Abstract

We investigate the antecedents of subjective financial well-being and general well-being during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In an online survey conducted in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic with over 1000 Swedish participants we found that distrust in the government to cope with financial (but not healthcare) challenges of the pandemic was negatively related to the feeling of financial security. In a structural equation model, we also show that trust in government to deal with financial challenges of COVID-19 pandemic has a significant impact on general well-being through the mediating channel of financial well-being. In addition, trust in government to deal with healthcare challenges of COVID-19 pandemic has a significant direct impact on individuals’ general well-being. Our findings have important implications for public policy as they highlight the importance of citizens’ trust in well-functioning governmental institutions to help cope with not only healthcare, but also financial challenges of an ongoing pandemic.

Keywords: Financial well-being, Well-being, COVID-19, Trust, Risk perception

1. Introduction

How do major negative societal events influence the feelings and decisions of a whole population? Previous research in behavioral economics has shown that preferences are constructed on the basis of various contextual factors such as incidental affect, mood, or general well-being (Johnson and Tversky, 1983, Slovic, 1995) and people tend to rely on their affective reactions and mood when making decisions (Slovic et al., 2002a). These effects, however, have limited scope in normal everyday life (e.g., local effects of weather on stock trading; Hirshleifer and Shumway, 2003, Saunders, 1993), whereas large societal events such as the COVID-19 pandemic may impact a whole population with more similar responses across individuals. Some recent research shows that feelings of worry and distress have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fitzpatrick et al., 2020), while the effect on general (subjective) well-being is both small (Kivi et al., 2020) and large (Qiu et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2020), depending on sample.

In addition to direct health concerns, a potential source of negative feelings during a major crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic is the insecurity about the financial situation (Barrafrem et al., 2020). Financial well-being is very much about emotions such as fear and distress (Pixley, 2004, Pixley, 2012a). These types of negative emotions are also a prime reason for why people often fail to do economically what they know they should (Pixley, 2012b). In general, we expect that the increase in negative feelings across the population due to the COVID-19 pandemic is linked to a perceived lower financial security. However, for an event that affects an entire country or even the world, both feelings and well-being can be mitigated by factors such as trust in institutions and the government’s ability to suppress and handle uncertainties related to public health. Importantly, trust is directly intertwined with perceptions of personal and societal financial risk (Slovic, 1999). Distrust in institutions responsible for risk management has been shown to be linked to perceptions of unacceptably high risks. Moreover, both risk and trust are feeling-based heuristic judgments (the affect heuristic; Slovic et al., 2002b, Slovic and Västfjäll, 2010) – if it feels good, risk is low, and trust is high; if it feels bad, risk is high, and trust is low.

In this research, we ask how important trust or distrust in public institutions to deal with financial and healthcare challenges is for financial well-being during a sudden economic downturn. Moreover, we examine the mediating role of financial well-being in the relationship between these perceptions and the general well-being. Trust in government may potentially affect financial well-being, because a well-functioning safety net is important for individuals to feel secure when it comes to their finance, especially in times of unrest, like the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, trust is seen as a cornerstone to economic development (Algan and Cahuc, 2010). In particular, trust in government to deal with pandemic challenges may affect people’s perception of how vulnerable they are to financial shocks caused by the ongoing pandemic.

Financial well-being or satisfaction in regard to financial matters has been previously shown to have a significant impact on the quality of life, happiness, general well-being, mental health, and interpersonal relationships (Brüggen et al., 2017, Netemeyer et al., 2017). In this study, we used multiple-item measure of two facets of financial well-being (Lind et al., 2020): financial security and financial anxiety. Thus, financial well-being is defined here as (a) a sense of security about one’s own financial situation and (b) the lack of negative emotions (i.e., anxiety, worry) caused by financial matters.

1.1. The Swedish context and the current study

The first case of COVID-19 in Sweden was reported February 1 (World Health Organization, 2020a). On March 25, Swedish authorities issued statements recommending social distancing and working from home, but unlike in many other countries did not enact a general lockdown or make these measures legally binding, which attracted general criticism from many epidemiologists in the country and in the rest of the world (Henley, 2020a). An additional, yet voluntary, recommendation to “shelter in place” was also directed to adults aged 70 and older (Public Health Agency of Sweden, 2020). At the time of data collection, Sweden had 192 confirmed deaths per million (World Health Organization, 2020b).

