Abstract

Numerous assays have been described for the detection of DNA and rRNA sequences that are specific for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Although beneficial to initial diagnosis, such assays have proven unsuitable for monitoring therapeutic efficacy owing to the persistence of these nucleic acid targets long after conversion of smears and cultures to negative. However, prokaryotic mRNA has a typical half-life of only a few minutes and we have previously shown that the presence of mRNA is a good indicator of bacterial viability. The purpose of the present study was to develop a novel reverse transcriptase-strand displacement amplification system for the detection of M. tuberculosis α-antigen (85B protein) mRNA and to demonstrate the use of this assay in assessing chemotherapeutic efficacy in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. The assay was applied to sequential, noninduced sputum specimens collected from four patients: 10 of 11 samples (91%) collected prior to the start of therapy were positive for alpha-antigen mRNA, compared with 1 of 8 (13%), 2 of 8 (25%), 2 of 8 (25%), and 0 of 8 collected on days 2, 4, 7, and 14 of treatment, respectively. In contrast, 39 of 44 samples (89%) collected on or before day 14 were positive for α-antigen DNA. The loss of detectable mRNA corresponded to a rapid drop over the first 4 days of treatment in the number of viable organisms present in each sputum sample, equivalent to a mean fall of 0.43 log10 CFU/ml/day. Analysis of mRNA is a potentially useful method for monitoring therapeutic efficacy and for rapid in vitro determination of drug susceptibility.

The continued worldwide dominance of tuberculosis as a cause of morbidity and mortality (22) has fueled extensive research into more rapid and reliable means of diagnosis. Numerous systems for the amplification DNA or rRNA target sequences that are specific for members of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex have been described (9, 14, 16, 23, 25, 27). However, while useful in reducing the amount of time required for definitive diagnosis, these techniques have not been applied successfully in the role of monitoring therapeutic efficacy.

Typically, successful treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis results in conversion of smears and cultures to negative within 2 to 3 months (5). Recently, we have demonstrated that DNA-based amplification assays are an inappropriate substitute for conventional microbiological methods of patient follow-up, since amplifiable nucleic acid may persist for long periods beyond the point of smear and culture conversion (6, 12, 13). Similarly, in patients receiving antituberculosis therapy, a poor correlation has been observed between the results of microscopy or growth-based detection of M. tuberculosis and those of assays for mycobacterial 16S rRNA (10, 19).

However, in contrast to DNA and rRNA, bacterial mRNA is typically short-lived, with a half-life of only a few minutes (2, 26). Consequently, an mRNA-based assay is likely to detect only living organisms and thus be a good indicator of therapeutic efficacy and/or susceptibility to antibacterial agents. We have previously described a method for the efficient recovery of mycobacterial RNA from clinical specimens, as well as the use of reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR assays to detect specific RNA targets (7). The objectives of the present study were to develop a novel RT-strand displacement amplification (SDA) assay for the mRNA that encodes the M. tuberculosis complex alpha-antigen (α-antigen), also known as 85B protein, and to determine whether such an assay could provide a useful alternative to conventional means of patient follow-up in the treatment of tuberculosis. The α-antigen target was selected because this protein is known to be produced in abundance by M. tuberculosis both in broth cultures and in human mononuclear phagocytes (11, 18, 28). The α-antigen may comprise up to 41% of the protein in culture supernatants, and it is reasonable to predict that viable cells will possess a corresponding abundance of the encoding mRNA. Here we describe the application of the RT-SDA assay, together with a thermophilic SDA (tSDA) assay for α-antigen DNA, to sequential sputum specimens from four patients receiving treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

tSDA for α-antigen DNA.

