Abstract

Background

Besides feeding on blood, females of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae sensu lato readily feed on natural sources of plant sugars. The impact of toxic secondary phytochemicals contained in plant-derived sugars on mosquito physiology and the development of Plasmodium parasites remains elusive. The focus of this study was to explore the influence of the alkaloid ricinine, found in the nectar of the castor bean Ricinus communis, on the ability of mosquitoes to transmit Plasmodium falciparum.

Methods

Females of Anopheles gambiae and its sibling species Anopheles coluzzii were exposed to ricinine through sugar feeding assays to assess the effect of this phytochemical on mosquito survival, level of P. falciparum infection and growth rate of the parasite.

Results

Ricinine induced a significant reduction in the longevity of both Anopheles species. Ricinine caused acceleration in the parasite growth rate with an earlier invasion of the salivary glands in both species. At a concentration of 0.04 g l−1 in An. coluzzii, ricinine had no effect on mosquito infection, while 0.08 g l−1 ricinine-5% glucose solution induced a 14% increase in An. gambiae infection rate.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings reveal that consumption of certain nectar phytochemicals can have unexpected and contrasting effects on key phenotypic traits that govern the intensity of malaria transmission. Further studies will be required before concluding on the putative role of ricinine as a novel control agent, including the development of ricinine-based toxic and transmission-blocking sugar baits. Testing other secondary phytochemicals in plant nectar will provide a broader understanding of the impact which plants can have on the transmission of vector-borne diseases.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13071-021-04992-z.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, Anopheles coluzzii, Anopheles gambiae, Ricinine, Malaria transmission, Transmission-blocking strategies

Background

Human malaria is a global disease caused by parasites of the genus Plasmodium, which are transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes. Despite substantial control progress in the last 2 decades, malaria remains a major cause of morbidity and infant mortality, with an estimated 229 million cases and 409,000 deaths in 2019, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Improving existing and available tools, such as impregnated bed nets, is essential in the immediate future; however, there is also an urgent need for the implementation of alternative solutions to achieve long-term control [2]. One approach is to disrupt the parasite development in mosquito vectors following blood-feeding on a vaccinated or drug-treated patient, i.e. transmission-blocking drugs or vaccines (TBD/V) [3].

The administration of TBD/V is not intended to protect or clear infected people, but to prevent the development of the parasite within the mosquito vector. When ingested through a blood meal, the drugs or antibodies inhibit parasite development, thereby reducing or blocking malaria transmission from the mosquito to a human host [4]. Besides blood-feeding, the delivery of a transmission-blocking agent into a mosquito host can occur through mosquito sugar-feeding and/or contact [5–7]. Regarding the latter delivery route, Paton et al. [8] showed that Anopheles exposure to atovaquone through treated surfaces before or shortly after Plasmodium falciparum infection can result in a full parasite arrest in the mosquito midgut.

Although female mosquitoes are well-known blood-feeders, sugar, obtained from floral and extra-floral nectaries, fruits and honeydew and phloem sap, is an important part of their diet and significantly affects the life history and transmission potential of malaria vectors [9–11]. From 1949 to 1968, Terzian et al. [12] took advantage of mosquito sugar feeding to test the sporontocidal activity of a number of synthetic antimalarial drugs on the bird malaria parasite Plasmodium gallinaceum in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Further studies later confirmed that antimalarial drugs, such as cycloguanil or pyrimethamine, have significant sporontocidal activity against P. falciparum in freshly infected mosquitoes following imbibement of the test compounds mixed in a sucrose solution [13]. In contrast to administration via the blood meal, which allows enzymatic transformation by the vertebrate host, this method allows for the direct analysis of the effects of the primary drug or its known metabolites. Another major advantage of this approach is that it does not require extensive drug safety assessment as part of substantial clinical trials in humans. Besides synthetic antimalarial drugs, attention could be given to phytochemicals with similar properties.

Some plant nectars contain secondary metabolites that can limit insect infection by pathogens [14, 15]. Considering the potential of natural plant extracts to block malaria transmission during mosquito blood-feeding [16, 17], toxic secondary metabolites from plants, including nectar compounds, may similarly affect the development of malaria parasites within the mosquitoes. For instance, Anopheles coluzzii females that fed on the flowering ornamental plant Thevetia neriifolia were less likely to carry sporozoites after an infectious meal compared to females that had fed on fruits of Lannea microcarpa or the ornamental plant Barleria lupulina [18]. A better understanding of the effects of plants on mosquito vector-malaria parasites interactions can therefore potentially give rise to novel control strategies, such as the development of transmission-blocking sugar baits [5, 6].

Besides possible prophylactic or therapeutic properties against pathogens within mosquitoes, another possible benefit of plant secondary metabolites could be their adverse effects on other key transmission traits, such as mosquito lifespan. Extracts of the castor bean (Ricinus communis, Euphorbiaceae) contain the alkaloid ricinine, which is present in R. communis nectar, and have strong insecticidal [19, 20] and antimicrobial [21–23] activities, including a newly reported effect against Plasmodium berghei in mice. Thus, extracts of R. communis are a promising candidate for the development of transmission-blocking drugs delivered through mosquito sugar meals.

The current study aimed at evaluating the effect of ricinine on the development of P. falciparum in two major malaria vectors, namely Anopheles gambiae and An. coluzzii. Mosquito females were challenged with sympatric field isolates of P. falciparum (five distinct isolates in total) using direct membrane feeding assays, and through a series of experiments, the effects of ricinine on (i) mosquito competence for P. falciparum, (ii) the timing of oocyst rupture and sporozoite dissemination and (iii) female survival were examined.

Methods

Mosquito strains

Laboratory-reared An. gambiae and An. coluzzii were obtained from outbred colonies established in 2012 that have been repeatedly replenished with F1 from wild-caught females collected in Soumousso (11°23′14′′N, 4°24′42′′W) and the Kou Valley (11°24′N, 4°24′59′′W) and identified by SINE PCR [23]. Mosquitoes were held in 30 × 30 × 30-cm mesh-covered cages under standard insectary conditions (12 h:12 h light:dark [L:D], 27 ± 2 °C, 70 ± 5% relative humidity). Females were maintained on rabbit blood by direct feeding (protocol approved by the national committee of Burkina Faso; IRB registration #00004738 and FWA 00007038) and adult males and females fed with a 5% glucose solution. Larvae were reared at a density of about 300 first-instar larvae in 700 ml of water in plastic trays and fed with Tetramin Baby Fish Food (Tetrawerke, Melle, Germany).

