Abstract

Background:

Although the literature suggests that attitudes toward evidence-based practices (EBPs) are associated with provider use of EBPs, less is known about the association between attitudes and how competently EBPs are delivered. This study examined how initial attitudes and competence relate to improvements in attitudes and competence following EBP training.

Methods:

Community clinicians (N = 891) received intensive training in cognitive behavioral therapy skills followed by 6 months of consultation. Clinician attitudes were assessed using the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale, and competence was assessed using the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale. Data were analyzed by fitting three latent change score models to examine the relationship between changes in attitudes and competence across the training and within its two phases (workshop phase, consultation phase).

Results:

Latent change models identified significant improvement in attitudes (Mslatent change ⩾ 1.07, SEs ⩽ 0.19, zs ⩾ 6.85, ps < .001) and competence (Mslatent change ⩾ 13.13, SEs ⩽ 3.53, zs ⩾ 2.30, ps < .001) across the full training and in each phase. Higher pre-workshop attitudes predicted significantly greater change in competence in the workshop phase and across the full training (bs ⩾ 1.58, SEs ⩽ 1.13, z ⩾ 1.89, p < .048, β ⩾ .09); however, contrary to our hypothesis, post-workshop attitudes did not significantly predict change in competence in the consultation phase (b = 1.40, SE = 1.07, z = 1.31, p = .19, β = .08). Change in attitudes and change in competence in the training period, the workshop phase, and the consultation phase were not significantly correlated.

Conclusions:

Results indicate that pre-training attitudes about EBPs present a target for implementation interventions, given their relation to changes in both attitudes and competence throughout training. Following participation in initial training workshops, other factors such as subjective norms, implementation culture, or system-level policy shifts may be more predictive of change in competence throughout consultation.

Plain Language Summary

Although previous research has suggested that a learner’s knowledge of evidence-based practices (EBPs) and their attitudes toward EBPs may be related, little is known about the association between a learner’s attitudes and their competence in delivering EBPs. This study examined how initial attitudes and competence relate to improvements in attitudes and competence following training in an EBP. This study suggests that community clinicians’ initial attitudes about evidence-based mental health practices are related to how well they ultimately learn to deliver those practices. This finding suggests that future implementation efforts may benefit from directly targeting clinician attitudes prior to training, rather than relying on more broad-based training strategies.

Keywords: Evidence-based practices, community mental health, implementation, competence, attitudes, cognitive behavioral therapy

Despite decades of research developing effective evidence-based practices (EBPs) such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; for example, Beck, 1964; Fordham et al., 2021), EBPs continue to be underutilized in community mental health clinics (Shafran et al., 2009). Implementation strategies aimed at increasing the adoption and sustainability of CBT in routine practice have achieved limited success (Beidas et al., 2015; McHugh & Barlow, 2010; Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2012). One factor limiting the use of CBT in community care is that despite numerous training initiatives that have aimed to increase clinicians’ skill with CBT, not all participating clinicians ultimately demonstrate increases in skill from these efforts (e.g., Creed et al., 2016; Herschell et al., 2015; Karlin & Cross, 2014). Little is known about the factors that may influence the development of clinicians’ skill in delivering EBPs, which may in turn hinder the identification of strategies to improve implementation and training outcomes. However, a growing body of literature suggests that clinician attitudes about EBPs may change as a result of training, and these attitudes represent key aspects in the transfer of learning process (McLeod et al., 2018).

Fidelity, or the extent to which an intervention has been delivered as intended by the treatment developer and in line with the treatment model, is a key implementation outcome with several related facets (Proctor et al., 2011). Adherence refers to the extent to which the core components of an EBP have been delivered according to the protocol (related to the concept of quantity, or whether the treatment components are present); competence, however, refers to the skillfulness and responsiveness which the clinician delivered the EBP’s components (related to the concept of quality, or how well the treatment components were delivered; McLeod et al., 2021). Efforts have been made to improve competence through training and consultation, but most studies combine multiple strategies, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the contributions of various strategies (Frank et al., 2020; McLeod et al., 2018; Rakovshik & McManus, 2010). However, findings suggest that clinicians’ attitudes, or their ways of thinking about and perceiving EBPs, can change as a result of training and therefore may represent a key factor in building EBP skills (Aarons, 2004; McLeod et al., 2018). Attitudes may influence a clinician’s behavioral intention to deliver an EBP or its components, therefore influencing the clinician’s actions in session (Burgess et al., 2017), including components of CBT (Wolk et al., 2019). Given that attitudes toward EBPs may influence uptake (Addis & Krasnow, 2000; Beidas et al., 2015), clinician training and consultation may explicitly address trainee attitudes toward EBPs. In fact, continued practice of CBT throughout consultation following training has been associated with more improvement in CBT competence (Creed et al., 2016). Therefore, more positive attitudes toward EBPs could lead to greater skill acquisition. Even if clinician attitudes are not specifically targeted during training, training and consultation may still lead to positive changes in attitudes (Bearman et al., 2017; Creed et al., 2016), which models like the theory of planned behavior suggest may contribute to increases in their intention to deliver EBPs and actual in-session behavior (Godin et al., 2008; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Wolk et al., 2019). However, research has not examined the impact of initial levels of EBP attitudes and competence on improvements in attitudes and competence following training.

This study examined how initial levels of clinicians’ attitudes and competence are linked to change in attitudes and competence across different phases of training: the workshop phase (pre-workshop to post-workshop), the consultation phase (post-workshop to post-consultation), and the overall full training process (pre-workshop to post-consultation). We examined each phase of the training separately to determine whether the relationship between (a) initial levels of and (b) change in attitudes and competence differed at various points in training. We hypothesized that for all phases of training (workshop, consultation, and full training), (1) more positive initial attitudes would be associated with less improvement in attitudes, (2) more positive initial attitudes would be associated with greater improvement in competence, (3) higher levels of competence at baseline would be associated with less improvement in competence, (4) initial competence would not be associated with change in attitudes, and (5) change in attitudes and change in competence would be significantly correlated.

