Abstract

Background:

When meniscal repair is performed during anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction (ACLR), the effect of ACL graft type on meniscal repair outcomes is unclear.

Hypothesis:

The authors hypothesized that meniscal repairs would fail at the lowest rate when concomitant ACLR was performed with bone--patellar tendon--bone (BTB) autograft.

Study Design:

Cohort study; Level of evidence, 3.

Methods:

Patients who underwent meniscal repair at primary ACLR were identified from a longitudinal, prospective cohort. Meniscal repair failures, defined as any subsequent surgical procedure addressing the meniscus, were identified. A logistic regression model was built to assess the association of graft type, patient-specific factors, baseline Marx activity rating score, and meniscal repair location (medial or lateral) with repair failure at 6-year follow-up.

Results:

A total of 646 patients were included. Grafts used included BTB autograft (55.7%), soft tissue autograft (33.9%), and various allografts (10.4%). We identified 101 patients (15.6%) with a documented meniscal repair failure. Failure occurred in 74 of 420 (17.6%) isolated medial meniscal repairs, 15 of 187 (8%) isolated lateral meniscal repairs, and 12 of 39 (30.7%) of combined medial and lateral meniscal repairs. Meniscal repair failure occurred in 13.9% of patients with BTB autografts, 17.4% of patients with soft tissue autografts, and 19.4% of patients with allografts. The odds of failure within 6 years of index surgery were increased more than 2-fold with allograft versus BTB autograft (odds ratio = 2.34 [95% confidence interval, 1.12-4.92]; P = .02). There was a trend toward increased meniscal repair failures with soft tissue versus BTB autografts (odds ratio = 1.41 [95% confidence interval, 0.87-2.30]; P = .17). The odds of failure were 68% higher with medial versus lateral repairs (P < .001). There was a significant relationship between baseline Marx activity level and the risk of subsequent meniscal repair failure; patients with either very low (0-1 points) or very high (15-16 points) baseline activity levels were at the highest risk (P = .004).

Conclusion:

Meniscal repair location (medial vs lateral) and baseline activity level were the main drivers of meniscal repair outcomes. Graft type was ranked third, demonstrating that meniscal repairs performed with allograft were 2.3 times more likely to fail compared with BTB autograft. There was no significant difference in failure rates between BTB versus soft tissue autografts.

Registration:

NCT00463099 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier).

Keywords: meniscal repair, ACL reconstruction, autograft, allograft

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures are frequently accompanied by a meniscal tear.7,38,53 Depending on their type, size, and location, some meniscal tears are amenable to repair at the time of ACL reconstruction (ACLR). A recent large-scale, prospective study reported meniscal tears in 66% of patients undergoing primary ACLR and 30% of these patients were treated with concomitant meniscal repair.54 Over the past few decades, the rate at which meniscal repair is performed at the time of ACLR has continued to grow1 partly because of advancements in arthroscopic meniscal repair techniques.

Meniscectomy increases the risk of developing knee osteoarthritis.15,41 This observation gives reason to believe that meniscal repair leads to better clinical outcomes than does meniscectomy. However, this conclusion cannot be drawn from results in the literature. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that patients who undergo ACLR with concomitant meniscal resection demonstrate better outcomes at 2-year follow-up compared with those who undergo ACLR combined with meniscal repair.43 Although lateral meniscectomy has been found to decrease lateral compartment joint space width significantly, lateral meniscal repair does not appear to pose the same risk.21 Conversely, repair and excision of medial meniscal tears have been identified as predictors for radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis in the medial compartment.22 Likewise, inferior patient-reported outcomes and an increased risk of reoperation have been associated with medial but not lateral meniscal repairs as compared with isolated ACLRs without concomitant meniscal pathology.5,11

In the setting of an acute ACL injury, lateral meniscal tears are more commonly encountered than are medial meniscal tears.4,45,48 Yet, the incidence of medial meniscal repair at the time of ACLR is twice as high as that of lateral repair.48,54 In 235 patients who underwent meniscal repair at the time of ACLR, no significant difference in failure rate was identified between medial (13.6%) and lateral (13.9%) repairs. However, the average time to failure was significantly shorter in patients with medial (2.1 ± 1.6 years) versus lateral (3.7 ± 1.3 years) meniscal repair.54

ACL graft type has not been examined previously as a risk factor for meniscal repair failure. To this end, the purpose of this study was to examine the influence of ACL graft type on the outcome of meniscal repairs performed at the time of ACLR. We hypothesized that meniscal repairs performed at the time of ACLR with bone--patellar tendon--bone (BTB) autografts would fail at a lower rate than would those performed with allografts or soft tissue autografts.

Methods

Setting and Study Population

The Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) is a prospective, longitudinal cohort that has followed ACLRs performed at 7 institutions (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee; Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio; The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio; University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa; Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri; Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, New York; and University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado) since 2002. Institutional review board approval was obtained by each participating site before beginning patient enrollment. One university operated as the data processing center and was responsible for collecting and entering baseline and follow-up data on all patients. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00463099). The methodology of patient enrollment and data collection for this cohort has been described in detail previously.11,20

This study was a retrospective review and analysis of the abovementioned prospectively collected data. The inclusion criterion for this study was meniscal repair at the time of ACLR. Revision cases and those performed with a hybrid ACL graft were excluded. Failure of meniscal repair was defined as any subsequent surgical procedure addressing the meniscus repaired at index surgery. This is consistent with its definition in studies published previously reporting meniscal repair outcomes.1,28,54 After identifying patients with subsequent meniscal surgery, operative notes were reviewed to accurately classify pathology and treatment of meniscal reinjuries.