Ricinine detection in nectar

Naturally occurring levels of ricinine in R. communis nectar were estimated by collecting samples from seven plants cultivated at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and from three plants from the wild populations of R. communis around Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Plants from Kew were sampled during June and July 2016, and plants from Bobo-Dioulasso were sampled during August 2018. Extracts were analysed by liquid chromatography (LC)-electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy (ESIMS) and UV spectroscopy using a Thermo Fisher Velos Pro LC-MS. Samples (5 μl) were injected directly into a Phenomenex Luna C18 (2) column (150 Å–3 mm i.d., 3 μm particle size at 400 μl min−1 maintained at 30 °C and eluted using a linear gradient of 90:0:10 (t = 0 min) to 0:90:10 (t = 20–25 min), returning to 90:0:10 (t = 27–30 min) with water:methanol:1% formic acid in acetonitrile, respectively. Compounds were detected on a Thermo Fisher Velos Pro Dual-Pressure Linear Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer. A peak corresponding to ricinine eluted after 5.60 min with m/z = 165 [M + H]+ and 329 [2 M + H]+, consistent with a ricinine standard having a molecular formula of C8H8N2O2.

Ricinine was quantified using the LC-MS method above against an authentic ricinine standard obtained in our laboratories as described below. The mean concentration of ricinine in nectar was determined to be approximately 40 ppm (0.04 g l−1), with the maximum observed concentration exceeding 100 ppm. To test the effect of ricinine in mosquito diet on survival and parasite development, a medium (40 ppm) and a high concentration (80 ppm) of ricinine were incorporated into sugar feeds. The medium concentration (40 ppm) was considered ecologically relevant as it has previously been used in studies of female An. gambiae survival after feeding on ricinine in sugar solutions [19, 20].

Ricinine isolation

Ricinine for the experiments described in the current study was isolated from seeds of R. communis, which have high concentrations of ricinine [24]. Using a protocol for ricinine extraction established at Kew, seeds (200 g) were split open, ground using a mortar and pestle and then boiled in 1 l of distilled water. The extract was then vacuum filtered with a coarse filter paper, which separated the seed remains from the liquid. The filtrate was re-filtered with a finer grade filter paper (Whatman No. 1) and then extracted with chloroform (100 ml) in a separating funnel and shaken for 1 min. This was left to separate for 1–2 h. The chloroform was then run off and another portion of chloroform (100 ml) added, shaken and left to separate. This process was repeated two additional times. After the last portion of chloroform was run off, the remaining aqueous layer was centrifuged for at least 20 min at 2000 rpm for further separation of chloroform and the aqueous layer. The combined chloroform extracts were evaporated to dryness under vacuum on a Buchi Rotovap (Buchi UK Ltd., Newmarket, UK) and recrystallised from distilled water. Crystals were collected by vacuum filtration and left to dry in a desiccator. The compound identity was confirmed by HPLC-HRMS (experimental [+] m/z = 165.0652, calculated for C8 H9 O2 N2+ = 165.0658; uv: λmax 255, 306 nm) and by comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR spectrum acquired in MeOH-d4 at 30 °C recorded on a Bruker Avance 400=MHz spectrometer using standard pulse sequences and parameters, according to Souza et al. [25].

Preparation of the ricinine solutions and oral administration to mosquitoes

Two distinct ricinine solutions were prepared by mixing 1 l of a 5% glucose solution with either 0.04 g or 0.08 g of ricinine powder. These two solutions, at concentrations of 0.04 g l−1 and 0.08 g l−1, were solubilised in 5 ml of pure DMSO (DMSO, Honeywell, Germany). DMSO was also added to the 5% glucose control solution. The ricinine and control solutions were kept at 4 °C. Upon emergence, batches of female mosquitoes were randomly offered the treatment for 2 to 3 consecutive days through cotton pads soaked in either the 5% glucose control solution or alternatively the 0.04 g l−1 or the 0.08 g l−1 of ricinine and 5% glucose solution and placed on top of the mosquito cages. The cotton pads were changed daily. On day 3, the cotton pads were removed from the cages and mosquitoes deprived of food for 24 h prior to the infection. Given the daily frequency of mosquito sugar feeding at 27 °C (i.e. about 75% [26]) by 2–3 days, all mosquitoes would have acquired their sugar meal treatment at least once. Male and female mosquitoes were kept together to ensure insemination. On day 4, females were transferred to 500-ml paper cups at a density of 80 mosquitoes for infection.

Parasite isolates and mosquito experimental infection

Female mosquitoes (An. gambiae or An. coluzzii, depending on availability, see below) were fed with blood drawn from naturally P. falciparum gametocyte-infected patients recruited among 5–12-year-old school children in villages surrounding Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, using Direct membrane feeding assays (DMFA) as previously described [18, 27]. Briefly, thick blood smears were taken from each volunteer, air-dried, Giemsa-stained and examined by microscopy for the presence of P. falciparum at the IRSS laboratory in Bobo-Dioulasso. Asexual trophozoite parasite stages were counted against 200 leucocytes, while infectious gametocyte stages were counted against 1000 leukocytes. Children with asexual parasitaemia of > 1000 parasites per microlitre (estimated based on an average of 8000 leucocytes ml−1) were treated in accordance with national guidelines. Asymptomatic P. falciparum gametocyte-positive children were recruited for the study. Blood from gametocyte isolates was collected by venipuncture in heparinized tubes. Five distinct parasite isolates (named hereafter A, B, C, D and E), with respective gametocytaemia of 72, 144, 672, 264 and 88 gametocytes µl−1 of blood, were used for the experimental infections. DMFA was performed using whole donor blood (i.e. no serum replacement) [18]. Three-to-four-day-old female mosquitoes held in the paper cups (see above) were allowed to feed on this blood for 1 h. Non-fed or partially fed females were removed and discarded, while the remaining fully engorged mosquitoes were kept in a biosafety room under the same standard conditions (12 h:12 h L: D, 27 ± 2 °C, 70 ± 5% relative humidity). After infection, fully engorged mosquitoes were returned to 30 × 30 × 30-cm mesh-covered cages and provided their assigned treatment (i.e. 5% glucose or ricinine solution). Mosquito females thus received their treatment both before and after the infection.