Method

Setting and procedures

The University of Pennsylvania’s Beck Community Initiative (Penn BCI) has provided training in transdiagnostic CBT for clinicians in the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services (DBHIDS) since 2009 (Creed et al., 2014). Although the implementation and training model of the Penn BCI and its outcomes have been described elsewhere (Creed et al., 2014; 2016), a brief summary is provided here. In response to a policy initiative from DBHIDS emphasizing EBPs in mental health care, a competitive Request for Application process was initiated for community mental health care organizations in the Philadelphia DBHIDS system. Organizations were invited to submit applications, which were reviewed by members of DBHIDS’s leadership and the Director of the BCI. Review criteria included the organization’s track record from past EBP implementation efforts, identification of adequate staff and resources to participate in training, stated commitment to implementing CBT, and the strength of the described plan to sustain CBT. Based on this review, organizations were selected for participation. The phases of the initiative bear similarities to the Learning Collaborative model of quality improvement, with a planning stage, action stage, and outcome stage (Kopelovich et al., 2019; Powell et al., 2016). Specifically, implementation began with engagement activities with stakeholders across the organization including board members, leadership, clinical staff, and line staff. An Implementation Committee was formed within each organization to develop and execute an implementation plan, typically including a key decision maker (e.g., Chief Operating Officer or Clinical Director), a data analyst or Quality Improvement professional, a supervisor, and a clinician. The Committee met at least monthly to develop and execute strategies to ensure ongoing CBT supervision, adjustment of policies and documentation to support CBT, integration of measurement-based care principles to evaluate individual and aggregate program outcomes (e.g., Scott & Lewis, 2014), and strategies to address capacity lost to turnover. The Committee also met regularly with their Penn BCI instructor and the Penn BCI Director for consultation around best practices and problem-solving to support these goals, but all final decisions were made by the organization’s Implementation Committee.

Clinician training included a 22-hr intensive workshop, held 1 day per week over three consecutive weeks, focused on foundational CBT skills including case conceptualization, treatment planning, cognitive and behavioral interventions, and relapse prevention. After completion of the workshop, all clinicians who participated in the workshop also participated in 6 months of weekly, 2-hr consultation groups focused on the application of CBT with clients on their regular caseloads. All training and consultation were delivered by doctoral-level experts in CBT. Over the course of the training, clinicians were required to submit at least 15 recorded therapy sessions (with appropriate assent/consent) to demonstrate ongoing use of CBT with clients. Among those 15 recordings, four were collected and rated by Penn BCI instructors at pre-determined time points (prior to the workshop, post-workshop, midpoint of consultation, end of consultation) to evaluate clinician competence. Clinicians received narrative feedback about session recordings from instructors and peers during consultation, in addition to detailed written feedback and scores on the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTRS; Young & Beck, 1980) on the final two audio submissions at the pre-determined time points. Clinicians who completed all participation requirements (i.e., attendance at all workshops and 85% of consultations, completion of program evaluation measures, submission of 15 session recordings) and reached the benchmark for competence (CTRS total score ⩾ 40; Shaw et al., 1999) received a Penn BCI certification of competence in CBT. After consultation, clinicians continued meeting as an internal peer supervision group to build skills and prevent drift from the model. Once a program’s initial cohort of clinicians transitioned to an internal supervision group, the workshop content was made available to additional program clinicians through an online platform to increase CBT capacity in the program and address turnover. Clinicians who completed the web-based training then joined their program’s internal supervision group for support in applying CBT with their clients. These clinicians were required to meet the same participation expectations as clinicians trained in the initial expert-led cohort, and Penn BCI instructors rated their CBT competence and provided detailed written feedback at the specified time points. Those participants who met all requirements through the web-based training model were also awarded certification of competence in CBT. The web-based training model has evidenced non-inferiority to the in-person training model in regard to clinicians reaching CBT competence, using only 7% of the resources needed for the initial training groups (German et al., 2017).

Program evaluation data were collected for all Penn BCI participants as part of normal operations, and these data are used to inform ongoing improvement of the Penn BCI process. The first author’s Institutional Review Board deemed these processes to be program evaluation and therefore exempt from oversight. As a part of this program evaluation process, competence for all clinicians was rated from audio-recorded therapy sessions at pre-workshop, post-workshop, and post-consultation. Clinicians also completed a measure of attitudes toward EBPs at each of these time points.

For this study, data analysis was conducted using program evaluation data that had been de-identified and stored separately from all identified program evaluation data. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the first author’s Institutional Review Board, and the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the most recent amendment of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013).

Participants

Participants (N = 891) were all practicing clinicians in community mental health clinics in Philadelphia who participated in the Penn BCI between 2007 and January 2020. A total of 26 agencies participated in the project, with an average of 24.75 clinicians per agency (SD = 22.89). As shown in Table 1, participants were primarily middle age (M = 38.57), female (71%), White (34%) or Black (24%), non-Hispanic (57%), and Master’s-level clinicians (73%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

| Variable | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.57 | 12.11 |

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 634 | 71 |

| Male | 196 | 22 |

| Not reported | 61 | 7 |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 6 | 1 |

| Asian | 23 | 3 |

| Black or African American | 212 | 24 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.1 |

| White | 301 | 34 |

| Other | 39 | 4 |

| Chose not to answer | 10 | 1 |

| Not reported | 317 | 36 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 507 | 57 |

| Latinx | 71 | 8 |

| Not reported | 313 | 35 |

| Highest level of Education | ||

| Some college | 2 | 0.2 |

| Associates | 7 | 0.8 |

| Bachelors | 52 | 6 |

| Masters | 649 | 73 |

| Some doctoral work | 23 | 3 |

| MD | 23 | 3 |

| Doctorate | 42 | 5 |

| Not reported | 93 | 10 |

MD: Doctor of Medicine; SD: standard deviation.

Ethnicity does not add up to 100% because participants had the option to select more than one ethnicity.

Measures

Clinician attitudes

EBPAS is a 15-item self-report measure of clinician attitudes about the utility of EBPs (Aarons, 2004). Participants rated each item on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (to a very great extent). Higher mean scores indicated more positive attitudes about EBPs. EBPAS scores have been shown to predict self-reported adoption and use of EBPs (Aarons et al., 2012; Smith & Manfredo, 2011), as well as knowledge and use of EBPs by mental health care providers (Aarons, 2004; Gray et al., 2007). The EBPAS has evidenced internal consistency of 0.76–0.79), with subscale reliabilities ranging from 0.59 to 0.93 (Aarons, 2004; Aarons et al., 2007, 2010). The EBPAS was collected at baseline (prior to workshops), post-workshop, mid-consultation (3 months after post-workshop), and end of consultation (6 months after post-workshop).

