Abstract

Background

Advances in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) monitoring, greater number of available treatments and a shift towards tight disease control, IBD care has become more dynamic with regular follow ups.

Aims

We assessed the impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on outpatient IBD patient care at a tertiary centre in Melbourne. More specifically, we assessed patient satisfaction with a telehealth model of care, failure to attend rates at IBD clinics and work absenteeism prior to and during the pandemic.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective, qualitative analysis to assess our aims through an online survey. We invited patients who attended an IBD outpatient clinic from April to June 2020 to participate. This study was conducted at a single, tertiary referral hospital in Melbourne. The key data points that we analysed were patient satisfaction with a telehealth model of care and the effect of telehealth clinics on work absenteeism.

Results

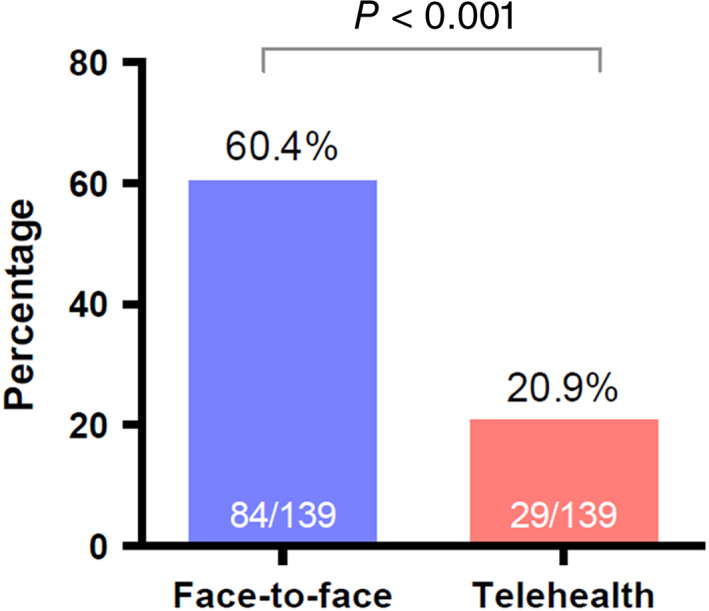

One hundred and nineteen (88.1%) patients were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the care received in the telehealth clinic. Eighty‐four (60.4%) patients reported needing to take time off work to attend a face‐to‐face appointment, compared to 29 (20.9%) patients who needed to take time off work to attend telehealth appointments (P < 0.001). Clinic non‐attendance rates were similar prior to and during the pandemic with rates of 11.4% and 10.4% respectively (P = 0.840).

Conclusions

Patients report high levels of satisfaction with a telehealth model of care during the COVID‐19 pandemic, with clinic attendance rates not being affected. Telehealth appointments significantly reduced work absenteeism when compared to traditional face‐to‐face clinics.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, telehealth, COVID‐19, outpatient clinic

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract. Australia has one of the highest rates of IBD in the world with a prevalence estimated at 197 persons per 100 000 population.1 With advances in disease monitoring, a greater number of available treatments (particularly biologic therapies) and a shift towards tight disease control to achieve ‘treat to target’ goals, IBD care has become more dynamic. There has been an increased emphasis on regular follow up and strict control of inflammation to prevent disease complications.2, 3, 4 The necessary increased frequency of physician appointments has led to growing burdens on patients and physicians.5 There are a multitude of barriers to patients attending these clinics, of which the financial implications of travel and time off work are an important factor.6 The morbidity associated with IBD affects national productivity with an approximate productivity loss of $360 million across Australia in 2012.7

Due to the chronic nature of this disease and rigorous testing and treating of patients, there are concerns regarding adherence and clinic non‐attendance. Non‐adherence rates of up to 72% have been reported in IBD patients. Reduced adherence leads to poor quality of life, increased complications and hospitalisations.8 This complex and chronic disease has significant impacts on patients, healthcare providers and the national economy. Innovative strategies to improve patient satisfaction, adherence and attendance at clinics have been investigated for many years with limited success.1

With the onset of the COVID‐19 global pandemic, health services across the world have had to adapt their models of care to allow for the ongoing provision of patient care for those with chronic diseases. In line with this, many IBD services across Melbourne have transitioned their face‐to‐face outpatient IBD care to a telehealth platform. The telehealth platform is one that utilises communication technology to connect with patients. This modality has previously been reserved largely for rural and remote patients.9 However, with a radical change in patient care settings due to the pandemic, this modality has been utilised for the majority of outpatient IBD care.

We aimed to assess the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on IBD patients receiving care at a major metropolitan hospital in Melbourne, Australia, from April to June 2020. More specifically, we aimed to assess patient satisfaction with the telehealth model of care, to review failure to attend rates at IBD clinics prior to and during the pandemic, to review rates of work absenteeism prior to and during the pandemic and explore patients' perceptions and adherence in regards to their immunomodulatory therapy in the setting of this pandemic.

Methods

All patients seen in the IBD outpatient clinic through telehealth between April and June 2020 at our centre were invited through text message to participate in an online survey. Prior to the survey, all IBD patients at this hospital had been emailed general information about COVID‐19 infection risk in IBD, which included information about medication adherence. The information provided encouraged patients to continue with all their prescribed medications unless specifically informed by their treating gastroenterologist.