In contrast to standard membrane feeding assays whereby mosquitoes are fed with cultured parasites, DMFA relies on naturally P. falciparum gametocyte-infected patients. When associated with sympatric mosquitoes, DMFA can be a reasonable approximation of what occurs in natural conditions. This requires the simultaneous availability of local mosquitoes and patients with relatively high density of gametocytes to reach sound infection rates in the mosquitoes. The parasitological surveys in the human population and the identification of gametocyte carriers can be challenging. When the opportunity of relatively high gametocytaemia arises, colony-derived mosquitoes might not always be available. In the experiments described in the current study, the availabilities of both An. gambiae and An. coluzzii were not simultaneously synchronized with that of the collected natural parasite isolates. In particular, the concentration of 0.04 g l−1 of ricinine and An. coluzzii was used for the experimental infections using parasite isolates A and E, while concentrations of 0.08 g l−1 and An. gambiae were used for other infections (isolates B–D). This means that ricinine concentration and mosquito species were here confounded.

Ricinine ingestion by mosquitoes

To confirm that ricinine was ingested by the mosquitoes used in each experiment (see below), a subset of mosquitoes fed on the sugar with the 0.04 g l−1 ricinine regime was analysed. Fifteen mosquitoes from blood-fed parasite-positive, 10 blood-fed parasite-negative and 20 blood-unfed mosquitoes were maintained on 0.04 g l−1 ricinine + 5% glucose solution and analysed. Samples consisted of five mosquitoes that were ground into 100 ml of methanol (Methanol, Fisher, Chemical) using a ball bearing to extract mosquito chemistry. These mosquito extracts (a total of nine samples: three samples of blood-fed parasite-positive, two blood-fed parasite-negative and four blood-unfed) were then analysed for the detection of ricinine, using ESIMS-LCMS, as described above.

Experiment 1: effects of ricinine on An. gambiae and An. coluzzii susceptibility to P. falciparum

The susceptibility of An. gambiae and An. coluzzii to P. falciparum was assessed in terms of both infection rate (i.e. the proportion of female mosquitoes harbouring at least one oocyst in their midgut after the infectious blood meal) and intensity (i.e. the number of oocysts per infected mosquito). To this end, a total of four parasite isolates (n = 4: isolates A–D) was used for experimental infections. On day 7/8 post-blood meal (dpbm), 160 ricinine-fed females (n = 60, 43, 27 and 30 for isolates A–D, respectively) and 164 control females (those fed on 5% glucose, n = 60, 50, 25 and 29 for isolates A–D, respectively) were dissected and stained with 1% mercurochrome to microscopically (× 400) assess the presence and number of oocysts, the immature, non-transmissible stage of the malaria parasite. Isolate A and a concentration of 0.04 g l−1 of ricinine were used to infect An. coluzzii and isolates B–D and a concentration of 0.08 g l−1 of ricinine were used to infect An. gambiae.

Experiment 2: effects of ricinine on P. falciparum oocyst rupture in mosquito midguts and sporozoite dissemination in head/thoraces

On 9–12 dpbm, a total of 170 An. coluzzii (85 fed on 0.04 g l−1 ricinine and 85 fed on 5% glucose and using parasite isolate A), 109 An. gambiae (54 fed on 0.08 g l−1 ricinine and 55 fed on 5% glucose and using isolate C) and 108 other An. gambiae (49 fed on 0.08 g l−1 ricinine and 59 fed on 5% glucose using isolate D) females were dissected daily (range: 10–31 females per day and isolate) to microscopically assess the presence and number of oocysts in mosquito midguts (isolate A) and qPCR detection of sporozoites in head/thoraces (isolates A, C, D). Anopheles gambiae females infected with isolate B were not used because they were all dissected as part of experiment 1 (see above).

Oocyst rupture in the mosquito midgut and sporozoite invasion of salivary glands are highly asynchronous. While some oocysts are intact and keep developing on 9–12 dpbm, others have already ruptured and released their sporozoites [26, 27]. To explore possible differences in the timing of sporozoite dissemination in mosquito salivary glands between ricinine-fed and control females, three metrics were measured [26, 27]:

-

(i)

The proportion of infected mosquitoes with ruptured oocysts on 10–12 dpbm; the number of mosquitoes with at least one ruptured oocyst in their midguts out of the total number of infected mosquitoes (i.e. harbouring either intact and/or ruptured oocysts).

-

(ii)

The proportion of ruptured oocysts on 10–12 dpbm; for each infected mosquito, the number of ruptured oocysts out of the total number of oocysts (intact + ruptured).

-

(iii)

The proportion of oocyst-infected mosquitoes with disseminated sporozoites in their head and thorax on 10–12 dpbm; the number of oocyst-infected mosquitoes harbouring sporozoites in their head/thoraces on 10–12 dpbm out of the total number of infected mosquitoes (i.e. harbouring either intact and/or ruptured oocysts).

Experiment 3: effects of ricinine on An. gambiae and An. coluzzii survival

To determine how parasite infection and ricinine interact to influence mosquito longevity, three membrane feeding assays were performed following the same general procedure as described above except that a group of uninfected control mosquitoes were added. Uninfected control mosquitoes received heat-treated gametocytic blood (isolates C–E) to kill parasite gametocytes, as previously described [28]. For each group (ricinine-fed and exposed to gametocytic blood, ricinine-fed and exposed to heat-treated gametocytic blood, control and exposed to gametocytic blood, and control and exposed to heat-treated gametocytic blood), between 20 and 42 females were placed in 15 × 15 × 15-cm cages. Dead mosquitoes were removed and counted in each cage (12 cages, i.e. 4 cages for each isolate C–E) every morning at 08:00. Dead mosquitoes exposed to infectious blood were individually stored in 1.5-ml tubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) at − 20 °C to determine their infection status using qPCR (see below). Isolates C, D and a concentration 0.08 g l−1 of ricinine were used to infect An. gambiae, and isolate E and a concentration of 0.04 g l−1 of ricinine were used to infect An. coluzzii.

Plasmodium falciparum DNA extraction and qPCR

Plasmodiumfalciparum genomic DNA was extracted from mosquito head-thorax by mechanical grinding tissues using Tissulyser II in an extraction buffer (0.1 M Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 0.01 M EDTA, 1.4 M NaCl, 2% cetylltrimethyl ammonium bromide) [29]. The grinding obtained was incubated at 65 °C for 10 min. Total DNA was extracted with chloroform, precipitated in isopropanol, washed in 70% ethanol and resuspended in sterile water. Parasite detection was carried out by qPCR, using P. falciparum mitochondrial DNA-specific primers 5′-TTACATCAGGAATGTTTTGC-3′ and qPCR-PfR 5′-ATATTGGGATCTCCTGCAAAT-3′ [30].

