Abstract

Advances in nanoscale directed assembly strategies have enabled researchers to analogize atomic assembly via chemical reactions and nanoparticle assembly, creating a new nanoscale “periodic table.” We are just beginning to realize the nanoparticle equivalents of molecules and extended materials and are currently developing the ground rules for creating programmable nanometer-scale coordination environments. The ability to create a diverse set of nanoscale architectures from one class of nanoparticle building blocks would allow for the synthesis of designer materials, wherein the physical properties of a material could be predicted and controlled a priori. Our group has taken the first steps toward this goal and developed a means of creating tailorable assembly environments using DNA-nanoparticle conjugates. These nanobioconjugates combine the discrete plasmon resonances of gold nanoparticles with the synthetically controllable and highly selective recognition properties of DNA. Herein, we elucidate the beneficial properties of these materials in diagnostic, therapeutic, and detection capabilities and project their potential use as nanoscale assembly agents to realize complex three-dimensional nanostructures.

Introduction

The modern field of nanotechnology has undergone rapid growth over the past decade, and some of the early advances in the development of nanomaterials are just becoming part of major applications. Nanostructures are now used extensively in the fields of catalysis, electronics, photonics, and medicine.1–6 They are used in low-tech applications, such as coatings and paints, and in high-tech applications, including components for powerful new medical diagnostic and therapeutic tools. Although we are still far from the dream articulated by U.S. President Clinton when launching the National Nanotechnology Initiative in 2000—when he imagined materials with 10 times the strength of steel at a fraction of the mass, and a device the size of a sugar cube that could contain all the information in the Library of Congress—it is clear that major opportunities still exist, and this field is not simply a fad but rather one that eventually will be seamlessly integrated with almost everything we do and use.

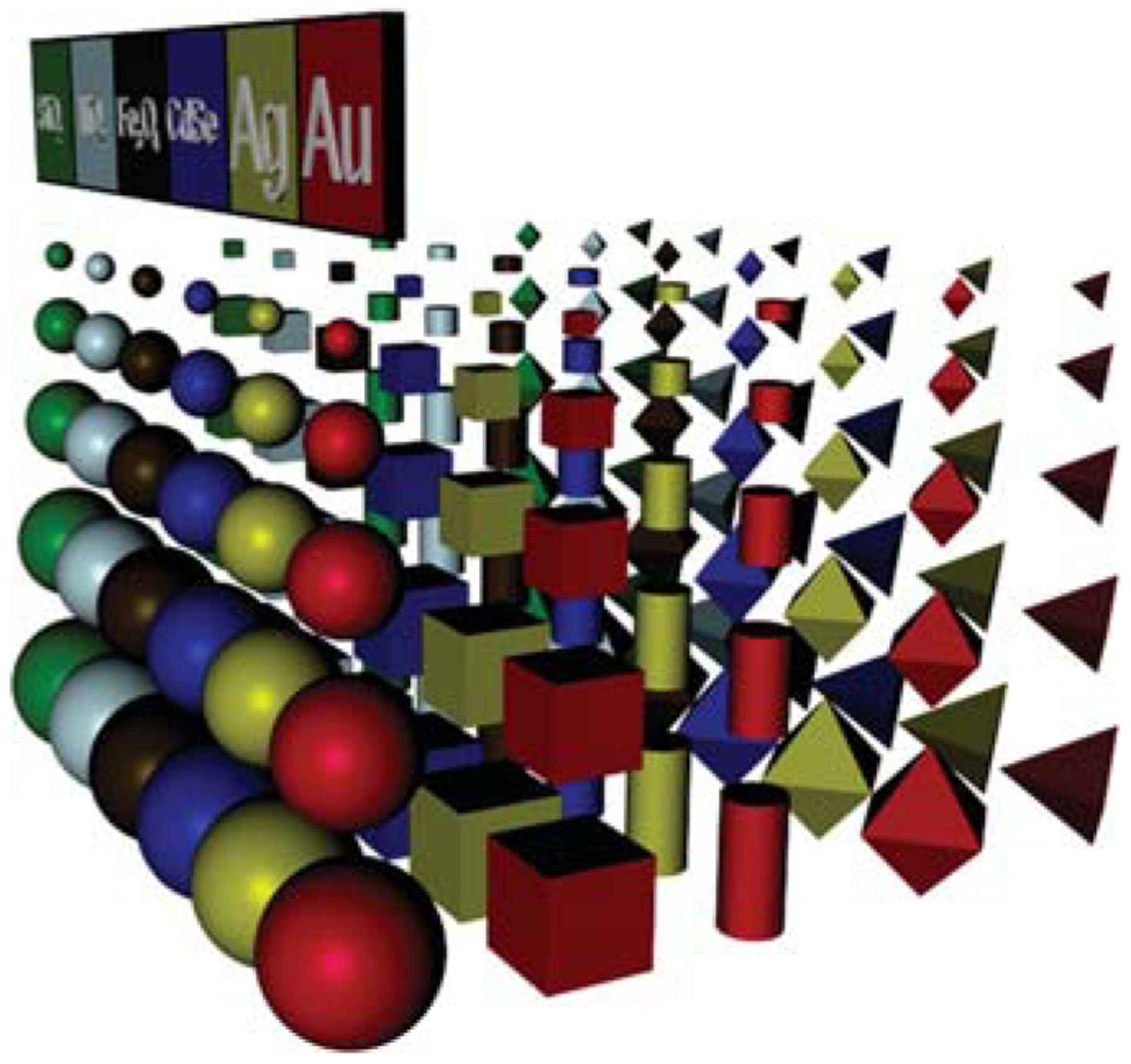

From a fundamental standpoint, there are three general grand challenges in the field of nanoscience and nanotechnology. The first involves the development of tools for miniaturizing bulk materials and creating nanoscale building blocks with control over particle composition, size, shape, and surface functionality7–11 (Figure 1). Indeed, if one analogizes nanotechnology to the well-established field of chemistry, our atoms are nanoparticles, and our periodic table is much more complex because each nanoparticle “element” is not just defined by composition, but also by size, shape, and surface functionalization.

Figure 1.

A portion of the multidimensional nanotechnology periodic table. Entries are defined by the composition, size, shape, and surface functionality (not shown) of each particle.

The second grand challenge involves the development of methods for the hierarchical assembly of nanoscale building blocks into periodic materials.12–18 Essentially, as a community, we need to develop methods to reliably and predictably bond particles to one another in such a way that we can build a macroscopic material from the bottom up. Extending the analogy, clusters of a small number of particles become our molecules, and colloidal crystals are our solid-state atomic and molecular materials analogues. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are beautiful examples of highly ordered, crystalline structures that chemists can construct from atomic and small-molecule building blocks with designed porosity and therefore desirable catalytic and small-molecule sorption properties.19,62 If we consider the change in scale in transitioning from an atom to a 10 nm nanoparticle node to build the equivalent of a MOF from particles, our interconnecting molecules (bonding interconnects) must scale proportionately and be many tens of nanometers long. This significantly limits the number of options for such interconnects, especially when molecular recognition is desired, as a large library of interconnects must be synthesized to achieve diversity in assembled structures. Creating such a set of molecules would be prohibitively time-consuming without an automated synthetic procedure.

