Abstract

Context:

Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is a dangerous necrotizing infection of the kidney involving the diabetics with a high case fatality rate. Recent medical literature has shown shifting of treatment strategy from conventional radical approach to minimally invasive approach.

Aims:

The aim of our study was to assess the role of minimally invasive stepwise decompression techniques in the management of EPN and preservation of the renal unit.

Settings and Design

: This was a retrospective observational study conducted from June 2017 to April 2020 at a tertiary care centre.

Material and Methods:

We reviewed the hospital online records of 18 patients diagnosed with EPN for patient demographics, clinical profiles, co-morbidities, laboratory and, radiological investigations, surgical interventions performed and the outcomes. The severity of EPN was graded as per the Huang classification. Patients underwent surgical interventions as per the treatment protocol and response was assessed.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Descriptive statistics was applied.

Results:

Diabetes mellitus was present in 15 (83.3%) patients along with urinary tract obstruction in 8 (44.4%) patients. Flank pain (77.7%) was the most common presenting clinical feature while Escherichia coli (55.5%) were the most common causative organism. Most patients (50%) had Type- II EPN, all of which were managed successfully by minimally invasive procedures. In total seventeen patients (94.4%) responded well while one patient (5.5%) underwent nephrectomy with no mortality.

Conclusions:

Renal salvage in EPN requires multidisciplinary approach including the initial medical management followed by properly selected stepwise decompressive surgical techniques. Conservative management and decompression techniques have shown to improve patient's outcome, reducing the traditional morbidity associated with nephrectomy.

KEY WORDS: Diabetes mellitus, emphysematous pyelonephritis, minimally invasive techniques, upper urinary tract infection

Introduction

Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is a potentially life-threatening necrotising infection affecting the renal unit with the characteristic presence of gas having reported mortality of 19% to 43%.[1,2]

EPN is common in immune-compromised diabetic females with obstructed urinary system having classical triad of fever, vomiting and flank pain.[3] Presently, non-contrast computed tomography of kidney, ureter, and bladder (NCCT-KUB) is the imaging modality of choice.[4]

Traditionally, early nephrectomy has been considered the treatment of choice for EPN.[5,6] Recently, minimally invasive interventions have gained momentum due to better imaging modalities and advances in image-guided procedures.[7] In this retrospective observational study, we present 18 patients of EPN with the primary aim to assess the various minimally invasive techniques in a sequential (step wise) manner in salvaging the renal unit.

Subjects and Methods

This was a retrospective observational study comprising of 18 patients, which was conducted from June 2017 to April 2020 at a tertiary care centre. This study was approved by the institute ethical committee.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were:

Inclusion criteria-

Signs and symptoms of upper urinary tract infection, and

Presence of gas in the renal collecting system, parenchyma and surrounding tissue as demonstrated on NCCT-KUB.

Exclusion criteria-

Presence of communicating fistula between the urinary system and small or large bowel, and

Recent history of urinary catheterisation, trauma, urinary instrumentation or internal or external drainage.

Patient demographics, clinical profiles, co-morbidities, laboratory investigations (haematological and urine), radiological investigations, surgical interventions performed and outcomes were assessed. Clinical parameters which were noted included presence of fever, flank pain/tenderness, abdominal lump, altered consciousness and hemodynamic instability at admission. Laboratory investigations which were assessed included serum creatinine, glycosylated haemoglobin, total leukocyte count, platelet count, pyuria, macro-haematuria and urine culture & sensitivity.

