Abstract

Objective

This work aimed to analyze parental burnout (PB) and establish a comparison between the times before (Wave 1) and during (Wave 2) the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Background

The COVID‐19 pandemic brought additional stress to families. The pandemic could be particularly difficult for parents experiencing parental burnout, a condition that involves four dimensions: an overwhelming sense of exhaustion, emotional distancing from the child, saturation or a loss of fulfillment with the parental role, and a sharp contrast between how parents used to be and how they see themselves now.

Method

A quasi‐longitudinal research design was adopted, comparing two cross‐sectional studies among Portuguese parents (N = 995), with an interval of 2 years between each wave of data collection. Participants were surveyed voluntarily through an online questionnaire located on the institutional web platform of the universities involved in the study. Multivariate analysis of covariance was used to take into account the associations among variables, alongside controlling the possible confounding effects.

Results

Parents have overall higher parental burnout scores in Wave 2 than Wave 1, with increased exhaustion, emotional distancing, and contrast, but decreased saturation. Although parental burnout levels remain higher for mothers across the two Waves, the growth is greater for fathers than for mothers.

Conclusion

Reconciling childcare with paid work is a stressful and new experience for many fathers. However, results suggest that even amid a crisis, some parents had the opportunity to deeply bond with their children.

Implications

We expect this work to encourage stakeholders to consider proper intervention strategies to address potential parental burnout. Also, initiatives that strengthen gender equity within parenting context are needed.

Keywords: COVID‐19, family stress, gender issues, parental burnout, parenting, Portugal

This study aimed to shed light on how mothers and fathers dealt with the lockdown during the state of emergency in Portugal caused by the COVID‐19 pandemic response. On March 2, 2020, the first two cases of COVID‐19 were identified in Portugal. About 2 weeks later, with two deaths and 642 positive cases (Direção Geral de Saúde, 2020), the Portuguese government declared a state of emergency. This meant the closure of all schools, kindergartens, factories, shops, and business in general, except those considered essential (Diário da República Eletrónico [DRE], 2020a). People's movement between locations was restricted; online learning was implemented and working from home was recommended whenever possible. Also, the Portuguese Government created a special financial support scheme for workers with children under 12 years of age, so that parents could remain with their children at home (DRE, 2020a). On May 2, 2020, the unlocking period began and the COVID‐19 restriction measures were gradually alleviated (DRE, 2020b). Daycare centers and kindergartens reopened in June 2020, but all schools maintained online learning until the end of the school year on June 26, 2020, except for 11th‐ and 12th‐grade students, who took some regular lessons to prepare for higher education entrance exams.

One of the impacts of the lockdown measures was the limitation of social contact with extended family, close relatives, and friends. Another striking impact for many families was significant loss of income due to layoff measures or job loss. For parents who had the opportunity to continue their job activities from home, being able to juggle both paid work and caring for the family within the household was a major challenge, especially for those who lived in a low‐income household or were in a situation of vulnerability (Bradbury‐Jones & Isham, 2020; Craig & Churchill, 2020; Usher et al., 2020).

Homes became places for working, as well as for the caring and teaching of young children without the usual help or assistance granted by the extended family, such as grandparents, or collective childcare resources that Portuguese families usually turn to (Prioste et al., 2017; Wall, 2002). In fact, the preschool enrollment rate in Portugal is quite high. In the 2017–2018 school year, 90.1% of children between the ages of 3 and 5 years were enrolled in preschools (Conselho Nacional de Educação, 2019). With the lockdown, families lacked not only institutional support but also extended family support, recognized as a determinant bond both from an affective and instrumental point of view (Portugal, 2011). Indeed, relations between grandparents and grandchildren are highly valued in Portuguese society, assuming important emotional, educational, and instrumental support, in an important form of intergenerational relations and solidarity (Prioste et al., 2017; Ramos, 2012).

Lockdown and Parental Burnout

The COVID‐19 pandemic has brought a number of stressful issues for both parents. With all the family members at home indefinitely, the amount of unpaid family work increased substantially during the lockdown (Craig & Churchill, 2020; McLaren et al., 2020). Unsurprisingly, recent research has been shown an increased risk of distress for both parents and children (Coyne et al., 2020; Griffith, 2020).

It can be demanding for parents to combine the supervision of child(ren)'s homeschooling while trying to work from home. Moreover, for parents who are not working from home, going back and forth to work and the concerns about potential contamination of their homes are additional sources of stress. Overall, parents are doing their best to maintain regular routines in everyday life and to create new learning and entertainment activities for children at home, providing a safe and positive environment to help them express their feelings (Cluver et al., 2020; Coyne et al., 202; Dalton et al., 2020). Often, parents also experience concerns regarding the needs of their elderly parents whom they need to care for at a distance and ensure their safety (Coyne et al., 2020; Griffith, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020).

As a result of all these changes, emotional well‐being has been affected by increased anxiety, loneliness, boredom, fear, sleep disorders, changes in concentration, irritability, and uncertainty about the future, to name a few concern (Gunnel et al., 2020; Röhr, 2020; Vinkers et al., 2020). A survey carried out during the first month of lockdown in Portugal revealed that 82% (n = 160,157) of participants reported feeling anxious, sad, or angry every day or almost every day (Dias et al., 2020). With the demands faced, these effects may be particularly felt by parents.