Competence

CTRS is an 11-item independent evaluator assessment of clinician competence (Young & Beck, 1980). Trainers rated recordings of the clinician’s therapy session along 11 items on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (poor) to 6 (excellent); total scores range from 0 to 66, with higher scores indicating greater CBT competence. The established benchmark for CBT competence, a total score of 40 or higher, was used to indicate clinician competence (Shaw et al., 1999). Audio recordings of therapy sessions were gathered and rated at baseline, post-workshop, mid-consultation, and end of consultation. CTRS raters were doctoral-level CBT experts, and demonstrated a high interrater reliability for the CTRS total score (ICC = .84; German et al., 2017). Internal consistency (alpha) across all 11 items has been found to be .94 (Goldberg et al., 2020), and construct validity has been supported with CTRS scores increasing over the course of training in CBT (Creed et al., 2016).

Demographic questionnaire

Participants were asked to indicate their age, gender, race, ethnicity, and highest level of education. They were able to select multiple options for race; each race was coded dichotomously as checked or unchecked.

Analytic plan

Analyses were conducted in R using the lavaan package (Version 0.6-5; Rosseel, 2012) using full information maximum likelihood estimation to account for missingness. No participants were excluded from analyses. We followed Kievit and colleagues’ (2018) code to estimate bivariate latent change models. This analytic approach was chosen to examine the correlation between the latent change in scores between two time points. We fit three latent change score models to examine the relationship between changes in attitudes and competence during the full training process (pre-workshop to post-consultation), the workshop phase (pre-workshop to post-workshop), and the consultation phase (post-workshop to post-consultation). These models examined whether changes in one variable (attitudes or competence) are predicted by levels of that variable and/or the other variable at the previous time point. Change scores are residuals of prediction of each construct (attitudes, competence) at t + 1 (pre-workshop or post-workshop) from t (post-workshop or post-consultation) with coefficients fixed at 1. The intercept and variance of attitudes and competence at time t also were constrained to be 0. The models were just identified, so fit statistics could not be examined. Given that the intraclass correlation between clinician agency and the EBPAS and CTRS at all stages of the training was small (ICCs ⩽ 0.08), agency was not included as a control variable.

Results

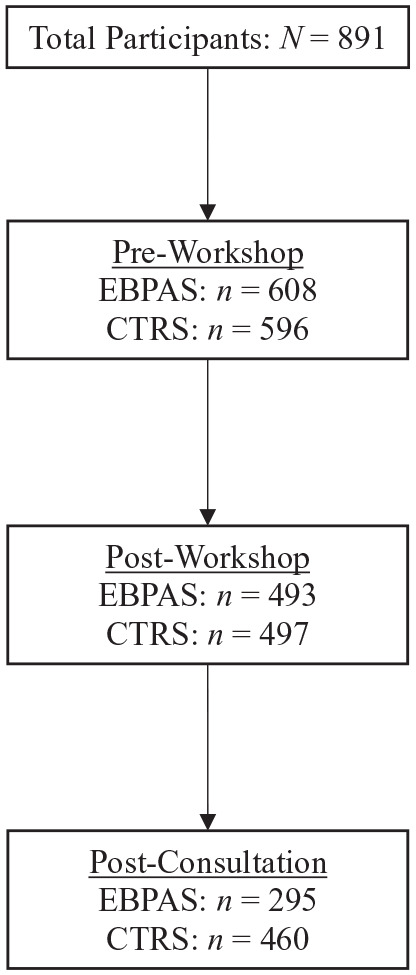

Figure 1 shows the participant flow through the training. Because not all participants completed the EBPAS or CTRS at the 6-month follow-up, attrition analyses were performed. They revealed that participant age, gender, ethnicity, level of education, baseline EBPAS, and baseline CTRS did not significantly affect the probability of a participant completing both the EBPAS and CTRS post-consultation, bs ⩽ 0.01, ps ⩾ .07. However, participants who identified as White and Black were more likely to complete both the EBPAS and CTRS post-consultation than participants who did not identify as being White or Black, bs ⩾ 0.12, ps < .002. Thus, data are considered to be missing not at random. To examine whether differential attrition by race affected the results, we re-ran the models with the post-consultation time point (i.e., the full training model and consultation model) four times, subsetting the data to only include participants who identified as (1) White, (2) non-White, (3) Black, and (4) non-Black. Significant results did not vary based on race. Therefore, we present all results below using the full sample.

Figure 1.

Participant flow throughout the workshop.

Note: EBPAS: Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale; CTRS: Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale; N: number of participants.

Bivariate correlations between all study variables were examined (Table 2). There was a significant correlation between pre-workshop, post-workshop, and post-consultation EBPAS scores; between pre-workshop, post-workshop, and post-consultation CTRS scores; between pre-workshop EBPAS and post-consultation CTRS scores; and between post-workshop EBPAS and post-workshop CTRS scores. All correlations were small, with the exception of the correlations among EBPAS scores, which were in the large range. This suggests that pre-workshop attitudes were strongly related to post-workshop and post-consultation attitudes. Although the mean EBPAS scores appear to be stable throughout training, the significant latent changes in EBPAS scores (see below) during each of the three phases suggest that attitudes about CBT improved overall during the training. The lack of change in mean scores reflects the fact that some participants’ attitudes improved, while others’ attitudes worsened.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-workshop EBPAS | 3.06 | 0.46 | |||||

| 2. Post-workshop EBPAS | 3.03 | 0.48 | .60** | ||||

| 3. Post-consultation EBPAS | 3.03 | 0.45 | .50** | .48** | |||

| 4. Pre-workshop CTRS | 20.47 | 6.57 | .02 | .03 | .05 | ||

| 5. Post-workshop CTRS | 26.87 | 7.47 | .08 | .12* | .12 | .34** | |

| 6. Post-consultation CTRS | 39.79 | 7.79 | .19** | .11 | .05 | .19** | .32** |

CTRS: Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale; EBPAS: Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale; M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

p < .05; **p < .01.