The third challenge pertains to determining the consequences involved in the miniaturization of bulk materials and their implications for developing functional devices.1–3,5–7 While the aforementioned versatility of nanomaterials affords a great variety of potential applications, we are still in the infancy of utilizing these structures to create the next generation of technologies that improve both the quality of scientific research across multiple disciplines and the quality of our everyday lives. Indeed, this challenge is of the utmost importance to us as researchers, since it provides a rationale for studying these novel nanoscale phenomena and allows for new, collaborative, multidisciplinary research endeavors that heighten the quality and scope of our scientific community as a whole.

To address these three challenges, in 1996 we introduced the idea of using oligonucleotides as synthetically programmable constructs for guiding the assembly of nanoparticles densely functionalized with DNA, or so-called polyvalent DNA nanoparticle conjugates, into macroscopic materials.13 In principle, with this approach, one could literally program the placement of nanoscale building blocks throughout a three-dimensional material with extraordinary precision. In practice, before such capabilities could be realized, methods for reliably functionalizing the nanoparticles with appropriate sequences of DNA would have to be developed, the fundamental properties of DNA-nanoparticle conjugates would need to be elucidated, and methods for site-specifically functionalizing anisotropic nanoparticles would need to be invented.

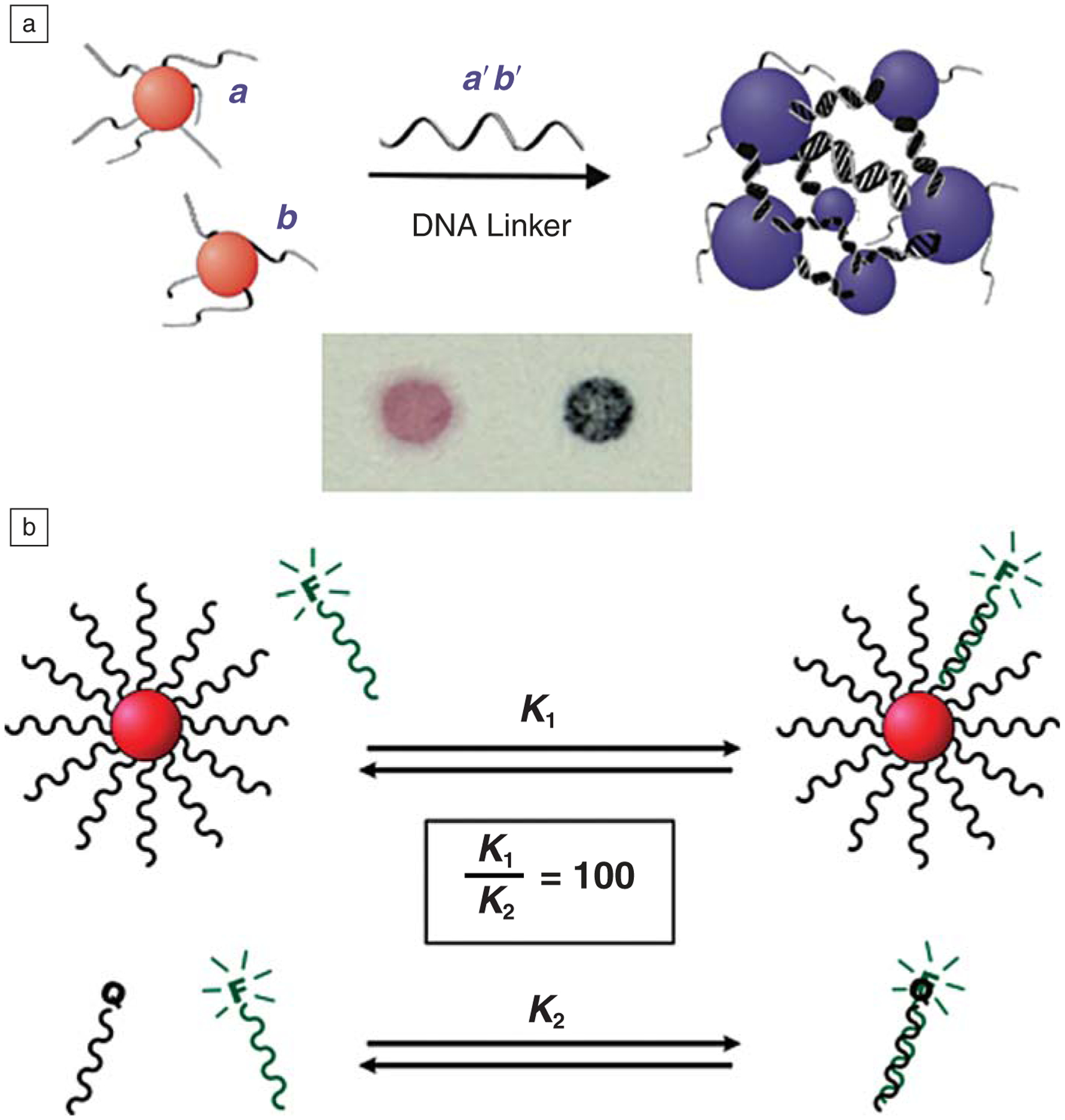

These challenges began a 15-year research odyssey to master the chemical synthesis of these materials and to evaluate the proposition that such a simple approach to materials synthesis could provide the materials design capabilities originally conceptualized. Over the course of that journey, we discovered that these structures have many properties that are unique to the conjugates (Figure 2) and beneficial in many areas, including the fields of biology, medicine, and materials science (Figure 3).1 Today, I plan to describe some of the more compelling discoveries and give you a glimpse of what may follow.

Figure 2.

Polyvalent DNA-nanoparticle bioconjugates exhibit many remarkable properties. (a) By coupling the selective and programmable recognition capabilities of nucleic acids with the surface plasmons of gold nanoparticles (NPs), the DNA-AuNPs can be utilized as probes in highly selective and responsive colorimetric sensors for targets such as DNA, proteins, or small molecules. (b) The dense coating of oligonucleotides on the NP surface results in both high local concentration of DNA strands and high local salt concentration, which results in enhanced binding affinity for complementary DNA targets (top) relative to individual particle-free strands of DNA (bottom). F, fluorophore; Q, quencher.