tSDA was performed in 50-μl volumes as follows. Target DNA was added to buffer containing (final concentrations) 52.5 mM K1PO4 (pH 7.6); 12% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); 7.7% glycerol; 500 nM SDA primers S1 and S2; 50 nM bumper primers B1 and B2 (Table 1); 0.2 mM dATP, dGTP, and dUTP; 0.8 mM 2′-deoxycytosine-5′-O-(1-thiotriphosphate); 500 ng of human placental DNA; and 5 μg of acetylated bovine serum albumin. Tubes were heated at 95°C for 2.5 min to denature the target and cooled to 45°C, and 1 U of uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG) was added to facilitate removal of contaminating amplicons. Incubation was continued at 45°C for 10 min before transfer to a heat block at 52.5°C and addition of 40 U of BsoBI, 15 U of exonuclease-deficient Bst polymerase (both from New England Biolabs), 4 U of UDG inhibitor, and 7 mM (final concentration) magnesium acetate. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 45 min, and reactions were terminated by heating at 95°C for 3 min.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences for tSDA and RT-SDA of M. tuberculosis complex α-antigen DNA and mRNA

| Primer name | 5′-to-3′ sequence | Positiona |

|---|---|---|

| SDA primers | ||

| S1 | CgA TTC CgC TCC AgA CTT CTC ggg TTT gTC CgC CAA CAg g | 445–459 |

| S2 | ACC gCA TCg AgT ACA TgT CTC ggg TTT gAC AAg CCg ATT gCA g | 497–482 |

| Bumper primersb | ||

| B1 | ACC TTC CTg ACC AgC gAg | 415–432 |

| B2 | AgA TCA TTg CCg ACg AgC | 523–506 |

| B3 | gCT ggg ggT ggT Agg C | 544–529 |

| B4 | CCg ACA gCg AgC Cg | 571–558 |

| Detector primer D1 | CgC TgC Cgg Tgg gCT TCA Cg | 481–462 |

| Chemiluminescence assay primers | ||

| C1 | gCT TCA Cgg CCC T-(BBB)c | 469–457 |

| AP1 | CgC TgC Cgg Tgg-(AP)d | 481–470 |

Position within α-antigen sequence of M. tuberculosis strain Erdman (8).

BsoBI recognition sequences are in boldface. SDA primer target binding regions are underlined.

B, biotin.

AP, alkaline phosphatase.

RT-SDA for α-antigen mRNA.

Reverse transcription was performed in 20-μl volumes as follows. Target RNA was added to buffer containing (final concentrations) 30 mM K1PO4 (pH 7.6); 12% DMSO; 12.5% glycerol 1,250 nM SDA primer S2; 125 nM bumper primer B2; 12.5 nM B3; 1.25 nM B4 (Table 1); 300 ng of human placental DNA; 5 μg of acetylated bovine serum albumin; 0.2 mM dATP, dGTP, and dUTP; 0.8 mM 2′-deoxycytosine-5′-O-(1-thiotriphosphate); 1 U of PRIME RNase inhibitor (5 Prime-3 Prime, Inc.); and 1 U of UDG. Use of three primers in the reverse transcription reaction mixture was designed to take advantage of the strand displacement activity of avian myeloblastosis virus RT (4) and facilitate the synthesis of multiple copies of cDNA from a single mRNA target molecule. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 45°C for 15 min to facilitate removal of contaminating amplicons by the UDG enzyme before addition of 4 U of UDG inhibitor and 2.5 U of avian myeloblastosis virus RT (Boehringer Mannheim). Tubes were incubated for a further 15 min at 45°C before being equilibrated at 52.5°C for 3 min. SDA was then initiated at the same temperature in a final volume of 50 μl through addition of K1PO4, DMSO, primers S1 and B1, nucleotides, human placental DNA, magnesium acetate, BsoBI, and Bst polymerase to the final concentrations given above for the tSDA DNA assay. Amplification was carried out for 45 min, and reactions were stopped by heating at 95°C for 3 min. Parallel reactions were performed with all clinical samples without addition of RT in order to monitor for DNA contamination of RNA extracts.

Detection of tSDA and RT-SDA products.

