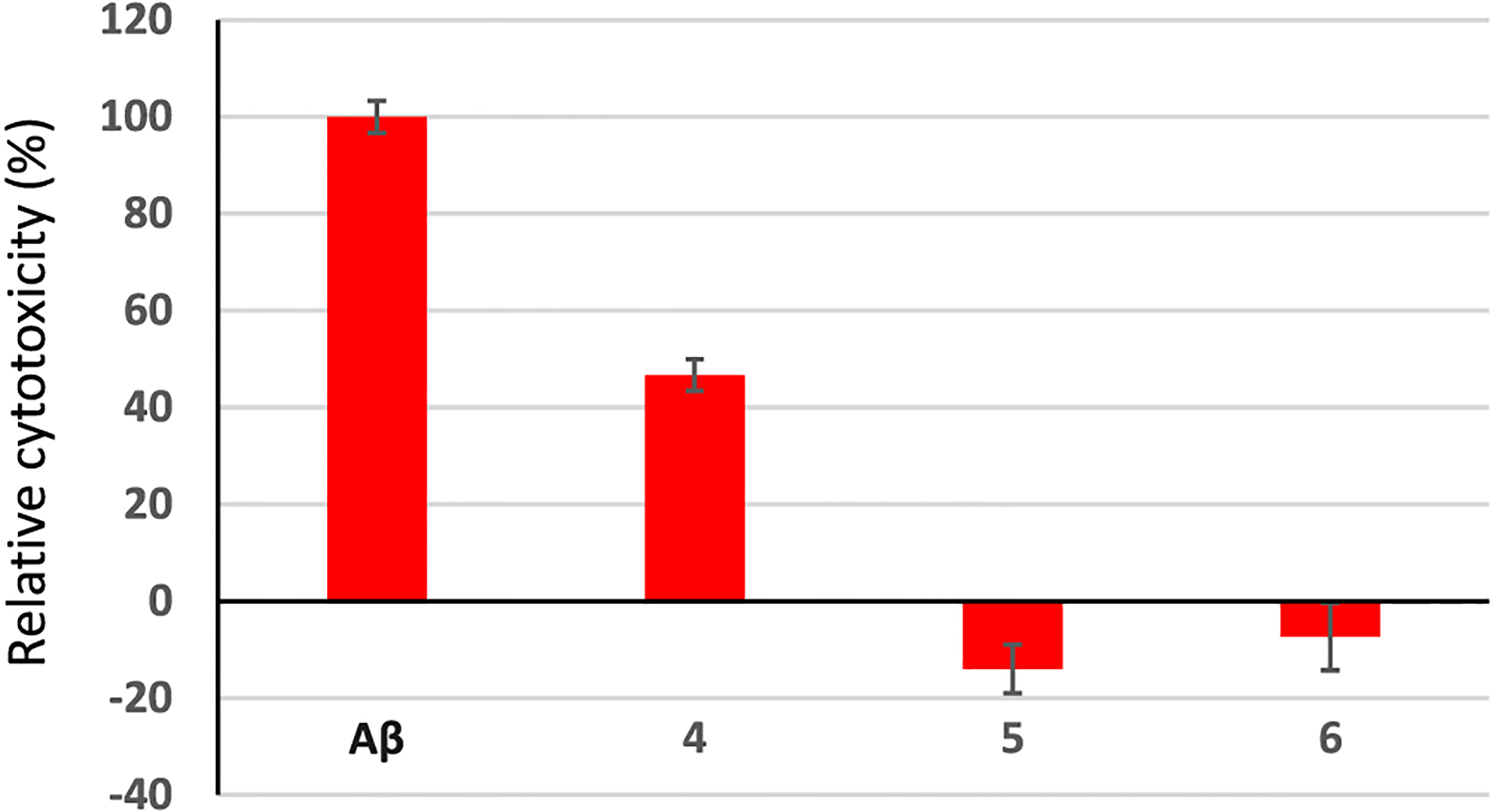

Aβ is known to be toxic to neuronal cells,28 which can be a contributing factor to Aβ pathology in vivo. As the synthetic HS oligosaccharides can bind with Aβ, their impacts on Aβ toxicities were tested with the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line, a common model for neuronal screening.29 SH-SY5Y cells were incubated with Aβ in the presence of various HS oligosaccharides, and the viabilities of the cells were determined. As shown in Figure 3, HS oligosaccharides reduced Aβ toxicities with the hexasaccharide 5 and decasaccharide 6 providing complete protection under the experimental conditions. The abilities of the HS oligosaccharides to mitigate Aβ toxicity could be because HS binding shielded the toxic Aβ from interacting with HS on the cell surface.

