Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate thermodynamic and kinetic properties on the hydrogen-atom-donating ability of 4-substituted Hantzsch ester radical cations (XRH•+), which are excellent NADH coenzyme models. Gibbs free energy changes and activation free energies of 17 XRH•+ releasing H• [denoted as ΔGHDo(XRH•+) and ΔGHD(XRH•+)] were calculated using density functional theory (DFT) and compared with that of Hantzsch ester (HEH2) and NADH. ΔGHDo(XRH•+) range from 19.35 to 31.25 kcal/mol, significantly lower than that of common antioxidants (such as ascorbic acid, BHT, the NADH coenzyme, and so forth). ΔGHD(XRH•+) range from 29.81 to 39.00 kcal/mol, indicating that XRH•+ spontaneously releasing H• are extremely slow unless catalysts or active intermediate radicals exist. According to the computed data, it can be inferred that the Gibbs free energies and activation free energies of the core 1,4-dihydropyridine radical cation structure (DPH•+) releasing H• [ΔGHDo(DPH•+) and ΔGHD(DPH•+)] should be 19–32 kcal/mol and 29–39 kcal/mol in acetonitrile, respectively. The correlations between the thermodynamic driving force [ΔGHDo(XRH•+)] and the activation free energy [ΔGHD(XRH•+)] are also explored. Gibbs free energy is the important and decisive parameter, and ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) increases in company with the increase of ΔGHD(XRH•+), but no simple linear correlations are found. Even though all XRH•+ are judged as excellent antioxidants from the thermodynamic view, the computed data indicate that whether XRH•+ is an excellent antioxidant in reaction is decided by the R substituents in 4-position. XRH•+ with nonaromatic substituents tend to release R• instead of H• to quench radicals. XRH•+ with aromatic substituents tend to release H• and be used as antioxidants, but not all aromatic substituted Hantzsch esters are excellent antioxidants.

Introduction

4-Substituted Hantzsch esters (XRH, Scheme 1), known as dipine drugs, are used to treat hypertensive and cardiovascular diseases as calcium channel modulators,1,2 which also have the 1,4-dihydropyridine structure and used as excellent NADH coenzyme models.3−5 XRH were investigated as antioxidants to quench active radicals (R•, RO•, ROO•, RS• or RNH•, and so on) in vivo and vitro in many papers.6−9 In recent years, XRH have been examined as alkyl reagents to synthetize various bioactive molecules, and the key elementary step is XRH•+ releasing R• (XRH•+ → XH+ + R•).10−16 However, not all XRH•+ can release R•; for example, 4-phenyl-Hantzsch ester could not release Ph• itself.10 We wonder that could XRH•+ be used as H• donors served as radical scavengers just like NADH and NADH•+ (Scheme 2). How could we quantitatively measure the hydrogen-atom-donating ability of XRH•+? Since the key elementary step of XRH•+ used as an antioxidant is XRH•+ releasing H•, in this work, the characteristic physical parameters of XRH•+, Gibbs free energy change [ΔGHDo(XRH•+)] and activation free energy of XRH•+ releasing H• [ΔGHD(XRH•+)], are obtained to judge the ability of XRH•+ releasing H•. However, because XRH•+ is a kind of very active intermediate, ΔGHDo(XRH•+) and ΔGHD(XRH•+) on the process of XRH•+ releasing H• are quite difficult to determine experimentally in labs. In present work, 17 important and well-designed XRH (Scheme 3) with various substituents in the 4-position, such as allyl, benzoyl, benzyl, and so on, are selected to further investigate the hydrogen-atom-donating ability of XRH•+ using density functional theory (DFT). We believe that these data would be helpful in the understanding and application of XRH•+ as antioxidants or radical donors.

Scheme 1. Chemical Structures of XRH, HEH2 and NADH.

Scheme 2. Key Elementary Step of XRH•+ Releasing H•.

Scheme 3. Chemical Structures of 17 XRH Investigated in This Work.

Methods

For the elementary step on each XRH•+ releasing H•, we found out the reactant, transition state (denoted as TS), and product structure through geometrical optimization; vibrational analysis showed that the reactants and products had no imaginary frequencies, and each transition state had only one imaginary frequency. Intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) was calculated for each transition state, and electron spin density analysis was applied on the IRC products and verified that the cleavage products were hydrogen radicals and not protons. Then, thermodynamic correction values of enthalpy and Gibbs free energy were calculated at 298.15 K, which were added to the single-point energy to give the enthalpy and Gibbs free energy, respectively. The ΔGHDo(XRH•+), ΔGHD(XRH•+), enthalpy change [ΔHHDo(XRH•+)], and activation enthalpy change [ΔHHD(XRH•+)] were calculated as eqs 1–4, respectively.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

The computation level of the geometrical optimization, vibrational analysis, and IRC calculation was B3LYP/6-31G(d,p);17,18 DFT-D3 empirical dispersion corrections (BJ damping)19 were applied, and the SMD solvent model20 of acetonitrile was used. DFT calculations were accomplished in Gaussian 09,21 and electron spin density analysis was done in Multiwfn 3.7.22 The accuracy of the calculation method has been verified in our previous work,16 and the calculation deviation is less than 2.0 kcal/mol.

Results and Discussion

The DFT-computed results of ΔGo(XRH•+), ΔG≠(XRH•+), ΔHo(XRH•+), and ΔH≠(XRH•+) of 17 XRH•+ releasing H• are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Gibbs Free Energy Change [ΔGHDo(XRH•+)], Activation Free Energy [ΔGHD(XRH•+)], Enthalpy Change [ΔHHDo(XRH•+)], and Activation Enthalpy [ΔHHD(XRH•+)] of XRH•+ Releasing H• at 298.15 K in Acetonitrile (Unit: kcal/mol).

| XRH | ΔGHDo(XRH•+) | ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) | ΔHHDo(XRH•+) | ΔHHD≠(XRH•+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1RH | 22.13 | 32.70 | 30.22 | 33.15 |

| 2RH | 23.56 | 34.90 | 30.80 | 34.72 |

| 3RH | 26.03 | 34.13 | 33.56 | 33.99 |

| 4RH | 23.68 | 32.69 | 30.57 | 32.76 |

| 5RH | 20.73 | 31.83 | 28.45 | 32.04 |

| 6RH | 23.68 | 32.08 | 31.88 | 33.40 |

| 7RH | 21.08 | 29.81 | 28.33 | 30.70 |

| 8RH | 31.25 | 39.00 | 38.31 | 39.44 |

| 9RH | 23.00 | 35.23 | 30.54 | 35.60 |

| 10RH | 24.71 | 32.56 | 31.64 | 32.58 |

| 11RH | 27.22 | 35.63 | 34.10 | 35.75 |

| 12RH | 23.03 | 31.88 | 30.34 | 32.78 |

| 13RH | 25.64 | 34.59 | 32.98 | 35.35 |

| 14RH | 26.20 | 35.99 | 33.65 | 36.50 |

| 15RH | 21.57 | 32.06 | 27.85 | 30.93 |

| 16RH | 19.35 | 30.71 | 26.85 | 29.99 |

| 17RH | 19.96 | 30.14 | 26.08 | 29.16 |

Gibbs Free Energy Change [ΔGHDo(XRH•+)]