The products of amplification were detected by primer extension or chemiluminescence assay. Primer extension analysis was performed with a 32P-labeled D1 probe (Table 1) and exonuclease-deficient Klenow polymerase. Specific oligonucleotide products of 43 and 62 bases were generated which were visualized by autoradiography following electrophoretic separation through 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Chemiluminescent detection of tSDA and RT-SDA products was done with streptavidin-coated microtiter plates as previously described (24), by using a biotinylated capture probe and an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated detector probe (C1 and AP1, respectively; Table 1) which hybridize to the SDA amplicon in the intervening region between primers S1 and S2. SDA samples were diluted 1:10 in 50 mM K1PO4 (pH 7.6) prior to mixing with the capture and detector probes. Readings were taken by using a Labsystems Luminoskan luminometer, and all wells that gave values fivefold higher than the background were considered positive. This cutoff value was determined empirically by comparison of chemiluminescence data with the results of primer extension analysis. Background readings were determined for each assay run by using dummy reaction mixtures containing all of the components of a tSDA reaction except M. tuberculosis target DNA.

Amplification controls.

Positive controls for tSDA of α-antigen DNA comprised reaction mixtures containing known amounts of purified DNA from M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Initial experiments with the RT-SDA system employed positive controls containing in vitro mRNA transcripts generated from a partial clone of the M. tuberculosis α-antigen gene. This clone comprised the central 584-bp EcoRV-SacII fragment of the α-antigen gene ligated into pBlueScript KS+ (Stratagene). In vitro transcripts were generated from the T3 RNA polymerase promoter by using an Ambion MEGAscript T3 Kit in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Later experiments were performed by using transcripts derived from a full-length copy of the M. tuberculosis α-antigen gene (11) cloned into the EcoRV site of the pBlueScript vector. No difference in analytical sensitivity was observed when transcripts derived from either the full-length or partial α-antigen clones were used. Negative controls contained all of the components necessary for DNA or RNA amplification with the addition of either water or target diluent (10-ng/μl yeast carrier RNA [Ambion] or human placental DNA).

Primer specificity.

tSDA reactions were performed as described above, on purified DNA that was isolated from a representative panel of 31 organisms belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex. The S1, S2, B1, and B2 primer set was also tested for cross-reactivity with DNAs from 10 other species of mycobacteria and five closely related genera.

Analytical sensitivity.

To determine the analytical sensitivities of the tSDA and RT-SDA assays, dilutions of purified M. tuberculosis H37Rv DNA and full-length in vitro transcripts of the α-antigen gene were amplified and detected by chemiluminescence assay. Results obtained by chemiluminescence assay were confirmed by primer extension analysis with a 32P-labeled D1 probe.

Control cultures for nucleic acid extraction.

M. tuberculosis H37Rv was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (strain 27294). All cultures were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Liquid cultures were grown in Dubos broth containing 10% Dubos medium albumin (both from Difco) and 0.1% Tween 80. Viable counts were performed by preparing serial 10-fold dilutions of cells in fresh broth and plating them on Dubos agar containing 10% Dubos oleic albumin complex (both from Difco) and 0.1% Tween 80. As a control for the efficiency of nucleic acid extraction, an aliquot of cultured cells was processed with each batch of clinical samples.

Nucleic acid extraction.

Bacteria were lysed by using a FastPrep FP120 cell disrupter with Blue FastRNA Tubes (both from Bio 101), and RNA was isolated by using a modified guanidine-acid phenol procedure (8). DNA was recovered from the same samples by back extraction of the interface and organic layers with a basic salt solution (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and then precipitated with isopropanol (7). Extracted RNA and DNA were resuspended in 100 μl of sterile distilled water.

In order to demonstrate the efficiency of nucleic acid recovery by using the guanidine-phenol extraction procedure, DNA and RNA were isolated from a logarithmically growing culture of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Five-hundred-microliter aliquots of a culture containing 1.23 × 106 CFU/ml were processed as described above, and the relative yields of RNA and DNA were estimated by amplifying serial fourfold dilutions of the recovered nucleic acid.

Patients and specimens.

Sequential noninduced sputum samples were obtained from four patients with newly diagnosed, smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis who attended the Hospital Universitario Cassiano Antonio de Morase, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Brazil. Three specimens were collected on the day treatment was initiated (day 0) with a standard four-drug antituberculosis regimen comprising isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Subsequently, duplicate specimens were collected on days 2, 4, 7, 14, and 30. Samples were homogenized with 2.5% N-acetyl-l-cysteine and glass beads as previously described (7) and 0.5-ml aliquots were frozen at −70°C for nucleic acid extraction. Additional aliquots were decontaminated with NaOH-sodium citrate and plated on selective solid medium for quantitative culture (6). DNA and RNA were prepared from thawed specimens as described above.