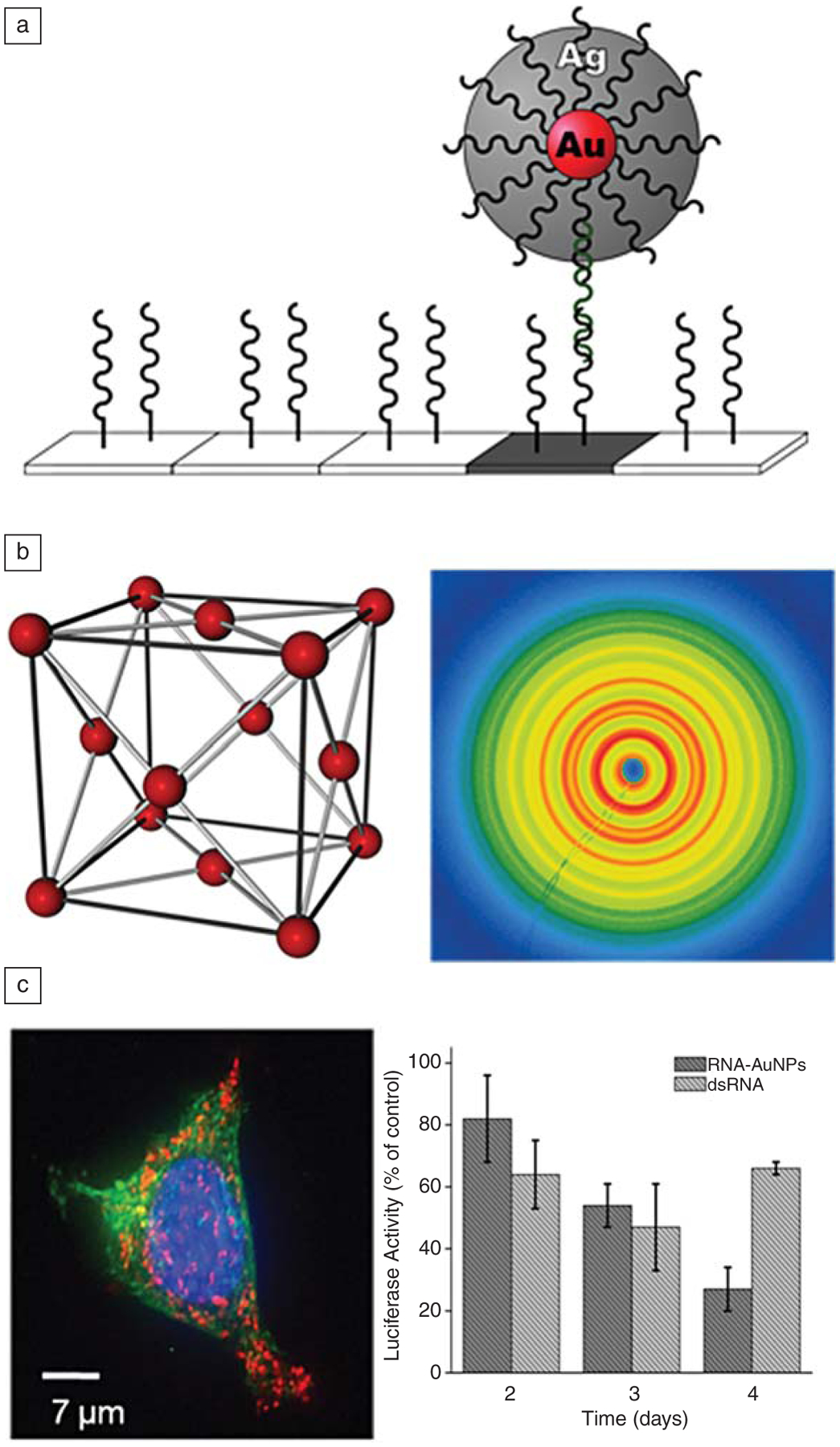

Figure 3.

The unique properties of DNA-nanoparticle conjugates make them useful in a variety of applications. (a) By utilizing the surface of the nanoparticle as a catalyst for the reduction of silver, scanometric detection of analytes is possible with aM detection limits in a sandwich-type assay where single base mismatch selectivity can be obtained. (b) DNA recognition interactions can be used to direct the formation of highly ordered colloidal crystals (left), where the synthetic programmability of the oligonucleotide sequences can be used to control the lattice parameters and crystallographic arrangement of nanoparticles in three dimensions; these crystals can be characterized using synchrotron-based x-ray scattering techniques (right). (c) DNA-functionalized nanoparticles (red fluorescence in the left image comes from a Cy-3 dye attached to the oligonucleotides on the particles) readily enter all cell types tested thus far, making them attractive as intracellular probes and gene-regulating agents. The graph on the right shows the relative knockdown of luciferase, compared to lipofectamine transfected RNA, demonstrating the efficacy of the nucleic acid nanoparticle conjugates for gene regulation. Note that after day four, the effect involving the commercial lipofectin-transfected RNA reverses, while knockdown persists with the polyvalent nanoparticle conjugate.This effect is due to the high intracellular stability of the RNA on the surface of the conjugate, which resists nuclease degradation.

Programmable Colloidal Crystals

Before we could test the idea of programming nanoparticle crystallization with DNA, we had to develop a robust chemistry for functionalizing nanoparticles with nucleic acids. We accomplished this through chemical reaction between citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles and alkylthiol-modified oligonucleotides. A multiday aging procedure, which involved the gradual introduction of oligonucleotides with a simultaneous gradual increase in salt concentration, was used to increase DNA loading and stabilize the conjugates.13 These structures exhibited many interesting and, in certain cases, unexpected and unprecedented properties, some of which made them extremely useful for the development of molecular diagnostic tools. These included hybridization-dependent plasmonic properties,20 cooperative and enhanced binding to complementary particles or free nucleic acid strands,21,22 catalytic properties,23 and shape- and size-dependent light-scattering properties (Figures 2 and 3).24,25 These initial discoveries laid the groundwork for functionalizing well-defined nanostructures with biomolecules for biological detection and extracellular probing processes.23,26,27 Methods developed by our group and others for modifying quantum dots,28 silver particles,29 carbon nanotubes,30 silicon nanowires,31 and many other nanoparticle materials rapidly followed.

Concurrent with this work, the Alivisatos group was developing methods for making monovalent conjugates32 but with a different purpose in mind; they were attempting to create nanoparticle constructs with a single strand of DNA that could be aligned on a second single strand template. This work led to the development of many interesting examples of organized clusters, but such structures are not used for molecular diagnostic purposes and do not exhibit the properties shown in Figure 2, which derive from the dense surface loading of nucleic acids on the surface of the polyvalent conjugate. Today, we can control the average number of oligonucleotides on a particle surface and introduce a variety of additional molecules, such as peptides,33 molecular fluorophores and signaling agents,34 and designer nucleic acids35 as either primary or minority components of the surface ligand shell. This multifunctionality makes these structures extremely useful in many materials synthesis and biomedical applications (see the sections below on bio-diagnostic applications).

To realize crystallization of these conjugates, we had to design constructs that could drive the formation of a specific and desired lattice. We hypothesized that crystallization with the polyvalent conjugates could be facilitated by designing particles with the sequences that would maximize DNA hybridization events for a given target lattice (Figure 4).15 For example, to obtain an fcc lattice, one needs to design a set of particles whose molecular interconnects are self-complementary, where each particle can programmably bind to all other particles. In this case, an fcc crystalline arrangement would provide maximum packing density and therefore maximum DNA hybridization events between particles. However, if one wants to achieve a non-close-packed structure (such as a bcc lattice), two particles with complementary (but not self-complementary) interconnects are needed. Interestingly, this can be accomplished with one particle building block and the appropriate linker molecules. We discovered that the use of flexor entities, consisting of a base not involved in base pairing, created enough conformational flexibility to allow the system to form the desired crystals. Additionally, the crystallization process is facilitated by weak but polyvalent and tailorable interactions between particles, allowing for tuning of optimal DNA-hybridization interactions. When the correct particles are introduced to one another and the temperature of the system is elevated to just below the melting temperature of the duplex DNA interconnects, the weak, polyvalent nature of the DNA interconnects allows for particle reorganization within an aggregate, and well-defined colloidal crystals can be obtained.36 Synchrotron small-angle scattering can be used to verify that the correct structure is formed and assign appropriate lattice constants.

Figure 4.

Utilizing the same DNA-AuNP core, different crystallographic arrangements can be obtained via the addition of different linking DNA strands. Face-centered cubic (fcc) crystals are created via the addition of linkers containing self-complementary recognition sequences, while body-centered cubic (bcc) crystals are created via the addition of linkers containing non-self-complementary recognition sequences that are complementary to each other.

