Abstract

The reinforcer pathologies model of addiction posits that two characteristic patterns of operant behavior characterize addiction. Specifically, individuals suffering from addiction have elevated levels of behavioral economic demand for their substances of abuse and have an elevated tendency to devalue delayed rewards (reflected in high delay discounting rates). Prior research has demonstrated that these behavioral economic markers are significant predictors of many of college students’ alcohol-related problems. Delay discounting, however, is a complex behavioral performance likely undergirded by multiple behavioral processes. Emerging analytical approaches have isolated the role of participants’ sensitivity to changes in reinforcer magnitude and changes in reinforcer delay. The current study uses these analytic approaches to compare participants’ discounting of money versus alcohol, and to build regression models that leverage these new insights to predict a wider range of college students’ alcohol related problems. Using these techniques, we were able to 1) demonstrate that individuals differed in their sensitivity to magnitudes of alcohol versus money, but not sensitivity to delays to those commodities and 2) that we could use our behavioral economic measures to predict a range of students’ alcohol related problems.

Keywords: behavioral economics, reinforcer pathologies, demand, delay discounting, alcohol, multilevel modeling, choice, college students

The reinforcer pathology model posits that substance abuse is the result of an interaction between the excessive valuation of an abused substance and the excessive preference for immediate rewards (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, et al., 2011; Bickel, Johnson, et al., 2014; Jarmolowicz et al., 2016). Toward this end, excessive valuation of abused substances is often measured using demand analyses (Hursh et al., 1988; Hursh & Silberberg, 2008) that assess how individuals defend consumption (i.e., value) of substances of abuse through reports of hypothetical consumption of a commodity across various prices (Jacobs & Bickel, 1999; MacKillop & Murphy, 2006). Excessive preference for immediate rewards is reflected in high delay discounting rates, assessed via decision making tasks wherein individuals make hypothetical choices preferring smaller, sooner reward over later, larger ones (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Koffarnus, & Gatchalian, 2012). These two characteristics of reinforcer pathology are thought to be the etiological markers in the development of substance use disorders (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, et al., 2011), and can both predict the development and maintenance of substance use (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009), and the success of substance use disorder (SUD) treatments (Bickel, Koffarnus et al., 2014; Sheffer et al., 2014; Sheffer et al., 2012; Stanger et al., 2011; Washio et al., 2011). Unfortunately, few studies have concurrently looked these two aspects of reinforcer pathology (Acuff et al., 2018; Aston et al., 2016; Lemley et al., 2016; Sze et al., 2017; Weidberg et al., 2019). Moreover, the few studies that have looked at the interactive propensity of delay discounting rates and behavioral economic demand measures to predict specific addiction indices have generally failed to find a convincing interaction (e.g., Acuff et al., 2018; Lemley et al., 2016). Instead, it appears that discounting and demand metrics predict differing patterns of impairment—which interactively contribute to the behavioral patterns that we call addiction. Given this state of the science, further specification of the behavioral processes that contribute to reinforcer pathology may lead to a greater ability to predict the component behavioral problems that arise in addiction.

Demand assessments allow researchers to see the extent to which individuals are sensitive to changes in price, and therefore the level of resources allocated to obtaining a substance of abuse (Aston & Cassidy, 2019; Bickel, Koffarnus, et al., 2014). The Alcohol Purchase Task (APT) is a reliable measure used to assess individuals’ cost–benefit valuation of alcohol (Kaplan et al., 2018; MacKillop & Murphy, 2006; Murphy et al., 2009). Furthermore, previous research has demonstrated high correspondence between hypothetical and actual alcohol consumption with the APT (Amlung et al., 2012). Demand indices used to evaluate the valuation of alcohol are Q0 (maximum consumption when the commodity is free), Pmax (the price at which responding reaches its maximum value), Omax (peak response output), alpha (change in elasticity), and break point (price at which consumption is driven to zero). These behavioral economic indices are preferred measures as they are sensitive to situational variables (Acuff et al., 2019), such as next day commitments (Gentile et al., 2012), and distal variables such as family history (Murphy et al., 2014). MacKillop and Murphy (2007) investigated the relation between demand for alcohol and alcohol use, where they found that participants who reported greater maximum expenditure for alcohol at baseline reported greater weekly drinking at follow-up (MacKillop & Murphy, 2007). Similarly, MacKillop, Miranda, Monti, Ray, Murphy, Rohesnow, et al. (2010) found that demand for alcohol was significantly associated with symptoms of Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD), but not with quantitative measures of alcohol use (MacKillop, Miranda, Monti, Ray, Murphy, Rohsenow, et al., 2010). Recent meta-analytic findings corroborate these findings, specifically highlighting the robust relation between Q0 and Omax and substance-related outcomes (Zvorsky et al., 2019).

Delay discounting has been extensively used to examine individuals’ preferences between smaller, immediate rewards and larger, delayed rewards. Early research looking at delay discounting investigated differences in discounting rates between those who abused drugs and healthy controls (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Koffarnus, & Gatchalian, 2012; MacKillop et al., 2011). For example, Madden et al. (1997) found that opioiddependent individuals discounted delayed monetary rewards significantly more than the non-drug-using controls. These differences in discounting between those who abuse drugs and healthy controls have been demonstrated with cocaine users (Coffey et al., 2003; Kirby & Petry, 2004), cigarette smokers (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Franck, et al., 2012; Bickel et al., 1999; Mitchell, 1999), obese individuals (Bickel, Wilson, et al., 2014; Jarmolowicz, Cherry, et al., 2014; Rasmussen et al., 2010), and methamphetamine users (Monterosso et al., 2007).

