Abstract

Rationale

The COVID-19 pandemic has had numerous negative effects globally, contributing to mortality, social restriction, and psychological distress. To date, however, the majority of research on the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has focused on negative psychological outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Objective

Although there is debate about the constructive vs. illusory nature of post-traumatic growth (PTG), it has been found to be prevalent in a broad range of trauma survivors, including individuals affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The objective of this study was to identify pre- and peri-pandemic factors associated with pandemic-related PTG in a national sample of U.S. veterans.

Methods

Data were analyzed from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study, which surveyed a nationally representative cohort of 3078 U.S. veterans. A broad range of pre-pandemic and 1-year peri-pandemic factors associated with pandemic-related PTG were evaluated. Curve estimation and receiver operating characteristic curve analyses were conducted to characterize the association between pandemic-related PTSD symptoms and PTG.

Results

Worries about the effect of the pandemic on one's physical and mental health, PTG in response to previous traumas (i.e., new possibilities and improved interpersonal relationships), and pandemic-related avoidance symptoms were the strongest correlates of pandemic-related PTG. An inverted-U shaped relationship provided the best fit to the association between pandemic-related PTSD symptoms and endorsement of PTG, with moderate severity of PTSD symptoms optimally efficient in identifying veterans who endorsed PTG.

Conclusions

Results of this study suggest that psychosocial interventions that promote more deliberate and organized rumination about the pandemic and enhance PTG in response to prior traumatic events may help facilitate positive psychological changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic in U.S. military veterans. Longitudinal studies on functional correlates of PTG may help inform whether these changes are constructive vs. illusory in nature.

Keywords: Post-traumatic growth, Trauma, COVID-19, Veterans

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a pervasive global impact, causing mortality, social restriction, and psychological distress (Reger et al., 2020). Consequently, there have been concerns of a possible surge in mental health problems in the general public, as well as high-risk populations, such as individuals with pre-existing psychiatric conditions (Reger et al., 2020). However, despite these grim forecasts, extant studies have observed stability in prevalence of severe psychological distress during the pandemic relative to the previous year (Breslau et al., 2021; Hill et al., 2021). Further, deaths by suicide have actually declined in the U.S. (Ahmad and Anderson, 2021) as well as in 21 upper-middle and high-income countries in 2020 (Pirkis et al., 2021). Other outcomes, such as the prevalence of suicidal ideation or alcohol use disorder have also been found to be relatively stable among U.S. military veterans nine-months into the pandemic (Na et al., 2021a, Na et al., 2021b; Nichter et al., 2021; Pietrzak et al., 2021).

To date, the majority of research on the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has focused on negative outcomes such as depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicidality (Czeisler et al., 2020; Ettman et al., 2020; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020; Na et al., 2021a, Na et al., 2021b). In contrast, relatively few studies have focused on potentially salutogenic outcomes such as posttraumatic growth (PTG) (Asmundson et al., 2021; Hamam et al., 2021; Pietrzak et al., 2021; Tamiolaki and Kalaitzaki, 2020; Vazquez et al., 2021; Zhai et al., 2021). PTG is defined as positive, meaningful psychological changes that individuals may experience after struggling with traumatic and stressful life events (Zoellner and Maercker, 2006), and has been linked to improved functioning (Tsai et al., 2015), as well as greater resilience to subsequent traumatic events (Tsai et al., 2016). Previous studies have also found that PTG could result from various traumas, including combat exposure (Pietrzak et al., 2010), assault (Kleim and Ehlers, 2009), and imprisonment during war (Feder et al., 2008). PTG is a complex phenomenon, with ongoing debate regarding its conceptualization and adaptivity (Zoellner and Maercker, 2006; Asmundson et al., 2021). Specifically, it has been suggested that while PTG may be real/constructive and lead to positive psychological changes, it is also possible that it may partly reflect dysfunctional attempts to cope with stressful events, such as avoidant or defensive coping strategies that lead to increased distress ( Boerner et al., 2017). For example, a recent study of Canadian and U.S. adults with high levels of COVID-related distress found that among those with high levels of PTG, 65% had a profile consistent with real/constructive growth (i.e., low COVID-19 stress-related disability and stable levels of distress over time), while 35% had a profile consistent with illusory growth (i.e., high COVID-19 stress-related disability and worsening distress over time) (Asmundson et al., 2021).

Military veterans are a unique population with previous exposures to various potentially traumatic and stressful life events, such as military training, deployment, and combat (Marini et al., 2020). However, it is unclear whether this unique history, as well as both adverse and positive mental health experiences related to it, may help mitigate the deleterious effects of such events (i.e., stress inoculation) or render this population more vulnerable to future disasters (i.e., stress sensitization), such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

An emerging body of research conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic has identified demographic, psychosocial, and personality factors associated with PTG, which have guided the selection of variables examined in the present study. Concerning demographics, older age (Patrick and Henrie, 2016; Vishnevsky et al., 2010), female gender (Vishnevsky et al., 2010), non-Caucasian ethnicity (Gallaway et al., 2011; Kleim and Ehlers, 2009; Mitchell et al., 2013; Vishnevsky et al., 2010), and previous life stressors such as traumatic exposures (Hafstad et al., 2011; Laufer and Solomon, 2006) have been positively linked to PTG. Although somewhat mixed, in general, psychiatric conditions such as PTSD (Morgan et al., 2017; Pietrzak et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2015), depression (Helgeson et al., 2006; Morrill et al., 2008; Powell et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2016), and anxiety (Xu et al., 2016) have been negatively associated with PTG. However, it should be also noted that the association between psychological distress and PTG is best characterized as a curvilinear, inverted U-shaped relationship, with moderate levels of distress associated with greater PTG relative to low or severe levels of distress (Kleim and Ehlers, 2009). Personality factors such as extraversion (Linley and Joseph, 2004; Tedeschi and Calhoun, 2004), agreeableness (Linley and Joseph, 2004), conscientiousness (Linley and Joseph, 2004), and openness to experiences (Linley and Joseph, 2004; Tedeschi and Calhoun, 2004) as well as protective psychosocial factors such as optimism (Bostock et al., 2009; Helgeson et al., 2006; Linley and Joseph, 2004; Prati and Pietrantoni, 2009; Tedeschi and Calhoun, 2004), social support (Forstmeier et al., 2009; Prati and Pietrantoni, 2009) and/or connectedness (McMillen et al., 1997; Tsai et al., 2015), religiosity/spirituality (Kleim and Ehlers, 2009; Prati and Pietrantoni, 2009; Tsai et al., 2015), and purpose in life (Tsai et al., 2015), have also been positively associated with PTG.