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 3.6.3) [31]. Experiment 1: logistic regression by generalized linear models (GLM) was used to test the effect of ricinine 0.04 g l−1 on the prevalence of oocysts in An. coluzzii (isolate A). We also used a binomial GLM to test the effect of ricinine 0.08 g l−1, isolates (B–D) and their interaction on the prevalence of oocysts in An. gambiae. A GLM with negative binomial errors was used to test the effect of ricinine 0.04 g l−1 on the oocyst intensity (isolate A). A negative binomial GLM was also used to test the effect of ricinine 0.08 g l−1, isolates (B–D) and their interaction on the oocyst intensity. Experiment 2: logistic regression by linear models was used to test the effect of ricinine on (i) the proportion of infected mosquitoes with ruptured oocysts (isolate A, 0.04 g l−1 ricinine) (binomial GLM), (ii) the fraction of ruptured oocysts (isolate A, 0.04 g l−1 ricinine) (quasibinomial GLM because of overdispersion) and (iii) the proportion of oocyst-infected mosquitoes with sporozoites in their head and thorax (isolates A, C and D) (binomial GLM). Experiment 3: the effect of ricinine, infection and interaction on mosquito survivorship was analysed using Cox’s proportional hazard regression model. Model simplification used stepwise removal of terms, followed by likelihood ratio tests (LRT). Term removals that significantly reduced the explanatory power (P < 0.05) were retained in the minimal adequate model [32]. R scripts and raw datasets are described in Additional files 1, 2, 3, 4.

Results

Ingestion of ricinine by mosquitoes

Mosquitoes experimentally administered ricinine from all three feeding groups (blood-fed parasite positive, blood-fed parasite negative and blood-unfed) were found to have a detectable amount of ricinine using ESIMS-LCMS analysis. Of the nine samples analysed, two of the three blood-fed parasite-positive samples, both of the blood-fed parasite-negative samples and all of the four blood-unfed samples had detectable levels of ricinine, ranging from 1 to 10 µM.

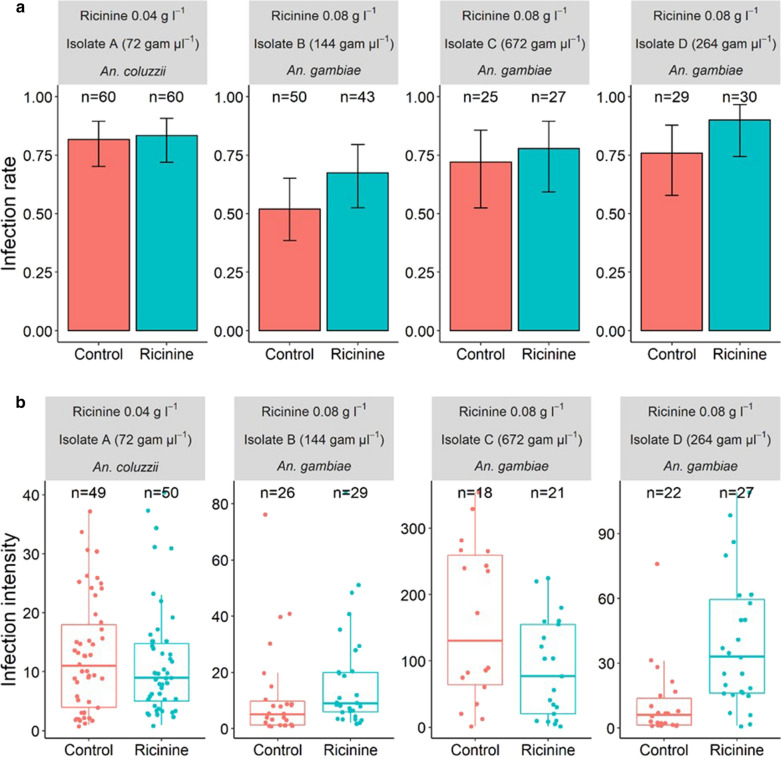

Experiment 1: effects of ricinine on An. gambiae and An. coluzzii susceptibility to P. falciparum

At a concentration of 0.04 g l−1, ricinine had no effect on An. coluzzii infection rate (LRT X2 = 0.06, df = 1, P = 0.81, Fig. 1a, left panel) or intensity (LRT X2 = 0.5, df = 1, P = 0.48, Fig. 1b, left panel). However, at a concentration of 0.08 g l−1, ricinine increased the overall infection rate of An. gambiae by 14% (parasite isolates B–D, Fig. 1a, LRT X2 = 4.5, df = 1, P = 0.03). This increase was consistent across all three parasite isolates used to infect the mosquitoes, i.e. no isolate by treatment interaction was observed (LRT X2 = 0.58, df = 2, P = 0.75). The effect of the higher concentration of ricinine (0.08 g l−1) on infection intensity, however, differed across parasite isolates, i.e. a significant isolate by treatment interaction was observed (LRT X2 = 16.51, df = 2, P = 0.0003, Fig. 1b). While 0.08 g l−1 ricinine increased the number of developing parasites in mosquitoes exposed to isolates B and D, mosquitoes exposed to isolate C tended to have a decreased number of parasites (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Effect of ricinine on the susceptibility of Anopheles gambiae and An. coluzzii to four natural isolates of Plasmodium falciparum (A, B, C and D). a Infection rate (± 95% CI) on day 7 post-blood meal (dpbm), expressed as the number of females harbouring at least one oocyst in their midguts out of the total number of dissected females for each treatment (red bars: control mosquitoes fed with a 5% glucose solution; blue bars: test mosquitoes fed with a 5% glucose solution and either 0.04 or 0.08 g l−1 of ricinine) and for each of four parasite isolates (A–D). b Infection intensity at 7 dpbm, expressed as the number of developing oocysts in midguts of infected females, for each treatment and the four parasite isolates. A concentration of 0.04 g l−1 of ricinine and An. coluzzii were used for the first experimental infection using parasite isolate A (left panel in a and b), while concentrations of 0.08 g l−1 and An. gambiae were used for other infections (isolates B, C and D). “g µl−1” corresponds to the number of gametocytes per microlitre of blood

