Abstract

Vascular endothelial injury is a hallmark of acute infection at both the microvascular and macrovascular levels. The hallmark of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is the current COVID‐19 clinical sequelae of the pathophysiologic responses of hypercoagulability and thromboinflammation associated with acute infection. The acute lung injury that initially occurs in COVID‐19 results from vascular and endothelial damage from viral injury and pathophysiologic responses that produce the COVID‐19–associated coagulopathy. Clinicians should continue to focus on the vascular endothelial injury that occurs and evaluate potential therapeutic interventions that may benefit those with new infections during the current pandemic as they may also be of benefit for future pathogens that generate similar thromboinflammatory responses. The current Accelerating COVID‐19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) studies are important projects that will further define our management strategies. At the time of writing this report, two mRNA vaccines are now being distributed and will hopefully have a major impact on slowing the global spread and subsequent thromboinflammatory injury we see clinically in critically ill patients.

Keywords: anticoagulant therapy, coagulopathy, COVID‐19, disseminated intravascular coagulation, endothelial cell, thrombosis

1. INTRODUCTION

The Corona VIrus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, a result of infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), is associated with a high morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients. One of the clinical issues that rapidly became apparent was that hospitalized patients are at an increased risk of thromboembolic events. The coagulopathy in COVID‐19 is due to a complex array of initial prothrombotic effects resulting in microvascular and macrovascular thrombosis, initially in the pulmonary circulation that can progress to life‐threatening acute lung injury, and potentially multiorgan dysfunction depending on the course of the disease. In this review, we discuss COVID‐19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation strategies.

2. HYPERCOAGULABILITY OF ACUTE INFECTIONS

Patients with acute infections react to invading microorganisms via an adaptive hemostatic response of hypercoagulability that occurs as part of a systemic inflammatory response. This normal host defense, termed thromboinflammation or immunothrombosis, initiates hemostatic activation and includes both humoral and cellular pathways.1, 2 In response to acute infections, a systemic inflammatory response syndrome ensues that has been previously described in acute bacterial infections producing septic shock. One of the critical complications of sepsis and septic shock is coagulopathy, defined as the laboratory‐based findings of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).3, 4 Multiorgan failure and death can occur during septic shock, and patients with DIC have a higher mortality. The coagulopathy due to sepsis described as DIC can be hemorrhagic and/or thrombotic and varies depending on the type of infection, associated organ injury, and host inflammatory responses.2, 3 The hypercoagulability of acute infection is associated with an increased fibrinogen level and thrombin generation that occurs in the milieu of microorganism induced acute endothelial injury that decreases levels of circulating anticoagulants, including protein C and antithrombin.2 As part of the progression of the infection, additional coagulation factors, including platelets, are consumed, and coagulation tests, including prothrombin times and potentially partial thromboplastin times, are prolonged. Therapy also depends on the course of the disease as it may progress from an initial hypercoagulability, the sine qua non of COVID‐19 infection, to subsequent DIC in prolonged intensive care unit stays and due to secondary bacterial infections, such as ventilator‐associated pneumonia.5

3. COVID‐19–ASSOCIATED COAGULOPATHY

Like all infection‐related coagulopathies, SARS‐CoV‐2–induced infection is associated with a high incidence of thromboembolic complications, as shown in Table 1.6 As previously described and depicted in Figure 1, the acute thromboinflammatory/immunothrombotic response following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection impairs tissue microcirculation causing injury initially in the lung that can cascade to other organs.6 The inflammatory response that occurs due to the lack of prior immunity releases multiple cytokines that may produce a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, often described as a cytokine storm in COVID‐19.7 Cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, interleukin‐6, and interleukin‐8, are released.8 Ranucci reported that increased fibrinogen production correlated with interleukin six levels in COVID‐19 patients with acute lung injury and mechanical ventilation demonstrating the link between inflammation and hypercoagulability in these patients.9 However, interleukin‐6 levels in septic patients due to bacterial infections are as high as 1000 pg/mL compared with the more modest interleukin‐6 levels in COVID‐19 of ~100 pg/mL within 14 days after onset of the infection.7, 8

TABLE 1.

