Abstract

Academic Health Centers (AHCs) across the nation are experiencing a reawakening to the importance of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI). Such work impacts both employees and patients served by healthcare institutions. Yet, for departments without previously existing formal channels for this work, it is not always apparent where to begin. The current manuscript details a process for creating a committee as a vehicle for championing DEI efforts at the department level within an AHC. The authors present a six-step model for forming a DEI Committee and progress monitoring measures to remain accountable to identified objectives. In each step, the authors provide examples of their work with the goal for readers to tailor and apply each step to their own departments’ DEI efforts. The current paper also identifies lessons learned with regard to barriers and facilitators of department-level DEI work. Reflections and next steps for DEI work beyond the proposed model are also discussed.

Keywords: Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Climate, Departmental initiatives

Introduction

The problem of systemic and institutionalized oppression has been well-recognized by many across public health broadly and medicine specifically (Hardeman, Medina, & Kozhimannil, 2016a; Hardeman et al., 2016b, 2018; Feagin & Bennefield, 2014; Wright, Jarvis, Pachter, & Walker-Harding, 2020). During the summer of 2020, the world had a re-awakening to the depth and breadth of these influences following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. Across many medical schools and healthcare institutions, leaders and employees broadly recommitted to values of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI; Gray II et al., 2020; Morse & Loscalzo, 2020). Leadership from both the American Psychological Association (APA), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), and many other professional organizations have expressed urgency around issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion (American Psychological Association, 2021; Association of American Medical Colleges, 2021). These DEI values are also central to topics addressed in accreditation and trainee competencies both within the field of psychology (e.g. Individual and Cultural Diversity Profession-Wide Competencies; American Psychological Association Standards of Accreditation for Health Service Psychology, 2015) and across professions. Table 1 depicts some examples of the ways in which some programs have begun to address this need. However, many found themselves pausing without a guide for best practices around how to put these espoused values into action. There are many ways to begin, and almost no ‘wrong’ place to start, but the idea of “start somewhere” has never been more true. To that end, this paper will detail the process for beginning a committee as a vehicle to champion efforts related to DEI within an academic health center department with the goal of sustaining an institutional climate for diversity that is reinforced with efforts towards inclusion and equity. Experiences shared in this paper draw upon three years of experience, which began prior to the 2020 reawakening, in a department which had not previously had a committee focused on DEI. This paper operationalizes a DEI Committee as the mechanism for many types of needed changes and will provide the basic blueprints to create this vehicle for affecting change at the department level. Just like true vehicles, however, the specific “model” will vary by department and context. Specific examples of activities, lessons learned, and next steps will help guide thinking of those considering starting similar initiatives. Our overarching goal is that this structure will allow colleagues in academic health centers and medical schools to use this knowledge to address systemic oppression from grassroots level (“bottom up”) while larger efforts are beginning/continuing at higher levels of leadership/systems (“top down”).

Table 1.

National professional academic health organizations DEI resources and engagement

| Organization | Description | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) | Provides toolkits for DEI assessment and strategic planning, articles and resources, and information on initiatives | https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/diversity-inclusion |

| American Psychological Association (APA) | Offers a framework to provide “an intentional and systemic approach to infusing EDI into our work” | https://www.apa.org/about/apa/equity-diversity-inclusion |

| Association of Psychology Postdoctoral and Internship Centers (APPIC, 2021) | Statement of values and process steps | https://www.appic.org/About-APPIC/APPIC-Diversity-Statement |

| Society of Clinical Psychology (APA Division 12, 2021) | Stated goals, list of resources for diversity in psychology | https://div12.org/diversity/ |

Defining Terms

Within the politically and racially charged atmosphere of the United States in the present day, there is increasing awareness of inequities and discourse on the experience of oppression. In this context, it is important that we clarify the terms we use throughout this paper with a view of developing a shared language that unites our understanding and provides momentum for positive change. Diversity is the range of individual and group differences including but not limited to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, country of origin, culture, age, physical and mental ability, spiritual/religious beliefs, gender identity and sexual orientation (Tan, 2019). Equity refers to an approach that ensures that everyone has access to the same opportunities (Nivet et al., 2008). It is the leveling of the playing field of individuals with different starts, advantages or disadvantages: it is a system that is just, impartial and fair.1 Equity starts with inclusion. Inclusion refers to the intentional, ongoing effort to ensure that diverse people with different identities are able to fully participate in all aspects of the work of an organization, including leadership positions and decision-making processes. Inclusion is an unconditional sense of belonging in a group or an organization—a feeling of being valued which results in empowered participation (Tan, 2019). Important identified aspects of inclusion include acknowledging differences among people and recognizing the value of those differences (Holvino, Ferdman, & Merrill-Sands, 2004), removal of obstacles to participation/contribution (Roberson, 2006), acceptance and being treated as a valued group member, an “insider,” and fostering belonging while allowing individuals to retain their uniqueness within the group (Shore et al., 2011). Inclusion is nurtured in an institutional climate that truly values diversity and is defined as “the perceptions, attitudes, and expectations that define the institution, particularly as seen from the perspective of individuals of different racial or ethnic backgrounds (Institute of Medicine Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the U.S. Healthcare Workforce, 2004). Research consistently demonstrates the value of including different viewpoints for learning and overall organizational outcomes (Smith, 2012).

Background

It is well-documented that environments with more diverse individuals bring a greater range of perspectives that can increase productivity and innovation (Forbes, 2011; Hong & Page, 2004; Levine, 2020; Saxena, 2014). Within the academic healthcare (AHC) context, patient care is positively impacted by the presence of a diverse group of healthcare professionals (Gomez & Bernet, 2019; Hill, Jones, & Woodworth, 2020a; Hill et al., 2020b). Positive psychological impacts are also found where an affirming and inclusive climate is present (Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013). Conversely, an institutional climate where there is a presence of student or faculty dissatisfaction, or experiences of bias can have tremendous impact across roles (Hardeman et al., 2016a, b; Pololi, Cooper, & Carr, 2010; Price et al., 2005). Additionally, student and faculty experiences of bias have a secondary negative impact on patient populations (Institute of Medicine Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the U.S. Healthcare Workforce, 2004). Additionally, growing evidence of challenges faced by under-represented minorities (URM) and historically excluded populations within AHCs exists. For instance, URM faculty are more likely to report systemic experiences of exclusion, experiences of bias, lower levels of professional satisfaction, isolation/feeling invisible, lack of mentoring/role models/social capital, different performance expectations related to race/ethnicity, the unfair burden of being identified with affirmative action and responsible for diversity efforts, and financial hardship (Nivet et al., 2008; Pololi et al., 2012). In addition to these challenges, microaggressions in the workplace result in URM faculty feeling unsupported and making a choice to leave academic medicine, perpetuating a cycle of unequal URM participation in academic healthcare systems (Smith, 2012).

Taken together, creating a positive climate of DEI is crucial to the success of any academic department, its members, and the patients/participants served by the department. Yet broad, institutional changes are difficult, long-term undertakings which take time. For DEI-focused change, a systemic shift starting with the leadership, fostered by the individuals charged to pursue a climate of equity and inclusion and fanned by each participating member of the team, is the urgent need of the hour.

Broader commentary on institutionalized racism, and specifically in the context of AHCs, and its deleterious effects is relevant here but beyond the scope of this paper. The interested reader is encouraged to review previously mentioned papers (e.g., Hardeman et al., 2016a, b). It is outside the scope of this paper to further detail each specific type of discrimination and antidiscrimination work within those specific areas; these could easily be (and are) their own papers (e.g., disability: Meeks & Herzer, 2016; Meeks & Jain, 2018; Meeks & Neal-Boylan, 2020; VanPuymbrouck, Friedman, & Feldner, 2020; sexual orientation: Hill et al., 2020a, b; Lu et al., 2020; Vargas et al., 2020; gender: Agrawal, Madsen, & Lall, 2019; Borlik et al., 2021; Richter et al., 2020). Specific DEI terms used in this paper are defined above to ensure a common understanding. The principles discussed center the urgent focus of racism, but also apply to sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, ableism, and other forms of discrimination, harassment, and exclusion.