Studies that examined PTG during the COVID-19 pandemic have shown factors such as female gender (Kalaitzaki, 2021; Prieto-Ursua and Jodar, 2020; Yildiz, 2021), being married (Li et al., 2021b), greater adverse childhood experiences (Chi et al., 2020), higher economic status (Yildiz, 2021), greater psychological distress (Chi et al., 2020; Koliouli and Canellopoulos, 2021), knowing someone who died of COVID-19 complications (Prieto-Ursua and Jodar, 2020), actual COVID-19 infection (Prieto-Ursua and Jodar, 2020), and COVID-related PTSD symptoms (Pietrzak et al., 2021) to be linked to pandemic-related PTG.

In a recent study of a population-based sample of 3078 U.S. veterans, we found that 43.3% reported moderate or greater levels of COVID-19 pandemic-related PTG nine months into the pandemic; veterans who screened positive for pandemic-related PTSD symptoms reported a substantially higher prevalence of PTG than those who did not screen positive for these symptoms (Pietrzak et al., 2021). Further, greater pandemic-related improvements in interpersonal relationships and appreciation of life were associated with a lower likelihood of suicidal thoughts during the pandemic. However, this study did not examine pre- and peri-pandemic factors associated with PTG during the COVID-19 pandemic. Characterization of such factors may help inform clinical and policy interventions that may help veterans and other high-risk populations develop PTG and potentially be more resilient in future disasters. Toward this end, we analyzed data from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study (NHRVS) to examine a broad constellation of pre- and peri-pandemic risk and protective factors, informed by prior literature (Tsai et al., 2015, 2016), associated with pandemic-related PTG. Additionally, changes in household income (Pothisiri and Vicerra, 2021), trauma exposures (Lahav, 2020), and protective psychosocial characteristics (Li et al., 2021a; Yu et al., 2020) were also examined in light of data suggesting that such changes were associated with psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Data were analyzed from the 2019–2020 NHRVS, which surveyed a nationally representative sample of U.S. military veterans. A total of 4069 veterans completed the Wave 1 (median completion date: 11/21/2019) survey before the first documented COVID-19 case in the U.S. and 3078 (75.6%) completed a 1-year follow-up Wave 2 (median completion date: 11/14/2020) survey. Hereafter, the Wave 1 survey will be referred to “pre-pandemic survey” and Wave 2 survey will be referred to “peri-pandemic survey.” As described in greater detail elsewhere (Tsai et al., 2021), the NHRVS sample was drawn from KnowledgePanel®, a survey research panel of more than 50,000 U.S. households maintained by Ipsos, a survey research firm. To ensure generalizability of the results to the U.S. veteran population, poststratification weights were computed based on the demographic distribution of veterans in the U.S. Census Current Population Survey.

2.2. Assessments

Post-traumatic growth. COVID-19–associated PTG was assessed using the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory-Short Form (Cann et al., 2010; PTGI-SF) at Wave 2 (α = 0.92). Total scores (range: 0–50) and five subscales including personal strength, relating to others, new possibilities, spiritual change, and appreciation of life were assessed. Sample item: “Please indicate the degree to which you experienced these changes in your life as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic: I have a greater sense of closeness with others.” Endorsement of “moderate,” “great,” or “very great” growth on any of the PTGI-SF items was indicative of PTG. Given that the distribution of PTGI-SF scores was zero-inflated, non-normal, and positively skewed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test statistic = 0.19, p < 0.001), we dichotomized responses based on moderate or greater endorsement of any item; this approach to operationalizing endorsement of PTG has been used in a meta-analysis on the prevalence of PTG (Wu et al., 2019), as well as our recent study on the prevalence of COVID-19 pandemic-related PTG in the current sample (Pietrzak et al., 2021).

Background characteristics.Table 1 presents a detailed description of measures used to assess sociodemographic characteristics, psychological distress, cumulative trauma burden, adverse childhood experiences, physical health conditions, history of mental health treatment, personality traits (i.e., emotional stability, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness), social connectedness (i.e., emotional/instrumental social support, secure attachment style, and structural social support), and protective psychosocial factors (i.e., resilience, purpose in life, gratitude, community integration, optimism, social support, and curiosity/exploration).

Table 1.

Pre- and peri-pandemic factors examined in relation to pandemic-related post-traumatic growth in U.S. veterans.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Age, gender, race (white vs non-white), education (college graduate or higher vs up to high school diploma), marital status (married/living with partner vs unmarried), income ($60,000 or more vs less than $60,000), employment (working vs retired), and combat status (no combat exposure vs combat) |

|---|---|

| Background characteristics | |

| Psychological distress | MDD symptoms – participant responses on the two depressive symptoms of the PHQ-4 occurring in the past two weeks (Ω = 0.87); a score ≥3 was indicative of a positive screen for MDD (Kroenke et al., 2009); PTSD symptoms-assessed with the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; a score ≥33 was indicative of a positive screen for PTSD (Weathers et al., 2013a); GAD symptoms – participant responses on the two generalized anxiety items of the PHQ-4 occurring in the past two weeks (a score ≥3 was indicative of a positive screen for GAD (Kroenke et al., 2009). |