COVID‐19: thrombosis data on anticoagulation prophylaxis

| Author | Country | Prophylaxis | Symptomatic VTE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klok23 | Netherlands | 2850 U nadroparin | 27% at 14d in ICU | 31% including arterial emboli |

| Middledorp33 | Netherlands | 2850 U nadroparin | 23% at 14d | |

| Helms24 | France | 40 mg enoxaparin | 11.7% | ARDS patients vs 2.1% in non COVID‐19 |

| Poissey25 | France | 40 mg enoxaparin | 20.6% | ICU patients v 7.5% influenza |

| Moll30 | USA | 40 mg enoxaparin | 9.3% at 14d |

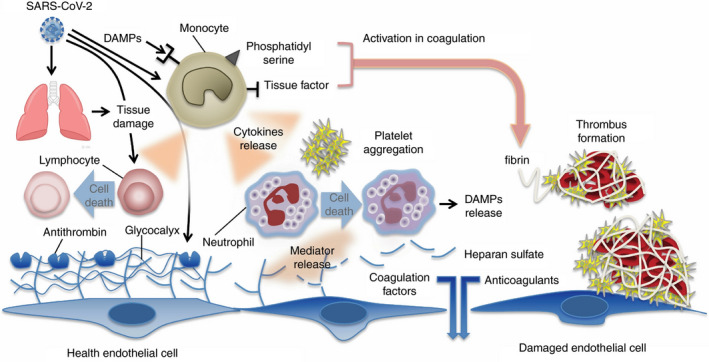

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms of coagulation activation and thromboinflammation in COVID‐19. Both pathogens (viruses) and damage‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from injured host tissue can activate monocytes. Activated monocytes release inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that stimulate neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, and vascular endothelial cells. Monocytes and other cells express tissue factor and phosphatidylserine on their surfaces and activate coagulation. Healthy endothelial cells maintain their antithrombogenicity by expressing glycocalyx and its binding protein antithrombin. Damaged endothelial cells change their properties to procoagulant following disruption of the glycocalyx and loss of anticoagulant proteins. From Iba T, Levy JH, et al with permission6

4. VASCULAR ENDOTHELIAL INJURY, ENDOTHELIOPATHY, AND ENDOTHELIALITIS IN COVID‐19

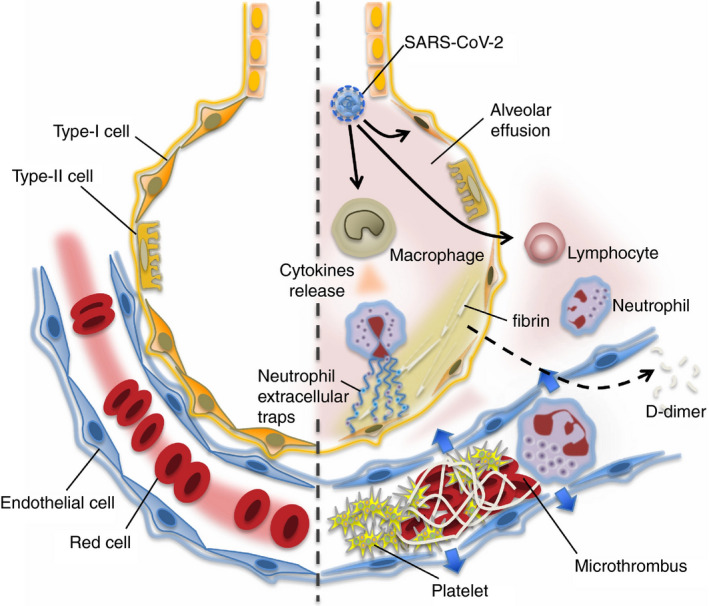

Acute vascular endothelial injury is another important hallmark of both acute infection and COVID‐19. Following exposure, the virus enters patients through nasopharyngeal airways that initially deliver the infection to the lung involving pulmonary vascular endothelium and alveoli. The SARS‐CoV‐2 virus's affinity for angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 and/or receptors in the vascular endothelium locally causes acute injury and activates local and then systemic inflammatory responses.5, 10 The lack of prior immunity allows the virus to propagate, which further amplifies the inflammatory response, with the recruitment of humoral and cellular responses as shown in Figure 2.6 The ensuing acute inflammatory response at the vascular and alveolar sites results in loss of the protective anticoagulant endothelial and glycocalyx interface, further contributing to the microvascular thrombotic sequelae that occur. This important pathophysiologic feature is consistent with other acute infections and DIC, and in COVID‐19 has been demonstrated to cause cell death/apoptosis.11 As a result of acute endothelial cell injury, other critical procoagulant factors, including von Willebrand factor, are also released that further augment the hypercoagulable response.8, 12 Severe COVID‐19 is also associated with relative deficiency of ADAMTS13, the critical cleavage enzyme for von Willebrand factor, and as a result results in larger, more procoagulant multimers of von Willebrand factor remaining in the circulation.13 Cell death and necrosis likely release multiple antigenic epitopes to the primed immune system that cause additional autoimmune responses that include the generation of antiphospholipid antibodies, and activate humoral amplification cascades including contact activation and complement.8

FIGURE 2.