Figure 3.

HS oligosaccharides can reduce the cytotoxicity of Aβ to SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells (2 × 104) were incubated with or without Aβ (30 μM) for 48 h. The numbers of viable cells were determined via the MTS cell viability assay. The change of the cell number due to Aβ was determined. Cells were then incubated with Aβ (30 μM) in the presence of HS 4, 5, and 6 (60 μM), respectively. The numbers of viable cells were determined by the MTS cell viability assay after 48 h, respectively. The changes in cell numbers were calculated compared to cells cultured in media only. Relative cytotoxicity values were calculated based on the following formula: (changes of the number of cells with HS/Aβ)/(changes of the number of cells with Aβ only) × 100%.

In conclusion, HS tetrasaccharides with varying sulfation patterns have been synthesized. The binding of these tetrasaccharides as well as synthetic HS hexa- and deca-saccharides with Aβ have been measured by SPR. The highly sulfated tetrasaccharide 4 exhibited the strongest binding with Aβ among the tetrasaccharides tested. Increasing the length of the glycan from tetrasaccharide to decasaccharide significantly enhanced the affinity with Aβ. ssNMR studies demonstrated that HS binding could induce significant chemical shift perturbations in Aβ fibrils, with major changes observed within the C-terminus residues. The HS oligosaccharides could reduce the cellular toxicities induced by Aβ. As these synthetic HS oligosaccharides lack the 3-O sulfation, they should not have any anticoagulation activities. Thus, HS oligosaccharides can be leads for the further development of HS glycan-based mimetics to treat Alzheimer disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the financial support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIH (R01GM072667).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschembio.0c00904.

Detailed experimental procedures, preparation, and characterization of the products (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acschembio.0c00904

Contributor Information

Peng Wang, Department of Chemistry and Institute for Quantitative Health Science and Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, United States.

Jing Zhao, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York 12180, United States.

Seyedmehdi Hossaini Nasr, Department of Chemistry and Institute for Quantitative Health Science and Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, United States.

Sarah A. Otieno, Department of Chemistry, Binghamton University, State University of New York, Binghamton, New York 13902, United States

Fuming Zhang, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York 12180, United States;.

Wei Qiang, Department of Chemistry, Binghamton University, State University of New York, Binghamton, New York 13902, United States;.

Robert J. Linhardt, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York 12180, United States;.