| Cumulative trauma burden | Count of potentially traumatic events on the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5;Weathers et al., 2013b). |

| Adverse childhood experiences | Score on Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (Felitti et al., 1998). |

| Number of medical conditions | Sum of number of medical conditions endorsed in response to question: “Has a doctor or healthcare professional ever told you that you have any of the following medical conditions?” (e.g., arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, asthma, kidney disease). Range: 0–24 conditions. |

| Personality traits | Assessed using the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; Gosling et al., 2003), a 10-item self-report brief measure of the “Big Five” personality traits of emotional stability (anxious vs confident and calm), extraversion (outgoing vs reserved), openness to experience (imaginative and inventive vs cautious and routine-like), agreeableness (friendly and cooperative vs detached), and conscientiousness (efficient and organized vs careless). |

| Engagement in mental health treatment | Positive endorsement of current treatment with psychotropic medication and/or psychotherapy or counseling: “Are you currently taking prescription medication for a psychiatric or emotional problem?” “Are you currently receiving psychotherapy or counseling for a psychiatric or emotional problem?” |

| Religiosity/spirituality | Score on the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL; Koenig and Bussing, 2010). |

| Social connectedness | |

| Structural social support | Number of close friends and family members. |

| Secure attachment | Choose one: a) I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; b) I find it relatively easy to get close to others (secure); c) I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like (Hazan and Shaver, 1990) |

| Emotional/instrumental social support | Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale-5; 5 items assessing how often each type of support is available when needed (e.g., “Someone to confide in or talk to about your problems”) on 5-point Likert scale: 1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time. Higher scores reflect greater perceived social support (Sherbournce and Stewart, 1991). |

| Protective psychosocial factor | |

| Resilience | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (CDRISC-10); 10 items (e.g., “I am able to adapt when changes occur”) on 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true to 5 = true nearly all the time; Campbell-Sills and Stein, 2007). |

| Purpose in life | Score on Purpose in Life Test-Short Form (Schulenberg et al., 2010). |

| Dispositional optimism | Score on single-item measure of optimism from Life Orientation Test-Revised (Scheier et al., 1994); “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best”; (rating 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

| Dispositional gratitude | Score on single-item measure of gratitude from Gratitude Questionnaire (McCullough et al., 2002); “I have so much in life to be thankful for”; (rating 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

| Perceived social support | Score on 5-item version of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale (Sherbournce and Stewart, 1991; Amstadter et al., 2011). |

| Curiosity/exploration | Score on single-item measure of curiosity/exploration from Curiosity and Exploration Inventory-II (Kashdan et al., 2009); “I frequently find myself looking for new opportunities to grow as a person (e.g., information, people, resources”); (rating 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

| Community integration | Perceived level of community integration: “I feel well integrated in my community (e.g., regularly participate in community activities)”; (rating 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

| Change variables (from pre-pandemic to peri-pandemic) | Changes in household income, psychological distress, traumas, and protective psychosocial characteristics |

| COVID-19 variables (peri-pandemic) | Hours consuming COVID-related media, COVID infection status (self, or household/non-household member), and knowing someone who died of COVID-19 using a questionnaire developed by the National Center for PTSD. COVID-related worries, social restriction stress, and financial stress were assessed based on the Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (NIMH Intramural Research Program, 2020). COVID-related worries (e.g., “In the past month, how worried have you been about being infected with coronavirus?”); COVID-social restriction stress (e.g., “How stressful have these changes in social contacts been for you?”); and COVID-related financial hardship (e.g., “In the past month, to what degree have changes related to the pandemic created financial problems for you or your family?”). COVID-related PTSD symptoms were assessed using the 4-item PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Geier et al., 2020) (score range = 0–16; sample item: “Thinking about the Coronavirus/COVID-19 pandemic, please indicate how much you have been bothered by repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the pandemic”); a score ≥5 is indicative of a positive screen for PTSD. Sum of traumas since baseline were assessed using a total count of past-year potentially traumatic events on the LEC-5 (Weathers et al., 2013b). |

DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, GAD = generalized anxiety disorder, LEC=Life Events Checklist, MDD = major depressive disorder, PHQ = patient health questionnaire, PTG = posttraumatic growth, PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Pandemic-associated factors. Table 1 presents a detailed description of measures used to assess COVID-19 infection status of veterans, household members, and non-household members; hours spent consuming COVID-related media; and knowing someone who died of COVID-19 using a questionnaire developed by the National Center for PTSD. Questions from the Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program Mood Spectrum Collaboration & Child Mind Institute of the NYS Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, 2020) were used to assess COVID-related worries, social restriction stress, and financial difficulties.

2.3. Data analysis

Item-level missing data (<5%), which were missing completely at random (MCAR) as per Little's MCAR test (all ps > 0.50), were imputed using chained equations. Data analyses proceeded in five steps. First, we computed bivariate correlations between any pandemic-related PTG and a broad range of background characteristics and pandemic-related variables (see Table 1). Second, variables that were significantly associated with pandemic-related PTG at the p < 0.05 level in bivariate analyses were entered into a hierarchical binary logistic regression analysis; background characteristics were entered in step 1, pandemic-related variables in step 2, and change variables in step 3. Third, we conducted planned post-hoc analyses of multi-dimensional variables (e.g., PTSD symptoms, protective psychosocial characteristics, COVID-19 pandemic-related stressors) to identify aspects of these variables that were most strongly associated with PTG; alpha was set to 0.01 for these analyses to reduce likelihood of Type I error. Fourth, significant variables from the logistic regression analysis were entered into a relative importance analysis, which computed the explained variance in pandemic-related PTG that is attributable to each independent variable while accounting for intercorrelations among these variables (Tonidandel and LeBreton, 2010). This analysis yields a relative weight (% variance explained) for each independent variable that collectively sums to the total R2 in predicting a dependent variable (weights are re-scaled to sum to 100% of the explained variance); this analytic approach represents an extension of regression modeling that allows one to model intercorrelations among independent variables when determining the relative importance of each independent variable in predicting variance in a dependent variable. Fifth, to examine the nature of the association between severity of PTSD symptoms and PTG, we fitted linear and quadratic functions between the severity of pandemic-related PTSD symptoms and probability of endorsing PTG from the logistic regression model. An analysis of variance was used to determine which function provided the best fit to these data and explained the most variance in predicting probability of endorsing PTG. We then conducted a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to identify the optimally efficient threshold of pandemic-related PTSD symptoms associated with endorsement of PTG.