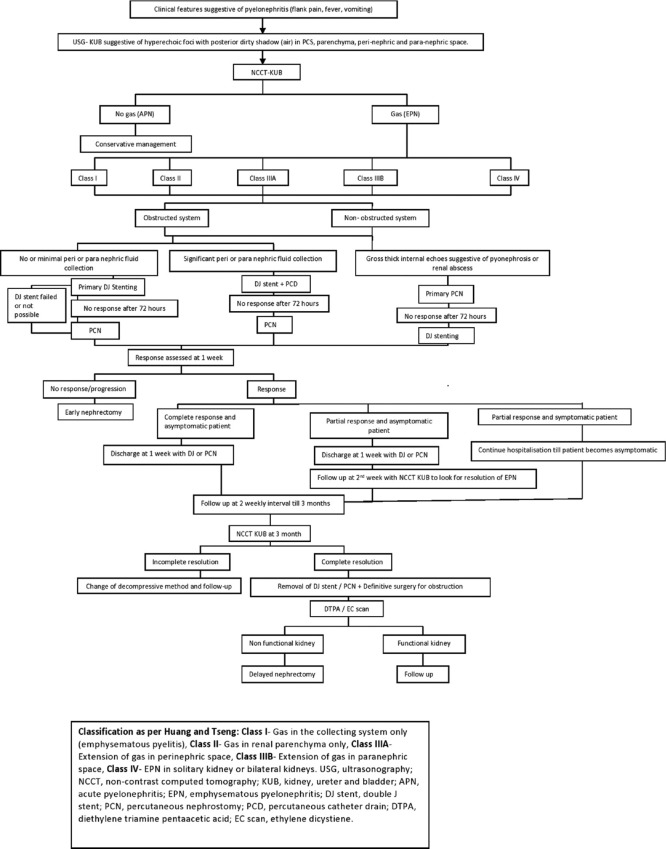

All the patients who had presented with clinical features suspicious of EPN initially underwent ultrasonography (USG) of KUB region [Figure 1]. Based upon the USG findings of pyelonephritis, patients were subjected to NCCT-KUB scan and were classified as per the Huang and Tseng classification into:

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the management of emphysematous pyelonephritis

Class I- Gas in the collecting system only (emphysematous pyelitis)

Class II- Gas in renal parenchyma only

Class IIIA- Extension of gas in perinephric space

Class IIIB- Extension of gas in paranephric space

Class IV- Gas in solitary kidney or bilateral kidneys

All the patients diagnosed with EPN were admitted. The initial management in the form of intravenous fluid, antipyretics, analgesics and broad-spectrum antibiotics were started. Antibiotics were subsequently changed as per the urine culture & sensitivity report. Placement of per urethral catheter was done in all patients and the vitals were monitored.

Immediately after the initial management, based upon CT classification, patients underwent surgical interventions as per the treatment protocol shown [Figure 1]

Primary DJ stenting was done in all the patients of EPN except patients with gross pyonephrosis.

Primary PCN insertion was done in the patients with radiological findings suggestive of hydronephrosis with thick internal echoes and in the patients in whom primary DJ stenting failed.

DJ stent with PCD insertion was done in the patients with significant perinephric or paranephric collection.

Primary DJ +/- PCN +/- PCD insertion was done in cases not responding to primary DJ stenting and/or any other single form of internal/external drainage.

DJ stenting, PCN and PCD insertion were preferably done under local anaesthesia using fluoroscopic/USG guidance. The size of the DJ stent and Malecot's catheter or pigtail catheter (used as PCN or PCD) was decided on the basis of age and height of the patient. Post procedure the response assessment was done in terms of improvement or progression of primary clinical symptoms, laboratory and NCCT-KUB findings at 72 hours, 1 week and 2 weeks post procedure and were classified as responsive or non-responsive or progressive. [Figure 2] During the same admission, as per the response, if needed additional minimally invasive surgical procedures or early nephrectomy was carried out.

Figure 2.

Non-contrast computed tomography - Kidney Ureter Bladder (KUB) showing (a) type-II emphysematous pyelonephritis of right kidney; (b) partial response at 2 weeks to primary DJ stent; (c) complete resolution at 1 month; (d) type-II emphysematous pyelonephritis of right kidney; (e) partial response at 72 hours to primary percutaneous nephrostomy; (f) complete resolution at 6 weeks post DJ stent at 72 hours; (g) type-IIIB emphysematous pyelonephritis of right kidney and left acute pyelonephritis; (h) bilateral DJ stenting done; (i) No resolution of emphysematous pyelonephritis at one week post DJ stenting and percutaneous drain requiring right simple nephrectomy; (j) bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis with left DJ stent (type- IV)

Patients who had PCD, had it removed when the drain output was nil or minimal for 48 hours along with USG-KUB showing confirmation of resolution of the collection. All the patients were discharged with internal and/or external tube required for urinary drainage (DJ/PCN) with advice to follow-up every 2 weekly for up to 3 months. At the end of 3 months, confirmation of resolution of EPN was done with NCCT-KUB before removal of DJ stent/PCN. In case of complete resolution of EPN, DJ stent and/or PCN were removed. After removal of DJ stent/PCN, functional nuclear scan in the form of diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA)/ethylene dicystiene (EC) scan, based upon serum creatinine level, was done. In case of non-functioning kidney with or without resolution of EPN, patients were considered for delayed nephrectomy.