In the undamaged lung (left), continuous blood flow and effective oxygenation are recognized. COVID‐19 infection causes an intense inflammatory reaction (right). The lung tissue damages are induced by uncontrolled activation of lymphocytes and possibly neutrophil activation (neutrophil extracellular trap [NET] formation). Increased pulmonary production of platelets is also involved in the defense process. In the damaged lung, the virulence of COVID‐19 or unabated inflammatory reaction causes pulmonary microthrombi, endothelial damage, and vascular leakage. The host intends to control the thrombus formation by vigorous fibrinolysis as lung has high fibrinolytic capacity. The fibrin‐degraded fragment (D‐dimer) spills into the blood and is detected in the blood samples. From Iba T, Levy JH et al with permission6

As previously described, the clinical manifestations of this virally induced acute lung injury produce an adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with acute hypoxemia, increased capillary permeability, and the characteristic findings of ground‐glass appearance on radiographic imaging due to increased capillary permeability and pulmonary edema.14, 15 Postmortem findings are also consistent with microvascular thrombotic sequela, as previously noted.11, 16 Reports have suggested the acute lung injury, hypoxemic respiratory failure, and acute bilateral pulmonary infiltrates may represent a novel pathologic entity. However, the finding of pulmonary microvascular thrombosis with acute infection was previously reported initially in 1983 in postmortem evaluations of 22 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome due to infectious causes, and was also noted in autopsies of patients who died from the SARS outbreak in 2003.17, 18 In critically ill COVID‐19 patients, the initial response appears to be a localized pulmonary inflammatory and microvascular thrombosis, but without systemic endothelial injury and potential for vasoplegia that commonly occurs with sepsis and/or septic shock. The variability in the inflammatory response to infection in COVID‐19 is consistent with acute infections that produce the cytokine storm, representing a systemic inflammatory response syndrome from the host response to the viral infection.

To compare the histopathology of the lung in COVID‐19 with SARS and H1N1 influenza, Hariri et al18 performed a systematic review that examined biopsies and autopsies that included 171 COVID‐19 patients from 26 articles, 287 H1N1 patients from 20 articles, and 64 SARS patients from eight articles. The authors noted that acute‐phase diffuse alveolar damage was similar among the groups and occurred in 88% of COVID‐19 patients compared with 90% H1N1 patients, and 98% of SARS patients. However, the incidence of pulmonary microthrombi was 58% of SARS patients and 57% of COVID‐19 compared with 24% of H1N1 influenza patients.18 It is not surprising that without any specific antiviral therapies, the unchecked disease process in COVID‐19 and SARS yielded thrombi with rates over two times higher than in H1N1 patients on biopsies and/or postmortems.

5. THROMBOINFLAMMATION AND IMMUNOTHROMBOSIS IN COVID‐19

Thromboinflammation is defined as thrombosis due to underlying inflammatory processes. This can occur in a wide range of clinical scenarios including acute infection, reperfusion injury associated with acute shock and resuscitation, and blood nonendothelial surface interfacing in biomaterial‐induced mechanical cardiopulmonary support devices.1 The hallmark of thromboinflammation is microvascular thrombosis‐associated inflammation, which is well‐recognized in the context of sepsis.19 The pathophysiology of thromboinflammation is due to vascular endothelial injury, with subsequent loss of endothelial and glycocalyx vascular interfaces that activate multiple cellular and humoral inflammatory system amplification pathways.1, 20 The humoral components of thromboinflammation also activate coagulation pathways, including contact factor activation, complement, and the fibrinolytic system.1, 2 Vascular injury and resulting thrombus formation are also produced by contributions from polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells during acute infections. Chemotaxis and chemokinesis of these inflammatory cells with activation not only release proteolytic enzymes, cell‐free DNA, neutrophil extracellular traps, and nuclear constituent histones that locally target the invading organisms but also activate additional inflammatory responses and enhance other prothrombotic pathways.19, 21 Cellular release of histones activates additional inflammatory responses and enhances other prothrombotic pathways of damage‐associated molecular patterns and pathogen‐associated molecular patterns that further cause localized endothelial injury at the initial infection site. This process has also been described as immunohemostasis.2