At the same time, Stockholm Stock Exchange experienced a dramatic fall, during which OMX Stockholm 30 dropped about 31% in one month, between 19th of February (the all-time high value of OMX Stockholm 30) and 23rd of March (the lowest value of OMX Stockholm 30 since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic). After 23rd of March the stock market started to recover, however, on 23rd of April (the last day of data collection) the value of OMX Stockholm 30 was still about 18% below the level from 19th of February.

Taken together, the goal of this research is to examine how Swedes’ trust in official institutions’ ability to deal with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is related to financial and general well-being. We predict that trust in government to deal with financial issues is positively related to financial security and negatively related to financial anxiety. Through that channel it also has an impact on general well-being. In addition, as health issues can lead to loss of income (or part of it), we expect that trust in government to deal with healthcare issues is positively related to financial well-being (i.e., positively related to financial security and negatively related to financial anxiety) as well as to general well-being (i.e., satisfaction with life and subjective happiness).

2. Methods

We conducted an online survey with a general population of Sweden in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic, between 07th April and 23rd April 2020. Participants were recruited in collaboration with Origo Group1 and drawn from a sample of the general adult Swedish population previously included in their subject pool.

Financial well-being was measured using the Financial Well-Being Scale (Strömbäck et al., 2017, Strömbäck et al., 2020) which consists of two components: Financial Anxiety (based on the four items in anxiety factor in Fünfgeld and Wang, 2009) and Financial Security. People with high levels of financial well-being should consequently get a high score on Financial Security and low score on Financial Anxiety. We averaged the answers to items in each facet and obtained two variables, financial anxiety and financial security.2 Factor analysis confirmed the two-factorial nature of the Financial Well-Being Scale. Furthermore, while Financial Anxiety includes items that are relatively stable over time (e.g., I get unsure by the lingo of financial experts), items in Financial Security are likely to be more time specific (e.g., I feel confident about my financial future). Thus, the Financial Well-Being Scale measures both state- and trait-related factors related to subjective financial well-being. This makes Financial Security more likely to be affected by situational context (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic) than Financial Anxiety. The Cronbach’s alpha for Financial Anxiety and Financial Security is 0.80 and 0.90 respectively.

We asked participants about their trust in government’s ability to handle economic and healthcare challenges that Sweden faces during the pandemic. Participants answered on a seven-point scale ranging from “no trust” to “a lot of trust”. Furthermore, we asked participants about perceived risk that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has on their economic situation and health status. Participants answered on a seven-point scale ranging from “no risk at all” to “very high risk”. While significant, the Pearson’s correlation coefficients show that the correlation between the risk perception in the financial and health domain was weak (), but the correlation between trust in government related to financial and healthcare challenges was strong ( 0.81).

Participants responded to the five-item (“Big Five”) financial literacy scale (Lusardi, 2011, Lusardi and Mitchell, 2008). This scale measures individual differences in knowledge about compound interest, inflation, risk diversification, stock market, and loans. A higher value of financial literacy indicates a better knowledge of financial concepts. In addition, we collected information about respondent’s age, gender, education, and household’s gross income. Lastly, we asked participants if their income decreased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

General well-being has two components: the affective component and the cognitive (judgmental) component (Diener, 1984). While correlated, the two components are distinct from each other; the affective component captures individuals’ emotional reactions to events that might be temporary. The cognitive component captures individuals’ satisfaction with life, which is a more long-term evaluation of how one is doing in relation to a subjective standard. Thus, to measure the affective component of general well-being, we use the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999) and to measure the cognitive component of general well-being we use the Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985). Satisfaction with Life does not make distinction between different life domains, such as health, wealth, or family, but rather allows individuals to weigh them subjectively. The Cronbach’s alpha for Subjective Happiness Scale and The Satisfaction with Life Scale is 0.83 and 0.93 respectively.

In order to inspect the relationship between financial well-being and trust we conduct a series of linear regressions with robust standard errors (MacKinnon and White, 1985).3 We use financial anxiety and financial security as dependent variables. We complement linear regressions with mediation analysis, in which we investigate the mediating effect of financial security and anxiety on general well-being.

