Abstract

Tobacco use contributes to more mortality and morbidity globally than any other behavioral risk factor. Adverse effects do not spare the oral cavity, with many oral diseases more common, and treatments less successful, in the tobacco-using patient. Many of the oral health effects of cigarette smoking are well-established, but other forms of tobacco, including cigars and smokeless tobacco, merit dental professionals’ attention. Recently, an expanding variety of new or emerging tobacco and/or nicotine products has been brought to market, most prominently electronic cigarettes, but also including heated tobacco and other noncombustible nicotine products. The use of cannabis (marijuana) is increasing and also has risks for oral health and dental treatment. For the practicing periodontist, and all dental professionals, providing sound patient recommendations requires knowledge of the general and oral health implications associated with this wide range of tobacco and nicotine products and cannabis. This review provides an overview of selected tobacco and nicotine products with an emphasis on their implications for periodontal disease risk and clinical management. Also presented are strategies for tobacco use counselling and cessation support that dental professionals can implement in practice.

Tobacco use is responsible for nearly 9 million annual global deaths (approximately 15% of all deaths worldwide) -- more than any other behavioral risk factor and trailing only high systolic blood pressure among all risk factors in its contribution to human mortality.1 Tobacco smoke disrupts the functioning of nearly every human organ system, causing most deaths through cancer, heart disease, and non-cancer respiratory diseases.2 Health risks extend not only to the person using tobacco but to people involuntarily exposed to smoke (second-hand smoking).3 Tobacco experimentation typically begins in adolescence, often due to both social influences and tobacco marketing.4 Later in life, most adult tobacco users find themselves chemically and/or behaviorally dependent on nicotine and unable to quit tobacco use.2 Yet, despite this well-chronicled destruction, industrially produced tobacco products remain legally sold and marketed in nearly every country, well surpassing $1 trillion (United States dollars) in annual sales.

Owing to combined efforts of public messaging, excise taxes, social norm shifting, and numerous other tobacco control strategies, cigarette smoking prevalence in most high-income countries has declined dramatically in recent decades.2,5–8 However, as the current number of global deaths would indicate, substantial challenges remain. China, by far, is the single largest consumer of cigarettes and where smoking prevalence, especially among men, remains persistently high.9 While smoking prevalence in Africa has historically been low, aggressive tobacco industry efforts on the continent have health experts projecting increased tobacco use over the coming decades.10 In countries where smoking prevalence has declined, inequalities in tobacco use and cessation have often risen, marked by widened gaps according to socioeconomic disadvantage,11,12 race/ethnicity,12 and mental illness,13 among other factors, exacerbating health inequity.

The most recent decade has also seen an expanding variety of new or emerging tobacco and/or nicotine products brought to market, most prominently electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). Heated tobacco products14 and nicotine-containing pouches15 are other examples of an increasingly diverse product landscape. Meanwhile, more permissive laws and regulations have broadened access to cannabis (marijuana) products. Cannabis, while not a tobacco product, is frequently consumed in combination with tobacco and by individuals who also use tobacco.16,17 Smoke from cannabis products shares many chemical properties with tobacco smoke and has been linked to health problems, including potential cardiovascular18 and respiratory19,20 impairment.

For the practicing clinician, providing sound patient recommendations requires knowledge of the general and oral health implications not only associated with smoking cigarettes but with cannabis and the wide range of currently available tobacco and nicotine products. Personalized, empathetic patient communication in the dental setting can enhance patients’ motivation to quit tobacco use, and patients willing to make a quit attempt must be connected with evidence-based resources and support to achieve this tobacco-free goal. This review will provide an overview of selected tobacco and nicotine products with an emphasis on implications for periodontal disease risk and clinical management. Also presented will be strategies for tobacco use counselling and cessation support that dental professionals can readily implement in practice.

Cigarettes

Cigarette smoking elevates the risk of nearly every oral condition that dental professionals are tasked with treating and diminishes the chances of many dental treatments being successful.21–23 Cigarette smoking is strongly associated with heightened risk of cancer of the oral cavity or pharynx,21,24–26 with evidence supporting a dose-response relationship27 and synergistic risk with alcohol consumption.24,28 In countries where use of chewing tobacco is uncommon, most oral cancer cases are attributable to tobacco smoking,29,30 with human papilloma virus infection a growing contributor.31 Apart from gingival and periodontal conditions, associations have also been reported between cigarette smoking and dental caries32 and oral pain,33 with an altered oral microbiome and diminished salivary flow proposed as potential mechanisms, but with less causal certainty for these outcomes.23,34

The destructive impact of tobacco smoke on gingival tissues was formally reported as early as the mid-19th Century.35 Over the following 125 years, multiple clinical and population studies had demonstrated strong associations between cigarette smoking and gingival disease,36–38 diminished epithelial attachment and alveolar bone height,39,40 and tooth loss.41 These studies generally also noted greater levels of plaque and calculus accumulation among smokers,36,38–40,42 leading to some academic debate at the time over whether smoking and periodontal disease associations reflected merely poor oral hygiene practices among smokers or a causal contribution of the tobacco exposure itself.40,43 More recent investigations support a causal role, with large representative patient-based and population-based studies confirming a strong, consistent association of smoking with worse periodontal status,44–48 including independently of dental plaque levels and other plausible confounders, such as age, sex, and socioeconomic position.44,49–52 These associations persist in prospective longitudinal analyses demonstrating that cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for losing periodontal support over time53–56 and eventual loss of teeth.57–59

Laboratory-based and clinical studies offer insight to potential mechanisms of action, providing evidence that tobacco smoke exposure impairs the protective host response to the dental plaque biofilm while additionally heightening the production of potentially destructive inflammatory cytokines and enzymes.60,61 Furthermore, distinct microbial patterns between the plaque biofilm of tobacco smokers and non-smokers have been characterized, suggesting a more pathogenic profile.62,63 The gingival vascular response to plaque bacteria is impeded in tobacco smokers via mechanisms still under study but that may include suppressed angiogenesis or vasoactive smoke constituents.64 Finally, tobacco smoking appears to diminish the reparative capacity of periodontal cells, including fibroblasts, osteoblasts and cementoblasts, reducing the ability to form new tissue and potentially impeding responsiveness to periodontal therapy.65,66 While whole tobacco smoke is clearly damaging to oral cells and tissues, deciphering which of the many components of tobacco smoke are most responsible for these effects is challenging. A recent review of the in vitro evidence concluded that nicotine, the highly addictive chemical, was alone unlikely to be cytotoxic to oral tissues at physiological levels.67

Implications for the practicing clinician go beyond the need to expect a higher occurrence of adverse periodontal conditions among cigarette smoking patients. The predictability and overall success of periodontal treatments will be lessened among tobacco smoking patients.68,69 Smoking is associated with worse outcomes following non-surgical debridement,70–72 open surgical debridement,73,74 bone grafts,75 guided tissue regeneration,76 and periodontal plastic surgery.77 Smoking is similarly a risk factor for dental implant failure.78,79 The clinician must identify and document the tobacco use status of all patients. While tobacco use is not a contraindication for providing surgical or non-surgical periodontal therapy, patients must be informed of the elevated risk of less favorable treatment outcomes. This conversation should be embraced as an opportunity to assess -- and enhance -- the patient’s motivation to quit smoking and for the clinician to fulfill a professional responsibility to provide supportive, empathetic advice to quit and connect the patient with evidence-based tobacco cessation support, as discussed in a later section of this review.