As COVID‐19 progresses to a systemic response, multiple cytokines further orchestrate the systemic response and development of multiorgan injury. The thromboinflammatory response to infection has been previously described as a sepsis‐induced coagulopathy, one of the many pathophysiologic responses that arise from acute infections, or more commonly described as disseminated intravascular coagulopathy associated with acute infections due historically to bacterial or fungal organisms. The first description in the literature of COVID‐19 as a thromboinflammatory response was in critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation due to acute lung injury that reported increased fibrinogen levels that correlated with increased interleukin‐6.9, 22

6. COAGULATION TESTING AND THROMBOTIC SEQUELAE FOR SARS‐COV‐2 INFECTION

The hypercoagulable response of COVID‐19 includes initially increased levels of D‐dimer that correlate with adverse outcomes and are used to guide higher dosing of anticoagulation in hospitalized patients at many institutions. Despite these findings, the levels in COVID‐19 are lower than those reported in classical sepsis‐induced DIC.10 Compared with standard DIC testing that includes decreased platelet counts and increased prothrombin times, most standard coagulation tests are usually initially relatively normal despite hyperfibrinogenemia, a finding that is different than acute bacterial sepsis. In SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, the initial site of entry into the lung with acute infection causes clot formation locally in the pulmonary microcirculation, resulting in hypoxemia and ventilation‐perfusion abnormalities. Thrombus formation that occurs in the small‐to‐mid‐size pulmonary arteries has a variable but potential progression to involve other organs causing multiorgan injury and microvascular and macrovascular thrombosis.11, 16 As a result, the coagulopathy of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection progresses from an initial localized microcirculatory thrombotic phase to a systemic response, depending on multiple factors, including the ability of the host to mount an immune response.

Clinical thrombosis in COVID‐19–associated coagulopathy is more commonly thrombotic than in sepsis‐induced coagulopathy, with a number of studies reporting the increased risk of thromboembolic events in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients as shown in Table 1. One of the issues when reviewing the early literature from China is the consideration that many of the initial reported cases were in patients who did not receive thromboprophylaxis. The more recent risk of thromboembolic complications in patients receiving standard dosing of both low molecular heparin and unfractionated heparin is shown in Table 1.

Some of the representative studies shown in Table 1 include a European cohort study reporting cumulative incidents of 27% confirmed venous thromboembolic complications at 14 days, with 31% combined arterial and venous events in patients with ARDS.23 Other studies in ARDS that compared COVID‐19 patients to other critically ill ICU patients also report increased thromboembolic event rates of 11.7% in COVID‐19–positive patients vs. 2.1% in the non–COVID‐19 ICU cohort.24 Additional reports from France noted the incidence of pulmonary emboli in ICU COVID‐19 patients to be three times higher than other critically ill patients with pneumonia (20.6% vs 6.1%).25 It is important to consider that thrombosis associated with COVID‐19 differs among reported studies particularly based on whether surveillance imaging was used to detect clinically silent thrombosis. Pooled data suggest an 8% pulmonary emboli incidence, but multiple factors may limit the interpretation.

7. FIBRINOLYTIC SHUTDOWN IN COVID‐19

Fibrinolytic shutdown (also called fibrinolysis inhibition) is a term popularized in trauma patients.26 Diagnosed by viscoelastic testing using thromboelastography (TEG systems) or thromboelastometry (ROTEM systems), it has also been reported to describe fibrinolysis inhibition in COVID‐19 as a risk factor for potential thromboembolic events. Fibrinolytic shutdown may be in part due to increased release of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI‐1), a finding that has been reported as a host defense response to infection, and increased PAI‐1 and tPA levels have been reported in COVID‐19 patients. Creel‐Bulos et al also reported fibrinolytic shutdown based on viscoelastic testing in 44% of critically ill patients with COVID‐19, with eight of nine patients (73%) developing clinically relevant thrombotic complications.27

Despite the evidence for diagnosis of fibrinolytic shutdown using viscoelastic measurement, critically ill COVID‐19 patients also have increased levels of D‐dimer, a fibrinolysis‐specific degradation product. This indicates that hyperfibrinolysis may be occurring locally throughout the microcirculation of the lung generating D‐dimer even as systemic fibrinolysis measured in standard viscoelastic testing appears normal using lysis at 30 minutes (LY30) on TEG, or lysis Index after 30 minutes on ROTEM. Viscoelastic testing evaluates actual macroclot lysis in vitro and can manifest a normal maximal clot firmness/ maximal amplitude, without evidence of lysis or correlation with D‐dimer levels, even if such breakdown is occurring in vivo.