After the collection of data for the said time period, descriptive statistics were applied to the previously mentioned parameters and the data was interpreted. The categorical variables were presented as counts with respective proportions and whereas continuous variables were presented as mean with standard deviation and median with range.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the 18 study patients are shown [Table 1]. A total of 18 patients (six males and 12 females) were included in the study, with a mean age of 56 years (range 30-80). Out of the 18 patients, 15 (83.3%) had diabetes. Out of 18 patients, eight patients (44.4%) had obstructed urinary system (hydronephrosis with or without hydroureter) of which five patients (27.7%) had urolithiasis (two patients with ureteric calculus and three patients with renal calculus) and in the remaining three patients (16.6%) with obstruction, we were not able to find any identifiable cause.

Table 1.

Patient profile, computed tomography classification, management and outcome (n = 18)

| Age (years) | Sex | Co-morbidities | Type of system | Associated urolithiasis | Presence of HN/ HUN | CT classification | Treatment | Total no. of procedures | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | F | DM | Obstructed | Present | HN | Class II | DJ stent+PCD | 2 | Salvaged |

| 39 | F | Nil | Unobstructed | - | - | Class IIIA | DJ stent+PCD | 2 | Salvaged |

| 71 | M | DM, HTN | Obstructed | Present | HN | Class II | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 68 | M | HTN | Unobstructed | - | - | Class I | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 61 | F | DM, HTN | Obstructed | Present | HN | Class II | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 80 | M | DM | Obstructed | - | - | Class IIIA | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 57 | M | DM | Unobstructed | - | - | Class II | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 51 | F | DM, HTN | Unobstructed | - | - | Class II | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 30 | F | DM, HTN | Obstructed | - | HN | Class IIIB | DJ stent+PCD | 2 | Salvaged |

| 45 | F | DM | Unobstructed | - | - | Class II | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 55 | M | DM | Unobstructed | - | - | Class IV | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 50 | F | DM | Unobstructed | - | - | Class IIIA | DJ stent+PCD | 2 | Salvaged |

| 53 | F | DM | Unobstructed | - | - | Class II | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 60 | F | DM, HTN | Obstructed | Present | HUN | Class I | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 65 | M | DM, HTN | Unobstructed | - | - | Class IIIB | DJ+PCD+PCN+Early Nephrectomy | 4 | Non- salvageable |

| 50 | F | Nil | Obstructed | Present | HUN | Class II | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

| 54 | F | DM | Unobstructed | - | - | Class II | Primary PCN+DJ stent | 2 | Salvaged |

| 55 | F | DM | Obstructed | - | HN | Class IIIA | DJ stent | 1 | Salvaged |

M - Male; F - Female; CT - Computed Tomography; DJ – Double J; PCD- Percutaneous drain; PCN- Percutaneous Nephrostomy; DM- Diabetes Mellitus; HTN- Hypertension; HN- Hydronephrosis; HUN- Hydroureteronephrosis

The clinical, laboratory and microbiological characteristics are shown [Table 2]. Flank pain (77.7%) was the most common presenting clinical feature followed by fever (72.2%), dysuria (61.1%), nausea-vomiting (27.7%) and altered consciousness (11.1%). Among the clinical signs, renal angle tenderness (83.3%) was the most common followed by palpable lump (16.6%) and hypotension (16.6%). Laboratory parameters revealed deranged renal function in all (100%) cases, followed by leucocytosis (88.8%), raised HbA1c (83.3%) and low platelet count (38.8%). Urine analysis showed presence of pyuria in 83.3% of the cases while Escherichia coli (55.5%) was the most common organism isolated in urine culture followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (27.7%).

Table 2.