Smokeless (Spit) Tobacco

The term smokeless tobacco has been used to cover a wide variety of noncombustible tobacco products that are held in the mouth or chewed.80 This includes areca nut products, such as betel quid (paan), gutka, and mainpuri in South and Southeast Asia, where the consumption of these and similar products has been strongly associated with oral cancer.80,81 These smokeless products contain high levels of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, believed to be highly carcinogenic,82 in contrast to low-nitrosamine snus products consumed in Sweden, which most existing epidemiologic studies have not associated with oral cancer.80,82 In the United States, oral moist snuff is the predominant form of smokeless tobacco used,83 more often among younger men in rural communities.84 In 2017, the United States Food and Drug Administration estimated that a product standard to mandate low nitrosamine content in United States smokeless tobacco products would prevent 12,700 cases of oral cancer over 20 years;85 however, the proposed standard was not implemented. Other health effects linked to smokeless tobacco use include cancers of the esophagus and pancreas, and plausibly, but less conclusively, adverse cardiovascular outcomes and cancers of the lung and cervix.80

Among non-cancer oral health conditions associated with use of moist snuff or chewing tobacco, oral mucosal lesions, including hyperkeratotic or erythroplakic lesions, are commonly found even among young users.86–89 Gingival recession and periodontal attachment loss have been reported near the areas where smokeless tobacco is held in the mouth,86,87 as well as dental erosion and gingival recession.88,89 A positive association with severe active periodontal disease was found in the large, representative National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the United States.90 For the dental professional, assessing smokeless tobacco use status and offering cessation support tailored to quitting smokeless products is a critical component of care and may help patients successfully quit.91

Cigars and Pipes

Relative to cigarettes, fewer studies evaluate periodontal health outcomes associated with use of other combustible tobacco products. However, given similarities in the toxicological profiles of cigarette and cigar smoke,92 it is reasonable to expect adverse oral health effects. In the US, cigars are the most used non-cigarette product among adults (4% prevalence) and among young adults aged 18–24 years, use prevalence is more than 3-fold higher (14%).93,94 Dental professionals must ask their patients about all forms of tobacco use and be particularly mindful that the oral health risks of any combustible products are likely to resemble those of cigarette smoking.

A longitudinal evaluation of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging found that cigar and/or pipe users had more missing teeth and more sites with severe loss of attachment and advanced recession compared to non-smokers.95 Another longitudinal study evaluated tooth loss risk and alveolar bone loss in cigar and pipe smokers.96 These authors reported that cigar and pipe users were at a higher risk of tooth loss compared to non-smokers and that more calculus and interdental bone loss were observed in cigar and pipe users than non-smokers.96 An earlier cross-sectional analysis of this same male veteran population in the United States had reported greater accumulation of plaque and calculus in cigar/pipe smokers compared to non-smokers after adjusting for age.97 However, when compared to cigarette smokers, cigar/pipe users had lower accumulation of plaque and calculus and less alveolar bone loss.97 These studies were limited to older, male, predominantly white populations and often grouped cigar and pipe users together. Two nationally representative (United States) cross-sectional studies have considered exclusive groups of cigar and pipe users. In the first, more severe periodontal disease was observed among cigar smokers compared to non-smokers but small sample sizes precluded a detectable difference between cigar and cigarette users.98 More recently, cigar product users and pipe users were both at higher odds of self-reporting gum disease diagnosis and treatment when compared to non-tobacco users.99 To our knowledge, no studies have examined possible differences in oral health effects by type of cigar, such as premium cigars versus cigarillos or cigarette-like small cigars.

Hookah

Use of hookah, also referred to as tobacco waterpipe or narghile, dates back several centuries and is a cultural norm in many countries of North Africa and the Middle East. In other parts of the world, the popularity of hookah has recently increased, particularly among youth and young adults.100–102 Often perceived as less harmful than cigarette smoking,100 hookah smoke contains levels of volatile organic compounds, ultrafine particles, nicotine, and carbon monoxide matching or exceeding cigarette smoke.103,104 Epidemiologic studies have associated hookah use with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.105

Several cross-sectional studies compare periodontal and peri-implant health of hookah smokers with both cigarette smokers and non-smokers. One study found higher plaque index, increased bleeding on probing, and more sites with attachment loss and probing depth >3mm in hookah users compared to non-smokers, with no difference in these parameters between hookah users and cigarette smokers.106 Another evaluation similarly identified greater marginal bone loss and more missing teeth among hookah users compared to non-smokers and reported comparable periodontal status between hookah and cigarette smokers.107 In a third study, increased periodontal bone loss and greater prevalence of vertical bone defects were found in hookah users compared to non-smokers.108,109 Few studies have evaluated peri-implant health in hookah users. A recent review of case-control studies reported worse peri-implant inflammatory parameters and more implant sites with deep probing depths, bleeding on probing, and peri-implant bone loss among hookah users compared to non-smokers.110

Nearly all of the above research was conducted in Saudi Arabia, where use patterns and the hookah product itself might differ from the rest of the world, limiting generalizability. In countries where hookah use is often infrequent and primarily a behavior of young adults, there is a dearth of research evaluating periodontal health outcomes. In one cross-sectional evaluation in the US, hookah use was observed almost exclusively among younger people, who self-reported gum disease at a similar prevalence as tobacco never users.99

Cannabis

A decades-long trend in several countries has seen increasingly liberalizing laws and attitudes around the use of cannabis (marijuana) products for medicinal and recreation use. With policies favoring decriminalization and creation of legal commercial marketplaces, use of cannabis products has risen. Cannabis is the most commonly used recreational drug worldwide after tobacco and alcohol.111 In the United States, 46% of residents aged 12 years and older reported lifetime cannabis use in 2019,112 with the largest increases in current use observed among older adults.113 Given the high use prevalence, frequent consumption in combination with tobacco and/or by individuals who also use tobacco,17 and potential for periodontal harm from cannabis smoke itself,114 the practicing clinician should anticipate encountering cannabis-using patients on a regular basis and be prepared to manage potential oral and periodontal complications.

A limited number of epidemiological studies evaluate the association between cannabis use and periodontitis. Using data from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study birth cohort in New Zealand, cannabis use measured between ages 18–26 was associated with greater odds of experiencing 3mm or more clinical attachment loss between ages 26 and 32, including after controlling for tobacco use and other sociodemographic and behavioral risk factors.115 Following this same cohort to age 38 confirmed the positive association between cannabis use and declining periodontal health.116 Using data the from Aboriginal Birth Cohort study in Australia, investigators examined the prevalence of periodontitis among young adults (mean age: 18 years).117 Almost all cannabis users also used tobacco, precluding an assessment of cannabis-only use on periodontal outcomes; however, among tobacco users, co-use with cannabis was associated with a higher prevalence of periodontal disease.117 In contrast, a cross-sectional study evaluating the presence of periodontal disease in Chilean adolescents did not identify an association between cannabis use and clinical attachment loss.118 Most of the evidence summarized above draws on observations made about youth and young adults, among whom severe periodontal disease is less prevalent. Among adults aged 40–70 in Puerto Rico, frequent cannabis use was associated with prevalent severe periodontitis.119 In one nationally representative study (United States) of adults aged 30 and older, both the mean number of deep pockets and mean clinical attachment loss were higher among frequent cannabis users compared to non-users.120 Even when this analysis was restricted only to tobacco never users, the odds of severe periodontitis were approximately double among frequent cannabis users.120

The potential connections between cannabis use and other oral health conditions are less well studied. Associations have been reported with gingival hyperplasia, xerostomia, leukoedema, and oral infections.114,121 While smoking remains the most common route of cannabis administration, a growing proportion of people consume cannabis as edible products or using vaporizers to produce an inhalable aerosol.122 It is not known how or whether these other routes of cannabis administration relate to periodontal diseases.

