Abstract

From December 1997 to March 1998, 25 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates exhibiting negative Staphylase (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, England) reactions were identified from various clinical specimens from 13 patients in six intensive care units (ICUs) or in wards following a stay in an ICU at the National Taiwan University Hospital. The characteristics of these isolates have not been previously noted in other MRSA isolates from this hospital. Colonies of all these isolates were grown on Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood and were nonhemolytic and unpigmented. Seven isolates, initially reported as Staphylococcus haemolyticus (5 isolates) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (2 isolates) by the routine identification scheme and with the Vitek GPI system (bioMerieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.), were subsequently identified as S. aureus by positive tube coagulase tests, standard biochemical reactions, and characteristic cellular fatty acid chromatograms. The antibiotypes obtained by the E test, coagulase types, restriction fragment length polymorphism profiles of the staphylococcal coagulase gene, and random amplified polymorphic DNA patterns generated by arbitrarily primed PCR of the isolates disclosed that two major clones disseminated in the ICUs. Clone 1 (16 isolates) was resistant to clindamycin and was susceptible to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) and was coagulase type II. Clone 2 (eight isolates) was resistant to clindamycin and TMP-SMZ and was coagulase type IV. These two epidemic clones from ICUs are unique and underline the need for caution in identifying MRSA strains with colonial morphologies not of the typical type and with negative Staphylase reactions.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a common cause of nosocomial infections in hospitalized patients, particularly in those who remain in intensive care units (ICUs) for extended periods of time (10, 16). Control of the dissemination of MRSA in hospitals relies on the timely identification of these organisms and then the early institution of appropriate infection control measures (6, 15, 16). Prompt and accurate identification of the species of Staphylococcus involved is crucial because the control method implemented varies depending on the identity of the epidemic strain(s) (10, 15, 16).

Various commercially produced kits for the identification of S. aureus are widely used in the clinical microbiology laboratory (10). Although the tube coagulase test with rabbit plasma for the detection of free coagulase is generally considered the “gold standard” for the identification of S. aureus, the time-consuming nature of the test (4 to 24 h is required) makes the rapid slide coagulase tests, including the latex agglutination and hemagglutination methods for the detection of the presence of clumping factors or protein A, more attractive alternatives (1, 4, 12–14, 19, 23, 24). Unfortunately, the major drawback of some of the commercial kits is their inability to accurately detect MRSA, with false-negative rates being as high as 25% (19, 20).

From December 1997 to March 1998, we collected 25 isolates of MRSA exhibiting negative Staphylase (Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, England) reactions. The isolates were recovered from 13 patients in six ICUs or in wards following a stay on an ICU. The antibiotypes, cellular fatty acid chromatograms, coagulase types, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) profiles of the staphylococcal coagulase gene, and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) patterns generated by arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) were obtained to determine the microbiological characteristics and epidemiological relatedness of these isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

From December 1997 to March 1998, 747 isolates of MRSA were recovered from various clinical specimens from patients who were treated at National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH), a 2,000-bed teaching hospital in northern Taiwan. Among these isolates, 25 were negative for the Staphylase reaction on at least two occasions. The results of the Staphylase reaction were read within 20 s. These organisms were identified as S. aureus by standard microbiological methods as described previously (10). On some occasions, species identification with the Vitek GPI system (bioMerieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.) was performed when gram-positive cocci which consisted of nonhemolytic and cream-white colonies and which had positive catalase and negative Staphylase reactions were found. Methicillin resistance was identified by the standard disk (oxacillin disk) diffusion method according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines (18).

Surveillance of the outbreak.

Surveillance cultures of various clinical specimens from all patients who resided in the six ICUs and cultures of hand and nasal swab specimens from medical personnel started in early January 1998. However, none of the cultures from any of the patients were positive for slide coagulase-negative MRSA.

Cellular fatty acid analysis.

Bacterial cell harvest and lysis, saponification, methylation of fatty acids, and extraction and analysis of fatty acid methyl esters were carried out with the Microbial Identification System (MIS; Microbial ID Inc., Newark, Del.) as described previously (9). The similarity index (range, 0 to 1) was defined as the closeness of a match of the unknown bacterium to a library entry. A similarity index of >0.6 was defined as an excellent match.