Demography, clinical features, laboratory and microbiological findings on admission

| No. of patients (n=18) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) ± SD | 56 ± 11.38 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 06 | 33.3 |

| Female | 12 | 66.6 |

| Clinical symptoms | ||

| Flank/abdominal pain | 14 | 77.7 |

| Fever (Body temperature>38oC) | 13 | 72.2 |

| Dysuria and frequency | 11 | 61.1 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 05 | 27.7 |

| Altered consciousness (disorientation to time, place and person) | 02 | 11.1 |

| Clinical signs | ||

| Renal angle tenderness | 15 | 83.3 |

| Abdominal lump | 03 | 16.6 |

| Hypotension (systolic B.P<90 mm of Hg) | 03 | 16.6 |

| Blood investigations | ||

| Deranged renal function (Serum creatinine>2.5 mg/dl) | 18 | 100 |

| Leucocytosis (> 11 x 109/L) | 16 | 88.8 |

| Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c>6.5%) | 15 | 83.3 |

| Low platelet count (<120 x 109/L) | 07 | 38.8 |

| Urine analysis | ||

| Pyuria (WBC>10/HPF) | 15 | 83.3 |

| Macro-haematuria (RBC>100/HPF) | 05 | 27.7 |

| Urine culture | ||

| Echerichia coli | 10 | 55.5 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | 05 | 27.7 |

| Sterile | 03 | 16.6 |

Based upon NCCT-KUB findings, two patients (11.1%) were classified as class I EPN, nine patients (50%) as class II EPN, four patients (22.2%) as class IIIA, two patients (11.1%) as class IIIB EPN and one patient (5.5%) as class IV EPN. Primary DJ stenting was done in 17 patients (94.4%), primary PCN with DJ stenting was done in one patient (5.5%), DJ stent with PCD was done in four patients (22.2%) and one patient (5.5%) underwent early nephrectomy as the patient did not respond to previous DJ stenting, PCD and PCN placement.

No patient required delayed nephrectomy. Of 18 patients, seven (38.8%) had more than one high risk prognostic factors [Table 3]. Five patients (27.7%) required two procedures, one patient (5.5%) required three procedures before undergoing early nephrectomy and rest were managed by a single procedure. The overall survival rate was 100%. The renal unit was salvageable in 17 patients (94.4%) [Table 1]. All eighteen patients were followed up for a period of 3 months. On follow-up, all 17 patients had GFR >10 ml/min or ERPF >30 ml/min of the affected kidney on dynamic renogram, based upon which no patient required delayed nephrectomy during follow-up.

Table 3.

Computed tomography classification in relation to management strategies and prognostic factors

| CT classification(Huang & Tseng) | High risk prognostic factors (> 1) | Management |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DJ stenting | Primary PCN+DJ stent | DJ stent+PCD | Early Nephrectomy | Late Nephrectomy | |||

| Class I (n, %) | - | 02 | - | - | - | - | 02 |

| Class II (n, %) | 03 | 07 | 01 | 01 | - | - | 09 |

| Class IIIA (n, %) | 02 | 02 | - | 02 | - | - | 04 |

| Class IIIB (n, %) | 02 | - | - | 01 | 01 | - | 02 |

| Class IV (n, %) | - | 01 | - | - | - | - | 01 |

One patient who needed nephrectomy was a 65 years old male with DM and HTN. On admission, he was diagnosed with Class IIIB EPN on right side and Acute Pyelonephritis in the left side which was initially managed with bilateral DJ stenting. At 72 hours, NCCT-KUB was done which showed increase in right parenchymal destruction and peri-nephric collection for which we placed PCD and PCN. Even after placement of PCN and PCD, there was no improvement in clinical, laboratory and radiological parameters at 1 week, with patient developing features of urosepsis with raised total leucocytic counts and serum creatinine with NCCT-KUB suggesting complete destruction of right renal parenchyma, so decision was taken for right open simple nephrectomy. Patient was discharged with uneventful post-operative period.

Discussion

EPN is an uncommon necrotizing infection seen predominantly in diabetic patients. It was first reported by Kelly and MacCallum in 1898, but it was Schultz and Klorfein in 1962 who first coined the term Emphysematous pyelonephritis.[3,8] It has been found to be more common in females, with some studies suggesting male: female ratio from 1:1.6 to 3:43 as seen in our study.[7,9] The increased incidence of EPN in females may be due to their increased susceptibility to urinary tract infection.[10]

The exact pathogenic mechanism of EPN is unclear but Huang and Tseng had described four key factors involved in the pathogenesis: gas (carbon dioxide and hydrogen) forming bacteria, high tissue glucose level, defective renal tissue perfusion and impaired host immune response. Our patients also had poor glycaemic control. Unrelieved urinary tract obstruction leads to urinary stasis and resultant backpressure changes making anti-bacterial therapy relatively ineffective.[11]