3. Results

Table 2 shows sample characteristics, and results of bivariate correlations and a regression model examining factors associated with COVID-19 pandemic-related PTG.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics, and results of bivariate analyses and multivariable regression model examining association between background and pandemic-associated variables, and COVID-19-associated posttraumatic growth in U.S. military veterans.

| Sample characteristics |

Bivariate correlation with moderate or greater PTG |

Multivariable Regression model |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Mean (SD) or N (weighted %) | r | Odds ratio (95%CI) | |

| Background characteristics (R2= 0.16) | |||

| Age | 63.3 (14.7) | 0.01 | – |

| Male gender | 2730 (91.6%) | −0.10*** | 0.52 (0.37–0.71)*** |

| White, non-Hispanic race/ethnicity | 2541 (79.3%) | −0.13*** | 0.69 (0.55–0.87)** |

| College graduate or higher education | 1407 (34.2%) | 0.02 | – |

| Married/partnered | 2220 (74.0%) | −0.01 | – |

| Retired | 1733 (46.8%) | −0.01 | – |

| Household income $60 K+ | 1851 (60.8%) | −0.01 | – |

| Combat veteran | 1051 (35.4%) | −0.03 | – |

| Adverse childhood experiences | 1.4 (1.9) | 0.03 | – |

| Sum lifetime traumas | 8.9 (8.3) | −0.02 | – |

| Psychological distress at Wave 1 | 0 (1.0) | 0.09*** | 0.91 (0.78–1.06) |

| Extraversion | 3.8 (1.5) | 0.08*** | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) |

| Agreeableness | 5.1 (1.2) | 0.09*** | 1.14 (1.04–1.24)** |

| Conscientiousness | 5.8 (1.1) | −0.04* | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) |

| Emotional stability | 5.3 (1.3) | −0.06** | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) |

| Openness to experiences | 4.8 (1.2) | 0.06** | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) |

| Physical health difficulties | 0 (1.0) | 0.09*** | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) |

| Protective psychosocial characteristics | 0 (1.0) | 0.06** | 1.16 (1.01–1.34)* |

| Social connectedness | 0 (1.0) | −0.01 | – |

| Religiosity/spirituality | 0 (1.0) | 0.13*** | 1.20 (1.08–1.32)*** |

| History of mental health treatment | 683 (22.5%) | 0.05** | 0.87 (0.68–1.11) |

| Posttraumatic growth to earlier trauma | 13.9 (12.3) | 0.30*** | 1.04 (1.03–1.05)*** |

| Pandemic-associated factors (R2= 0.32; ΔR2= 0.16) | |||

| COVID infection to self | 233 (8.2%) | −0.03 | – |

| COVID infection to household member | 198 (7.5%) | −0.01 | – |

| COVID infection to non-household member | 1285 (41.4%) | 0.04* | 0.85 (0.70–1.02) |

| Know someone who died of COVID-19 | 177 (5.6%) | 0.06** | 0.94 (0.63–1.39) |

| Daily COVID-19 media consumption | 1.6 (2.1) | 0.13*** | 0.98 (0.94–1.03) |

| COVID-19-associated worries | 0 (1.0) | 0.32*** | 1.96 (1.76–2.18)*** |

| COVID-19-associated social restriction stress | 0 (1.0) | 0.24*** | 1.54 (1.39–1.71)*** |

| COVID-19-associated financial difficulties | 0 (1.0) | 0.12*** | 1.26 (1.14–1.39)*** |

| COVID-19-associated PTSD symptoms | 1.8 (2.6) | 0.29*** | 1.12 (1.07–1.17)*** |

| Changes Since Pre-Pandemic (R2= 0.32; ΔR2= 0.0) | |||

| Traumas since Wave 1 | 1.0 (1.8) | 0.07*** | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) |

| Change in household income | 0 (2.1) | −0.03 | – |

| Change in psychological distress | 0 (0.7) | 0.01 | – |

| Change in protective psychosocial characteristics | 0 (0.7) | −0.02 | – |

| Note: *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001. | |||

Results of a multivariable logistic regression model revealed that background characteristics associated with pandemic-related PTG included female gender, non-White race/ethnicity, agreeableness, protective psychosocial characteristics (post-hoc analysis: purpose in life, OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.01–1.07), religiosity/spirituality, and PTG in relation to earlier trauma (post-hoc analysis: relating to others: OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.05–1.14; new possibilities: OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.05–1.13). Pandemic-related factors associated with PTG included pandemic-related worries (post-hoc analysis: physical health: OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.07–1.38; mental/emotional health: OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.04–1.30), social restriction stress, (post-hoc analysis: stress of changes in family contacts: OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.14–1.48; stress of changes in social contacts: OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.08–1.39); financial difficulties (post-hoc analysis: stability of living situation: OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.15–1.46), and PTSD symptoms, (i.e., avoidance: OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.13–1.36).

