Abstract

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, an unprecedented number of employees faced the challenges of telework. However, the current literature has a limited understanding of the implications of employees' obligated home‐based telework and their satisfaction with the work and home domains. We use boundary theory to examine work and home boundary violations in relation to satisfaction with domain investment in two daily diary studies, examining both domain‐specific and cross‐domain effects. In addition, we examine the moderating role of segmentation preferences in both studies and investigate the mediating role of work‐ and home‐related unfinished tasks in Study 2. Both studies provide empirical evidence of the domain‐specific relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction and provide limited support for cross‐domain effects. Neither study finds support for the notion that segmentation preferences moderate the relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction. Finally, the results of Study 2 highlight the importance of unfinished tasks in the relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction. Specifically, work and home boundary violations relate to an increase in unfinished tasks in both domains. Finally, the indirect effects suggest that home‐related unfinished tasks may be detrimental to satisfaction in both domains, while work‐related unfinished tasks may be detrimental for work‐related, but not home‐related, satisfaction.

Keywords: boundary violations, domain satisfaction, segmentation preferences, telework, unfinished tasks

INTRODUCTION

It's hard to separate work demands and home demands, especially with kids. At the end of the day, I realized I did not focus enough on work but also wasn't fully present in my private life. Study participant, April 2020

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a world pandemic due to the spread of the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus (World Health Organization, 2020), leading to major changes in the everyday lives of employees. In the EU, an unprecedented 40% of the working population began telework due to the pandemic (Milasi et al., 2020) and was required to adapt to work from home. This measure reduced exposure to the virus and its spread (Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 2020), affording some continuance to organizations (Eurofound, 2020). However, employees may not have been well prepared for the unique challenges of home‐based telework, considering that only 15% of employees in the EU had any experience with telework prior to the pandemic. Furthermore, the closure of childcare and educational institutions provided additional challenges to the work–life balance, especially for women (Rudolph et al., 2020; Shockley et al., 2020). Reports early in the pandemic found that employees struggled to balance their work and private life (Eurofound, 2020; Vaziri et al., 2020). Both the above quotation from a study participant and published reports demonstrate that employees may struggle with their work–life boundary, leaving them dissatisfied with both domains.

Boundary violations occur when certain events or behaviors breach or neglect the boundary between work and private life (Kreiner et al., 2009). For example, receiving a work‐related phone call outside of work hours violates the home boundary, while receiving a private phone call during work hours violates the work boundary. Such boundary violations have been shown to lead to dissatisfaction with investment in work or home domains in previous literature (Hunter et al., 2019). Moreover, in light of the pandemic, work and private life are likely to be highly intertwined as a result of the required home‐based telework, blurring the boundary between the domains (Allen et al., 2020; International Labour Organization, 2020) and creating more opportunities for boundary violations. Thus, the first contribution of the present research is the examination of the relationship between daily work and home boundary violations and satisfaction with investment in work and home domains. Furthermore, we go beyond domain‐specific effects (how boundary violations in one domain relate to satisfaction in the same domain) to examine cross‐domain effects as well (how boundary violations in one domain relate to satisfaction in the other domain), which has been neglected in the previous literature but may be especially relevant in the context of home‐based telework.

Second, we contribute to the literature by examining the role of segmentation preferences, that is, the degree, to which employee prefers to keep work‐ and private‐life separate (Ashforth et al., 2000; Kreiner et al., 2009). Segmentation preferences may play a relevant role in the relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction, 1 as it results in strategies to manage the work–home boundary (Derks et al., 2016). Literature finds that segmentors may perceive boundary violations as more stressful than integrators or have a harder time tackling them (Delanoeije et al., 2019; Derks et al., 2016). Furthermore, it is necessary to consider the possibility of enacting the preferred strategy (Allen et al., 2014; Ashforth et al., 2000), especially in the context of required home‐based telework (Allen et al., 2020). Put differently, the current situation of required home‐based telework removes the self‐selection effect (i.e. segmentors may be less likely to choose telework; Allen et al., 2020) and offers a unique opportunity to examine the role of segmentation preferences as a moderator of the relationship between daily boundary violations and domain satisfaction.

Third, the present research contributes to the literature by investigating the role of unfinished tasks as an additional pathway linking boundary violations and domain satisfaction. Previous literature has linked boundary violations to domain satisfaction via goal obstruction (Hunter et al., 2019). However, what happens at the actual task level remains unexamined but may be especially relevant when employees face increased overlap and interruptions between work and home domains. Furthermore, although unfinished tasks have been linked to employee outcomes, such as affective rumination and well‐being (Peifer et al., 2019; Syrek et al., 2017), the literature examining unfinished tasks is still scarce, both generally and in the context of telework. Thus, we investigate the mediating role of unfinished tasks, focusing on both work‐related and home‐related unfinished tasks, and examine both the domain‐specific and cross‐domain effects.

The final contribution of the present research comes from the utilization of a daily diary design. Previous literature on telework mainly relies on cross‐sectional design (Allen et al., 2015; Delanoeije & Verbruggen, 2020), comparison of telework users with non‐users (Delanoeije & Verbruggen, 2020), or comparison between teleworking days and non‐teleworking days (Delanoeije et al., 2019). Furthermore, previous research shows that work–life boundaries (Hunter et al., 2019; Spieler et al., 2017), unfinished tasks (Peifer et al., 2019), and even job satisfaction (Hülsheger et al., 2013) tend to fluctuate daily. Thus, a daily diary design is best suited to capture the daily variability and provide additional insight into the mechanisms behind satisfaction with work and home domains. Understanding such processes is especially relevant, considering that the increased use and availability of telework is likely to continue in the future.

To summarize, the present research examines boundary violations and their relationship to work‐ and home‐domain satisfaction in two diary studies. In Study 1, we examine the domain‐specific and cross‐domain effects and further investigate the moderating role of segmentation preferences. In Study 2, we attempt to replicate Study 1 findings and further investigate the mediating role of unfinished tasks. Thus, our research examines the work–life boundary experiences of employees during home‐based telework due to the pandemic. Furthermore, as the pandemic has compelled many organizations to establish the infrastructure for telework, providing the means for telework to continue after the pandemic, such an examination may inform the literature and practitioners on potential pitfalls of home‐based telework.

STUDY 1: DOMAIN‐SPECIFIC AND CROSS‐DOMAIN RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN BOUNDARY VIOLATIONS AND SATISFACTION WITH INVESTMENT

In general, the concept of boundaries refers to the physical, temporal, emotional, cognitive, and relational limits that separate one entity from another. Thus, employees create and maintain physical, behavioral, and psychological boundaries that differentiate the work and the home domain (Ashforth et al., 2000). Previous research shows that home‐based telework tends to blur the boundary between work and private life, allowing for more interruptions or violations from one domain to another (Delanoeije et al., 2019). According to Kreiner et al. (2009), boundary violations can be described as intrusions, occurring when an employee desires segmentation but a violation forces integration or when an employee is unable to prevent the spillover from one domain to another. Previous research shows a link between boundary violations and domain satisfaction. Specifically, a daily diary study by Hunter et al. (2019) examined the relevance of daily boundary violations for work–life outcomes such as satisfaction with investment in the domain. The study partially supported the direct relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction and negative affect via goal obstruction.