RNA extracts of clinical samples frequently contained low levels of M. tuberculosis DNA. To prevent subsequent amplification, the extendable 3′ ends of contaminating DNA molecules were blocked by incubation with dideoxynucleotide triphosphates and DNA polymerase. In brief, RNA extracts from clinical samples were diluted 1:10 in 10-ng/μl yeast RNA, and 5 μl was then added to a mixture containing (final concentrations) 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM magnesium chloride, 25 μM each dideoxynucleotide triphosphate (ddATP, ddCTP, ddGTP, and ddTTP), 5 U of exonuclease-deficient Klenow DNA polymerase, and 1 U of PRIME RNase inhibitor. Mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and diluted either 1:4 or 1:40 in 10-ng/μl yeast carrier RNA or human placental DNA prior to reverse transcription. Dilution of the target RNA was necessary in order to obtain a titration of signal over the course of therapy. To permit comparison, DNA extracts were diluted in a similar fashion prior to amplification. Separate experiments demonstrated that treatment of RNA extracts with dideoxynucleotides under the above-described conditions did not adversely affect the analytical sensitivity of the RT-SDA assay (data not shown).

RESULTS

Primer specificity.

DNAs from 24 isolates of M. tuberculosis from North and South America, Asia, Africa, and Europe were tested in tSDA reactions using primers S1, S2, B1, and B2. All yielded specific products by primer extension analysis with the 32P-labeled D1 probe, as did four North American isolates of M. bovis (including two of human origin), M. bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin (Glaxo strain), and one strain each of M. africanum and M. microti (data not shown).

No significant cross-reaction was observed among 36 strains of nontuberculous mycobacteria comprising 10 isolates of M. avium-M. intracellulare, 7 of M. fortuitum 5 of M. xenopi, 4 of M. malmoense, 3 of M. kansasii, 3 of M. chelonei, and 1 each of M. scrofulaceum, M. gordonae, M. abscessus, and M. celatum. Similarly, no cross-reaction was detected with the phylogenetically related organisms Actinomyces israeli, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Nocardia braziliensis, Rhodococcus rhodochrous, and Streptomyces albus.

Analytical sensitivity.

The analytical sensitivities of the tSDA and RT-SDA assays were determined by amplifying dilutions of purified M. tuberculosis H37Rv DNA and full-length in vitro transcripts of the α-antigen gene, respectively (Fig. 1). Results obtained by chemiluminescence assay were confirmed by primer extension analysis with the 32P-labeled D1 probe (data not shown). The analytical sensitivities of the two assays were similar, on the order of 10 copies of target nucleic acid. For the tSDA assay, two of three reaction mixtures containing two input targets were also positive, as was one of three RT-SDA reaction mixtures. No signal was detected from RT-SDA reaction mixtures prepared without addition of RT.

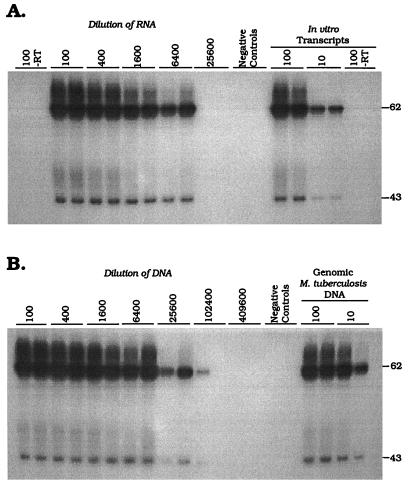

FIG. 1.

Demonstration of the analytical sensitivity of the α-antigen RT-SDA mRNA (A) and tSDA DNA (B) assays. Serial dilutions of full-length in vitro transcripts of the α-antigen gene and purified M. tuberculosis genomic DNA were amplified, and the products were detected by chemiluminescence assay after dilution in K1PO4 buffer. Reactions which gave readings of greater than or equal to five times the background were considered positive. Results represent the mean of three RT-SDA or tSDA reactions. Error bars are standard deviations. Both assays have an analytical sensitivity of ≤10 targets. No product was detected in RT-SDA reaction mixtures prepared without addition of RT.