8. ANTICOAGULATION IN COVID‐19 PATIENTS

Multiple guidance and guideline documents have published anticoagulation dosing strategies for inpatients, using heparin as the primary anticoagulant. Whether unfractionated heparin or low‐molecular‐weight heparin is used depends on multiple factors, including renal function. The benefit of low‐molecular‐weight heparin is standard dosing without the need to titrate and/or monitor coagulation levels. The optimal thromboprophylaxis strategy for hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 remains to be determined.28 Beyond the type of heparin used clinically is the ongoing question whether increasing anticoagulation levels to intermediate or full antithrombotic dosing improves outcomes in COVID‐19 patients. The role of antithrombotic therapy in COVID‐19 forms the basis of one of the platforms of the current Accelerating COVID‐19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) studies sponsored by the National Heart and Blood Institute (NHLBI). In all of ACTIV‐4 studies, one main objective is to determine whether the benefit of reducing thrombosis is offset by an increase in the bleeding risk.29 Recent retrospective studies from the United States note a lower incidence of thromboembolic events in patients receiving an adjusted dose of anticoagulation based on critical illness and biomarkers such as D‐dimers and fibrinogen.30 Retrospective data from one US institution in which all hospitalized patients received a standard dose thromboprophylaxis regardless of disease severity noted higher rates of thrombosis in critically ill ICU patients compared with patients on the ward, although the rate was lower than those reported from some European centers where a 25% lower dose of low‐molecular‐weight heparin was standardly used.30

The current Accelerating COVID‐19 ACTIV studies are important projects that will further define our management strategies. Of note is that in one of the randomized studies (ACTIV‐4a), evaluating efficacy of different intensity heparin doses, enrollment of critically ill ICU patients was paused in late December 2020 due to lack of efficacy of decreased organ free support at 21 days with a prespecified futility stopping threshold. Although more details are forthcoming, the enrollment of moderately ill COVID‐19–positive patients is continued. As a reminder, most current data are based on observational retrospective data analyses. Based on most guidance and guidelines, hospitalized patients should receive thromboprophylaxis and consider additional individualized adjusted dosing based on objective parameters rather than protocolized dosing adjustment. As with any anticoagulation strategy, bleeding is always an important consideration; major bleeding occurred in 2.3% of patients, even with standard dosing for VTE prophylaxis.31

9. SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS: PEDIATRIC AND OBSTETRICAL PATIENTS

Specific preexisting hemostatic imbalance poses unique considerations for both pediatric and obstetrical patients. In the hemostatic system of children, most coagulation factor levels are ~20% to 30% lower than adult levels.32 With COVID‐19 infections, due to their lower procoagulation factors levels, relatively normal endothelial function, and normal immune responses, children have better outcomes and fewer adverse effects compared with adults. However, some children develop hyperinflammatory responses that can cause host injury, a critical driver of endothelial injury, and subsequent coagulopathy. Control of the viral infection is limited by the lack of preexisting immunity and/or current specific antiviral therapy, similar to adults. This syndrome that mimics Kawasaki's disease is called the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, often abbreviated as MIS‐C.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has stated that pregnant women may be at an increased risk of COVID‐19–related illness, including ICU admission and acute lung injury requiring mechanical ventilation, and is supported by communications from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists who continue to follow reporting. Although current data in this patient population are limited, the relative risk is low, and they do not appear to have an increased risk of mortality compared with nonpregnant patients in the same age‐group (https://www.acog.org/en/News/News%20Releases/2020/06/ACOG%20Statement%20on%20COVID‐19%20and%20Pregnancy). However, pregnancy is a hypercoagulable state, with higher coagulation levels of fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, factor VII, and factor VIII, and increased levels of D‐dimers. One of the potential concerns is that pregnancy may have additive effects with COVID‐19 infection, increasing the potential for thromboembolic events. Further evaluation of the effects of COVID‐19 in this important patient group is required and is ongoing.

10. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Vascular endothelial injury is a hallmark of acute infection at both the microvascular and macrovascular levels. Without prior vaccines or without prior immunity, a major issue of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is the pathophysiologic responses associated with acute infection—hypercoagulability and thromboinflammation—that drive the disease process and ongoing worldwide surges. At the time of writing this report, both mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna are now being distributed and will hopefully have a major impact on slowing the global spread. However, clinicians should continue to focus on the vascular endothelial injury that occurs and evaluate potential therapeutic interventions, as these will benefit not only those with new infections during the current pandemic but also may be of benefit as future pathogens that generate similar thromboinflammatory responses emerge. The current Accelerating COVID‐19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) studies are important projects that will further define our management strategies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

JHL serves on research, data safety, or advisory committees for Instrumentation Labs, Merck, and Octapharma. TI provided research grants from Japan Blood Products Organization and JIMRO. LO and KMC have no COIs. JMC received personal fees from Bristol‐Myer Squibb, Abbott, Portola, and Pfizer. This study provided research funding to the institution from CSL Behring.