For clearance, structures and ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values of 17 XRH•+ releasing H• are presented in Figure 1. It is obvious that ΔGHD(XRH•+) of XRH•+ releasing H• vary significantly, from 19.35 (16RH•+) to 31.25 kcal/mol (8RH•+). All 17 XRH•+ have ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values ≫ 0 [ΔGHD(XRH•+) > 19.00 kcal/mol], indicating that the process of C–H bond cleavage from XRH•+ is thermodynamically unfavorable and hence, the reaction of XRH•+ releasing H• could not occur spontaneously at 298.15 K in acetonitrile. These results also show that substituents in the 4-position of XRH•+ have large effects on the ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values (varying by 11.9 kcal/mol). We tried to divide the substituent effect into two different parts, that is, the steric effect as well as the electronic effect, and study the influence on the hydrogen-atom-donating ability of XRH•+ but find no fundamental law or determining factor. For example, as for 7RH•+, 5RH•+, 6RH•+, and 8RH•+, the steric effect and electron-donating ability increase as the substituents change from CH3- (7RH), Et- (5RH), and iPr- (6RH) to tBu- (8RH). However, the Gibbs free energy order is ΔGHD(8RH•+) > ΔGHDo(6RH•+) > ΔGHD(7RH•+) > ΔGHDo(5RH•+). In conclusion, no simple correlations between the 4-substituent properties and the ΔGHD(XRH•+) values are found, which indicate that the influence of 4-substituents’ properties on the Gibbs free energy changes is rather complicated.

Figure 1.

Comparison of structures and ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values of the 17 XRH.

From Figure 1, it is found that the Gibbs free energy order is ΔGHDo(14RH•+) > ΔGHD(15RH•+) > ΔGHDo(16RH•+) when the substituent changes from 4-NMe2-Ph- and 4-NO2-Ph- to Ph-. The above phenomenon is not easily understandable, and intuitively, the ΔGoHD(16RH•+) value would be between the other two. We further analyze the intrinsic reason of the seemingly abnormal phenomenon. We find that ΔSHD(14RH•+) and ΔSHDo(16RH•+) are almost the same (24.99 and 25.14 cal mol–1 K–1, respectively), but the ΔSHD(15RH•+) (21.09 cal mol–1 K–1) is quite lower than ΔSo(14RH•+) and ΔSo(16RH•+). In all, the different entropy changes make ΔGHDo(15RH•+) be between ΔGHD(14RH•+) and ΔGHDo16RH•+).

If the ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values of 17 XRH•+ are compared with that of their parent Hantzsch ester radical cations (denoted as HEH2, ΔGHDo(HEH2) = 25.28 kcal/mol, calculated in this work) without any substituent in the 4-position (Figure 1), 3RH•+, 8RH•+, 11RH•+, 13RH•+, and 14RH•+ have larger ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values (25.64–31.25 kcal/mol) than HEH2, while others have smaller ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values (19.35–24.71 kcal/mol) than HEH2 (25.28 kcal/mol). It is well known that NADH (Scheme 1), which has the typical 1,4-dihydropyridine structure in the redox core same as XRH and HEH2,3−5 is an important redox coenzyme as a hydrogen and electron carrier in vivo.23−28Figure 1 also presents ΔGHDo(NADH•+) (23.90 kcal/mol, computed in this work), which was clearly lower than the ΔGHD(HEH2•+) value (25.28 kcal/mol), even though they all have the 1,4-dihydropyridine structure. ΔGHD(NADH•+) (23.90 kcal/mol) is rightly among the range of 17 ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values (19.35–31.25 kcal/mol). Since NADH•+ has excellent antioxidant activity,28 it is safe to infer that 17 XRH•+ should belong to excellent hydrogen atom donors. These data indicate that substituents on the 4-position and 2,3,5,6-positions have a significant effect on the thermodynamics of 1,4-dihydropyridine releasing H•, and the Gibbs free energies of the 1,4-dihydropyridine radical cation structure (DPH•+) releasing H• [ΔGHD(DPH•+)] may be between 19 and 32 kcal/mol.

For typical antioxidants (defined as YH in this work) such as ascorbic acid (AscH2), vitamin E (VE), 2,6-tBu2-4-CH3-PhOH (BHT), and the NADH coenzyme, the Gibbs free energy of YH releasing H• [denoted as ΔGHDo(YH)] reflects the antioxidant activity to a large extent.29 It is true that for some antioxidants with phenolic hydroxyl or polar hydroxyl in the molecular structure, such as AscH2, VE, and BHT, sometimes, the antioxidant process undergoes sequential proton loss electron transfer30 or proton-coupled electron transfer.29 As for XRH•+, the antioxidant activity experiences the hydrogen atom-transfer mechanism (HAT) to give stable XH+ directly. In this work, we focus on comparing the hydrogen-atom-donating ability between XRH•+ and common antioxidants in HAT.