Boundary violations can also be described as interruptions (Ashforth et al., 2000; Hunter et al., 2019), which are usually unexpected and uncontrollable (Keller et al., 2020). The literature on work‐related interruptions also provides support for the relationship between interruptions and task‐ or work‐related satisfaction. Specifically, regardless of whether the individual accepts or rejects the new, interrupting task or demands, the interruption will break task continuity and workflow (Brixey et al., 2007; Peifer et al., 2019), potentially causing frustration and dissatisfaction with owns' performance (Baethge et al., 2015; Baethge & Rigotti, 2013). In other words, when an employee frequently experiences work‐boundary violations by, for example, interruptions or requests from a family member during work hours, such violations hinder the employees' involvement with the task at hand, generating negative affect and dissatisfaction with their investment in the work domain. A similar relationship can be proposed for the home domain; when an employee is, for example, engaged in play with their child and the playtime is interrupted by unexpected work communications which direct the employees' attention away from the child, such interruptions may leave the employee dissatisfied with their investment in the home domain. Although the study by Hunter et al. (2019) found limited support for the relationship between boundary violations and satisfaction with investment in the domain, we argue that it is necessary to examine such a relationship in the context of required home‐based telework, as the boundary between work and private life may become increasingly blurred.

Furthermore, we argue that beyond the domain‐specific effects, cross‐domain effects should also be examined. Boundary violations (i.e. interruptions) not only hinder the task at hand but direct the individual's attention to a new, interrupting task or demand. The research on interruptions finds that when individuals must switch to the new (interrupting) task, their performance and satisfaction with the new task suffer because it is difficult for individuals to entirely cognitively abandon the primary task and fully focus on the new task (Leroy, 2009). Furthermore, even rejecting or postponing the interrupting task can potentially relate to dissatisfaction in the other (interrupting) domain, as the interruption itself is indicative of an unexpected or unplanned demand arising, thus increasing the number of tasks the individual has to tackle (Baethge & Rigotti, 2013; Keller et al., 2020). A similar result can be expected from boundary violations. When an employee is interrupted during a work task by a family member with a request, such interruption will not only generate dissatisfaction with the work domain (domain‐specific effect) but also may lead to dissatisfaction with the home domain (cross‐domain effect), as the employee either has to postpone or reject the interrupting demand or is unable to give the interrupting task their full attention. Taken together, we expect negative domain‐specific and cross‐domain effects of boundary violations on satisfaction with investment in the domain.

Hypothesis 1

Daily work boundary violations will negatively predict work‐related (H1a) and home‐related (H1b) satisfaction with investment on the same day.

Hypothesis 2

Daily home boundary violations will negatively predict home‐related (H2a) and work‐related (H2b) satisfaction with investment on the same day.

The role of segmentation preferences

Segmentation preferences describe how an employee constructs, dismantles, and maintains the work–home boundary. Individuals vary in their preferences on a continuum from segmentation, where a rigorous boundary between work and private life with little cross‐boundary interruptions is preferred, to integration, where the preferred boundary is permeable and flexible, welcoming cross‐boundary interruptions (Ashforth et al., 2000; Kreiner et al., 2009). Thus, “integrators” may permit more boundary‐blurring and violations and find it easier to tackle them. “Segmentors” may allow less boundary‐blurring and violations and may have a harder time tackling them when they occur (Allen et al., 2014; Kreiner et al., 2009). Previous research shows that integrators tend to create fewer boundaries between work and life and have less negative reactions to boundary violations and interruptions (Olson‐Buchanan & Boswell, 2006), while segmentors tend to create more boundaries, which is in turn associated with fewer interruptions and interference (Park & Jex, 2011). Furthermore, segmentors are thought to use the primary strategy of creating temporal and spatial boundaries to keep the domains separate (Ashforth et al., 2000).

Employees engaged in required home‐based telework may find that strategies to keep work and private life separate are less available or effective as the work and home domains become increasingly blended. In other words, individuals who prefer segmentation may be less able to manage and react to boundary violations. Thus, we propose that segmentation preferences act as a moderator of the relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3

Segmentation preferences will moderate the relationship between work boundary violations and work‐related satisfaction (H3a) as well as home‐related satisfaction (H3b), such that the relationship will be more negative for individuals who prefer segmentation.

Hypothesis 4

Segmentation preferences will moderate the relationship between home boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction (H4a) and work‐related satisfaction (H4b), such that the relationship will be more negative for individuals who prefer segmentation.

METHOD

Sample and procedure

Between March and May of 2020, employees working from home were invited to partake in the study, using the author's formal and informal networks. A daily diary design was utilized to examine daily variability in boundary violations and their relationship to daily domain satisfaction. Because home‐based telework increases temporal flexibility (Kossek et al., 2006), boundary violations may occur at any time of the day. Thus, participants were asked to fill out a single survey before going to bed for five workdays (Monday to Friday).

One hundred twenty‐eight employees completed at least three out of five diaries (M = 4.2), resulting in 541 observations. More than half of the sample were female participants (58.2%), and the average age was 36.8 years (standard deviation, SD = 9.8). Our sample was highly educated; 44.8% had a master's degree, followed by 25.4% with a doctorate. More than half of the sample (72.4%) resided in Slovenia, 10.4% resided in Austria, and 0.7% resided in Netherlands or Germany. Most participants (71.5%) had permanent employment; 29.9% of participants worked in education, 17.2% worked in research, followed by 9% of participants who held managerial jobs, 9% who worked in finance, and 8.2% were social professionals. Regarding tenure at the current position, 29.6% of the sample had 1–5 years, followed by 26.1% who had over 10 years. Leadership positions were held by 17.9% of participants. On average, employees worked 39.6 h/week (SD = 13.3). Most participants were married or in a relationship (73.9%), and 38.8% had children. For 7.1% of the parents, the youngest child was 3–5 years of age, followed by 6.9% whose children were 18 or more. Regarding childcare, 12.7% of parents stated that they do not require help with childcare. Of the parents that did require help with childcare, 28.6% stated that they almost never had help available, 2.9% rarely had help available, 28.6% occasionally had help available, 11.4% often had help available, and 28.6% had help available almost always.

Measures

General measures

The Segmentation Preferences Scale, developed by Kreiner (2006), was used to assess the segmentation preferences of employees. The scale comprises four items (sample item: “I don't like work issues creeping into my home life”), measured on a 5‐point scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The items showed adequate reliability (α = .90).

Daily measures

The three items addressing the work boundary from the Boundary Violations Scale (Hunter et al., 2019) were used to measure private life violating the work boundary (work boundary violations; sample item: “Today, in my work, my private life has interrupted my work more than I desire.”). The items were assessed on a 5‐point scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, and showed adequate reliability (α = .72).

The three items, relating to private life boundary from the Boundary Violations Scale (Hunter et al., 2019), were used to measure work violating the private life boundary (home boundary violations; sample item: “Today, in my private life, my work has interrupted my private life more than I desire.”). The items were assessed on a 5‐point scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, and showed adequate reliability (α = .65).

The three work‐related items from the Satisfaction With Investment in Work/Family Scale (Hunter et al., 2019) were used to measure satisfaction with investment in the work domain (sample item: “Today, I feel satisfied with the amount of time I devoted to my job.”). The items were assessed on a 5‐point scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, and showed adequate reliability (α = .83).