DEI Climate Work

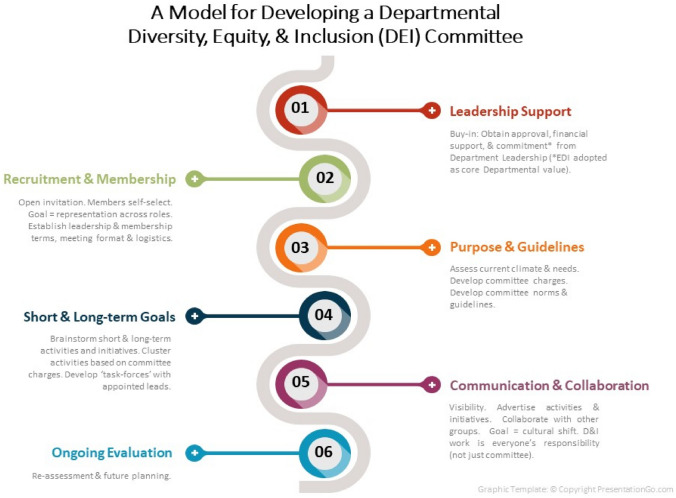

Broadly, the purpose of a DEI Committee within an academic medical department is to foster a psychologically safe working and learning environment for a diverse body of faculty, staff, and learners, which in turn benefits patient experience and outcomes. Inherently, it incorporates diversity, equity, and inclusion goals. Additionally, these goals are directly related to the wellness and retention of faculty, staff, and learners. While emerging literature has focused on specific processes and policies related to DEI topics (e.g., Paul-Emile et al., 2020; Sotto-Santiago et al., 2020), little research exists that focuses on addressing medical school departments’ institutional DEI climate. The little that does exist tends to focus on broad needs (e.g., Diaz, Navarro, & Chen, 2020) or faculty/staff perceptions that illuminate current areas for improvement (e.g., Price et al., 2009). In order to affect sustained change related to DEI, it is necessary to reframe equity, diversity, and inclusion as central to institutional effectiveness and build institutional capacity for this work (Holvino et al., 2004). Additionally, DEI work must be explicitly linked to institutional strategic plans/goals (Carethers, 2020). A helpful model posed by Carnes, Handelsman and Sheridan (2005) also notes the importance of various ‘stages of change’ that may exist when contemplating broad DEI-related shifts in academic medicine policies and practices. Kim et al. (2019) note the importance of a committee and the potential impact on a department, but do not detail the process of development or the potential bidirectional impacts of departmental initiatives on broader institutional goals. This gap illustrates the need and role of the current paper and the model depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A model for developing a Departmental Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Committee

Committee/Institution Background

This committee and our efforts began approximately 4 years ago in a department that previously did not have a committee or group focused on equity, diversity, and inclusion. Although these ideals were discussed in various sectors and there was support for related initiatives, a clear infrastructure did not yet exist. The group formed was largely a grassroots effort that began with an open call for membership. Over the following years, the DEI Committee grew in size and in its undertakings. We quickly observed a “spillover effect” as members of the committee returned to their ‘home’ sectors/groups/teams bringing with them conversations focused on DEI. Additionally, faculty and staff began to see areas for improvement related to DEI where they had previously gone unnoticed.

Importantly, the efforts around DEI in our department and the current paper was first created well before the COVID-19 global pandemic. In the following months, the provision of medicine and mental health services shifted drastically beginning in March 2020 due to COVID-19 public health restrictions (i.e., increases in telehealth, shifts in work responsibilities, renewed conversations about wellness and burnout). Our DEI efforts also preceded the global re-awakening to racial injustice that occurred following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Increased public awareness of and focus on racial disparities between white and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) members of society across an array of health and safety outcomes, gave new light to the public health crisis of racism in America (Devakumar et al., 2020). Along with a national and global society, our local community reckoned with the resulting civil unrest and racial trauma (Comas-Díaz, Hall, & Neville, 2019) experienced by many BIPOC individuals. In addition to the COVID-19 pandemic, many fields began to recognize and explicitly name the concurrent “racism pandemic” (e.g., APA, 2020) that resulted in far reaching disparities across various health and safety outcomes on children and families of color. Layered on top of the COVID-19 pandemic, the constellation of these events resulted in “dual pandemics.” Within our academic department, the timing (and location) of these historic events provided an important opportunity for deeper conversations, increased buy-in, and stronger commitment to existing DEI efforts spearheaded by our committee. Below (Step 5, Lessons Learned), we describe the specific impacts of these events further as well as the institutional developments that supported our efforts specifically and the sustainability of DEI work broadly.

Approach/Model

This paper builds on previous work highlighting the need for systemic change to mitigate systems of oppression by focusing on how individual departments can begin to affect local change (bottom up) in tandem with broader institutional efforts (top down). We provide a model (Fig. 1) for DEI Committee development used at the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Sciences at the University of Minnesota that can be adapted for individual institutional departments, clinics, or disciplines. The model can be applied flexibly to fit the unique needs of a given department. We use specific examples to illustrate how to build a culture that fosters accessibility and inclusion and practices antiracism to dismantle historical systems of oppression; individual departmental needs and priorities will vary. However, the broader step-by-step approach to building a DEI Committee (or revamping an existing committee), offered based on our experience, is designed to be more universally applicable.

Step 1: Leadership Support

An imperative first step is obtaining commitment to and investment in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) as core values from departmental leadership. We sought support that extended beyond lip service, checked boxes, and improving statistics. DEI was conceptualized as critical to institutional success, excellence in healthcare delivery, medical and interprofessional education, and advancements in research. We sought to eliminate discrepancies between espoused values and practice. Ideally, at least one member of the department leadership team would serve on the DEI Committee. The overarching goal is to create a natural channel of communication and ensure engagement and commitment from leadership towards broader department initiatives. We recognize that leadership structures look differently across departments. So, it is important to note that representation from leadership on a DEI Committee may align with these differences. For instance, in some smaller departments it may make sense for the Department Head to be involved in Committee meetings. In larger departments, this may not be feasible, but a representative from a leadership team/body may suffice. If needed, extensive literature from corporate and business research can be used to build buy-in and substantiate the value of diverse teams and inclusive environments for cohesion, productivity, and innovation when faced with resistance or apathy from leadership (Catalyst, 2020; Page, 2017).

Early financial investment by leadership into DEI efforts provided a strong demonstration of commitment. We were granted departmental funds and additionally applied for institutional small grant funding. DEI work can be expensive, time consuming, and labor intensive, especially for marginalized individuals who often bear the brunt of such work e.g., the “Minority Tax” (Campbell & Rodríguez, 2019; Carson et al., 2019; Mustapha & Eyssallenne, 2020; Rodríguez et al., 2015). Specifically, financial support allowed for funding speakers as DEI-related experts are often invited to give talks without appropriate compensation (e.g., Mustapha & Eyssallenne, 2020), covering clinical time or other responsibilities to attend training sessions, providing productivity time/credit to those leading or working on DEI efforts, supporting DEI events which have logistical costs, and more. The most appropriate uses of funding may vary based on the departmental focus/need. Finally, securing established financial support is an important step towards committing to DEI practice and sustaining the fruits of such labor at an institutional level.

Step 2: Recruitment and Membership

Building a successful DEI Committee starts with thoughtful membership recruitment efforts. We sent out an ‘open call’ to all department members. This serves two important purposes: first, it allows members to self-select, which organically brings individuals who are passionate about and motivated to do the work. Genuine commitment to advancing DEI motivates, dedication of time, and effort beyond committee meetings are highly beneficial. Secondly, an open membership invitation promotes greater inclusivity across departmental roles (staff, faculty, students, trainees) and divisions (research, education, clinical), thus ensuring broad perspectives are represented in committee conversations and decisions. In-person recruitment via conversations with individuals or teams may be helpful.

Once a representative group was self-selected, the committee structure and logistics were determined as a group (e.g., membership terms, levels of commitment, leadership, meeting format/frequency—open vs. closed to others). These elements will vary widely by department and can be determined based on department culture and needs. Of particular note is the impact of the global pandemic, racial injustice reckonings, and the availability of remote access to events and meetings. This is further discussed in “Lessons Learned” section.