Nucleic acid extraction.

In order to demonstrate the efficiency of nucleic acid recovery by the guanidine-phenol extraction procedure, DNA and RNA were isolated from a logarithmically growing culture of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. In Fig. 2A, a signal was detected at a 1/6,400 dilution of the recovered RNA. No signal was obtained from reaction mixtures prepared with the 1/100 dilution of RNA in the absence of RT, indicating that the extracted RNA was free of contamination with M. tuberculosis DNA. Figure 2B shows the results obtained by amplifying dilutions of DNA isolated from the same culture sample. Both of the tSDA reaction mixtures prepared with DNA at a dilution of 1/25,600 were positive, as was one reaction mixture prepared with a dilution of 1/102,400. Given that the tSDA and RT-SDA assays have similar analytical sensitivities (above), these data indicate an approximately fourfold greater efficiency of recovery of DNA than RNA. This observation was consistent between replicate extractions of cultured M. tuberculosis (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Titration of α-antigen mRNA (A) and DNA (B) isolated from 6.15 × 105 CFU of cultured M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Amplification products were detected by primer extension with the 32P-labeled D1 probe. The molecular sizes of the full-length and nicked product forms are indicated in bases on the right. α-Antigen mRNA titrated out at a dilution of 1/6,400, whereas both replicates where positive at a dilution of 1/25,600 for the DNA assay. One tSDA reaction mixture was also weakly positive at a dilution of 1/102,400. No product was detected in RT-SDA reaction mixtures prepared without RT, indicating an absence of amplifiable α-antigen DNA from the RNA extract.

Amplification of DNA and mRNA from sputum.