Nowadays, parenting can be embedded with parenting norms that pose high and impossible standards because there is a strong social pressure for parents to excel in raising their child (Prikhidko & Swang, 2020). These high standards are a risk factor for parents' stress and burnout (Roskam et al., 2018). In a period of family confinement, this risk is likely heightened, even more so for parents who have already been experiencing difficulties in their parental role (Griffith, 2020). These parents may be at highest risk of burnout. Parental burnout is a condition that involves four key dimensions: an overwhelming sense of exhaustion related to their parental role; emotional distancing from the child(ren), limiting interactions to functional or instrumental issues; saturation or a loss of joy and fulfillment on their parental role, of feeling fed up; and a contrast between how parents used be and how they see themselves acting now as a mother or father (Roskam et al., 2018). It is important to note that parental burnout differs from daily parental stress because it is a prolonged exposure to overwhelming stress related to parenting, with high demands and limited resources. Therefore, parental burnout results from a chronic imbalance of risks over resources (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018).

Hypothesis 1. Because lockdown measures seem to increase the demands on parents, we expect parents to report higher levels of parental burnout in the dimensions mentioned earlier during restrictive pandemic lockdown measures than before.

Gender and Parental Burnout

Although both fathers and mothers are usually full‐time working parents (PORDATA/INE, 2020), gender inequalities in the family sphere are a constant within the Portuguese context. Indeed, even when mothers have a full‐time job or when fathers are unemployed, mothers do the bulk of domestic and childcare work (Aguiar et al., 2020; Matias et al., 2012; Perista et al., 2016). Further, despite the increasing involvement of fathers in childcare, parenthood remains a domain strongly affected by gender inequalities. Additionally, the intensive mothering model prevails in Portuguese society (César et al., 2018), placing high standards on the mother in terms of her total availability, attention, and dedication to the child(ren). As a consequence, mothers who adhere to this model tend to ignore their own needs in an attempt to meet society's expectations and, therefore, are at an increased risk of becoming overwhelmed. As these mothers may always put their children first, they may experience negative feelings more often, such as anxiety, doubt, guilt, sadness, and loneliness (César et al., 2018, 2020). According to the literature, intensive mothering was conceptualized as a series of predominant attitudes among women from the middle to upper classes with a high educational level (Rizzo et al., 2013).

Given this literature, it is unsurprising that research indicates a higher average level of parental burnout among mothers than fathers, explained by social gender roles that reinforce the representation of the mother as the childcare expert while the father remains her assistant (Matias et al., 2020; Roskam & Mikolajczak, 2020). Also, it is important to note that mothers make up 87% of single‐parent families in Portugal, which means in 87% of cases, it is the mother who lives with the children (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2014). Nonetheless, burnout appears to have more severe consequences for fathers' parental role than for mothers' role (Roskam & Mikolajczak, 2020). Specifically, aggressive and neglectful behavior toward children has been reported as more common in fathers experiencing burn out thanin mothers (Mikolajczak et al., 2018; Roskam & Mikolajczak, 2020).

Considering how work and family balance usually plays along traditional gender roles (Matias & Fontaine, 2015; Wall et al., 2016) and also that Portuguese mothers tend to do the bulk of domestic and childcare work in the home (Perista et al., 2016), we expect that this disparity will be aggravated by the pandemic crisis. Although the imposed lockdown required both fathers and mothers to stay at home, this does not mean that they fairly shared their responsibility for family care (Craig & Churchill, 2020; McLaren et al., 2020). This could bring an additional burden, especially for women, and could potentially affect parents' performance as a caregiver. Recent work carried out in 18 countries reveals that COVID‐19 is intensifying the workload of women at home, as they are taking on most household tasks and family care during the pandemic (United Nations Women, 2020). In support of the potential for difference in the impact of the pandemic on families are reports that social calamities (such as war, natural disasters, or past disease outbreaks) often lead women to increased vulnerability, exacerbating gender burdens (Bradshaw & Fordham, 2015; McLaren et al., 2020; Mondal, 2014).

Hypothesis 2. Therefore, in this current study, we expect that mothers and fathers are dealing differently with the changes caused by the COVID‐19 crisis and that with these differences in dealing with pandemic‐related changes, that a greater difference in the fathers reporting levels of burnout prior to the pandemic and fathers reporting during the pandemic in comparison to the difference in levels of burnout reported by mothers prior reporting prior to the pandemic and mothers reporting levels during the pandemic.

Current Study

In this study, our focus is to analyze parental burnout levels, comparing levels of burnout reported by a group of mothers and fathers before confinement to levels reported by a second group during home confinement. To summarize, we expect levels of burnout reported by both mothers and fathers prior to the pandemic restrictive confinement to be significantly lower than the levels reported during the pandemic by a second group of parents (Hypothesis 1). Second, we expect gender differences in parental burnout, with higher levels of women's burnout (Hypothesis 2). Finally, we expect gender differences to be exacerbated by lockdown measures, that is, to be of higher magnitude in Wave 2 (Hypothesis 3).

Method

Research Approach and Design

A quasi‐longitudinal research design was adopted by comparing two cross‐sectional studies among the same specific population (Portuguese fathers and mothers, living with at least one child under the age 18 years), although different individuals were surveyed at each time wave. The time interval between the two periods of data collection was 2 years, that is, in 2018 (pre‐pandemic wave = Wave 1 [W1]) and 2020 (during pandemic lockdown wave = Wave 2 [W2]). This research is part of a larger project, involving more than 40 countries, called International Investigation of Parental Burnout (IIPB).