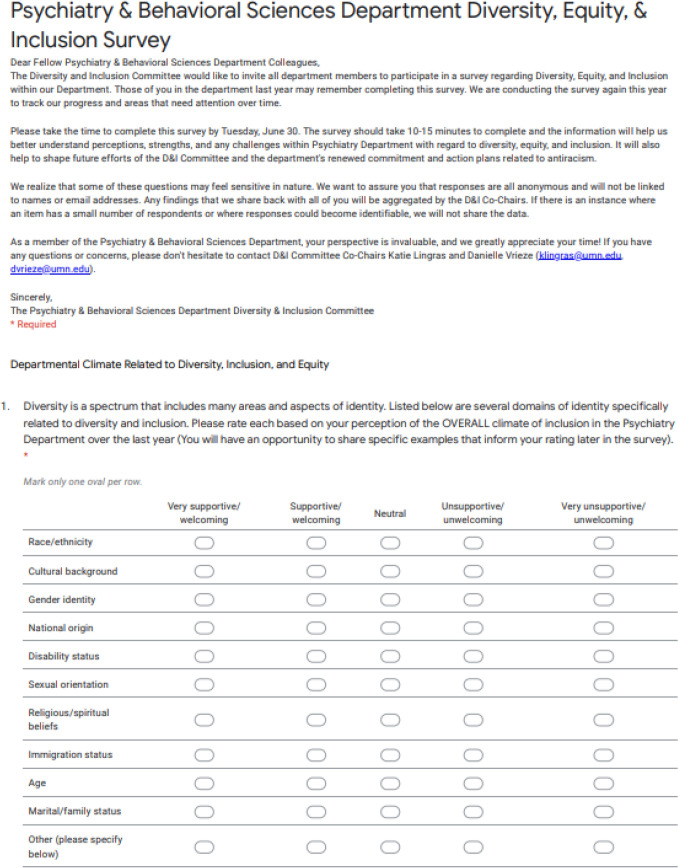

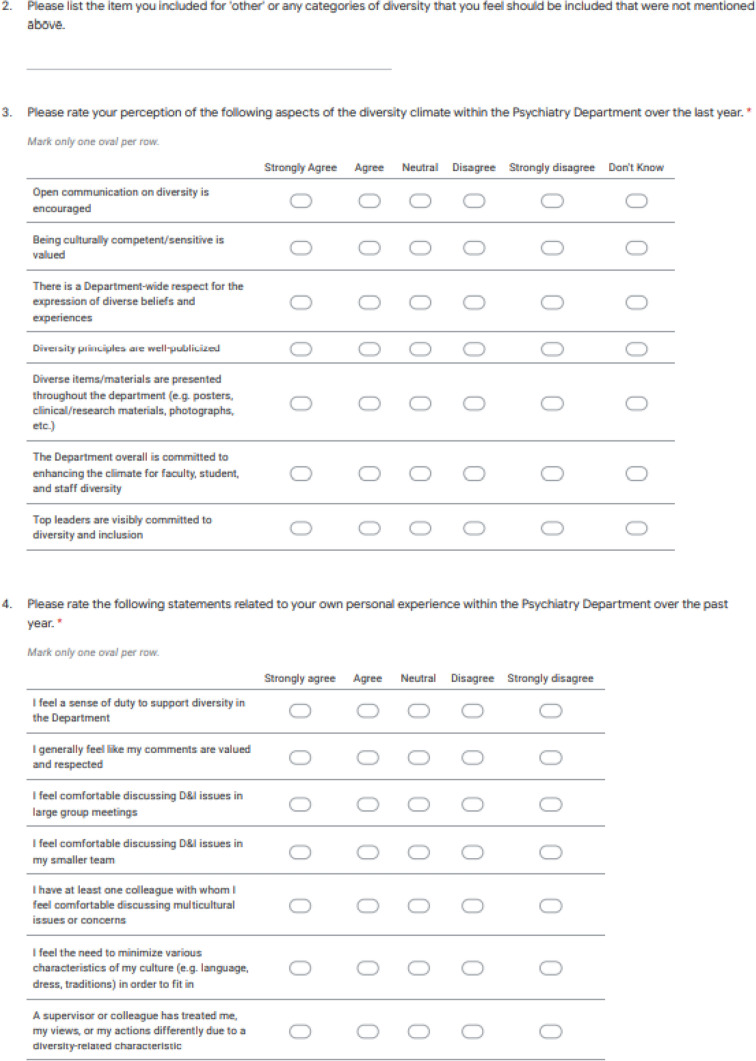

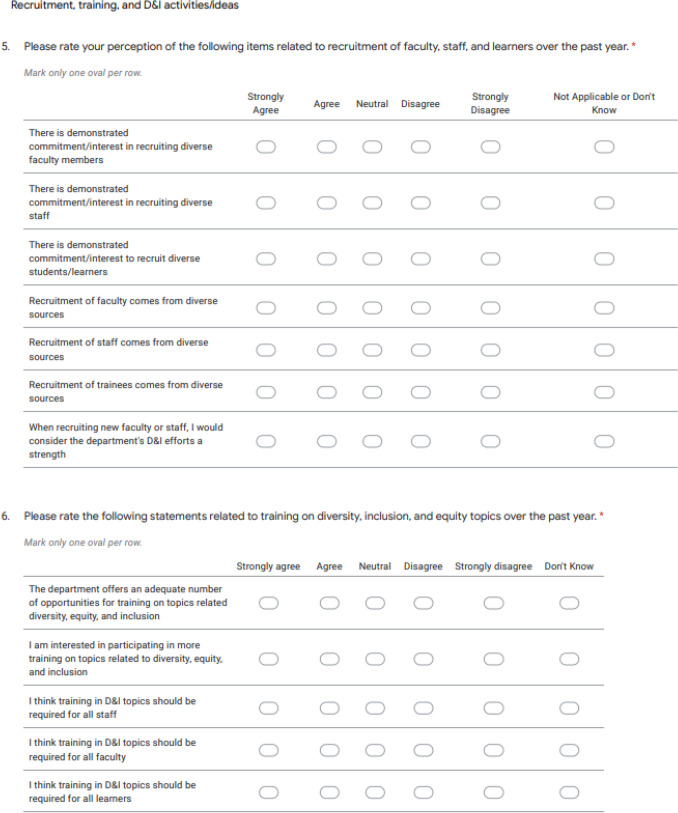

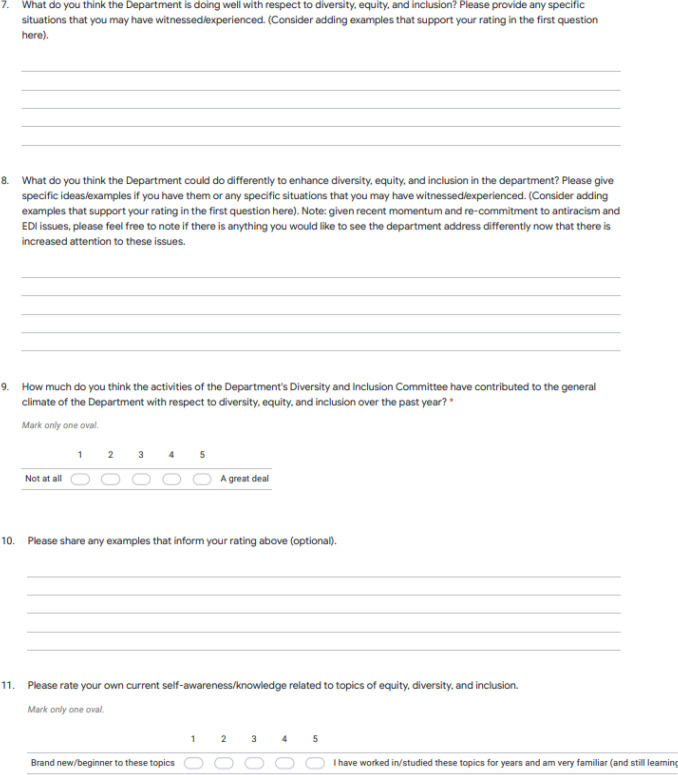

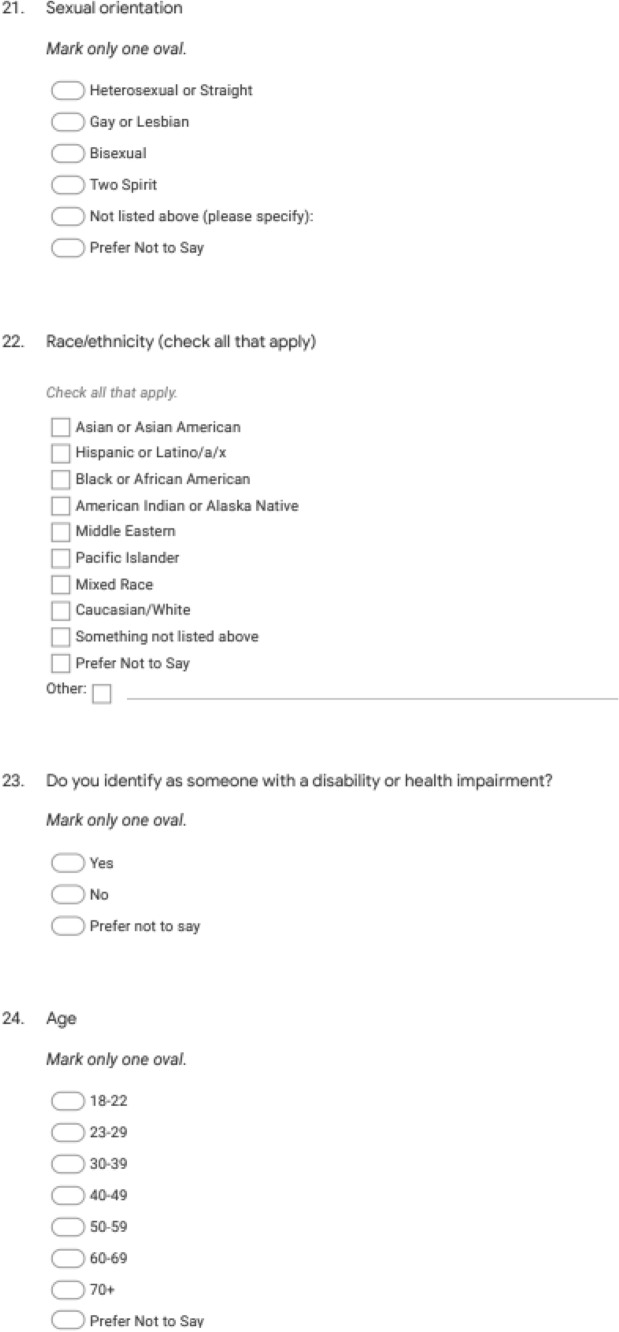

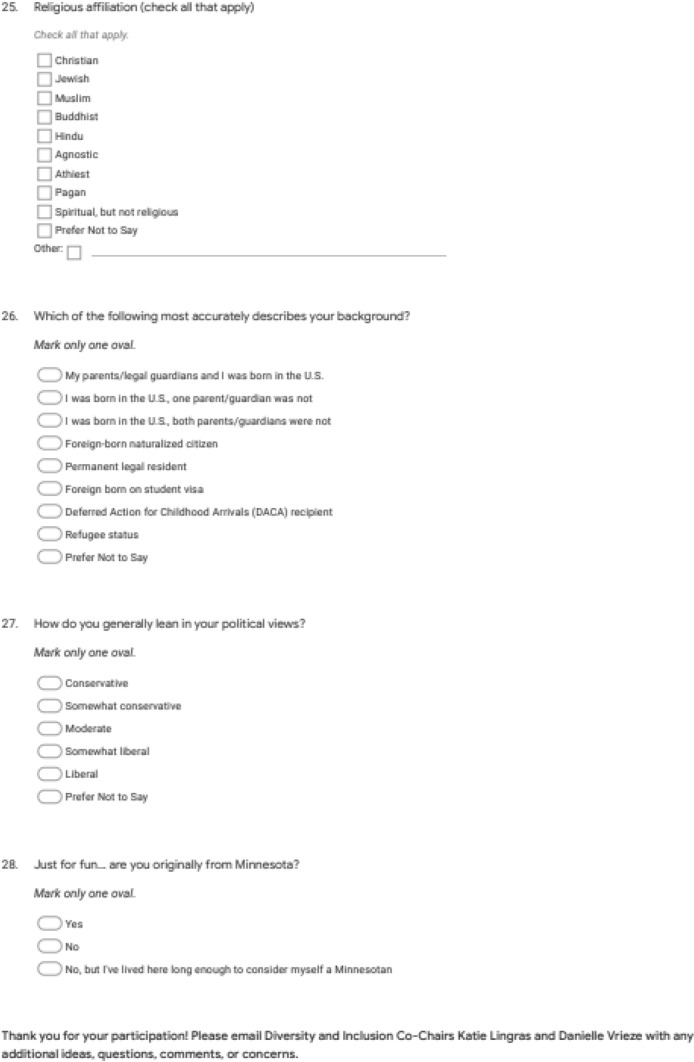

Step 3: Purpose and Guidelines (Mission)

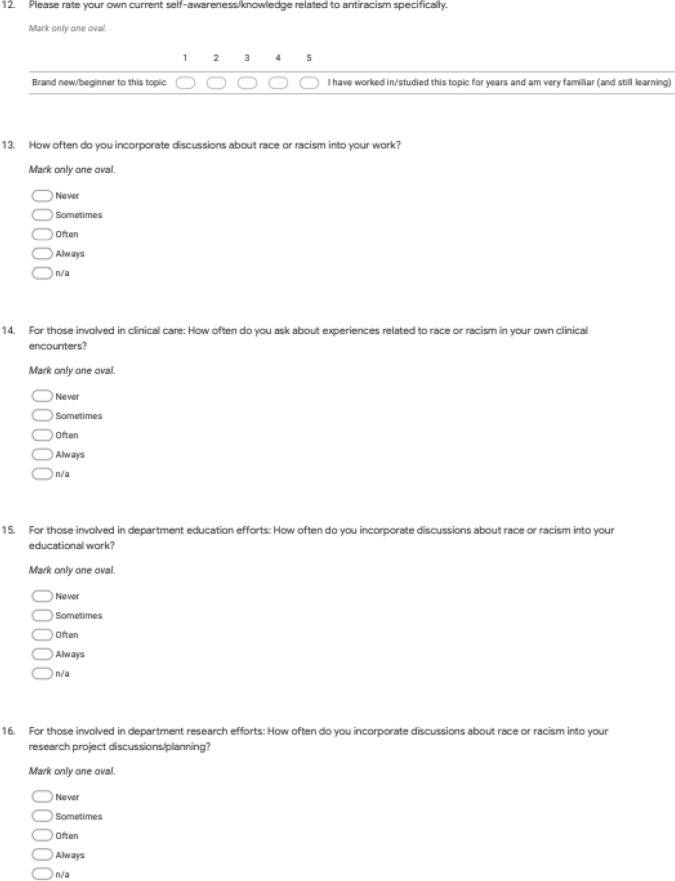

Central to any committee is a clear purpose or mission. At the outset, ideas for the initial charges were suggested by the Department Head; these charges formed the basic structure for the purpose and mission of the group. In order to identify/confirm the focus of the committee’s charges, we conducted a thorough assessment of the current departmental climate and needs. We conducted a department-wide survey based on the Diversity Engagement Survey (Plummer et al., 2012) to assess diversity, sense of belonging, perceived efforts around inclusivity, recruitment and retention, training, areas of strength and growth (see “Appendix” section). Results of this assessment are discussed in Step 6 and informed development of committee charges (i.e., recruitment/retention efforts, fostering an inclusive climate, developing culturally responsive clinical care and research practices). This data was used as a baseline measure and also to demonstrate DEI needs to leadership teams. It also allowed us to ensure that the efforts and initiatives of the committee were integrated with department-wide (cross-sector) needs and, later, with the institutional efforts at the medical school level. These collaborative efforts are further detailed in Step 5.

We also sought to establish committee norms and guidelines for fostering respectful discourse and collaborative work. A foundation of trust and respect among committee members doing challenging DEI work is imperative. While these are necessary qualities for any working group, this foundation is even more central to DEI work which relies heavily upon a genuine, collaborative environment where members feel fully and equally valued and heard. This is particularly important for members of historically marginalized groups who may have personal or collective experiences around exclusion within academic institutions. Our guidelines include things such as: speaking from the “I” perspective, listening actively, step up/step back (if you are typically the first to speak, consider stepping back to allow space for others/if you do not typically speak in groups, challenge yourself to contribute thoughts), respect silence, share even if you don’t have the right words, uphold confidentiality, lean into discomfort, and “ouch/oops” (acknowledging that mistakes will be made and offering an approach for signaling harm and strategies for repairing, and committing to listening and learning). As noted above, these guidelines are important for building a foundation of trust and collaboration in the DEI space. We open each meeting with an introduction exercise that invites people to connect and practice reflection. These range from simple “get to know you” questions (e.g., favorite place you have traveled) to deeper reflection questions (e.g., share something new you have learned within the DEI realm; share a time you experienced or witnessed a microaggression) with the goal of increasing engagement, trust, and connection over time.