The three items related to private life from the Satisfaction With Investment in Work/Family (Hunter et al., 2019) were used to measure satisfaction with investment in the home domain (sample item: “Today, I feel satisfied with the amount of time I devoted to my private life”). The items were assessed on a 5‐point scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, and showed adequate reliability (α = .93).

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics, interclass correlations (ICCs), and correlations between study variables can be found in Table 1. Because observations were nested within individuals, our data called for a multilevel approach to analysis. First, we examined the within‐ and between‐person level variance using ICCs (see Table 1), which confirmed that a multilevel approach was justified. To investigate domain‐specific and cross‐domain effects of boundary violations on domain satisfaction (Model 1), we included all variables in a single model. In addition, correlation terms between work and home boundary violations and between work‐ and home‐domain satisfaction were included, resulting in a saturated model. Finally, to examine the moderating role of segmentation preferences, four cross‐level interaction terms were tested for significance. Following recommendations (Hofmann et al., 2000), we centered boundary violations at person mean and segmentation preferences at the grand mean. Analyses were carried out using Mplus 8 (Muthen & Muthen, 2017).

TABLE 1.

Means, standard deviations, interclass correlations and zero‐order correlations among study 1 and 2 variables

| M | SD | ICC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | ||||||||||

| 1. Work boundary violations | 2.35 | 0.98 | 0.62 | .66 *** | −.68 *** | −.44 *** | −.02 | |||

| 2. Home boundary violations | 2.31 | 0.94 | 0.60 | .33 *** | −.49 *** | −.61 *** | −.05 | |||

| 3. Satisfaction with work | 3.57 | 0.92 | 0.45 | −.21 *** | −.02 | .44 *** | −.06 | |||

| 4. Satisfaction with private life | 3.46 | 1.02 | 0.45 | −.18 *** | −.26 *** | .17 ** | −.03 | |||

| 5. Segmentation preferences | 3.38 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Study 2 | ||||||||||

| 1. Work boundary violations | 2.31 | 1.04 | 0.47 | .77 *** | −.62 *** | −.50 *** | .19 * | .58 *** | .61 *** | |

| 2. Home boundary violations | 2.25 | 0.97 | 0.49 | .44 *** | −.49 *** | −.66 *** | .28 *** | .58 *** | .69 ** | |

| 3. Satisfaction with work | 3.66 | 0.97 | 0.39 | −.42 *** | −.09 | .33 * | −.17 | −.73 *** | −.22 | |

| 4. Satisfaction with private life | 3.65 | 0.89 | 0.41 | −.11 | −.27 *** | .08 | −.23 ** | −.39 *** | −.65 *** | |

| 5. Segmentation preferences | 4.01 | 0.96 | ||||||||

| 6. Work‐related unfinished tasks | 2.34 | 1.01 | 0.46 | .44 *** | .29 *** | −.52 *** | −.12 * | .46 *** | ||

| 7. Home‐related unfinished tasks | 2.34 | 1.02 | 0.45 | .24 *** | .29 *** | −.19 ** | −.43 *** | .14 ** | ||

Note. Within‐level correlations are displayed below the diagonal, and between‐level correlations are displayed above the diagonal.

Abbreviations: ICC, interclass correlation; SD, standard deviation.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Our results, displayed in Table 2, showed that work boundary violations negatively and significantly predicted work‐related satisfaction, supporting Hypothesis 1a. Work boundary violations also negatively and significantly predicted home‐related satisfaction, supporting Hypothesis 1b. Regarding the home domain, our results support Hypothesis 2a, which states that home boundary violations negatively predict home‐related satisfaction. However, we were unable to support Hypothesis 2b, as home boundary violations did not significantly predict work‐related satisfaction.

TABLE 2.

Study 1 and 2 within‐level estimates of model 1

| Est. | S.E. | Est./S.E. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | |||

| Work boundary violations → work‐related satisfaction | −0.23 | 0.06 | −3.98 *** |

| Work boundary violations → home‐related satisfaction | −0.10 | 0.05 | −2.11 * |

| Home boundary violations → home‐related satisfaction | −0.23 | 0.05 | −4.22 *** |

| Home boundary violations → work‐related satisfaction | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.02 |

| Home boundary violations ↔ work‐boundary violations | 0.33 | 0.06 | 5.94 *** |

| Home related satisfaction ↔ work‐related satisfaction | 0.16 | 0.07 | 2.29 |

| Study 2 | |||

| Work boundary violations → work‐related satisfaction | −0.47 | 0.06 | −8.13 *** |

| Work boundary violations → home‐related satisfaction | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| Home boundary violations → home‐related satisfaction | −0.28 | 0.06 | −4.04 *** |

| Home boundary violations → work‐related satisfaction | 0.11 | 0.09 | 1.19 |

| Home boundary violations ↔ work‐boundary violations | 0.44 | 0.05 | 8.86 *** |

| Home‐related satisfaction ↔ work‐related satisfaction | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.16 |

Note. The table displays standardized estimates and unstandardized p‐values. A single‐headed arrow indicates a regression term, a double‐headed arrow indicates a correlation term.

p ≤ .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We then examined the moderating role of segmentation preferences. The results show that segmentation preferences did not moderate the relationship between work boundary violations and work‐related (H3a; γ = −.05; t = −.76; p = .45) or home‐related satisfaction (H3b; γ = .05; t = .81; p = .42). Furthermore, segmentation preferences did not moderate the relationship between home boundary violations and home‐related (H4a; γ = .07; t = .97; p = .33) or work‐related satisfaction (H4b; γ = < −.01; t = −.02; p = .98). Thus, our results do not support Hypotheses 3 and 4.

Additional analyses

To gain additional insight regarding boundary violations in times of the COVID‐19 pandemic, we examined whether gender and having children may play a role in the relationship between daily boundary violations and domain satisfaction (Model 1). Specifically, we tested Model 1 across four groups (Men with children, Men without children, Women with children, and Women without children) using a two‐level mixture model with known groups (Muthen & Muthen, 2017). The results did not differ from Model 1 results (in terms of valence and significance of the effects) for groups Men without children and Women with children. The results showed a nonsignificant relationship between daily work boundary violations and work satisfaction for Men with children, although this may be due to small group size (N = 15; Cohen, 2013). Finally, the results showed a significant negative cross‐domain relationship between daily work boundary violations and home satisfaction for the group Women without children. Taken together, the results for the groups Men with children and Women without children deviate from Model 1 results of the entire sample. Detailed results can be found in online supplements.

STUDY 2: REPLICATION OF STUDY 1 FINDINGS

In Study 2, we first attempt to replicate the Study 1 findings, which provided support for domain‐specific effects of boundary violations on domain satisfaction (Hypotheses 1a and 2a), and the cross‐domain effect of work‐boundary violations on home‐related satisfaction (Hypothesis 1b). Study 1 results did not support the cross‐domain effect of home boundary violations on work‐related satisfaction (Hypothesis 2b). We also examine Hypotheses 3 and 4 regarding the moderating role of segmentation preferences, which Study 1 results did not support, and examine the role of gender and having children. Furthermore, as the sample in Study 1 was highly educated and employed mainly in higher education and research, we attempt to replicate the Study 1 findings in a more heterogeneous sample of employees.