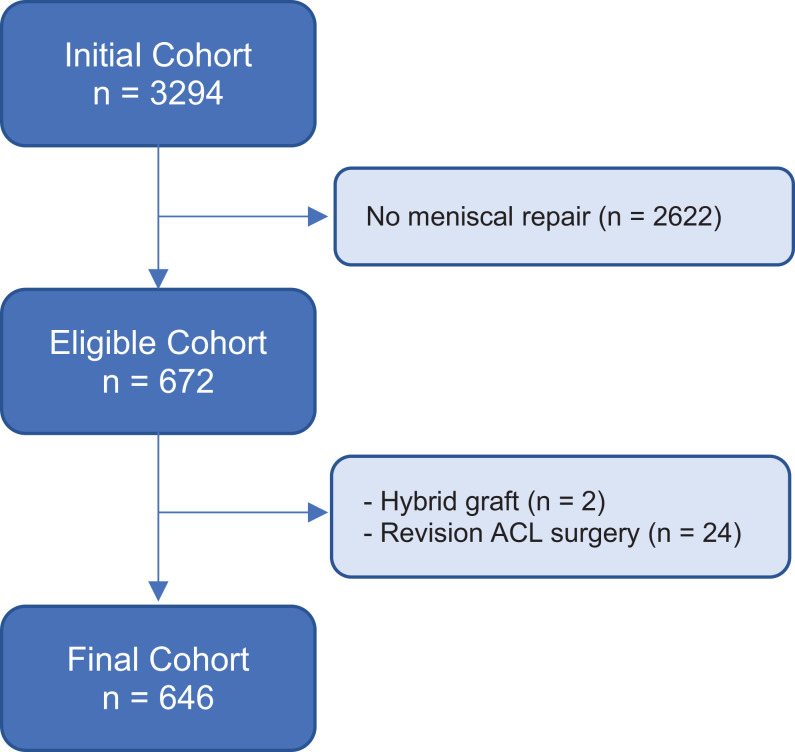

A total of 3294 participants underwent ACLR between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2008, and were initially enrolled as part of the longitudinal prospective cohort study. A concomitant meniscal repair was performed in 672 (20.4%) patients, and 2622 patients were excluded owing to no meniscal repair. An additional 26 patients were excluded because they had revision ACLRs or a hybrid ACL graft (24 with revision ACLR and 2 with autograft-allograft hybrid ACL grafts). The remaining 646 patients were included in our analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient enrollment. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

Data Sources and Measurement

After informed consent was obtained, we asked all patients to complete a 13-page questionnaire inquiring about baseline characteristic information, injury descriptors, and validated patient-reported outcome measures including the Marx activity rating scale.32 Questions from the Marx activity rating scale pertained to the patient’s activity level from the past year. Thus, scores were likely to reflect the patient’s preinjury activity level on a scale from 0 (lowest activity level) to 16 (highest activity level).

Surgeons completed detailed questionnaires at the time of surgery. Documentation included knee laxity during examination under anesthesia prior to ACLR, surgical technique, graft type, and arthroscopic findings and treatment of meniscal injuries. Meniscal injuries were classified by size, location, and partial versus complete tears, whereas treatment was recorded as not treated, repair, or extent of resection.14 Interrater reliability among included surgeons’ classification and treatment of meniscal pathology has been established previously.14 Postoperatively, patients were given a uniform set of standardized, evidence-based rehabilitation guidelines.55

All participating sites mailed completed data forms to the data processing center. Questionnaires (patient and surgeon forms) were scanned via Teleform software (OpenText) using optical character recognition. After data in the scanned forms were verified, they were exported to a master database and checked using a series of logical error and quality control tests. In cases where checks failed, verification against source documents was carried out to ensure accuracy prior to data analysis.

Follow-up

The same questionnaire that patients completed at baseline (defined as the time of index ACL surgery) was readministered and returned via mail at 2- and 6-year follow-up. All patients were also contacted to determine whether they had undergone any additional surgical knee procedures since the time of index surgery. In cases in which an additional surgical knee procedure was reported, every effort was made to obtain the corresponding operative report. Follow-up was managed at the designated data processing center. In addition, surgeon investigators and/or their respective sites assisted in contacting patients to achieve and maintain a high level of follow-up.

Of the 646 patients who initially had a meniscal repair done at the time of their index ACLR, 586 patients (91%) were available for follow-up. The remaining 9% were lost to follow-up (7.6%, unable to reach; 1%, refused; <1%, incarcerated; <1%, deceased).

Statistical Analysis

Description of the cohort was performed using counts and percentages for categorical data (sex, ACL graft type, meniscal repair location, and the occurrence of meniscal repair failure). The median value and interquartile range (IQR) were reported when describing numerical data (age, body mass index [BMI], and baseline Marx activity level). A logistic regression model was built to assess the association of ACL graft with the occurrence of meniscal repair failure 6 years following index surgery. Age, sex, BMI, baseline Marx activity level,32 and meniscal repair location (medial or lateral) were evaluated as possible confounding or effect-modifying variables. Any missing baseline data were singly imputed using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations.51 For numerical variables (age, BMI, Marx activity level), odds ratios (ORs) were computed by comparing the 25th percentile relative to the 75th percentile. Statistically significant results from the logistic regression model were determined using 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that did not include the null value (1). To analyze the relative contribution of individual predictors, the amount of decrease in bootstrap-validated concordance probability (C-index) was evaluated upon removal of each covariate from the full model. All statistical analyses were performed using R open-source statistical software (Version 3.4; R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the studied cohort. The study population was composed of 365 male patients (56.5%) and 281 female patients (43.5%). The median age was 20 years at the time of index surgery. The medial meniscus was repaired in 420 patients (65%), and the lateral meniscus was repaired in 187 patients (29%). A total of 39 patients (6%) underwent repair of both the medial and the lateral menisci at the time of ACLR. ACL graft choice comprised 360 (56%) BTB autografts, 219 (34%) soft tissue autografts, and 67 (10%) allografts. Of the 219 soft tissue autografts, 218 were hamstring (159 semitendinosus and gracilis; 59 semitendinosus), and 1 was an iliotibial band over-the-top procedure for a pubescent male patient. Of the 67 allografts used, 22 were BTB, 36 were anterior/posterior tibialis, 8 were Achilles tendon, and 1 was a combination hamstring (semitendinosus and gracilis) plus tibialis graft. The allografts in this study were predominantly fresh frozen, without proprietary processing, and were nonirradiated or irradiated <2.5 mRad.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics and Surgical Detailsa