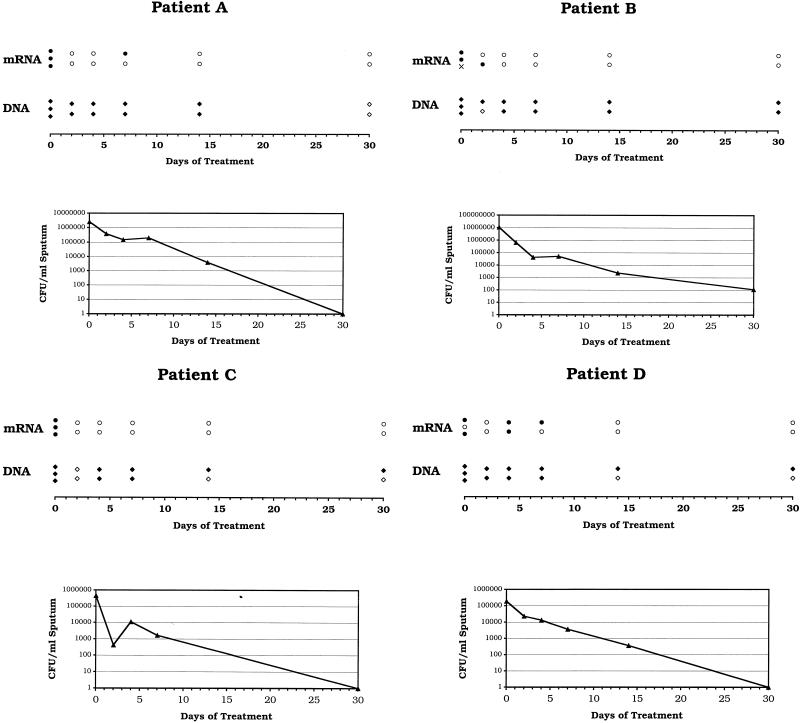

A graphical representation of the α-antigen DNA and mRNA profiles of all four patients included in this study is depicted in Fig. 3. Also shown are the numbers of viable organisms present per milliliter of sputum at each time point. At the dilutions tested, all (100%) of 12 samples collected on the day treatment was initiated (day 0) were positive for α-antigen DNA, compared with 10 (91%) of 11 which were positive for α-antigen mRNA. One RNA sample from patient B on day 0 was contaminated with low levels of α-antigen DNA, as demonstrated by the detection of specific amplification products in RT-SDA reaction mixtures prepared without addition of RT. Thirty-nine (89%) of 44 samples collected on or before day 14 of treatment were positive for α-antigen DNA, compared with 15 (35%) of 43 that were mRNA positive. Three of four patients remained positive for α-antigen DNA on day 30 of treatment, yet all were negative for α-antigen mRNA by day 14. The rapid decline in the number of mRNA-positive samples corresponded to a marked fall in the number of viable organisms present in each sputum sample. Colony counts fell by a mean of 1.72 log10 CFU/ml over the first 4 days of treatment (equivalent to 0.43 log10 CFU/ml/day) but by only a further 1.39 log10 CFU/ml over the next 10 days (0.14 log10 CFU/ml/day). The mean fall in colony counts over the first 2 days of treatment was 0.97 log10 CFU/ml (0.49 log10 CFU/ml/day), but this value is somewhat distorted by an aberrant low viable count on day 2 from patient C (Fig. 3). Three (75%) of the four patients became culture negative for M. tuberculosis by day 30; the remaining patient (Fig. 3, patient B) was culture negative on day 60 of treatment.

FIG. 3.

Graphical depiction of the α-antigen mRNA and DNA profiles of four pulmonary tuberculosis patients during the first 30 days of treatment with a standard four-drug chemotherapeutic regimen. Quantitative culture results are also shown. RNA and DNA extracts were diluted either 1:400 (patients A and B) or 1:40 (patients C and D) prior to amplification, depending on the yield of nucleic acid obtained on day 0. In all four cases, α-antigen mRNA cleared faster than DNA, corresponding to an initial rapid drop in the number of viable organisms (CFU) present per milliliter of sputum. Amplification results: open symbols, negative; closed symbols, positive; ×, undetermined (RNA sample contaminated with α-antigen DNA).

DISCUSSION

The objectives of the present study were to develop a novel RT-SDA system for the detection of M. tuberculosis α-antigen mRNA and to demonstrate the usefulness of this assay in assessing chemotherapeutic efficacy in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. The advent of rapid molecular assays for the detection of specific nucleic acid sequences has decreased the amount of time required for definitive diagnosis of tuberculosis to as little as 1 day. Such assays have found wide application in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis yet have not proven suitable for monitoring the response of patients to treatment owing to the persistence of amplifiable DNA and rRNA target sequences beyond the point of smear and culture conversion (6, 10, 13, 19). This presumably reflects both the shedding of dead or dormant bacilli from pulmonary lesions and the inherent stability of bacterial DNA and rRNA. The American Thoracic Society recommends that the response to antituberculosis chemotherapy of patients bacteriologically positive should be evaluated by repeated examination of sputum at monthly intervals until sputum conversion is documented (1). Owing to the slow growth rate of M. tuberculosis, this is, however, a very inefficient means of assessing treatment efficacy, and the ability to apply molecular assays in this role is desirable. Clinical trials of novel antituberculosis drugs or drug combinations are currently a protracted and prohibitively expensive undertaking, and a rapid method for determining therapeutic response or predicting clinical outcome would be particularly valuable.

In contrast to DNA and rRNA, bacterial mRNA is believed to be short-lived, with a typical half-life of only a few minutes (2, 26). As a result, an assay directed toward an mRNA target is likely to detect only living organisms and therefore be a good marker of bacterial viability and susceptibility to chemotherapeutic agents. Indeed, we have previously described the use of a quantitative RT-PCR system to discriminate between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains in vitro (12). In the present study, we developed an RT-SDA assay directed toward the mRNA encoding the M. tuberculosis complex α-antigen, one of the most abundantly expressed proteins produced by M. tuberculosis (11, 18, 28). The assay was shown to be specific for members of the M. tuberculosis complex and to have a reproducible analytical sensitivity of 10 in vitro transcripts of the α-antigen gene.