3. Results

The online survey was answered by 1021 respondents. The mean age was 48 years and 50.1% of respondents were female. Almost every fourth respondent (23.6%) reported that they lost at least a small part of their income during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean values and standard deviations of the variables used in the study.

| Variable | Mean/Proportion (Std) |

|---|---|

| Female | 50.15% |

| Age | 47.60 (15.67) |

| Education: | |

| - Primary education | 7.05% |

| - Secondary education | 39.37% |

| - Higher education, less than 3 years | 21.06% |

| - Higher education, 3 years or more | 32.52% |

| Household income (median category) | 35 000 sek - 44 999 sek |

| Trust in government: finance | 4.12 (1.81) |

| Trust in government: healthcare | 4.18 (1.81) |

| Financial risk | 3.58 (1.79) |

| Health risk | 4.10 (1.59) |

| Financial literacy | 2.57 (1.37) |

| Financial anxiety | 2.37 (0.93) |

| Financial security | 2.85 (1.22) |

| Satisfaction with life | 2.96 (1.01) |

| Subjective happiness | 4.37 (1.25) |

Note: Standard deviation in the brackets where applicable. Household income is an ordinal variable and represents monthly gross income of a household. It takes values from 1 (less than 15 000 sek) to 6 (55 000 sek or more). Trust variables take values between 1 (low trust) and 7 (high trust). Risk variables take values between 1 (low risk) and 7 (high risk). Financial literacy takes values between 0 (low literacy) and 5 (high literacy). Financial anxiety takes values between 1 (low level of anxiety) and 5 (high level of anxiety). Financial security takes values between 1 (low level of security) and 5 (high level of security). Satisfaction with life takes values between 1 (low satisfaction) and 5 (high satisfaction). Subjective happiness takes values between 1 (low happiness) and 7 (high happiness).

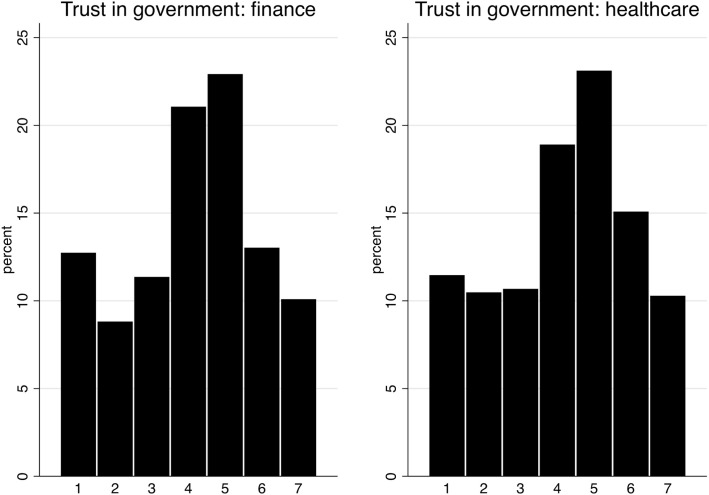

Fig. 1 shows the percentage of respondents who reported respective levels of trust in government related to financial and healthcare issues. The variables have similar distributions. In both cases, the mode is 5 which reflects relatively high levels of trust. Thus, we conclude that trust in general is quite high, but that there is considerable individual variation.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of trust in government related to financial and healthcare issues.

If we examine general and financial well-being, we find that the correlations between financial well-being measures and general well-being have moderate correlation, while subjective happiness and satisfaction with life are strongly correlated (Table 2). Thus, financial well-being and general well-being are correlated, yet distinct, constructs which warrants a separate analysis of the measures.

Table 2.

Pairwise correlations between well-being measures used in the study.

| Variables | Financial anxiety | Financial security | Subjective happiness | Satisfaction with life | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial anxiety | 1.000 | ||||

| Financial security | −0.409⁎⁎⁎ | 1.000 | |||

| Subjective happiness | −0.357⁎⁎⁎ | 0.472⁎⁎⁎ | 1.000 | ||

| Satisfaction with life | −0.334⁎⁎⁎ | 0.553⁎⁎⁎ | 0.704⁎⁎⁎ | 1.000 | |

Note: Financial anxiety takes values between 1 (low level of anxiety) and 5 (high level of anxiety). Financial security takes values between 1 (low level of security) and 5 (high level of security). Subjective happiness takes values between 1 (low happiness) and 7 (high happiness). Satisfaction with life takes values between 1 (low satisfaction) and 5 (high satisfaction).

p .