Levy JH, Iba T, Olson LB, Corey KM, Ghadimi K, Connors JM. COVID‐19: Thrombosis, thromboinflammation, and anticoagulation considerations. Int J Lab Hematol. 2021;43:29–35. 10.1111/ijlh.13500

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jackson SP, Darbousset R, Schoenwaelder SM. Thromboinflammation: challenges of therapeutically targeting coagulation and other host defense mechanisms. Blood. 2019;133(9):906‐918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delabranche X, Helms J, Meziani F. Immunohaemostasis: a new view on haemostasis during sepsis. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iba T, Levy JH, Wada H, et al. Differential diagnoses for sepsis‐induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(2):415‐419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iba T, Levy JH, Warkentin TE, et al. Diagnosis and management of sepsis‐induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(11):1989‐1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID‐19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135(23):2033‐2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iba T, Levy JH, Levi M, Thachil J. Coagulopathy in COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(9):2103‐2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Valle DM, Kim‐Schulze S, Huang HH, et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID‐19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1636‐1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iba T, Connors JM, Levy JH. The coagulopathy, endotheliopathy, and vasculitis of COVID‐19. Inflamm Res. 2020;69(12):1181‐1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranucci M, Ballotta A, Di Dedda U, et al. The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID‐19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1747‐1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iba T, Levy JH, Connors JM, Warkentin TE, Thachil J, Levi M. The unique characteristics of COVID‐19 coagulopathy. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID‐19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417‐1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy JH, Iba T, Connors JM. Vascular injury in acute infections and COVID‐19: everything old is new again. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2021;31(1):6‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancini I, Baronciani L, Artoni A, et al. The ADAMTS13‐von Willebrand factor axis in COVID‐19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(2):513‐521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iba T, Levy JH, Levi M, Connors JM, Thachil J. Coagulopathy of coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(9):1358‐1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh CH, de Wit K, Levy JH, et al. Hypercoagulability and coronavirus disease 2019‐associated hypoxemic respiratory failure: mechanisms and emerging management paradigms. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(6):e177‐e181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):120‐128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomashefski JF Jr, Davies P, Boggis C, Greene R, Zapol WM, Reid LM. The pulmonary vascular lesions of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Pathol. 1983;112(1):112‐126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hariri LP, North CM, Shih AR, et al. Lung histopathology in coronavirus disease 2019 as compared with severe acute respiratory syndrome and H1N1 influenza: a systematic review. Chest. 2021;159(1):73‐84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iba T, Levy JH. Inflammation and thrombosis: roles of neutrophils, platelets and endothelial cells and their interactions in thrombus formation during sepsis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(2):231‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iba T, Levy JH, Hirota T, et al. Protection of the endothelial glycocalyx by antithrombin in an endotoxin‐induced rat model of sepsis. Thromb Res. 2018;171:1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iba T, Levy JH. Derangement of the endothelial glycocalyx in sepsis. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(2):283‐294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connors JM, Levy JH. Thromboinflammation and the hypercoagulability of COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1559‐1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145‐147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089‐1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID‐19: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142(2):184‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore HB, Gando S, Iba T, et al. Defining trauma‐induced coagulopathy with respect to future implications for patient management: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(3):740‐747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creel‐Bulos C, Auld SC, Caridi‐Scheible M, et al. Fibrinolysis shutdown and thrombosis in a COVID‐19 ICU. Shock. 2021;55(3):316‐320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1859‐1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tremblay D, van Gerwen M, Alsen M, et al. Impact of anticoagulation prior to COVID‐19 infection: a propensity score‐matched cohort study. Blood. 2020;136(1):144‐147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moll M, Zon RL, Sylvester KW, et al. VTE in ICU patients with COVID‐19. Chest. 2020;158(5):2130‐2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al‐Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, et al. COVID‐19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489‐500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Achey MA, Nag UP, Robinson VL, et al. The developing balance of thrombosis and hemorrhage in pediatric surgery: clinical implications of age‐related changes in hemostasis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26:1076029620929092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van Haaps TF, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1995‐2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.