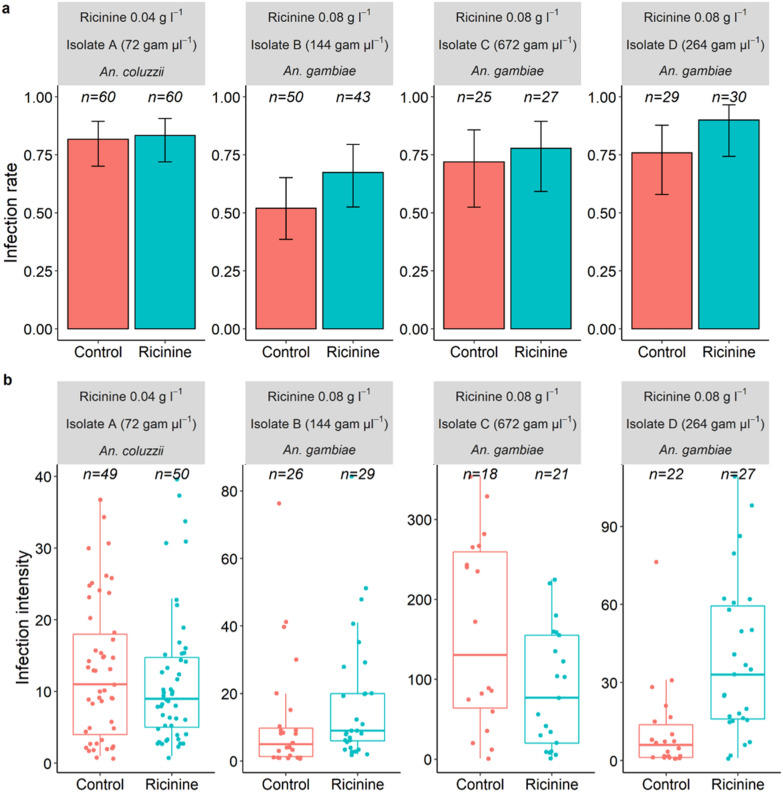

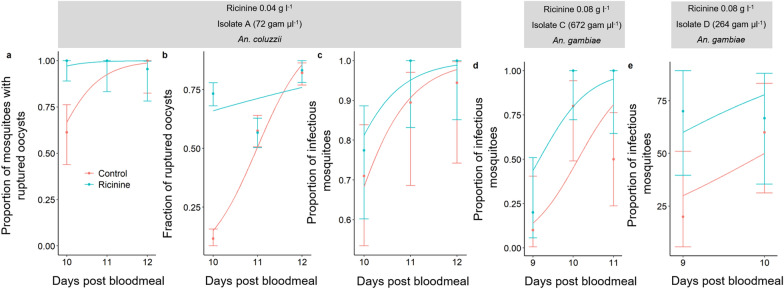

Experiment 2: effect of ricinine on P. falciparum oocyst rupture in mosquito midguts and sporozoite dissemination in heads/thoraces

A total of 140 An. coluzzii females (72 fed on 0.04 g l−1 of ricinine and 68 on control diet) exposed to parasite isolate A were dissected daily from 9 to 12 dpbm (between 18 and 31 females/day/treatment) to microscopically assess the presence and number of oocysts (intact and ruptured) in the mosquito midguts and for the qPCR detection of sporozoites in head/thorax. Ricinine increased the proportion of mosquitoes with ruptured oocysts (LRT X2 = 12.8, df = 1, P = 0.0003, Fig. 2a): all mosquitoes (100%) from the ricinine treatment exhibited at least one ruptured oocyst in their midgut by 10 dpbm compared to 61% in the control group (Fig. 2a). In addition, the fraction of ruptured oocysts in mosquito midguts was higher in the ricinine treatment than in the control (LRT X2 = 109, df = 1, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2b). Finally, the proportion of mosquitoes with disseminated sporozoites in their head/thorax, the most epidemiologically relevant metric, was higher in ricinine-fed mosquitoes compared to controls from 9 to 12 dpbm (LRT X2 = 18.9, df = 1, P < 0.0001, Fig. 1c–e), regardless of the parasite isolate, i.e. no treatment by isolate interaction (LRT X2 = 1.2, df = 2, P = 0.55). Moreover, sporozoite dissemination in the head/thorax of ricinine-fed mosquitoes occurred earlier than in control (significant dpbm by treatment interaction: LRT X2 = 4.36, df = 1, P = 0.037, Fig. 2c, d). Together, these results suggest that ricinine increased the maturation of P. falciparum.

Fig. 2.

Effect of ricinine on Plasmodium falciparum oocyst rupture in mosquito midguts and sporozoite dissemination in head/thoraces for three parasite isolates (A, C and D). a Proportion of infected mosquitoes with ruptured oocysts (± 95% CI) from 10 to 12 dpbm, expressed as the number of mosquitoes with at least one ruptured oocyst out of the total number of infected mosquitoes, i.e. harbouring either intact and/or ruptured oocysts, in response to the ricinine treatment (blue) or the control (red). The lines represent best-fit logistic growth curves for each treatment. b Fraction of ruptured oocysts (± 95% CI), expressed as the number of ruptured oocysts out of the total number of oocysts (intact + ruptured). The lines represent best-fit logistic growth curves for each isolate. c Proportion of mosquitoes with disseminated sporozoites in the head/thorax (± 95% CI). Sample size = 7–31 individuals/dpbm/isolate/treatment (mean = 14.75). A concentration of 0.04 g l−1 of ricinine and Anopheles coluzzii was used for the first experimental infection using parasite isolate A (panels a–c), while concentrations of 0.08 g l−1 and An. gambiae were used for other infections (isolates C and D)

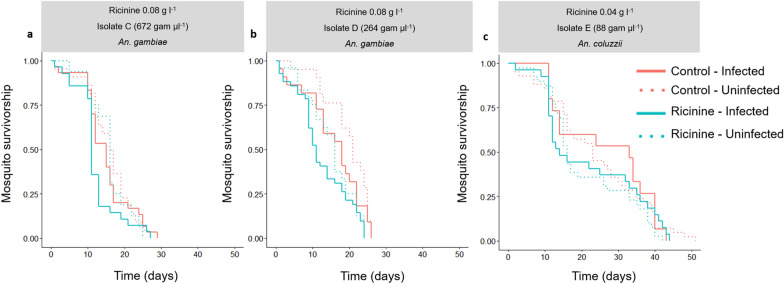

Experiment 3: effects of ricinine on An. gambiae and An. coluzzii survival

The survival of (i) ricinine-fed mosquitoes exposed to P. falciparum (n = 106); (ii) ricinine fed and unexposed, i.e. received a heat-treated gametocytic blood meal (n = 97), mosquitoes; (iii) glucose-fed control mosquitoes and females exposed to P. falciparum (n = 103) and (iv) glucose-fed control and unexposed (n = 86) mosquitoes were monitored from 1 to 50 dpbm, when the last mosquito died. The DNA of P. falciparum-exposed dead mosquitoes was extracted to detect the presence of P. falciparum using qPCR. Mosquitoes (ricinine-fed or glucose-fed control), which remained uninfected upon parasite exposure, were excluded from the analysis to focus on the effect of infection and ricinine (0.04 g l−1 and 0.08 g l−1) on mosquito survival. Ricinine exerted a toxic effect, reducing mosquito median survival by 3.5 days (n = 152 5% glucose control females and 176 ricinine-fed females, LRT X2 = 10.7, df = 1, P = 0.001, hazard ratio = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.09–1.69, Fig. 3). This was true regardless of the mosquito infection status (interaction between infection and treatment: LRT X2 = 0.005, df = 2, P = 0.94, Fig. 3) and parasite isolate (interaction between isolate and treatment: LRT X2 = 0.7, df = 2, P = 0.7, Fig. 3). Mosquito survival was not influenced by infection (LRT X2 = 0.64, df = 1, P = 0.42) and there was no infection by isolate interaction (LRT X2 = 4.5, df = 2, P = 0.1). An. coluzzii used for isolate E lived longer than An. gambiae used for isolates C and D (LRT X2 = 65.6, df = 2, P < 0.001). Finally, there was no three-way interaction among treatment, infection and isolate (LRT X2 = 0.88, df = 2, P = 0.64).