In order to demonstrate the ability of the RT-SDA assay to discriminate between live and dead bacilli and its potential as a means to monitor therapeutic efficacy, we conducted a small clinical trial in which the assay was applied to sequential sputum specimens from patients receiving treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. The results from the RT-SDA assay were compared with those obtained by tSDA of α-antigen DNA isolated from the same samples. The exquisite sensitivity of the two assays necessitated dilution of the nucleic acid extracts prior to amplification in order to obtain a titration of DNA and RNA signals over the course of treatment. In all four patients studied, we observed a rapid decline in the number of mRNA-positive samples. At the dilutions tested, no mRNA was detected in any sample beyond day 7 of treatment, whereas all four patients remained DNA positive on day 14 and all but one were also positive on day 30. We have interpreted this as being indicative of the early bactericidal activity of the treatment regimen which was consistent with that seen in other studies which employed an isoniazid-containing treatment regimen (15, 17).

This interpretation of the data is based upon our observation that both the α-antigen DNA and mRNA assays have similar analytical sensitivities. However, we also found that the yield of DNA obtained from cultured cells by using the guanidine-phenol extraction procedure was approximately fourfold higher than that of RNA. This is attributable to the greater inherent stability of DNA over mRNA and to losses incurred through the repeated organic extractions involved in the RNA isolation procedure (7). The greater efficiency of recovery of DNA over RNA probably contributes to the apparent persistence of DNA during the course of treatment in our study. Nevertheless, the decline in mRNA levels did correspond to the rapid fall in colony counts during the first few days of treatment. Clearly, a much larger number of patients needs to be evaluated to confirm these observations, yet these results are consistent with those we obtained in an analysis of α-antigen mRNA levels in cultures of M. tuberculosis exposed to isoniazid and rifampin (12). We are currently investigating the possibility of converting the RT-SDA and tSDA assays described here to a quantitative format (21) which would preclude the need for dilution of the nucleic acid samples prior to amplification and permit direct comparison of RNA and DNA levels between successive samples.

All of the patients included in this pilot study responded to treatment, as determined by both conventional culture and molecular analysis. As a result, it is unclear how drug resistance, in particular, resistance to drugs other than rifampin, would influence a patient’s mRNA profile. Rifampin blocks transcription by directly binding to the β subunit of the RNA polymerase (3, 20), and in vitro studies have shown a much more rapid decline in mRNA levels in rifampin-treated cultures than in those treated with isoniazid (12). It is therefore possible that in patients receiving a multidrug treatment regimen, susceptibility of M. tuberculosis to rifampin could mask resistance to one or more of the other antituberculosis drugs. Nevertheless, failure to observe a downward trend in mRNA levels following the initiation of treatment would be indicative of inappropriate therapy, emerging drug resistance, or noncompliance. Even under such circumstances, it is likely that mRNA analysis would still provide a more rapid assessment of treatment efficacy than is possible by conventional microbiological means. Quantitative analysis of bacterial molecular targets as surrogate indicators of the response of patients to therapy is likely to be of key importance in future development of novel antituberculosis treatment regimens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a research agreement between the University of Arkansas and Becton Dickinson & Company and by the Tuberculosis Research, Prevention & Control Unit (NIH contract N01-AI45244).