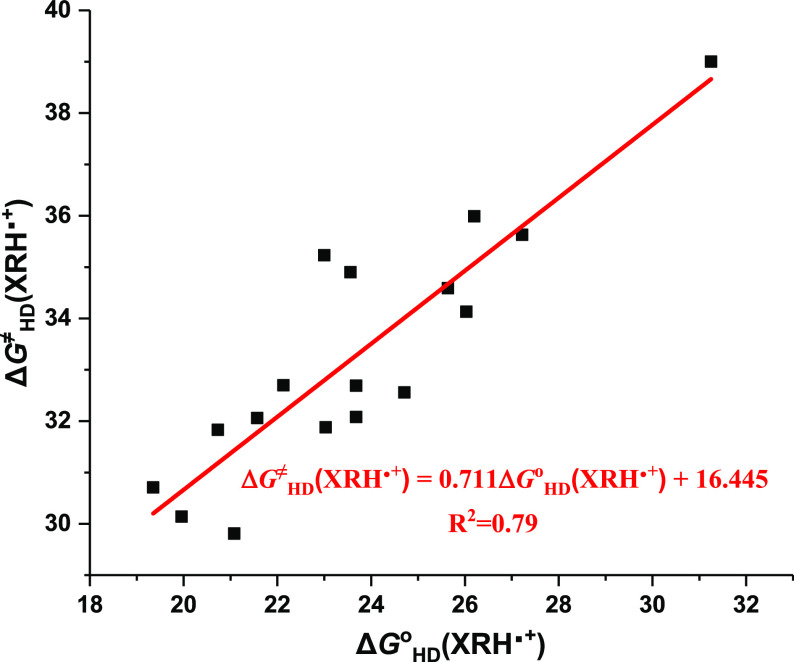

For comparison, we tried to obtain the Gibbs free energy changes of common excellent antioxidants (YH) releasing hydrogen atoms [denoted as ΔGHDo(YH), ΔGHD(YH) = BDEF(YH) – 4.9 kcal/mol29,31] and compare the ΔGHDo(YH) values with ΔGHD(XRH•+) in this work (Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, the ΔGHDo(YH) values of common antioxidants range from 59.1 kcal/mol for riboflavin to 81.3 kcal/mol for catechol, while the ΔGHD(XRH•+) values (19.35–31.25 kcal/mol) of 17 XRH•+ are significantly smaller than the ΔGHDo(YH) values (smaller by 27–62 kcal/mol). In conclusion, the thermodynamic data indicate that all 17 XRH•+ have potentially better antioxidant activity in chemical reactions than common antioxidants.

Figure 2.

Comparison of ΔGHDo(XRH•+) of 17 XRH•+ and ΔGHD(YH) of common antioxidants (YH) in solution at 298.15 K.

To assess the applicability of these XRH•+ in quenching common radicals (R•) in organic synthesis chemistry, we obtained the Gibbs free energies of common R• absorbing hydrogen atoms [denoted as ΔGHAo(R•), ΔGHA(R•) = −BDFE(R–H) + 4.9 kcal/mol29,31], as seen in Table 2. Since the charged molecules are very sensitive to solvents and their reactivity may depend on the polarity of the solvents, we compare the ΔGHAo(R•) with ΔGHD(XRH•+) in the same solvent (acetonitrile). As reported in the literature,29 the ΔGHAo(R•) values of the O–H bond (such as TEMPO•, 2,4,6-tBu3-PhO•, and tBu2NO•) range from 60.3 to 72.2 kcal/mol, the ΔGHA(R•) values of the N–H bond (such as PrNH•, Et2N•, and tBuNH•) range from 79.3 to 83.9 kcal/mol, and the ΔGHAo(R•) values of the M–H bond [such as CpFe(CO)2•, CpCr(CO)3•, Mn(CO)5•, and Re(CO)5•] range from 45.4 to 63.0 kcal/mol. Obviously, the ΔGHA(R•) values (45.4–83.9 kcal/mol) are all significantly higher than the ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values of 17 XRH•+ (19.35–31.25 kcal/mol), which indicate that the Gibbs free energy changes of R• quenching reactions by 17 XRH•+ (XRH•+ + R• → XR+ + RH) are large negative values [ΔGo(XRH•+/R•) ≪ 0]; therefore, the radical quenching reactions are thermodynamically favorable and very easy to happen in solution.

Table 2. Gibbs Free Energies of Common R• Absorbing Hydrogen Atoms [ΔGHAo(R•)] in Acetonitrile (kcal/mol)29.

| R–H | resulting radical types | solvents | ΔGHAo(R•)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEMPO• | O-radical | CH3CN | 61.6 |

| 2,4,6-tBu3-PhO• | O-radical | CH3CN | 72.2 |

| tBu2NO• | O-radical | CH3CN | 60.3 |

| PrNH• | N-radical | CH3CN | 83.7 |

| Et2N• | N-radical | CH3CN | 79.3 |

| tBuNH• | N-radical | CH3CN | 83.9 |

| C6H5–CH2• | C-radical | CH3CN | 82.1 |

| CpFe(CO)2• | Fe-radical | CH3CN | 45.4 |

| CpRu(CO)2• | Ru-radical | CH3CN | 53.3 |

| CpCr(CO)3• | Cr-radical | CH3CN | 56.6 |

| CpMo(CO)3• | Mo-radical | CH3CN | 57.5 |

| CpW(CO)3• | W-radical | CH3CN | 60.7 |

| Mn((CO)5• | Mn-radical | CH3CN | 57.9 |

| Re(CO)5• | Re-radical | CH3CN | 63.0 |

ΔGHAo(R•) = −BDFE(R–H) + 4.9 kcal/mol.29

Since we have obtained the Gibbs free energy of XRH•+ releasing R• [ΔGRDo(XRH•+) values] in our previous work,16 the ΔGRD(XRH•+) values of XRH•+ releasing R• range from −12.15 to 26.85 kcal/mol, while the ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values of XRH•+ releasing H• range from 29.81 to 39.00 kcal/mol. If the ΔGRD(XRH•+) and ΔGHDo(XRH•+) of one parent structure are compared, the margin value between them is denoted as ΔΔGo(H–R) [ΔΔGo(H–R) = ΔGHD(XRH•+) – ΔGRDo(XRH•+)]. The ΔΔGo(H–R) values range from −2.25 (16RH•+) to 38.58 kcal/mol (8RH•+). Among the 17 XRH•+ structures examined, the ΔΔGo(H–R) values of 13 XRH•+ (1RH•+–13RH•+) are greater than 15 kcal/mol, which means that the ΔGHD(XRH•+) value is very much higher than ΔGRDo(XRH•+) for 1RH•+–13RH•+. Further checking the structure, the substituents in 1RH•+–13RH•+ are nonaromatic substituents. That is to say, XRH•+ with nonaromatic substituents tend to release R• instead of H• to quench radicals. Since 4-substituted Hantzsch esters (XRH, Scheme 1) are known as dipine drugs, if dipine drugs with nonaromatic substituents are used to treat hypertensive and cardiovascular diseases, we should pay more attention to the possible alkylation of DNA or RNA and genotoxicity by dihydropyridine radical cations generated by a single electron oxidant or oxidoreductase in vivo. While the ΔΔGo(H–R) values of 4 XRH•+ (14RH•+–17RH•+) are less than 6.5 kcal/mol, the ΔΔGo(H–R) values of 14RH•+, 16 RH•+, and 17RH•+ are −0.65, −2.25, and −1.76 kcal/mol, respectively. The ΔΔGo(H–R) are negative values, which indicate that 14RH•+, 16 RH•+, and 17RH•+ tend to release H• instead of R• to quench radicals. From further analysis on the relevance between the chemical structure and ΔΔGo(H–R) values, it is evident that R substituents in 14RH•+, 16 RH•+, and 17RH•+ are aromatic substituents, that is, 4-NMe2-Ph-, Ph-, and 2-thiophene, respectively. Therefore, it is safe to say that whether XRH•+ is an excellent antioxidant is decided by the R substituents in the 4-position from thermodynamics. XRH•+ with nonaromatic substituents tend to release R• instead of H• to quench radicals. XRH•+ with aromatic substituents tend to release H• and be used as antioxidants, but not all aromatic substituted Hantzsch esters are excellent antioxidants, such as 15RH•+.