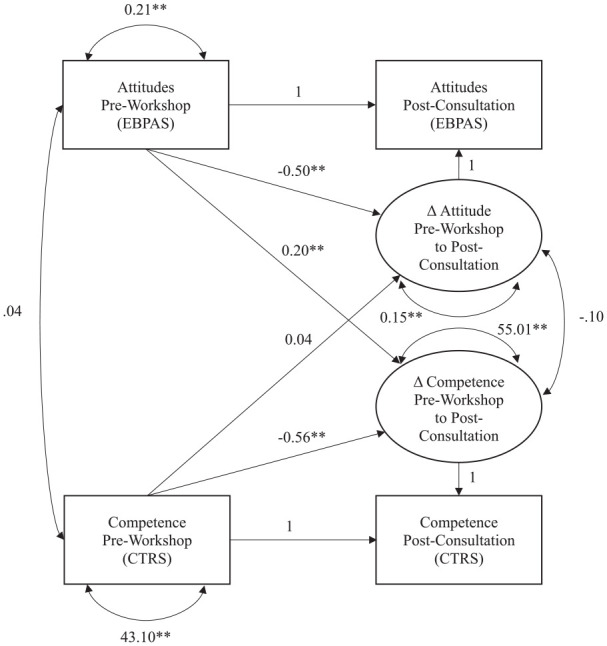

Pre-workshop to post-consultation

Figure 2 depicts the bivariate latent change model examining the relationship between the latent change in attitudes and competence from pre-workshop to post-consultation. There were significant latent changes from pre-workshop to post-consultation on both EBPAS (Mlatent change = 1.41, SE = 0.19, z = 7.47, p < .001) and CTRS (Mlatent change = 22.91, SE = 3.53, z = 6.48, p < .001). There was significant variation in latent change in attitudes (σ2 = 0.15, SE = 0.01, z = 11.81, p < .001) and competence (σ2 = 55.01, SE = 3.91, z = 14.06, p < .001) throughout the full training, indicating that the amount of change in attitudes and competence clinicians experienced from pre-workshop to post-consultation varied significantly between clinicians.

Figure 2.

Bivariate latent change score model: Pre-workshop to post-consultation.

CTRS: Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale; EBPAS: Evidence Based Practice Attitude Scale.

Covariance and regression coefficients are standardized, and variance estimates are unstandardized.

*p < .05; **p < .01; n = 807.

As is shown in Figure 2, the correlation between attitudes and competence at baseline was not significant, indicating that initial attitudes about EBPs were not related to CBT competence (r = .04, p = .15). Baseline attitudes significantly predicted change in attitudes post-consultation (b = –0.49, SE = 0.06, z = –8.98, p < .001, β = –.50), and baseline competence significantly predicted change in competence post-consultation (b = –0.79, SE = 0.06, z = –12.14, p < .001, β = –.56). This indicated that lower levels of baseline attitudes and competence predicted greater change in attitudes and competence respectively throughout the training. Furthermore, baseline attitudes significantly predicted the degree of change in competence after the training, such that more positive pre-workshop attitudes predicted greater change in competence (b = 4.09, SE = 1.13, z = 3.63, p < .001, β = .20). However, baseline competence did not significantly predict the degree of change in attitudes following the training (b = 0.003, SE = 0.004, z = 0.70, p = .49, β = .04). Finally, the estimate of correlated change was not significant, indicating that change in attitudes was not significantly related to change in competence throughout the training (r = –.10, p = .15). Overall, pre-workshop attitudes about EBPs were associated with change in both in attitudes and competence post-consultation, whereas baseline levels of competence predicted change in competence, but not attitudes post-consultation.

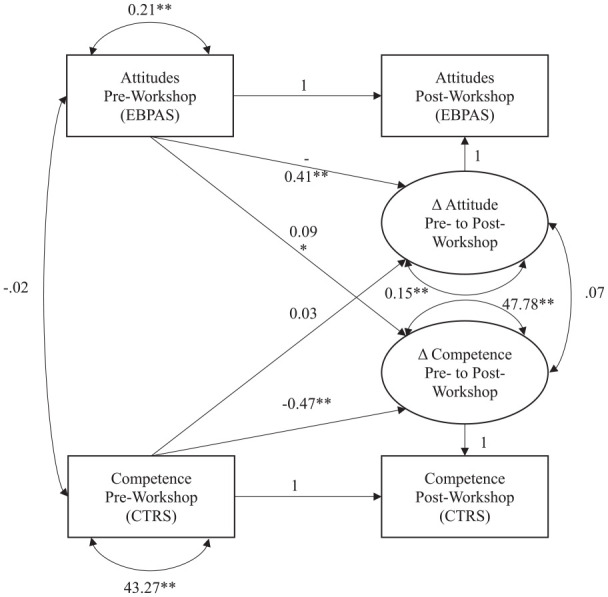

Pre-workshop to post-workshop

Figure 3 depicts the bivariate latent change model examining the relationship between the latent change in attitudes and competence from pre- to post-workshop. There were significant latent changes from pre- to post-workshop on both EBPAS (Mlatent change = 1.07, SE = 0.13, z = 8.13, p < .001) and CTRS (Mlatent change = 13.13, SE = 2.74, z = 4.80, p < .001). There was significant variation in latent change in attitudes (σ2 = 0.15, SE = 0.01, z = 15.16, p < .001) and competence (σ2 = 47.78, SE = 3.20, z = 14.93, p < .001) throughout the workshop phase, indicating that the amount of change in attitudes and competence clinicians experienced during the workshop phase varied significantly between clinicians.

Figure 3.

Bivariate latent change score model: Pre-workshop to post-workshop.

CTRS: Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale; EBPAS: Evidence Based Practice Attitude Scale.

Note: n = 810; Covariance and regression coefficients are standardized, and variance estimates are unstandardized.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

As shown in Figure 3, the correlation between attitudes and competence at baseline also was not significant in this model, indicating that initial attitudes about EBPs were not related to CBT competence (r = –.02, p = .64). In addition, baseline attitudes significantly predicted change in attitudes post-workshop (b = –0.37, SE = 0.04, z = –9.58, p < .001, β = –.41), and baseline competence significantly predicted change in competence post-workshop (b = –0.57, SE = 0.06, z = –9.98, p < .001, β = –.47). This indicated that lower levels of baseline attitudes and competence predicted greater change in attitudes and competence respectively throughout the workshop. Furthermore, baseline attitudes significantly predicted the degree of change in competence following the workshop, such that more positive pre-workshop attitudes predicted greater change in competence (b = 1.58, SE = 0.80, z = 1.98, p = .048, β = .09). However, baseline competence did not significantly predict the degree of change in attitudes following the workshop (b = 0.002, SE = 0.003, z = 0.56, p = .58, β = .03). Finally, the estimate of correlated change was not significant, which indicated that that change in attitudes was not significantly related to change in competence (r = .07, p = .19). As seen in the pre-workshop to post-consultation model, pre-workshop attitudes about EBPs were associated with change in both attitudes and competence post-workshop, whereas baseline levels of competence predicted change in competence, but not attitudes post-workshop.