The relations between delay discounting rate and alcohol use, however, have been less consistent. For example, Petry (2001) demonstrated differences in discounting between current alcohol users, abstinent alcohol users, and healthy controls, where she found that alcohol users discounted significantly more than abstinent users and healthy controls. These findings are consistent with those of Vuchinich and Simpson (1998), who found that both social drinkers and problem drinkers discounted delayed money at higher rates than did healthy controls. The dichotomous groups used in these initial studies, however, may have inflated the effect sizes obtained. Other studies, however, have failed to demonstrate these differences (Acuff & Murphy, 2017; Acuff et al., 2018; Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011; Dennhardt et al., 2015; Field et al., 2007; Kirby & Petry, 2004; Luehring-Jones et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2005; Teeters & Murphy, 2015). Notably, Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Franck, et al. (2012) found higher rates of delay discounting in a large sample of hazardous to harmful drinkers, relative to healthy controls—yet those differences were no longer evident once the influence of smoking status was accounted for as a covariate.

Delay discounting rates also often differ based on the commodity presented. For example, Bickel and colleagues (2011b) investigated differences in discounting between cocaine and money among chronic cocaine users, where they found that individuals discounted cocaine significantly more than money. Relatedly, Moody et al. (2017) found that heavy alcohol users discounted alcohol more steeply than money. What these studies show is that individuals discount their preferred substance of abuse at steeper rates than other commodities. For example, Lawyer and Schoepflin (2013) showed that discounting of sex was a better predictor of sexual risk behaviors than was discounting of money. Similarly, Rasmussen et al. (2010) found that percent body fat was a significant predictor of discounting patterns for food. These commodity differences between discounting rates may be notable because discounting of a specific commodity may be uniquely relevant to clinical measures related to that commodity; a concept referred to as domain specificity. However, there are other processes involved which could be influencing choice behaviors.

Reward magnitude and reward delay are two factors thought to independently influence choice behavior. Although one individual may have a strong preference for immediate rewards, another individual may make choices based on the magnitude of the reward. Recently, Young (2017, 2018) suggested using a multilevel logistic regression to evaluate differences in sensitivity to reward magnitude and delay. This approach uses maximum likelihood estimation, rather than error minimization, which allows it to handle missing values and design imbalances more effectively. Furthermore, multilevel logistic regression estimates a model’s parameters at multiple levels simultaneously: the individual and group. This results in estimates being driven less by extreme values and inconsistent data.

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate differences in college students’ discounting of money versus alcohol, using emerging analytic techniques based on maximum likelihood estimation to pinpoint differences in their sensitivities to reward magnitude and delay to each of these commodities. Additionally, the current study evaluated relations between behavioral economic measures (i.e., discounting and demand) and clinical outcomes on the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ), testing the potential of the reinforcer pathologies model to predict alcohol-related problems.

Method

Participants

Fifty-six college students from a large midwestern university served as participants in the current study. A majority of participants were Caucasian (69.6%) women (77%), with an average age of 21 (SD = 1.6; See Table 1 for details). Participants were compensated via extra credit towards their final grade in the course from which they were recruited. All students in the classes from which the sample was recruited were eligible to participate, and no exclusions were made based on demographic factors.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Age, Mean (SD) | 20.88 (1.59) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 43 (77.59) | |

| Male | 43 (21.41) | |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 39 (69.64) | |

| African American | 6 (10.34) | |

| Latino | 6 (10.34) | |

| Asian | 3 (5.36) | |

| American Indian | 1 (1.79) | |

| Multi | 1 (1.79) | |

| Grade Point Average (SD) | 3.16 (0.60) | |

| Monthly Income (SD) | $385 ($444) | |

Setting and Apparatus

Participants completed all experimental-related tasks in a laboratory room at one of four corrals (.91 m x 1.22 m) separated from neighboring workstations by dividers and blocked from the research assistants view by curtains. Each workstation featured a desktop computer, monitor, mouse, and keyboard. Experimental contingencies and data collection were managed by a program written in Microsoft Visual Studio 2013. Responses were made using the computer mouse for all tasks.

General Procedures

All procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board. After reading an information statement, participants completed a brief demographics questionnaire presented on a computer screen. Following completion of the demographics questionnaire, participants completed discounting tasks for both money and alcohol, followed by an assessment of behavioral economic demand and additional tasks/questionnaire measures (available upon request). The order of the delay discounting tasks was counterbalanced across participants.

Questionnaires

Daily Drinking Questionnaire.

Drinking was assessed using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985), which asks questions about the number of drinks consumed in a typical week, as well as the number of drinks consumed in a heavy drinking week.

Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire.

Negative drinking outcomes were assessed using the YAACQ (Read et al., 2006), which is composed of 48 items and assesses negative drinking outcomes in eight areas: Social/interpersonal, impaired control, self-perception, self-care, risky behavior, academic occupation, physical dependence, and blackout drinking.

Alcohol Purchase Task.

Demand for alcohol was assessed using an alcohol purchase task similar to that used by Murphy and MacKillop (2006), which assesses how participants value alcohol by providing them with a scenario and asking them to report how many alcoholic drinks they would consume at various prices. These purchase task assessments have been found to be both reliable and valid (Acuff & Murphy, 2017; Amlung & MacKillop, 2015; Amlung & MacKillop, 2012; MacKillop, Miranda, Monti, Ray, Murphy, Rohesnow, et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2009). Specifically, in building from the prior study by Lemley et al. (2016), additional prices were added to the sequence (i.e., $15, $20, $25, $30) to assure that all participants’ consumption was driven to zero at a price assessed within the task. Participants in the current study received the following instructions:

Imagine that you and your friends are at a bar from 9 P.M. to 2 A.M. to see a band. The following questions ask how many drinks you would purchase at various prices. The available drinks are standard size beer (12oz), wine (5oz), shots of hard liquor (1.5oz), or mixed drinks with one shot of liquor. Assume that you did not drink alcohol before you went to the bar and will not go out after.

Participants were then asked to respond to the following question: “How many drinks would you have if they were? ” at each of the following prices: free, $0.25, $0.50, $1.00, $1.50, $2.00, $2.50, $3.00, $4.00, $5.00, $6.00, $7.00, $8.00, $9.00, $10.00, $12.00, $15.00, $20.00, $25.00, $30.00. Prices were presented in the preceding order, and the task ended when participants reported they would not purchase alcohol at a given price.

Delay Discounting Task (Money).