Fig. 3.

Effect of ricinine on the longevity of uninfected and Plasmodium falciparum-infected Anopheles gambiae and An. coluzzii using three parasite isolates (C, D and E). A concentration of 0.08 g l−1 of ricinine was used to test its effect on the survival of An. gambiae exposed to isolates C and D (a, b), while a concentration of 0.04 g l−1 was used to test its effect on the longevity of An. coluzzii exposed to isolate E (c). Mosquitoes were monitored until all individuals died. Sample size = 16–42 individuals/treatment/infection/isolate (mean = 34)

Discussion

In this study, laboratory assays were conducted to evaluate the impact of the alkaloid ricinine on the (i) survival and (ii) susceptibility of female An. gambiae and An. coluzzii to natural isolates of P. falciparum as well as (iii) the parasite growth rate. Overall, our results demonstrated that the consumption of ricinine in glucose solution decreased the lifespan of both An. gambiae and An. coluzzii, increased An. gambiae susceptibility to infection at a concentration of 0.08 g l−1 and accelerated parasite development in both mosquito species.

Although secondary metabolites contained in plant nectars function primarily as a defence against herbivores, there can be a variety of potential benefits and costs for nectar feeders to acquire these phytochemicals [33]. In particular, secondary compounds, including phenolic acids and flavonols, may enhance insect longevity [34], plant attractiveness to pollinators [35] or protection against pathogens [36, 37]. However, the role of alkaloid secondary compounds in insect-plant interactions remains elusive. Some alkaloids can be beneficial, e.g. enhance honeybee memory formation through odour cues associated with food rewards [38]. However, consumption of alkaloids is generally costly in that they reduce insect survival and fecundity [39]. Consistent with previous studies on Anopheles mosquitoes [19, 20], we found that mosquitoes fed with 0.04 g l−1 or 0.08 g l−1 of the alkaloid ricinine and 5% glucose solution displayed reduced survival compared to controls. Nyasembe et al. [20] observed that 50% of An. gambiae fed a 0.04 g l−1 ricinine in a 6% glucose solution were dead within 4 days, while here we report a median survival time of 12 days in ricinine-fed An. gambiae and An. coluzzii. A possible explanation for the observed discrepancy could be the status of insecticide resistance in the mosquito colonies used in this study. The outbred An. gambiae and An. coluzzii colonies are derived from females collected recently in the villages of Soumousso and Bama, respectively, where the level of phenotypic insecticide resistance is found to be highly associated to elevated activity of enzymes of detoxification [40]. A high level of metabolic resistance to insecticides could concomitantly be associated with an enhanced ability to detoxify plant secondary metabolites [41]. Future studies exploring the effect of ricinine and other plant secondary compounds on the survival of insecticide resistant vs. susceptible individuals will be required to confirm this possibility in mosquitoes.

The transmission potential of Plasmodium parasites by Anopheles vectors is extremely sensitive to variation in mosquito survival [41, 42]. Small changes in mosquito lifespan can result in relatively large changes in transmission potential [41, 42]. As such, ricinine delivered through attractive sugar baits in field settings could result in decreased malaria transmission. On the other hand, our data indicate that oocyst rupturing and sporozoite invasion of mosquito salivary glands occur earlier in ricinine-fed mosquitoes, suggesting that ricinine actually facilitates growth acceleration of P. falciparum within the mosquito gut. The transmission of P. falciparum is also sensitive to variation in the extrinsic incubation period (EIP) of the parasite, in which a shortened EIP inevitably results in an earlier development of infection in the mosquitoes and thereby a higher risk of transmission. While the mechanism underlying the ricinine-enhanced developmental rate of P. falciparum is unknown, ricinine may exert a direct effect on the Plasmodium parasites, through stimulation of DNA replication and/or ATP production. The shortened EIP and decreased mosquito lifespan induced by ricinine may have a contrasting effect on malaria transmission. These results would need to be combined into an epidemiological model to predict the contribution of ricinine to overall malaria transmission potential.

Shorter EIP in ricinine-fed mosquitoes could illustrate a case of adaptive phenotypic plasticity in response to decreased mosquito survival, which reduces future opportunities of transmission. However, it is currently unclear whether malaria parasites can accelerate their sporogonic cycle when their transmission is compromised by the imminent death of their mosquito vector [44]. Such condition-dependent developmental strategies, described in blood-stage malaria parasites [44, 45], deserve consideration in infected mosquitoes.

Anti-parasite effects of nectar alkaloids have been demonstrated in bumblebees [14, 46]. In particular, the consumption of the alkaloids anabasine, nicotine and gelsemine significantly reduced the load of Crithidia bombi, a protozoan parasite of bumblebees by 81, 61 and 100%, respectively [14, 46]. In the present study, at a concentration of 0.04 g l−1, ricinine had no effect on An. coluzzii infection. At a concentration of 0.08 g l−1, our findings indicate a 14% increase in An. gambiae infection rate. Similarly, ricinine tended to increase the infection load of An. gambiae, although this effect was inconsistent across the parasite isolates used. The precise mechanisms behind this effect are not yet clear but interactions among mosquito detoxification of ricinine, body condition and immune responses can be suspected. In particular, Anopheles mosquitoes could be subject to a trade-off between immune response and survival such that when they are maintained on a ricinine-glucose solution, they allocate more energy to detoxification, to retrieve lifespan perspective, at the cost of immune response. If this hypothesis is correct, we would also expect fecundity reduction in ricinine-fed mosquitoes.