Activation Free Energy [ΔGHD≠(XRH•+)]

ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) is the characteristic physical parameter32 of XRH•+ and reflects the kinetic properties of XRH•+ releasing H• with no catalyst or substrate radicals. ΔGHD(XRH•+) values of 17 XRH•+ are presented in Figure 3. Obviously, the ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) values vary from 29.81 (7RH•+) to 39.00 kcal/mol (8RH•+), and the corresponding reaction rate constants (kH) range from 8.71 × 10–10 to 1.60 × 10–16 M–1 s–1 at 298.15 K, according to the Erying equation kH = (kBT/h) exp (−ΔG≠/RT).33

Figure 3.

Comparison of ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) among the 17 XRH•+ at 298.15 K.

If the ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) values of 17 XRH•+ (29.81–39.00 kcal/mol) are compared with that of their parent HEH2 [ΔGHD≠(HEH2) = 29.32 kcal/mol, computed in this work], it is found that all 17 ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) values are higher than ΔGHD(HEH2•+), which means that the R substituents in the 4-position make XRH•+ harder to release hydrogen atoms, despite the electronegativity, R• stability, steric hindrance, and so on.

From Figure 3, it is found that the activation free energy of the NADH radical cation releasing H• [ΔGHD≠(NADH•+), computed in this work] is 31.25 kcal/mol. The ΔGHD(NADH•+) value (31.25 kcal/mol) is higher than ΔGHD≠(HEH2) (29.32 kcal/mol), which indicates that HEH2•+ has better hydrogen-atom-donor reactivity than NADH•+ from the kinetics. Moreover, ΔGHD(NADH•+) (31.25 kcal/mol) is rightly among the 17 ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) values in the range of 29.81–39.00 kcal/mol. Since NADH•+ is an excellent radical quencher,28 17 XRH•+ should be excellent antioxidant reagents too. Nevertheless, the high activation free energies [ΔGHD(XRH•+) > 21 kcal/mol] indicate that releasing H• from all 17 XRH•+ is kinetically unfavorable spontaneous behavior and extremely slow in acetonitrile without any catalyst or hydrogen atom acceptors at room temperature. Considering the same 1,4-dihydropyridine core structure of XRH•+, HEH2•+, and NADH•+, the activation free energies of the 1,4-dihydropyridine radical cation structure (DPH•+) releasing H• [ΔGHD(DPH•+)] may be between 29 and 39 kcal/mol in acetonitrile.

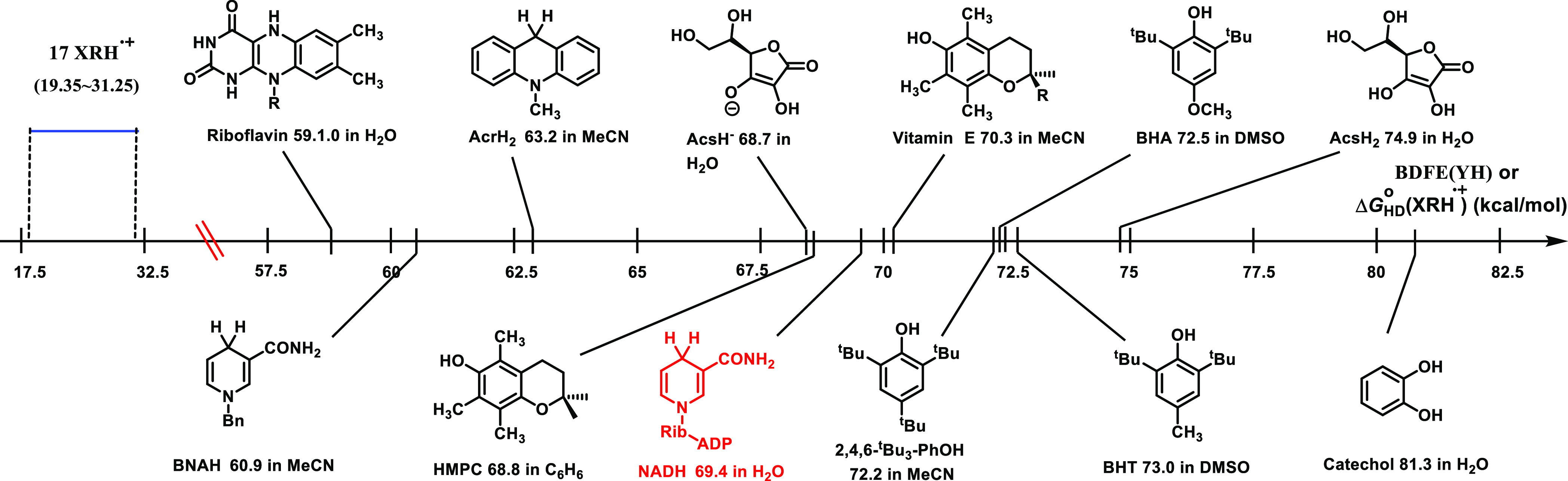

To further examine the interrelationship between thermodynamic driving forces and kinetic properties, the correlation between ΔGHDo(XRH•+) and ΔGHD(XRH•+) is illustrated in Figure 4. It is clear that there is a certain correlation between ΔGHDo(XRH•+) and ΔGHD(XRH•+), that is, ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) increases in company with the increase of ΔGHD(XRH•+). However, for all 17 XRH•+, no good linear correlation was found between ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) and ΔGHD(XRH•+).34 This correlation shows that the activation free energy is decided by complex factors and not the only factor of Gibbs free energy, although it is the important and decisive parameter. The linear correlation was also fitted to give the equation ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) = 0.711ΔGHD(XRH•+) + 16.445 (R2 = 0.79), which means that ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) can be roughly estimated when ΔGHD(XRH•+) are obtained.