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 20 (16, 28) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 281 (43.5) |

| Male | 365 (56.5) |

| BMI | 24 (22, 27) |

| Missing/not reported | 11 (2) |

| Marx activity level (0–16) | 14 (9, 16) |

| Missing/not reported | 4 (1) |

| ACL graft | |

| BTB autograft | 360 (56) |

| Soft tissue autograft | 219 (34) |

| Allograft | 67 (10) |

| Meniscal repair location | |

| Medial | 420 (65) |

| Lateral | 187 (29) |

| Both | 39 (6) |

aData are reported as median (25%, 75% quartiles) for numeric variables and counts (%) for categorical variables and number of participants with missing data. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; BMI, body mass index; BTB, bone--patellar tendon--bone.

Outcomes at 6-Year Follow-up

We identified 101 patients (15.6%) with a documented meniscal repair failure. Revision meniscal surgeries included 89 partial meniscectomies, 11 revision meniscal repairs, and 1 meniscal allograft transplantation. Of the 101 revision meniscal surgeries, 77 were for isolated meniscal pathology, and the remaining 24 were performed at the time of revision ACLR (Table 2). Among the 24 failed ACL grafts, 12 were soft tissue autografts (50%), 9 were BTB autografts (37.5%), and 3 were allografts (12.5%). In patients who underwent repair of only the medial or lateral meniscus, a documented failure was identified in 74 of 420 medial repairs (17.6%) compared with 15 of 187 (8.0%) lateral repairs. A total of 39 patients underwent repair of both the medial and the lateral menisci, 12 (30.7%) of whom required subsequent meniscal surgery. Of these, the medial repair failed in 7 patients (58.3%), the lateral repair failed in 1 patient (8.3%), and both medial and lateral repairs failed in 4 patients (33.3%).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Meniscal Repair Failure Stratified by Concomitant Revision ACL Reconstructiona

| Variable | Isolated Meniscal Repair Failure (n = 77) | Failure of Meniscal Repair and ACL Graft (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 19 (16.5, 27.5) | 16.5 (15, 18) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 38 (49.4) | 9 (37.5) |

| Male | 39 (50.6) | 15 (62.5) |

| BMI | 24.4 (22, 26) | 23.2 (20, 26) |

| Marx activity level (0–16) | 16 (14, 16) | 16 (12, 16) |

| ACL graft type | ||

| BTB autograft | 41 (53.2) | 9 (37.5) |

| Soft tissue autograft | 26 (33.8) | 12 (50) |

| Allograft | 10 (13) | 3 (12.5) |

| Side of meniscal repair | ||

| Medial | 61 (79) | 13 (54) |

| Lateral | 6 (8) | 9 (38) |

| Both | 10 (13) | 2 (8) |

| Side of revision meniscal surgery | ||

| Medial | 7 (70) | 0 (0) |

| Lateral | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Both | 2 (20) | 2 (100) |

aData are reported as median (25%, 75% quartiles) for numeric variables and counts (%) for categorical variables. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; BMI, body mass index; BTB, bone--patellar tendon—bone.

Table 3 summarizes the morphology of all meniscal tears and the surgical technique employed at index surgery. The surgical technique employed for ACLR among our cohort is summarized in Table 4. Theoretically, the percentage of the cohort should equal the expected percentage of the number of meniscal failures. Based on a post hoc chi-square analysis, no significant differences were found in surgical technique (P = .59), femoral fixation (P = .86), or tibial fixation (P = .39).

Table 3.

Summary of Meniscal Tear Morphology and Repair Techniquea

| Medial Meniscal Repairs | Lateral Meniscal Repairs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 459) | Failed (n = 86) | Total (n = 226) | Failed (n = 27) | |

| Tear length, mm | 15 (12, 18) | 15 (13, 18) | 15 (12, 20) | 15 (15, 20) |

| Tear pattern | ||||

| Longitudinal | 387 (84) | 73 (19) | 174 (77) | 23 (13) |

| Bucket handle | 55 (12) | 7 (13) | 27 (12) | 2 (7) |

| Oblique | 7 (1.5) | 3 (43) | 9 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Complex | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (3) | 1 (14) |

| Radial | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (33) |

| Horizontal | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (2.2) | 0 (0) |

| NA | 7 (1.5) | 3 (43) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Repair technique | ||||

| All inside | 407 (89) | 78 (19) | 207 (92) | 25 (12) |

| Inside out | 36 (8) | 5 (14) | 15 (7) | 2 (13) |

| Inside out and all inside | 8 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Outside-in | 6 (1.3) | 3 (50) | 4 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| NA | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

aData are reported as median (25%, 75% quartiles) for numeric variables and counts (%) for categorical variables. NA, not available.