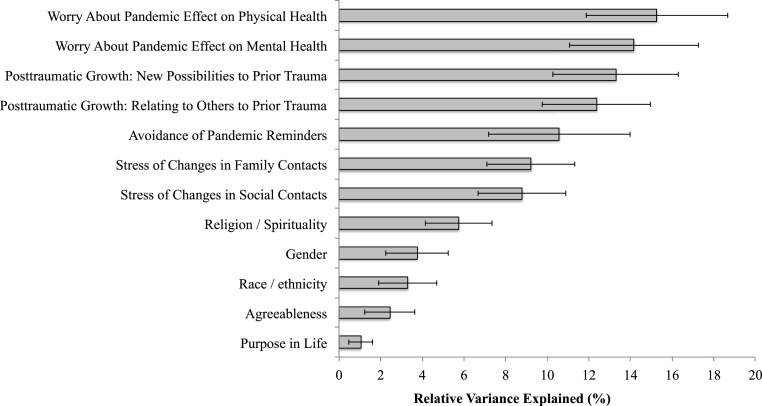

Fig. 1 shows results of a relative importance analysis of factors associated with pandemic-related PTG. Greater worries about the effect of the pandemic on one's physical (15.3% relative variance explained [RVE]) and mental health (14.2% RVE); greater PTG in the form of new possibilities (13.3% RVE) and improved relationships with others (12.4%) related to pre-pandemic traumatic events; greater avoidance symptoms related to the pandemic (10.6% RVE); and greater stress of changes in family (9.2% RVE) and social (8.8% RVE) contacts explained the majority (>80%) of variance in pandemic-related PTG.

Fig. 1.

Results of relative importance analysis of factors associated with pandemic-related posttraumatic growth in U.S. military veterans.

Results of a curve estimation analysis of the relation between severity of pandemic-related PTSD symptoms and probability of endorsing PTG revealed that a quadratic, inverted-U shaped function provided a better fit to the data than a linear function (β = −0.32, t = 8.82, p < 0.001; R 2 quadratic = 0.33 vs. R 2 linear = 0.31). Further, results of ROC curve analyses indicated that a score of 3 on the 4-item PCL-5, which is lower than the cut score of 5 used to identify positive screen for PTSD (sensitivity = 0.41, specificity = 0.82; positive likelihood ratio: 2.32, 95% CI = 2.05–2.61) and that a score of 2 (i.e., moderate severity) of avoidance symptoms (sensitivity = 0.29, specificity = 0.88; positive likelihood ratio: 2.35, 95% CI = 2.02–2.73) were optimally efficient in differentiating veterans who endorsed PTG.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine factors associated with PTG during the COVID-19 pandemic in a nationally representative sample of U.S. military veterans. Results highlight that among a broad range of clinical and psychosocial factors, worries about the effect of the pandemic on one's physical and mental health, PTG in response to pre-pandemic traumatic life events, and greater severity of pandemic-related avoidance symptoms were the strongest correlates of pandemic-related PTG. Further, pandemic-related social restriction stress, most notably stress of changes in family and social contacts, were additionally strongly linked to PTG.

Worries about the effect of the pandemic on one's physical and mental health explained the most variance in pandemic-related PTG. This finding parallels a recent online survey of 805 US young adults, which similarly found that greater COVID-19-related worries were positively associated with PTG during the pandemic (Hyun et al., 2021). However, another cross-sectional survey in Portugal and the UK conducted during the pandemic found no differences in anxiety symptoms between those who did and did not report PTG (Stallard et al., 2021). Nevertheless, our finding is consistent with prior studies suggesting that psychological distress may help spur the process of PTG (Kleim and Ehlers, 2009; Sattler et al., 2014; Sigveland et al., 2012), with greater levels of PTG occurring among individuals with at least moderate levels of distress. In support of this notion, our prior study of this cohort revealed markedly higher prevalence of PTG among veterans who screened positive for pandemic-related PTSD symptoms (Pietrzak et al., 2021). Further, post-hoc analyses revealed that reporting being “very” or “extremely” worried about the effect of the pandemic on one's physical and mental health were associated with the highest probability of reporting pandemic-related PTG (>55% and >65%, respectively). This finding may, at least in part, be explained by PTG reflecting dysfunctional attempts to cope with stressful events (Boerner et al., 2017). Indeed, a recent study found that among individuals who experienced high levels of PTG during the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately one-third reported higher COVID-19-related functional impairment and worsening distress (Asmundson et al., 2021). Another interpretation of this finding is that greater worries related to how the pandemic might affect one's health may have led to more deliberate, organized, and controlled rumination about the pandemic. Indeed, prior work has suggested that deliberate rumination, often in conjunction with a strong social support system, can help foster PTG (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 2004).

Another noteworthy finding of this study is that veterans who reported greater PTG in relation to prior, pre-pandemic traumatic life events were more likely to show PTG in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to find that PTG in response to earlier life traumas—specifically perceiving new possibilities for one's life and improved interpersonal relationships—may help foster PTG to a subsequent trauma. It also extends our previous finding showing that greater PTG—specifically perceptions of personal strength in response to earlier life traumas—may help promote resilience to subsequent traumatic events (Tsai et al., 2016). Veterans who endorsed PTG in relation to pre-pandemic traumas may have a personality style characterized by a greater ability to persevere, solicit support, and grow in response to stressful life events, and may be more likely to employ adaptive coping strategies that may help promote PTG and overall adaptation to the COVID-19 pandemic (Connor and Flachsbart, 2007; Haas, 2015; Seery et al., 2010). Greater wisdom has also been found to buffer the deleterious effect of adverse life events on well-being in older adults (Ardelt and Jeste, 2018).