We thank Mary Assaf, Ying Chen, and RaeTreal McRory for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bass J B, Farer L S, Hopewell P C, O’Brien R, Jacobs R F, Ruben F, Snider D E, Thornton G. Treatment of tuberculosis and tuberculosis infection in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1359–1374. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.5.8173779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belasco J G, Nilsson G, von Gabain A, Cohen S N. The stability of E. coli gene transcripts is dependent on determinants localized to specific mRNA segments. Cell. 1986;46:245–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90741-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanchard J S. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:215–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collett M S, Leis J P, Smith M S, Faras A J. Unwinding-like activity associated with avian retrovirus RNA-directed DNA polymerase. J Virol. 1978;26:498–509. doi: 10.1128/jvi.26.2.498-509.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combs D L, O’Brien R J, Geiter L J. USPHS tuberculosis short-course chemotherapy trial 21: effectiveness, toxicity, and acceptability. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:397–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-76-3-112-6-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DesJardin L E, Chen Y, Perkins M D, Teixeira L, Cave M D, Eisenach K D. Comparison of the ABI 7700 system (TaqMan) and competitive PCR for quantification of IS6110 DNA in sputum during treatment of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1964–1968. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.1964-1968.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DesJardin L E, Perkins M D, Teixiera L, Cave M D, Eisenach K D. Alkaline decontamination of sputum specimens adversely affects stability of mycobacterial mRNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2435–2439. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2435-2439.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Wit L, Palou M, Content J. Nucleotide sequence of the 85B-protein gene of Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. DNA Seq. 1994;4:267–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenach K D, Sifford M D, Cave M D, Bates J H, Crawford J T. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum samples using a polymerase chain reaction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1160–1163. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamboa F, Manterola J M, Viñado B, Matas L, Giménez M, Lonca J, Manzano J R, Rodrigo C, Cardona P J, Padilla E, Domínguez J, Ausina V. Direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in nonrespiratory specimens by Gen-Probe Amplified Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Direct Test. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:307–310. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.307-310.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harth G, Lee B-Y, Wang J, Clemens D L, Horwitz M A. Novel insights into the genetics, biochemistry, and immunocytochemistry of the 30-kilodalton major extracellular protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3038–3047. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3038-3047.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hellyer T J, DesJardin L E, Hehman G L, Cave M D, Eisenach K D. Quantitative analysis of mRNA as a marker for viability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:290–295. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.290-295.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellyer T J, Fletcher T W, Bates J H, Stead W W, Templeton G L, Cave M D, Eisenach K D. Strand displacement amplification and the polymerase chain reaction for monitoring response to treatment in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:934–941. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iovannisci D M, Winn-Deen E S. Ligation amplification and fluorescence detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA. Mol Cell Probes. 1993;7:35–43. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1993.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jindani A, Aber V R, Edwards E A, Mitchison D A. The early bactericidal activity of drugs in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121:939–949. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.6.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonas V, Alden M J, Curry J I, Kamisango K, Knott C A, Lankford R, Wolfe J M, Moore D F. Detection and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis directly from sputum sediments by amplification of rRNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2410–2416. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2410-2416.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy N, Fox R, Kisyombe G M, Saruni A O S, Uiso L O, Ramsay A R C, Ngowi F I, Gillespie S H. Early bactericidal and sterilizing activities of ciprofloxacin in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1547–1551. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.6_Pt_1.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee B-Y, Horwitz M A. Identification of macrophage and stress-induced proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Investig. 1995;96:245–249. doi: 10.1172/JCI118028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore D F, Curry J I, Knott C A, Jonas V. Amplification of rRNA for assessment of treatment response of pulmonary tuberculosis patients during antimicrobial therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1745–1749. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1745-1749.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Musser J M. Antimicrobial agent resistance in mycobacteria: molecular genetic insights. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:496–514. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nycz C M, Dean C H, Haaland P D, Spargo C A, Walker G T. Quantitative reverse transcription strand displacement amplification: quantification of nucleic acids using an isothermal amplification technique. Anal Biochem. 1998;259:226–234. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raviglione M C, Snider D E, Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis: morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA. 1995;273:220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah J S, Liu J, Buxton D, Hendricks A, Robinson L, Radcliffe G, King W, Lane D, Olive D M, Klinger J D. Q-Beta replicase-amplified assay for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis directly from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1435–1441. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1435-1441.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spargo C A, Haaland P D, Jurgensen S R, Shank D D, Walker G T. Chemiluminescent detection of strand displacement amplified DNA from species comprising the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Mol Cell Probes. 1993;7:395–404. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1993.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Vliet G M E, Schukkink R A F, van Gemen B, Schepers P, Klatser P R. Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) for the identification of mycobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2423–2429. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-10-2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Von Gabain J, Belasco G, Schottel J L, Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Decay of mRNA in Escherichia coli: investigation of the fate of specific segments of transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:653–657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.3.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker G T, Fraiser M S, Schram J L, Little M C, Nadeau J G, Malinowski D P. Strand displacement amplification—an isothermal, in vitro DNA amplification technique. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1691–1696. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiker H G, Harboe M. The antigen 85 complex: a major secretion product of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:648–661. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.648-661.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]