Table 4.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Technique

| Meniscal Repairs, n (% of cohort) | Meniscal Failures, n (% of failures) | |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical technique | ||

| 1 incision | 398 (62) | 65 (64) |

| 2 incision | 248 (38) | 36 (36) |

| Total | 646 (100) | 101 (100) |

| Femoral fixation | ||

| Cross pin | 54 (8) | 11 (11) |

| Interference screw | 371 (57) | 53 (52) |

| Interference screw + suture | 3 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Other | 23 (4) | 5 (5) |

| Suture + button/Endobuttona | 190 (29) | 30 (30) |

| Suture + post | 5 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Total | 646 (100) | 101 (100) |

| Tibial fixation | ||

| Combination | 9 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Interference screw | 471 (73) | 69 (69) |

| Interference screw + suture | 9 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Other | 91 (14) | 14 (14) |

| Staple tissue | 12 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Suture + button/Endobuttona | 12 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Suture + post | 42 (7) | 11 (11) |

| Total | 646 (100) | 101 (100) |

aEndobutton manufactured by Smith & Nephew, Inc.

Among the 360 patients who underwent ACLR with a BTB autograft, 50 (13.9%) had a documented meniscal repair failure at 6-year follow-up. The median time to revision meniscal surgery in the BTB autograft group was 22.5 months (IQR, 14.3-40.5 months). A documented meniscal repair failure was identified in 38 of 219 patients (17.4%) with a soft tissue autograft ACLR after a median time of 21.5 months (IQR, 10.6-35.4 months). Finally, of the 67 patients in the allograft ACLR group, 13 (19.4%) were found to have a documented failure of meniscal repair after a median time of 13.1 months (IQR, 6.4-22.7 months). Subgroup analysis of the 622 patients who did not undergo revision ACLR demonstrated that meniscal repair failure occurred in 41 of 351 patients with BTB autografts (11.7%), 26 of 207 patients with soft tissue autografts (12.6%), and 10 of 64 patients with allografts (15.6%). Table 5 stratifies the baseline characteristics of our cohort by ACL graft type and the occurrence of meniscal repair failure.

Table 5.

Baseline Characteristics Stratified by ACL Graft Type and Occurrence of Meniscal Repair Failurea

| BTB Autograft | Soft Tissue Autograft | Allograft | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total (n = 360) |

Success (n = 310) |

Failure (n = 50) |

Total (n = 219) |

Success (n = 181) |

Failure (n = 38) |

Total (n = 67) |

Success (n = 54) |

Failure (n = 13) |

| Age | 18 (16, 26) |

19 (16, 26) |

18 (15, 22) |

22 (16, 28) |

22 (17, 29) |

18.5 (15, 27) |

28 (18, 37) |

28 (22, 38) |

17 (17, 34) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 205 (57) | 178 (87) | 27 (13) | 127 (58) | 105 (83) | 22 (17) | 33 (49) | 28 (85) | 5 (15) |

| Female | 155 (43) | 132 (85) | 23 (15) | 92 (42) | 76 (83) | 16 (17) | 34 (51) | 26 (76) | 8 (24) |

| BMI | 24.4 (22, 27) |

24.4 (22, 27) |

24.4 (22, 25) |

24.4 (22, 27) |

24.4 (22, 27) |

24.7 (22, 27) |

25.8 (23, 31) |

26.6 (23, 31) |

23.0 (20, 29) |

| Missing | 8 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Marx activity level | 15 (9, 16) |

14.5 (9, 16) |

16 (12, 16) |

14 (9, 16) |

13 (9, 16) |

16 (12, 16) |

12 (4, 16) |

9 (4, 13) |

16 (12, 16) |

| Missing | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meniscal repair location | |||||||||

| Medial | 255 (71) | 213 (84) | 42 (16) | 126 (57) | 101 (80) | 25 (20) | 39 (58) | 32 (82) | 7 (18) |

| Lateral | 91 (25) | 87 (96) | 4 (4) | 72 (33) | 65 (90) | 7 (10) | 24 (36) | 20 (83) | 4 (17) |

| Both | 14 (4) | 10 (71) | 4 (29) | 21 (10) | 15 (79) | 6 (21) | 4 (6) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) |

aData are reported as median (25%, 75% quartiles) for numeric variables, counts (%) for categorical variables, and number of participants with missing data (not reported). ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; BMI, body mass index; BTB, bone--patellar tendon--bone.

Patient-Specific Risk Factors

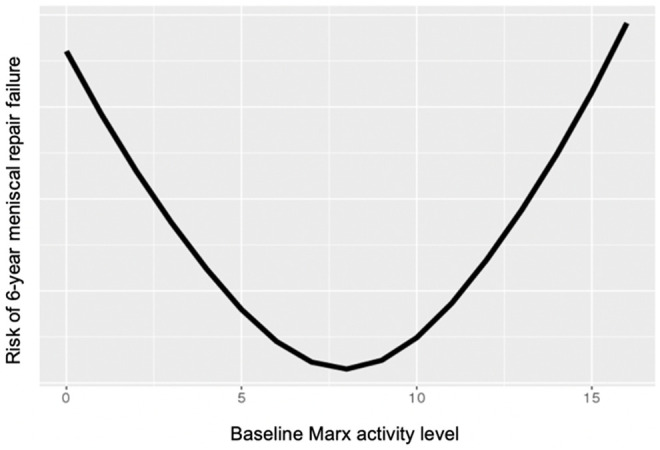

The logistic regression model demonstrated a significant difference in the risk of meniscal repair failure among ACL graft types (Table 6). The odds of meniscal repair failure within 6 years of index surgery for the BTB autograft group were 2.34 times lower than were those of the allograft group (95% CI, 1.12-4.92; P = .02). The odds of failure within 6 years of surgery were 68% less with lateral versus medial repairs (95% CI, 41%-83%; P < .001). We identified a significant, nonlinear relationship between baseline Marx activity level and the risk of meniscal repair failure. That is, patients with low (0-1 points) or high (15-16 points) baseline activity levels were at higher risk of meniscal repair failure compared with patients with midrange (7-9 points) activity levels (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.05-1.31; P = .004 (Figure 2). No significant differences in meniscal repair failure rate were observed based on patient age (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.6-1.3; P = .48), sex (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.6-1.5; P = .69), or BMI (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.6-1.1; P = .13).