Participants

Data were collected from a sample of 995 Portuguese parents (406 from W1 and 589 from W2). Participants in both Waves had at least one child who was living at home. In both Waves, 68.3% of participants were mothers (50.5% and 80.8% for W1 and W2, respectively). On average, parents were 41.26 years old (SD = 6.89), the mothers were on average 40.3 years old (SD = 6.26), and the fathers were 43.4 years of age (SD = 8.32). Mean age was 41.8 years (SD = 8.06) for the W1 participants and 40.89 years (SD = 5.96) for the W2 participants. Parents had, on average, 16 years of education (SD = 3.72): W1 parents had 14.86 years (SD = 3.84) and W2 parents had 16.76 years (SD = 3.44) of education. Approximately 85% of participants were part of a two‐parent family, 7.6% were single parents; 4.9% of participants were part of stepfamilies and 1.9% of multigenerational families. Overall, the participants had from one to five children, with 41% with one child and 48% with two. Most of respondents were working parents (93.1% of the W1 and 87.2% of the W2 parents).

Participants from both Waves were compared on sociodemographic variables (gender, age, educational level, marital status, number of biological children, number of children living at home, job occupation) to sustain sample equivalence and to identify possible confounding variables. Samples from W1 and W2 were equivalent in terms of families' living situation (kind of neighborhood), χ2(2) = 1.733, p =.420; number of biological children, t(793,197) = –.621, p = .544; and number of children living at home, t(849,276) = .083, p = .934. As expected, the percentage of working parents was lower during the lockdown situation, χ2(1) = 5.389, p =.020. However, the two samples differed with respect to the proportion of male and female participants, χ2(1) = 12.023, p =.001; as there were more women in W2 than in W1. The samples differed in mean educational levels, t(699) = 3.400, p =.001; with parent's education level being lower in W1 (M = 14.86, SD = 3.84) than W2 (M = 16.76, SD = 3.45). Age of the parents also was different across samples, F(1) = 4.067, p <.044, as parents in W1 were found to be slightly older (M = 41.80, SD = 8.61) than those parents from W2 (M = 40.89, SD = 5.96).

Procedures

This research has the approval of both the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences from the University of Porto (FPCEUP‐CE: 2017/12‐12) and from the Ethics Committee of the Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (CES‐UC: 2020/28‐04).

At both Waves, data were collected through an online survey located at institutional web platforms from the universities involved in the study. According to official data (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2019), approximately 81% of Portuguese households have access to the Internet at home. Thus, the researchers followed advertisements in various Internet pages (e.g., local government pages and school's websites), social media (e.g., Facebook groups aimed at parents), and through professional networks and associations.

Instruments

Parental burnout was measured by Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA; Roskam et al., 2018), adapted and validated to Portuguese by Matias et al. (2020). This instrument has been considered as the gold standard to assess the experience of parental burnout (Aunola et al., 2020). It is composed of 23 items distributed in the previously mentioned four dimensions: emotional exhaustion (nine items), contrast (six items), saturation (five items), and emotional distancing (three items). Cronbach's alphas for the four subscales and the global score were, respectively, .94, .89; .83, .79, and .96 for the W1 and .95, .92, .93, .78, and .97 for W2. The correlation among PBA subscales, both in W1 and W2, is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pearson Correlation Among PBA Subscales

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exhaustion | — | .815** | .935** | .638** |

| 2. Contrast | .817** | — | .872** | .750** |

| 3. Saturation | .714** | .786** | — | .644** |

| 4. Distancing | .705** | .785** | .687** | — |

Note. For Wave 1, values are above the diagonal; for Wave 2, values are displayed below the diagonal.

Sociodemographic data. Respondents provided sociodemographic data regarding their age, level of education, employment situation, type of family, number of children in the household, neighborhood features, and work outside the home. W2 protocol also included specific questions about how families were coping with the COVID‐19 pandemic and the quarantine measures (number of days in lockdown, employment situation during lockdown, changes in family's financial situation).

Data Analysis

Preliminary analyses on skewness and kurtosis were performed to confirm the normal distribution of PBA dimensions and PBA global score, allowing the use of parametric statistical analyses. Values of asymmetry lower than |3| and of kurtosis lower than |10| were considered sufficient to ascertain normal univariate distribution (Kline, 2010). Another assumption for this multivariate analysis is the homogeneity of variance–covariance matrices, in particular when sample sizes are highly divergent as is the case here. The variances and covariances for each group (Wave * gender) showed a ratio inferior to 10:1 and the group with the larger sample (women at W2) produced the larger variance and covariances. Thus, the alpha levels produced are conservative and the null hypotheses can be rejected with confidence (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2012).

Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used to take into account the associations among dependent variables (the four PBA subscale dimensions and total score) and our independent variables (gender and wave), alongside controlling the possible confounding effects of parental education and age that were previously found to vary across waves. To test Hypotheses 1, we compared PBA dimensions and PBA global score between W1 and W2. To test Hypotheses 2 and 3, we included wave and gender as between subject factors (2 × 2).