Antibiotype.

Susceptibility testing of the 25 MRSA isolates was performed by the E test (PDM Epsilometer; AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The antimicrobial agents, which were tested at concentrations ranging from 0.016 to 256 μg/ml, included oxacillin, cefazolin, erythromycin, clarithromycin, gentamicin, and vancomycin. The concentrations of teicoplanin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ), and quinupristin-dalfopristin ranged from 0.016 to 32 μg/ml. S. aureus ATCC 29213 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 were used as control strains in each set of tests.

MIC breakpoints for defining susceptibilities were in accordance with the 1998 NCCLS criteria (18). The antibiotypes of the isolates were considered to be different if the discrepancies in the MICs of at least one of the antimicrobial agents tested were ≥2 dilutions; otherwise, they were considered identical (7). To define the discrepancies in the MICs, any MIC of ≥256 μg/ml was considered 512 μg/ml.

Coagulase type.

Coagulase types were determined by the neutralization test with antisera against each of the different coagulase types (types I to VII; Denka Seiken Inc., Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Three clinical isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci (one each of S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus, and S. saprophyticus) were typed as negative controls, and S. aureus ATCC 29213 was typed as a positive control.

RAPD patterns.

The method used to extract chromosomal DNA and the PCR conditions used for determination of the RAPD patterns generated by AP-PCR of the isolates were as described previously (8). Two arbitrary oligonucleotide primers (M13 [5′-GAGGGTGGCGGTTCT-3′; Gibco BRL Products, Gaithersburg, Md.] and H12 [5′-ACGCGCATGT-3′; OPERON Technologies, Inc., Alameda, Calif]) were used. The AP-PCR analyses of these isolates were performed in duplicate. Interpretation of the RAPD patterns followed the previous description (7, 8). In addition to the 25 MRSA isolates with negative Staphylase reactions, the RAPD patterns of 10 MRSA strains that were isolated from the ICUs during the same study period and that had positive Staphylase reactions were also determined.

PCR amplification and restriction analysis of staphylococcal coagulase gene.

The 3′ end region of the coagulase gene containing the 81-bp tandem repeats was amplified with two primers (COAG 2 [5′-CGAGACCAAGATTCAACAAG-3′] and COAG 3 [5′-AAAGAAAACCACTCACATCA-3′]) (5, 6). Analysis of the RFLPs of the amplicons was determined by digestion with AluI (5, 6). The three coagulase-negative staphylococci used in the coagulase typing study were also analyzed as negative controls.

Clonality.

Isolates that shared identical patterns by RAPD analysis with the two primers, that had identical antibiotypes, and whose RFLP profiles of the staphylococcal coagulase gene were identical were considered to belong to a single clone.

RESULTS

Characterizations of patients harboring MRSA strains with negative Staphylase reactions.

Table 1 presents the demographic data and clinical features of the 13 patients and the microbiological characteristics of the 25 MRSA isolates with negative Staphylase reactions. All these isolates were recovered from various specimens while the patients were staying in the ICUs or within 3 days after the patients were moved to medical wards (patients 8 and 12). Among these patients, six had bacteremia, two had catheter-associated infections, and two had ventilator-related pneumonia. These patients resided in six separate ICUs; the majority of units were located in the third floor of the three parts (parts A, B, and C) of the NTUH building.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 25 isolates of Staphylase reaction-negative S. aureus and MRSA

| Patient no. | Age (yr)/sexa | Type of infection | Wardb | Isolate

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen | Designation | Date of isolation (day/mo/yr) | Coagulase type | Antibiotype | Fatty acid chromatogram profile | Coagulase gene RFLP pattern | RAPD patternc | ||||

| 1 | 81/M | Bacteremia | 3B2 | Sputum | A1 | 8/12/1997 | II | A | A | 1 | a |

| Blood | A2 | 18/12/1997 | II | A | A | 1 | a | ||||

| 2 | 33/M | Bacteremia | 3B2 | Blood | B1 | 2/1/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a |