For the dental professional, caring for the cannabis-using patient involves more than asking all patients about use and advising non-judgmentally about potential periodontal disease risks. For instance, post-operative instructions should clearly implicate cannabis smoke in addition to tobacco smoke as potential risk factors for complications following intraoral surgeries. When patients attend appointments currently under the influence of cannabis, there are several issues for the dental professional to consider. Due to the altered mental state the provider may judge that the patient does not have capacity to consent for treatment and it may be best to postpone treatment, if possible. Additionally, epinephrine in local anesthetic solutions may trigger a serious tachycardic event in cannabis intoxicated patients.114,123 While some patients might self-medicate with cannabis to address dental pain or appointment-related anxiety, the patient under the influence of cannabis may experience heightened anxiety and dysphoria during a dental visit.114 Therefore, a discussion about cannabis with patients prior to scheduling any surgical procedures can help to avoid potential risks and complications related to managing a patient under the influence of a psychoactive drug.

Electronic Cigarettes and Other Novel Products

For many decades it has been understood that most of the harms from tobacco use come from the combustion process and the resultant complex cocktail of ingredients, and not from nicotine, the highly addictive chemical. Developing alternative ways of delivering nicotine is not a new pursuit; there are a wide array of nicotine replacement therapies that have been used to aide tobacco cessation in a medicalized context for over 30 years.124 The concept of electronic cigarettes, commonly called e-cigarettes, was first patented in the 1960s125 but their use has only become widespread over the last decade. E-cigarettes represent a class of battery-powered products that heat a liquid solution, typically containing nicotine, into an inhalable aerosol.126 E-cigarettes were not developed through the medical pharmaceutical route and are usually considered a consumer product, similar to tobacco products or, in some regulatory contexts, classified as tobacco products.127 Although commercial availability and promotion is potentially part of the appeal of these products, there have been many challenges around regulation, product quality, product perceptions, and limited supporting scientific evidence.

E-cigarettes have undergone substantial evolution over the past decade and can vary widely in appearance and attributes. However, some common features are that they are usually rechargeable, often come as refillable “tanks” or pre-filled “pods,” and in a range of flavors and nicotine strengths. The e-cigarette is usually filled with a liquid that has three main components: a carrier solution (propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin), nicotine (unless nicotine free versions) and flavorings.

Recent clinical trials suggest that e-cigarettes may be effective cigarette cessation aides: outperforming conventional nicotine replacement therapy in two trials when used in combination with cessation counseling.128,129 Epidemiological data from England have shown an increase in overall tobacco quit rates and quit success as the prevalence of e-cigarette use among smokers has increased.130 However, this is not a universal picture, as cohort analyses from the United States have reported no improvement in smoking abstinence with e-cigarette use.131,132 The proportion of smokers who quit by using e-cigarettes who then remain long-term users of e-cigarettes remains an open question.133 E-cigarettes are sometimes presented as a less-harmful alternative for nicotine-dependent tobacco smokers unwilling or unable to cease nicotine use, because the products deliver much lower levels of toxicants relative to cigarette smoke.134,135

However, important concerns surrounding e-cigarettes include rising use prevalence among youth and young adults,136 potential risks for cardiovascular and lung health,137–139 and questions about cessation effectiveness outside clinical trials. The uncertainty and complexity of what impact widespread e-cigarette availability has had, and will have, on public health has spurred much controversy and policy debate.

Given the well-established effect of tobacco smoke on the periodontium and the oral mucosa, it is important to understand the effects of e-cigarette aerosol which also passes in close proximity to these tissues. Research in this field is still emerging and there are many challenges with conducting and interpreting these studies (e.g., often e-cigarette users are recent or current tobacco smokers, meaning it is hard to attribute effects to e-cigarette use directly). Additionally, product evolution has often outpaced research, and the chronic and long-term pathophysiology of periodontitis means that effects could take several years to manifest. It has proven difficult to translate the results of in vitro experiments, some of which report harm to oral-derived cells from e-cigarette aerosols,140 into clinically relevant exposure doses and outcomes. For clinical and population-based studies, separating any effect of current e-cigarette use from those of past or concurrent combustible tobacco use presents another challenge. Among existing findings, exposure to e-cigarette aerosol appears to induce potentially adverse changes in the oral microbiome distinct from those observed with cigarette smoking.141,142 Clinical studies have been largely cross-sectional and sometimes measured oral health conditions as ancillary outcomes to studies outside dental settings. They have reported associations with a wide range of conditions, including throat irritation, gingival bleeding, and oral trauma from exploded e-cigarette devices.140 Population-based studies have largely been confined to self-reported outcomes and cross-sectional designs, with some reporting associations between e-cigarette use and prevalent oral conditions,99,143 but a need exists for additional well-controlled, prospective data.

Doubtlessly, more research is required to understand the extent to which e-cigarettes may independently affect oral health. For the clinician, asking patients specifically about e-cigarettes must be part of recording tobacco use history. The patient deserves a balanced description of the potential risks of e-cigarettes, as well as their potential as a less harmful alternative to combustible tobacco. The tobacco-smoking patient motivated to try e-cigarettes as a cessation aide should not be discouraged from the quit attempt but should also be presented with a menu of evidence-based cessation strategies, as described in an upcoming section. Youth and tobacco non-users should be encouraged not to engage in e-cigarette use. For youth particularly, nicotine exposure may adversely affect adolescent brain development and risk of long-term nicotine dependence.144

E-cigarettes are not the only class of recently introduced products that deliver nicotine without combustion. Newly formulated heated tobacco products create an inhalable aerosol by heating tobacco-containing material to a temperature below the combustion threshold and are reported by their manufacturers to deliver lower levels of harmful chemicals than conventional cigarettes.145 At least one clinical trial, sponsored by a heated tobacco product manufacturer, has announced plans to assess potential periodontal effects.146 Nicotine pouches have been introduced by large tobacco manufacturers as a “tobacco-free” portioned, flavored oral nicotine product.15 Novel nicotine lozenges, gums, mints, and even nicotine-infused toothpicks may resemble nicotine replacement therapies but are not marketed for cessation. Limited evidence exists on which to evaluate the overall health implications of these novel products, let alone possible effects on oral health. While plausibly delivering a less harmful toxicant profile than combustible tobacco, reducing harm to the user is dependent on using these novel products as a substitute for, rather than complement to, cigarette smoking, which may not match the real-world use profile.147

Tobacco Cessation Interventions for Periodontal Patients

The Role of Dental Professionals in Tobacco Cessation

Dental professionals are well-positioned to provide tobacco cessation treatment to their patients. Not only do dental professionals see a large number of tobacco users, but they often have more time with patients and see patients more regularly than other health professionals.148 In addition, the negative health effects of tobacco use are often first identified in the oral cavity, underscoring the importance of managing tobacco-related risk factors for the dental professional. In a systematic review, it was found that tobacco cessation interventions by dentists and dental hygienists during oral examinations can increase cessation among cigarette smokers and smokeless tobacco users.149 Multiple dental professional organizations not only promote tobacco cessation in dental practice but characterize it as a professional responsibility to provide tobacco cessation treatment and education to patients.150–152

Despite their important role in tobacco cessation, dental professionals often fall behind other health professions in providing such care. For example, in a study of health professionals, 80% of dentist and dental hygienist reported asking patients about their tobacco use, but less than 40% reported providing assistance to patients or referring them to cessation programs.153 In another national study of United States dentists, over 90% of respondents reported asking patients about tobacco use, but only 45% reported routinely offering assistance, including referring patients to cessation counseling and/or prescribing cessation medication.154 Similar patterns were seen in a survey of United Kingdom dental professionals, with 79% reporting they “always” enquired about the smoking status of their patients and 77% offering advice.155 While most dentists and dental hygienists report asking patients about cigarette smoking, inquiry about non-cigarette products, such as cigars, hookah, e-cigarette, or cannabis is much less common.156,157 As use of alternative tobacco products increases, dental professionals must ask about use of all tobacco, nicotine, and cannabis products when reviewing a patient’s health history to address fully the risks of long-term use and potential negative oral and systemic health consequences.