Step 4: Long and Short-Term Goals

Once DEI Committee charges were established, we facilitated brainstorming long and short-term goals. We encouraged ideas to include bold, big picture initiatives as well as small, simple projects. Collectively, a variety of simultaneous and ongoing initiatives (both large- and small-scale) allowed for deeper, more impactful work than one-off events. Although one-time efforts may generate interest, they cannot create sustainable change. Furthermore, ongoing opportunities allowed larger numbers of department members to engage in DEI activities and efforts.

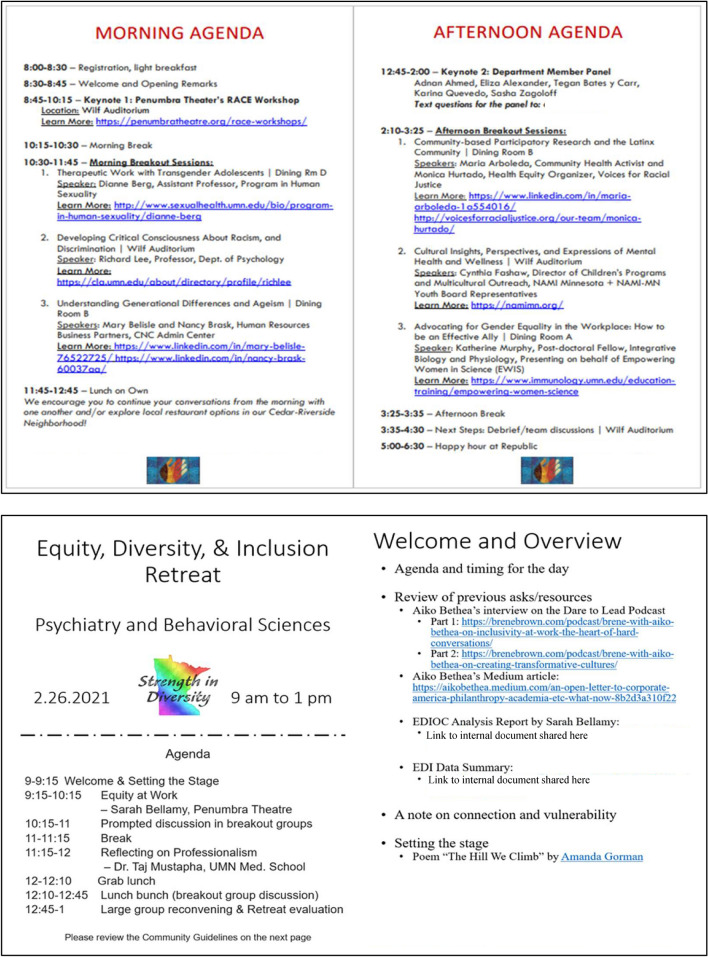

Next, we clustered activities based on themes associated with established committee charges. We created task-forces for each activity cluster and identified group leads for each task force. Additionally, each task force developed an action plan to move projects forward between committee meetings, including small projects (e.g., add DEI values/efforts to the department website, post signs to signal DEI commitment) while simultaneously making progress on larger action points. Some of our larger initiatives included creating a brochure for prospective students and faculty highlighting DEI opportunities/resources at the university and surrounding metro area. The committee also organized both full-day (2018) and half-day (2021) whole-department DEI retreats with didactics and reflective opportunities on topics such as critical consciousness about racism and discrimination, therapeutic work with transgender adolescents, and community-based participatory research within the Latinx community. In 2021, we held the retreat virtually due to the pandemic, so we opted for a shorter day together to preserve engagement. However, we again provided opportunities for large-group didactic presentation from outside speakers and then breakout discussion opportunities. Topics were tailored to developments within the department DEI work and included a focus on microaggressions and professionalism, with inclusion of specific tools that could be immediately put into action (see Fig. 2 for retreat program examples). These topics are just examples of the many specific learning opportunities that could be chosen. We recommend choosing a mix of introductory and ‘deeper dive’ topics in order to cater to a range of learning levels and styles. Additionally, it is important to choose topics that are most reflective of/relevant to the individual department’s internal and external community.