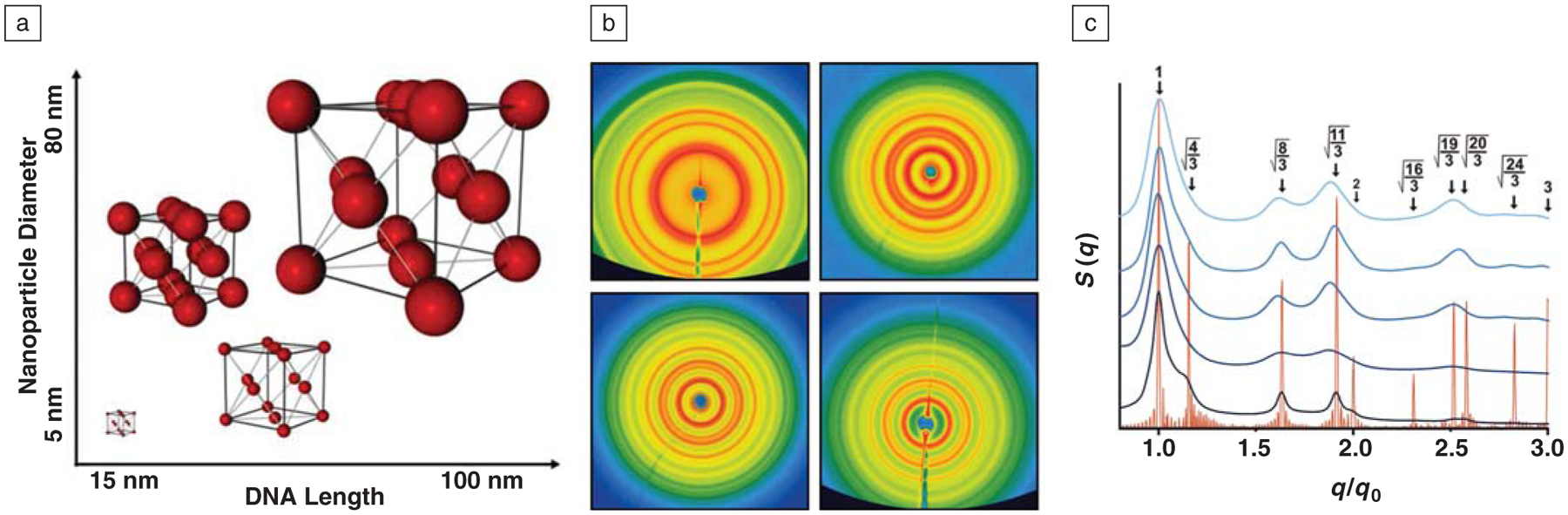

These DNA colloidal crystal networks are an interesting new class of matter. They only exist in solution; if the solvent is removed, the DNA collapses, and the structure is lost. The spacing between the nanoparticles is enormous compared to conventional colloidal crystals and can be tailored over the tens to hundreds of nanometers range simply through the choice of DNA sequence and nanoparticle size (Figure 5).63 Indeed, one of the attractive features of this system is that once one identifies a set of sequences and particles that form a desired structure, one can systematically increase the lattice parameters by keeping the recognition sequences constant and systematically adding spacer blocks of DNA.37 We are not yet sure of the scope of capabilities with this new synthetic approach, but thus far, we15,36,37 and others14,38 have made more than 50 different crystal structures where the structure and lattice parameters were predicted prior to the assembly process. By using conjugates where the particle sizes and shapes are systematically adjusted, one can realize many types of lattices and structures that would be impossible to synthesize any other way. This observation raises the question: can one introduce valency into nanoparticles through face- or edge-selective surface functionalization with different DNA sequences39 to build the equivalent of a coordination geometry in inorganic coordination chemistry? For example, a triangular prism could allow one to create trigonal planar or trigonal bipyramidal coordination environments; a cube could yield an octahedral environment; and a sphere, assymmetrically functionalized on its two hemi-spheres with different DNA, could yield a linear A–B structure. We have begun to develop methods for realizing such structures,39,64,65 and the possibilities for these structures in programmable crystallization, among other areas, are almost limitless.

Figure 5.

(a) DNA can be used to program the formation of colloidal crystals where the lattice parameters can be determined a priori, with variability in both nanoparticle diameter and unit cell edge lengths controllable in the range of tens to hundreds of nanometers. (b) Two-dimensional small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) patterns corresponding to fcc lattices consisting of 10 nm Au nanoparticles with unit cell edge lengths of 40 (top left), 57 (top right), 68 (bottom left), and 77 nm (bottom right). (c) Normalized one-dimensional SAXS patterns from the images in (b) presented with the scattering pattern for a perfect fcc lattice (shown in orange); the fact that all peaks match with the theoretical data demonstrates that all scattering patterns correspond to fcc lattices. In this graph, q is the scattering vector, q0 is the first order scattering peak, and S (q) is the scattering intensity as a function of q.

New Avenues in Molecular Diagnostics Enabled by Polyvalent Nanoparticle Conjugate Materials

The polyvalent nanoparticle conjugate has been used in the development of a wide variety of biodiagnostic assays for the detection of nucleic acids, small molecules, and proteins.40–46 The aforementioned properties have made it possible to develop colorimetric47–49 and light scattering23,24 assays that offer extraordinary sensitivity and selectivity, along with operationally simple readout capabilities when compared to analogous systems based upon molecular probes. The scanometric assay, which involves the use of the conjugate in a sandwich assay format, is now part of the commercialized Verigene* detection system (Figure 6). The scanometric assay utilizes polyvalent conjugates as modalities for selectively recognizing nucleic acid targets captured by a DNA microarray and then amplifying the signal with a subsequent catalytic process that involves the plating of silver from a solution of Ag+ and hydro-quinone.23 In this way, a signal can be increased by a factor as large as 105 in less than five minutes. The results are determined by measuring the scattered light from the developed silver spots with a charge-coupled device camera. The system is quantitative, highly automated, and allows one to detect target concentrations in the high aM to nM range. Since it does not require enzymes, such as polymerase chain reaction, as amplification agents, it is ideal for multiplexing applications. The system is based on our early work at Northwestern University demonstrating both the cooperative binding and catalytic properties of the conjugate. The latter leads to high selectivity assays and the former to high sensitivity ones.