The survey consisted of 15 questions which were divided into two components. The first set of questions assessed the impact that attending outpatient clinics had on work absenteeism during and prior to the pandemic, patient concerns with immunomodulator therapy in the setting of the COVID‐19 pandemic, patient adherence to immunomodulator therapy (which included thiopurines, methotrexate and biological therapies) and whether or not patients could be reassured by the information provided to them at their IBD telehealth clinics. The second set of questions was based on the validated short assessment of patient satisfaction questionnaire that is widely used to assess patient satisfaction with healthcare.10 We adapted these questions to assess patient satisfaction with their recent IBD telehealth appointments.

Lastly, we conducted a retrospective audit looking at IBD clinic attendance rates during the COVID‐19 pandemic from April to June 2020 following the transition to a telehealth model of care. We compared this to the average attendance rates from April to June in the 5 years prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic where appointments were conducted face to face.

Our study has been conducted with ethics approval gained from the Research Governance Unit at St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne.

Results

Four hundred eighty‐six patients who attended the telehealth clinic during the 3‐month period of April to June 2020 were invited to participate in the survey and 139 (28.6%) patients completed the survey. There are some questions that did not have responses by all participants and the total number of responses will be noted if they are fewer than 139.

Patient satisfaction with a telehealth service

One hundred and nineteen out of 135 (88.1%) patients were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the overall care they received in the telehealth clinic during this period. Furthermore, 115 out of 136 (84.6%) patients felt ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the choices they had in decisions regarding their own healthcare and 102 out of 135 (75.6%) patients felt their telehealth consultation was conducted for an appropriate duration.

Impact of clinic appointments on work absenteeism

A significantly lower proportion of patients reported needing to take time off to attend a telehealth appointment compared to attending a face to face consultation. Eighty‐four (60.4%) patients reported normally needing to take time off work to attend a face‐to‐face outpatient appointment, compared to only 29 (20.9%) patients who needed to take time off work to attend their telehealth outpatient appointment (P < 0.001; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients requiring time off work to attend clinic appointments: face‐to‐face and telehealth.

Perceptions and behaviours related to immunomodulatory therapy

Seventy‐four out of 136 (54.4%) patients were concerned that taking immunomodulatory treatment for their IBD increased their risk of COVID‐19. However, only five (3.6%) patients ceased or reduced the dose of their immunomodulatory medications without health professional advice. Sixty (43.2%) patients reported receiving information about immunomodulatory medication in relation to COVID‐19 (verbal, written or electronic) from their doctor or IBD nurse. Of the patients that did receive information about their therapy, 71.1% of patients were reassured regarding safely continuing their immunomodulatory therapy in the setting of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Clinic non‐attendance for telehealth and face‐to‐face‐based appointments

Between April and June 2020, 480 out of 536 (89.6%) patients attended their scheduled telehealth IBD outpatient appointment. This was compared to the average attendance rates for face‐to‐face IBD clinics for the same period in the preceding 5 years. This analysis revealed that an average of 397 patients attended their appointments out of an average of 448 (88.6%) scheduled appointments in each year from 2015 to 2019. This demonstrated a non‐attendance rate of 10.4% in the telehealth era as compared to 11.4% on average over the previous 5 years of face‐to‐face appointments (P = 0.840).

Discussion

The landscape of healthcare has been drastically altered by the COVID‐19 global pandemic. The effects of this pandemic have affected healthcare delivery, access and models of care. This has led to a change, perhaps forever, in how specialist outpatient care is delivered.11

Our results have demonstrated satisfaction rates of telehealth appointments are extremely high and attendance rates were not compromised following a switch to a telehealth model. High patient satisfaction and attendance rates lead to more cohesive medical care and superior disease control. Although most health services have had to rapidly alter their services and implement telehealth models to varying degrees, we can see at our centre that patients are satisfied with this approach. There are likely multiple reasons for high levels of patient satisfaction and attendance in our cohort including a relatively young age of patients seen in our clinics. This is likely to correlate to higher levels of comfort when using technology to access healthcare. Our data strongly support the use of the telehealth model as an adjunct for IBD care delivery. This model of care must receive ongoing support, funding and expansion during the current global pandemic. Furthermore, beyond this pandemic, the benefits of a telehealth model of care to outpatient clinics need to be considered as the preferred method for outpatient follow up for certain patients.

There is a significant difference in work absenteeism for patients attending face‐to‐face compared to telehealth clinics, with far fewer patients needing to take time off work to attend a telehealth clinic. Following the pandemic, reduced absenteeism and increased productivity will be vital to the recovery of the economy.