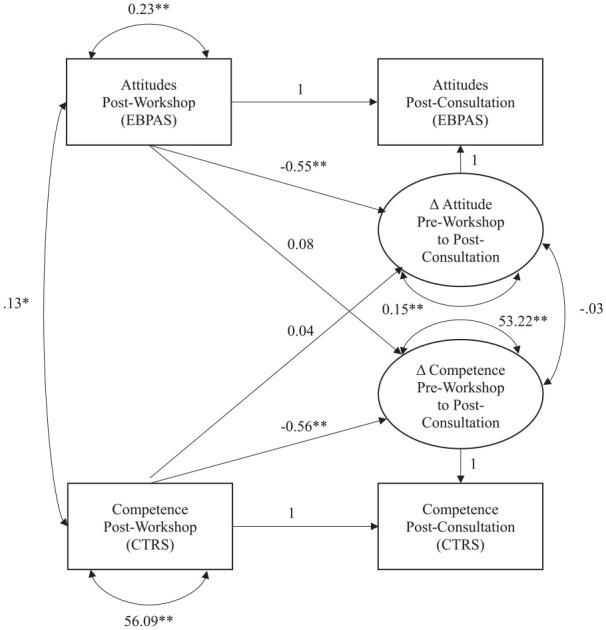

Post-workshop to post-consultation

Figure 4 depicts the bivariate latent change model examining the relationship between the latent change in attitudes and competence from post-workshop to post-consultation. There were significant latent changes from post-workshop to post-consultation on both EBPAS (Mlatent change = 1.54, SE = 0.17, z = 6.85, p < .001) and CTRS (Mlatent change = 26.42, SE = 2.30, z = 8.02, p < .001). Again, there was significant variation in latent change in attitudes (σ2 = 0.15, SE = 0.01, z = 12.02, p < .001), and latent change in competence (σ2 = 53.22, SE = 3.70, z = 14.38, p < .001) throughout the consultation phase, which indicated that the amount of change in attitudes and competence clinicians experienced during the consultation phase varied significantly between clinicians.

Figure 4.

Bivariate latent change score model: Post-workshop to post-consultation.

CTRS: Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale; EBPAS: Evidence Based Practice Attitude Scale.

Note: n = 672. Covariance and regression coefficients are standardized, and variance estimates are unstandardized.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

As is shown in Figure 4, the correlation between attitudes and competence at post-workshop was significant, indicating that post-workshop attitudes about EBPs were related to CBT competence (r = .13, p = .01). In addition, as seen in the other models, post-workshop attitudes significantly predicted change in attitudes post-consultation (b = –0.53, SE = 0.05, z = –10.35, p < .001, β = –.55), and post-workshop competence significantly predicted change in competence post-consultation (b = –0.66, SE = 0.05, z = –12.23, p < .001, β = –.56). This indicated that lower levels of post-workshop attitudes and competence predicted greater change in attitudes and competence respectively throughout the consultation phase. Unlike the other models, post-workshop attitude did not significantly predict the degree of change in competence after the training (b = 1.40, SE = 1.07, z = 1.31, p = .19, β = .08). As seen in the other two models, post-workshop competence did not significantly predict the degree of change in attitudes following the training (b = 0.002, SE = 0.004, z = 0.68, p = .50, β = .04). Finally, the estimate of correlated change was not significant, suggesting that change in attitudes was not significantly related to change in competence throughout the consultation phase (r = –.03, p = .65). Overall, this indicated that although post-workshop attitudes and competency were related to each other, post-workshop attitudes and competency were not predictive of change competency and attitudes (respectively) during the consultation phase.

Discussion

The study findings support that early (pre-workshop or post-workshop) attitudes about EBPs and competence in CBT affect change in both attitudes and competence throughout a full-training program, and within the workshop and consultation phases of that program. There was a significant improvement in both attitudes and competence throughout the entire training program, the workshop phase, and the consultation phase, especially for clinicians with less favorable initial attitudes, as noted below. This finding is in line with previous research which found that EBP attitudes and CBT competence improved after training and consultation in CBT (Creed et al., 2016).

The hypothesis that initial attitudes predict change in competence was partially supported. Higher pre-workshop attitudes predicted significantly greater change in competence during the workshop phase and during the entire training. Clinicians with more favorable attitudes toward EBP at the outset of training experienced the most benefit from training and showed the most improvement in CBT competence both after the workshop phase and after the consultation phase of training. This finding is in line both with previous work that suggests that favorable attitudes toward EBP predict subsequent use of EBPs (Addis & Krasnow, 2000; Beidas et al., 2015), and with the theory of planned behavior such that attitudes influence a clinician’s intention to use the EBP, and by extension, their behavior in session (Godin et al., 2008; Wolk et al., 2019). Alternatively, EBP use may mediate the relationship between attitudes and competence; however, use of CBT in routine clinical practice was not directly measured in this study. Given that attitudes toward EBPs are predictive of improvement in CBT skill following training, it may be beneficial to directly assess attitudes before training to have information about which clinicians may need additional support for reaching competency expectations during training.

Contrary to our hypothesis, post-workshop attitudes did not significantly predict change in competence in the consultation phase. Given that previous literature has found that EBP attitudes predict EBP use (Beidas et al., 2015), and EBP use is associated with higher levels of EBP competence, it was surprising that post-workshop attitudes did not significantly predict change in competence during the consultation phase when clinicians practiced the CBT skills they learned in the training. Apparently, and perhaps not surprisingly, attitudes after the workshop are not as relevant as pre-workshop attitudes in predicting change in competence during post-workshop consultation. Upon completion of the workshops, other factors may have been more predictive of change in competence throughout training. For example, knowledge of CBT may indicate how much information from the workshops was understood and retained by clinicians to prepare them to practice CBT skills during the consultation phase. Alternatively, if therapists observe that CBT led to improvement for their clients, this may have also influenced their reported attitudes. This finding may also be a reflection of potential variability in CBT use during the consultation phase, given that clinicians were enrolled in training based on their organization’s response to policy initiatives (rather than by self-selection); changes in subjective norms such as the expectation that they complete the training requirements may have influenced their intention to use CBT (Burgess et al., 2017; Godin et al., 2008). Longer term follow-up data from their routine practice after training completion may provide further insight into the relation among EBP attitudes, CBT use, and CBT competence over time.