Eight of the nine mosquito samples analysed had detectable levels of ricinine, ranging from 1 to 10 µM. This indicates that ricinine was ingested concurrently with sugar feeding, which is consistent with the observation of Nyasembe et al. [20], who detected ricinine in mosquito midguts after feeding on dosed sugar solutions. Future studies are required to quantify the level of sugar intake by control mosquitoes and ricinine-fed mosquitoes. Because of its bitter taste, it is possible that sugar intake (amount and frequency) in treated mosquitoes was reduced and resulted in undernourished, poorly vigorous mosquitoes. This could also explain the increased infection level and decreased longevity observed in these mosquitoes.

Examples of an increase in infection following the ingestion of a toxic molecule by an insect are scarce in the literature. The results reported here are comparable to those obtained by Terzian et al. [48] wherein the oocyst density of P. gallinaceum varied in a dose-dependent manner in the gut of Ae. aegypti maintained on sulfadiazine- or PABA-4% sugar solutions. This relationship was characterized by a low-dose stimulation of PABA or sulfadiazine and a high-dose inhibition resulting in an inverted U-shaped dose response, similar to hormesis. Repeating experiment 1 using a higher dose of ricinine would allow confirming this possibility. To maximize the success of mosquito feeding success, females were here starved of sugar solution for 24 h before receiving the infectious blood meal. During this 24-h period it is possible that ricinine concentration in the mosquito tissues dropped to a level ineffective on the early phases of parasite development. Future experiments, suppressing or reducing the mosquito starvation period, would be required to possibly reach higher concentrations of ricinine in the guts when the early and most fragile stages of the parasite begin the sporogonic cycle.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings reveal that the consumption of the nectar alkaloid ricinine can have unsuspected and contrasting effects on key phenotypic traits that govern the intensity of malaria transmission. Future work is needed before concluding on the possible role of ricinine as a novel control agent, including the development of ricinine-based toxic and transmission-blocking sugar baits. Testing other secondary phytochemicals in plant nectar will provide a broader understanding of plant-mediated effects on the transmission of vector-borne diseases.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Data for experiment 1 used for Fig.1 and statistical analyses.

Additional file 2. Data for experiment 2 used for Fig.2 and statistical analyses.

Additional file 3. Data for experiment 3 used for Fig.3 and statistical analyses.

Additional file 4. Rscript used for all Figures and statistical analyses.

Acknowledgements

We thank all volunteers for participating in this study as well as the local authorities for their support. We are very grateful to all the students and technicians at the IRSS/IRD who provided valuable assistance for the experiments of this study.

Abbreviations

- dpbm

Days post-blood meal

- L:D

Light dark

- qPCR

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

- DMFA

Direct membrane feeding assay

Authors’ contributions

DFDSH, PSLP, AC, PS, TL conceived and designed the study. DFDSH, PSLP, AC, BK, EG, BKY, IWF conducted the experiments. DFDSH, PSLP, AC and TL analysed the data. DFDSH, PSLP and TL drafted the manuscript. SY, TL, JBO, OG, AC and KRD supervised the study. All authors read, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the ANR Grant No. 16-CE35-0007, the Swedish Research Council Grant No. 2019-03732 and JEAI Grant No. AAP2018_JEAI_PALUNEC.