So, in our study we performed immediate decompression of the urinary system in all our patients. Glucose-fermenting bacteria, Escherichia coli is the most common causative organism for EPN isolated from urine in 47-90% of the cases, followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus vulgaris.[12,13]

Clinically EPN is often suggestive of acute pyelonephritis with fever, flank pain and pyuria been the most common clinical manifestation. Chen et al.,[14] demonstrated renal angle tenderness as the most common clinical finding and Shokeir et al.,[15] reported deranged renal function (80%) and shock (15%) in their study population which is similar to our study [Table 2]. Rarely, EPN can be asymptomatic in which case conservative management can be attempted.[16]

Diagnosis of EPN is made radiologically, with CT scan been the most definitive modality. Contrast enhanced CT helps in better evaluation of functional status of the renal units as well as characteristics of intra-parenchymal gas. However, in patients with deranged renal function, NCCT-KUB scan may suffice. CT scan is also helpful in monitoring the treatment response.

Chen et al.,[14] recommended a repeat CT scan after four to seven days to look for any non-communicating air/fluid collections, which might require further surgical drainage procedure. Similarly, in our study, we repeated NCCT-KUB after three days, one week and 2 weeks post-intervention to look for resolution of EPN.

There are some studies which had focused on factors associated with poor outcome. Huang et al.,[2] reported that initial presentation of patients with thrombocytopenia, altered consciousness, deranged renal function and shock had been associated with higher mortality. Recently, Kapoor et al.,[17] reported increased mortality rates with initial presentation with renal failure, low platelet count, altered mental status and severe hyponatremia along with need for nephrectomy in cases with extensive renal parenchymal destruction.

In 2000, Huang and Tseng suggested that nephrectomy could provide the best management, if promptly attempted for extensive EPN (Class III and class IV) having a fulminant course (>1 risk factors). In our study, seven patients (three patients of class II EPN and four patients of class III A and IIIB) had simultaneous presence of >1 risk factor. [Table 3] Out of the four patients with extensive EPN (class III), only one patient required nephrectomy while the rest were successfully managed with minimally invasive approaches. There was no mortality in our study. Our study shows that these cases of higher grades can be managed by conservative and MIS techniques though further studies with a larger sample size is needed to support our findings. The excellent outcome can be explained due to early diagnosis, prompt management, close monitoring and follow-up of the patients. Similar results have been reported by Lu et al.[18]

Treatment of EPN is evolving. Ahlering et al.,[19] and Klein et al.,[20] recommended emergency nephrectomy for patients with EPN after initial stabilisation and antibiotic therapy with reported mortality rate of 42% and 38% respectively. But in recent times, minimally invasive approaches in the management strategy of EPN has gained momentum. Somani et al.,[21] in their study analysed that there was 25% mortality rate associated with emergency nephrectomy as compared to 13.5% mortality with medical management with PCD alone and 6.6% mortality with PCD and elective nephrectomy. Dhabalia et al.,[22] in their study showed that nephrectomy had a high mortality as compared to minimally invasive techniques. Similarly findings were shown by Das et al.,[23] Aswathaman,[24] Alsharif[25] Similarly findings were shown by Kapoor et al.,[17] and Aboumarzouk et al.,[26] Our study also had a good success rate (no mortality) reflecting the evolving trend in the management of EPN, following a stepwise protocol with minimally invasive procedures (DJ stenting first followed by PCD or PCN) which is quite similar to the management algorithm adopted in the study done by Jain et al.[27] [Table 4]

Table 4.