3.1. Trust and financial well-being

We investigate the link between financial well-being (i.e., financial security and financial anxiety) and trust in government to help individuals deal with potential challenges related to COVID-19 in a regression framework. Table 3 shows the results from linear regressions in which we use financial anxiety and financial security as outcome variables representing financial well-being, and trust in official institutions as the regressor of interest.4 Overall, we find that trust in government to deal with financial issues is positively related to the feeling of financial security, while there is no statistically significant relationship between trust in government to deal with healthcare issues and financial security. Moreover, we see no significant relationship between trust in government and financial anxiety. These results are robust to the inclusion of individual differences such as financial literacy, age, gender, household income, education as shown in Models 2 and 4. In Models 2 and 4 we also include individuals’ perceptions of the risk of COVID-19 to impact their financial situation or health status. We find that not only perceived financial risks but also health risks caused by an ongoing pandemic are negatively related to one’s financial well-being.

To summarize, we find that trust in government to deal with financial challenges related to COVID-19 pandemic is positively related to financial security but not financial anxiety. One of the reasons for this difference can be that the items used to measure financial security capture temporal state feelings, while the items used to measure financial anxiety are more likely to capture trait features of the individual, which are likely to be less affected by the pandemic. The results show that an individual with an average of financial security score (2.85), whose trust level in the government to deal with financial challenges increases from very low to very high, will experience an increase of approximately 25 percent in financial security. In a similar vein, for an individual with an average score of financial anxiety (2.37), moving from very low trust to very high trust in government to deal with financial challenges of the pandemic will be associated with a decrease of approximately 2 percent in financial anxiety. Put differently, an increase in trust in government to deal with financial issues by one standard deviation is related to the increase in financial security by 0.172 standard deviations and decrease in financial anxiety by 0.017 standard deviations. In order to understand the relative magnitude of this effect we compare standardized beta coefficients and find that trust in government to deal with financial issues has greater impact on the feeling of financial security than other factors such as financial literacy or education.5 This shows that by increasing trust among their citizens, governments may have a significant impact on individuals’ financial well-being particularly due to the increased feeling of financial security. In contrast, trust in government to deal with healthcare challenges related to COVID-19 pandemic is not significantly related to financial well-being. This is surprising given that higher perceived healthcare risks are connected to lower financial well-being.

Table 3.

The relationship between trust in government and financial well-being. Linear regression models.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial security | Financial security | Financial anxiety | Financial anxiety | |

| Trust in gov.: finance | 0.164⁎⁎⁎ | 0.117⁎⁎⁎ | −0.035 | −0.009 |

| (0.037) | (0.032) | (0.030) | (0.029) | |

| Trust in gov.: healthcare | 0.004 | −0.020 | −0.012 | 0.004 |

| (0.037) | (0.032) | (0.031) | (0.029) | |

| Financial risk | −0.135⁎⁎⁎ | 0.109⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.021) | (0.017) | |||

| Health risk | −0.077⁎⁎⁎ | 0.069⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.024) | (0.020) | |||

| Financial literacy | 0.115⁎⁎⁎ | −0.081⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.028) | (0.022) | |||

| Household income | 0.184⁎⁎⁎ | −0.062⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.021) | (0.017) | |||

| Female | −0.327⁎⁎⁎ | 0.091 | ||

| (0.071) | (0.056) | |||

| Age | 0.008⁎⁎⁎ | −0.010⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| Educ.: Secondary | 0.222 | −0.300⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.145) | (0.112) | |||

| Educ.: University 3 years | 0.274⁎ | −0.408⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.155) | (0.118) | |||

| Educ.: University 3 years | 0.379⁎⁎ | −0.313⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.151) | (0.116) | |||

| Constant | 2.156⁎⁎⁎ | 1.804⁎⁎⁎ | 2.562⁎⁎⁎ | 2.902⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.100) | (0.223) | (0.082) | (0.180) | |