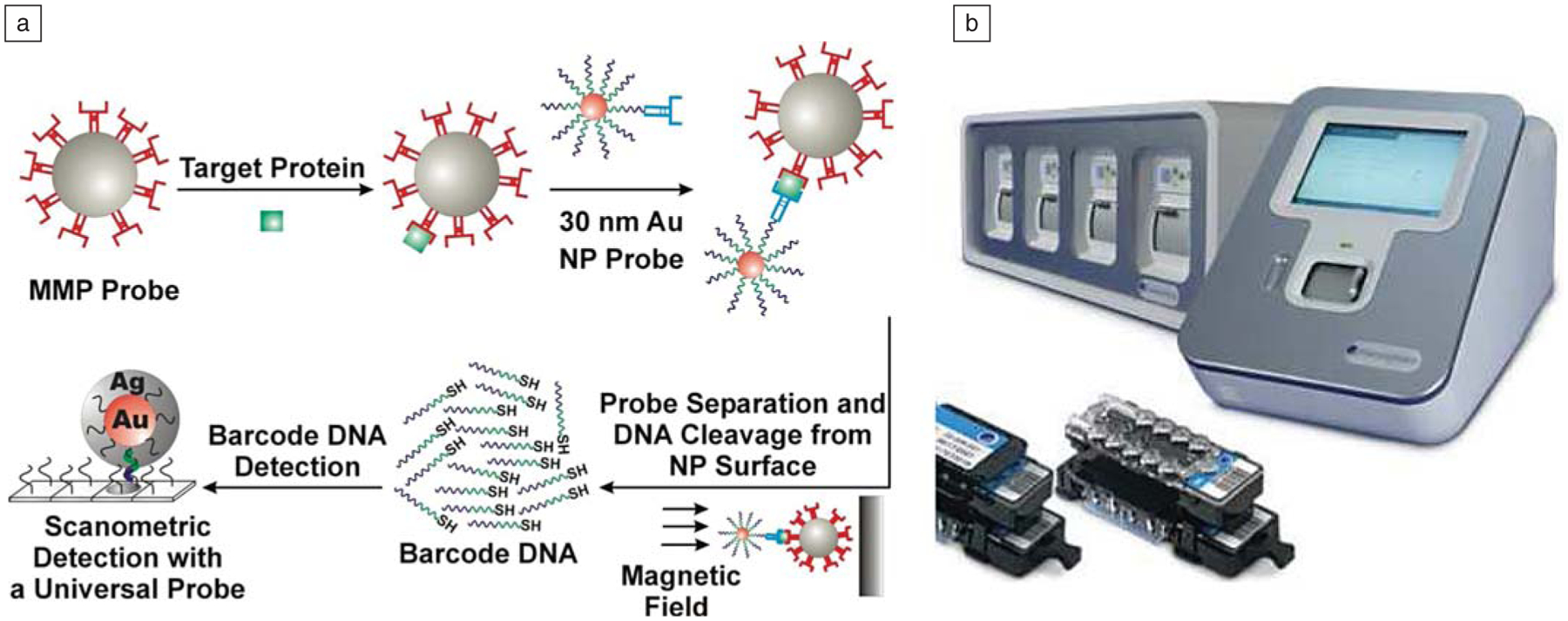

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic diagram of the bio-barcode assay. (b) Verigene System for rapid and sensitive DNA analysis. MMP, magnetic microparticle; NP, nanoparticle.

The Verigene system is now being used to push the frontiers of molecular diagnostics. In addition to providing a rapid way of diagnosing disease based upon genetic markers, we have developed ways of using it to enable high sensitivity protein detection. For example, we have developed the barcode assay, which also relies on a polyvalent nanoparticle conjugate to detect and amplify recognition events involving disease targets.42,43,46,50 The barcode assay utilizes a gold nanoparticle densely functionalized with DNA (called barcode DNA), but it is also modified with antibodies, which can selectively recognize a protein target. In addition to the nanoparticle conjugate, the assay relies on a magnetic microparticle with a second antibody that can sandwich the target of interest. When these two particles encounter a target, for example prostate-specific antigen (PSA), they form a complex that is magnetic and can be isolated from the rest of the solution using a magnetic field.46 Subsequent release of the DNA with a chemical agent that dissolves the particle (e.g., I2) amplifies the initial protein recognition event—each protein captured is traded for hundreds to thousands of DNA strands (depending on particle size). Sorting, identifying, and measuring the concentration of the barcode DNA with the Verigene system translates into an assay that can be orders of magnitude more sensitive than conventional immunoassay technology.

These ultrasensitive capabilities afforded by the polyvalent nanoparticle conjugate are transforming the field of molecular diagnostics and changing the way researchers approach the study of a variety of diseases. Anywhere residual disease or recurrence is an issue, these nanomaterial-based assays play a major role in diagnosis and, ultimately, treatment. For example, we have shown how they can affect the development of prostate and ovarian cancer screening tools that can look at early detection and recurrence, HIV detection systems that can be used to rapidly screen populations for early signs of the disease, and cardiac disease detection systems (based upon Troponin I),51,66 which can identify patients in the early stages of a heart attack before conventional diagnostic methods. They even show promise for tracking Alzheimer’s disease markers, which are at extremely low concentrations in cerebral spinal fluid and blood, and therefore may result in the first clinical molecular diagnostic tools for tracking the disease.43,50 These are great examples of how nanomaterials chemistry and polyvalent nanoparticle conjugates, in particular, not only can provide significant new fundamental insights but also translate into FDA-cleared technology that can positively affect human health.

The Polyvalent DNA Nanoparticle Conjugate and Intracellular Gene Regulation

Gene regulation is an exciting area where the polyvalent DNA-nanoparticle conjugate is having a significant impact. In 2006, Andrew Fire and Craig Mellow were given the Nobel Prize for their contributions to the field of gene silencing. Although the promise of this field is enormous, major barriers toward realizing its benefits in medicine still exist. In particular, we have very few acceptable methods for delivering such agents to cells in an efficient and nontoxic manner. Nucleic acids, because of their negative charge and the negative charge of the cell membrane, do not naturally enter cells in high concentrations without the aid of a transfection material. In addition, when RNA is used as the regulation agent in a small interfering RNA (siRNA) pathway, the inherent instability of the nucleic acid poses a major obstacle for realizing effective and long-lived therapeutics. Traditionally, polymer chemists have designed positively charged polymers that complex with the negatively charged DNA or RNA to help facilitate transfection.52 Although these materials satisfy the transfection problem in certain cases, they often are toxic to the cell or living organism in which they are used.

In 2006, we made a very interesting discovery: polyvalent gold nanoparticle nucleic acid conjugates naturally enter cells without the need of a co-carrier, and hence could be used in both antisense and siRNA gene regulation pathways.33,35,53–55 Since that initial discovery, we have demonstrated that this entry is universal, with more than 50 different cell lines, including primary cells, exhibiting uptake at greater than 99.9% levels. The particles enter via active cellular uptake mechanisms such as endocytosis, and the high-density gold particles, combined with high-resolution electron microscopy, allow one to image them and literally count the number of particles that enter a given cell.56 At the time, this was a counter-intuitive result. Conventional wisdom in the field would have predicted that negatively charged entities such as these DNA-nanoparticle conjugates would never enter a cell based upon simple electrostatic repulsion arguments. Indeed, the cell membrane is negatively charged and does not normally allow negatively charged entities to cross it. However, we have discovered that the particles complex with positively charged trafficking proteins, likely in the cell membrane, and this conjugate-protein complex enters the cell. The ability to bind these proteins correlates with the density of the DNA (or RNA) on the particle surface.56 More proteins bind to a more densely functionalized particle surface, and such complexes exhibit significantly higher uptake.

When the particles are functionalized with oligonucleotides terminated with fluorophores, we can use fluorescence to track where they are in live cells and evaluate their stability. These experiments showed that the oligonucleotides remain chemically attached to the particle once inside the cell, and although they are slowly degraded by nucleases, the rate of degradation is significantly retarded when compared to free DNA.57 This enhanced stability is a major advantage in the context of gene regulation, since it leads to a greater lifetime for the active nucleic acid agent. The origin of this stability is linked to the dense packing of DNA on the nanoparticle surface, which leads to steric limitations with respect to nucleases addressing the nucleic acid strands. In addition, the local environment on the particle surface is very rich in salt, and many enzymes are adversely affected by this environment, which leads to nuclease inhibition and, in this case, slower degradation rates.