Fig. 2.

Examples of DEI retreat programs, detailing full- and half-day DEI retreat content

We engaged an external consultant to conduct a strategic plan analysis to guide the formation of short- and long-term DEI goals as our work gained momentum. The process included focus groups with key stakeholder groups across sectors and roles of the department. The results were compiled into a summary that was made available to the entire department to facilitate transparency and accountability. Additionally, recommendations and next steps suggested in the summary provided a roadmap for shaping future activities and linking those activities to strategic plans/goals. For instance, when a theme related to the inherent tension between department culture norms and a desire for diversity emerged, we made it a priority to focus on this topic as part of the subsequent departmental retreat and to make space for deeper discussion. Similarly, the need for a universal mandate for DEI work was consistent feedback we had received in previous years and allowed us to spend time in leadership discussions as well as full-department meetings/retreats addressing questions of department-wide goals/requirements related to DEI work.

Throughout our work, an important long-term goal was to infuse DEI perspectives and goals into work across the department. As such, once the committee was established and momentum around DEI initiatives grew across sectors, we endeavored to serve as consultants to these efforts rather than to “house” them all in the DEI Committee. This approach also allowed for individuals in the department to consider opportunities for a DEI focus within their own areas of expertise/interest, while increasing the prevalence and visibility of DEI efforts across the department. For instance, rather than identify a member of the DEI Committee to serve on every search committee, we consulted on guidelines created for a more diverse and equitable approach to recruitment and retention. We also recommended a systematic approach to include a DEI lens for every search which involved identifying a person to “hold” the DEI perspective for the group. By identifying an individual to keep tabs on this important perspective for the group, it allowed for everyone to be responsible for this effort rather than placing the responsibility with a member of the Committee. Additionally, this infused approach helped to decrease the burden and potential burnout that is often experienced by committee members, who tend to disproportionately include members from marginalized identities. This was especially important during 2020 when there was a tremendous uptick in requests for DEI training and activities nationally following George Floyd’s death and the subsequent racial injustice reckonings.

Additional examples of toolkits, frameworks, approaches, values, goals, and resources related to DEI efforts across academic medicine and psychology are depicted in Table 1. As we discuss in Step 5, communication and collaboration across likeminded groups is central to broader DEI-related progress across academic medicine.

Step 5: Communication and Collaboration

We learned that advertising events and opportunities, espousing values, and showcasing successes is important for several reasons. First, increased visibility leads to increased awareness of DEI efforts for department members, patients, and visitors. This also maintains momentum of ongoing work, allowing for deeper impact and sustainable change and accountability to espoused goals/values. Finally, ongoing communication fosters a gradual, collective adoption of DEI as values embedded into departmental culture. Collaboration with other departmental groups can ensure that a DEI lens is adopted across sectors and initiatives, making DEI work a collective responsibility among department members.

We found that there were other departments and programs doing similar DEI work within the Medical School, at the University of Minnesota’s Office for Equity and Diversity, and in University departments outside of the Medical School. Crosstalk and collaboration with these groups allowed opportunities to learn about work already in progress, available resources, and what has worked (or not worked). In many cases, partnering with other groups allowed for a greater impact by increasing human and logistical resources and was essential to the success and sustainability of our work. For instance, a Medical School level DEI Committee was created in 2019, and cross-membership with individuals from our department’s committee provided an opportunity to maintain continuity with the larger system’s goals and work.

As part of the Medical School DEI Committee work, a Vice Dean position and Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion was created in 2019, with hiring of the Vice Dean in early 2020. This larger systems-level voice and representation on it allowed for bidirectional communication about existing DEI needs and developing activities to address those needs. Simultaneously, many other departments had begun similar efforts, so the Medical School Committee allowed for communication and collaboration across departments for efforts that were universal and/or relevant to multiple departments. For instance, when multiple departments made requests for adding equity and diversity information to their websites, an adjustment to the standard template was made; this was more difficult to accomplish as a one-off request, but with multiple departments making similar requests, it became more easily implementable. In other efforts, such as department-level activities, it became possible to learn from one another and draw on each other’s experiences and to improve activities with each iteration.

The above collaborations include examples of outreach and dissemination. While dissemination is typically beyond the scope of a traditional committee, individuals who are interested in this work may find both personal and professional benefits to engaging in dissemination efforts. For instance, giving talks to and with other departments, presenting at professional conferences, and information-sharing across local training programs or state psychological (and other professional) organizations can raise awareness and contribute to a common body of knowledge that prevents “reinventing the wheel” for common challenges. Publishing on DEI Committee models and processes in both peer-reviewed journals and venues that are accessible across professions and institutions can also be a helpful way of advancing the broader work. It is important to note, however, that this work of dissemination can be time-consuming, so committees should be cautious about requiring this on top of the work of the group in order to avoid burnout of members. Additionally, it is important to acknowledge and account for the time and impacts of those who do choose to take on these types of efforts.

Findings

Step 6: Ongoing Evaluation

Below we describe the outcomes of some of our work, highlighting the process for Step 6, the on-going evaluation, as an important outcome of this model.

Preliminary Assessment and Results

An essential component of building a DEI Committee includes preliminary and on-going evaluation. A needs assessment as described in Step 3 helped to assess the current status of the department climate with respect to DEI variables and to make the case for needed work. For instance, one of the ways in which we identified needs was to examine the extent to which department members felt various aspects of identity were welcomed. Importantly, we looked at averages but also took a more nuanced view, wherein we considered areas where one or more individuals identified dissatisfaction with a given facet of the department’s climate of inclusivity. Here we wanted to ensure that averages across experiences did not erase individual experiences. Even if the experiences were common to fewer individuals, to ignore them and focus on the average scores would be a disservice to the inclusion component of DEI work.

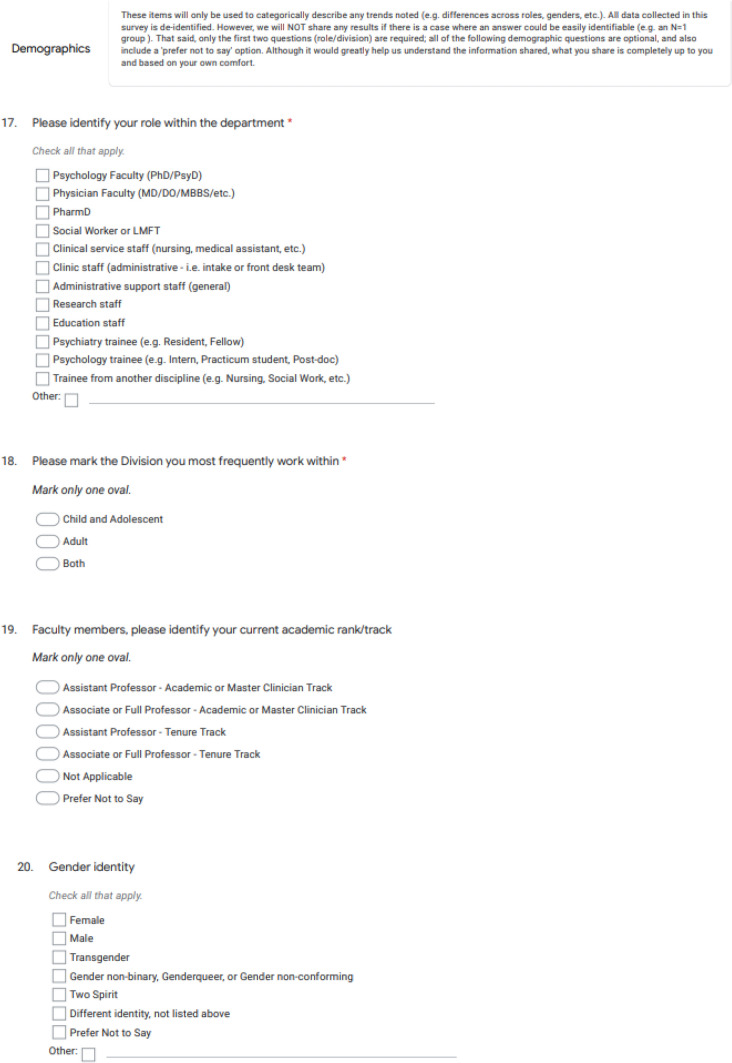

Our initial survey (“Appendix” section) indicated that all areas listed (i.e., sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, race/ethnicity, cultural background, marital/family status, religious/spiritual beliefs, immigration status, age, and disability status) were rated on average as neutral or higher with respect to inclusivity but suggested still room for improvement. It also helped us identify which experiences/identities were rated highest on “welcoming” and which were on the lower end; in subsequent years, we made sure to include efforts focused on those rated lower (e.g., marital/family status, age, immigration status) in addition to topics of ongoing attention (e.g., sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, gender identity). Additionally, our initial survey indicated many felt there needed to be more training on DEI-related topics and a high interest in participation in such training, which we were able to share with department leadership when asking for support for additional opportunities. And as a final example, our survey questions related to recruitment identified areas of need with regard to pulling from more diverse sources for recruitment of faculty, staff, and learners, in order to increase the diversity within department employees.