Figure 4.

Correlation between the ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) and ΔGHD(XRH•+) of 17 XRH•+ releasing H•.

Changes of Entropy ΔSHDo(XRH•+) and ΔSHD(XRH•+)

The entropy changes and activation entropies of 17 XRH•+ releasing H• [denoted as ΔSHDo(XRH•+) and ΔSHD(XRH•+) in this work, respectively] are calculated from the corresponding enthalpies and Gibbs free energies (Table 3). From Table 3, we can see that ΔSHDo(XRH•+) vary from 20.56 (17RH•+) to 27.52 cal mol–1 K–1 (6RH•+), while ΔSHD(XRH•+) vary from −3.79 (15RH•+) to 4.45 cal mol–1 K–1 (6RH•+). It is found that ΔSHDo(XRH•+) are all positive values bigger than 20 cal mol–1 K–1, which indicates that the reaction process of XRH•+ releasing H• is in company with a large entropy increase. This is quite reasonable since the releasing H• reaction involves cleavage of one molecule to two segments, which increases the freedom of the system. On the other hand, the variation of ΔSHD(XRH•+) (−3.79–4.45 cal mol–1 K–1) is less than ±5 cal mol–1 K–1, indicating that transition states of XRH•+ do not undergo drastic structural changes compared with the initial state. In the elementary step of XRH•+ releasing H•, the C–H bond does not completely break at the transition state (TS), while the reaction products completely break to XR+ and H•. Therefore, the structure of TS is reactant-like instead of product-like. In addition, the XR+ and H• are charged structures and have a stronger solvation effect. On the basis of the above analysis, it is reasonable that ΔSHDo(XRH•+) are large positive (20.56–27.52 cal mol–1 K–1), but the ΔSHD(XRH•+) are very small close to 0 (−3.79–4.45 cal mol–1 K–1).

Table 3. Entropy Changes [ΔSHDo(XRH•+)] and Activation Entropies [ΔSHD(XRH•+)] of XRH•+ Releasing H• (unit: cal mol–1 K–1).

| XRH | ΔSHDo(XRH•+)a | ΔSHD≠(XRH•+)b | XRH | ΔSHDo(XRH•+)a | ΔSHD≠(XRH•+)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1RH | 27.17 | 1.48 | 10RH | 23.26 | 0.07 |

| 2RH | 24.28 | –0.60 | 11RH | 23.10 | 0.39 |

| 3RH | 25.26 | –0.45 | 12RH | 24.53 | 3.00 |

| 4RH | 23.15 | 0.24 | 13RH | 24.62 | 2.53 |

| 5RH | 25.91 | 0.72 | 14RH | 24.99 | 1.71 |

| 6RH | 27.52 | 4.45 | 15RH | 21.09 | –3.79 |

| 7RH | 24.32 | 2.99 | 16RH | 25.14 | –2.42 |

| 8RH | 23.69 | 1.47 | 17RH | 20.56 | –3.28 |

| 9RH | 25.27 | 1.23 |

ΔSHDo(XRH•+) = [ΔHHD(XRH•+) – ΔGHDo(XRH•+)]/T.

ΔSHD≠(XRH•+) = [ΔHHD(XRH•+) – ΔGHD≠(XRH•+)]/T.

Conclusions

This work focuses on the hydrogen-atom-donating ability of the key intermediate XRH•+ generated from 4-substituted Hantzsch ester (XRH). Four characteristic physical chemistry parameters of 17 XRH•+ releasing H•, ΔHHDo(XRH•+), ΔGHD(XRH•+), ΔHHD≠(XRH•+), and ΔGHD(XRH•+) were calculated using DFT and analyzed in detail. (1) The ΔGHDo(XRH•+) values are all positive values larger than 19.35 kcal/mol (19.35–31.25 kcal/mol), which means that it is very difficult for XRH•+ to release H• at 298.15 K spontaneously in the absence of the hydrogen atom capturer. Nevertheless, ΔGHD(XRH•+) values of 17 XRH•+ are significantly smaller than that of common antioxidants such as ascorbic acid, BHT, vitamin E, and the NADH coenzyme. (2) The ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) values span from 29.81 to 39.00 kcal/mol, and the cleavage of the C–H bond to release spontaneously H• in XRH•+ is extremely slow in acetonitrile at room temperature. (3) ΔGHD(XRH•+) increases in company with the increase of ΔGHDo(XRH•+), but no simple linear correlations are found because the influence of 4-substituent structures on ΔGHD(XRH•+) and ΔGHD≠(XRH•+) is rather complicated. (4) If R is a nonaromatic substituent, XRH•+ prefer to release R• to quench radicals; If R is an aromatic substituent, XRH•+ prefer to release H• to quench radicals, but not all aromatic substituted Hantzsch esters are excellent antioxidants. The data and calculation method presented in this work would be helpful in applications of XRH•+ as antioxidants and free-radical scavengers in organic chemistry and other related areas.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the NSFC cultivation project of Jining Medical University (JYP2018KJ18 and JYP2019KJ25), the doctoral scientific research foundation of Jining Medical University (600841002), and the College Students’ Innovative Training Plan Program of Jining Medical University (cx2020106).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c03872.