Participants completed an adjusting amount delay discounting task (Du et al., 2002) in which they made hypothetical choices between $100 larger, later reward available after six ascending delays; 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, and 5 years, or a smaller, sooner reward available immediately. At the beginning of each delay, the amount of the smaller, sooner reward was $50, but this amount was titrated based on the participant’s choice on the previous trial. If the participant chose the larger, later reward, the value of the smaller, sooner reward increased by 50% of the previous titration value (initially $25), but if the participant chose the smaller, sooner reward, the value of the smaller, sooner reward was reduced by 50% of the previous titration value. After the sixth titration at each delay the value of the smaller, sooner reward was the participant’s indifference point.

Delay Discounting Task (Alcohol).

Following the completion of the discounting task with money, participants were presented with a standard drink conversion sheet, and asked to indicate how many drinks were worth $100. This amount was then used as the larger, later reward for alcohol following six ascending delays: 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, and 5 years. At the beginning of each delay, the amount of the smaller, sooner reward was half that of the larger, later reward. Just as in the discounting task with money, this amount was titrated based on the participant’s choices. That is, if the participant chose the larger, later reward, the value of the smaller, sooner reward increased by 50% of the previous titration value. However, if the participant chose the smaller, sooner reward, the value was reduced by 50% of the previous titration. The value of the smaller, sooner reward after the sixth titration at each delay was used as the participant’s indifference point.

Data Analysis

Prior to conducting additional analyses, our behavioral economic variables were processed using the procedures below.

Delay Discounting: Sensitivity to Reward Magnitude and Delay.

All multilevel modeling and regression analyses were conducted in R, an open-source program used for statistical computing and graphics. Multilevel logistic regression was conducted based on the tutorial by Young (2018) to evaluate regression beta weights associated with relative sensitivity to reward magnitude and delay for each participant. In doing so, the influence of each of these variables is isolated for use in second-level analysis. The relative impact of the ratio of the larger, later and smaller, sooner outcome magnitudes was estimated using the following equation:

which isolates the regression beta weights for differences in reinforcer magnitude (βmagnitude) and reinforcer delay (βdelay) based on the current magnitude of the larger, later (LLmagnitude) and smaller, sooner (SSmagnitude) reinforcers as well as the delay to the larger, later reinforcer (LLdelay).

Delay Discounting Rates.

Although analytic techniques are available for calculating delay discounting rate based on a ratio of beta weights for reinforcer magnitude and reinforcer delay, we chose to independently calculate delay discounting rates based on the tutorial by Young (2017). Thus, delay discounting rates for both money and alcohol were calculated using a multilevel model analysis of the indifference points with the hyperbolic equation by Mazur (1987) with the following formula:

which describes how the value of a given amount of a reinforcer (i.e., $100) decreases as a product of the delay to that reinforcer and the rate at which they discount delayed rewards (k).

Demand.

Demand for alcohol was characterized using observed intensity (i.e., consumption when alcohol was free) and breakpoint (i.e., zthe first price at which no alcohol was purchased). As in several of our prior studies (Higgins et al., 2017; Kaplan et al., 2017), we restricted our analysis of these individuals participant demand curve data to these observed metrics due to challenges deriving meaningful demand curve parameters at the individual level. Data from all participants for whom demand was driven to zero within the prices assessed in the current study were included in our analyses.

Second level analysis.

Our discounting variables (delay discounting rates, Beta weights for sensitivity to changes in magnitude and delay) were then analyzed via paired t-tests and as predictors in stepwise linear regression analyses of the total score on the YAACQ, as well as for each of the YAACQ subscales.

Results

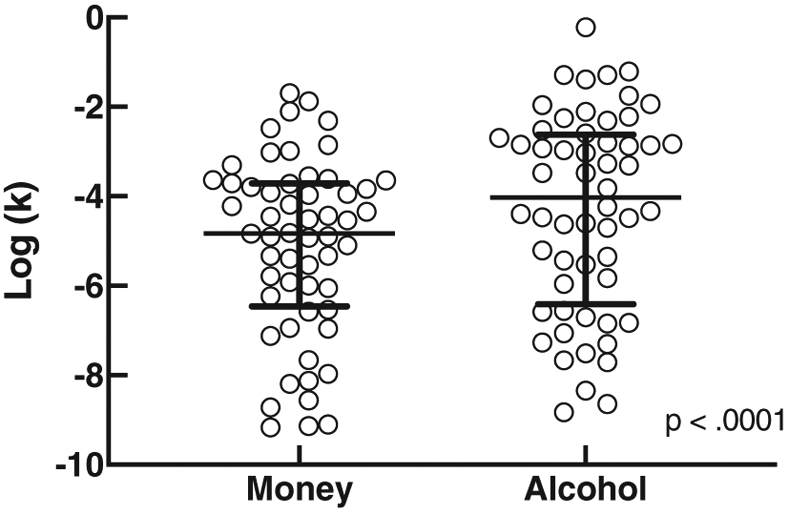

Discounting indifference points for money (M RMSE = 11.1, SD = 11.04) and alcohol (M RMSE = 18.72, SD = 18.68) were well described by Mazur’s (1987) hyperbolic model. Figure 1 shows log(k) values for both the discounting of money and alcohol, where each data point represents an individual participant. A paired t-test found that delay discounting rates were significantly higher for alcohol than money t (55) = 4.65, p < .0001. Figure 2 shows β Magnitude (top panel) and β Delay (bottom panel) regression weights for both money and alcohol. A paired t-test showed a significant difference in sensitivity to reward magnitude between money and alcohol t(55) = 6.877, p <.0001. No significant difference in sensitivity to delay between money and alcohol t(55) = .5264, p = .6 was obtained. Participants’ alcohol demand intensity (Q0; median = 8, IQR = 5, 10) and breakpoint (BP; median = $10, IQR = $8, $18.75) were moderate but variable.

Figure 1.

Log (K) Values for Participants Across Money and Alcohol

Note. Each data point represents an individual participant.

Figure 2.

Regression Weights for Reward Magnitude and Delay for Both Money and Alcohol Are Presented

Note. Each data point represents an individual participant.