Qualitative/Mixed Approaches

At each step, it was important for us to gather data both qualitatively and quantitatively. As described previously, qualitative data helps illuminate experiences and uncover themes related to belonging, a sense of feeling welcome, and overall climate for specific diverse sub-groups. Open-ended questions help unmask experiences of oppression or discomfort overlooked by averaging quantitative scores. A “successful” DEI climate is one in which everyone feels valued, accepted, and psychologically safe. Qualitative approaches are also an important way to measure progress on DEI shifts, which may take years to fully emerge. Concrete examples that demonstrate individual and departmental practice and perspective change will help continue support of the work. In the sections below, we provide examples of both questions we asked, and responses received that reflect our combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches.

On-going Evaluation

Assess committee impact for reflection and any needed adjustments. Gathering feedback about the committee itself may feel extraneous, but it is important for the group to understand its own strengths and areas to improve, as well as what is and is not working. One area of our annual survey includes rating the impact of the committee and providing qualitative feedback. Ratings indicated upward trends around the positive impact of the committee on the department. The most informative feedback, however, came from the qualitative comments. Emergent themes included ways in which the committee increased DEI-related awareness, safe spaces (where people felt comfortable showing up authentically), and openness to conversation. Additionally, DEI events and activities, strong leadership, infusion of DEI perspectives into all sectors, and departmental support for the committee were identified as strengths. Opportunities for growth included visibility (e.g., a few new department members noted not being aware there was a committee) and calls for faster progress (which often also came with the acknowledgement that progress in these areas takes time). This information provided an opportunity for reflection on successes and challenges/suggestions for change. Moreover, it made the case to leadership for the continued need for the committee/work.

Include evaluation in each activity or event. We included standard evaluation questions such as asking participants to rate on a Likert scale the effectiveness of the speaker, utility of content, and climate for discussion. We also asked participants to rate their likelihood of making changes in their role/work within the department and asked them to identify specific examples, along with any barriers to or facilitators of that change. Gathering data on barriers to participation helped to inform future approaches/activities. Additionally, questions regarding the impact of the given event on individuals’ practice allowed us to identify short-term impact while long-term effects were still in process. Both process and practice change themes emerged from individual events. For instance, participants identified processes related to self-reflection such as: “becoming more aware of implicit bias and how it affects my work” and “being more mindful of my own hidden biases.” They also noted more concrete plans for practice change such as: “sharing and implementing this information with my learners,” “explicitly calling out biases when I see them,” “utilizing more welcoming language with my learners and colleagues,” “articulating a clear lab policy regarding expectations for equity and communication” and “I have revamped my lectures to include [content from this talk], and “pushing for more inclusive language on our intake forms.”

In our full department events, such as retreats, we asked participants to provide feedback about the utility of the event (e.g., “would you recommend this event to a colleague?”) as well as how well the event met their expectations and how likely they were to make measurable change in their work/role due to attending the event. Knowing that time is always a valued commodity, the results from latter questions were particularly useful in understanding the value participants placed on the event. For instance, 90% of participants or higher (90% in 2018, 97% in 2021) noted they would recommend the retreat to a colleague. Participants also felt that the event met their expectations (85% in 2018 and 97% in 2021 reported ‘very much’ or ‘a lot’). Again, we asked participants to identify specific practice changes and potential barriers to and facilitators of that change. Many of the barriers and facilitators identified across events are detailed in our “Lessons Learned” section, along with implications for DEI work.

Readminister survey to track progress and identify emerging needs. As noted above in Step 3, we utilized an adapted version of the Diversity Engagement Survey to assess departmental climate, personal experiences, and beliefs about recruitment and training. We readministered this survey each year to track progress towards both broad and specific goals. It will be important to consider the ‘Heisenberg Principle’, which in this case means that ratings may actually indicate decreased favorability as awareness of DEI-related topics arise. That is, knowledge leads to closer scrutiny, which may make results appear to demonstrate ‘worsening’, when in fact, it is merely capturing increasing awareness of challenges. The results of the survey over the past three years reflect this very concept in some areas. Overall, results have demonstrated neutral or better ratings across all areas, and slight, but not significant, decreases in “welcoming” ratings for individual identity-based characteristics (e.g., sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, race/ethnicity, cultural background, marital/family status, religious/spiritual beliefs, immigration status, age, disability status). However, it was notable that a more nuanced view of individual ratings allowed us to identify areas that needed more attention based on these ratings as well (e.g., religious/spiritual beliefs, age, disability status).

With regard to diversity climate across the department, we saw a slight increase in nearly every area between Year 1 and 2 (e.g., overall climate, open communication related to DEI, value of DEI competence/sensitivity by the department, respect for a wide range of experiences/views, publicizing DEI principles, and presence of DEI-related materials). Year 3 indicated some minor decreases in ratings across these areas, but the most recent iteration of the survey was administered in June 2020 in order to stay on track with previous years’ timing, but it is notable that the most recent survey administration was just on the heels of the death of George Floyd and significant community unrest in Minneapolis, and so raters may have held a more (justifiably) critical lens with higher levels of scrutiny than they might have even a month earlier. Notably, departmental commitment and commitment of leadership to DEI remained largely consistent across the 3 years. Again, these ratings provided valuable information regarding areas in need of focus (e.g., visibility of diversity principles).

Finally, we assessed individuals’ personal experiences and views related to support of diversity in the department, feeling that one’s comments are valued and respected, and comfort in discussing DEI-related issues in large and small groups. Individuals were also asked about times when they felt they needed to minimize aspects of culture or in which a supervisor or colleague treated them differently due to a diversity-related characteristic. Most of these areas exhibited a great deal of stability across the three years. However, of note, decreases in comfort discussing DEI issues in both large and small groups emerged, with small groups feeling more comfortable. This is an area of further exploration and shaped immediate activities (e.g., providing more small group opportunities for discussion, attention to building safety and acknowledging acceptance of discomfort in DEI discussions). The last areas of focus within the survey were recruitment and training, which both exhibited similar patterns of increase from Year 1 to 2, and some decrease in Year 3. The largest decreases were related to recruitment of faculty, learners, and staff. This indicated an area on which to focus, and in fact was reflected in specific goals set by the department around the time of the survey. Additionally, resources were created to strengthen the strategies for recruitment from a wider range of applicants and sources. On a related note, views on availability of and requirements for training remained stably strong, with increases in views that DEI training should be required for all staff, faculty, and learners. This helped to advocate for protected time for all to attend DEI-focused events such as a departmental retreat.

It is important to be iterative in on-going evaluation of this nature, where we know learning is also on-going. For instance, in the early iterations of the survey, we asked for “other” areas/identities that could be rated for “welcoming.” As a result of early responses, we added more identity characteristics (e.g., body size, socioeconomic status) into later versions of the survey. Similarly, when new terms/concepts (e.g., antiracism) and ideas emerged into popular awareness during 2020, we added targeted questions that asked about knowledge and awareness of antiracism specifically, and DEI topics broadly. We also recognized a gap in the survey based on previous qualitative responses (discussed below) with regard to impact on practice, and thus added inquiries specifically addressing how frequently race or racism are incorporated into work broadly, and specifically for clinical, educational, and research practices. These new questions will allow for more specific information in tracking change over time among department members’ knowledge and practices.

Demographic Data

The annual survey we conduct includes (optional) demographic data. It is important to note that many departments and medical schools lack demographic data on their faculty, staff, and learners. If it is not collected systematically upon enrollment/hiring, demographic data may be difficult to gather later. In some cases, individuals may be hesitant to share information about their identities without clarity on how the information could be used, especially if that information is not visible/obvious (e.g., sexual orientation, gender, immigration status, etc.). Collecting this information as part of the annual survey allows for a more nuanced view of the data (e.g., are there differences across faculty/staff/learners on comfort in DEI discussions, do specific groups feel more or less comfortable in discussion of DEI topics, etc.). It is essential that if departments choose to collect this data it be made clear how the data will be used and that opting out and/or anonymous responses are allowed. Our survey included specific language in both the initial email and the survey that detailed this information (see “Appendix” section).

Lessons Learned

Below are some themes and challenges that we have encountered in implementing this model. Considering these themes may help to preventatively address similar challenges and facilitate successes in DEI work.

Impact of COVID-19 and Racism Pandemics of 2020

The word unprecedented was the descriptive theme for most of 2020. For DEI work, this played out due to both the COVID-19 pandemic and the racism pandemic (APA, 2020) in which BIPOC communities were disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. These societal shifts directly impacted DEI work within medical institutions across the country, as well as in our own institution and department. We detail below some of the shifts in language, perspective, conversation, and practical work that were relevant to DEI efforts, as it is likely these shifts will be markers of permanent changes going forward.

First, the shift to remote work led to increased opportunities for (and acceptability of) virtual trainings and meetings. For the purposes of DEI work, the additional focus on racial injustice following May 2020 also meant an increase in the number and type of training and resources that were made freely available both within and outside of our institutions. The opportunities themselves became more accessible to some, as many were asynchronous and could be joined at times that were convenient for an individual. Virtual meetings also led to an increase in those able to attend meetings for some (i.e., reduction in transit times, ability to join parts of multiple meetings for those overbooked), while it created barriers for others (i.e., technology access, those balancing caregiving and remote work). These increases in access as well as barriers helped to illuminate the very issues on which the DEI Committee was focused.