Work‐related and home‐related unfinished tasks as an additional pathway

Boundary violations are often described as interruptions, as one's role engagement, activity, or task in one domain is interrupted by a demand from the other domain (Hunter et al., 2019; Kreiner et al., 2009). Previous literature indicates that boundary violations may be related to unfinished tasks. Specifically, a daily diary study by Hunter et al. (2019) found that boundary violations obstructed goals in the same domain; however, further mediation via negative affect to domain satisfaction was not supported. We argue that it is necessary not only to examine the relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction in the context of telework but to go beyond goal obstruction and examine this process on a task level (i.e. unfinished tasks).

Specifically, goal obstruction does not necessarily indicate incompletion of the task at hand. However, as the literature indicates, unfinished tasks may be a great source of dissatisfaction to individuals. In a series of experiments, Zeigarnik (1938) found that when tasks were left unfinished due to an interruption, individuals experienced dissatisfaction and frustration, and furthermore, the task remained cognitively active after switching to a new task (known as the Zeigarnik effect; Zeigarnik, 1938). In the work context, Syrek et al. (2017) described unfinished tasks as “tasks that the employee aimed to finish (or make certain progress), but which were left undone (or left in an unsatisfactory state) when the employee stopped working” (p. 227). Further attesting to the link between boundary violations and unfinished tasks is the notion that personal resources (e.g. time, energy) spent in one domain become unavailable in the other domain (Hobfoll, 1989); hence, tackling interruptions may diminish employees' resources in that domain and increase the occurrence of unfinished tasks. Thus, we argue that it is necessary to examine the role of both work‐ and home‐related unfinished tasks in the relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction, as boundary violations may result in unfinished tasks, which can in turn decrease domain satisfaction.

In addition to domain‐specific effects (i.e. interruptions to the work boundary relate to work‐related unfinished tasks), we argue that although largely unexamined, cross‐domain effects may be expected as well. In other words, we propose that boundary violations (i.e. interruptions) relate to unfinished tasks in the other (interrupting) domain as well. First, as interruptions are often unexpected and unplanned (Baethge & Rigotti, 2013; Puranik et al., 2020) and indicative of new demands emerging from the other domain (Hunter et al., 2019), employees faced with frequent interruptions from work or home domain are likely facing an increased amount of demands in that domain (e.g. if a child needs unexpected help with a school project, this will create new demand in the home domain of the employee). As the employee faces an increased amount of demands, this may result in unfinished tasks (Baethge et al., 2015). In addition to facing an increase in demands from the interrupting domain, employees may not be able to tackle the interrupting demand due to engagement in the other domain. In other words, the employee may not be able to help their child with the school project when the help is requested because the employee is tackling work‐related tasks. Taken together, when an employee is interrupted by a request or demand from the home domain while engaged in a work task, this interruption may not only disrupt the work task at hand but may also leave an unfinished task in the home domain if the employee is unable to tackle it.

Based on previous literature, a link between unfinished tasks and domain satisfaction can also be argued. The experiments performed by Zeigarnik (1938) found that individuals experienced dissatisfaction and frustration when tasks were left unfinished. Similarly, Peifer et al. (2019) found that unfinished tasks relate to negative affect, such as dissatisfaction, suggesting that domain‐specific unfinished tasks may negatively relate to domain satisfaction. In addition, the literature provides an argument for cross‐domain effects. Specifically, research finds that unfinished tasks remain cognitively active even after switching to the new task (Zeigarnik, 1938) and may result in rumination (Syrek et al., 2017; Syrek & Antoni, 2014), making it difficult to give full attention to the task at hand. Thus, an unfinished task in one domain may diminish engagement (or its quality) in the other domain, reducing the satisfaction in that domain. For example, an employee may be mentally occupied with unfinished work tasks when spending time with a family member, unable to give them full attention, which may leave them dissatisfied with their investment in the home domain. Taken together, we propose that work‐ and home‐related unfinished tasks mediate the relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction.

Hypothesis 5

The relationship between work boundary violations and work‐ (H5a) or home‐related satisfaction with investment (H5b) is mediated by work‐related unfinished tasks.

Hypothesis 6

The relationship between work boundary violations and work‐ (H6a) or home‐related satisfaction with investment (H6b) is mediated by home‐related unfinished tasks.

Hypothesis 7

The relationship between home boundary violations and home‐ (H7a) or work‐related satisfaction with investment (H7b) is mediated by home‐related unfinished tasks.

Hypothesis 8

The relationship between home boundary violations and home‐ (H8a) or work‐related satisfaction with investment (H8b) is mediated by work‐related unfinished tasks.

METHOD

Sample and procedure

UK employees working from home due to the pandemic were recruited in August 2020 through Prolific, which is an online survey platform. One hundred thirty‐eight employees participated for at least three out of five workdays (Monday to Friday, M = 4.4), resulting in 601 observations. More than half of the sample were female participants (55.6%), and the average age was 36.2 years (SD = 10.12). Bachelor's degrees were held by 48.3% of participants, followed by participants with a master's degree (26.1%). The majority of the sample (78.5%) was employed full‐time and had an average position tenure of 2.43 years (SD = 0.93). Participants worked 37.7 h/week on average (SD = 6.5). Regarding the sector of employment, 13.5% of the participants worked in education; 13.5% worked in accounting, banking, and finance; 10.7% worked in public services and administration; 8.5% worked in information technology; 5.7% worked in retail and sales; and 5% worked in engineering and manufacturing. Leadership positions were held by 37.9% of participants. The majority of the sample was married or in a relationship (62.3%), and 36.6% had children; 7.6% of children were 6–8 years old, 7.6% were age 18 or older, and 7.3% were between 1 and 3 years old. Regarding childcare, a small portion of parents (2.1%) stated that they do not require any help with childcare. Of the parents that did require help with childcare, 22.4% almost never had help available, 6.1% had help available rarely, 18.4% occasionally had help available, 26.5% had help available often, and 26.5% almost always had help available. To attempt to replicate the Study 1 findings, the same study design was applied (see Study 1 Method).

Measures

To attempt to replicate the Study 1 findings, we applied the same scales in Study 2; the Segmentation Preference Scale by Kreiner (2006, α = .92), the Boundary Violations Scale by Hunter et al. (2019, α = .84 and .79 for work and home boundary violations, respectively), and satisfaction with investment in work/family by Hunter et al. (2019, α = .88 and .90 for work and home domain, respectively).

The Unfinished Tasks Scale (Syrek & Antoni, 2014) was used to measure daily work‐related unfinished tasks. The three items (sample item: “I need to carry many of today's work tasks into tomorrow”) were assessed on a 5‐point scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, and showed adequate reliability (α = .77).

To assess daily home‐related unfinished tasks, we adapted the items from the Unfinished Tasks Scale (Syrek & Antoni, 2014) to the private‐life context. The three items (sample item: I need to carry many of today's chores or private obligations into tomorrow.”) were measured on a 5‐point scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, and showed adequate reliability (α = .83).

RESULTS: REPLICATING THE STUDY 1 FINDINGS

Descriptive statistics, ICCs, and correlations between study variables can be found in Table 1. A multilevel mediation model (Model 2) was applied to our data in order to examine Hypotheses 5–8. Correlation terms between work and home boundary violations, work‐ and home‐related unfinished tasks, and work‐ and home‐related satisfaction were included in the model, resulting in a saturated model.