The local surface structure of the polyvalent nucleic acid nanoparticle conjugate accounts for many of its distinct properties. In addition to inhibiting nuclease degradation of both DNA and RNA constructs, it also gives the nanoparticles “stealth” capabilities, wherein they enter the cells and perform their desired function but do not trigger negative immune responses that can lead to cell death.58 Polymer carriers will typically trigger the immune response as measured by Interferon-β levels; however, cells treated with polyvalent DNA- or RNA-based nanoparticle conjugates exhibit Interferon-β levels barely above the levels measured in untreated cells when compared to polymer transfection materials carrying the same number of nucleic acids.

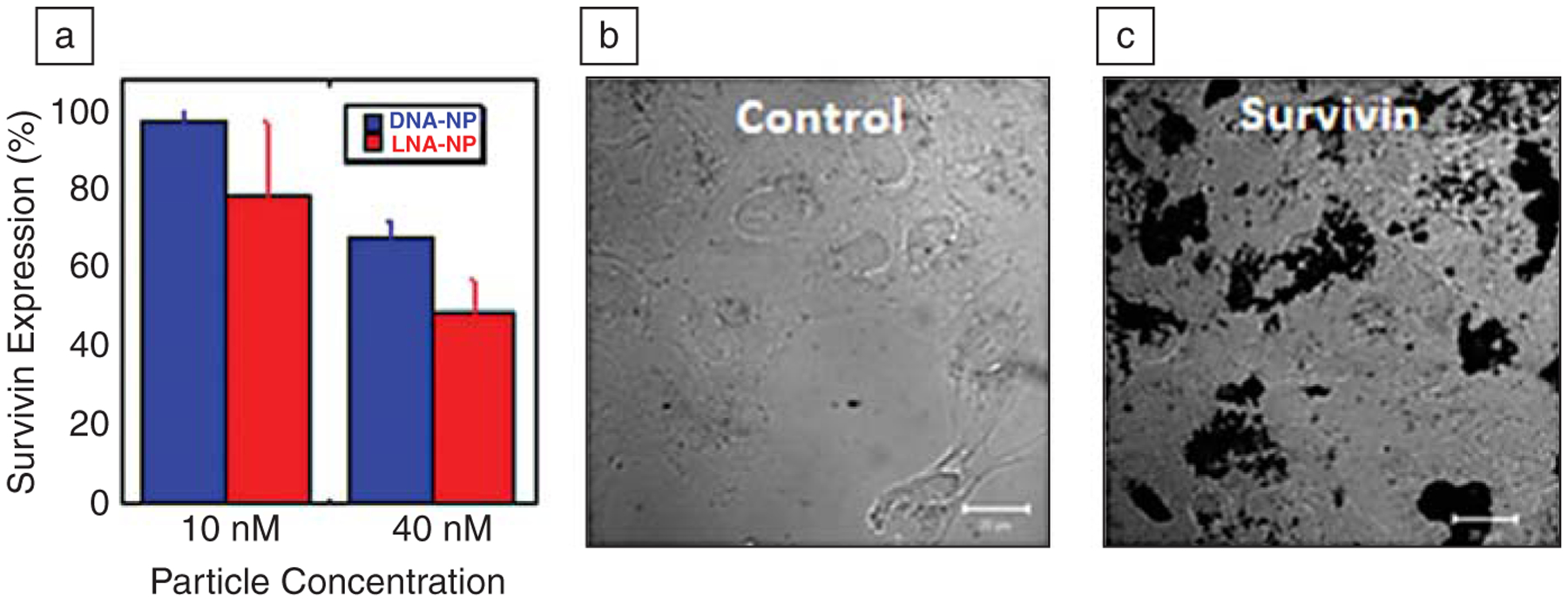

Remarkably, these nanomaterials are extremely effective at knocking down gene expression both in intracellular and animal models. We have begun to study these capabilities in the context of cancer, focusing on the survivin gene. Survivin is a gene responsible for producing proteins that inhibit apoptosis (cell death) and, therefore, lead to cancer cell immortality.35,59 When it is targeted and effectively knocked down, cancer cells die like healthy cells (Figure 7). Here, we have taken advantage of the ability to chemically manipulate the nanoparticle conjugates and introduce designer oligonucleotides such as locked-nucleic acids (LNA). LNA contains an additional bond between the 2’ and 5’ carbons of the ribose sugars in the nucleotides and binds complementary sequences more tightly than DNA. Therefore, we hypothesized that LNA-modified nanoparticles would be more effective at knocking down gene expression than DNA-modified particles in an antisense pathway. Early experiments suggest that this is indeed the case, and there are no apparent side effects. Using lung carcinoma cells, we demonstrated the ability to knock down survivin in a highly sequence-specific manner and to cause subsequent cell death. Cells treated with LNA-modified particles of an incorrect sequence (in fact, a single base mismatch) showed no evidence of knockdown relative to non-targeting control sequences.

Figure 7.

(a) Antisense gold nanoparticles targeted to survivin reduce the levels of survivin protein by up to 50% in lung carcinoma (A549) cells, as measured by western blot, a technique for analyzing protein levels. (b) Cells grow readily when treated with control nanoparticles that do not target any human gene, as shown by light microscopy. (c) However, when the same cells are treated with survivin-targeting nanoparticles, cell death occurs, as illustrated by the buildup of dark masses of cellular debris. In all experiments, nanoparticles were incubated with the cells for four days (40 nM nanoparticle); scale bars are 20 μM.

Combined Diagnostic and Intracellular Gene-Regulation Capabilities in One Nanoparticle Construct

Ideally, one would like to be able to visualize and quantify messenger RNA (mRNA) binding while one is affecting gene knockdown. Such capabilities not only would strengthen the scientific foundation for the observed gene knockdown effects but also could lead to an entire new class of live cell assays, many of which could replace real-time polymerase chain reaction applications. At present, there are no materials that afford this capability.