Availability of data and materials

All data and R code files are included within the article’s additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol was approved by the Centre Muraz and IRSS ethics committees: A003-2012/CE-CM and 2017-003/MESRSI/CNRST/IRSS/CEIRES. Prior to inclusion, informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardian of the volunteers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We declare that no competing interests existed for the authors or the institutes before, during and after preparing and submitting this paper for review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO . World malaria report. Geneva: WHO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feachem RGA, Chen I, Akbari O, Bertozzi-Villa A, Bhatt S, Binka F, et al. Malaria eradication within a generation: ambitious, achievable, and necessary. Lancet. 2019;394:1056–1112. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinden RE. Developing transmission-blocking strategies for malaria control. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006336. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delves MJ, Angrisano F, Blagborough AM. Antimalarial transmission-blocking interventions: past, present, and future. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:735–746. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira TN, Pita-Pereira D, Costa SG, Brazil RP, Moraes CS, Díaz-Albiter HM, et al. Transmission blocking sugar baits for the control of Leishmania development inside sand flies using environmentally friendly beta-glycosides and their aglycones. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:614. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3122-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paaijmans K, Fernàndez-Busquets X. Antimalarial drug delivery to the mosquito: an option worth exploring? Future Microbiol. 2014;9:579–582. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delves M, Lafuente-Monasterio MJ, Upton L, Ruecker A, Leroy D, Gamo FJ, et al. Fueling open innovation for malaria transmission-blocking drugs: hundreds of molecules targeting early parasite mosquito stages. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2134. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paton DG, Childs LM, Itoe MA, Holmdahl IE, Buckee CO, Catteruccia F. Exposing Anopheles mosquitoes to antimalarials blocks Plasmodium parasite transmission. Nature. 2019;567:239–243. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0973-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster WA. Mosquito sugar feeding and reproductive energetics. Annu Rev Entomol. 1995;40:443–474. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.40.010195.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chris MS, Woodbridge AFV. Plant-sugar feeding and vectorial capacity. Ecol Parasite Vector Interact. 2013 doi: 10.3920/978-90-8686-744-8_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peach DAH, Gries G. Mosquito phytophagy—sources exploited, ecological function, and evolutionary transition to haematophagy. Entomol Exp Appl. 2020;168:120–136. doi: 10.1111/eea.12852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butcher G. Antimalarial drugs and the mosquito transmission of Plasmodium. Int J Parasitol. 1997;27:975–987. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(97)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerberg EJ. Evaluation of antimalarial compounds in mosquito test systems. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1971;65:358–363. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(71)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson LL, Adler LS, Leonard AS, Andicoechea J, Regan KH, Anthony WE, et al. Secondary metabolites in floral nectar reduce parasite infections in bumble bees. Proc R Soc B. 2015;282:2014–2471. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson PC, Nicolson SW, Wright GA. Plant secondary metabolites in nectar: impacts on pollinators and ecological functions. Funct Ecol. 2017;31:65–75. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moyo P, Mugumbate G, Eloff JN, Louw AI, Maharaj VJ, Birkholtz LM. Natural products: a potential source of malaria transmission blocking drugs? Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13:251. doi: 10.3390/ph13090251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yerbanga RS, Lucantoni L, Ouédraogo RK, Da DF, Yao FA, Yaméogo KB, et al. Transmission blocking activity of Azadirachta indica and Guiera senegalensis extracts on the sporogonic development of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates in Anopheles coluzzii mosquitoes. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:185. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hien DFDS, Dabiré KR, Roche B, Diabaté A, Yerbanga RS, Cohuet A, et al. Plant-mediated effects on mosquito capacity to transmit human malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005773. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wachira SW, Omar S, Jacob JW, Wahome M, Alborn HT, Spring DR, et al. Toxicity of six plant extracts and two pyridone alkaloids from Ricinus communis against the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:312. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyasembe VO, Cheseto X, Kaplan F, Foster WA, Teal PEA, Tumlinson JH, et al. The invasive American weed Parthenium hysterophorus can negatively impact malaria control in Africa. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdul WM, Hajrah NH, Sabir JSM, Al-garni SM, Sabir MJ, Kabli SA, et al. Therapeutic role of Ricinuscommunis L. and its bioactive compounds in disease prevention and treatment. Asian Pacific J Trop Med. 2018;11:177–85. doi: 10.4103/1995-7645.228431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel K, Patel DK. Medicinal significance, pharmacological activities, and analytical aspects of ricinine: a concise report. J Coast Life Med. 2016;4:663–667. doi: 10.12980/jclm.4.2016J6-96. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jumba BN, Anjili CO, Judith M, Ingonga J, Nyamao R, Marango S, et al. Evaluation of leishmanicidal activity and cytotoxicity of Ricinus communis and Azadirachta indica extracts from western Kenya: in vitro and in vivo assays. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:650. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1605-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holfelder MGAH, Steck M, Komor E, Seifert K. Ricinine in phloem sap of Ricinus communis. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:1461–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00773-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Souza KMR, Guilhon GMSP, Santos LS, Cascaes MM, Secco RS, Brasil DSB, et al. Ricinine and other constituents of Aparisthmium cordatum (Euphorbiaceae) Nat Prod Res. 2013;27:364–370. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2012.695368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guissou E, Waite J, Jones M, Bell A, Suh E, Yameogo K, et al. Using a non-destructive sugar-feeding assay for sporozoite detection and estimating the extrinsic incubation period of Plasmodium falciparum in mosquito vectors. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9344. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88659-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guissou E, Poda S, De Sales Hien DF, Yerbanga SR, Da DF, Cohuet A, et al. Effect of irradiation on the survival and susceptibility of female Anopheles arabiensis to natural isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:266. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04135-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sangare I, Michalakis Y, Yameogo B, Dabire R, Morlais I, Cohuet A. Studying fitness cost of Plasmodium falciparum infection in malaria vectors: validation of an appropriate negative control. Malar J. 2013;12:2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morlais I, Ponçon N, Simard F, Cohuet A, Fontenille D. Intraspecific nucleotide variation in Anopheles gambiae: new insights into the biology of malaria vectors. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:795–802. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2004.71.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boissière A, Gimonneau G, Tchioffo MT, Abate L, Bayibeki A, Awono-Ambéné PH, et al. Application of a qPCR assay in the investigation of susceptibility to malaria infection of the M and S molecular forms of An.gambiae s.s. in Cameroon. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Team R core . A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Vienna: R-project; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crawley MJ. The R book. 2. Chichester: Wiley; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevenson PC. For antagonists and mutualists: the paradox of insect toxic secondary metabolites in nectar and pollen. Phytochem Rev. 2020;19:603–614. doi: 10.1007/s11101-019-09642-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liao LH, Wu WY, Berenbaum MR. Impacts of dietary phytochemicals in the presence and absence of pesticides on longevity of honey bees (Apis mellifera) Insects. 2017;8:22. doi: 10.3390/insects8010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afik O, Dag A, Shafir S. The effect of avocado (Persea americana) nectar composition on its attractiveness to honey bees (Apis mellifera) Apidologie. 2006;37:317–325. doi: 10.1051/apido:2005064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernklau E, Bjostad L, Hogeboom A, Carlisle A, Arathi HS. Dietary phytochemicals, honey bee longevity and pathogen tolerance. Insects. 2019;10:14. doi: 10.3390/insects10010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koch H, Woodward J, Langat MK, Brown MJF, Stevenson PC. Flagellum removal by a nectar metabolite inhibits infectivity of a bumblebee parasite. Curr Biol. 2019;29:3494–3500. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright GA, Baker DD, Palmer MJ, Stabler D, Mustard JA, Power EF, et al. Caffeine in floral nectar enhances a pollinator’s memory of reward. Science. 2013;339:1202–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.1228806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chowański S, Adamski Z, Marciniak P, Rosiński G, Büyükgüzel E, Büyükgüzel K, et al. A review of bioinsecticidal activity of solanaceae alkaloids. Toxins. 2016;8:60. doi: 10.3390/toxins8030060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Namountougou M, Soma DD, Kientega M, Balboné M, Kaboré DPA, Drabo SF, et al. Insecticide resistance mechanisms in Anopheles gambiae complex populations from Burkina Faso, West Africa. Acta Trop. 2019;197:105054. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bagchi VA, Siegel JP, Demkovich MR, Zehr LN, Berenbaum MR. Impact of pesticide resistance on toxicity and tolerance of host plant phytochemicals in amyelois transitella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) J Insect Sci. 2016;16:62. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iew063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith DL, McKenzie FE. Statics and dynamics of malaria infection in Anopheles mosquitoes. Malar J. 2004;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brady OJ, Godfray HCJ, Tatem AJ, Gething PW, Cohen JM, Ellis McKenzie F, et al. Vectorial capacity and vector control: reconsidering sensitivity to parameters for malaria elimination. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2016;110:107–117. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lefevre T, Ohm J, Dabiré KR, Cohuet A, Choisy M, Thomas MB, et al. Transmission traits of malaria parasites within the mosquito: genetic variation, phenotypic plasticity, and consequences for control. Evol Appl. 2018;11:456–469. doi: 10.1111/eva.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mideo N, Reece SE. Plasticity in parasite phenotypes: evolutionary and ecological implications for disease. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:17–24. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saliba KS, Jacobs-Lorena M. Production of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in vitro. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;923:17–25. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-026-7_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manson JS, Otterstatter MC, Thomson JD. Consumption of a nectar alkaloid reduces pathogen load in bumble bees. Oecologia. 2010;162:81–89. doi: 10.1007/s00442-009-1431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terzian LA, Stahler N, Ward PA. The effect of antibiotics and metabolites on the immunity of mosquitoes to malarial infection. J Infect Dis. 1952;90:116–130. doi: 10.1093/infdis/90.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Data for experiment 1 used for Fig.1 and statistical analyses.

Additional file 2. Data for experiment 2 used for Fig.2 and statistical analyses.

Additional file 3. Data for experiment 3 used for Fig.3 and statistical analyses.

Additional file 4. Rscript used for all Figures and statistical analyses.

Data Availability Statement

All data and R code files are included within the article’s additional files.