Results in Table 2 show that Study 1 findings (Model 1) were only partially replicated. Specifically, we found a statistically significant negative relationship between work boundary violations and work‐related satisfaction and between home boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction, providing support for Hypotheses 1a and 2a. In accordance with Study 1, results did not support Hypothesis 2b, as the relationship between home boundary violations and work‐related satisfaction was found to be statistically nonsignificant. However, in contrast to Study 1 and Hypothesis 1b, the relationship between work boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction was found to be statistically nonsignificant.

Regarding the moderating role of segmentation preferences, Study 1 findings were replicated. Specifically, segmentation preferences did not significantly moderate the relationship between work boundary violations and work‐related satisfaction (γ = .44, t = 6.82, p = .65), work boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction (γ = .41, t = 7.86, p = .52), home boundary violation and home‐related satisfaction (γ = .36, t = 7.61, p = .99), or home boundary violations and work‐related satisfaction (γ = .45, t = 8.12, p = .10). Thus, the results did not support Hypotheses 3 and 4.

The role of unfinished tasks

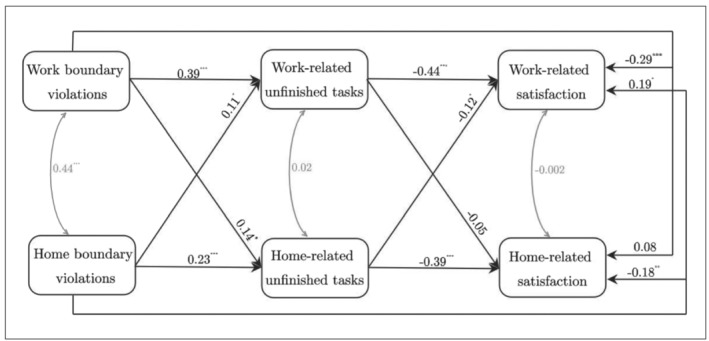

The results of Model 2 are displayed in Figure 1 and show a significant and positive relationship between daily work boundary violations and work‐related unfinished tasks, as well as home‐related unfinished tasks. In a similar manner, a significant positive relationship was observed between daily home boundary violation and home‐related unfinished tasks, as well as work‐related unfinished tasks. Daily work‐related unfinished tasks were negatively and significantly related to work‐related satisfaction but not to home‐related satisfaction. Daily home‐related unfinished tasks were negatively and significantly related to both home‐ and work‐related satisfaction.

FIGURE 1.

Within‐level estimates of the model 2 direct effects. Note. The figure displays standardized estimates and unstandardized p‐values. * p ≤ .05. ** p ≤ .01. *** p ≤ .001

The within‐level indirect effects were estimated in R (R Core Team, 2013), using Monte Carlo confidence intervals (see Preacher & Selig, 2012), results are displayed in Table 3. The Monte Carlo confidence intervals indicate a significant indirect effect for all the effects tested, with the exception of the indirect effects between home boundary violations and home satisfaction via work‐related unfinished tasks, and between work boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction via work‐related unfinished tasks. Thus, the results provide support for Hypotheses 5a, 6, 7, and 8b, but not for Hypotheses 5b and 8a.

TABLE 3.

Monte Carlo estimation of the model 2 indirect effects

| Monte Carlo 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | LL | UL | |

| Work BV → work UT → work satisfaction | −0.17 | −0.23 | −0.11 |

| Work BV → work UT → home satisfaction | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.02 |

| Work BV → home UT → work satisfaction | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.001 |

| Work BV → home UT → home satisfaction | −0.05 | −0.10 | −0.01 |

| Home BV → home UT → home satisfaction | −0.09 | −0.14 | −0.04 |

| Home BV → home UT → work satisfaction | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.01 |

| Home BV → work UT → home satisfaction | −0.004 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Home BV → work UT → work satisfaction | −0.05 | −0.11 | −0.003 |

Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; Home BV, home‐boundary violations; Home satisfaction, home‐related satisfaction with investment; Home UT, home‐related unfinished tasks; Work BV, work‐boundary violations; Work satisfaction, work‐related satisfaction with investment; Work UT, work‐related unfinished tasks.

Additional analyses

In line with Study 1, we additionally investigated the role of gender and having children by examining Model 1 across four groups (Men with children, Men without children, Women with children, and Women without children). The results for groups Men with children, Men without children, and Women with children were comparable to Model 1 results in terms of valence and significance of the effects. However, a negative significant cross‐domain relationship between daily work boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction was observed for group Women without children. In other words, different results can be observed for Women without children in comparison to Model 1 results of the entire sample.

Lastly, we estimated Model 2 based on group membership. Comparing the results for individual groups to the results displayed in Figure 1, several differences were observed. The results for the group Men with children revealed nonsignificant cross‐domain effects between daily boundary violations and unfinished tasks, and a nonsignificant cross‐domain effect between daily home boundary violations and work‐related unfinished tasks was observed for the group Men without children. The results showed a nonsignificant cross‐domain relationship between daily work boundary violations and home‐related unfinished tasks for the group Women with children. In addition, the results revealed significant negative cross‐domain main effects between daily work boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction and between daily home boundary violations and work‐related satisfaction. Finally, the results for group Women without children showed a significant positive relationship between daily home boundary violations and work‐related satisfaction and a nonsignificant relationship between daily home boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction. Thus, slightly different results can be observed for each group. Detailed results of the additional analyses can be found in online supplements.

DISCUSSION

The present research utilized two daily diary studies in the context of required home‐based telework during the COVID‐19 pandemic to examine the relationship of daily work and home boundary violations to daily satisfaction with investment in the work and home domains. Going beyond the domain‐specific effects (e.g. home boundary violations negatively relate to satisfaction with investment in the home domain), we also examined the cross‐domain effects (e.g. work boundary violations negatively relate to satisfaction with investment in the home domain). Furthermore, we examined the moderating role of segmentation preferences in both studies and examined the mediating role of daily work and home‐related unfinished tasks in Study 2. Lastly, additional analyses regarding the role of gender and having children provided further understanding of the relationships examined. Our results offer insight into employee experiences with work–life (home) boundaries and inform the literature on the interplay between work and private life in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Furthermore, considering that telework will likely be available to a greater extent even after the pandemic, our research may inform practitioners and organizations on potential threats to work–life balance and employee satisfaction.

Theoretical implications

Our research provides strong empirical support for the domain‐specific relationship between boundary violations and satisfaction with domain investment (Model 1). In other words, experiencing daily interruptions to the domain relates to (dis)satisfaction with domain investment for both the work and the home domain. Our findings partially align with previous research. Spreitzer et al. (2017) found that the extended use of flexible work arrangements increased goal obstruction and negative affect. Hunter et al. (2019) found that work boundary violations directly relate to diminished satisfaction with investment in the work domain (and via goal obstruction and negative affect). However, the study did not provide support for the same (direct) effect in the home domain (Hunter et al., 2019), which is in contradiction to the findings of both our studies. Thus, it seems feasible that the effect in the home domain may be more relevant in the context of home‐based telework, where work and private life blend easily and less relevant in a traditional working setting, which allows for more separation between the domains. Furthermore, the COVID‐19 pandemic has forcibly collocated work and private life at the home of the employees, regardless of their preference or capacity to work from home. Thus, the context of the studies likely explains the significant link between home boundary violations and satisfaction with investment in the home domain, not found in previous research (i.e. Hunter et al., 2019).