Avoidance symptoms of PTSD related to the pandemic also explained a considerable proportion of variance in pandemic-related PTG. This finding parallels previous research suggesting that greater severity of avoidance symptoms may contribute to and maintain PTG over time in veterans (Whealin et al., 2020), as well as civilians (Hall et al., 2015; Lowe et al., 2013). It is important to note that avoidance symptoms are one of the core symptoms of PTSD (i.e., avoidance of distressing trauma-related information, thoughts, and feelings, as well as external reminders), and strongly associated with high stress and worse prognosis (Perkonigg et al., 2005). Thus, this finding is consistent with prior research suggesting that the relationship between distress and PTG as a curvilinear and inverted U-shaped, with moderate levels of PTSD symptoms associated with higher levels of PTG (Kleim and Ehlers, 2009; Tsai et al., 2015; Whealin et al., 2020). Indeed, in the current study, a quadratic, inverted U-shaped association was found to best characterize the association between pandemic-related PTSD symptoms and probability of endorsing PTG. Further, a score of 3 on the 4-item PCL-5 and 2 on the avoidance item, which are indicative of moderate severity of PTSD symptoms, were optimally efficient in identifying veterans who endorsed PTG. Of note, this association may also partly reflect engagement in dysfunctional coping strategies such as avoidant coping skills (Boerner et al., 2017) or illusory aspects of PTG (Asmundson et al., 2021). Further longitudinal studies that examine functional correlates of PTG would be helpful in determining the potential constructive/adaptive utility of PTG.

Social restriction stress related to changes in family contacts and social contacts also explained a considerable proportion of variance in pandemic-related PTG. Veterans who have experienced heightened stress due to social restrictions may have gained more appreciation of interpersonal relationships, one of the core domains of PTG, which may have in turn contributed to their being more likely to report pandemic-related PTG. It is possible that veterans with greater social stressors during the pandemic may have been more likely to engage with loved ones using alternative modalities of connecting (e.g., virtual platforms, telephone, texting), which may have helped them process their thoughts and experiences related to the pandemic in a supportive context. Many of the other correlates of pandemic-related PTG identified in the current study (e.g., religiosity/spirituality), each of which explained substantially less variance than the factors noted above, are similar to those identified in prior studies of PTG (Gallaway et al., 2011; Kalaitzaki, 2021; Kleim and Ehlers, 2009; Vishnevsky et al., 2010).

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, while nationally representative, the sample was comprised predominantly of older, male, and White veterans, which makes it difficult to generalize results to more diverse samples of veterans, as well as non-veteran populations. Second, we employed self-report screening instruments to assess all measures. Further research using structured clinical interviews is needed to replicate the results reported herein. Third, although this was a prospective cohort study, given the cross-sectional nature of the surveys and limited follow-up time frame, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding temporal/causal associations between identified correlates of PTG, whether PTG will be maintained over time, or whether PTG reflects real/constructive or illusory growth. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine these questions. Fourth, the PTGI-SF, which was used to assess pandemic-related PTG in the current study, does not allow one to assess PTG depreciation or negative changes that may happen after a trauma (Cann et al., 2010; Taku et al., 2021). Lastly, PTG was assessed dichotomously due to the zero-inflated, non-normal, and positively skewed distribution of PTGI-SF scores. Further research is needed to evaluate the full range of both positive and negative psychological changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic using an assessment scale that captures the entire spectrum of PTG.

5. Conclusion

This is the first known study to examine factors associated with pandemic-related PTG in a population-based sample of U.S. military veterans. Results suggest that health-related worries, PTG in response to pre-pandemic traumas, and avoidance symptoms explained the majority of the variance in pandemic-related PTG. The results underscore the importance of assessing both adverse and salutogenic psychological effects of the pandemic, and of evaluating the potential efficacy of psychosocial interventions to help promote PTG (Roepke, 2015). Further research is needed to replicate and extend these results to other high-risk populations; identify mechanisms leading to increased PTG during the pandemic; and evaluate the efficacy of interventions to help promote PTG.

Author statement

Peter J. Na assisted with the conceptualization, study design, and writing of the paper. Jack Tsai and Steven M. Southwick collaborated in the writing and editing of the manuscript. Robert H. Pietrzak designed the study, analyzed the data, and collaborated in the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

The National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Footnotes

Prepared for: Social Science and Medicine (Section: Research Paper).

References

- Amstadter A.B., Begle A.M., Cisler J.M., Hernandez M.A., Muzzy W., Acierno R. Prevalence and correlates of poor self-rated health in the United States: the national elder mistreatment study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2011;18:615–623. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ca7ef2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F.B., Anderson R.N. The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2021;325(18):1829–1830. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelt M., Jeste D.V. Wisdom and hard times: the ameliorating effect of wisdom on the negative association between adverse life events and well-being. J Geront B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73:1374–1383. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson G.J.G., Paluszek M.M., Taylor S. Real versus illusory personal growth in response to COVID-19 pandemic stressors. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021;81:102418. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner M., Joseph S., Murphy D. A theory of reports of constructive (real) and illusory posttraumatic growth. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2017;60:384–399. [Google Scholar]

- Bostock L., Sheikh A.I., Barton S. Posttraumatic growth and optimism in health-related trauma: a systematic review. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 2009;16:281–296. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J., Finucane M.L., Locker A.R., Baird M.D., Roth E.A., Collins R.L. A longitudinal study of psychological distress in the United States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Med. 2021;143:106362. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann A., Calhoun L.G., Tedeschi R.G., Taku K., Vishnevsky T., Triplett K.N., et al. A short form of the posttraumatic growth inventory. Hist. Philos. Logic. 2010;23:127–137. doi: 10.1080/10615800903094273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L., Stein M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma Stress. 2007;20:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi X., Becker B., Yu Q., Willeit P., Jiao C., Huang L., et al. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of mental health outcomes among Chinese college students during the corona virus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Front. Psychiatr. 2020;11:803. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J.K., Flachsbart C. Relations between personality and coping: a meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007;93:1080–1107. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler M.E., Lane R.I., Petrosky E., Wiley J.F., Christensen A., Njai R., et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69:1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettman C.K., Abdalla S.M., Cohen G.H., Sampson L., Vivier P.M., Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder A., Southwick S.M., Goetz R.R., Wang Y., Alonso A., Smith B.W., et al. Posttraumatic growth in former Vietnam prisoners of war. Psychiatry. 2008;71:359–370. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D.F., Spitz A.M., Edwards V., Koss M.P., Marks J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstmeier S., Kuwert P., Spitzer C., Freyberger H.J., Maercker A. Posttraumatic growth, social acknowledgment as survivors, and sense of coherence in former German child soldiers of World War II. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2009;17:1030–1039. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ab8b36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallaway M.S., Millikan A.M., Bell M.R. The association between deployment-related posttraumatic growth among U.S. Army soldiers and negative behavioral health conditions. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011;67:1151–1160. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier T., Hunt J.C., Hanson J.L., Heyrman K., Larsen S.E., Brael K.J., Deroon-Cassini T.A. Validation of abbreviated four- and eight-item versions of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 in a traumatically injured sample. J. Trauma Stress. 2020;33:218–226. doi: 10.1002/jts.22478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling S.D., Rentfrow P.J., Swann W.B., Jr. A very brief measure of the big five personality domains. J. Res. Pers. 2003;37:504–528. [Google Scholar]