Table 2 shows stepwise linear regression models for the YAACQ total and each of the eight subscales. Given considerable demographic homogeneity (Table 1), demographic factors were not included in these models. Behavioral economic measures were significant predictors on the YAACQ total scale and each of the subscales. Alcohol delay discounting rate was a significant predictor of three of the YAACQ subscales (self-perception, self-care, and physiological dependence) whereas money delay discounting rate was not a significant predictor of any subscale. Beta weights from participants’ sensitivity to delay and magnitude on the monetary delay discounting task were, however, significant predictors of both the YAACQ total score and three subscales (impaired control, academic/occupational impairment, and blackout drinking) and beta weights for both magnitude and delay from the discounting of alcohol were a significant predictor of one YAACQ subscale (blackout drinking). Our behavioral economic measure of demand intensity (Q0) was a significant predictor for one YAACQ subscale (interpersonal/occupational impairment) and our measure of demand breakpoint (BP) was a significant predictor of two of the subscales (impaired control and risky behavior).

Table 2.

Stepwise Regression Values for the YAACQ and Its Subcategories

| R2 | p | Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YAACQ Total | 0.11 | 0.012 | βdelay $ | 4.87 | 1.89 | 0.33 | 2.59 | 0.012 |

| Interpersonal | 0.10 | 0.018 | Q0 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 2.43 | 0.018 |

| Impaired Control | 0.28 | 0.001 | βdelay$ | 1.41 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 3.11 | 0.003 |

| BP | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 2.64 | 0.011 | |||

| βmagnitude$ | −0.20 | 0.09 | −0.26 | −2.22 | 0.031 | |||

| Self-Perception | 0.07 | 0.044 | Ln(k)alcohol | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.27 | −2.06 | 0.044 |

| Self-Care | 0.08 | 0.036 | Ln(k)alcohol | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.28 | −2.15 | 0.036 |

| Risky Behavior | 0.08 | 0.033 | BP | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 2.19 | 0.033 |

| Academic | 0.07 | 0.045 | βmagnitude$ | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 2.05 | 0.045 |

| Dependence | 0.12 | 0.009 | Ln(k)alcohol | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.35 | 2.71 | 0.009 |

| Blackout | 0.22 | 0.001 | βmagnitude$ | −0.45 | 0.13 | −0.45 | −3.54 | 0.001 |

| βdelayAlcohol | 1.06 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 2.53 | 0.015 |

Table 3 shows the correlations between our delay discounting measures and our measure of alcohol consumption (DDQ) and related problems (YAACQ). Delay discounting for money was significantly correlated with our other delay discounting measures, particularly participants’ sensitivity to delays to receiving money. A similar pattern was seen for delay discounting of alcohol. By contrast, our measures of behavioral economic demand did not correlate with any of our delay discounting measures.

Table 3.

Correlations Between Behavioral Economic Measures and the YAACQ

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. | 18. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Magnitude of Money | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. | Delay of Money | −.10 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. | Magnitude of Alcohol | .29* | .15 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. | Delay of Alcohol | .29 * | .35 ** | −.10 | |||||||||||||||

| 5. | Log(k) Alcohol | −.25 | −.46 ** | −.34 * | −.69 ** | ||||||||||||||

| 6. | Log(k) Money | −.48 ** | −.74 ** | −.37 ** | −.40 ** | .52 ** | |||||||||||||

| 7. | YAACQ Total | −.25 | .33 * | .13 | .19 | −.28 * | −.25 | ||||||||||||

| 8. | Impaired Control | −.05 | .12 | .15 | .08 | −.18 | −.08 | .65 ** | |||||||||||

| 9. | Social/interpersonal | −.30 * | .33 * | .02 | −.03 | −.05 | −.17 | .50 ** | .25 | ||||||||||

| 10. | Self-Perception | −.01 | .27 * | .07 | .03 | −.27 * | −.23 | .12 | −.27 * | −.04 | |||||||||

| 11. | Self-Care | −.04 | .11 | .20 | .20 | −.28 * | −.12 | .73 ** | .53 ** | .16 | .03 | ||||||||

| 12. | Risky Behavior | −.22 | .02 | −.07 | .03 | .10 | −.03 | .42 ** | −.02 | .09 | .13 | .17 | |||||||

| 13. | Academic/Occupational | −.27* | .08 | .06 | .01 | .05 | −.27 * | −.17 | −.29 * | −.12 | .02 | −.38 ** | −.03 | ||||||

| 14. | Physical Dependence | −.01 | .20 | .15 | .22 | −.35 ** | −.29 | .62 ** | .50 ** | .25 | −.01 | .48 ** | .04 | −.15 | |||||

| 15. | Blackout Drinking | −.36 ** | .23 | −.04 | .19 | .20 | −.02 | .75 ** | .35 ** | .27 * | .10 | .44 ** | .31 * | −.30 * | .34 ** | ||||

| 16. | Q0 | −.20 | −.03 | −.06 | −.18 | .03 | .09 | .16 | .31 * | .13 | −.06 | .06 | .05 | −.02 | .04 | 0 | |||

| 17. | Breakpoint | −.01 | −.23 | −.16 | −.24 | .23 | .07 | .15 | .10 | .24 | −.12 | .15 | .29 * | .01 | −.02 | −.13 | .22 | ||

| 18. | DDQ Typical Week | −.14 | −.06 | .10 | −.10 | −.07 | .11 | .35 ** | .43 ** | .28 * | −.07 | .40 ** | −.06 | −.39 | .25 | .25 | .18 | .13 | |

| 19. | DDQ Heavy Week | −.25 | .07 | .05 | −.07 | −.06 | .12 | .35 ** | .53 ** | .09 | −.18 | .42 ** | .09 | −.39 ** | .16. | .27 * | .21 | .03 | .71 |

Note. Significant relations are indicated by bold font.

= .05 level

= .001 level.