Ultimately, the largest shift seen in our department was the urgency of conversations about racial and social justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. The increased awareness among department members (and society at large) led to prioritizing DEI work in discussions and work activities. It also propelled forward DEI initiatives that had previously received attention but stalled at the system and institutional levels. Requests for a protocol for providers to address biased or discriminatory comments from patients landed differently, and action was taken. A broader conversation shifted language and action around ‘medical mistrust’ by historically excluded communities towards ‘closing the trust gap,’ placing the responsibility for action at the feet of the institution rather than the marginalized communities. In the department, each sector and division of clinical, research, education work was charged with identifying specific, short-term goals towards bringing the department closer to the goal of becoming allies in policies and action. This charge led to the infusion of DEI conversations into every meeting, group, and conversation, and a commitment to prioritizing this work moving forward.

With disproportionate impacts of the pandemic becoming clearer (e.g., healthcare/COVID-19 disparities among BIPOC communities, productivity metrics disproportionately affecting women and single parents, etc.), calls for more drastic and expeditious change filtered across institutions known for slower change. As mentioned above, the system-level began to shift simultaneously with the addition of the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the Medical School level. The prescient timing of beginning this process in 2019 allowed a home in which some of the growing momentum could land. We elaborate further on some of these issues in the Communication and Collaboration Step of the model.

Considering and Addressing Common Barriers to Engagement/Participation

Below we outline several themes from across 3+ years of work. Although DEI activities and involvement by department members increased, some common barriers to participation persisted. These barriers are not unique to our institution or department, so we highlight a few below in order to share knowledge across groups, and in hopes that colleagues who are beginning the process of DEI work can address some of these topics from the outset.

Time

Historically, DEI work tends to be undertaken by URMs who are most impacted by marginalization or oppression, and often is done on a volunteer basis, which perpetuates the cycle of the “invisible/emotional labor” (Mustapha & Eyssallenne, 2020; Rodríguez, Campbell, & Pololi, 2015). It is important to account for this time as one would for other leadership positions within the institution (i.e., UCLA’s inclusion of DEI statements in promotion/tenure processes, Waugh, 2018). Additionally, individuals in the department may encounter limitations on time and competing responsibilities as barriers. We suggest that committee leadership proactively secure approval from leadership to strongly encourage broad attendance and for department members to prioritize DEI events, particularly for those with clinical caseloads or other administrative responsibilities.

Role

Hierarchical biases may impact participant views or ability to affect change within teams, especially for staff and learners. We recommend making these biases an explicit part of the conversation from the start; begin with faculty and leadership to prepare them for these conversations. It was important to have open discussions in the department to determine appropriate norms. For example, many moves to dismantle hierarchy result in a move to “first-name basis” and decreasing the use of formal titles among colleagues to build collegiality and break down hierarchical barriers. However, in some cases, those who had experience with being overlooked in their roles (e.g., patients assuming a female doctor is the nurse, residents of color assumed not to be the doctor, etc.) may have reason to request the use of titles with patients. It is also important to differentiate ways that practices designed to reduce hierarchy may vary in patient-facing versus non-patient-facing settings.

Connecting with Colleagues

Different physical locations and varied work schedules can limit opportunities to overlap with colleagues and continue DEI conversations. Once interest is sparked, we created formal and informal spaces for building the familiarity and comfort required to engage in deeper conversations. This area is prime for benefit from the discovery of virtual spaces brought on by necessity of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent remote work. While not ideal for deeper conversation and more sensitive discussions, virtual spaces may be used for providing broader content with in-person or smaller group virtual spaces offered for debriefing and follow-up on the presented content.

Funding

Inherent to all of the above items, funding is necessary to provide credit for time as well as compensating speakers and holding events, as described in Step 1. Departmental/institutional commitment of sustainable, on-going funds is essential to the success of DEI work and sends a strong message about the value placed on such work. For instance, monthly meetings can total to a minimum of 12 h per year, but committee work in the intervening weeks can be double or triple that number depending on the activities of the committee. Acknowledging the time and commitment of committee members will likely look differently across departments and institutions, but it is important to note that at minimum it be considered in ‘service’ work. It may also make sense to shift or reassess the ways in which ‘service’ is valued to underscore the importance of DEI work as central to the functioning of the department. Furthermore, an on-going operational budget for the DEI Committee is ideal. While grant funding may be available and is encouraged as a starting point, having a budget line within the overall department planning not only demonstrates commitment from the department leadership, but also allows for sustainability of activities and the work. Specific funding amounts may vary by institution and department but funding from educational or clinical bodies may be requested to support some of the work as well.

Provide and Integrate Tools and Resources

Training/Preparation

Discussions about DEI-related topics are potentially more difficult than typical departmental activities due to the emotional and personal nature of experiences related to DEI, social identity constructs, and the vulnerability of sharing one’s own biases, missteps, and growth. Additionally, inherently, conflict can arise when opposing viewpoints or experiences are present. Groups who are not wholly comfortable voicing or addressing disagreement were given the opportunity to engage in communication skills training related to courageous conversations and/or conflict management. Once an appropriate climate was established, we provided resources for self-education on DEI topics, engaging in challenging/courageous conversations, and healthy and positive conflict resolution skills, made readily available on the department intranet.

Continued Workshops and Activities

We provided on-going opportunities for education and space for continued conversations. We explicitly acknowledge that any one event is intended only as a starting or enhancing point. Workshops included speakers on topics related to equity, diversity, and inclusion (e.g., implicit bias training for search committees, cultural humility training for department members, incorporating conversations about race and racism for healthcare providers, identifying and utilizing non-biased measures in research, culturally competent curriculum development for education-focused individuals, etc.). We organized department-wide activities such as discussion groups or book clubs to provide smaller, more interactive opportunities for department members to engage in deeper, more reflective conversations. These types of activities helped to initiate further actions and integrate DEI work across sectors of the department. For instance, in our department, a book club discussion led to an explicit focus on diversity, identity, and reflections on biases in the departmental case conferences. Similarly, a focus was put on increasing gender equity and historically underrepresented scholars in Grand Rounds speaker invitations after this was identified by the committee as an opportunity.

Work Across Sectors

We offered training tailored to participants' role or sector (e.g., clinical practice/education/research). For example, training on harassment in the clinical learning environment was specifically relevant for those who provide clinical services. Similarly, work to update intake forms may look differently across research versus clinical sectors. Following a broader training, such as those described above, smaller workgroups were established to lead sector-specific DEI activities. We ensured that the leadership was engaged in the learning opportunities and provided opportunities for faculty and staff to learn together across sectors such as research, clinical practice and administration duties within an AHC.

Conclusion

In conclusion, and as noted throughout the discussion above, our model is highly adaptable and is meant to be tailored to individual departments. However, some common themes and steps exist and can serve as a foundation for the deep work of DEI efforts. As departments implement the model, it will be essential to collect and share data about the impacts broadly so that the academic medical community can learn from one another’s successes and challenges in DEI work. By sharing this model, we hope to contribute to a broader learning of how clinical learning environments can benefit from and grow in their equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Dr. Sophia Vinogradov, and the Members of the Department’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee. These dedicated individuals are too numerous to be named individually here, but their commitment and passion were essential in executing the activities described above. The preliminary results shared represent the collective success of an innovative committee of faculty, staff, and learners collaborating on a shared goal and vision.

Appendix: DEI Survey Administered Annually to Department Members

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. Each author took part in drafting the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Some of the events were supported by Internal Small Grants from the University of Minnesota Office of Equity and Diversity (e.g., Campus Climate Microgrants) and the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences (e.g., Disruptive Innovation Projects). These funds were used to compensate training/event speakers for their time and talents.

Data Availability

Not applicable. The only data included in this manuscript is program evaluation data, which is de-identified and not specific to individuals, but rather events.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Katherine A. Lingras, M. Elizabeth Alexander, and Danielle M. Vrieze declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

All authors provide consent to publish this manuscript and its content. No identifying information or specific participant data is provided in this manuscript. An earlier version of some information included in this manuscript was presented at the 2019 and 2021 meetings of the Association for Psychologists in Academic Health Centers (APAHC).

Footnotes

It is well-established that consideration of equity is an essential component of modern-day healthcare. Health inequity also often stems from issues related to diversity and inclusion work (i.e. racism, biases, etc.). While these areas are important to consider, for the purposes of this paper we will focus on the diversity and inclusion components with the understanding that equity is intrinsic in this work but requires its own focus to which we cannot do justice here.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agrawal P, Madsen T, Lall M. Gender disparities in academic emergency medicine: Strategies for the recruitment, retention and promotion of women. AEM Education and Training. 2019;4:S67–S74. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Standards of accreditation in health service psychology. https://www.apa.org/ed/accreditation/about/policies/standards-of-accreditation.pdf.

- American Psychological Association. (2020, May 29). ‘We Are Living in a Racism Pandemic,’ Says APA President (Press release). http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2020/05/racism-pandemic.

- American Psychological Association. (2021, July). Equity, diversity, and inclusion.https://www.apa.org/about/apa/equity-diversity-inclusion.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. (2021, July). Equity, diversity, and inclusion.https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/diversity-inclusion.