Our data also clearly demonstrate that the concerns regarding immunomodulatory therapy in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic were prevalent in our IBD population with over half of patients surveyed being concerned about the risks of immunomodulatory therapy in this context. However, despite this concern, we can also see that with further counselling by health professionals, the majority of patients could be reassured regarding the safety of immunomodulatory therapy, and only a minority of patients chose to stop or reduce immunomodulatory therapy without advice. High rates of patient concern regarding COVID‐19 but low rates of medication self‐cessation can also be seen in another single centred Australian study.12

Recent evidence assessing the impact of immunotherapy on COVID‐19 infection shows that corticosteroids are associated with increased rates of adverse outcomes.13 In this same database, 5‐ASA therapy, to a lesser extent, has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of severe complications and death from COVID‐19 infection, although the mechanism for this is unclear. Similar hypotheses have been postulated in regards to the thiopurines but there is no conclusive evidence thus far. The current recommendation from the Gastroenterological Society of Australia is to continue the minimum level of immunosuppression that would prevent disease flare.14 With the publication of these new findings, our advice to patients would be in line with this evidence. We would encourage our patients to continue immunomodulatory therapy, keeping general infection prevention strategies in mind, with an aim to prevent flare of disease and the need for corticosteroid use.

Previous studies have clearly demonstrated that patient adherence to therapy is boosted by regular emphasis on treatment benefits by their physicians.8 The perceptions relating to immunomodulatory therapy in the setting of the COVID‐19 pandemic along with non‐adherence that is often seen in IBD patients can both be negated by regular counselling and reassurance of patients by health professionals. This can be verbal, written or electronic information provided to the patient regarding their current treatment and the risks and benefits associated with therapy.

There are some limitations to our study. Our sample size was limited, with a total of 139 (28.6%) patients completing the survey of 486 patients invited. However, low response rates do not necessarily translate to a reduction in the validity of results.15, 16 Furthermore, there is likely to be reporting bias in the context of the collected data being a subjective measure of patient engagement, attendance and satisfaction. Additionally, our study was conducted at a single centre in metropolitan Melbourne, Australia. For more robust results to be obtained, a multi‐centre study to assess patient perceptions and satisfaction across various geographical and socioeconomic environments across Australia would be recommended. Furthermore, assessment of reasons for patients failing to attend clinic and gaining healthcare professional insight into the telehealth experience will further guide our understanding of this model of care and allow improvements to be made.

Conclusion

Patients in the present study reported high levels of satisfaction with a telehealth model for their IBD care during the COVID‐19 pandemic. This model of care was not associated with a higher rate of clinic non‐attendance. Telehealth appointments reduced work absenteeism when compared to traditional face‐to‐face clinic appointments, which will improve productivity and promote economic growth. We encourage healthcare providers and payers to consider the expansion of telehealth beyond the COVID‐19 pandemic as an acceptable way of delivering outpatient care.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the work of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Nurses at St Vincent's Hospital.

Funding: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EIet al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population‐based studies. Lancet 2017; 390: 2769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed Z, Sarvepalli S, Garber A, Regueiro M, Rizk MK. Value‐based health care in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019; 25: 958–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Haens GR. Top‐down therapy for IBD: rationale and requisite evidence. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 7: 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colombel JF, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, Lukas M, Baert F, Vaňásek Tet al. Effect of tight control management on Chrohn's disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomized, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018; 390: 2779–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunter J, Claridge A, James S, Chan D, Stacey B, Stroud Met al. Improving outpatient services: the Southampton IBD virtual clinic. Frontline Gastroenterol 2012; 3: 76–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallow JA, Theeke LA, Barnes ER, Whetsel T, Mallow BK. Free care is not enough: barriers to attending free clinic visits in a sample of uninsured individuals with diabetes. Open J Nurs 2014; 4: 912–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crohn's & Colitis Australia. Melbourne: Australian Crohn's and Colitis Association ; 2014. [cited 2020 Aug 26]. Available from URL: https://www.crohnsandcolitis.com.au/

- 8.Balaii H, Narab SO, Khanabadi B, Anaraki FA, Shahrokh S. Determining the degree of adherence to treatment in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2018; 11: 39–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orlando JF, Beard M, Kumar S. Systematic review of patient and caregiver's satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients' health. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0221848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawthorne G, Sansoni J, Hayes L, Marosszeky N, Sansoni E. Measuring patient satisfaction with health care treatment using the short assessment of patient satisfaction measure delivered superior and robust satisfaction estimates. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67: 527–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lees CW, Regueiro M, Mahadevan U. Innovation in IBD care during the COVID‐19 pandemic; results of a global telemedicine survey by international organisation for the study of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 805–808.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodsall TM, Han S, Bryant RV. Understanding attitudes, concerns, and health behaviours of patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 36: 1550–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenner EJ, Ungaro RC, Gearry RB, Kaplan GG, Kissous‐Hunt M, Lewis JDet al. Corticosteroids, but not TNF antagonists, are associated with adverse COVID‐19 outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: results from an international registry. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 481–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodsall TM, Costello SP, Bryant RV. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and implications for thiopurine use. Med J Aust 2020; 212: 490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morton SMB, Bandara DK, Robinson EM, Carr PEA. In the 21st century, what is an acceptable response rate? Aust N Z J Public Health 2012; 36: 106–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choung RS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Ziegenfuss JY, Beebe TJ, Zinsmeister ARet al. A low response rate does not necessarily indicate non‐response bias in gastroenterology survery research: a population‐based study. J Public Health 2012; 21: 87–95. [Google Scholar]