| Observations | 1021 | 1021 | 1021 | 1021 |

| R-squared | 0.061 | 0.294 | 0.008 | 0.165 |

Note: Robust standard errors (MacKinnon and White, 1985) in parentheses. VIF for the two explanatory variables related to trust in government range from 2.89 (Model 1 and Model 3) to 2.93 (Model 2 and Model 4) suggesting no problems with strong multicollinearity. Outcome variables are listed on the top of each column. Financial anxiety takes values between 1 (low level of anxiety) and 5 (high level of anxiety). Financial security takes values between 1 (low level of security) and 5 (high level of security). Trust in government variables take value between 1 (low trust) and 7 (high trust) and indicate trust in governmental institutions to cope with financial/health challenges of COVID-19 pandemic; Financial risk and health risk take value between 1 (low perceived risk) and 7 (high perceived risk) and indicate perceived risk that COVID-19 pandemic has on one’s own financial situation and health status; Financial literacy takes values between 0 (low fin. literacy) and 5 (high fin. literacy). Household income is an ordinal variable and represents monthly gross income of a household where the lowest category is “less than 15 000 SEK” and the highest category is “55 000 SEK or more”; Reference category for Female is male and for Education is primary education.

p 0.01.

p 0.05.

p 0.1.

3.2. The mediating role of financial well-being on general well-being

Up until this point, we have focused on financial well-being of individuals. However, as evidenced by the moderate correlation coefficients, financial well-being is only one of the components of general well-being. We therefore conducted a mediation analysis to investigate if trust in government to deal with financial and healthcare related issues during COVID-19 pandemic affects general well-being. We allowed for direct effects and indirect mediation by financial security and financial anxiety. We use the Satisfaction with Life and Subjective Happiness measures as proxy for general well-being (Diener, 1984). We conducted a mediation analysis using structural equation model with bootstrapped standard errors (1000 replications). The model assumed three covariance connections: between the two trust variables, between the disturbances of two financial well-being variables, and between the disturbances of two general well-being variables.6

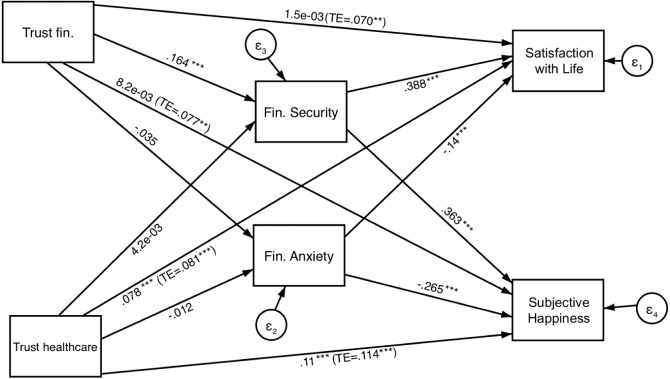

The results from our model estimations are presented in Fig. 2. We find that trust in government to deal with financial challenges of COVID-19 pandemic is directly related to financial security and through that channel is indirectly related to satisfaction with life (total effect, ) and subjective happiness (total effect, ). While trust in government to deal with healthcare challenges of COVID-19 pandemic is not related to financial well-being, it has a direct relation to general well-being (i.e., satisfaction with life, total effect, ; and subjective happiness, total effect, ).7 In sum, for an individual with an average score of satisfaction with life (2.96), moving from very low trust to very high trust in government to deal with financial (healthcare) challenges of the pandemic will be associated with an increase of approximately 14 (16) percent in satisfaction with life. In turn, for an individual with an average score of subjective happiness (4.37), moving from very low trust to very high trust in government to deal with financial (healthcare) challenges of the pandemic will be associated with an increase of approximately 11 (16) percent in subjective happiness. To conclude, trust in government to deal with both financial and healthcare challenges during a pandemic can significantly contribute to individuals’ improved general well-being by impacting both its cognitive and emotional aspects.

Fig. 2.

The impact of trust in government on general well-being and the mediating role of financial well-being. Note: Total effects (i.e., direct + indirect effects) are given in the brackets. Standard errors were calculated using bootstrap with 1000 replications. *** p 0.01, ** p 0.05, * p 0.1. The model assumed three covariance connections: between the two trust variables, between the disturbances of the two financial well-being variables, between the disturbances of the two general well-being variables. These connections are not shown for the sake of the clarity of the figure.

To summarize, trust in government to deal with financial challenges of COVID-19 pandemic is directly related to financial well-being as it affects the feeling of financial security. Through that channel it is also indirectly related to general well-being (both satisfaction with life and subjective happiness). In contrast, trust in government to deal with healthcare challenges of COVID-19 pandemic is unrelated to financial well-being but is directly related to general well-being (both satisfaction with life and subjective happiness).