Interventions for Tobacco Cessation in Practice

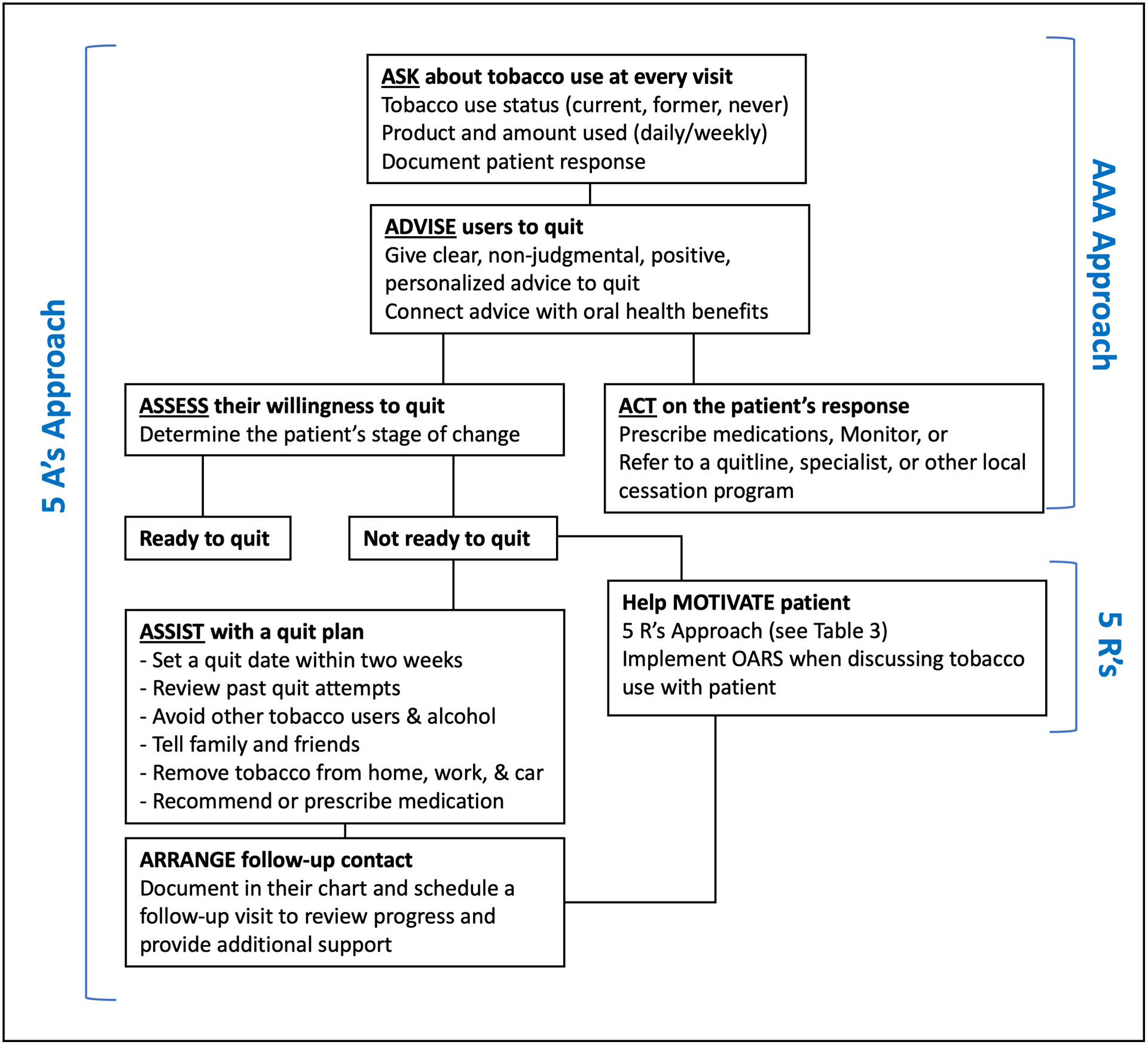

The 5 A’s approach to tobacco cessation (Figure 1) is an evidence-based intervention supported by several countries and organizations, including in the United States,158 Canada,159 Australia,160 and the World Health Organization.148 This intervention involves all members of the dental team and can be incorporated as a standard of practice in dental settings.

Figure 1. Key steps in the 5 A’s and AAA Models for Tobacco Cessation.

Figure 1 depicts two models for organizing the approach to providing tobacco cessation support in a clinical setting: the 5A’s Model (which involves the action steps ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange) and the AAA Model (which involves the action steps of ask, advise, and act). The 5R’s approach is used to frame a motivation-enhancing conversation with a patient not yet ready to quit tobacco use.

Abbreviation: OARS = open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries

The first step of the 5 A’s approach is systematically Asking all patients age 12 years and older about current and former tobacco use. This involves screening patients at every encounter for use of all tobacco products, including related products like e-cigarettes and cannabis. All adolescent patients (age 12–18 years) should be advised not to use tobacco or nicotine. Information obtained from the patient about tobacco, nicotine, and cannabis use should be documented in the patient’s dental chart or health record.

Once tobacco use is identified, the next step is Advising patients to quit. This message should be clear, strong, non-judgmental, and personalized. Advice can be personalized by linking the patient’s tobacco use to health concerns or certain social factors. For example, a person with young children or grandchildren may be motivated by concerns over exposing others to smoke, while a person with periodontal disease may be concerned with the long-term effects on their oral health. In some cases, it may be useful to ask a patient what they do not like about their tobacco use, in order to identify personal factors that may motivate them to consider quitting.148

After advising a patient to quit, the dental professional must then Assess a patient’s readiness to quit. For many patients, quitting tobacco use is a recurring process and readiness to quit will change over time. This process is known as the trans-theoretical model or behavior change model,161 which involves five discrete stages of behavioral change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance (Table 1). It is important to recognize that not all patients have the same level of commitment or readiness to quit. Dental professionals must “meet a patient where they are” in their stage of change in order to support that patient properly in taking action. Therefore, the goal for providers at each appointment will vary based on the patient’s stage of change (Table 1). For example, a patient in the pre-contemplation phase may be resistant to discussing quitting at all. Similarly, a patient in the contemplation phase, may not be ready to choose a quit date or develop a quit plan.

Table 1.

The Behavioral Change Model for Tobacco Cessation

| Stage | Description | Goal for Dental Professionals |

|---|---|---|

| Precontemplation |

|

|

| Contemplation |

|

|

| Preparation |

|

|

| Action |

|

|

| Maintenance |

|

|

Abbreviations: 5 R’s = relevance of quitting, risks of tobacco use, rewards of quitting, roadblocks to successfully quitting, and repetition; OARS = open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries

Adapted from Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47(9):1102–1114.

For patients not ready to quit (typically in the pre-contemplation and contemplation phase), the goal should be focused on enhancing motivation. This can be done by utilizing motivational interviewing techniques. Miller and Rollnick,162 suggest that providers use open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries (a technique known as OARS) when discussing tobacco use with their patients (Table 2). Using such strategies helps dental professionals guide the conversation while allowing the patient to draw on their own intrinsic motivation for change. Another widely recommended approach to enhance motivation is the 5R’s Model,158 which involves discussing: the relevance of quitting, the risks of tobacco use, the rewards of quitting, the roadblocks to successfully quitting, and repetition of motivational strategies at each visit (Table 3). Patients who remain not ready to quit should be encouraged to consider quitting in the future. Providers should document all discussions in the patient’s chart and ask about their tobacco use at each future appointment, being mindful of each patients’ preferences and needs.163

Table 2.