| Empyema thoracis | Sputum | B2 | 9/2/1998 | II | B | A | 1 | b | |||

| Empyema thoracis | Empyema | B3 | 9/2/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a | |||

| 3 | 68/M | Bacteremia | 3B2 | Blood | C1 | 16/1/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a |

| Catheter-related infection | CVCd tip | C2 | 7/2/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a | |||

| 4 | 1/M | Catheter-related infection | 5F1 | CVC tip | D1 | 3/2/1998 | IV | C | B | 2 | c |

| Catheter-related infection | Wound (CVC) | D2 | 4/2/1998 | IV | C | B | 2 | c | |||

| Wound infection (right ankle) | Wound | D3 | 4/2/1998 | IV | C | B | 2 | c | |||

| 5 | 50/M | Burn | 3A2 | Wound (leg) | E1 | 7/1/1998 | IV | C | B | 2 | c |

| Burn | Wound (hand) | E2 | 4/2/1998 | IV | C | B | 2 | c | |||

| 6 | 68/M | Bacteremia | 3C2 | Blood | F1 | 26/1/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a |

| Bacteremia | Blood | F2 | 26/1/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a | |||

| Bacteremia | Stool | F3 | 5/2/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a | |||

| Catheter-related infection | CVC tip | F4 | 19/2/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a | |||

| 7 | 84/M | Ventilator-related pneumonia | 3B2 | Sputum | G1 | 2/2/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a |

| Sputum | G2 | 6/2/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a | ||||

| 8 | 39/F | Ventilator-related pneumonia | 3B2 | Sputum | H | 19/2/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a |

| 9 | 62/F | Burn | 3A1 | Wound (leg) | I | 9/3/1998 | IV | C | B | 2 | c |

| 10 | 38/M | Bacteremia | 3C1 | Blood | J | 10/2/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a |

| 11 | 76/F | Bacteremia | 3C1 | Blood | K | 2/2/1998 | IV | C | B | 2 | c |

| 12 | 78/M | Pneumonia | 3B2 | Sputum | L | 10/3/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a |

| 13 | 69/F | Perforated peptic ulcer | 3B2 | Wound | M1 | 9/2/1998 | II | A | A | 1 | a |

| Tracheobronchitis | Sputum | M2 | 23/2/1998 | IV | C | B | 2 | c | |||

M, male; F, female.

The first number indicates the floor of the NTUH building; A to D indicate different parts of the building; 3A1, 3B2, 3C1, and 3C2 are ICUs and 5FI is a neonatal ICU.

RAPD patterns generated with primer, M13 and H12.

CVC, central veinous catheter.

Bacterial isolates.

Among the 25 isolates which were noted to be unreactive by the Staphylase test, 7 were initially identified and were reported to be S. haemolyticus (isolates A1, B1, D1, E1, and F2) or S. epidermidis (isolates C1 and G2) with the Vitek GPI card (if the results of the catalase and coagulase reactions were marked in the appropriate oval depressions in the card). All these isolates were subsequently identified as S. aureus on the basis of positive catalase and nuclease activities, growth on mannitol salt agar, resistance to bacitracin (0.04-U disk) and polymyxin (300-U disk) but susceptibility to novobiocin (5-μg disk), and a positive tube coagulase test result (the results were read at 4 and 24 h) (10). Colonies on the Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood were nonhemolytic, unpigmented or cream-white in color, and 5 to 6 mm in diameter with an entire edge within 24 or 48 h of incubation in ambient air at 35°C. All isolates were resistant to oxacillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, and gentamicin and were susceptible to minocycline, vancomycin, and teicoplanin as determined by the standard disk diffusion method. The susceptibilities of these isolates to TMP-SMZ varied.

Cellular fatty acid chromatograms.