Based on previous literature on interruptions, namely, that switching to the interrupting task leaves individuals dissatisfied with the new task as well (Leroy, 2009), we assumed that individuals would also experience dissatisfaction in the interrupting domain (cross‐domain effects). However, our results do not unequivocally support this notion. In detail, we found a significant link between work boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction in Study 1, which we were unable to replicate in Study 2. The timing of the data collection may explain the different results obtained. Specifically, Study 1 was carried out at the beginning of the lockdown (between March and May of 2020), and Study 2 was carried out in August of 2020. Thus, it is likely that employees were less adapted to the specifics of home‐based telework and less effective in managing the work–life boundary during the Study 1 data collection. According to Work Adjustment Theory (Dawis et al., 1968), changes to work or working situation will likely initiate the process of adjustment in individuals. Furthermore, research in the context of the pandemic finds a positive relationship between telework duration and adjustment to telework (e.g. Carillo et al., 2020). Taken together, our study provides strong empirical evidence of the domain‐specific link between boundary violations and domain satisfaction. The cross‐domain relationship was not unequivocally supported by our findings and may be more dependent on the broader context of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Based on the boundary theory, which proposes that employees who prefer segmentation between work and private life may find boundary violations more stressful than employees who prefer integration (Hunter et al., 2019; Kreiner, 2006), we examined the moderating role of segmentation preferences. In addition, previous research finds that the ability to use telework in accordance with one's preferences (volition) relates to work–home conflict (Delanoeije & Verbruggen, 2019), which may be especially relevant in the context of obligated telework due to the pandemic. Furthermore, a recent study by Allen et al. (2020) found a positive link between segmentation preferences and work‐related balance during the COVID‐19 pandemic, indicating that segmentors may be more efficient in managing the work–life boundary in the context of required home‐based telework. Unexpectedly, the findings of our study do not support the notion that segmentation preferences play a role in the relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction in terms of required home‐based telework. Because our study focused on satisfaction with domain investment rather than work–life balance, it may be feasible that in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic, the role of segmentation preferences may be relevant for some work–life outcomes but not others. Put differently, it may be that segmentation preferences relate to the employees' perception of work–life balance but do not relate to how employees react to boundary violations or their satisfaction with domain investment. However, our results are accordant with a study by Lapierre et al. (2016), examining work–family conflict in the context of obligated telework. The authors concluded that the preferred strategy might not accurately reflect the employee's capacity to tackle work–family conflict in such circumstances. Thus, the required aspect of home‐based telework due to the pandemic may also explain our nonsignificant findings; that is, while individuals with high segmentation preferences may prefer to keep work and private life as separate as possible (Kreiner, 2006), they may still be efficient in tackling violations and reducing domain dissatisfaction when they are required to adapt to home‐based telework.

The final major finding of our research comes from the investigation of both work and home‐related unfinished tasks in Study 2 (Model 2). First, the results support the domain‐specific mediation of unfinished tasks, indicating that boundary violations or interruptions in the domain relate to an increase in unfinished tasks, as the employee is required to tackle the interruption and, in turn, unfinished tasks relate to dissatisfaction in the same domain. The indirect relationships between work boundary violations and home satisfaction via home‐related unfinished tasks and between home boundary violations and work satisfaction via work‐related unfinished tasks were also supported. In other words, boundary violations create unfinished tasks in the other domain as well, providing a link to the domain dissatisfaction. Thus, it seems that employees may be unable or unwilling to tackle the unexpected demand from the other domain. For example, if an employee is interrupted while engaged in a work task by their child needing help with schoolwork, this could not only create an unfinished task in the work domain but may also create an unfinished task in the home domain if the employee is unable to give full attention to the child.

Our results also support the hypothesis that home boundary violations relate to satisfaction in the work domain via home‐related unfinished tasks. However, we were unable to support the relationship between work boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction via work‐related unfinished tasks. In light of the Zeigarnik effect (Zeigarnik, 1938), this would indicate that home‐related unfinished tasks remain cognitively active while the employee is engaged in the work domain to decrease satisfaction in the work domain. However, work‐related unfinished tasks may not be cognitively active (enough) to decrease home‐domain satisfaction. To further attest to this premise, our results support the relationship between work boundary violations and work satisfaction via home‐related unfinished tasks.

On the other hand, the relationship between home boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction via work‐related unfinished tasks was not supported. It is also noteworthy that unfinished tasks received the same average score in both domains (M = 2.34). Again, it seems that although interruptions to either work or home domains create unfinished tasks in both domains, the home‐related unfinished tasks may remain more cognitively active than unfinished tasks in the work domain. A possible explanation comes from previous literature, which found that the demands from the domain in which the employee is currently engaged have more salience than demands from the other domain (Golden, 2012). In other words, because employees are located at home, the home‐related unfinished tasks may seem more prominent and remain more cognitively active than work‐related unfinished tasks. This finding may also be (to some extent) specific to the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic, which forced the employees into home‐based telework for an extended period of time. Put differently, the cognitive prominence of home‐related demands and unfinished tasks may have been even further exacerbated by the fact that the employees (and their household members) were continuously located at home day after day and likely for most of the day.

The additional analyses also provided valuable insight regarding the role of gender and having children in the relationships examined. First, both Study 1 and 2 Model 1 and Model 2 results differentiate women without children from other groups. Specifically, Model 1 results showed a negative relationship between work boundary violations and home‐related satisfaction in both studies, and furthermore, the effect became nonsignificant in Model 2, indicating full mediation (Rucker et al., 2011) of unfinished tasks. Thus, it seems that teleworking women without children may prioritize the interrupting work tasks during the pandemic, increasing home‐related unfinished tasks, which in turn decreases satisfaction with investment in the home domain. Further attesting this notion is the observed positive relationship between home boundary violations and satisfaction with investment in the work domain, indicating that prioritization of interrupting work tasks may increase satisfaction with investment in the work domain.

Investigation of Model 2 also differentiates women with children, showing a nonsignificant relationship between work boundary violations and home‐related unfinished tasks, indicating that women with children may not be able to postpone or reject interrupting demands from the home domain. Furthermore, we observed a significant negative cross‐domain relationship between boundary violations and domain satisfaction, indicating that dissatisfaction of having to switch between interrupting tasks from the two domains can be observed, particularly after including unfinished tasks in the model. Lastly, we observed a nonsignificant relationship between work boundary violations and home‐related unfinished tasks and between home boundary violations and work‐related unfinished tasks for men with children. In comparison to women with children, this indicates that men may be able to postpone or reject home‐related unfinished tasks. In other words, the gender of the parent plays a role in the cross‐domain relationships between boundary violations and unfinished tasks. This finding is consistent with other studies, showing that women tend to take on more home‐related obligations (Chernyak‐Hai et al., 2021). Furthermore, our findings are in line with research in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic, showing a shift toward traditional gendered behavior when it comes to tackling family or home obligations and childcare (Shockley et al., 2020).