Discussion

Consistent with the reinforcer pathologies model (Bickel & Athamneh, 2020; Bickel, Jarmolowicz, MacKillop, et al., 2012; Bickel, Jarmolowicz, et al., 2011; Bickel, Johnson, et al., 2014; Carr et al., 2011; Jarmolowicz et al., 2016), regression models accounting for students’ overvaluation of alcohol and preferences for immediate rewards predicted each subtype of the participants’ alcohol related problems (Lemley et al., 2016). This adds to the growing body of research supporting this theoretical approach (Deshpande et al., 2019; Epstein et al., 2014; Feda et al., 2015; Lemley et al., 2017; Lemley et al., 2016; Rollins et al., 2010). Importantly, although each of the subscales of the YAACQ were predicted by our behavioral economic measures, no single behavioral economic measure predicted all YAACQ subscales, suggesting a combination of behavioral processes may be needed to successfully predict the full range of alcohol-related problems that students experience. There are five additional points we would like to make about these data.

First, consistent with prior studies examining delay discounting rates for money and alcohol, alcohol was discounted at a higher rate than money (Petry, 2001). The current study used an emerging analytical approach to tease apart the component behavioral processes that may drive the elevated rates of discounting alcohol relative to money (Wileyto et al., 2004; Young, 2018). Specifically, the logistic regression model used to process the delay discounting data provided independent analyses of participants’ sensitivity to changes in the amount of alcohol versus money and changes in the delay to alcohol or money. The current findings suggest that participants are less sensitive to changes in the amount of alcohol provided than to changes in the amount of money provided. Thus, the divergent delay discounting rates observed across commodities are likely driven by this differential sensitivity to the magnitude of alcohol relative to sensitivity to changes in the magnitude of money. Given the persistent differences in discounting across commodities, replicating these findings across other substances of abuse wherein this domain effect is observed, such as opioids (Madden et al., 1997), tobacco (Lawyer et al., 2011), and cocaine (Bickel, Landes, et al., 2011) may provide important information about both delay discounting processes and substance use.

Second, the regression weights representing participants’ sensitivity to magnitude and delay to money and/or alcohol delivery provided unique insights upon second level analysis. As noted above, these secondary analyses may provide additional insight into the domain effect. Specifically, commodity differences seem to relate to differential sensitivities to the amounts of these commodities. More interesting, however, is that these regression weights were significant predictors of multiple subscales of alcohol-related problems in subsequent regression analyses—even though delay discounting rates did not contribute to the model. Notably, delay discounting rates for money were not a significant predictor of any alcohol-related problems, whereas beta weights for participants’ sensitivity to delayed money (YAACQ total and impaired control) and different magnitudes of money (impaired control, academic and occupational impairment, and blackout drinking) performed well in our regression analyses. Hence, the current findings build upon prior studies using reinforcer pathologies processes (i.e., delay discounting and behavioral economic demand (Lemley et al., 2017; Lemley et al., 2016; Rollins et al., 2010) by leveraging a more precise quantification of delay discounting processes to predict alcohol-related problems.

Third, the current findings help clarify the role of delay discounting processes in the reinforcer pathologies model. When the reinforcer pathologies model is discussed (Bickel & Athamneh, 2020; Bickel, Jarmolowicz, MacKillop, et al., 2012; Bickel, Jarmolowicz, et al., 2011; Bickel, Johnson, et al., 2014; Carr et al., 2011; Jarmolowicz et al., 2016), excessive rates of delay discounting are consistently implicated. Delay discounting, however, is a complex process assessed by presenting rewards that differ in both their magnitude and relative immediacy. Choice could be driven by participants’ sensitivity to the delay to the receipt of a particular commodity. For example, both Bickel, Landes, et al. (2011) and Jarmolowicz, Landes, et al. (2014) found that elevated rates of delay discounting for cocaine and sex, respectively, were largely driven by participants’ inability to value that reward as it is delayed. In the current analysis, this corresponds to participants’ sensitivity to the delay of a commodity, a significant predictor of many alcohol-related problems (i.e., self-perception, risky behavior, physical dependence). By contrast, delay discounting rates appear to also be driven, in part, by participants’ sensitivity to the magnitude of the discounted commodity—which was also predictive of a number of alcohol-related problems. The take-home message is that, although delay discounting is an important component of the reinforcer pathologies model, this more nuanced analysis may allow for more nuanced statements about alcohol abuse.

Fourth, these findings contribute to the literature on operant demand in a number of ways. For instance, despite well-known links between demand and alcohol-related outcomes, relatively few studies have examined the relation between demand and the YAACQ; this is surprising given the relatively dense literature on alcohol in young adults (Kaplan et al., 2018). The current findings are consistent with findings from some prior studies. As with prior studies, the relations between discounting and demand measures were underwhelming (Amlung et al., 2017; Luehring-Jones et al., 2016), yet relations may have been observed if discounting rate had been used to dichotomize the sample (Lemley et al., 2016). Additionally, our finding that intensity of demand (Q0) was a significant predictor of alcohol-related social/interpersonal problems directly replicates Lemley et al. (2016), in a similar population. Unlike prior studies (Acuff et al., 2018; Amlung & MacKillop, 2015; Dennhardt et al., 2015), however, we were unable to demonstrate a relation between YAACQ total and intensity of demand (cf. Amlung and MacKillop, 2015; Lemley et al., 2016; Murphy et al., 2015). This inconsistency leaves the relation between intensity of demand and YAACQ total score unresolved. Moreover, while Amlung and MacKillop (2015) did not find relations between breakpoint and YAACQ, Lemley et al. (2016) did. A potential explanation is that Amlung and MacKillop used participants reporting a history of heavy-drinking episodes, while our study used participants with a more diverse range of drinking histories (i.e., not limited to participants with heavy-drinking episodes). It is reasonable to assume that the potentially broader range of YAACQ scores could yield a more sensitive account of the relation between breakpoint and drinking problems.