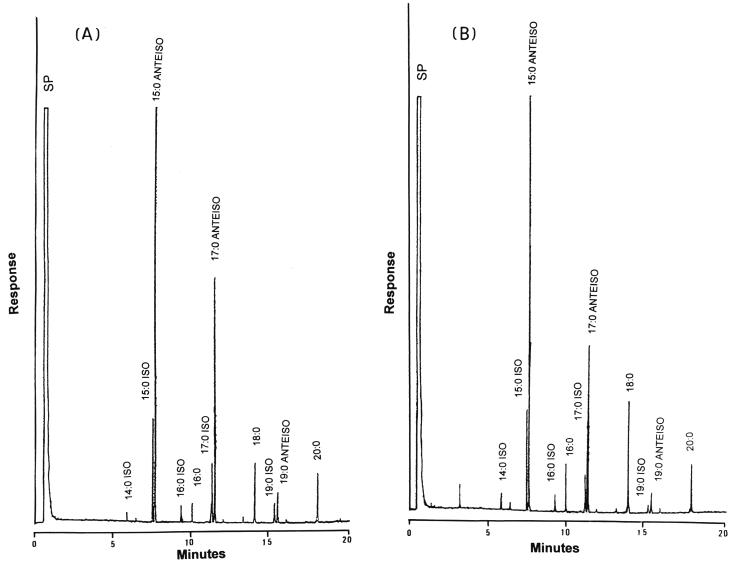

All isolates tested had major peaks (peak area values, ≥3%) of 15:0 ISO, 15:0 ANTEISO, 17:0 ISO, 17:0 ANTEISO, 18:0, 19:0 ANTEISO, and 20:0 and minor amounts (peak area values, 1 to 3%) of 16:0 ISO, 16:0, and 19:0 ISO (Fig. 1). The similarity indices for the identification of S. aureus ranged from 0.75 to 0.85. Two characteristic chromatograms (chromatograms A and B) were identified: all clone 1 and clone 2 isolates belonged to chromatogram A and all clone 3 isolates belonged to chromatogram B. For chromatogram A, the ratio of peak area values for 15:0 ANTEISO (range, 42.3 to 49.0%; mean, 46.1%) and 17:0 ANTEISO (range, 15.2 to 22.4%; mean, 20.3%) was 2.1 to 2.6, and that for 17:0 ANTEISO and 18:0 (range, 4.2 to 6.5%; mean, 5.7%) was 2.9 to 4.4. For chromatogram B, the ratio of peak area values for 15:0 ANTEISO (range, 42.6 to 51.0%; mean, 47.4%) and 17:0 ANTEISO (range, 14.8 to 20.6%; mean, 16.8%) was 2.7 to 3.2, and that for 17:0 ANTEISO and 18:0 (range, 8.0 to 12.4%; mean, 10.1%) was 1.5 to 2.6.

FIG. 1.

Gas chromatograms (A and B) of methylated cellular fatty acids of strains with negative Staphylase reactions and MRSA. SP, solvent peak.

RAPD patterns.

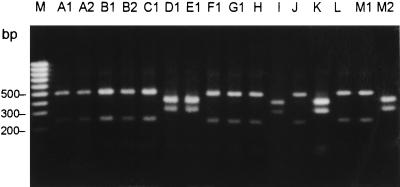

Among the 25 MRSA isolates with negative Staphylase reactions, three RAPD patterns (patterns a to c) were identified (Table 1). Figure 2 shows the RAPD patterns of the 16 slide coagulase-negative MRSA isolates generated by AP-PCR with primers M13 and H12. Except for isolates A1 and A2, B1 and B2, and M1 and M2, these 16 isolates were recovered from different patients. Pattern a (clone 1) comprised 16 isolates, followed by pattern c (8 isolates; clone 3) and pattern b (1 isolate; clone 2). All isolates (except isolate B2) recovered from patients who resided in an ICU (ICU 3B2) had RAPD pattern a, but this pattern was also found for one isolate (isolate J) from another ICU (ICU 3C1). One patient (patient 13) harbored two isolates with two major patterns (patterns a and c, respectively) within an interval of 2 weeks. Two isolates (isolates H and K), both with pattern a, were recovered from patients 8 and 12, respectively, who were discharged from an ICU (ICU 3B2) 2 to 3 days prior to the recovery of the isolates. The RAPD patterns of the 10 MRSA isolates with positive Staphylase reactions were different from those for the 25 isolates tested (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

RAPD patterns of the 16 Staphylase reaction-negative S. aureus and MRSA isolates generated by AP-PCR with primers M13 and H12. Lanes: M, molecular size marker; 1 to 16, isolates A1 to M2, respectively (see Table 1).