Results

Analyses of Covariance in Parental Burnout

A MANCOVA with Wave and gender as between‐subjects factors and age and educational level as covariates was conducted. Multivariate analyses (Pillai's trace) identified a significant effect of Wave, F(4, 964) = 66.285, p <.001, ηp2= .216, and of gender, F(4, 964) = 16.337, p <.001, ηp2= .063, as well as a significant interaction effect between wave and gender, F(4, 964) = 7.302, p <.001, ηp2= .029. Also, effects of age, F(4, 964) = 10.418, p <.001, ηp2= .041, and parent's educational level, F(4, 964) = 7.265, p <.001, ηp2= .029, were found significant.

An increase of the levels on three dimensions of the PBA was observed from parents in W1 to parents in W2: exhaustion, emotional distancing, and contrast; conversely, levels of saturation decreased from W1 to W2. Wave differences explained 1% to 3.5% of variance (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Covariance for Wave and Gender (2b)

| Effects | Variables | Wave 1 M (SD) | Wave 2 M (SD) | F | p | h p 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave | Global PB | 20.63 (22.92) | 26.53 (28.13) | .68 | .41 | .001 |

| Exhaustion | 10.85 (11.32) | 15.31 (14.04) | 6.51 | .01 | .007 | |

| Saturation | 4.68 (5.31) | 2.86 (5.69) | 45.76 | .001 | .045 | |

| Distancing | 1.50 (2.37) | 2.29 (3.30) | 6.06 | .01 | .006 | |

| Contrast | 3.60 (5.46) | 6.06 (7.72) | 6.91 | .01 | .007 | |

| Father | Mother | F | p | h p 2 | ||

|

Gender |

Global PB | 13.68 (17.91) | 28.96 (28.19) | 44.31 | .001 | .044 |

| Exhaustion | 7.81 (9.65) | 16.14 (13.76) | 45.26 | .001 | .045 | |

| Saturation | 2.06 (3.55) | 4.30 (6.21) | 47.57 | .001 | .047 | |

| Distancing | 1.34 (2.42) | 2.26 (3.17) | 7.65 | .006 | .008 | |

| Contrast | 2.47 (4.18) | 6.26 (7.68) | 33.59 | .001 | .034 |

Note. PB = parental burnout. Wave 1: N = 391; Wave 2: N = 582. Wave 2b: Father n = 306; Mother n = 667.

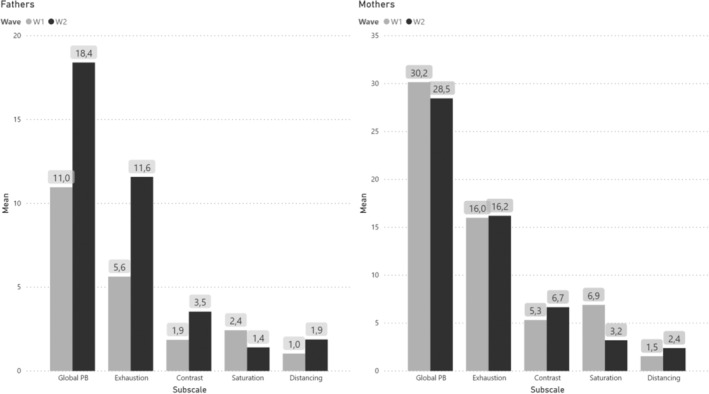

Concerning gender effects, mothers showed higher levels of parental burnout than fathers, in all dimensions, explaining 1% to 6.1% of variation for each dimension. The interaction effect, nonetheless, revealed that these heightened levels from fathers in W1 to fathers in W2 were more pronounced with scores substantially increased from W1 to W2, for exhaustion, whereas mothers' levels remained stable, as shown in the Table 3. Saturation levels decreased for both parents, but the decrease was more pronounced for mothers than for fathers. The increase of parental emotional distancing and contrast from W1 to W2 did not vary according to gender nor did the differences between fathers and mothers vary from W1 to Wave 2 (see Figure 1).

Table 3.

The Multivariate Interaction Effect of Gender and Wave

| Variables | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | F | p | h p 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Global PB |

F | 10.96 (15.27) | 18.40 (20.29) | 2.82 | .093 | .003 |

| M | 30.15 (25.15) | 28.46 (29.38) | ||||

| Exhaustion | F | 5.63 (7.87) | 11.58 (11.22) | 4.86 | .028 | .005 |

| M | 15.99 (11.87) | 16.20 (14.50) | ||||

| Saturation | F | 2.43 (3.49) | 1.41 (3.57) | 7.31 | .007 | .007 |

| M | 6.90 (5.84) | 3.21 (6.04) | ||||

| Distancing | F | 1.04 (2.19) | 1.88 (2.70) | .33 | .564 | .00 |

| M | 1.54 (2.46) | 2.39 (3.42) | ||||

| Contrast | F | 1.86 (3.20) | 3.54 (5.34) | .03 | .867 | .00 |

| M | 5.32 (6.58) | 6.66 (8.07) | ||||

Note. Wave 1: Father (F) n = 194; Mother (M) n = 197. Wave 2: Father n = 112; Mother n = 470.

Figure 1.

Effects of Gender and Wave Interaction

Conclusion

The impact of COVID‐19 has been dramatic worldwide—not just to individuals' health but also to societal and familial functioning. In this article, we focused on the risks associated with COVID‐19–related home confinement for Portuguese parents' burnout, and explored how gender is intertwined with this phenomenon. To achieve this, we compared two groups of parents, one group from before (W1) and one group during (W2) the pandemic lockdown.