Xuefei Huang, Department of Chemistry, Institute for Quantitative Health Science and Engineering, and Department of Biomedical Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, United States;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Alzheimer’s Association (2020) 2020 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia 16, 391–460. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Stewart KK, and Radford SE (2017) Amyloid plaques beyond Aβ: a survey of the diverse modulators of amyloid aggregation. Biophys. Rev 9, 405–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Liu C-C, Zhao N, Yamaguchi Y, Cirrito JR, Kanekiyo T, Holtzman DM, and Bu G (2016) Neuronal heparan sulfates promote amyloid pathology by modulating brain amyloid-β clearance and aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med 8, 332ra44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhang G. l., Zhang X, Wang X-M, and Li J-P (2014) Towards Understanding the Roles of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans in Alzheimer’s Disease. BioMed Res. Int 2014, 516028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Linhardt RJ (2003) 2003 Claude S. Hudson Award Address in Carbohydrate Chemistry. Heparin: Structure and Activity. J. Med. Chem 46, 2551–2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).O’Callaghan P, Sandwall E, Li J-P, Yu H, Ravid R, Guan Z-Z, Van Kuppevelt TH, Nilsson LNG, Ingelsson M, Hyman BT, Kalimo H, Lindahl U, Lannfelt L, and Zhang X (2008) Heparan Sulfate Accumulation with Aβ Deposits in Alzheimer’s Disease and Tg2576 Mice is Contributed by Glial Cells. Brain Pathol. 18, 548–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sandwall E, O’Callaghan P, Zhang X, Lindahl U, Lannfelt L, and Li J-P (2010) Heparan sulfate mediates amyloid-beta internalization and cytotoxicity. Glycobiology 20, 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Letoha T, Hudák A, Kusz E, Pettkó-Szandtner A, Domonkos I, Jósvay K, Hofmann-Apitius M, and Szilák L (2019) Contribution of syndecans to cellular internalization and fibrillation of amyloid-β(1–42). Sci. Rep 9, 1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bergamaschini L, Rossi E, Vergani C, and De Simoni MG (2009) Alzheimer’s Disease: Another Target for Heparin Therapy. Sci. World J 9, 891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Santini V (1989) A general practice trial of Ateroid 200 in 8,776 patients with chronic senile cerebral insufficiency. Mod. Trends Pharmacopsychiatry 23, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Passeri M, and Cucinotta D (1989) Ateroid in the clinical treatment of multi-infarct dementia. Mod. Trends Pharmacopsychiatry 23, 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ma Q, Cornelli U, Hanin I, Jeske WP, Linhardt RJ, Walenga JM, Fareed J, and Lee JM (2007) Heparin Oligosaccharides as Potential Therapeutic Agents in Senile Dementia. Curr. Pharm. Des 13, 1607–1616 and references cited therein.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hawkes CA, Ng V, and McLaurin J (2009) Small molecule inhibitors of Aβ-aggregation and neurotoxicity. Drug Dev. Res 70, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wang P, Kouyoumdjian H, Zhu DC, and Huang X (2015) Heparin nanoparticles for β amyloid binding and mitigation of β amyloid associated cytotoxicity. Carbohydr. Res 405, 110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Stewart KL, Hughes E, Yates EA, Akien GR, Huang T-Y, Lima MA, Rudd TR, Guerrini M, Hung S-C, Radford SE, and Middleton DA (2016) Atomic Details of the Interactions of Glycosaminoglycans with Amyloid-β Fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 8328–8331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Madine J, Pandya MJ, Hicks MR, Rodger A, Yates EA, Radford SE, and Middleton DA (2012) Site-Specific Identification of an Ab Fibril–Heparin Interaction Site by Using Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 51, 13140–13143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Nguyen K, and Rabenstein DL (2016) Interaction of the Heparin-Binding Consensus Sequence of β-Amyloid Peptides with Heparin and Heparin-Derived Oligosaccharides. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 2187–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zhang F, Yang B, Ly M, Solakyildirim K, Xiao Z, Wang Z, Beaudet JM, Torelli AY, Dordick JS, and Linhardt RJ (2011) Structural characterization of heparins from different commercial sources. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 401, 2793–2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Dulaney SB, Xu Y, Wang P, Tiruchinapally G, Wang Z, Kathawa J, El-Dakdouki MH, Yang B, Liu J, and Huang X (2015) Divergent synthesis of heparan sulfate oligosaccharides. J. Org. Chem 80, 12265–12279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wang P, Lo Cascio F, Gao J, Kayed R, and Huang X (2018) Binding and neurotoxicity mitigation of toxic Tau oligomers by synthetic heparin like oligosaccharides. Chem. Commun 54, 10120–10123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Cochran S, Li CP, and Ferro V (2009) A surface plasmon resonance-based solution affinity assay for heparan sulfate-binding proteins. Glycoconjugate J. 26, 577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tycko R (2015) Amyloid polymorphism: structural basis and neurobiological relevance. Neuron 86, 632–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Sgourakis NG, Yau W-M, and Qiang W (2015) Modeling an in-register, parallel ‘iowa’ Aβ fibril structure using solid-state NMR data from labeled samples with Rosetta. Structure 23, 216–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hu Z-W, Vugmeyster L, Au DF, Ostrovsky D, Sun Y, and Qiang W (2019) Molecular structure of an N-terminal phosphorylated β-amyloid fibril. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116, 11253–11258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ghosh U, Thurber KR, Yau W-M, and Tycko R (2021) Molecular structure of a prevalent amyloid-β fibril polymorph from Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 118, e2023089118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Paravastu AK, Leapman RD, Yau W-M, and Tycko R (2008) Molecular structural basis for polymorphism in Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 18349–18354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Wang T, Jo H, DeGrado WF, and Hong M (2017) Water Distribution, Dynamics, and Interactions with Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid Fibrils Investigated by Solid-State NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 6242–6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Carrillo-Mora P, Luna R, and Colín-Barenque L (2014) Amyloid Beta: Multiple Mechanisms of Toxicity and Only Some Protective Effects? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2014, 795375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Krishtal J, Bragina O, Metsla K, Palumaa P, and Tõugu V (2017) In situ fibrillizing amyloid-beta 1–42 induces neurite degeneration and apoptosis of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. PLoS One 12, e0186636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.