Table 6.

Odds of Meniscal Repair Failure as Estimated Using a Logistic Regression Modela

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.87 (0.60-1.27) | .48 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Reference | |

| Female | 0.91 (0.57-1.45) | .69 |

| BMI | 0.80 (0.59-1.07) | .13 |

| Baseline activity level | ||

| Linear | 0.89 (0.79-1.00) | .05 |

| Nonlinear | 1.17 (1.05 -1.31) | .004 |

| ACL graft type | ||

| BTB autograft | Reference | |

| Soft tissue autograft | 1.41 (0.87-2.30) | .17 |

| Allograft | 2.34 (1.12-4.92) | .02 |

| Meniscal repair location | ||

| Medial | Reference | |

| Lateral | 0.32 (0.17-0.59) | <.001 |

| Both | 1.73 (0.80-3.77) | .16 |

aBold values indicate statistical significance. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; BMI, body mass index; BTB, bone--patellar tendon—bone.

Figure 2.

Profile plot of the relationship between baseline Marx activity rating score (range, 0-16 points) and risk of subsequent meniscal repair.

Relative Strength of Association Between Predictor Variables and Failure

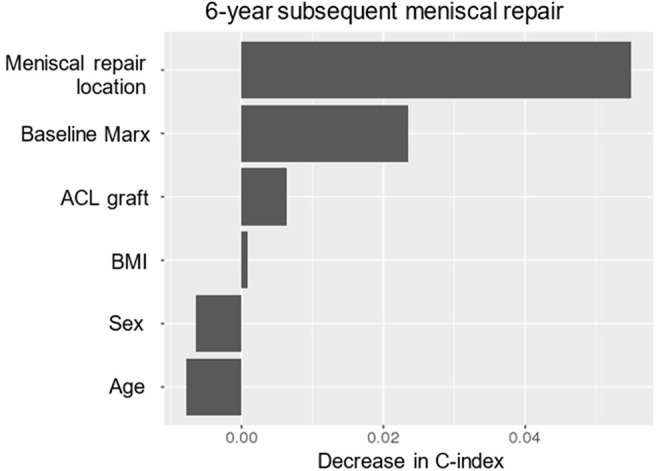

The relative strength of associations between each predictor variable and the risk of meniscal repair failure at 6 years is shown in Figure 3. It was found that meniscal repair location (medial vs lateral) and baseline Marx activity level were the main 2 drivers of the outcome. Of all tested variables, ACL graft type was ranked third, demonstrating predictive ability when included in the model.

Figure 3.

Relative variable importance by the decrease in bootstrap-validated concordance probability (C-index) upon removal from the full model. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

In the setting of meniscal repairs performed concomitantly with ACLR, the risk of subsequent meniscal repair failure may differ based on ACL graft choice. Specifically, the risk of failure may increase >2-fold when ACLR is performed using an allograft compared with a BTB autograft. There was no significant difference in risk of meniscal repair failure between patients who underwent ACLR with BTB and soft tissue autografts. The allografts in this study were predominantly fresh frozen, without proprietary processing, and were nonirradiated or irradiated <2.5 mRad. In a systematic review by Roberson et al,39 it was noted that comparing allograft processing techniques is difficult owing to differences in the various methods and lack of pertinent details when reported in the literature. Nevertheless, the results of our study should be considered when choosing an ACL graft source for patients who have repairable meniscal tears at the time of ACLR, as allografts may lead to an increased risk of meniscal repair failure.

In our series, only 2 patients with allograft-autograft hybrid ACLR and concomitant meniscal repair were identified. These patients were excluded from the logistic regression model owing to the small sample size. Burrus et al8 investigated the clinical outcomes of ACLR with autograft-allograft hybrid soft tissue grafts compared with hamstring autograft. The authors reported a higher rate of meniscal repair failure with hybrid (38.5%) versus autograft (14.2%) ACLR after a mean follow-up period of approximately 4 years. Similarly, Salem et al42 identified a higher risk of meniscal repair failure with hamstring (35%) versus BTB (14.3%) autografts in young female patients aged 15 to 20 years, and more than two-thirds of failures in the hamstring group occurred in patients with allograft augmentation of an inadequately sized autograft. However, neither of these studies used a multivariate analysis to control for medial versus lateral meniscal repair or activity level. Both of these factors, as well as ACL graft type, were shown to be independent predictors of meniscal repair failure in our study.

Although the exact mechanism behind these findings is unknown, we propose 2 possible explanations. The first is related to the biomechanical influence of graft choice in ACLR. The ACL is the primary restraint to anterior and rotational knee translation, and the medial and lateral menisci serve as secondary knee stabilizers in these respective directions.6,17,26,34,35,46,47,52 Intuitively, a graft that provides less stability than the native ACL provides may subject the menisci to increased strain and, thus, create a suboptimal environment for a repair to heal adequately. This notion is supported by a biomechanical investigation that found ACL insufficiency to increase the amount of strain placed on the medial meniscus in knees resisting an anterior tibial load.2 In another cadaveric study, longitudinal meniscal tears in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus demonstrated significantly wider gaps after ACL transection.31 In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the outcomes of ACLR with concomitant meniscal surgery, it was found that ACLR combined with meniscal repair results in decreased anterior knee laxity compared with ACLR combined with meniscal resection.43 ACLR with BTB autograft has been shown to provide increased knee stability compared with soft tissue autografts and allografts.12,19,25,44,56 Perhaps, this increased stability enhances healing conditions for meniscal repairs.