Our findings revealed not only significant differences in reported parent burnout by the parents in W1 and W2 for all dimensions but the global score and also that mothers and fathers were different in the before and after pandemic lockdown waves. All dimensions of PB increased from W1 to W2, except for saturation, which decreased. When considering just the gender main effect, gender differences were found regardless of the Wave and parental burnout dimension considered, with mothers having higher levels in all parental burnout dimensions than fathers; however, part of these mean‐level differences are shaped by the interaction with wave. Indeed, exhaustion levels increased significantly for fathers from W1 to W2, whereas they remained unchanged for mothers, and saturation levels decreased more strongly for mothers than fathers. Emotional distancing and contrast are not altered by wave and gender interactions, and, considering only unique effects, those are higher for mothers and in W2.

We therefore, have partially confirmed our first hypothesis, as we found fathers and mothers in W2 reporting higher scores on exhaustion, distancing, and contrast dimensions in comparison with those in W1, after controlled confounding sociodemographic variables. This increase may be linked to an increase of parents' responsibility for all routine family tasks and newly acquired tasks related to the lockdown, such as, homeschooling and work from home, as well as receiving less external support, such as preschool care or schools. Moreover, even for after school activities, Portuguese families generally outsource care either resorting to institutions that offer after‐school activities or grandparents that can help them with the caring, education, and socialization of their child(ren) (Ramos, 2012; Wall, 2002). This outsourcing of afterschool care occurs due to the high rates of full‐time work of both mothers and fathers, as well as to their long workhours. However, during lockdown, all these external sources of support for childcare were limited or nonexistent and parents had to run all family tasks while maintaining their professional performance at home amid a global health crisis.

Another result, however, does not support our first hypothesis: Saturation was the only parental burnout dimension that was lower for both mothers and fathers in the Wave 2 pandemic lockdown. In its definition, saturation entails the feeling that parents no longer enjoy being with their children. The pandemic lockdown has granted parents more opportunities to share time and activities with their children on a daily basis, and this increase in shared time and activities may have allowed them to bond in a manner not previously possible due to the high number of working hours Portuguese parents usually work (Torres et al., 2014). The absence of differences for global parental burnout scores is easily explained because the increase of some of its dimensions may be compensated for by the decrease of another.

In our study, we observed gender differences in all parental burnout indicators, confirming Hypothesis 2. Mothers were more exhausted, more saturated, and more emotionally distant from their children than fathers. Mothers also believed that they used to be a better mother before the pandemic lockdown through which they were living. As a result, a strong effect size was found for mothers' global parental burnout score than for fathers. These results are in line with other studies that highlight the COVID‐19 pandemic as a catalyst that reverberates in gender inequality among heterosexual couples (Craig & Churchill, 2020) with women being more burned out by the persistence of all elements of the nuclear family at home.

Findings also revealed that the impact of pandemic lockdown on mothers and fathers was not the same for some PBA dimensions, and these results did not support our third hypothesis. We had foreseen a worse impact of the pandemic for women than for men because women assume most domestic and parenting responsibilities. However, we observed the opposite. Whereas exhaustion level for mothers reporting in W1 to mothers reporting in W2 was stable men's levels increased substantially. Mothers were more exhausted than fathers, but their exhaustion levels did not increase from that of mothers' before the pandemic. This is not the case for fathers, who felt much more exhausted during the pandemic than in the previous period. These results suggest that wave differences are caused more by the increment of fathers' burnout levels than that of mothers'.

This interesting finding can be understood if we consider how work and family roles usually interplay within the Portuguese family. Women are typically found to have more strain in balancing their work and family roles because they are seen as the irreplaceable caretaker of the family, despite their high involvement in the work sphere as well (Matias, 2019). Indeed, even when women are working at a full‐time job, they perform the bulk of household and childcare tasks (Aguiar et al., 2020; Perista et al., 2016). Further, women's pressure to place their children's needs before their own is higher than it is for men (César et al., 2018). Indeed, past studies show that in parental dyads, women are the ones who are using a greater number and variety of conciliation strategies to balance multiple roles (Matias, 2019; Matias & Fontaine, 2015).

Therefore, the pandemic lockdown brought no surprising demands for women, and the novelty, perhaps, was only its duration; whereas men had, perhaps for the first time, the need to balance simultaneously their work and their family caring, spending more time with children, bearing the cries, shouting, and conflicts, for example. Women had already developed efficient strategies to balance work and family roles, and men may not have had this experience. Thus, women's “past experiences” and the sense of efficacy developed in dealing with such a challenge may have protected them from feeling even more overwhelmed by the demands of the new situation. These new demands may have resulted in an acute sense of exhaustion for men. Because the situation was new for them, the men had no past experiences to rely on and needed to create new strategies. Although men may objectively still do less than their partners, the men felt the parental role has draining their emotional resources as never before. These findings may complement previous research (Roskam & Mikolojczak, 2020) that showed fathers being more likely to burn out even before risks outweighed their resources or because they spend their resources more quickly in these new situations.

In recent years, new forms of involved fatherhood have arisen in Portugal (Wall & Leitão, 2017). Fathers are now expected to be active in caring for their children, and the pandemic lockdown could have been the opportunity for men both to implement this new model of active caring and to feel its consequences, both positively (enjoying time with children) and negatively (feeling exhausted). In fact, the father's saturation level decreased significantly from W1 to W2, even if the mother's saturation level decreased more sharply.