- Haas M. 2015. Bouncing Forward: Transforming Bad Breaks into Breakthroughs Atria/Enliven. [Google Scholar]

- Hafstad G.S., Kilmer R.P., Gil-Rivas V. Posttraumatic adjustment and posttraumatic growth among Norwegian children and adolescents to the 2004 Tsunami. Psychol Trauma. 2011;3:130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hall B.J., Saltzman L.Y., Canetti D., Hobfoll S.E. A longitudinal investigation of the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and posttraumatic growth in a cohort of Israeli Jews and Palestinians during ongoing violence. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamam A.A., Milo S., Mor I., Shaked E., Eliav A.S., Lahav Y. Peritraumatic reactions during the COVID-19 pandemic - the contribution of posttraumatic growth attributed to prior trauma. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;132 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C., Shaver P.R. Love and work: an attachment-theoretical perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990;59:270–280. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson V.S., Reynolds K.A., Tomich P.L. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006;74:797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M.L., Nichter B., Na P.J., Norman S.B., Morland L.A., Krystal J., et al. 2021. Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in U.S. Military Veterans: A Population-Based, Prospective Cohort Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun S., Wong G.T.F., Levy-Carrick N.C., Charmaraman L., Cozier Y., Yip T., et al. Psychosocial correlates of posttraumatic growth among US young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;302:114035. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzaki A. 2021. Posttraumatic Symptoms, Posttraumatic Growth, and Internal Resources Among the General Population in Greece: A Nation-wide Survey amid the First COVID-19 Lockdown. Int J Psychol. (Online ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan T.B., Gallagher M.W., Silvia P.J., Winterstein B.P., Breen W.E., Terhar D., Steger M.F. The curiosity and exploration inventory-II: development, factor structure, and psychometrics. J. Res. Pers. 2009;43:987–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim B., Ehlers A. Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between posttraumatic growth and posttrauma depression and PTSD in assault survivors. J. Trauma Stress. 2009;22:45–52. doi: 10.1002/jts.20378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliouli F., Canellopoulos L. Dispositional optimism, stress, post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth in Greek general population facing the COVID-19 crisis. Eur J Trauma Dissoc. 2021;5:100209. doi: 10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H.G., Bussing A. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions. 2010;1:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy Y., Nagarajan R., Saya G.K., Menon V. Prevalence of psychoogical morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;293:113382. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav Y. Psychological distress related to COVID-19 – the contribution of continuous traumatic stress. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer A., Solomon Z. Posttraumatic symptoms and posttraumatic growth among Israeli youth exposed to terror incidents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2006;25:429–447. [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Luo S., Mu W., Li Y., Ye L., Zheng X., et al. Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatr. 2021;21:16. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-03012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Mao M., Wang S., Yin R., Yan H., Jin Y., et al. Posttraumatic growth in Chinese nurses and general public during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol. Health Med. 2021 doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1897148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linley P.A., Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review. J. Trauma Stress. 2004;17:11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe S.R., Manove E.E., Rhodes J.E. Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth among low-income mothers who survived Hurricane Katrina. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013;81:877–889. doi: 10.1037/a0033252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini C.M., Kaiser A.P., Smith B.N., Fiori K.L. Aging veterans' mental health and well-being in the context of COVID-19: the importance of social ties during physical distancing. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S217–S219. doi: 10.1037/tra0000736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough M.E., Emmons R.A., Tsang J. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002;82:112–127. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen J.C., Smith E.M., Fisher R.H. Perceived benefit and mental health after three types of disaster. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997;65:733–739. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M.M., Gallaway M.S., Millikan A.M., Bell M.R. Combat exposure, unit cohesion, and demographic characteristics of soldiers reporting posttraumatic growth. J. Loss Trauma. 2013;18:383–395. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J.K., Desmarais S.L., Mitchell R.E., Simons-Rudolph J.M. Posttraumatic stress, posttraumatic growth, and satisfaction with life in military veterans. Mil. Psychol. 2017;29:434–447. [Google Scholar]

- Morrill E.F., Brewer N.T., O'Neill S.C., Lillie S.E., Dees E.C., Carey L.A., et al. The interaction of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress symptoms in predicting depressive symptoms and quality of life. Psycho Oncol. 2008;17:948–953. doi: 10.1002/pon.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na P.J., Norman S.B., Nichter B., Hill M.L., Rosen M.I., Petrakis I.L., et al. Prevalence, risk and protective factors of alcohol use disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in U.S. military veterans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;225:108818. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na P.J., Tsai J., Hill M.L., Nichter B., Norman S.B., Southwick S.M., et al. Prevalence, risk and protective factors associated with suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic in US military veterans with pre-existing psychiatric conditions. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;137:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program Mood Spectrum Collaboration, & Child Mind Institute of the NYS Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research . 2020. The CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey (CRISIS) [Google Scholar]