Practical implications

Speculating that telework may likely continue after the COVID‐19 pandemic, our findings may provide insight for practitioners and organizations on the pitfalls of telework and inform on how to make telework work for employees. As our findings indicate, employees may struggle with work and home boundary violations due to the collocation of work and home, increasing unfinished tasks in both domains and decreasing satisfaction with domain investment. Thus, it may be beneficial for employees and practitioners to develop strategies for managing the work–life boundary during home‐based telework in order to reduce boundary violations and unfinished tasks in both domains. Previous research on telework found that creating physical, temporal, and behavioral strategies helped employees maintain the work–home boundary (Basile & Beauregard, 2016). A recent study by Allen et al. (2020) provided detailed strategies that employees used to manage the work–life boundary during the pandemic. Examples of behavioral strategies include imitating the office routine, such as getting office‐ready in the morning and changing clothes when finished with work. From a temporal perspective, employees had success with setting a strict work time and determining a time to stop working. Lastly, creating a separate workspace or workstation enabled employees to create a physical boundary between work and private life.

Our findings indicate that setting a boundary in the home domain may be just as, if not more, critical. Employees should thus clearly communicate in the home domain when they are available and when they are not to be interrupted. Previous research also found that the flexibility associated with telework can allow employees to more efficiently tackle demands in both domains (Golden et al., 2006). Thus, practitioners and organizations should continue to allow for a certain amount of flexibility but should make sure that spatial flexibility does not over‐extend into temporal flexibility. For example, the flexibility of telework can allow the employee to finish an email late in the evening, tackling an unfinished task, but at the same time potentially interrupting another employee in their off‐job time. Thus, implementing an organizational policy or guidelines regarding telework (e.g. employees should not initiate work‐related communication after 6 p.m.) could provide additional structure to employees and facilitate employee satisfaction.

Furthermore, we speculate that telework may become more optional (or less often obligated) as countries gain control over the pandemic but much more widely available and established than it was prior to the pandemic. In other words, employees may be facing increased variability in teleworking days in the future. This increased variability may make boundary violations and interruptions more changeable from day to day. For example, on some days, an employee might be working from home alone while their partner is working from the office, and on other days they might both work from home. Thus, employees will likely benefit from creating well‐defined boundaries and reducing cross‐domain interruptions even as home‐based telework becomes optional.

Finally, employees and practitioners should pay special attention to the shift toward traditional gendered roles when it comes to private life demands. Shockley et al. (2020) found that the best strategy for dual‐earner couples is to alternate days of home‐based telework. Such a strategy may become increasingly available as home‐based telework becomes more optional and could potentially enable women with children to reduce the amount of interruptions from the home domain, decrease the amount of unfinished tasks, and increase satisfaction with work and home domain. Organizations, on the other hand, can facilitate such strategies by allowing the employees to determine when home‐based telework is best suited for them.

Limitations and future research

Our studies are not without limitations. Due to the flexible nature of telework (e.g. individuals can engage in work‐related tasks late in the evening to be then interrupted by the home domain), all study variables were assessed at the same time (before bed). Although similar methods have been used in previous daily research on telework (e.g. Delanoeije et al., 2019), a single measurement point at the end of the day resulted in the cross‐sectional nature of the daily measures. In addition, all variables in studies were assessed with self‐report measures, raising the issue of common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Thus, the results of the reported mediation analysis should be interpreted with some caution. Future studies may benefit by utilizing an event‐sampling approach (see Ohly et al., 2010) to separate the measurement of the variables to at least some extent. This could be done by, for example, asking the participants to answer questions regarding the work boundary violations scale when they feel that they have finished working and not at a pre‐determined time. Furthermore, to complement self‐reported scale measures, future research may benefit from asking the participants to keep track of and report the number of daily boundary violations for each domain.

In light of the null findings regarding segmentation preferences in our studies, future research may benefit from considering self‐efficacy in boundary management (see Lapierre et al., 2016) in addition to segmentation preferences. Additionally, previous research showed that boundary management strategies could be subject to change (Vaziri et al., 2020); however, they were regarded as a stable construct in our studies. Thus, future research may benefit from considering potential within‐person variability in boundary management preferences and strategies. Furthermore, our studies indicate that gender and having children play a role in the relationships examined; thus, future research may benefit from examining them in parallel with segmentation preferences. Finally, our results highlight the relevance of unfinished tasks when examining the work–life boundary outcomes, such as satisfaction with investment in the domain. Thus, future research examining work–life outcomes in the context of telework may benefit from considering unfinished tasks in both domains and further explore potential implications for the well‐being of employees.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national ethics regulations. Participants were fully informed about the aims of the study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency—ARRS (Javna Agencija za Raziskovalno Dejavnost RS) (grant numbers: J5‐9449 and the research program P5‐0062) and the Uni:docs Fellowship Programme for Doctoral Candidates (University of Vienna).

Kerman, K. , Korunka, C. , & Tement, S. (2022). Work and home boundary violations during the COVID‐19 pandemic: The role of segmentation preferences and unfinished tasks. Applied Psychology, 71(3), 784–806. 10.1111/apps.12335

[Correction added on 27 July 2021, after first online publication: The copyright line was changed.]

Funding information Uni:docs Fellowship Programme for Doctoral Candidates (University of Vienna); Javna Agencija za Raziskovalno Dejavnost RS, Grant/Award Numbers: J5‐9449, P5‐0062

ENDNOTE

The term “domain satisfaction” indicates satisfaction with investment in the domain.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw data related to the variables included in the manuscript are available to any qualified researcher upon request.

REFERENCES

- Allen, T. D. , Cho, E. , & Meier, L. L. (2014). Work–family boundary dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 99–121. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T. D. , Golden, T. D. , & Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(2), 40–68. 10.1177/1529100615593273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T. D. , Merlo, K. , Lawrence, R. C. , Slutsky, J. , & Gray, C. E. (2020). Boundary management and work‐nonwork balance while working from home. Applied Psychology, 70(0), 1–25. 10.1111/apps.12300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B. E. , Kreiner, G. E. , & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day's work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. The Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491. 10.2307/259305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baethge, A. , & Rigotti, T. (2013). Interruptions to workflow: Their relationship with irritation and satisfaction with performance, and the mediating roles of time pressure and mental demands. Work & Stress, 27(1), 43–63. 10.1080/02678373.2013.761783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baethge, A. , Rigotti, T. , & Roe, R. A. (2015). Just more of the same, or different? An integrative theoretical framework for the study of cumulative interruptions at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(2), 308–323. 10.1080/1359432X.2014.897943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basile, K. A. , & Beauregard, T. A. (2016). Strategies for successful telework: How effective employees manage work/home boundaries. Strategic HR Review, 15(3), 106–111. 10.1108/SHR-03-2016-0024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brixey, J. J. , Robinson, D. J. , Johnson, C. W. , Johnson, T. R. , Turley, J. P. , & Zhang, J. (2007). A concept analysis of the phenomenon interruption. Advances in Nursing Science, 30(1), E26–E42. 10.1097/00012272-200701000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carillo, K. , Cachat‐Rosset, G. , Marsan, J. , Saba, T. , & Klarsfeld, A. (2020). Adjusting to epidemic‐induced telework: Empirical insights from teleworkers in France. European Journal of Information Systems, 30(1–20), 69–88. 10.1080/0960085X.2020.1829512 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyak‐Hai, L. , Fein, E. C. , Skinner, N. , Knox, A. J. , & Brown, J. (2021). Unpaid professional work at home and work–life interference among employees with care responsibilities. The Journal of Psychology, 155(3), 356–374. 10.1080/00223980.2021.1884825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic Press. 10.4324/9780203771587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawis, R. V. , Lofquist, L. H. , & Weiss, D. J. (1968). A theory of work adjustment: A revision. In Minnesota studies in vocational rehabilitation. Industrial Relations Center, University Of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Delanoeije, J. , & Verbruggen, M. (2019). The use of work‐home practices and work‐home conflict: Examining the role of volition and perceived pressure in a multi‐method study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2362. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delanoeije, J. , & Verbruggen, M. (2020). Between‐person and within‐person effects of telework: A quasi‐field experiment. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(6), 795–808. 10.1080/1359432X.2020.1774557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delanoeije, J. , Verbruggen, M. , & Germeys, L. (2019). Boundary role transitions: A day‐to‐day approach to explain the effects of home‐based telework on work‐to‐home conflict and home‐to‐work conflict. Human Relations, 72(12), 1843–1868. 10.1177/0018726718823071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derks, D. , Bakker, A. B. , Peters, P. , & van Wingerden, P. (2016). Work‐related smartphone use, work–family conflict and family role performance: The role of segmentation preference. Human Relations, 69(5), 1045–1068. 10.1177/0018726715601890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound . (2020). Living, working and COVID‐19. Publications Office of the European Union