Another alternative explanation is that perhaps a change of mindset has influenced fathers' attitude toward their role as parents. In light of cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957) and in view of the tension between the obligation to stay at home and the difficulties of being a full‐time parent and experiencing negative emotions in this role, parents would seek to reduce such dissonance, changing their personal attitude and framing their time with their children as being more positive or less negative. Following this reasoning, it was possible, for some parents, to enjoy their parental role even while stressed due to lockdown. This assumption, of course, requires further investigation. But the question arises as to whether this secondary gain from the lockdown will remain in the long term after the pandemic crisis, with mothers and fathers resuming their previous family and work routines.

Study Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in the Portuguese context that focuses on parental burnout during the pandemic. Although women were overrepresented in the pandemic‐related second wave and the majority of participants were highly educated parents, our results are informative in relation to furthering understanding of families' experiences of the pandemic response. In this research, to control confounding effects of sociodemographic sample differences, we included gender, educational level, and parent's age as between‐subject factors or covariates in our analyses. However, we are aware that our result cannot be generalized to less educated parents. In future work, it might be important to encompass a broader strategy to recruit parents, particularly men and less educated parents. Further, researchers also should consider adding complementary procedures (such as interviews and observations), as suggested by Blanchard and colleagues (2020). In addition, a dyadic approach addressing parental burnout within the family could highlight compensatory or cumulative processes between parents.

All variables were self‐report measures, with associated memory biases and social desirability factors. Additionally, although having comparable characteristics, Wave 1 and Wave 2 parents were not the same participants in each Wave. In relation to research design, the pandemic context made an online data collection was the safest available option. However, this introduces a limitation that ought to be acknowledged. We were reporting parents' differences on their own perception of reality before and after pandemic lockdown and not more objective indicators of experience.

We expect this work to encourage stakeholders (e.g., family therapists, social workers, and health professionals) to better understand the effects of the COVID‐19 crisis in mental health, such as, for example, increasing parents' stress, especially for fathers, to help practitioners consider parental burnout while working with families. It is important to note that these effects are probably not restricted to the lockdown period but might be extended to the periods after this current crisis (Griffith, 2020). Therefore, further studies are warranted to carefully consider proper intervention strategies toward burned‐out parents.

Implications

Considering that risks and resources theory (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018) postulates that parental burnout is an imbalance between the demands of parents' expectations of themselves and the availability of resources available to meet those expectations or demands, we address some recommendations to practitioners and family therapists. First, it is important to identify, within the constraints imposed by the pandemic, some protective factors that can help parents relieve their stress before it becomes chronic. In addition, it is crucial also to manage parents' expectations of themselves or what they perceive as others' expectations for them because self‐oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism are risk factors for parental burnout (Sorkkila & Aunola, 2020). In fact, if the demands for being a perfect parent is higher even at the best of times, in a time of crisis the resources needed to meet those demands are likely to be insufficient (Griffith, 2020).

Finally, as we mentioned before, for parents who are working from home, while having a greater opportunity to participate in their child(ren)'s daily life, the lack of separation between work and home can become a burden. Therefore, more than ever, coparenting is an important aspect to work on because partners can play a key role in supporting (or undermining) both each other's professional careers and their parental roles. In addition, partners should (re)think division of family tasks because being at home 24 hours a day, 7 days a week offers an unprecedented opportunity to work both to balance work requirements and to increase one's relative contribution to household chores and childcare, creating a fair division of unpaid work between the couple and easing the other's burden.

This study also may contribute to public policies aimed at families during the pandemic and in its aftermath. Policymakers should take into account the importance of mental health prevention strategies for parents, providing open access to online resources (Cluver et al., 2020). Another useful strategy may be to offer remote psychological support to parents, for example, through a helpline operated by psychologists and other mental health professionals. Especially for fathers, who may be more reluctant to share their feelings and concerns with another person, self‐directed parenting interventions displayed in materials such as brochures, e‐books, videos, and mobile apps can be an effective way to offer advice on how to avoid parental burnout during these peculiar times. In addition, initiatives are needed to strengthen gender equity in the context of parenting, such as the PARENT project, which aims to engage men in parenting through the Program P approach and to promote a more equal division of unpaid work. Finally, public policies should consider extended economic support for parents who lost their jobs or were under layoff measures, more flexible work schedules, thus enhancing the work–family support.