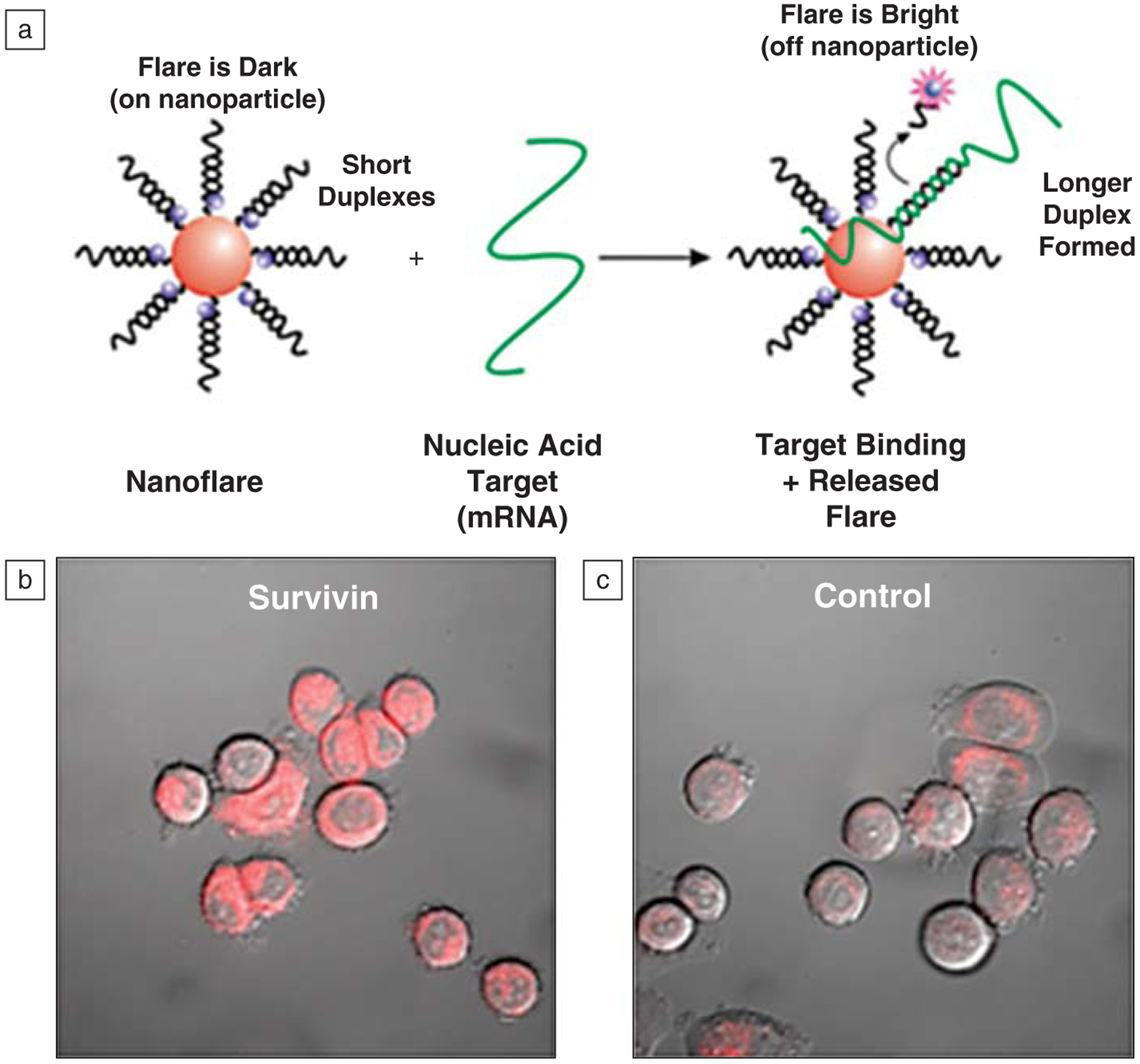

To evaluate such possibilities, we designed and synthesized a new construct called a nanoflare (Figure 8).34,55 This structure is a polyvalent DNA nanoparticle conjugate, but it has a second short oligonucleotide sequence terminated with a fluorophore, which hybridizes with the longer sequence covalently attached to the particle. In the nanoflare construct, the fluorophore, through DNA hybridization, is held close to the fluorescence-quenching gold particle. These structures are spectro-scopically silent, and like the particles without such fluorophores, they naturally enter cells. The floppy portion of the sequence not hybridized with the flare sequence is designed to recognize an mRNA target of interest, for example survivin. Since the strand that is covalently attached to the gold nanoparticle is fully complementary to the target mRNA, the mRNA binding interaction is favored, and it displaces the flare sequence upon binding. This provides a way of quantitatively measuring the concentration of mRNA in a cell while one is affecting knockdown.55 The only other way one could conceive of achieving the same results is through the use of a polymer carrier and the so-called molecular beacons.60 Such structures can be carried into cells, but we find that the nuclease activity leads to enormous background signals and the inability to use this approach effectively in an intracellular assay.

Figure 8.

(a) Schematic diagram of a nanoflare binding to its target mRNA and releasing a fluorophore-labeled flare. (b) Fluorescence confocal microscopy image of human breast cancer (SKBR3) cells treated with survivin-targeting nanoflares. High levels of fluorescence are associated with these cells, consistent with high levels of survivin expression. (c) SKBR3 cells treated with a control nanoflare that does not have a target within the human genome show low associated fluorescence, consistent with background. Nanoparticles were treated with 100 pM nanoflare particles for 24 hours in these experiments.

Since this original discovery, the nanoflare approach has been adapted for other intracellular analytes, such as ATP,61 and it is likely extendable to many others. In addition, the flare can be other signaling agent entities, such as magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents, radioactive entities, and mass spectrometry labels. The advantage of such a construct is that one can create new cell-screening assays, where cell populations are differentiated in real time with cell counting and imaging equipment. These capabilities not only will create new opportunities for studying biological systems but also can be adapted for use in many traditional diagnostics, such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, or conventional x-ray imaging to create a new medical system for real-time patient analysis. In addition, these new detection strategies, combined with the concurrent developments in nanoparticle-based therapeutics, potentially will lead to new opportunities in medicine, including cancer treatments that can be tailored to a specific expression pattern, control of cellular behavior in organ transplants, and the ability to address major problems in infectious diseases, such as bacterial antibiotic resistance and genomic incorporation of viruses.

Conclusion

The polyvalent nucleic acid gold nanoparticle conjugate represents a new and versatile synthon in materials chemistry. It combines the programmable recognition capabilities of nucleic acids with the surface plasmons of gold nanoparticles to yield polyvalent structures with unusual properties that have been exploited extensively in chemistry, biology, medicine, and materials science. These materials are now part of FDA-cleared molecular diagnostic systems, are the basis for intracellular assays, and show promise as a new class of gene regulation agents. In addition, they are the foundation for novel materials synthesis and crystal engineering approaches. In the years to follow, they likely will be developed as a new line of therapeutics for many types of diseases with a genetic basis, including many forms of cancer, and used to construct three-dimensional structures where lattice control provides the ability to exquisitely tailor plasmonic, catalytic, mechanical, and electronic properties.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Kavli Foundation for their generosity in sponsoring this lectureship, MRS, and the many scientists who have contributed to the development of this new field of research. In particular, many of my colleagues at Northwestern University, including George Schatz, Robert Letsinger, Mark Ratner, Amy Paller, and Thomas Meade, have made significant contributions at various project stages. Finally, I thank the National Cancer Institute CCNE Program, NSF, and AFOSR for generous grant support. Robert Macfarlane and Andrew Prigodich are acknowledged for help in preparing this transcript.

This article is based on the Fred Kavli Distinguished Lectureship in Nanoscience presentation given by Chad A. Mirkin (Northwestern University) on November 29, 2009 at the Materials Research Society Fall Meeting in Boston, MA. The Kavli Foundation supports scientific research, honors scientific achievement, and promotes public understanding of scientists and their work. Its particular focuses are astrophysics, nanoscience, and neuroscience.

Biography

Chad A. Mirkin is the director of the International Institute for Nanotechnology, the George B. Rathmann Professor of Chemistry, a professor of chemical and biological engineering, a professor of biomedical engineering, a professor of materials science and engineering, and a professor of medicine at Northwestern University. Mirkin is a chemist and a world-renowned nanoscience expert who is known for his development of nanoparticle-based biodetection schemes, the invention of Dip-Pen Nanolithography, and contributions to supramolecular chemistry. He is the author of more than 400 manuscripts and more than 360 patents and applications and the founder of three companies—Nanosphere, NanoInk, and AuraSense, which are commercializing nanotechnology applications in the life science and semiconductor industries. Mirkin has won more than 60 national and international awards and is a member of the National Academy of Science and the National Academy of Engineering. Mirkin can be contacted via e-mail at chadnano@northwestern.edu.