Considering the potential effect of ACL laxity on meniscal repair success, graft rupture is worthy of individual mention. Previous literature has implicated graft type as a predictor of failed ACLR, and ACL insufficiency has been shown to expose medial meniscal tears to higher loads.2,3,31 It is known that the risk of ACL reinjury is increased with allografts compared with autografts23,30 and with soft tissue autografts compared with BTB autografts, particularly in young athletes.24,30,42 In the current study, subsequent meniscal surgeries that were performed concomitantly with revision ACLR were included in our analysis. Although including this subset of patients may have compromised the internal validity of our study, it strengthened its external validity by minimizing selection bias. In doing so, our findings are more generalizable and, thus, translatable to the care of our patients.18,50 Meniscal preservation is key to the long-term health of the knee. In the setting of a meniscal repair, the surgeon must be aware that ACL allografts may increase the risk of meniscal repair failure when the graft is intact and these allografts tear at a higher rate, which also puts the meniscal repair at risk.

Our second potential explanation pertains to the biochemical effect of intra-articular allograft transplants. It has been shown that serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels are increased in patients with allograft versus autograft ACLR.27 Although a thorough discussion of specific biomarkers and their effect on the healing capacity of meniscal tissue is beyond the scope of the current study, the interplay between pro- and anti-inflammatory conditions and the activity of meniscal fibrochondrocytes has been well described.9,10,13,16,29,49 In a recent study, Cook et al10 described how proinflammatory mediators directly influence degradative processes of the meniscus. Moreover, it has been shown that some inflammatory cytokines have a more potent degradative effect on meniscal tissue compared with cartilage.33,36,37 The alloimmunogenic response evoked by donor grafts may hinder the healing process in repaired menisci and contribute to an increased risk of failure. Conversely, it can be argued that an increased inflammatory response may result in improved wound healing, but in vivo studies on this topic may be necessary.

Our multivariate analysis revealed no significant relationship between meniscal repair failure and patient age at the time of index surgery. Among patients with a failed meniscal repair, the distribution of age was similar across the BTB autograft (18 years; IQR, 15-22 years), soft tissue autograft (18.5 years; IQR, 15-27 years), and allograft (17 years; IQR, 16.5-33.5 years) groups. However, age appeared to be more widely distributed among all patients regardless of the outcome, with a stepwise increase in median age from the BTB autograft (18 years; IQR, 16-26 years) to the soft tissue autograft (22 years; IQR, 16-28 years) and allograft (28 years; IQR, 18-37 years) groups (Table 3). Lyman et al28 identified younger age as an independent risk factor for meniscectomy after meniscal repair using multivariate regression analysis. In the current study, patients in the BTB autograft group appeared to be the youngest and still experienced the lowest rate of meniscal repair failure compared with the allograft (oldest) group.

We identified a significantly increased risk of failure following medial versus lateral meniscal repair. The odds of failure within 6 years of surgery for patients with only a lateral meniscal repair were 68% less than were those with only a medial meniscal repair. A previous study utilizing the first 3 years of the same database (enrollment between 2002 and 2004) with identical follow-up length and definition of repair failure investigated the operative success of meniscal repair when performed concurrently with ACLR.54 The authors found similar failure rates after medial (13.6%) and lateral (13.9%) meniscal repair. However, the sample size in the present study is almost 3 times larger and thus allowed us to identify a significantly increased failure rate with medial (17.6%) versus lateral (8.0%) repairs. Lyman et al28 evaluated risk factors for subsequent meniscectomy after meniscal repair in 9529 patients and, similar to the present study, found an increased risk with medial versus lateral repair. In our series, there was insufficient evidence to show a difference in risk of meniscal repair failure in patients with simultaneous medial and lateral repair compared with those with only a medial meniscal repair. Similarly, in a consecutive series of 918 patients, Ronnblad et al40 reported that medial meniscal repairs had a higher failure rate than lateral meniscal repairs had. This may suggest that the medial repair is what increases risk, regardless of whether the lateral meniscus was also repaired. However, only 39 patients had both medial and lateral repairs, so it is possible there was inadequate power to detect the difference if it does exist.

The current study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first effort to analyze the effect of ACL graft type on the outcomes of meniscal repair when performed at the time of ACLR. The large-scale, multicenter nature of our study allows for improved external validity by including patients in 6 different states who underwent surgery at 7 distinct institutions. Before this investigation, the largest cohort of patients with long-term follow-up who underwent combined meniscal repair and ACLR was 235 patients.54 By utilizing the same database with nearly a 3-fold increase in sample size, the present study identified a significantly increased risk of failure with medial versus lateral meniscal repairs. This difference was not identified in the previous study, possibly because of type 2 error.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. Although the generalizability of our results is improved by the inclusion of multiple surgeons, this also has the potential of introducing confounding variables based on individual surgeon preferences. These include repair technique, type of suture or implant, decision to repair versus excise, choice of ACL graft, and graft placement technique. As the surgeon who chooses the graft type also makes the decision to repair the meniscus and which technique to employ, there may be a relationship between the surgeon and the outcome that is unrelated to graft choice. Another limitation is the lack of proof that ACL grafts were functionally intact without arthrometric or pivot-shift data. Patients who underwent revision ACLR at the time of subsequent meniscal surgery were included in our analysis. This may have affected the internal validity of our study; however, it strengthened its external validity by minimizing selection bias. In addition, the number of patients who underwent hybrid allograft-autograft ACLRs was small (n = 2), so these patients were excluded from our analysis. Last, based on our definition of surgical failure, patients with inadequate healing of a meniscal repair who did not undergo further surgical treatment were not included in our results.