Organizational factors may have also affected clinicians’ behavior in relation to subjective norms of their organization or their perceived behavioral control over using CBT in session, including organizational culture and climate (Glisson et al., 2008; Wolk et al., 2019). Conceptual (Aarons et al., 2011; Damschroder et al., 2009) and empirical literature (Hoagwood et al., 2014; Isett et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006) highlight the importance of organizational factors as predictors of EBP implementation outcomes. For example, organization climate (Glisson & Williams, 2015; Kolko et al., 2012; Schoenwald et al., 2009; Williams & Glisson, 2014), organization leadership (Aarons, 2006; Brimhall et al., 2016; Cook et al., 2014, 2015; Farahnak et al., 2020), structure and staffing (Schoenwald et al., 2009; Swales et al., 2012), and readiness for change (Beidas et al., 2014; Garner et al., 2012; Henggeler et al., 2008) have each been linked to implementation outcomes. The ways in which EBPs are emphasized and supported at the system level (e.g., policies, contracting) and organization or clinic levels (e.g., education/training, coaching, performance evaluations, etc.) and communicated by leaders to employees can influence attitudes and behaviors (Barnett et al., 2017; Farahnak et al., 2020).

As hypothesized and as suggested by the literature, initial competence did not significantly predict change in attitudes throughout the full training period, the workshop phase, or the consultation phase. Also as hypothesized, in all three stages of the training, there was a negative association between initial attitudes and improvement in attitudes, and initial competence and change in competence, indicating that clinicians who began training with lower positive attitudes and lower competence experienced more growth in competence over the course of training.

Finally, contrary to our hypothesis, change in attitudes and change in competence during the full training period, the workshop phase, and the consultation phase were not significantly correlated. This suggests that, while baseline attitudes predict improvement in competence over training, improvement in attitudes over time does not. Therefore, changing clinicians’ attitudes toward EBPs during training may not be as useful a target of training as would be attitudes prior to training. The theory of planned behavior may offer a useful conceptualization of ways in which to approach a shift in attitudes, including specific attention to shifts in subjective norms and perceived behavioral control (Burgess et al., 2017). Changing clinician attitudes prior to training may also require addressing organizational climate and leadership given that leadership skill is associated with provider attitudes toward EBPs (Aarons, 2006; Farahnak et al., 2019). Implementation climate and leadership may impact attitudes by incentivizing and focusing on EBP use, making hiring decisions so there are a critical mass of EBP trained therapists, removing barriers to implementation, or shifting subjective norms. Implementation characteristics are also associated with provider attitudes toward EBPs therefore tailoring implementation strategies may improve provider attitudes (Barnett et al., 2017). Additional research on the mechanism of implementation strategies is needed to understand the contributions of implementation strategies to implementation outcomes, leveraging models such as the theory of planned behavior as a frame (Burgess et al., 2017; Ingersoll et al., 2018). Existing literature suggests that the specific implementation strategy components, such as training that contains consultation with feedback leads to increased clinician skill development (Miller et al., 2004; Sholomskas et al., 2005) and client outcomes (Monson et al., 2018).

Limitations

Despite the many strengths (e.g., a large sample size), limitations warrant mention. First, the models examined were just identified, so fit statistics could not be examined, and remain for future work (e.g., the degree to which models presented are the best representation of the data). To avoid overparameterization of the models, we did not examine how specific aspects of attitudes (i.e., specific subscales on the EBPAS) were related to change in attitudes and competency. Second, there were high levels of missing data for several demographic variables, especially for race and ethnicity. Given that these data were collected in the context of participants’ place of employment, it is possible that participants perceived these questions to be about sensitive information and that they therefore chose to not respond. Furthermore, participants who did not identify as White or Black were less likely to complete assessment measures at the 6-month follow-up. This makes it unclear whether the findings would generalize to samples with differing racial and ethnic composition. Third, generalizability is also limited by the fact that participants in this study were required to participate in the CBT training as part of their organization; however, mental health organizations and systems are increasingly requiring their providers to learn and implement EBPs, creating contexts in which learners may not have self-selected for participation. Given that public mental health systems provide a large proportion of the mental health services in the United States—particularly for economically disadvantaged and historically marginalized groups (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2019)—the findings may generalize to other public systems undertaking similar EBP implementation initiatives.

Future directions

Future research should examine implementation strategies to maximize the return on investment of training dollars, such as by improving less positive trainee attitudes prior to training or by prioritizing trainees based on (more positive) attitudes toward EBPs at baseline. Future studies would benefit from examining potential third variables in the relationship between attitudes and competence. For example, do organizational factors affect the relationships? (Aarons & Sawitsky, 2006). If specific organizational factors influence the association between attitude and competence, this opens the door to studies of the organizational factors that potentiate training and implementation outcomes. Furthermore, the use of CBT was not measured in this study. CBT use could be a mechanism through which attitudes toward EBPs exert their influence on competence. Clinicians with more positive attitudes toward EBPs may be likely to use CBT during training, which may allow them to build more skill in delivering CBT. Similarly, clinician self-efficacy or confidence in their ability to competently implement CBT may also be an important variable to assess. Clinicians with more positive attitudes toward EBPs may have higher self-efficacy (Pace et al., 2020). Given that previous literature has found that change in knowledge of CBT is associated with improvements in EBP attitudes (Lim et al., 2012), an examination of clinicians’ change in knowledge may shed additional light on the relation between attitudes and competence. Future implementation efforts may benefit from directly targeting clinician attitudes toward EBPs prior to training. Targeting specific predictors of skill acquisition, like learners’ attitudes toward EBPs, may be more successful than more broad-based training strategies.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a contract with the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and disAbility Services (Creed, PI) and an NIMH grant (F31MH124346) to Mrs Crane.