Antibiotype.

The antibiotypes of the isolates with the same RAPD patterns were identical. Table 2 presents the MICs of 10 antimicrobial agents for isolates of three antibiotypes. All isolates were highly resistant (MICs, ≥256 μg/ml) to oxacillin, cefazolin, erythromycin, clarithromycin, and clindamycin and were susceptible to quinupristin-dalfopristin. The differences among the three antibiotypes (clones 1 to 3) were the susceptibilities (MICs) to TMP-SMZ and gentamicin.

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities and antibiotypes of 25 isolates of Staphylase reaction-negative S. aureus and MRSA

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml) for indicated antibiotype

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |

| Oxacillin | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 |

| Cefazolin | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 |

| Erythromycin | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 |

| Clarithromycin | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 |

| Clindamycin | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 |

| Rifampin | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Gentamicin | ≥256 | 64 | 128 |

| TMP-SMZ | 0.094 | 0.064 | ≥32 |

| Vancomycin | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Teicoplanin | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

Coagulase type.

Only two coagulase types (type II and IV) were identified. Clones 1 and 2 isolates were coagulase type II, and clone 3 isolates were coagulase type IV. The S. aureus ATCC 29213 strain was coagulase type IV.

RFLP profiles of staphylococcal coagulase gene.

AluI restriction of the amplification products of the staphylococcal coagulase gene obtained by PCR generated two DNA fragments. The three coagulase-negative staphylococci which served as negative controls yielded no DNA amplicons. Two different RFLP profiles (profiles 1 and 2) were identified (Fig. 3). RFLP profile 1 was found for clone 1 and 2 isolates, and profile 2 was found for clone 3 isolates.

FIG. 3.

RFLP profiles of staphylococcal coagulase gene from the 16 Staphylase reaction-negative S. aureus and MRSA isolates. Lanes: M, molecular size marker (100-bp ladder, MBI Fermentas); A1 to M2, isolates A1 to M2, respectively (see Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Despite the significant occurrence of MRSA strains exhibiting negative slide coagulase reactions reported in the literature, it was absent from NTUH prior to the outbreak described here. The commercial Staphylase test was introduced into the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of NTUH in 1990. The manufacturer of the Staphylase test kit declared that it has a sensitivity of 100% after an evaluation with positive results for 1,662 of 1,662 strains of S. aureus. However, with multidrug-resistant S. aureus, this test suffers from inaccuracies similar to those of other slide coagulase tests (1). Kloos and Bannerman (10) mentioned that even if the test was nonreactive the colonial morphology and hemolytic activity of S. aureus on the Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood agar should prompt laboratory personnel to perform additional tests to accurately identify the organisms as S. aureus. However, the lower sensitivity of the Staphylase test among MRSA isolates, especially those isolates that possess the less frequently encountered colonial morphology (cream-white or nonpigmented colonies with a narrow zone of hemolysis or no hemolysis), makes the standard identification tests for the differentiation of different Staphylococcus species crucial. It is especially important at the present time, when the incidence of S. aureus isolates resistant to methicillin in hospitals is increasing.

In Taiwan, commercially available semiautomated identification kits are widely used in clinical microbiology laboratories for the identification of unusual gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria to the species level, especially those recovered from specimens from normally sterile sites. Seven of the 25 MRSA isolates with negative Staphylase reactions were initially identified and reported to be S. haemolyticus or S. epidermidis with the Vitek GPI system, but they were subsequently identified as S. aureus by the tube coagulase test and standard biochemical methods. Therefore, it is impossible to absolutely rule out the existence of slide coagulase-negative MRSA at NTUH prior to December 1997, since standard microbiological methods were not applied to any staphylococcal isolate with a negative slide coagulase reaction.