Conclusion

ACL graft type was found to influence the outcome of meniscal repairs performed at the time of ACLR in that meniscal repairs failed at the lowest rate when concomitant ACLR was performed using a BTB autograft. Meniscal repairs performed at the time of ACLR with allograft were 2.3 times more likely to fail compared with those with BTB autograft. There were no differences for autograft BTB and hamstring grafts. Thus, regardless of patient age or activity level, the use of allograft is discouraged when a repairable meniscal tear is encountered at the time of ACLR. The odds of failure were significantly higher following medial versus lateral meniscal repair. Patients with low or high baseline activity levels were also at an increased risk. Of the tested variables, meniscal repair location (medial vs lateral) and baseline activity level were the 2 main drivers of meniscal repair outcomes, and ACL graft type was ranked third.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the research coordinators, analysts, and support staff from the MOON sites, whose efforts related to regulatory requirements, data collection, patient follow-up, data quality control, analyses, and manuscript preparation have made this consortium successful. They also thank all the patients who generously enrolled and participated in this study. Finally, thanks go to Brittany Stojsavljevic, editorial assistant, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, for editorial management.

AUTHORS: Annunziato Amendola, MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA); Jack T. Andrish, MD (Department of Orthopaedics, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Garfield Heights, Ohio, USA); Robert H. Brophy, MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, Chesterfield, Missouri, USA); Morgan H. Jones, MD, MPH (Department of Orthopaedics, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Garfield Heights, Ohio, USA); Christopher C. Kaeding, MD (Department of Orthopaedics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA); Robert G. Marx, MD, MSc (Department of Orthopaedics, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, New York, USA); Matthew J. Matava, MD (Department of Orthopaedics, Washington University School of Medicine, Chesterfield, Missouri, USA); Richard D. Parker, MD (Department of Orthopaedics, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Garfield Heights, Ohio, USA); Michelle L. Wolcott, MD (CU Sports Medicine, Boulder, Colorado, USA); Brian R. Wolf, MD, MS (Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA); Rick W. Wright, MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri, USA).

Final revision submitted March 1, 2021; accepted March 19, 2021.

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award No. R01AR053684 (to K.P.S.) and under award No. K23AR066133, which supported a portion of M.H.J.’s professional effort. Contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Cleveland Clinic (IRB 3867).