Management specific outcomes of patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis

| Study | Sample size | Type of procedure | Resolution % | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park (2006)[32] | 17 | Nephrectomy | 90% | Early nephrectomy has a high resolution rate |

| Medical management (MM) | 50% | |||

| Minimally Invasive technique (MIT) | 66% | |||

| Das (2016)[23] | 15 | MM | 100% | Medical management with MIT has a very high success rate. |

| MIT | 100% | |||

| Misgar (2015) [28] | 26 | Nephrectomy | 100% | Conservative approach has 88.5% success rate |

| MM | 100% | |||

| MIT | 100% | |||

| Chan (2005) [11] | 10 | MIT | 100% | Medical management with MIT has a very high success rate. |

| Present study | 18 | MIT | 94.4% | Minimally invasive decompressive surgical techniques have excellent results |

| Nephrectomy | 100% | |||

Misgar et al.[28] in his study showed that out of 66.6% of cases of Class III & IV, only 7.7% of cases required nephrectomy. Similarly, Sharma in his study of 14 patients, had five patients (36%) of class III EPN, of which one patient (7.14%) required open surgical drainage with no mortality, the outcome of which is very similar to our study. In contrast, Elawdy et al.,[29] in his study had eight patients of Class III EPN which was managed medically, of which 4 patients required nephrectomy with no mortality.

However, as shown by Boakes et al.,[30] in deteriorating patients who fail to improve with antibiotics and minimally invasive procedures, especially Class III & IV, prompt surgical intervention should be considered [Figure 1] within 1 week of diagnosis. A recent study by Sokhal et al.,[7], Irfaan et al.,[31], and Park et al.[32] highlighted the need for an emergency nephrectomy as a salvage procedure for those patients who are not responding to antibiotics and minimally invasive procedures.

In our study, one patient had bilateral EPN (class IV) which was managed successfully with DJ stenting, as only parenchymas were involved with minimal destruction and no perinephric or paranephric fluid collection. Nephrectomy in such patients would lead to lifelong renal replacement therapy. Successful non-surgical management of bilateral EPN has been previously reported.[29,33]

It was Hudson who first demonstrated fluoroscopically guided percutaneous approach with successful clinical results.[4] Following this many authors had good outcomes with USG or CT –guided PCD.[13] In contrast, some authors suggested that USG-guided PCD was not suitable in patients with gas forming infections, due to significant distal shadowing and reverberation artifacts making correct placement of PCD difficult.[34] However in our study, we had good results with ultrasonography for PCN and PCD insertion and fluoroscopy for DJ stent insertion with good accuracy.

The limitation of our study is that it is retrospective in nature due to the rarity of the disease. However, we suggest a better prospective randomised study for better evaluation of treatment strategies and its outcome.