ORCID iDs: Torrey A Creed  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0860-2498

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0860-2498

Philip C Kendall  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7034-6961

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7034-6961

Shannon Wiltsey Stirman  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9917-5078

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9917-5078

References

- Aarons G. A. (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research, 6(2), 61–74. 10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024351.12294.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons G. A. (2006). Transformational and transactional leadership: Association with attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services, 57(8), 1162–1169. 10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons G. A., Glisson C., Hoagwood K., Kelleher K., Landsverk J., Cafri G. (2010). Psychometric properties and U.S. national norms of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 356–365. 10.1037/a0019188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons G. A., Green A. E., Miller A. E. (2012). Researching readiness for implementation of evidence-based practice: A comprehensive review of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). In Kelly B., Perkins D. F. (Eds.), Handbook of implementation science for psychology in education (pp. 150–163). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aarons G. A., Hurlburt M., Horwitz S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons G. A., McDonald E. J., Sheehan A. K., Walrath-Greene C. M. (2007). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS) in a geographically diverse sample of community mental health providers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 34, 465–469. 10.1007/s10488-007-0127-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons G. A., Sawitsky A. C. (2006). Organizational culture and climate and mental health provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychological Services, 3(1), 61–72. 10.1037/1541-1559.3.1.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis M. E., Krasnow A. D. (2000). A national survey of practicing psychologists’ attitudes towards psychotherapy treatment manuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 331–339. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett M., Brookman-Frazee L., Regan J., Saifan D., Stadnick N., Lau A. (2017). How intervention and implementation characteristics relate to community therapists’ attitudes toward evidence-based practices: A mixed methods study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44, 824–837. 10.1007/s10488-017-0795-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman S. K., Schneiderman R. L., Zoloth E. (2017). Building an evidence base for effective supervision practices: An analogue experiment of supervision to increase EBT fidelity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 293–307. 10.1007/s10488-016-0723-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T. (1964). Thinking and depression: Theory and therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 10, 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas R. S., Edmunds J., Ditty M., Watkins J., Walsh L., Marcus S., Kendall P. (2014). Are inner context factors related to implementation outcomes in cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth anxiety? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(6), 788–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas R. S., Marcus S., Aarons G. A., Hoagwood K. E., Schoenwald S., Evans A. C., Hurford M. O., Hadley T., Barg F. K., Walsh L. M., Adams D. R., Mandell D. S. (2015). Predictors of community therapists’ use of therapy techniques in a large public mental health system. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, 169(4), 374–382. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimhall K. C., Fenwick K., Farahnak L. R., Hurlburt M. S., Roesch S. C., Aarons G. A. (2016). Leadership, organizational climate, and perceived burden of evidence-based practice in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(5), 629–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess A. M., Chang J., Nakamura B. J., Izmirian S., Okamura K. H. (2017). Evidence-based practice implementation within a theory of planned behavior framework. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 44(4), 647–665. 10.1007/s11414-016-9523-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J. M., Dinnen S., Thompson R., Ruzek J., Coyne J. C., Schnurr P. P. (2015). A quantitative test of an implementation framework in 38 VA residential PTSD programs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(4), 462–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J. M., Dinnen S., Thompson R., Simiola V., Schnurr P. P. (2014). Changes in implementation of two evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD in VA residential treatment programs: A national investigation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(2), 137–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed T. A., Frankel S. A., German R. E., Green K. L., Jager-Hyman S., Taylor K. P., Adler A. D., Wolk C. B., Stirman S. W., Waltman S. H., Williston M. A., Sherrill R., Evans A. C., Beck A. T. (2016). Implementation of transdiagnostic cognitive therapy in community behavioral health: The Beck Community Initiative. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(12), 1116–1126. 10.1037/ccp0000105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed T. A., Stirman S. W., Evans A. C., Beck A. T. (2014). A model for implementation of cognitive therapy in community mental health: The Beck Initiative. The Behavior Therapist, 37, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farahnak L. R., Ehrhart M. G., Torres E. M., Aarons G. A. (2020). The influence of transformational leadership and leader attitudes on subordinate attitudes and implementation success. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 27(1), 98–111. 10.1177/1548051818824529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fordham B., Sugavanam T., Edwards K., Stallard P., Howard R., das Nair R., Copsey B., Lee H., Howick J., Hemming K., Lamb S. E. (2021). The evidence for cognitive behavioural therapy in any condition, population or context: A meta- review of systematic reviews and panoramic meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 51, 21–29. 10.1017/S0033291720005292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank H., Kendall P. C., Becker-Haimes E. (2020). Therapist training in evidence-based interventions for mental health: A systematic review of training approaches and outcomes. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 27. 10.1111/cpsp.12330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner B. R., Hunter B. D., Godley S. H., Godley M. D. (2012). Training and retaining staff to competently deliver an evidence-based practice: The role of staff attributes and perceptions of organizational functioning. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 42(2), 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German R. E., Adler A., Frankel S. A., Stirman S. W., Evans A. C., Beck A. T., Creed T. A. (2017). Testing a web-based training and peer support model to build capacity for evidence-based practice in community mental health. Psychiatric Services, 69(3), 286–292. 10.1176/appi.ps.201700029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C., Landsverk J., Schoenwald S., Kelleher K., Hoagwood K. E., Mayberg S., Green P. & Research Network on Youth Mental Health. (2008). Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: Implications for research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(1–2), 98–113. 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C., Williams N. J. (2015). Assessing and changing organizational social contexts for effective mental health services. Annual Review of Public Health, 36, 507–523. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin G., Bélanger-Gravel A., Eccles M., Grimshaw J. (2008). Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: A systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implementation Science, 3, Article 36. 10.1186/1748-5908-3-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S. G., Baldwin S. A., Merced K., Imel Z. E., Atkins D. C., Creed T. A. (2020). The structure of competence: Evaluating the factor structure of the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale. Behavior Therapy, 51, 113–122. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M. J., Elhai J. D., Schmidt L. O. (2007). Trauma professionals’ attitudes toward and utilization of evidence-based practices. Behavior Modification, 31, 732–748. 10.1177/0145445507302877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler S. W., Chapman J. E., Rowland M. D., Halliday-Boykins C. A., Randall J., Shackelford J., Schoenwald S. K. (2008). Statewide adoption and initial implementation of contingency management for substance-abusing adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 556–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell A. D., Kolko D. J., Scudder A. T., Hiegel S. A., Iyengar S., Chaffin M., Mrozowski S. (2015). Protocol for a statewide randomized controlled trial to compare three training models for implementing an evidence-based treatment. Implementation Science, 10, Article 133. 10.1186/s13012-015-0324-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K. E., Olin S. S., Horwitz S., McKay M., Cleek A., Gleacher A., . . . Hogan M. (2014). Scaling up evidence-based practices for children and families in New York State: Toward evidence-based policies on implementation for state mental health systems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(2), 145–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B., Straiton D., Casagrande K., Pickard K. (2018). Community providers’ intentions to use a parent-mediated intervention for children with ASD following training: an application of the theory of planned behavior. BMC Research Notes, 11, Article 777. 10.1186/s13104-018-3879-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isett K. R., Burnam M. A., Coleman-Beattie B., Hyde P. S., Morrissey J. P., Magnabosco J., . . . Goldman H. H. (2007). The state policy context of implementation issues for evidence-based practices in mental health. Psychiatric Services, 58(7), 914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin B. E., Cross G. (2014). From the laboratory to the therapy room: National dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. American Psychologist, 69(1), 19–33. 10.1037/a0033888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kievit R. A., Brandmaier A. M., Ziegler G., van Harmelen A. L., de Mooij S., Moutoussis M., Goodyer I. M., Bullmore E., Jones P. B., Fonagy N. S. P. N., Consortium Lindenberger U., Dolan R. J. (2018). Developmental cognitive neuroscience using latent change score models: A tutorial and applications. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 33, 99–117. 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko D. J., Baumann B. L., Herschell A. D., Hart J. A., Holden E. A., Wisniewski S. R. (2012). Implementation of AF-CBT by community practitioners serving child welfare and mental health: A randomized trial. Child Maltreatment, 17(1), 32–46. 10.1177/1077559511427346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelovich S. L., Monroe-DeVita M., Hughes M., Peterson R., Cather C., Gottlieb J. (2019). Statewide implementation of cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis through a learning collaborative model. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(3), 439–452. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A., Nakamura B. J., Higa-McMillan C. K., Shimabukuro S., Slavin L. (2012). Effects of workshop trainings on evidence-based practice knowledge and attitudes among youth community mental health providers. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(6), 397–406. 10.1016/j.brat.2012.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnabosco J. L. (2006). Innovations in mental health services implementation: A report on state-level data from the US evidence-based practices project. Implementation Science, 11(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh R. K., Barlow D. H. (2010). The dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological treatments: A review of current efforts. American Psychologist, 65(2), 73–84. 10.1037/a0018121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod B. D., Cook C. R., Sutherland K. S., Lyon A. R., Dopp A., Broda M., Beidas R. S. (2021). A theory-informed approach to locally managed learning school systems: Integrating treatment integrity and youth mental health outcome data to promote youth mental health. School Mental Health. 10.1007/s12310-021-09413-1 [DOI]