References

- Aguiar, J. , Sequeira, C. F. , Matias, M. , Coimbra, S. , & Fontaine, A. M. (2020). Gender and perception of justice in housework division between unemployed spouses. Journal of Family Issues, 42(6), 1217–1233. 10.1177/0192513X20942823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aunola, K. , Sorkkila, M. , & Tolvanen, A. (2020). Validity of the Finnish version of the Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(5), 714–722. 10.1111/sjop.12654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, A. L. , Roskam, I. , Mikolajczak, M. , & Heeren, A. (2020). A network approach to parental burnout . PsyArXiV. 10.31234/osf.io/swqfz [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury‐Jones, C. , & Isham, L. (2020). The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID‐19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 10.1111/jocn.15296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, S. , & Fordham, M. (2015). Double disaster: Disaster through a gender lens. In Collins A. E., Jones S., Manyena B., & Jayawickrama Janaka (Eds.), Hazards, risks and disasters in society (pp. 233–251). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- César, F. , Costa, P. , Oliveira, A. , & Fontaine, A. M. (2018). “To suffer in paradise”: Feelings mothers share on Portuguese Facebook sites. Frontiers in Psychology. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- César, F. , Oliveira, A. , & Fontaine, A. M. (2020). Mães cuidadoras, pais imperfeitos: diferenças de género numa revista portuguesa para mães e pais [Caring mothers, imperfect fathers: Gender differences in a Portuguese magazine for mothers and fathers]. Ex aequo, 41, 179–194. 10.22355/exaequo.2020.41.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver, L. , Lachman, J. M. , Sherr, L. , Wessels, I. , Krug, E. , Rakotomalala, S. , Blight, S. , Hillis, S. , Bachman, G. , Green, O. , Butchart, A. , Tomlinson, M. , Ward, C. L. , Doubt, J. , & McDonald, K. (2020). Parenting in a time of Covid‐19. Lancet, 395(10231), e64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conselho Nacional de educação [Portuguese Education Council] . (2019). Estado da Educação 2018 [State of education 2018]. https://www.cnedu.pt/pt/noticias/cne/1496‐estado‐da‐educacao‐2018

- Coyne, L. W. , Gould, E. R. , Grimaldi, M. , Wilson, K. G. , Baffuto, G. , & Biglan, A. (2020). First things first: Parent psychological flexibility and self‐compassion during COVID‐19. Behavior analysis in practice. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s40617-020-00435-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, L. , & Churchill, B. (2020). Dual‐earner parent couples' work and care during COVID‐19. Gender, Work and Organization, 28(Suppl. 1), 66–79. 10.1111/gwao.12497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, L. , Rapa, E. , & Stein, A. (2020). Protecting the psychological health of children through effective communication about COVID‐19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 4(5), 346–347. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30097‐3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diário da República Eletrónico . (2020a). Decreto‐Lei n° 10‐A/2020. Estabelece medidas excecionais e temporárias relativas à situação epidemiológica do novo Coronavírus—COVID 19 [Exceptional and temporary measures in response to the COVID‐19 epidemiological situation]. https://dre.pt/web/guest/pesquisa/‐/search/130243053/details/normal?l=1

- Diário da República Eletrónico . (2020b). Presidential Decree n° 20‐A/2020. Procede à segunda renovação da declaração de estado de emergência, com fundamento na verificação de uma situação de calamidade pública [Proceeding with the second renewal of the declaration of the state of emergency, based on public calamity]. https://data.dre.pt/eli/decpresrep/20‐A/2020/04/17/p/dre

- Dias, S. , Pedro, A. R. , Abrantes, A. , Gama, A. , Moniz A. M., Nunes, C. , Parreira, C. , Avelar, F. , Soares, P. , Laires, P. , & Santana, R. (2020). Opinião Social: Perceção individual do risco de contrair COVID‐19, Barómetro COVID‐19 [Social opinion: perception of risk concerning COVID‐19, COVID‐19 Barometer]. Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública da Universidade Nova de Lisboa. [Google Scholar]

- Direção Geral de Saúde [Directorate‐General for Health] . 2020. Current situation in Portugal ‐ report. https://covid19.min‐saude.pt/ponto‐de‐situacao‐atual‐em‐portugal/

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, A. K. (2020). Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s10896-020-00172-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística . (2014). Famílias em Portugal. https://www.animar‐dl.pt/documentacao/pdf/102‐geral/409‐familias‐em‐portugal

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (2019). Inquérito à utilização de tecnologias de informação e da comunicação nas famílias [Survey on the use of information and communication technologies in households]. https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/438632477.

- Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, M. (2019). Gênero e papéis de gênero no fenómeno da conciliação trabalho‐família: Revisões conceituais e estudos empíricos [Gender and gender roles in the phenomenon of work‐family reconciliation: Conceptual reviews and empirical studies]. In Andrade C., Coimbra S., Matias M., Faria L., Gato J., & Antunes C. (Org.), Olhares sobre a Psicologia Diferencial [Differential Psychology] (pp. 174–204). Mais Leitura. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, M. , Aguiar, J. , César, F. , Braz, A. C. , Barham, E. J. , Leme, V. , Elias, L. , Gaspar, M. F. , Mikolajczak, M. , Roskam, I. , & Fontaine, A. M. (2020). The Brazilian‐Portuguese version of the Parental Burnout Assessment: Transcultural adaptation and initial validity evidence. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 174, 67–83. 10.1002/cad.20374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias, M. , Andrade, C. , & Fontaine, A. M. (2012). The interplay of gender, work and family in Portuguese families. Work Organisation, Labour & Globalisation, 6, 11–26. 10.13169/workorgalaboglob.6.1.0011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matias, M. , & Fontaine, A. M. (2015). Coping with work and family: How do dual‐earners interact? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(2), 212–222. 10.1111/sjop.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, H. J. , Wong, K. R. , Nguyen, K. N. , Mahamadachchi, K. N. D. (2020). Covid‐19 and women's triple burden: Vignettes from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam and Australia. Social Sciences, 9(5), 87. 10.3390/socsci9050087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczak, M. , Brianda, M. E. , Avalosse, H. , & Roskam, I. (2018). Consequences of parental burnout: a preliminary investigation of escape and suicidal ideations, sleep disorders, addictions, marital conflicts, child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect, 80, 134–145. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczak, M. , Gross, J. J. , & Roskam, I. (2019). Parental burnout: What is it, and why does it matter? Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1319–1329. 10.1177/2167702619858430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczak, M. , & Roskam, I. (2018). A theoretical and clinical framework for parental burnout: The balance between risks and resources. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 886. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, S. H. (2014). Women's vulnerabilities due to the impact of climate change: Case from Satkhira region of Bangladesh. Global Journal of Human Social Science, 14, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Perista, H. , Cardoso, A. , Brázia, A. , Abrantes, M. , Perista, P. , & Quintal, E. (2016). The use of time by men and women in Portugal: Policy brief. CESIS—Centro de Estudos para a Intervenção Social; CITE—Comissão para a Igualdade no Trabalho e no Emprego. http://cite.gov.pt/asstscite/downloads/publics/INUT_livro_digital.pdf [Google Scholar]