Footnotes

Note that the author is the founder and stockholder of the company, Nanosphere, which commercialized the Verigene.

References

- 1.Rosi NL, Mirkin CA, Chem. Rev 105, 1547 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell AT, Science 299, 1688 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniel M-C, Astruc D, Chem. Rev 104, 293 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozbay E, Science 311, 189 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talapin DV, Lee J-S, Kovalenko MV, Shevchenko EV, Chem. Rev 110, 389 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baughman RH, Zakhidov AA, de Heer WA, Science 297, 787 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray CB, Kagan CR, Bawendi MG, Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci 30, 545 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao AR, Habas S, Yang PD, Small 4, 310 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin R, Charles Cao Y, Hao E, Metraux GS, Schatz GC, Mirkin CA, Nature 425, 487 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grzelczak M, Perez-Juste J, Mulvaney P, Liz-Marzan LM, Chem. Soc. Rev 37, 1783 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin LD, Park S, Huang L, Mirkin CA, Science 309, 113 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalsin AM, Fialkowski M, Paszewski M, Smoukov SK, Bishop KJM, Grzybowski BA, Science 312, 420 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL, Mucic RC, Storhoff JJ, Nature 382, 607 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nykypanchuk D, Maye MM, van der Lelie D, Gang O, Nature 451, 549 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park SY, Lytton-Jean AKR, Lee B, Weigand S, Schatz GC, Mirkin CA, Nature 451, 553 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shevchenko EV, Talapin DV, Kotov NA, O’Brien S, Murray CB, Nature 439, 55 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redl FX, Cho KS, Murray CB, O’Brien S, Nature 423, 968 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leunissen ME, Christova CG, Hynninen A-P, Royall CP, Campbell AI, Imhof A, Dijkstra M, van Roij R, van Blaaderen A, Nature 437, 235 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Férey G, Chem. Soc. Rev 37, 191 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Storhoff JJ, Lazarides AA, Mucic RC, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL, Schatz GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 122, 4640 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin RC, Wu GS, Li Z, Mirkin CA, Schatz GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 125, 1643 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lytton-Jean AKR, Mirkin CA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 127, 12754 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taton TA, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL, Science 289, 1757 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taton TA, Lu G, Mirkin CA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 123, 5164 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin R, Cao Y, Mirkin CA, Kelly KL, Schatz GC, Zheng JG, Science 294, 1901 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elghanian R, Storhoff JJ, Mucic RC, Letsinger RL, Mirkin CA, Science 277, 1078 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park SJ, Taton TA, Mirkin CA, Science 295, 1503 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell GP, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL, J. Am. Chem. Soc 121, 8122 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J-S, Lytton-Jean AKR, Hurst SJ, Mirkin CA, Nano Lett. 7, 2112 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu YR, Bangsaruntip S, Wang XR, Zhang L, Nishi Y, Dai HJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 128, 3518 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng G, Qin L, Mirkin CA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 47, 1938 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alivisatos AP, Johnsson KP, Peng XG, Wilson TE, Loweth CJ, Bruchez MP, Schultz PG, Nature 382, 609 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel PC, Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Mirkin CA, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 105, 17222 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Hill HD, Prigodich AE, Mirkin CA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 129, 15477 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Rosi NL, Mirkin CA, Chembiochem 8, 1230 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macfarlane RJ, Lee B, Hill HD, Senesi AJ, Seifert S, Mirkin CA, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 106, 10493 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hill HD, Macfarlane RJ, Senesi AJ, Lee B, Park SY, Mirkin CA, Nano Lett. 8, 2341 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng W, Hartman MR, Smilgies D-M, Long R, Campolongo MJ, Li R, Sekar K, Hui C-Y, Luo D, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 49, 380 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millstone JE, Georganopoulou DG, Xu X, Wei W, Li S, Mirkin CA, Small 4, 2176 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thaxton CS, Hill HD, Georganopoulou DG, Stoeva SI, Mirkin CA, Anal. Chem 77, 8174 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoeva SI, Lee JS, Thaxton CS, Mirkin CA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 45, 3303 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nam JM, Thaxton CS, Mirkin CA, Science 301, 1884 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Georganopoulou DG, Chang L, Nam JM, Thaxton CS, Mufson EJ, Klein WL, Mirkin CA, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102, 2273 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thaxton CS, Georganopoulou DG, Mirkin CA, Clin. Chim. Acta 363, 120 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaikh KA, Ryu KS, Goluch ED, Nam JM, Liu JW, Thaxton S, Chiesl TN, Barron AE, Lu Y, Mirkin CA, Liu C, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102, 9745 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thaxton CS, Elghanian R, Thomas AD, Stoeva SI, Lee JS, Smith ND, Schaeffer AJ, Klocker H, Horninger W, Bartsch G, Mirkin CA, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 106, 18437 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daniel WL, Han MS, Lee JS, Mirkin CA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 6362 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JS, Han MS, Mirkin CA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 46, 4093 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JS, Ulmann PA, Han MS, Mirkin CA, Nano Lett. 8, 529 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim EY, Stanton J, Korber BTM, Krebs K, Bogdan D, Kunstman K, Wu S, Phair JP, Mirkin C, Wolinsky SM, Nanomedicine 3, 293 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murakami MM, Apple FS, Hollander JE, Shipp GW, Clin. Chem 55, A64 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lv HT, Zhang SB, Wang B, Cui SH, Yan J, J. Controlled Release 114, 100 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosi NL, Giljohann DA, Thaxton CS, Lytton-Jean AKR, Han MS, Mirkin CA, Science 312, 1027 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Prigodich AE, Patel PC, Mirkin CA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 2072 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prigodich AE, Seferos DS, Massich MD, Giljohann DA, Lane BC, Mirkin CA, ACS Nano 3, 2147 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Patel PC, Millstone JE, Rosi NL, Mirkin CA, Nano Lett. 7, 3818 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seferos DS, Prigodich AE, Giljohann DA, Patel PC, Mirkin CA, Nano Lett. 9, 308 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Massich MD, Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Ludlow LE, Horvath CM, Mirkin CA, Mol. Pharmaceutics 6, 1934 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryan BM, O’Donovan N, Duffy MJ, Cancer Treat. Rev 35, 553 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang KM, Tang ZW, Yang CYJ, Kim YM, Fang XH, Li W, Wu YR, Medley CD, Cao Z, Li J, Colon P, Lin H, Tan W, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 48, 856 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng D, Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Patel PC, Mirkin CA, Nano Lett. 9, 3258 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yaghi OM, O’Keeffe M, Ockwig NW, Chae HK, Eddaoudi M, Kim J, Nature 423, 705 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Macfarlane RJ, Jones MR, Senesi AJ, Young KY, Lee B, Mirkin CA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 49, 4589 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu X-Y, Rosi NL, Wang Y, Huo F, Mirkin CA, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 128, 9286 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huo F, Lytton-Jean AKR, Mirkin CA, Adv. Mater 18, 2304 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thaxton CS, Elghanian R, Thomas AD, Stoeva SI, Lee J-S, Smith ND, Schaeffer AJ,Klocker H, Horninger W, Bartsch G, Mirkin CA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 2010, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]