References

- 1.Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005-2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2333–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen CR, Wong EK, Livesay GA, Sakane M, Fu FH, Woo SL. Importance of the medial meniscus in the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(1):109–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atarod M, Frank CB, Shrive NG. Increased meniscal loading after anterior cruciate ligament transection in vivo: a longitudinal study in sheep. Knee. 2015;22(1):11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber FA. What is the terrible triad? Arthroscopy. 1992;8(1):19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barenius B, Forssblad M, Engström B, Eriksson K. Functional recovery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a study of health-related quality of life based on the Swedish National Knee Ligament Register. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(4):914–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bargar WL, Moreland JR, Markolf KL, Shoemaker SC, Amstutz HC, Grant TT. In vivo stability testing of post-meniscectomy knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;150:247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borchers JR, Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Huston LJ, Spindler KP, Wright RW. Intra-articular findings in primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a comparison of the MOON and MARS study groups. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1889–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burrus MT, Werner BC, Crow AJ, et al. Increased failure rates after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with soft-tissue autograft-allograft hybrid grafts. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(12):2342–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chastain KS, Stoker AM, Bozynski CC, Leary EV, Cook JL. Metabolic responses of meniscal tissue to focal collagenase degeneration. Connect Tissue Res. 2020;61(3-4):349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook AE, Cook JL, Stoker AM. Metabolic responses of meniscus to IL-1β. J Knee Surg. 2018;31(9):834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox CL, Huston LJ, Dunn WR, et al. Are articular cartilage lesions and meniscus tears predictive of IKDC, KOOS, and Marx activity level outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A 6-year multicenter cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1058–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cristiani R, Sarakatsianos V, Engström B, Samuelsson K, Forssblad M, Stålman A. Increased knee laxity with hamstring tendon autograft compared to patellar tendon autograft: a cohort study of 5462 patients with primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(2):381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Albornoz PM, Forriol F. The meniscal healing process. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2(1):10–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn WR, Wolf BR, Amendola A, et al. Multirater agreement of arthroscopic meniscal lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(8):1937–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairbank TJ. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30B(4):664–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferretti M, Srinivasan A, Deschner J, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of continuous passive motion on meniscal fibrocartilage. J Orthop Res. 2005;23(5):1165–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank JM, Moatshe G, Brady AW, et al. Lateral meniscus posterior root and meniscofemoral ligaments as stabilizing structures in the ACL-deficient knee: a biomechanical study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(6):2325967117695756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gobbi A, Domzalski M, Pascual J. Comparison of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in male and female athletes using the patellar tendon and hamstring autografts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12(6):534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hettrich CM, Dunn WR, Reinke EK, Spindler KP. The rate of subsequent surgery and predictors after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: two- and 6-year follow-up results from a multicenter cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1534–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones MH, Spindler KP, Andrish JT, et al. Differences in the lateral compartment joint space width after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: data from the MOON onsite cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(4):876–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones MH, Spindler KP, Fleming BC, et al. Meniscus treatment and age associated with narrower radiographic joint space width 2-3 years after ACL reconstruction: data from the MOON onsite cohort. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(4):581–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Reinke EK, Huston LJ, Spindler KP. Risk factors and predictors of subsequent ACL injury in either knee after ACL reconstruction: prospective analysis of 2488 primary ACL reconstructions from the MOON cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1583–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaeding CC, Spindler KP, Huston LJ, Zajichek A. ACL reconstruction in high school and college-aged athletes: does autograft choice affect recurrent ACL revision rates? Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(7)(suppl 5):2325967119S00282. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SJ, Choi CH, Kim SH, et al. Bone--patellar tendon--bone autograft could be recommended as a superior graft to hamstring autograft for ACL reconstruction in patients with generalized joint laxity: 2- and 5-year follow-up study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(9):2568–2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy IM, Torzilli PA, Warren RF. The effect of medial meniscectomy on anterior-posterior motion of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(6):883–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Wang J, Li Y, Shao D, You X, Shen Y. A prospective randomized study of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autograft, gamma-irradiated allograft, and hybrid graft. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(7):1296–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyman S, Hidaka C, Valdez AS, et al. Risk factors for meniscectomy after meniscal repair. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(12):2772–2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madhavan S, Anghelina M, Sjostrom D, Dossumbekova A, Guttridge DC, Agarwal S. Biomechanical signals suppress TAK1 activation to inhibit NF-kappaB transcriptional activation in fibrochondrocytes. J Immunol. 2007;179(9):6246–6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maletis GB, Inacio MC, Desmond JL, Funahashi TT. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: association of graft choice with increased risk of early revision. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(5):623–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin M, Stefan V, Andreas S, Lutz D. Influence of anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency on meniscal loading. Orthop Proc. 2011;93-B(suppl II):160–161. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marx RG, Stump TJ, Jones EC, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Development and evaluation of an activity rating scale for disorders of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNulty AL, Miller MR, O’Connor SK, Guilak F. The effects of adipokines on cartilage and meniscus catabolism. Connect Tissue Res. 2011;52(6):523–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minami T, Muneta T, Sekiya I, et al. Lateral meniscus posterior root tear contributes to anterolateral rotational instability and meniscus extrusion in anterior cruciate ligament-injured patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(4):1174–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Musahl V, Citak M, O’Loughlin PF, Choi D, Bedi A, Pearle AD. The effect of medial versus lateral meniscectomy on the stability of the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(8):1591–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimuta JF, Levenston ME. Adipokines induce catabolism of newly synthesized matrix in cartilage and meniscus tissues. Connect Tissue Res. 2017;58(3-4):246–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishimuta JF, Levenston ME. Meniscus is more susceptible than cartilage to catabolic and anti-anabolic effects of adipokines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(9):1551–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paletta GA, Jr, Levine DS, O’Brien SJ, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Patterns of meniscal injury associated with acute anterior cruciate ligament injury in skiers. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20(5):542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberson TA, Abildgaard JT, Wyland DJ, et al. “Proprietary processed” allografts: clinical outcomes and biomechanical properties in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(13):3158–3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ronnblad E, Barenius B, Engström B, Eriksson K. Predictive factors for failure of meniscal repair: a retrospective dual-center analysis of 918 consecutive cases. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(3):2325967120905529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roos H, Lauren M, Adalberth T, Roos EM, Jonsson K, Lohmander LS. Knee osteoarthritis after meniscectomy: prevalence of radiographic changes after twenty-one years, compared with matched controls. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(4):687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salem HS, Varzhapetyan V, Patel N, Dodson CC, Tjoumakaris FP, Freedman KB. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young female athletes: patellar versus hamstring tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(9):2086–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarraj M, Coughlin RP, Solow M, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with concomitant meniscal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(11):3441–3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shakked R, Weinberg M, Capo J, Jazrawi L, Strauss E. Autograft choice in young female patients: patella tendon versus hamstring. J Knee Surg. 2017;30(3):258–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shelbourne KD, Nitz PA. The O’Donoghue triad revisited: combined knee injuries involving anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligament tears. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):474–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shybut TB, Vega CE, Haddad J, et al. Effect of lateral meniscal root tear on the stability of the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spang JT, Dang ABC, Mazzocca A, et al. The effect of medial meniscectomy and meniscal allograft transplantation on knee and anterior cruciate ligament biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(2):192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spindler KP, Huston LJ, Chagin KM, et al. Ten-year outcomes and risk factors after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a MOON longitudinal prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(4):815–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spindler KP, Mayes CE, Miller RR, Imro AK, Davidson JM. Regional mitogenic response of the meniscus to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-AB). J Orthop Res. 1995;13(2):201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steckler A, McLeroy KR. The importance of external validity. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):9–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walker PS, Arno S, Bell C, Salvadore G, Borukhov I, Oh C. Function of the medial meniscus in force transmission and stability. J Biomech. 2015;48(8):1383–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warren RF, Levy IM. Meniscal lesions associated with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;172:32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Westermann RW, Wright RW, Spindler KP, Huston LJ, Wolf BR. Meniscal repair with concurrent anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: operative success and patient outcomes at 6-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(9):2184–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wright RW, Haas AK, Anderson J, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation: MOON guidelines. Sports Health. 2015;7(3):239–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xie X, Liu X, Chen Z, Yu Y, Peng S, Li Q. A meta-analysis of bone--patellar tendon--bone autograft versus four-strand hamstring tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2015;22(2):100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]