4. Discussion and conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic - a global threat to both individuals’ health and finance, is likely to instigate a downward spiral of financial and general well-being. Severe impediments to the daily life such as social distancing rules, restrictions on travel and social gatherings, as well as strict lockdowns can further aggravate negative feelings. In addition, in the face of increasing numbers of cases and deaths, trust levels in authorities’ capabilities to deal with an ongoing crisis may deteriorate. This has been the case in Sweden, due to a sharp surge in COVID-19 related deaths. The trust in authorities’ handling the crisis caused by COVID-19 pandemic declined from 63% in April 2020 to 45% in June 2020 (Henley, 2020b). Thus, it is particularly important to assess how changes in trust are associated with financial and general well-being.

We investigated the relationship between trust in governmental institutions to deal with financial and healthcare challenges and the financial and general well-being in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings show that distrust in government to deal with financial issues caused by ongoing pandemic is directly related to feelings of financial insecurity. This, in turn, has a negative impact on satisfaction with life and subjective happiness. In addition, distrust in government to deal with healthcare issues caused by ongoing pandemic is directly related to lower general well-being (i.e., satisfaction with life and subjective happiness), but not financial well-being. In addition, our results show that perceptions of risks related to financial and health matters are relevant for financial well-being. Potentially, individuals are afraid that if they contract with the sickness, they will not be able to provide financial support for their households.

Our study contributes to findings on the important connection between trust and welfare (e.g., Knack and Keefer, 1997, Putnam et al., 1994, Zak and Knack, 2001). Simply put, our economy works because we trust each other and our institutions. We show that, in the context of an unforeseen crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, trust in social institutions is likely to play an important role in how well a country and its citizens recover. Not only from a health perspective but also from a financial and general well-being perspective. While our study focuses on trust in social institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on financial and general well-being at the individual level, previous studies have explored the importance of trust on firm and stocks at the market level. For example, Mazumder (2020) found that in the USA firms headquartered in the states with high social trust perform better during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, our study extends such findings by showing that trust, in our case in official institutions, is related to well-being at the individual level.

During the COVID-19 pandemic most governments have had a key focus on bolstering the healthcare system to be able to cope with individuals affected by sickness and trying to stop the spread of the disease. Our study shows that while possibly overlooked during a pandemic, the trust in well-functioning financial governmental institutions has an important impact on general well-being of citizens through the channel of financial well-being. Thus, in the face of a sudden crisis it is important that governments do not neglect the long run opportunity costs that a too one-sided policy focus on containment of the virus might have on welfare if no measures to revitalize financial well-being is taken.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kinga Barrafrem: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Gustav Tinghög: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Daniel Västfjäll: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Origo Group (www.origogroup.com) is a Swedish research company that specializes in data collection for national and international surveys. We hired them to collect a representative sample (based on age and gender in the Swedish adult population) of participants for our online experiment.

The survey questions can be found in the Supplementary Material.

MacKinnon and White (1985) standard errors used in the analysis are the most commonly used robust standard error estimator.

The same regression models but with general well-being (i.e., satisfaction with life and subjective happiness) as outcome are presented in the Supplementary Material. We find that trust in government to deal with healthcare challenges related to COVID-19 pandemic is positively related to general well-being. In contrast, trust in government to deal with financial challenges related to COVID-19 pandemic seems to have no significant relationship with general well-being.

Standardized beta coefficients for Table 3 are presented in the Supplementary Material.

We find that each of the covariances was statistically significantly different from zero.

The detailed list of direct and indirect effects can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2021.100514.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article.

Supplementary materials for ”Trust in the government increases financial well-being and general well-being during COVID-19”.

References

- Algan Y., Cahuc P. Inherited trust and growth. Amer. Econ. Rev. 2010;100(5):2060–2092. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.5.2060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrafrem K., Västfjäll D., Tinghög G. Financial well-being, COVID-19, and the financial better-than-average-effect. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüggen E.C., Hogreve J., Holmlund M., Kabadayi S., Löfgren M. Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2017;79:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984;95(3):542–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons R.A., Larsen R.J., Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick K.M., Drawve G., Harris C. Facing new fears during the COVID-19 pandemic: The State of America’s mental health. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020;75 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fünfgeld B., Wang M. Attitudes and behaviour in everyday finance: evidence from Switzerland. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2009;27(2):108–128. doi: 10.1108/02652320910935607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henley J. 2020. Critics question Swedish approach as coronavirus death toll reaches 1, 000. The Guardian. Retrieved October 11 from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/15/sweden-coronavirus-death-toll-reaches-1000. [Google Scholar]