Previous studies have indicated that the failure of latex agglutination and hemagglutination methods to identify MRSA was highly associated with specific capsular serotypes, in particular, with capsular serotype 5 (2, 3, 10, 25). Ruane et al. (20) observed that failure of the two test methods to identify MRSA strains (failure rate, 23 to 25%) highly correlated (100%) with resistance to TMP-SMZ and rifampin. They further suggested that the results of susceptibility testing with these two agents could predict the false-negative results of the test procedure (20). Wanger et al. (24) described an outbreak among infants in a newborn special care unit and newborn ICU caused by latex agglutination-negative MRSA strains which were susceptible to clindamycin (a finding not frequently seen for MRSA isolates in their hospital) (24). Contrary to the previous observations, one clone (clone 1) of the two major epidemic clones was highly susceptible to TMP-SMZ, and all three clones were susceptible to rifampin and resistant to clindamycin.

Previous studies indicated that the agreement between the MIS and the conventional methods for the identification of Staphylococcus species was 87.8%, whereas the overall identification rate with several commercially available identification kits was 85% (22). Furthermore, the fatty acid chromatogram of S. aureus obtained with the MIS is distinct and can be used to separate these strains from other species (22). In the present study, we further demonstrated that two distinct chromatograms exist for the 25 S. aureus isolates. However, the utility of cellular fatty acid analysis as an epidemiological typing method for S. aureus isolates is limited because different clones (clones 1 and 2) of our isolates had the similar chromatograms.

Analysis of genomic DNA by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis proved to be a useful tool for study of the epidemiological relatedness of staphylococcal isolates (15, 17, 23). However, it is time-consuming; thus, timely recognition of strain relatedness is less likely. The time-saving RAPD analysis generated by AP-PCR has been documented to be a powerful molecular method for the typing of a wide variety of bacteria (7–9). RFLP analysis of the coagulase gene is a new typing method and has been reported to have more discriminatory power than coagulase typing for epidemiological investigations of S. aureus infections in hospitals (11). Nevertheless, it has a lower discriminatory power than the DNA macrorestriction method, which makes it less suitable as a single typing method (6, 21, 23). Our findings support these previous observations. Among the five typing methods used in the present study, only antibiotyping and RAPD analysis by AP-PCR provided good clonal delineation of the isolates.