- Golden, T. D. (2012). Altering the effects of work and family conflict on exhaustion: Telework during traditional and nontraditional work hours. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(3), 255–269. 10.1007/s10869-011-9247-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golden, T. D. , Veiga, J. F. , & Simsek, Z. (2006). Telecommuting's differential impact on work‐family conflict: Is there no place like home? Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1340–1350. 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, D. A. , Griffin, M. A. , & Gavin, M. B. (2000). The application of hierarchical linear modeling to organizational research. In Klein K. J. & Kozlowski S. W. J. (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 467–511). Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Hülsheger, U. R. , Alberts, H. J. , Feinholdt, A. , & Lang, J. W. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 310–325. 10.1037/a0031313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, E. M. , Clark, M. A. , & Carlson, D. S. (2019). Violating work‐family boundaries: Reactions to interruptions at work and home. Journal of Management, 45(3), 1284–1308. 10.1177/0149206317702221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization . (2020). Teleworking during the COVID‐19 pandemic and beyond: A practical guide. Publications of the International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, A. C. , Meier, L. L. , Elfering, A. , & Semmer, N. K. (2020). Please wait until I am done! Longitudinal effects of work interruptions on employee well‐being. Work & Stress, 34(2), 148–167. 10.1080/02678373.2019.1579266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kossek, E. E. , Lautsch, B. A. , & Eaton, S. C. (2006). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work–family effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 347–367. 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, G. E. (2006). Consequences of work‐home segmentation or integration: A person‐environment fit perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 27(4), 485–507. 10.1002/job.386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, G. E. , Hollensbe, E. C. , & Sheep, M. L. (2009). Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work‐home interface via boundary work tactics. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 704–730. 10.5465/amj.2009.43669916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, L. M. , van Steenbergen, E. F. , Peeters, M. C. , & Kluwer, E. S. (2016). Juggling work and family responsibilities when involuntarily working more from home: A multiwave study of financial sales professionals. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(6), 804–822. 10.1002/job [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, S. (2009). Why is it so hard to do my work? The challenge of attention residue when switching between work tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(2), 168–181. 10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milasi, S. , González‐Vázquez, I. , & Fernández‐Macıas, E. (2020). Telework in the EU before and after the COVID‐19: Where we were, where we head to. Science for Policy Brief.

- Muthen, L. , & Muthen, B. (2017). Mplus version 8 user's guide. Muthen & Muthen.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration . (2020). Guidance on preparing workplaces for COVID‐19. US: Department of Labor.

- Ohly, S. , Sonnentag, S. , Niessen, C. , & Zapf, D. (2010). Diary studies in organizational research. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9, 79–93. 10.1027/1866-5888/a000009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson‐Buchanan, J. B. , & Boswell, W. R. (2006). Blurring boundaries: Correlates of integration and segmentation between work and nonwork. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 432–445. 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y. , & Jex, S. M. (2011). Work‐home boundary management using communication and information technology. International Journal of Stress Management, 18(2), 133–152. 10.1037/a0022759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer, C. , Syrek, C. , Ostwald, V. , Schuh, E. , & Antoni, C. H. (2019). Thieves of flow: How unfinished tasks at work are related to flow experience and wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 1641–1660. 10.1007/s10902-019-00149-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M. , MacKenzie, S. B. , Lee, J.‐Y. , & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. J. , & Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(2), 77–98. 10.1080/19312458.2012.679848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puranik, H. , Koopman, J. , & Vough, H. C. (2020). Pardon the interruption: An integrative review and future research agenda for research on work interruptions. Journal of Management, 46(6), 806–842. 10.1177/0149206319887428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rucker, D. D. , Preacher, K. J. , Tormala, Z. L. , & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, C. W. , Allan, B. , Clark, M. , Hertel, G. , Hirschi, A. , Kunze, F. , Shockley, K. , Shoss, M. , Sonnentag, S. , & Zacher, H. (2020). Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. 10.31234/osf.io/k8us2 [DOI]

- Shockley, K. M. , Clark, M. A. , Dodd, H. , & King, E. B. (2020). Work‐family strategies during covid‐19: Examining gender dynamics among dual‐earner couples with young children. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106, 15–28. 10.1037/apl0000857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieler, I. , Scheibe, S. , Stamov‐Roßnagel, C. , & Kappas, A. (2017). Help or hindrance? Day‐level relationships between flextime use, work–nonwork boundaries, and affective well‐being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(1), 67–87. 10.1037/apl0000153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G. M. , Cameron, L. , & Garrett, L. (2017). Alternative work arrangements: Two images of the new world of work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 473–499. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syrek, C. J. , & Antoni, C. H. (2014). Unfinished tasks foster rumination and impair sleeping—Particularly if leaders have high performance expectations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(4), 490–499. 10.1037/a0037127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrek, C. J. , Weigelt, O. , Peifer, C. , & Antoni, C. H. (2017). Zeigarnik's sleepless nights: How unfinished tasks at the end of the week impair employee sleep on the weekend through rumination. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(2), 225–238. 10.1037/ocp0000031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri, H. , Casper, W. J. , Wayne, J. H. , & Matthews, R. A. (2020). Changes to the work–family interface during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Examining predictors and implications using latent transition analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(10), 1073–1087. 10.1037/apl0000819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020). Timeline: WHO's COVID‐19 response https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactivetimeline?gclid=Cj0KCQiAzsz-BRCCARIsANotFgNe#event-71

- Zeigarnik, B. (1938). On finished and unfinished tasks. In Ellis W. D. (Ed.), A source book of gestalt psychology (pp. 300–314). Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company. 10.1037/11496-025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data related to the variables included in the manuscript are available to any qualified researcher upon request.