- Henley J. 2020. Swedes rapidly losing trust in Covid-19 strategy, poll finds. The Guardian. Retrieved October 11 from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/26/swedes-rapidly-losing-trust-in-covid-19-strategy-poll-finds. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer D., Shumway T. Good day sunshine: Stock returns and the weather. J. Finance. 2003;58(3):1009–1032. doi: 10.1111/1540-6261.00556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E.J., Tversky A. Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983;45(1):20–31. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kivi M., Hansson I., Bjälkebring P. Up and about: Older adults’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Swedish longitudinal study. J. Gerontol.: Ser. B. 2020 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knack S., Keefer P. Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q. J. Econ. 1997;112(4):1251–1288. doi: 10.1162/003355300555475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lind T., Ahmed A., Skagerlund K., Strömbäck C., Västfjäll D., Tinghög G. Competence, confidence, and gender: The role of objective and subjective financial knowledge in household finance. J. Fam. Econom. Issues. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09678-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A., 2011. Americans’ financial capability. National bureau of economic research working paper series, No. 17103. 10.3386/w17103. [DOI]

- Lusardi A., Mitchell O.S. Planning and financial literacy: How do women fare? Amer. Econ. Rev. 2008;98(2):413–417. doi: 10.1257/aer.98.2.413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S., Lepper H.S. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indicat. Res. 1999;46(2):137–155. doi: 10.1023/A:1006824100041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon J.G., White H. Some heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimators with improved finite sample properties. J. Econometrics. 1985;29(3):305–325. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(85)90158-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder S. How important is social trust during the COVID-19 crisis period? Evidence from the Fed announcements. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer R.G., Warmath D., Fernandes D., Lynch J.G., Jr. How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. J. Consum. Res. 2017;45(1):68–89. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucx109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pixley J. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2004. Emotions in Finance: Distrust and Uncertainty in Global Markets. [Google Scholar]

- Pixley J. second ed. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2012. Emotions in Finance: Booms, Busts and Uncertainty. [Google Scholar]

- Pixley J. Routledge; 2012. New Perspectives on Emotions in Finance: The Sociology of Confidence, Fear and Betrayal, Vol. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Sweden J. 2020. If you are 70 or over – limit close contact with other people. Retrieved October 11 from https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/0370ba3bd2cb48358e2bfc1156a32cad/faktablad-covid-19-70-ar-engelska.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D., Leonardi R., Nanetti R.Y. Princeton University Press; 1994. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry. 2020;33(2) doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders E.M. Stock prices and wall street weather. Amer. Econom. Rev. 1993;83(5):1337–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P. The construction of preference. Amer. Psychol. 1995;50(5):364–371. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.50.5.364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P. Trust, emotion, sex, politics, and science: Surveying the risk-assessment battlefield. Risk Anal. 1999;19(4):689–701. doi: 10.1023/A:1007041821623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P., Finucane M., Peters E., MacGregor D.G. Rational actors or rational fools: Implications of the affect heuristic for behavioral economics. J. Socio-Econom. 2002;31(4):329–342. doi: 10.1016/S1053-5357(02)00174-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P., Finucane V., Peters E., Macgregor D.G. In: Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgement. Gilovitch T., Griffin D., Kahneman D., editors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. The affect heuristics. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P., Västfjäll D. Affect, moral intuition, and risk. Psychol. Inquiry. 2010;21(4):387–398. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2010.521119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strömbäck C., Lind T., Skagerlund K., Västfjäll D., Tinghög G. Does self-control predict financial behavior and financial well-being? J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 2017;14:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2017.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strömbäck C., Skagerlund K., Västfjäll D., Tinghög G. Subjective self-control but not objective measures of executive functions predicts financial behavior and well-being. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 2020;27 doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization C. 2020. COVID-19 Situation report no. 12. Retrieved October 11 from www.who.int: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200201-sitrep-12-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=273c5d35_2. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization C. 2020. COVID-19 Situation report no. 94. Retrieved October 11 from www.who.int: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200423-sitrep-94-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=b8304bf0_4. [Google Scholar]

- Zak P.J., Knack S. Trust and growth. Econ. J. 2001;111(470):295–321. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.00609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials for ”Trust in the government increases financial well-being and general well-being during COVID-19”.