Another contribution of the present study to the demand literature is the direct comparison with delay discounting in accounting for clinically important drinking outcomes. Despite the proliferation of the reinforcement pathologies model of substance use, a relatively small number of studies have directly used both discounting and demand (Aston et al., 2016; Lemley et al., 2016; Sze et al., 2017; Weidberg et al., 2019), especially when considering the differential predictive utility of these behavioral economic measures in accounting for substance use problems. Specifically, we are aware of no previous literature integrating discounting and demand to predict substance use outcomes using multilevel logistic regression. A unique contribution of behavioral economic demand is its multifaceted account of reinforcer valuation. The demand construct is complex and composed of various components and indices. The present findings highlight the unique contributions of Q0 and breakpoint across various dependent measures; that we found various ways these indices significantly related to YAACQ outcomes underscores the importance of the multifaceted construct of demand in the substance use literature (see Murphy et al., 2015).

Lastly, shortcomings of the current study can be addressed by future research. For example, although the current findings are promising, the sample size was somewhat small. As a result, the current study may have been underpowered in its ability to identify multiple significant predictors of many alcohol-related problems (e.g., social/interpersonal, self-perception, YAACQ total). This possibility is suggested by the fact that the significant binomial correlations between each YAACQ and our behavioral economic models were obtained. Moreover, our overall measure of alcohol use, the daily drinking questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985), only provides a rough measure of alcohol use, which may yield differential levels of intoxication across males and females. Although we did not use this measure to categorize students based on drinking levels (which typically takes gender into account), correlational analysis based on this gross measure may have been impacted by these gender differences, even with the sample being predominantly female. While there is not a straightforward way to adjust this raw data to account for the gender differences, this limitation must be acknowledged.

Additionally, the generality of the current findings may be jeopardized by the size of the sample, number of analyses, as well as by the fact that it was exclusively made up of college students. Given the exploratory nature of the current study, and the modest sample size, adjustments for multiple comparisons were not made. While the obtained findings were robust, these adjustments would have provided additional confidence that the findings were not due to type 1 error. Replication of these findings in a larger sample, adjusted for multiple comparisons, would allow for stronger statements to be made. Moreover, universities house large numbers of individuals at a point in neurobiological development that represent a particular risk for substance misuse and/or addiction (Steinberg, 2010). As a result, college students engage in elevated rates of binge drinking (Silveri, 2012; Wechsler et al., 1994) and experience high rates of alcohol-related physical/sexual violence (Ngo, Ait-Daoud, et al., 2018; Wechsler et al., 1994) and/or death (Ngo, Rege, et al., 2018). Nevertheless, despite the current sample representing an important population, the current findings would be strengthened by replicating these findings in a larger, more diverse population. Relatedly, the regression analyses included in the present study did not include demographic variables such as income or smoking status. This omission occurred for three reasons: considerable demographic homogeneity in our obtained sample, remarkably few cigarette smokers, and difficulties accurately determining income in a population with varying degrees of financial independence from their parents.

Lastly, although the multilevel analyses used in the current study present a number of advantages over traditional analyses of behavioral economic data (Young, 2017, 2018), the second level analyses (e.g., t-tests, regression) were still conducted on behavioral economic markers (i.e., delay discounting rates, Beta weights) that differ in their certainty from participant to participant. This is a foundational difficulty with second level analyses of behavioral economic data derived from any model and/or analytic approach, yet one important to consider when interpreting any such data.