Motivational Interviewing Methods for Tobacco-Using Patients

| Approach | Suggested Actions and/or Language |

|---|---|

|

Open-ended questions Patient benefits Allows patients to express themselves Patients verbalize what is important to them Provider benefits Learn more about the patient Sets a positive tone for the session |

|

|

Affirmations Statements of appreciation to nurture strengths Strategically designed to anchor clients in their strengths, values, and resources despite difficulties/ challenges Authentic observations about the person Focused on non‐problem areas Focused on behaviors vs. attitudes/goals |

|

|

Reflections Reflections from the provider convey: That they are interested in That it’s important to understand the patient The they want to hear more What the patient says is important |

|

|

Summaries Reflecting elements that will aid the patient in moving forward Selective judgement on what to include and exclude Can be used to gather more information Can be used to move into a new direction Can be used to link both sides of ambivalence |

|

Adapted from Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford press; 2012.

Table 3.

The 5 R’s Approach to Tobacco Cessation Counseling

| Approach | Actions |

|---|---|

| Relevance |

|

| Risks |

|

| Rewards |

|

| Roadblocks |

|

| Repetition |

|

Adapted from 2008 PHS Guideline Update Panel Liaisons and Staff. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline executive summary. Respir Care. 2008;53(9):1217–1222.

World Health Organization. Toolkit for oral health professionals to deliver brief tobacco interventions in primary care. In. Geneva: Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; 2017.

When a patient is ready or willing to make a quit attempt, dental professionals can Assist the patient by helping develop a quit plan, discussing cessation medications, and providing or referring the patient for additional tobacco cessation support. Developing a quit plan should involve setting a quit date (ideally, within 2 to 4 weeks), informing family and friends about quitting and asking for their support, anticipating challenges, such as withdrawal symptoms or triggers, and removing tobacco products from one’s environment. When counseling a patient, clinicians should focus on three things: 1) Assisting the patient in identifying potential triggers or situations where the patient may be tempted to relapse, such as certain activities, locations, social events, or emotional states; 2) Assisting the patient in developing coping skills (behavioral and cognitive) to avoid such situations; and 3) Providing helpful information about quitting, such as cessation services (e.g., telephone quit lines, local tobacco cessation programs) and medications.

Clinicians should recommend and discuss approved medications for tobacco cessation with all patients making a quit attempt, except in the uncommon event of medical contraindications. Tobacco cessation medications work in two ways: 1) Helping to reduce physical symptoms of withdrawal, allowing the patient to focus on the behavioral changes needed to be successful in their quit attempt; and 2) Desensitizing nicotine receptors, resulting in the elimination or reduction of the reinforcing (or “rewarding”) effects of nicotine on the body.164 Precautions, patient preferences, and contraindications of all medications should be considered before recommending and prescribing. Most health authorities do not support the use of e-cigarettes as a cessation aid, although emerging evidence suggests effectiveness when used with counseling support. The trials have been carried out under tightly controlled circumstances: more studies applicable to realistic patient contexts are required.

It is important to Arrange for follow-up with patients throughout the process of a quit attempt. For patients willing to make a quit attempt, the first in-person or telephone follow-up visit should be scheduled within the first week of the quit attempt, with the second recommended within a month of the quit date. It is important to congratulate those who have remained abstinent and support those that have relapsed, for instance, by providing additional counseling and/or referral to more intensive treatment. For patients unwilling to make a quit attempt, clinicians should reassess their stage of change at their next dental appointment.

For clinicians who do not have the time or resources to implement the 5 A’s approach, and where there is an appropriate specialist stop smoking service available, an alternative approach known as Ask-Advise-Act (AAA) is a viable strategy (Figure 1). This truncated version of the 5 A’s approach involves Asking about (and recording) tobacco use, Advising patients on the personal benefits of quitting and that evidence shows the best way is with a combination of support and treatment, and Acting on the patients response, either prescribing, monitoring, or referring. Interestingly, the “advise” step deliberately leaves out the harms of tobacco use in order to minimize the duration of the intervention and avoid a defensive reaction from patients likely already well-aware that tobacco use is dangerous. This and similar three-step approaches to tobacco cessation are recommended worldwide.160,163,165–168 The 5 A’s and Ask-Advise-Act model have been shown to be similarly effective in improving cessation rates among patients when compared to no intervention.158,167,169

Treatment Considerations for Periodontal Patients

As discussed previously, tobacco use has significant negative effects on oral health and the outcome of almost all therapeutic periodontal procedures. Additionally, cigarette smokers have been shown to be less likely than non-smokers to follow through with supportive periodontal/peri-implant therapy or periodontal maintenance, further increasing their risk of poor outcomes.170 Periodontal patients with planned treatment are ideal candidates for tobacco cessation intervention, as they are often receiving treatment for conditions directly related to their tobacco use. Ideally, patients should quit tobacco use successfully prior to any type of periodontal treatment to improve outcomes, such as fewer implant failures and improved wound healing post-surgery. However, despite tobacco use being one of the most significant risk factors for poor periodontal outcomes, it is not considered a complete treatment contraindication.74,171 In the event that a patient is unwilling or unable to quit, providers must weigh the risks and benefits of treatment and discuss potential outcomes with the patient prior to making decisions on whether to move forward with treatment.

Recommendations for managing periodontal disease in tobacco-using patients differ considerably across the literature, with varying levels of supporting evidence. For patients receiving dental implants, one study suggested that patients should abstain from tobacco use one week prior to surgery and two months post-surgery to allow for proper wound healing.172 Other authors have opined that providers should encourage patients to abstain from use indefinitely in order to reduce complications and improve success rates post-surgery.173 The Royal College of Surgeons of England recommends that National Health Service-funded implants should not be placed until three months after quitting.174 Guidelines from the American College of Prosthodontics, without explicitly citing tobacco use, recommend that patients at higher risk for negative clinical outcomes receive a professional examination more often than every 6 months.175 Based on limited evidence and lacking in consistency, current guidelines and recommendations for managing periodontal conditions in the tobacco-using patient leave dental professionals to apply sound judgment in managing risk for unfavorable treatment outcomes. Additional clinical data are needed to evaluate preventive and therapeutic interventions for tobacco-using patients. For now, patients must be informed of the risks associated with continued tobacco use and encouraged to make a quit attempt with evidence-based help from their dental provider through direct support or referral to cessation services.

Acknowledgements:

Benjamin Chaffee and Elizabeth Couch received funding from the United States National Institutes of Health (Grant: U54HL147127) and the California Department of Public Health (Contract: 17-10592). Richard Holliday is funded by a United Kingdom National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Lectureship. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the United States National Institutes of Health, California Department of Public Health, National Health Service (United Kingdom), the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care (United Kingdom). The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this publication.