- Association of Psychology Postdoctoral and Internship Centers. (2021, July). APPIC diversity statement.https://www.appic.org/About-APPIC/APPIC-Diversity-Statement.

- Borlik MF, Godoy SM, Wadell PM, Petrovic-Dovat L, Cagande CC, Hajirnis A, Bath EP. Women in academic psychiatry: Inequities, barriers, and promising solutions. Academic Psychiatry: THe Journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry. 2021;45:110–119. doi: 10.1007/s40596-020-01389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KM, Rodríguez JE. Addressing the minority tax: Perspectives from two diversity leaders on building minority faculty success in academic medicine. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019;94:1854–1857. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carethers JM. Toward realizing diversity in academic medicine. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2020;130:5626–5628. doi: 10.1172/JCI144527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes M, Handelsman J, Sheridan J. Diversity in academic medicine: The stages of change model. Journal of Women’s Health. 2005;2002(14):471–475. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson TL, Aguilera A, Brown SD, Peña J, Butler A, Dulin A, Jonassaint CR, Riley I, Vanderbom K, Molina KM, Cené CW. A seat at the table: Strategic engagement in service activities for early-career faculty from underrepresented groups in the academy. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019;94:1089–1093. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalyst. (2020). Why diversity and inclusion matter: Quick take. https://www.catalyst.org/research/why-diversity-and-inclusion-matter.

- Chrobot-Mason D, Aramovich NP. The psychological benefits of creating an affirming climate for workplace diversity. Group and Organization Management. 2013;38:659–689. doi: 10.1177/1059601113509835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L, Hall GN, Neville H. Racial trauma: Theory, research, and healing: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist. 2019;74:1–5. doi: 10.1037/amp0000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devakumar D, Selvarajah S, Shannon G, Muraya K, Lasoye S, Corona S, Paradies Y, Abubakar I, Achiume ET. Racism, the public health crisis we can no longer ignore. Lancet. 2020;395:e112–e113. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31371-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz T, Navarro JR, Chen EH. An institutional approach to fostering inclusion and addressing racial bias: Implications for diversity in academic medicine. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2020;32:110–116. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2019.1670665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Social Science and Medicine (1982) 2014;103:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes. (2011). Global diversity and inclusion fostering innovation through a diverse workforce. https://www.forbes.com/forbesinsights/StudyPDFs/Innovation_Through_Diversity.pdf.

- Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2019;111:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DM, II, Joseph JJ, Glover AR, Olayiwola JN. How academia should respond to racism. Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2020;17:589–590. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting black lives—The role of health professionals. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375:2113–2115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1609535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman RR, Murphy KA, Karbeah J, Kozhimannil KB. Naming institutionalized racism in the public health literature: A systematic literature review. Public Health Reports. 2018;133:240–249. doi: 10.1177/0033354918760574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman RR, Przedworski JM, Burke S, Burgess DJ, Perry S, Phelan S, Dovidio JF, van Ryn M. Association between perceived medical school diversity climate and change in depressive symptoms among medical students: A report from the medical student change study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2016;108:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KA, Jones D, Woodworth L. Physician–patient race-match reduces patient mortality. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3211276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KA, Samuels EA, Gross CP, Desai MM, Sitkin Zelin N, Latimore D, Huot SJ, Cramer LD, Wong AH, Boatright D. Assessment of the prevalence of medical student mistreatment by sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020;180:653–665. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holvino E, Ferdman BM, Merrill-Sands D. Creating and sustaining diversity and inclusion in organizations: Strategies and approaches. In: Stockdale MS, Crosby FJ, editors. The psychology and management of workplace diversity. Blackwell Publishing; 2004. pp. 245–276. [Google Scholar]

- Hong L, Page SE. Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:16385–16389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403723101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the U.S. Healthcare Workforce, Smedley, B. D., Stith Butler, A., & Bristow, L. R. (Eds.) (2004). In the nation's compelling interest: Ensuring diversity in the health-care workforce. National Academies Press (US). [PubMed]

- Kim SE, Kim N, Park YS, Kim EY, Park SJ, Shim KN, Choi YJ, Gwak GY, Park SM. Importance of a diversity committee in advancing the Korean Society of Gastroenterology: A survey analysis. The Korean Journal of Gastroenterology = Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe Chi. 2019;74:149–158. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2019.74.3.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, S. R. (2020). Diversity confirmed to boost innovation and financial results. Forbes.https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesinsights/2020/01/15/diversity-confirmed-to-boost-innovation-and-financial-results/?sh=5655c0e0c4a6.

- Lu DW, Pierce A, Jauregui J, Heron S, Lall MD, Mitzman J, McCarthy DM, Hartman ND, Strout TD. Academic emergency medicine faculty experiences with racial and sexual orientation discrimination. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020;21:1160–1169. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.6.47123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks LM, Herzer KR. Prevalence of self-disclosed disability among medical students in us allopathic medical schools. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2016;316:2271–2272. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks, L., & Jain, N. (2018). Accessibility, inclusion, and action in medical education: Lived experiences of learners and physicians with disabilities. Association of American Medical College. https://sds.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra2986/f/aamc-ucsf-disability-special-report-accessible.pdf.

- Meeks L, Neal-Boylan L. Disability as diversity a guidebook for inclusion in medicine, nursing, and the health professions: A guidebook for inclusion in medicine, nursing, and the health professions. Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morse M, Loscalzo J. Creating real change at academic medical centers—How social movements can be timely catalysts. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383:199–201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2002502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustapha T, Eyssallenne T. Paying a penny for our thoughts and then asking for our 2 cents. Academic Medicine. 2020;95:1788. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nivet MA, Taylor VS, Butts GC, Strelnick AH, Herbert-Carter J, Fry-Johnson YW, Smith QT, Rust G, Kondwani K. Diversity in academic medicine no. 1 case for minority faculty development today. The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2008;75:491–498. doi: 10.1002/msj.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page S. The diversity bonus: How great teams pay off in the knowledge economy. Princeton University Press. 2017 doi: 10.2307/j.ctvc77c0h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul-Emile K, Critchfield JM, Wheeler M, de Bourmont S, Fernandez A. Addressing patient bias toward health care workers: Recommendations for medical centers. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020;173:468–473. doi: 10.7326/M20-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, D., Person, S. D., Fink, O. L. M., Jordan, C. G., Allison, J. J., Castillo-Page, L., & Schoolcraft, S. (2012) Diversity engagement survey, user guide. University of Massachusetts.

- Pololi L, Cooper LA, Carr P. Race, disadvantage and faculty experiences in academic medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:1363–1369. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1478-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pololi LH, Krupat E, Civian JT, Ash AS, Brennan RT. Why are a quarter of faculty considering leaving academic medicine? A study of their perceptions of institutional culture and intentions to leave at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Academic Medicine. 2012;87:859–869. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182582b18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price EG, Gozu A, Kern DE, Powe NR, Wand GS, Golden S, Cooper LA. The role of cultural diversity climate in recruitment, promotion, and retention of faculty in academic medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:565–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price EG, Powe NR, Kern DE, Golden SH, Wand GS, Cooper LA. Improving the diversity climate in academic medicine: Faculty perceptions as a catalyst for institutional change. Academic Medicine. 2009;84:95–105. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181900f29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Clark LW, Jo AW, Cruvinel E, Durham D, Shaw P, Shih G, Befort CA, Simari RD. Women physicians and promotion in academic medicine. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383:2148–2157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1916935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson QM. Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations. Group and Organization Management. 2006;31:212–236. doi: 10.1177/1059601104273064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez J, Campbell K, Pololi L. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: What of the minority tax? BMC Medical Education. 2015;15:6. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena A. Workforce diversity: A key to improve productivity. Procedia Economics and Finance. 2014;11:76–85. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00178-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shore LM, Randel AE, Chung BG, Dean MA, Holcombe Ehrhart K, Singh G. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management. 2011;37:1262–1289. doi: 10.1177/0149206310385943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DG. Building institutional capacity for diversity and inclusion in academic medicine. Academic Medicine. 2012;87:1511–1515. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826d30d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society of Clinical Psychology. (2021, July). Diversity Committee. https://div12.org/diversity/.

- Sotto-Santiago S, Mac J, Duncan F, Smith J. “I didn't know what to say”: Responding to racism, discrimination, and microaggressions with the OWTFD approach. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10971. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan TQ. Principles of inclusion, diversity, access, and equity. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019;220:S30–S32. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanPuymbrouck L, Friedman C, Feldner H. Explicit and implicit disability attitudes of healthcare providers. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2020;65:101–112. doi: 10.1037/rep0000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas EA, Brassel ST, Perumalswami CR, Johnson T, Jagsi R, Cortina LM, Settles IH. Incidence and group comparisons of harassment based on gender, LGBTQ+ identity, and race at an academic medical center. Journal of Women's Health. 2020 doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, S. L. (2018). New EDI statement requirement for regular rank faculty searchers. UCLA Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion.https://equity.ucla.edu/news-and-events/new-edi-statement-requirement-for-regular-rank-faculty-searches/.

- Wright JL, Jarvis JN, Pachter LM, Walker-Harding LR. “Racism as a public health issue” APS racism series: At the intersection of equity, science, and social justice. Pediatric Research. 2020;88:696–698. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-01141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. The only data included in this manuscript is program evaluation data, which is de-identified and not specific to individuals, but rather events.

Not applicable.