- PORDATA/INE . (2020). Dimensão média dos agregados domésticos privados. [Average size of private households] Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos. https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Dimens%c3%a3o+m%c3%a9dia+dos+agregados+dom%c3%a9sticos+privados+‐511 [Google Scholar]

- Portugal, S. (2011). Dádiva, família e redes sociais [Gift, family and social networks]. In Portugal S. & Martins P. H. (Eds.), Cidadania, políticas públicas e redes sociais (pp. 39–54). Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. 10.14195/978-989-26-0222-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prioste, A. , Narciso, I. , Gonçalves, M. M. , & Pereira, C. R. (2017) Values' family flow: associations between grandparents, parents and adolescent children. Journal of Family Studies, 23(1), 98–117. 10.1080/13229400.2016.1187659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prikhidko, A. , & Swang, J. M. (2020). Exhausted parents experience of anger: The relationship between anger and burnout. The Family Journal, 28(3), 283–289. 10.1177/1066480720933543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, N. (2012). Avós e netos através da(s) imagem(s) e das culturas [Grandparents and grandchildren seen through images and across cultures]. In Ramos N., Marujo M., & Baptista A. (Eds.), A voz dos avós: Migração, memória e património cultural (pp. 33–57). Gráfica de Coimbra, Publicações Lda., Fundação ProDignitate. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, K. M. , Schiffrin, H. H. & Liss, M. (2013). Insight into the parenthood paradox: Mental health outcomes of intensive mothering. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22, 614–620. 10.1007/s10826-012-9615-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Röhr, S. , Müller, F. , Jung, F. , Apfelbacher, C. , Seidler, A. , & Riedel‐Helle, S. G. (2020). Psychosocial impact of quarantine measures during serious coronavirus outbreaks: a rapid review. Psychiatrische Praxis, 47(4), 179–189. 10.1055/a-1159-5562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskam, I. , Brianda, M. E. , & Mikolajczak, M. (2018). A step forward in the conceptualization and measurement of parental burnout: The Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 758. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskam, I. , & Mikolajczak, M. (2020). Gender differences in the nature, the antecedents, and the consequences of parental burnout. Sex Roles, 83, 485–498. 10.1007/s11199-020-01121-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkkila, M. , & Aunola, K. (2020). Risk factors for parental burnout among Finnish parents: The role of socially prescribed perfectionism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 648–659. 10.1007/s10826-019-01607-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B. , & Fidell, L. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, N. , Veríssimo, M. , Monteiro, L. , Ribeiro, O. , & Santos, A. J. (2014). Domains of father involvement, social competence and problem behavior in preschool children, Journal of Family Studies, 20(3), 188–203. 10.1080/13229400.2014.11082006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Women . (2020, November 25). Whose time to care? Unpaid care and domestic work during COVID‐19. https://data.unwomen.org/publications/whose‐time‐care‐unpaid‐care‐and‐domestic‐work‐during‐covid‐19

- Usher, K. , Bhullar, N. , Durkin, J. , Gyamfi, N. , & Jackson, D. (2020). Family violence and COVID‐19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support . International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. Advance online publication. 10.1111/inm.12735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vinkers, C. H. , van Amelsvoort, T. , Bisson, J. I. , Branchi, I. , Cryan, J. F. , Domschke, K. , Howes, O. D. , Manchia, M. , Pinto, L. , de Quervain, D. , Schmidt, M. V. , & van der Wee, N. (2020). Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 35, 12–16. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall, K . (2002). Modos de guarda das crianças nas famílias portuguesas [Child custody modes in Portuguese families]. In Atas do IV Congresso Português de Sociologia: Sociedade Portuguesa: Passados Recentes, Futuros Próximos . https://aps.pt/wp‐content/uploads/2017/08/DPR462e00f42e652_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wall, K. , Cunha, V. , Atalaia, S. , Rodrigues, L. , Correia, S. V. , & Rosa, R. (2016). Editorial do Ministério da Educação e Ciência [White paper: Men and gender equality in Portugal]. http://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/26649/1/ICs_KWall_LivroBranco_Outros.pdf

- Wall, K. , & Leitão, M. (2017). Fathers on leave alone in Portugal: Lived experiences and impact of forerunner fathers. In O'Brien Margaret & Wall Karin (Eds.), Comparative perspectives on work–life balance and gender equality (pp. 45–67). Springer Open. 10.1007/978-3-319-42970-0_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020, March 18). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID‐19 outbreak. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331490