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396: 1223–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slater SJ, Chaloupka FJ, Wakefield M, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. The impact of retail cigarette marketing practices on youth smoking uptake. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007; 161: 440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019; 68: 1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierce JP. International comparisons of trends in cigarette smoking prevalence. Am J Public Health 1989; 79: 152–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.HMSO Office for National Statistics. Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2019. London: 2020. Available at: https://wwwonsgovuk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/bulletins/adultsmokinghabitsingreatbritain/2019 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pesce G, Marcon A, Calciano L, et al. Time and age trends in smoking cessation in Europe. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0211976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang M, Luo X, Xu S, et al. Trends in smoking prevalence and implication for chronic diseases in China: serial national cross-sectional surveys from 2003 to 2013. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7: 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baleta A Africa’s struggle to be smoke free. Lancet 2010; 375: 107–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kostova D, Tesche J, Perucic AM, Yurekli A, Asma S. Exploring the relationship between cigarette prices and smoking among adults: a cross-country study of low- and middle-income nations. Nicotine Tob Res 2014; 16Suppl 1: S10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen-Grozavu FT, Pierce JP, Sakuma KK, et al. Widening disparities in cigarette smoking by race/ethnicity across education level in the United States. Prev Med 2020; 139: 106220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prochaska JJ, Das S, Young-Wolff KC. Smoking, mental illness, and public health. Annu Rev Public Health 2017; 38: 165–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stepanov I, Woodward A. Heated tobacco products: things we do and do not know. Tob Control 2018; 27: s7–s8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robichaud MO, Seidenberg AB, Byron MJ. Tobacco companies introduce ‘tobacco-free’ nicotine pouches. Tob Control 2019. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agrawal A, Budney AJ, Lynskey MT. The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: a review. Addiction 2012; 107: 1221–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemyre A, Poliakova N, Bélanger RE. The relationship between tobacco and cannabis use: a review. Subst Use Misuse 2019; 54: 130–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franz CA, Frishman WH. Marijuana use and cardiovascular disease. Cardiol Rev 2016; 24: 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winhusen T, Theobald J, Kaelber DC, Lewis D. Regular cannabis use, with and without tobacco co-use, is associated with respiratory disease. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019; 204: 107557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tashkin DP. Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013; 10: 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warnakulasuriya S, Dietrich T, Bornstein MM, et al. Oral health risks of tobacco use and effects of cessation. Int Dent J 2010; 60: 7–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winn DM. Tobacco use and oral disease. J Dent Educ 2001; 65: 306–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. WHO monograph on tobacco cessation and oral health integration. Geneva: 2017. 9241512679. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyle P, Macfarlane GJ, Maisonneuve P, Zheng T, Scully C, Tedesco B. Epidemiology of mouth cancer in 1989: a review. J R Soc Med 1990; 83: 724–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gandini S, Botteri E, Iodice S, et al. Tobacco smoking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2008; 122: 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anantharaman D, Marron M, Lagiou P, et al. Population attributable risk of tobacco and alcohol for upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Oral Oncol 2011; 47: 725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreno-López LA, Esparza-Gómez GC, González-Navarro A, Cerero-Lapiedra R, González-Hernández MJ, Domínguez-Rojas V. Risk of oral cancer associated with tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and oral hygiene: a case-control study in Madrid, Spain. Oral Oncol 2000; 36: 170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothman K, Keller A. The effect of joint exposure to alcohol and tobacco on risk of cancer of the mouth and pharynx. J Chronic Dis 1972; 25: 711–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S, Jee SH, Shin HR, et al. Attributable fraction of tobacco smoking on cancer using population-based nationwide cancer incidence and mortality data in Korea. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negri E, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, Tavani A. Attributable risk for oral cancer in Northern Italy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1993; 2: 189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westra WH. The changing face of head and neck cancer in the 21st Century: the impact of HPV on the epidemiology and pathology of oral cancer. Head Neck Pathol 2009; 3: 78–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanner T, Kämppi A, Päkkilä J, et al. Association of smoking and snuffing with dental caries occurrence in a young male population in Finland: a cross-sectional study. Acta Odontol Scand 2014; 72: 1017–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riley JL 3rd, Tomar SL, Gilbert GH. Smoking and smokeless tobacco: increased risk for oral pain. J Pain 2004; 5: 218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benedetti G, Campus G, Strohmenger L, Lingström P. Tobacco and dental caries: a systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand 2013; 71: 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergeron EJ. De la Stomatite ulcéreuse des soldats et de son identité avec la stomatite des enfants, dite couenneuse, diphthéritique, ulcéro-membraneuse. Labé 1859; 70. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pindborg JJ. Tobacco and gingivitis; correlation between consumption of tobacco, ulceromembranous gingiivitis and calculus. J Dent Res 1949; 28: 460–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ludwick W, Massler M. Relation of dental caries experience and gingivitis to cigarette smoking in males 17 to 21 years old (at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center). J Dent Res 1952; 31: 319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arno A, Waerhaug J, Lovdal A, Schei O. Incidence of gingivitis as related to sex, occupation, tobacco consumption, toothbrushing, and age. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1958; 11: 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brandtzaeg P, Jamison HC. A study of periodontal health and oral hygiene in Norwegian army recruits. J Periodontol 1964; 35: 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheiham A Periodontal disease and oral cleanliness in tobacco smokers. J Periodontol 1971; 42: 259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Summers CJ, Oberman A. Association of oral disease with 12 selected variables. II. edentulism. J Dent Res 1968; 47: 594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preber H, Kant T. Effect of tobacco-smoking on periodontal tissue of 15-year-old schoolchildren. J Periodontal Res 1973; 8: 278–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Preber H, Kant T, Bergström J. Cigarette smoking, oral hygiene and periodontal health in Swedish army conscripts. J Clin Periodontol 1980; 7: 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: findings from NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol 2000; 71: 743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eke PI, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, et al. Risk indicators for periodontitis in US adults: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol 2016; 87: 1174–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Do LG, Slade GD, Roberts-Thomson KF, Sanders AE. Smoking-attributable periodontal disease in the Australian adult population. J Clin Periodontol 2008; 35: 398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinez-Canut P, Lorca A, Magán R. Smoking and periodontal disease severity. J Clin Periodontol 1995; 22: 743–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun HY, Jiang H, Du MQ, et al. The Prevalence and associated factors of periodontal disease among 35 to 44-year-old Chinese adults in the 4th National Oral Health Survey. Chin J Dent Res 2018; 21: 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corraini P, Baelum V, Pannuti CM, Pustiglioni AN, Romito GA, Pustiglioni FE. Periodontal attachment loss in an untreated isolated population of Brazil. J Periodontol 2008; 79: 610–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergström J, Eliasson S. Noxious effect of cigarette smoking on periodontal health. J Periodontal Res 1987; 22: 513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torrungruang K, Tamsailom S, Rojanasomsith K, et al. Risk indicators of periodontal disease in older Thai adults. J Periodontol 2005; 76: 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Susin C, Oppermann RV, Haugejorden O, Albandar JM. Periodontal attachment loss attributable to cigarette smoking in an urban Brazilian population. J Clin Periodontol 2004; 31: 951–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergström J, Eliasson S, Dock J. A 10-year prospective study of tobacco smoking and periodontal health. J Periodontol 2000; 71: 1338–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bolin A, Eklund G, Frithiof L, Lavstedt S. The effect of changed smoking habits on marginal alveolar bone loss. A longitudinal study. Swed Dent J 1993; 17: 211–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haas AN, Wagner MC, Oppermann RV, Rösing CK, Albandar JM, Susin C. Risk factors for the progression of periodontal attachment loss: a 5-year population-based study in South Brazil. J Clin Periodontol 2014; 41: 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomson WM, Broadbent JM, Welch D, Beck JD, Poulton R. Cigarette smoking and periodontal disease among 32-year-olds: a prospective study of a representative birth cohort. J Clin Periodontol 2007; 34: 828–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Helal O, Göstemeyer G, Krois J, Fawzy El Sayed K, Graetz C, Schwendicke F. Predictors for tooth loss in periodontitis patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 2019; 46: 699–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dietrich T, Walter C, Oluwagbemigun K, et al. Smoking, Smoking cessation, and risk of tooth loss: The EPIC-Potsdam Study. J Dent Res 2015; 94: 1369–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dietrich T, Maserejian NN, Joshipura KJ, Krall EA, Garcia RI. Tobacco use and incidence of tooth loss among US male health professionals. J Dent Res 2007; 86: 373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barbour SE, Nakashima K, Zhang JB, et al. Tobacco and smoking: environmental factors that modify the host response (immune system) and have an impact on periodontal health. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 1997; 8: 437–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palmer RM, Wilson RF, Hasan AS, Scott DA. Mechanisms of action of environmental factors--tobacco smoking. J Clin Periodontol 2005; 32Suppl 6: 180–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar PS, Matthews CR, Joshi V, de Jager M, Aspiras M. Tobacco smoking affects bacterial acquisition and colonization in oral biofilms. Infect Immun 2011; 79: 4730–4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shchipkova AY, Nagaraja HN, Kumar PS. Subgingival microbial profiles of smokers with periodontitis. J Dent Res 2010; 89: 1247–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buduneli N, Scott DA. Tobacco-induced suppression of the vascular response to dental plaque. Mol Oral Microbiol 2018; 33: 271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kallala R, Barrow J, Graham SM, Kanakaris N, Giannoudis PV. The in vitro and in vivo effects of nicotine on bone, bone cells and fracture repair. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2013; 12: 209–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sørensen LT. Wound healing and infection in surgery: the pathophysiological impact of smoking, smoking cessation, and nicotine replacement therapy: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2012; 255: 1069–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holliday RS, Campbell J, Preshaw PM. Effect of nicotine on human gingival, periodontal ligament and oral epithelial cells. A systematic review of the literature. J Dent 2019; 86: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaffee BW, Couch ET, Ryder MI. The tobacco-using periodontal patient: role of the dental practitioner in tobacco cessation and periodontal disease management. Periodontol 2000 2016; 71: 52–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Labriola A, Needleman I, Moles DR. Systematic review of the effect of smoking on nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000 2005; 37: 124–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.D’Aiuto F, Ready D, Parkar M, Tonetti MS. Relative contribution of patient-, tooth-, and site-associated variability on the clinical outcomes of subgingival debridement. I. Probing depths. J Periodontol 2005; 76: 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grossi SG, Zambon J, Machtei EE, et al. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on healing after mechanical periodontal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc 1997; 128: 599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Preshaw PM, Holliday R, Law H, Heasman PA. Outcomes of non-surgical periodontal treatment by dental hygienists in training: impact of site- and patient-level factors. Int J Dent Hyg 2013; 11: 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ah MK, Johnson GK, Kaldahl WB, Patil KD, Kalkwarf KL. The effect of smoking on the response to periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol 1994; 21: 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kotsakis GA, Javed F, Hinrichs JE, Karoussis IK, Romanos GE. Impact of cigarette smoking on clinical outcomes of periodontal flap surgical procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol 2015; 86: 254–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lindfors LT, Tervonen EA, Sándor GK, Ylikontiola LP. Guided bone regeneration using a titanium-reinforced ePTFE membrane and particulate autogenous bone: the effect of smoking and membrane exposure. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010; 109: 825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Patel RA, Wilson RF, Palmer RM. The effect of smoking on periodontal bone regeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol 2012; 83: 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andia DC, Martins AG, Casati MZ, Sallum EA, Nociti FH. Root coverage outcome may be affected by heavy smoking: a 2-year follow-up study. J Periodontol 2008; 79: 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hasanoglu Erbasar GN, Hocaoğlu TP, Erbasar RC. Risk factors associated with short dental implant success: a long-term retrospective evaluation of patients followed up for up to 9 years. Braz Oral Res 2019; 33: e030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen H, Liu N, Xu X, Qu X, Lu E. Smoking, radiotherapy, diabetes and osteoporosis as risk factors for dental implant failure: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013; 8: e71955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.National Cancer Institute, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smokeless tobacco and public health: a global perspective. In: NIH Publication No. 14–7983, Bethesda, MD: US; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khan Z, Tönnies J, Müller S. Smokeless tobacco and oral cancer in South Asia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Cancer Epidemiol 2014; 2014: 394696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans International Agency for Research on Cancer World Health Organization. Smokeless tobacco and some tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Vol 89: World Health Organization; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 83.US Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Smokeless Tobacco Report for 2018. Washington, DC: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chang JT, Levy DT, Meza R. Trends and factors related to smokeless tobacco use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 2016; 18: 1740–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.US Food and Drug Administration. Tobacco product standard for n-nitrosonornicotine level in finished smokeless tobacco products. In. Fed Register. Vol 822017:8004–8053. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ernster VL, Grady DG, Greene JC, et al. Smokeless tobacco use and health effects among baseball players. JAMA 1990; 264: 218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Robertson PB, Walsh M, Greene J, Ernster V, Grady D, Hauck W. Periodontal effects associated with the use of smokeless tobacco. J Periodontol 1990; 61: 438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Greer RO Jr., Poulson TC. Oral tissue alterations associated with the use of smokeless tobacco by teen-agers. Part I. Clinical findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1983; 56: 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Offenbacher S, Weathers DR. Effects of smokeless tobacco on the periodontal, mucosal and caries status of adolescent males. J Oral Pathol 1985; 14: 169–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fisher MA, Taylor GW, Tilashalski KR. Smokeless tobacco and severe active periodontal disease, NHANES III. J Dent Res 2005; 84: 705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ebbert JO, Elrashidi MY, Stead LF. Interventions for smokeless tobacco use cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 2015: Cd004306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pickworth WB, Rosenberry ZR, Yi D, Pitts EN, Lord-Adem W, Koszowski B. Cigarillo and little cigar mainstream smoke constituents from replicated human smoking. Chem Res Toxicol 2018; 31: 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco product use among adults - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67: 1225–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco-product use by adults and youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Albandar JM, Streckfus CF, Adesanya MR, Winn DM. Cigar, pipe, and cigarette smoking as risk factors for periodontal disease and tooth loss. J Periodontol 2000; 71: 1874–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Krall EA, Garvey AJ, Garcia RI. Alveolar bone loss and tooth loss in male cigar and pipe smokers. J Am Dent Assoc 1999; 130: 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Feldman RS, Bravacos JS, Rose CL. Association between smoking different tobacco products and periodontal disease indexes. J Periodontol 1983; 54: 481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ismail AI, Burt BA, Eklund SA. Epidemiologic patterns of smoking and periodontal disease in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc 1983; 106: 617–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vora MV, Chaffee BW. Tobacco-use patterns and self-reported oral health outcomes: A cross-sectional assessment of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study, 2013–2014. J Am Dent Assoc 2019; 150: 332–344.e332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Majeed BA, Sterling KL, Weaver SR, Pechacek TF, Eriksen MP. Prevalence and harm perceptions of hookah smoking among U.S. adults, 2014–2015. Addict Behav 2017; 69: 78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hair E, Rath JM, Pitzer L, et al. Trajectories of hookah use: harm perceptions from youth to young adulthood. Am J Health Behav 2017; 41: 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jawad M, Choaie E, Brose L, et al. Waterpipe tobacco use in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional study among university students and stop smoking practitioners. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0146799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Perraud V, Lawler MJ, Malecha KT, et al. Chemical characterization of nanoparticles and volatiles present in mainstream hookah smoke. Aerosol Sci Technol 2019; 53: 1023–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Daher N, Saleh R, Jaroudi E, et al. Comparison of carcinogen, carbon monoxide, and ultrafine particle emissions from narghile waterpipe and cigarette smoking: Sidestream smoke measurements and assessment of second-hand smoke emission factors. Atmos Environ (1994) 2010; 44: 8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Waziry R, Jawad M, Ballout RA, Al Akel M, Akl EA. The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2017; 46: 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bibars AR, Obeidat SR, Khader Y, Mahasneh AM, Khabour OF. The effect of waterpipe smoking on periodontal health. Oral Health Prev Dent 2015; 13: 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Javed F, Al-Kheraif AA, Rahman I, et al. Comparison of clinical and radiographic periodontal status between habitual water-pipe smokers and cigarette smokers. J Periodontol 2016; 87: 142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Natto S, Baljoon M, Bergström J. Tobacco smoking and periodontal bone height in a Saudi Arabian population. J Clin Periodontol 2005; 32: 1000–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Baljoon M, Natto S, Abanmy A, Bergström J. Smoking and vertical bone defects in a Saudi Arabian population. Oral Health Prev Dent 2005; 3: 173–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Javed F, Rahman I, Romanos GE. Tobacco-product usage as a risk factor for dental implants. Periodontol 2000 2019; 81: 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime World Drug Report 2017. United Nations Publications; New York, NY: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2019 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Releases. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2019-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases. [PubMed]