- McLeod B. D., Cox J. R., Jensen-Doss A., Herschell A., Ehrenreich-May J., Wood J. J. (2018). Proposing a mechanistic model of clinician training and consultation. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(3), Article e12260-19. 10.1111/cpsp.12260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. R., Yahne C. E., Moyers T. B., Martinez J., Pirritano M. (2004). A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 1050–1062. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson C. M., Shields N., Suvak M. K., Lane J., Shnaider P., Landy M., Wagner A. C., Sijercic I., Masina T., Wanklyn S. G., Stirman S. W. (2018). A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of training strategies in cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Impact on patient outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 110, 31–40. 10.1016/j.brat.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace B. T., Song J., Suvak M. K., Shields N., Monson C. M., Stirman S. W. (2020). Therapist self-efficacy in delivering cognitive processing therapy. Cognitive Behavioral Practice. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.08.002 [DOI]

- Powell B. J., Beidas R. S., Rubin R. M., Stewart R. E., Wolk C. B., Matlin S. L., Weaver S., Hurford M. O., Evans A. C., Hadley T. R., Mandell D. S. (2016). Applying the policy ecology framework to Philadelphia’s behavioral health transformation efforts. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 43(6), 909–926. 10.1007/s10488-016-0733-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A., Griffey R., Hensley M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakovshik S. G., McManus F. (2010). Establishing evidence-based training in cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of current empirical findings and theoretical guidance. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(5), 496–516. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48. 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald S. K., Chapman J. E., Sheidow A. J., Carter R. E. (2009). Long-term youth criminal outcomes in MST transport: The impact of therapist adherence and organizational climate and structure. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38(1), 91–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K., Lewis C. C. (2014). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49–59. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R., Clark D. M., Fairburn C. G., Arntz A., Barlow D. H., Ehlers A., Freeston M., Garety P. A., Hollon S. D., Ost L. G., Salkovskis P. M., Williams J. M., Wilson G. T. (2009). Mind the gap: Improving the dissemination of CBT. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(11), 902–909. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw B. F., Elkin I., Yamaguchi J., Olmsted M., Vallis T. M., Dobson K. S., Lowery A., Sotsky S. M., Watkins J. T., Imber S. D. (1999). Therapist competence ratings in relation to clinical outcome in cognitive therapy of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(6), 837–846. 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas D. E., Syracuse-Siewert G., Rounsaville B. J., Ball S. A., Nuro K. F., Carroll K. M. (2005). We don’t train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(1), 106–115. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. D., Manfredo I. T. (2011). Frontline counselors in organizational contexts: A study of treatment practices in community settings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 41, 124–136. 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2019—Data on mental health treatment facilities. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-mental-health-services-survey-n-mhss-2019-data-mental-health-treatment-facilities

- Swales M. A., Taylor B., Hibbs R. A. (2012). Implementing dialectical behaviour therapy: Programme survival in routine healthcare settings. Journal of Mental Health, 21(6), 548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams N. J., Glisson C. (2014). The role of organizational culture and climate in the dissemination and implementation of empirically supported treatments for youth. In Beidas R. S., Kendall P. C. (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices in child and adolescent mental health (pp. 61–81). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltsey Stirman S., Kimberly J., Cook N., Calloway A., Castro F., Charns M. (2012). The sustainability of new programs and innovations: A review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implementation Science: IS, 7, 17. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk C. B., Becker-Haimes E. M., Fishman J., Affrunti N. W., Mandell D. S., Creed T. A. (2019). Variability in clinician intentions to implement specific cognitive-behavioral therapy components. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), Article 406. 10.1186/s12888-019-2394-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Journal of the American Medical Association, 310(20), 2191–2194. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J., Beck A. T. (1980). Cognitive therapy scale: Rating manual [Unpublished manuscript]. Center for Cognitive Therapy. [Google Scholar]