Conclusion

Minimally invasive decompressive surgical techniques have excellent results in preserving renal function in management of EPN. Presence of risk factors may not always be associated with high mortality if the patients are treated aggressively in the initial phase of management with minimally invasive techniques.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Michaeli J, Mogle P, Perlberg S, Heiman S, Caine M. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. J Urol. 1984;131:203–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)50309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang JJ, Tseng CC. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Clinicoradiological classification, management, prognosis, and pathogenesis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:797–805. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz EH, Jr, Klorfein EH. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. J Urol. 1962;87:762–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)65043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson MA, Weyman PJ, Vander Vliet AH, Catalona WJ. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Successful management by percutaneous drainage. J Urol. 1986;136:884–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn SR, Dewolf WC, Gonzalez R. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Report of 3 cases treated by nephrectomy. J Urol. 1975;114:348–50. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)67026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook DJ, Achong MR, Dobranowski J. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. Complicated urinary tract infection in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1989;12:229–32. doi: 10.2337/diacare.12.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokhal AK, Kumar M, Purkait B, Jhanwar A, Singh K, Bansal A, et al. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Changing trend of clinical spectrum, pathogenesis, management and outcome. Turk J Urol. 2017;43:202–9. doi: 10.5152/tud.2016.14227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly HA, MacCallum WG. Pneumaturia. JAMA. 1898;31:375–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pontin AR, Barnes RD. Current management of emphysematous pyelonephritis. Nat Rev Urol. 2009;6:272–9. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan YL, Lee TY, Bullard MJ, Tsai CC. Acute gas-producing bacterial renal infection: Correlation between imaging findings and clinical outcome. Radiology. 1996;198:433–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.198.2.8596845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan PH, Kho VKS, Lai SK, Yang CH, Chang HC, Chiu B, et al. Treatment of emphysematous pyelonephritis with broad-spectrum antibacterials and percutaneous renal drainage: An analysis of 10 patients. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005;68:29–32. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hildebrand TS, Nibbe L, Frei U, Schindler R. Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis caused by Candida infection. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:E10. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma PK, Sharma R, Vijay MK, Tiwari P, Goel A, Kundu AK. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Our experience with conservative management in 14 cases. Urol Ann. 2013;5:157–62. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.115734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen MT, Huang CN, Chou YH, Huang CH, Chiang CP, Liu GC. Percutaneous drainage in the treatment of emphysematous pyelonephritis: 10-year experience. J Urol. 1997;157:1569–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shokeir AA, El-Azab M, Mohsen T, El-Diasty T. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: A 15-year experience with 20 cases. Urology. 1997;49:343–6. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeung A, Cheng CH, Chu P, Man CW, Chau H. A rare case of asymptomatic emphysematous pyelonephritis. Urol Case Rep. 2019;26:100962. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2019.100962. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr. 2019.100962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapoor R, Muruganandham K, Gulia AK, Singla M, Agrawal S, Mandhani A, et al. Predictive factors for mortality and need for nephrectomy in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis. BJU Int. 2010;105:986–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu YC, Chiang BJ, Pong YH, Huang KH, Hsueh PR, Huang CY, et al. Predictors of failure of conservative treatment among patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:418. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahlering TE, Boyd SD, Hamilton CL, Bragin SD, Chandrasoma PT, Lieskovsky G, et al. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: A 5-year experience with 13 patients. J Urol. 1985;134:1086–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47635-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein FA, Smith MJ, Vick CW, 3rd, Schneider V. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Diagnosis and treatment. South Med J. 1986;79:41–6. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198601000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Somani BK, Nabi G, Thorpe P, Hussey J, Cook J, N'Dow J, et al. Is percutaneous drainage the new gold standard in the management of emphysematous pyelonephritis? Evidence from a systematic review. J Urol. 2008;179:1844–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhabalia JV, Nelivigi GG, Kumar V, Gokhale A, Punia MS, Pujari N. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Tertiary care center experience in management and review of the literature. Urol Int. 2010;85:304–8. doi: 10.1159/000315056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das D, Pal DK. Double J stenting: A rewarding option in the management of emphysematous pyelonephritis. Urol Ann. 2016;8:261–4. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.184881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aswathaman K, Gopalakrishnan G, Gnanaraj L, Chacko NK, Kekre NS, Devasia A. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Outcome of conservative management. Urology. 2008;71:1007–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alsharif M, Mohammedkhalil A, Alsaywid B, Alhazmy A, Lamy S. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Is nephrectomy warranted? Urol Ann. 2015;7:494–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.158503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aboumarzouk OM, Hughes O, Narahari K, Coulthard R, Kynaston H, Chlosta P, et al. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Time for a management plan with an evidence-based approach. Arab J Urol. 2014;12:106–15. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain A, Manikandan R, Dorairajan LN, Sreenivasan SK, Bokka S. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Does a standard management algorithm and a prognostic scoring model optimize patient outcomes? Urol Ann. 2019;11:414–20. doi: 10.4103/UA.UA_17_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misgar RA, Wani AI, Bashir MI, Pala NA, Mubarik I, Lateef M, et al. Successful medical management of severe bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis: Case studies. Clin Diabetes. 2015;33:76–9. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.33.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elawdy MM, Osman Y, Abouelkheir RT, El-Halwagy S, Awad B, El-Mekresh M. Emphysematous pyelonephritis treatment strategies in correlation to the CT classification: Have the current experience and prognosis changed.? Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51:1709–13. doi: 10.1007/s11255-019-02220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boakes E, Batura D. Deriving a management algorithm for emphysematous pyelonephritis: Can we rely on minimally invasive strategies or should we be opting for earlier nephrectomy.? Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49:2127–36. doi: 10.1007/s11255-017-1706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Irfaan AM, Shaikh NA, Jamshaid A, Qureshi AH. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: A single center review. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36:S83–6. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.ICON-Suppl.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park BS, Lee SJ, Kim YW, Huh JS, Kim JI, Chang SG. Outcome of nephrectomy and kidney-preserving procedures for the treatment of emphysematous pyelonephritis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006;40:332–8. doi: 10.1080/00365590600794902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuchay MS, Laway BA, Bhat MA, Mir SA. Medical therapy alone can be sufficient for bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis: Report of a new case and review of previous experiences. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46:223–7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0446-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuo YT, Chen MT, Liu GC, Huang CN, Huang CL, Huang CH. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Imaging diagnosis and follow-up. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 1999;15:159–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]