- 113.Han BH, Palamar JJ. Trends in cannabis use among older adults in the United States, 2015–2018. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180: 609–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cho CM, Hirsch R, Johnstone S. General and oral health implications of cannabis use. Aust Dent J 2005; 50: 70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Thomson WM, Poulton R, Broadbent JM, et al. Cannabis smoking and periodontal disease among young adults. JAMA 2008; 299: 525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Meier MH, Caspi A, Cerdá M, et al. Associations between cannabis use and physical health problems in early midlife: a longitudinal comparison of persistent cannabis vs tobacco users. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73: 731–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jamieson LM, Gunthorpe W, Cairney SJ, Sayers SM, Roberts-Thomson KF, Slade GD. Substance use and periodontal disease among Australian Aboriginal young adults. Addiction 2010; 105: 719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.López R, Baelum V. Cannabis use and destructive periodontal diseases among adolescents. J Clin Periodontol 2009; 36: 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ortiz AP, González D, Ramos J, Muñoz C, Reyes JC, Pérez CM. Association of marijuana use with oral HPV infection and periodontitis among Hispanic adults: Implications for oral cancer prevention. J Periodontol 2018; 89: 540–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shariff JA, Ahluwalia KP, Papapanou PN. Relationship between frequent recreational cannabis (marijuana and hashish) use and periodontitis in adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011 to 2012. J Periodontol 2017; 88: 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Versteeg PA, Slot DE, van der Velden U, van der Weijden GA. Effect of cannabis usage on the oral environment: a review. Int J Dent Hyg 2008; 6: 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Russell C, Rueda S, Room R, Tyndall M, Fischer B. Routes of administration for cannabis use - basic prevalence and related health outcomes: A scoping review and synthesis. Int J Drug Policy 2018; 52: 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Darling MR, Arendorf TM. Review of the effects of cannabis smoking on oral health. Int Dent J 1992; 42: 19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 5: Cd000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gilbert HA, Inventor; U.S. Patent 3,200,819, issued August 17, 1965. Smokeless non-tobacco cigarette. 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Dinakar C, O’Connor GT. The Health Effects of Electronic Cigarettes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1372–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.US Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products. Final rule. Federal Register 2016. Document Number 2016–10685 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 629–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Eisenberg MJ, Hébert-Losier A, Windle SB, et al. Effect of e-Cigarettes plus counseling vs counseling alone on smoking cessation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324: 1844–1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Beard E, West R, Michie S, Brown J. Association of prevalence of electronic cigarette use with smoking cessation and cigarette consumption in England: a time-series analysis between 2006 and 2017. Addiction 2020; 115: 961–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pierce JP, Benmarhnia T, Chen R, et al. Role of e-cigarettes and pharmacotherapy during attempts to quit cigarette smoking: The PATH Study 2013–16. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0237938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Chen R, Pierce JP, Leas EC, et al. E-Cigarette use to aid long-term smoking cessation in the US: prospective evidence from the PATH cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2020. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Borrelli B, O’Connor GT. E-cigarettes to assist with smoking cessation. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 678–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2014; 23: 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Goniewicz ML, Gawron M, Smith DM, Peng M, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL. Exposure to nicotine and selected toxicants in cigarette smokers who switched to electronic cigarettes: a longitudinal within-subjects observational study. Nicotine Tob Res 2017; 19: 160–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wang TW, Neff LJ, Park-Lee E, Ren C, Cullen KA, King BA. E-cigarette use among middle and high school students - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69: 1310–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Xie W, Kathuria H, Galiatsatos P, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with incident respiratory conditions among US adults From 2013 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e2020816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rao P, Liu J, Springer ML. JUUL and combusted cigarettes comparably impair endothelial function. Tob Regul Sci 2020; 6: 30–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Gotts JE, Jordt SE, McConnell R, Tarran R. What are the respiratory effects of e-cigarettes? BMJ 2019; 366: l5275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yang I, Sandeep S, Rodriguez J. The oral health impact of electronic cigarette use: a systematic review. Crit Rev Toxicol 2020; 50: 97–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ganesan SM, Dabdoub SM, Nagaraja HN, et al. Adverse effects of electronic cigarettes on the disease-naive oral microbiome. Sci Adv 2020; 6: eaaz0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Pushalkar S, Paul B, Li Q, et al. Electronic cigarette aerosol modulates the oral microbiome and increases risk of infection. iScience 2020; 23: 100884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Atuegwu NC, Perez MF, Oncken C, Thacker S, Mead EL, Mortensen EM. Association between regular electronic nicotine product use and self-reported periodontal disease status: Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16. 1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Murthy VH. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a major public health concern. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171: 209–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Mallock N, Pieper E, Hutzler C, Henkler-Stephani F, Luch A. Heated tobacco products: a review of current knowledge and initial assessments. Front Public Health 2019; 7: 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.ClinicalTrials.gov. Effect of Switching from cigarette smoking to the use of IQOS on periodontitis treatment outcome. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03364751. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Hwang JH, Ryu DH, Park SW. Heated tobacco products: Cigarette complements, not substitutes. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019; 204: 107576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.World Health Organization. Toolkit for oral health professionals to deliver brief tobacco interventions in primary care. Geneva: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Carr AB, Ebbert J. Interventions for tobacco cessation in the dental setting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 2012: Cd005084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.American Dental Hygienists Association. ADHA Policy Manual. Chicago, IL: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Canadian Dental Hygienists Association. Tobacco use cessation services and the role of the dental hygienist—A CDHA position paper. Can J Dent Hyg 2004; 38: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Public Health England, Department of Health. Delivering better oral health: An evidence‐based toolkit for prevention. Third Edition. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Tong EK, Strouse R, Hall J, Kovac M, Schroeder SA. National survey of U.S. health professionals’ smoking prevalence, cessation practices, and beliefs. Nicotine Tob Res 2010; 12: 724–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Jannat-Khah DP, McNeely J, Pereyra MR, et al. Dentists’ self-perceived role in offering tobacco cessation services: results from a nationally representative survey, United States, 2010–2011. Prev Chronic Dis 2014; 11: E196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ahmed Z, Preshaw PM, Bauld L, Holliday R. Dental professionals’ opinions and knowledge of smoking cessation and electronic cigarettes: a cross-sectional survey in the north of England. Br Dent J 2018; 225: 947–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Chaffee BW, Urata J, Couch ET, Silverstein S. Dental professionals’ engagement in tobacco, electronic cigarette, and cannabis patient counseling. JDR Clin Trans Res 2020; 5: 133–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Drouin O, McMillen RC, Klein JD, Winickoff JP. E-cigarette advice to patients from physicians and dentists in the United States. Am J Health Promot 2018; 32: 1228–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med 2008; 35: 158–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Canadian Action Network for the Advancement, Dissemination and Adoption of Practice-informed Tobacco Treatment, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Canadian Smoking Cessation Clinical Practice Guideline. Toronto, Canada: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 160.The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Supporting smoking cessation: A guide for health professionals. 2nd ed.East Melbourne, Vic: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 161.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol 1992; 47: 1102–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford press; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 163.McGuire H, Desai M, Leng G, Richardson J. NICE public health guidance update. J Public Health (Oxf) 2018; 40: 900–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Prochaska JJ, Benowitz NL. The past, present, and future of nicotine addiction therapy. Annu Rev Med 2016; 67: 467–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Cancer Care Ontario. Smoking cessation information for healthcare providers. Toronto, ON: 2017. [Google Scholar]