References

- Acuff SF, Amlung M, Dennhardt AA, MacKillop J, & Murphy JG (2019). Experimental manipulations of behavioral economic demand for addictive commodities: A meta-analysis. Addiction, 115 (5), 817–831. 10.1111/add.14865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuff SF, & Murphy JG (2017). Further examination of the temporal stability of alcohol demand. Behavioural Processes, 141(1), 33–41. 10.1016/j.beproc.2017.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuff SF, Soltis KE, Dennhardt AA, Berlin SB, & Murphy JG (2018). Evaluating behavioral economic models of heavy drinking among college students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(7), 1304–1314. 10.1111/acer.13774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung M, & MacKillop J (2015). Further evidence of close correspondence for alcohol demand decision making for hypothetical and incentivized rewards. Behavioral Processes, 113, 187–191. 10.1016/j.beproc.2015.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung M, MacKillop J, Monti PM, & Miranda R (2017). Elevated behavioral economic demand for alcohol in a community sample of heavy drinking smokers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(4), 623–628. 10.1528/jsad.2017.78.623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, Acker J, Stojek MK, Murphy JG, & MacKillop J (2012). Is talk "cheap"? An initial investigation of the equivalence of alcohol purchase task performance for hypothetical and actual rewards. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36(4), 716–724. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01656.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, & MacKillop J (2012). Consistency of self-reported alcohol consumption on randomized and sequential alcohol purchase tasks. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 65(3), 1–6. 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston ER, & Cassidy RN (2019). Behavioral economic demand assessments in the addictions. Current Opinion on Psychology, 30, 42–47. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston ER, Metrik J, Amlung M, Kahler CW, & MacKillop J (2016). Interrelationship between marijuana demand and discounting of delayed rewards: Convergence in behavioral economic methods. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 169, 141–147. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Epstein LH, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, & Wileyto EP (2009). Does delay discounting play an etiological role in smoking or is it a consequence of smoking? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 103(3), 99–106. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, & Athamneh LN (2020). A reinforcer pathology perspective on relapse. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 113(1), 48–56. 10.1002/jeab.564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, MacKillop J, Epstein LH, Carr K, Mueller ET, & Waltz T (2012). The behavioral economics of reinforcement pathologies. In Shaffer HJ (Ed.), Addiction syndrome handbook. American Psychological Association. 10.1037/13750-014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Franck CT, Carrin C, & Gatchalian KM (2012). Altruism in time: social temporal discounting differentiates smokers from problem drinkers. Psychopharmacology, 224, 109–120. 10.1007/s00213-012-2745-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, & Gatchalian KM (2011). The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of reinforcer pathologies: Implications for etiology and treatment of addiction. Current Psychiatry Reports, 13(5), 406–415. 10.1007/s11920-011-0215-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus MN, & Gatchalian KM (2012). Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a transdisease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: emerging evidence [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 134(3), 287–297. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, & Murphy JG (2014). The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: Reinforcement pahologies and thier repair. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 641–677. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Koffarnus MN, Moody L, & Wilson AG (2014). The behavioral- and neuro-economic process of temporal discounting: A candidate behavioral marker of addiction. Neuropharmacology, 76 Pt B, 518–527. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jackson L, Jones BA, Kurth-Nelson Z, & Redish AD (2011). Single- and cross-commodity discounting among cocaine addicts: The commodity and its temporal location determine discounting rate. Psychopharmacology, 217(2), 177–187. 10.1007/s00213-011-2272-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, & Madden GJ (1999). Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology, 146(4), 447–454. 10.1007/PL00005490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Wilson GA, Franck CT, Mueller ET, Jarmolowicz DP, Koffarnus MN, & Fede SJ (2014). Using crowdsourcing to compare temporal, social temporal, and probability discounting among obese and non-obese individuals. Appetite, 75, 82–89. 10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr KA, Daniel TO, & Epstein LH (2011). Reinforcement pathology and obsesity. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 4(3), 190–196. 10.2174/1874473711104030190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Gudleski GD, Saladin ME, & Brady KT (2003). Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11(1), 18–25. 10.1037/1064-1297.11.1.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, & Marlatt GA (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 189–200. 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, & Murphy JG (2011). Association between depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems in European Ameircan and African American college students. Psychology of Addictive Behavior, 25(4), 595–604. 10.1037/a0025807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, Yurasek AM, & Murphy JG (2015). Change in delay discounting and substance reward value following a brief alcohol and drug use intervention. Journal of The Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 103(1), 125–140. 10.1002/jeab.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande HU, Mellis AM, Lisinski JM, Stein JS, Koffarnus MN, Paluch RA, Schweser F, Zivadinov R, LaConte SM, Epstein LH, & Bickel WK (2019). Reinforcer pathology: Common neural substrates for delay discounting and snack purchasing in prediabetics. Brain and Cognition, 132, 80–88. 10.1016/j.bandc.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Green L, & Myerson J (2002). Cross-cultural comparisons of discounting delayed and probabilistic rewards. The Psychological Record, 52, 479–492. 10.1007/BF03395199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Jankowiak N, Fletcher KD, Carr KA, Nederkoorn C, Raynor HA, & Finkelstein E (2014). Women who are motivated to eat and discount the future are more obese. Obesity, 22, 1394–1399. 10.1002/oby.20661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feda DM, Roemmich JN, Roberts A, & Epstein LH (2015). Food reinforcement and delay discounting in zBMI-discordant siblings. Appetite, 85 (185–189). 10.1016/j.appet.2014.11.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Christiansen P, Cole J, & Goudie A (2007). Delay discounting and the alcohol Stroop in heavy drinking adolescents. Addiction, 102(4), 579–586. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01743.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile ND, Librizzi EH, & Martinetti MP (2012). Academic constraints on alcohol consumption in college students: a behavioral economic analysis. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20(5), 390–399. 10.1037/a0029665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Sigmon SC, Tidey JW, Gaalema DE, Hughes JR, Stitzer ML, Durand H, Bunn JY, Priest JS, Arger CA, Miller ME, Bergeria CL, Davis DR, Streck JM, Reed DD, Skelly JM, & Tursi L (2017). Addiction potential of cigarettes with reduced nicotine content in populations with psychiatric disorders and other vulnerabilities to tobacco addiction. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(10), 1056–1064. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Raslear TG, Shurtleff D, Bauman R, & Simmons L (1988). A cost-benefit analysis of demand for food. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 50(3), 419–440. 10.1901/jeab.1988.50-419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, & Silberberg A (2008). Economic demand and essential value. Psychological Review, 115(1), 186–198. 10.1037/2008-00265-008 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EA, & Bickel WK (1999). Modeling drug consumption in the clinic via simulation procedures: Demand for heroin and cigarettes in opioiddependent outpatients. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 7(4), 412–426. 10.1037/1064-1297.7.4.412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Cherry JB, Reed DD, Bruce JM, Crespi JM, Lusk JL, & Bruce AS (2014). Robust relation between temporal discounting rates and body mass. Appetite, 78, 63–67. 10.1016/j.appet.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jones BA, Jackson L, Yi R, & Bickel WK (2014). Discounting of money and sex: Effects of commodity and temporal position in stimulant dependent men and women. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 1652–1657. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Reed DD, DiGennaro Reed FD, & Bickel WK (2016). The behaviroal and neuroeconomics of reinforcer pathologies: Implications for managerial and health decision making. Managerial and Decision Economics, 37, 274–293. 10.1002/mde.2716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan BA, Foster RN, Reed DD, Amlung M, Murphy JG, & MacKillop J (2018). Understanding alcohol motivation using the Alcohol Purchase Task: A methodological systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191, 117–140. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan BA, Reed DD, Murphy JG, Henley AJ, DiGennaro Reed FD, Roma PG, & Hursh SR (2017). Time constraints in the alcohol purchase task. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25, 186–197. 10.1037/pha0000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, & Petry NM (2004). Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction, 99(4), 461–471. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00669.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, & Schoepflin FJ (2013). Predicting domain-specific outcomes using delay and probability discounting for sexual versus monetary outcomes. Behavioural Processes, 96, 71–78. 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, Schoepflin FJ, Green R, & Jenks C (2011). Discounting of hypothetical and potentially real outcomes in nicotine-dependent and nondependent samples. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 19, 263–274. 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemley SM, Fleming WA, & Jarmolowicz DP (2017). Behavioral economic predictors of alcohol and sexual risk behavior in college drinkers. The Psychological Record, 67, 197–211. 10.1007/s40732-017-0239-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemley SM, Kaplan BA, Reed DD, Darden AC, & Jarmolowicz DP (2016). Reinforcer pathologies: Predicting alcohol related problems in college drinking men and women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 167, 57–66. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luehring-Jones P, Dennis-Tiwary TA, Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Lindgren KP, Yarmush DE, & Erblich J (2016). Favorable associations with alcohol and impaired self-regulation: A behavioral economic analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 163, 172–178. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung M, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, & Munafo MR (2011). Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology, 216, 305–321. 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda R Jr., Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, McGeary JE, Swift RM, Tidey JW, & Gwaltney CJ (2010). Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(1), 106–114. 10.1037/a0017513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda R, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohesnow DJ, McGeary JE, Swift RM, Tidey JW, & Gwaltney CJ (2010). Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 106–114. 10.1037/a0017513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, & Murphy JG (2006). Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 14(2), 219–227. 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, & Murphy JG (2007). A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 89(2–3), 227–233. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Petry NM, Badger GJ, & Bickel WK (1997). Impulsive and self-control choices in opioid-dependent patients and non-drug-using control participants: Drug and monetary rewards. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 5(3), 256–262. 10.1037/1064-1297.5.3.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE (1987). An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In Commons ML, Mazur JE, Nevin JA, & Rachlin H (Eds.), Quantitative analysis of behavior (Vol. 5, pp. 55–73). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Fields HL, D’Esposito M, & Boettiger CA (2005). Impulsive responding in alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29 (12), 2158–2169. 10.1097/01.alc.0000191755.63639.4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH (1999). Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and nonsmokers. Psychopharmacology, 146(4), 455–464. 10.1007/PL00005491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monterosso JR, Ainslie G, Xu J, Cordova X, Domier CP, & London ED (2007). Frontoparietal cortical activity of methamphetamine-dependent and comparison participants performing a delay discounting task. Human Brain Mapping, 28(5), 383–393. 10.1002/hbm.20281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody LN, Tegge AN, & Bickel WK (2017). Cross-commodity delay discounting of alcohol and money in alcohol users. Psychological Record, 67(2), 285–292. 10.1007/s40732-017-0245-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Yurasek AM, Skidmore JR, MacKillop J, & McDevitt-Murphy ME (2015). Behavioral economic predictors of brief alcohol intervention outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(6), 1033–1043. 10.1037/ccp0000032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, & MacKillop J (2006). Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 14(2), 219–227. 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, & Pederson AA (2009). Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17(6), 396–404. 10.1037/a0017684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Yurasek AM, Meshesha LZ, Dennhardt AA, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, & Martens MP (2014). Family history of problem drinking is associated with less sensitivity of alcohol demand to a next-day responsibility. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(4), 653–663. 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo DA, Ait-Daoud N, Rege SV, Ding C, Gallion L, Davis S, & Holstege CP (2018). Differentials and trends in emergency department visits due to alcohol intoxication and co-occuring conditions among students in a U.S. public university. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 183, 89–95. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo DA, Rege SV, Ait-Daoud N, & Holstege CP (2018). Trends in incidence and risk markers of student emergency department visits with alcohol intoxication in a U.U. public university: A longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 188, 341–347. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM (2001). Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology, 154(3), 243–250. 10.1007/s002130000638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen EB, Lawyer SR, & Reilly W (2010). Percent body fat is related to delay and probability discounting for food in humans. Behavioural Processes, 83 (1), 23–30. 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Stroing DR, & Colder CR (2006). Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 67(1), 169–177. 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins BY, Dearing KK, & Epstein LH (2010). Delay discounting moderates the effect of food reinforcement on energy intake among non-obese women. Appetite, 55(3), 420–425. 10.1016/j.appet.2010.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffer CE, Christensen DR, Landes RD, Carter LP, Jackson L, & Bickel WK (2014). Delay discounting rates: A strong prognostic indicator of smoking relapse. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 1682–1689. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffer CE, MacKillop J, McGeary J, Landes RD, Carter L, Yi R, Jones B, Christensen D, Stitzer M, Jackson L, & Bickel WK (2012). Delay discounting, locus of control, and cognitive impulsiveness independently predict tobacco dependence treatment outcomes in a highly dependent, lower socioeconomic group of smokers. American Journal on Addictions, 21(3), 221–232. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00224.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveri MM (2012). Adolescent brain development and underage drinking in the united states: Identifying risks of alcohol use in college populations. Harvard Review of Psaychiatry, 20(4), 189–200. 10.3109/10673229.2012.714642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Ryan SR, Fu H, Landes RD, Jones BA, Bickel WK, & Budney AJ (2011). Delay discounting predicts adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 10.1037/a0026543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2010). A dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Psychobiology, 52(3), 216–224. 10.1002/dev.20445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze YY, Stein JS, Bickel WK, Paluch RA, & Epstein LH (2017). Bleak present, bright future: Online episodic future thinking, scarcity, delay discounting, and food demand. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(4), 683–697. 10.1177/2167702617696511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, & Murphy JG (2015). The behavioral economics of driving after drinking among college drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(5), 896–904. 10.1111/acer.12695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, & Simpson CA (1998). Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers [Comparative Study]. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 6(3), 292–305. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9725113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio Y, Higgins ST, Heil SH, McKerchar TL, Badger GJ, Skelly JM, & Dantona RL (2011). Delay discounting is associated with treatment response among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 19 (3), 243–248. 10.1037/a0023617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, & Castillo S (1994). Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college. A national survey of students at 140 campuses [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 272(21), 1672–1677. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7966895 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidberg S, Secades-Villa R, García-Pérez Á, González-Roz A, & Fernández-Hermida JR (2019). The synergistic effect of cigarette demand and delay discounting on nicotine dependence among treatment-seeking smokers. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(2), 146–152. 10.1037/pha0000248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wileyto EP, Audrain-McGovern J, Epstein LH, & Lerman C (2004). Using logistic regression to estimate delay-discounting functions. Behavior, Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 36, 41–51. 10.3758/BF03195548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ME (2017). Discounting: A practical guide to multilevel analysis of indifference data. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 108(1), 97–112. 10.1002/jeab.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ME (2018). Discounting: A practical guide to multilevel analysis of choice data. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 109(2), 293–312. 10.1002/jeab.316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvorsky I, Nighbor TD, Kurti AN, DeSarno M, Naudé G, Reed DD, & Higgins ST (2019). Sensitivity of hypothetical purchase task indices when studying substance use: A systematic literature review. Journal of Preventative Medicine, 182. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]