Coordinates of optimized structures and IRC energies of each XRH•+ (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Gao S.; Yan N. Structural Basis of the Modulation of the Voltage-Gated Calcium Ion Channel Cav1.1 by Dihydropyridine Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 3131–3137. 10.1002/anie.202011793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mulder P.; Litwinienko G.; Lin S.; MacLean P. D.; Barclay L. R. C.; Ingold K. U. The L-Type Calcium Channel Blockers, Hantzsch 1,4-Dihydropyridines, Are Not Peroxyl Radical-Trapping, Chain-Breaking Antioxidants. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 79–85. 10.1021/tx0502591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Huang J.; Buckley N. A.; Isoardi K. Z.; Chiew A. L.; Isbister G. K.; Cairns R.; Brown J. A.; Chan B. S. Angiotensin Axis Antagonists Increase the Incidence of Haemodynamic Instability in Dihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blocker Poisoning. Clin. Toxicol. 2021, 59, 464–471. 10.1080/15563650.2020.1826504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mendez S. R.; Frank R. C.; Stevenson E. K.; Chung M.; Silverman M. G. Dihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockers and the Risk of Severe COVID-19. Chest 2021, 160 (1), 89–93. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pan X.; Li R.; Guo H.; Zhang W.; Xu X.; Chen X.; Ding L. Dihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockers Suppress the Transcription of PD-L1 by Inhibiting the Activation of STAT1. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 539261. 10.3389/fphar.2020.539261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Khot S.; Auti P. B.; Khedkar S. A. Diversified Synthetic Pathway of 1, 4-Dihydropyridines: A Class of Pharmacologically Important Molecules. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 135–149. 10.2174/1389557520666200807130215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sorkin E. M.; Clissold S. P.; Brogden R. N. Nifedipine. Drugs 1985, 30, 182–274. 10.2165/00003495-198530030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Pi D.; Zhou H.; Cui P.; He R.; Sui Y. Silver-Catalyzed Biomimetic Transfer Hydrogenation of N-Heteroaromatics with Hantzsch Esters as NADH Analogues. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 3976–3979. 10.1002/slct.201700327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhu X.-Q.; Zou H.-L.; Yuan P.-W.; Liu Y.; Cao L.; Cheng J.-P. A Detailed Investigation into the Oxidation Mechanism of Hantzsch 1,4-dihydropyridines by Ethyl α-cyanocinnamates and Benzyl-idenemalononitriles. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 2000, 1857–1861. 10.1039/b003404p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zhu X.-Q.; Wang H.-Y.; Wang J.-S.; Liu Y.-C. Application of NAD(P)H Model Hantzsch 1,4-Dihydropyridine as a Mild Reducing Agent in Preparation of Cyclo Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 344–347. 10.1021/jo001434f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhu X.-Q.; Liu Y.-C.; Cheng J.-P. Which Hydrogen Atom Is First Transferred in the NAD(P)H Model Hantzsch Ester Mediated Reactions via One-Step and Multistep Hydride Transfer?. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 8980–8981. 10.1021/jo9905571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cheng J.-P.; Lu Y.; Zhu X.-Q.; Sun Y.-K.; Bi F.; He J. Heterolytic and Homolytic N-H Bond Dissociation Energies of 4-Substituted Hantzsch 2,6-Dimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridines and the Effect of One-Electron Transfer on the N-H Bond Activation. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 3853–3857. 10.1021/jo991145v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhu X.-Q.; Zhao B.-J.; Cheng J.-P. Mechanisms of the Oxidations of NAD(P)H Model Hantzsch 1,4-Dihydropyridines by Nitric Oxide and Its Donor N-Methyl-N-nitrosotoluene-p-sulfonamide. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 8158–8163. 10.1021/jo000484h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Garden S. J.; Guimarǎes C. R. W.; Corréa M. B.; Oliveira C. A. F.; Angelo da Cunha Pinto A. C.; Alencastro R. B. Synthetic and Theoretical Studies on the Reduction of Electron Withdrawing Group Conjugated Olefins Using the Hantzsch 1,4-Dihydropyridine Ester. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 8815–8822. 10.1021/jo034921e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gao Y.; Wang B.; Gao S.; Zhang R.; Yang C.; Sun Z.; Liu Z. Design and Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridine and Cinnamic Acid Esters and Their Antioxidant Properties. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2016, 32, 594–599. 10.1007/s40242-016-6047-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b López-Alarcón C.; Navarrete P.; Camargo C.; Squella J. A.; Núñez-Vergara L. J. Reactivity of 1,4-Dihydropyridines toward Alkyl, Alkylperoxyl Radicals, and ABTS Radical Cation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003, 16, 208–215. 10.1021/tx025579o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Aruoma O. I.; Smith C.; Cecchini R.; Evans P. J.; Halliwell B. Free Radical Scavenging and Inhibition of Lipid Peroxidation by Beta-blockers and by Agents that Interfere with Calcium Metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1991, 42, 735–743. 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mak I. T.; Weglicki W. B. Comparative Antioxidant Activities of Propranolol, Nifedipine, Verapamil, and Diltiazem against Sarcolemmal Membrane Lipid Peroxidation. Circ. Res. 1990, 66, 1449–1452. 10.1161/01.res.66.5.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mason R. P.; Mak I. T.; Trumbore M. W.; Mason P. E. Antioxidant Properties of Calcium Antagonists Related to Membrane Biophysical Interactions. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999, 84, 161–221. 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Diaz-Araya G.; Godoy L.; Naranjo L.; Squella J. A.; Letelier M. E.; Núñez-Vergara L. J. Antioxidant Effects of 1,4-dihydropyridine and Nitroso Aryl Derivatives on the Fe+3/ascorbatestimulated Lipid Peroxidation in Rat Brain Slices. Gen. Pharmacol. 1998, 31, 385–391. 10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lupo E.; Locher R.; Weisser B.; Velter W. Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Calcium Antagonists against LDL Oxidation Compared with Alpha-tocopherol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 203, 1803–1808. 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Napoli C.; Chiariello M.; Palumbo G.; Ambrosio G. Calcium-channel Blockers Inhibit Human Lowdensity Lipoprotein Oxidation by Oxygen Radicals. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 1996, 10, 417–424. 10.1007/bf00051106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sobal G.; Menzel E. J.; Sinzinger H. Calcium Antagonists as Inhibitors of in Vitro Low-density Lipoprotein Oxidation and Glycation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 61, 373–379. 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Vele̅na A.; Zilbers J.; Dubers G. Derivatives of 1,4-Dihydropyridines as Modulators of Ascorbate-induced Lipid Peroxidation and High-amplitude Swelling of Mitochondria, Caused by Ascorbate, Sodium Linoleate and Sodium Pyrophosphate. Cell Biochem. Funct. 1999, 17, 237–252. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mak I. T.; Boheme P.; Weglicki W. B. Antioxidant Effects of Calcium Channel Blockers against Free Radical Injury in Endothelial Cells. Correlation of Protection with Preservation of Glutathione Levels. Circ. Res. 1992, 70, 1099–1103. 