- Nichter B., Hill M.L., Na P.J., Kline A.C., Norman S.B., Krystal J.H., et al. Prevalence and trends in suicidal behavior among US military veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2332. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick J.H., Henrie J. Up from the ashes: age and gender effects on post-traumatic growth in bereavement. Women Ther. 2016;39:296–314. [Google Scholar]

- Perkonigg A., Pfister H., Stein M.B., Hoefler M., Lieb R., Maercker A., Wittchen H.-U. Longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2005;162:1320–1327. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak R.H., Goldestein M.B., Malley J.C., Rivers A.J., Johnson D.C., Morgan C.A., et al. Posttraumatic growth in veterans of operations enduring freedom and Iraqi freedom. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;126:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak R.H., Tsai J., Southwick S.M. Association of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder with posttraumatic psychological growth among US veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkis J., John A., Shin S., DelPozo-Banos M., Arya V., Analuisa-Anguilar P., et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry, Published. 2021;8(7):579–588. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothisiri W., Vicerra P.M.M. Psychological distress during COVID-19 pandemic in low-income and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study of older persons in Thailand. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell S., Rosner R., Butollow W., Tedeschi R.G., Calhoun L.G. Posttraumatic growth after war: a study with former refugees and displaced people in Sarajevo. J. Clin. Psychol. 2003;59:71–83. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati G., Pietrantoni L. Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: a meta-analysis. J. Loss Trauma. 2009;14:364–388. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Ursua M., Jodar R. Finding meaning in hell. The role of meaning, religiosity and spirituality in posttraumatic growth during the coronavirus crisis in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:567836. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger M.A., Stanley I.H., Joiner T.E. Suicide mortality and corona virus disease 2019 - a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:1093–1094. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepke A.M. Psychosocial interventions and posttraumatic growth: a meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015;83:129–142. doi: 10.1037/a0036872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler D.N., Bloyd B., Kirsch J. Trauma-exposed Firefighters: relationships among posttraumatic growth, posttraumatic stress, resource availability, coping and critical incident stress debriefing experience. Stress Health. 2014;30:356–365. doi: 10.1002/smi.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier M.F., Carver C.S., Bridges M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seery M.D., Holman E.A., Silver R.C. Whatever does not kill us: cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability, and resilience. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010;99:1025–1041. doi: 10.1037/a0021344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbournce C.D., Stewart A.L. The MOS social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigveland J., Hafstad G.S., Tedeschi R.G. Posttraumatic growth in parents after a natural disaster. J. Loss Trauma. 2012;17:536–544. [Google Scholar]

- Stallard P., Pereira A.I., Barros L. Post-traumatic growth during the COVID-19 pandemic in carers of children in Portugal and the UK: cross-sectional online survey. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:1–5. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taku K., Tedeschi R.G., Shakespeare-Finch J., Krosch D., David G., Kehl D., et al. Posttraumatic growth (PTG) and posttraumatic depreciation (PTD) across ten countries: global validation of the PTG-PTD theoretical model. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2021;169:110222. [Google Scholar]

- Tamiolaki A., Kalaitzaki A.E. “That which does not kill us, makes us stronger”: COVID-19 and posttraumatic growth. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;289:113044. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R.G., Calhoun L.G. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004;15:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tonidandel S., LeBreton J.M. Determining the relative importance of predictors in logistic regression: an extension of relative weights analysis. Organ. Res. Methods. 2010;13:767–781. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J., El-Gabalawy R., Sledge W.H., Southwick S.M., Pietrzak R.H. Post-traumatic growth among veterans in the USA: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Psychol. Med. 2015;45:165–179. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J., Huang M., Elbogen E. Psychiatr Serv; 2021. Mental Health and Psychosocial Characteristics Associated with COVID-19 Among US Adults. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J., Mota N.P., Southwick S.M., Pietrzak R.H. What doesn't kill you makes you stronger: a national study of U.S. military veterans. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;189:269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez C., Valiente C., Garcia F.E., Contreras A., Peinado V., Trucharte A., et al. Post-traumatic growth and stress-related responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in a national representative sample: the role of positive core beliefs about the world and others. J. Happiness Stud. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00352-3. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishnevsky T., Cann A., Calhoun L.G., Tedeschi R.G., Demakis G.J. Gender differences in self-reported posttraumatic growth: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Women Q. 2010;34:110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F., Litz B., Keane T., Palmieri P., Marx B., Schnurr P. 2013. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5.http://www.ptsd.va.gov (PCL-5) [Online]. Available: Scale available at: from the National Center for PTSD at. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F., Blake D.D., Schnurr P.P., Kaloupek D.G., Marx B.P., Keane T.M. 2013. The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5.www.ptsd.va.gov (LEC-5). Instrument available from: the National Center for PTSD at. [Online] [Google Scholar]

- Whealin J.M., Pitts B., Tsai J., Rivera C., Fogle B.M., Southwick S.M., et al. Dynamic interplay between PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth in older military veterans. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;269:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Kaminga A.C., Dai W., Deng J., Wang Z., Pan X., Liu A. The prevalence of moderate-to-high posttraumatic growth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;243:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Hu M.-L., Song Y., Lu Z.-X., Chen Y.-Q., Wu D.-X., et al. Effect of positive psychological intervention on posttraumatic growth among primary healthcare workers in China: a preliminary prospective study. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:39189. doi: 10.1038/srep39189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz E. Posttraumatic growth and positive determinants in nursing students after COVID-19 alarm status: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Psychiatr. Care. 2021 doi: 10.1111/ppc.12761. (Online ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Li M., Li Z., Xiang W., Yuan Y., Liu Y., et al. Coping style, social support and psychological distress in the general Chinese population in the early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic. BMC Psychiatr. 2020;20:426. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02826-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai H.-K., Li Q., Hu Y.-X., Cui Y.-X., Wei X.-W., Zhou X. Emotional creativity improves posttraumatic growth and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:600798. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.600798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner T., Maercker A. Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology – a critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006;26:626–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]