In conclusion, two points regarding the antimicrobial susceptibilities, cellular fatty acid analysis profiles, and molecular epidemiology of the 25 MRSA isolates with negative Staphylase reactions are of particular significance. First, the cluster of isolation of MRSA isolates with negative Staphylase reactions during a 4-month period was subsequently documented as an outbreak caused by two clones of this unusual phenotype of MRSA which were disseminated in several ICUs. Second, standard identification methods, instead of commercial identification kits, should be used for the identification of each staphylococcal isolate, especially S. aureus (MRSA) strains with less encountered colonial morphologies and negative Staphylase reactions. These steps are essential for the early recognition of strains and the initiation of infection control measures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cremer A W, Gruneberg R N. Assessment of a new test (Staphylase™) for the identification of Staphylococcus aureus. Med Lab Sci. 1988;45:221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fournier J M, Bouvet A, Boutonnier A, Audurier A, Goldstein F, Pierre J, Bure A, Lebrun L, Hochkeppel H K. Predominance of capsular polysaccharide type 5 among oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1932–1933. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.10.1932-1933.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fournier, J. M., A. Boutonnier, and A. Bouvet.Staphylococcus aureus strains which are not identified by rapid agglutination methods are of capsular serotype 5. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1372–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Fournier J M, Bouvet A, Mathieu D, Nato F, Boutonnier A, Gerbal R, Brunengo P, Saulnier C, Sagot N, Slizewicz B, Mazie J C. New latex reagent using monoclonal antibodies to capsular polysaccharide for reliable identification of both oxacillin-susceptible and oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1342–1344. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1342-1344.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goh S H, Byrne S K, Zhang J L, Chow A W. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus on the basis of coagulase gene polymorphisms. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1642–1645. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1642-1645.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoefnagels-Schuermans A, Peetermans W E, Struelens M J, van Lierde S, van Eldere J. Clonal analysis and identification of epidemic strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by antibiotyping and determination of protein A gene and coagulase gene polymorphisms. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2514–2520. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2514-2520.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsueh P R, Teng L J, Yang P C, Chen Y C, Ho S W, Luh K T. Persistence of a multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone in an intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1347–1351. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1347-1351.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsueh P R, Teng L J, Ho S W, Hsieh W C, Luh K T. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of Flavobacterium indologenes infections associated with indwelling devices. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1908–1913. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.8.1908-1913.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsueh P R, Teng L J, Lee P I, Yang P C, Huang L M, Chang S C, Lee C Y, Luh K T. Outbreak of scarlet fever at a hospital day care centre: analysis of strain relatedness with phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. J Hosp Infect. 1997;36:191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(97)90194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kloos W E, Bannerman T L. Staphylococcus and Micrococcus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 282–298. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi N, Taniguchi K, Kojima K, Urasawa S, Uehara N, Omizu Y, Kishi Y, Yagihashi A, Kurokawa I. Analysis of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus by a molecular typing method based on coagulase gene polymorphisms. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:419–426. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005857x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lairscey R, Buck G E. Performance of four slide agglutination methods for identification of Staphylococcus aureus when testing methicillin-resistant staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:181–182. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.1.181-182.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lally R, Woolfrey B. Clumping factor defective methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1984;3:151–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02014336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luijendijk A, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H, Kluytmans J. Comparison of five tests for identification of Staphylococcus aureus from clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2267–2269. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2267-2269.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulligan M E, Arbeit R D. Epidemiologic and clinical utility of typing systems for differentiation among strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1991;12:20–28. doi: 10.1086/646234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulligan M E, Murray-Leisure K A, Ribner B S, Standiford H C, John J F, Korvick J A, Kauffman C A, Yu V L. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a consensus review of the microbiology, pathogenesis, and epidemiology with implications for prevention and management. Am J Med. 1993;94:313–328. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90063-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nada T, Ichiyama S, Osada Y, Ohta M, Shimokata K, Kato N, Nakashima N. Comparison of DNA fingerprinting by PFGE and PCR-RFLP of the coagulase gene to distinguish MRSA isolates. J Hosp Infect. 1996;32:305–317. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(96)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standard for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Eighth informational supplement. NCCLS document M100-S8. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piper J, Hadfield T, McCleskey F, Evans M, Friedstrom S, Lauderdale P, Winn R. Efficacies of rapid agglutination tests for identification of methicillin-resistant staphylococcal strains as Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1907–1909. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1907-1909.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruane P J, Morgan M A, Citron D M, Mulligan M E. Failure of rapid agglutination methods to detect oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:490–492. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.3.490-492.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarzkopf A, Karch H. Genetic variation in Staphylococcus aureus caogulase genes. Potential and limits for use as epidemiological marker. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2407–2412. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2407-2412.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoakes L, John M A, Lannigan R, Schieven B C, Ramos M, Harley D, Hussain Z. Gas-liquid chromatography of cellular fatty acids for identification of staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1908–1910. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1908-1910.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tenover F C, Arbeit R, Archer G, Biddle J, Byrne S, Goering R, Hancock G, Hebert G A, Hill B, Hollis R, Jarvis W R, Kreiswirth B, Eisner W, Maslow J, Mcdougal L K, Miller J M, Mulligan M, Pfaller M A. Comparison of traditional and molecular methods of typing isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:407–415. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.407-415.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wanger A R, Morris S L, Ericsson C, Singh K V, LaRocco M T. Latex agglutination-negative methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus recovered from neonates: epidemiological features and comparison of typing methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2583–2588. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2583-2588.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkerson M, McAllister S, Miller J M, Heiter B J, Bourbeau P P. Comparison of five agglutination tests for identification of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:148–151. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.148-151.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]