10.1161/01.res.70.6.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mak I. T.; Boheme P.; Weglicki W. B. Protective Effects of Calcium Channel Blockers Against Free Radical-impaired Endothelial Cell Proliferation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995, 50, 1531–1534. 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reviews:; a Wang P.-Z.; Chen J.-R.; Xiao W.-J. Hantzsch esters: an Emerging Versatile Class of Reagents in Photoredox Catalyzed Organic Synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 6936–6951. 10.1039/c9ob01289c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ye S.; Wu J. 4-Substituted Hantzsch Esters as Alkylation Reagents in Organic Synthesis. Acta Chim. Sin. 2019, 77, 814–831. 10.6023/a19050170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Milligan J. A.; Phelan J. P.; Badir S. O.; Molander G. A. Recent Advances in Alkyl Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation by Nickel/Photoredox Cross-Coupling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6152–6163. 10.1002/anie.201809431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wangelin A. J.; Konev M. O.; Cardinale L. Photoredox-Catalyzed Addition of Carbamoyl Radicals to Olefins: A 1,4-Dihydropyridine Approach. Chem.—Eur. J. 2020, 26, 8239–8243. 10.1002/chem.202002410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang J.; Shao Z.; Tan K.; Tang R.; Zhou Q.; Xu M.; Li Y.-M.; Shen Y. Synthesis of Amino Acids by Base-enhanced Photoredox Decarboxylative Alkylation of Aldimines. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 9944–9954. 10.1021/acs.joc.0c01246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liu L.; Jiang P.; Liu Y.; Du H.; Tan J. Direct Radical Alkylation and Acylation of 2H-indazoles Using Substituted Hantzsch Esters as Radical Reservoirs. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 2278–2283. 10.1039/d0qo00507j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Schwarz J. L.; Huang H.-M.; Paulisch T. O.; Glorius F. Dialkylation of 1,3-Dienes by Dual Photoredox and Chromium Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 1621–1627. 10.1021/acscatal.9b04222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhu D.-L.; Wu Q.; Li H.-Y.; Li H.-X.; Lang J.-P. Hantzsch Ester as a Visible-Light Photoredox Catalyst for Transition-Metal-Free Coupling of Arylhalides and Arylsulfinates. Chem.—Eur. J. 2020, 26, 3484–3488. 10.1002/chem.201905281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li J.; Yang X.-E.; Wang S.-L.; Zhang L.-L.; Zhou X.-Z.; Wang S.-Y.; Ji S.-J. Visible-Light-Promoted Cross-Coupling Reactions of 4-Alkyl-1,4-dihydropyridines with Thiosulfonate or Selenium Sulfonate: A Unified Approach to Sulfides, Selenides, and Sulfoxides. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 4908–4913. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Du H.-W.; Sun J.; Gao Q.-S.; Wang J.-Y.; Wang H.; Xu Z.; Zhou M.-D. Synthesis of Monofluoroalkenes through Visible-Light-Promoted Defluorinative Alkylation of gem-Difluoroalkenes with 4-Alkyl-1,4-dihydropyridines. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 1542–1546. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c00134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S.; Kumon T.; Angnes R. A.; Sanchez M.; Xu B.; Hammond G. B. Synthesis of Alkyl Halides from Aldehydes via Deformylative Halogenation. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3848–3854. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Angnes R. A.; Potnis C.; Liang S.; Correia C. R. D.; Hammond G. B. Photoredox-Catalyzed Synthesis of Alkylaryldiazenes: Formal Deformylative C-N Bond Formation with Alkyl Radicals. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 4153–4164. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b03341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wang J.; Pang Y.-B.; Tao N.; Zeng R.-S.; Zhao Y. Mn-Enabled Radical-Based Alkyl-Alkyl Cross-Coupling Reaction from 4-Alkyl-1,4- dihydropyridines. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 15315–15322. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b02323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhang K.; Lu L.-Q.; Jia Y.; Wang Y.; Lu F.-D.; Pan F.; Xiao W.-J. Exploration of a Chiral Cobalt Catalyst for Visible-Light-Induced Enantioselective Radical Conjugate Addition. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 131, 13509–13513. 10.1002/ange.201907478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang X.; Li H.; Qiu G.; Wu J. Substituted Hantzsch Esters as Radical Reservoirs with the Insertion of Sulfur Dioxide under Photoredox Catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2062–2065. 10.1039/c8cc10246e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Phelan J. P.; Lang S. B.; Sim J.; Berritt S.; Peat A. J.; Billings K.; Fan L.; Molander G. A. Open-Air Alkylation Reactions in Photoredox-Catalyzed DNA-Encoded Library Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3723–3732. 10.1021/jacs.9b00669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Leeuwen T.; Buzzetti L.; Perego L. A.; Melchiorre P. A Redox-Active Nickel Complex that Acts as an Electron Mediator in Photochemical Giese Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4953–4957. 10.1002/anie.201814497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Goti G.; Bieszczad B.; Vega-Penaloza A.; Melchiorre P. Stereocontrolled Synthesis of 1,4-Dicarbonyl Compounds by Photochemical Organocatalytic Acyl Radical Addition to Enals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1213–1217. 10.1002/anie.201810798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nakajima K.; Zhang Y.; Nishibayashi Y. Alkylation Reactions of Azodicarboxylate Esters with 4-Alkyl-1,4-Dihydropyridines under Catalyst-Free Conditions. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 4642–4645. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen G.-B.; Xie L.; Yu H. Y.; Liu J.; Fu Y.-H.; Yan M. Theoretical Investigation on the Nature of 4-Substituted Hantzsch Esters as Alkylation Agents. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 31425–31434. 10.1039/d0ra06745h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Becke A. D. Density-functional Thermochemistry. 3. the Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Stephens P. J.; Devlin F. J.; Chabalowski C. F.; Frisch M. J. Ab-initio Calculation of Vibrational Absorption and Circular-dichroism Spectra using Density-functional Force-fields. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 11623–11627. 10.1021/j100096a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ditchfield R.; Hehre W. J.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. 9. Extended Gaussian-type Basis for Molecular-orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 724. 10.1063/1.1674902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Hehre W. J.; Ditchfield R.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. 12. Further Extensions of Gaussian-type Basis Sets for Use in Molecular-orbital Studies of Organic-molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 2257. 10.1063/1.1677527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Hariharan P. C.; Pople J. A. Influence of Polarization Functions on Molecular-orbital Hydrogenation Energies. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1973, 28, 213–222. 10.1007/bf00533485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Ehrlich S.; Goerigk L. Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; et al. Gaussian 09; Gaussian, Inc., 2013.

- Lu T.; Chen F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ali M. A.; Hassan A.; Sedenho G. C.; Gonçalves R. V.; Cardoso D. R.; Crespilho F. N. Operando Electron Paramagnetic Resonance for Elucidating the Electron Transfer Mechanism of Coenzymes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 16058–16064. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b01160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zielonka J.; Marcinek A.; Adamus J.; Gȩbicki J. Direct Observation of NADH Radical Cation Generated in Reactions with One-Electron Oxidants. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 9860–9864. 10.1021/jp035803y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Saura P.; Kaila V. R. I. Energetics and Dynamics of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in the NADH/FMN Site of Respiratory Complex I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5710–5719. 10.1021/jacs.8b11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Li F.; Li Y.; Sun L.; Chen X.; An X.; Yin C.; Cao Y.; Wu H.; Song H. Modular Engineering Intracellular NADH Regeneration Boosts Extracellular Electron Transfer of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 885–895. 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Matsuzaki S.; Kotake Y.; Humphries K. M. Identification of Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain-Mediated NADH Radical Formation by EPR Spin-Trapping Techniques. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 10792–10803. 10.1021/bi201714w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Crane E. J.; Parsonage D.; Poole L. B.; Claiborne A. Analysis of the Kinetic Mechanism of Enterococcal NADH Peroxidase Reveals Catalytic Roles for NADH Complexes with both Oxidized and Two-Electron-Reduced Enzyme Forms. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 14114–14124. 10.1021/bi00043a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Murataliev M. B.; Klein M.; Fulco A.; Feyereisen R. Functional Interactions in Cytochrome P450BM3: Flavin Semiquinone Intermediates, Role of NADP(H), and Mechanism of Electron Transfer by the Flavoprotein Domain. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 8401–8412. 10.1021/bi970026b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Birrell J. A.; Yakovlev G.; Hirst J. Reactions of the Flavin Mononucleotide in Complex I: A Combined Mechanism Describes NADH Oxidation Coupled to the Reduction of APAD+, Ferricyanide, or Molecular Oxygen. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 12005–12013. 10.1021/bi901706w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Fukuzumi S.; Inada O.; Suenobu T. Mechanisms of Electron-Transfer Oxidation of NADH Analogues and Chemiluminescence. Detection of the Keto and Enol Radical Cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4808–4816. 10.1021/ja029623y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yano T.; Rahimian M.; Aneja K. K.; Schechter N. M.; Rubin H.; Scott C. P. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Type II NADH-Menaquinone Oxidoreductase Catalyzes Electron Transfer through a Two-Site Ping-Pong Mechanism and Has Two Quinone-Binding Sites. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1179–1190. 10.1021/bi4013897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Afanasyeva M. S.; Taraban M. B.; Purtov P. A.; Leshina T. V.; Grissom C. B. Magnetic Spin Effects in Enzymatic Reactions: Radical Oxidation of NADH by Horseradish Peroxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8651–8658. 10.1021/ja0585735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Xie T.; Wu Z.; Gu J.; Guo R.; Yan X.; Duan H.; Liu X.; Liu W.; Liang L.; Wan H.; Luo Y.; Tang D.; Shi H.; Hu J. The Global Motion Affecting Electron Transfer in Plasmodium Falciparum type II NADH Dehydrogenases: a Novel Non-competitive Mechanism for Quinoline Ketone Derivative Inhibitors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 18105–18118. 10.1039/c9cp02645b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Matsumura H.; Matsuda K.; Nakamura N.; Ohtaki A.; Yoshida H.; Kamitori S.; Yohda M.; Ohno H. Monooxygenation by a Thermophilic Cytochrome P450via Direct Electron Donation from NADH. Metallomics 2011, 3, 389–395. 10.1039/c0mt00079e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Matsuo T.; Mayer J. M. Oxidations of NADH Analogues by cis-[RuIV(bpy)2(py)(O)]2+ Occur by Hydrogen-Atom Transfer Rather than by Hydride Transfer. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 2150–2158. 10.1021/ic048170q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhu X.-Q.; Yang Y.; Zhang M.; Cheng J.-P. First Estimation of C4-H Bond Dissociation Energies of NADH and Its Radical Cation in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 15298–15299. 10.1021/ja0385179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Olek R. A.; Ziolkowski W.; Kaczor J. J.; Greci L.; Popinigis J.; Antosiewicz J. Antioxidant Activity of NADH and its Analogue-An in Vitro study. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 37, 416–421. 10.5483/bmbrep.2004.37.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren J. J.; Tronic T. A.; Mayer J. M. Thermochemistry of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reagents and its Implications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6961–7001. 10.1021/cr100085k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Litwinienko G.; Ingold K. U. Abnormal Solvent Effects on Hydrogen Atom Abstraction. 2. Resolution of the Curcumin Antioxidant Controversy. The Role of Sequential Proton Loss Electron Transfer. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 5888–5896. 10.1021/jo049254j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Litwinienko G.; Ingold K. U. Abnormal Solvent Effects on Hydrogen Atom Abstractions. 1. The Reactions of Phenols with 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (dpph•) in Alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 3433–3438. 10.1021/jo026917t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bordwell F. G.; Cheng J.-P.; Harrelson J. A. Homolytic Bond Dissociation Energies in Solution from Equilibrium Acidity and Electrochemical Data. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 1229–1231. 10.1021/ja00212a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang X.-M.; Bruno J. W.; Enyinnaya E. Hydride Affinities of Arylcarbenium Ions and Iminium Ions in Dimethyl Sulfoxide and Acetonitrile. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 4671–4678. 10.1021/jo980120d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zhu X.-Q.; Zhou J.; Wang C.-H.; Li X.-T.; Jing S. Actual Structure, Thermodynamic Driving Force, and Mechanism of Benzofuranone-Typical Compounds as Antioxidants in Solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 3588–3603. 10.1021/jp200095g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y.-H.; Shen G.-B.; Li Y.; Yuan L.; Li J.-L.; Li L.; Fu A.-K.; Chen J.; Chen B.-L.; Zhu L.; Zhu X.-Q. Realization of Quantitative Estimation for Reaction Rate Constants Using only One Physical Parameter for Each Reactant. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 904–925. 10.1002/slct.201601799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhu X.-Q.; Li X.-T.; Han S.-H.; Mei L.-R. Conversion and Origin of Normal and Abnormal Temperature Dependences of Kinetic Isotope Effect in Hydride Transfer Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 4774–4783. 10.1021/jo3005952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shen G.-B.; Xia K.; Li X.-T.; Li J.-L.; Fu Y.-H.; Yuan L.; Zhu X.-Q. Prediction of Kinetic Isotope Effects for Various Hydride Transfer Reactions Using a New Kinetic Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 1779–1799. 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhu X.-Q.; Deng F.-H.; Yang J.-D.; Li X.-T.; Chen Q.; Lei N.-P.; Meng F.-K.; Zhao X.-P.; Han S.-H.; Hao E.-J.; Mu Y.-Y. A Classical but New Kinetic Equation for Hydride Transfer Reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 6071–6089. 10.1039/c3ob40831k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li Y.; Zhu X.-Q. Theoretical Predictiong of Activation Free Energies of Various Hydride Self-Exchange Reactions in Acetonitrile at 298 K. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 872–885. 10.1021/acsomega.7b01911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.