Abstract

Background and study aims Prognostic and risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) might have changed overtime because of the increased use of direct oral anticoagulants and improved gastroenterological care. This study was undertaken to assess the outcomes of UGIB in light of these new determinants by establishing a new national, multicenter cohort 10 years after the first.

Methods Consecutive outpatients and inpatients with UGIB symptoms consulting at 46 French general hospitals were prospectively included between November 2017 and October 2018. They were followed for at least for 6 weeks to assess 6-week rebleeding and mortality rates and factors associated with each event.

Results Among the 2498 enrolled patients (mean age 68.5 [16.3] years, 67.1 % men), 74.5 % were outpatients and 21 % had cirrhosis. Median Charlson score was 2 (IQR 1–4) and Rockall score was 5 (IQR 3–6). Within 24 hours, 83.4 % of the patients underwent endoscopy. The main causes of bleeding were peptic ulcers (44.9 %) and portal hypertension (18.9 %). The early in-hospital rebleeding rate was 10.5 %. The 6-week mortality rate was 12.5 %. Predictors significantly associated with 6-week mortality were initial transfusion (OR 1.54; 95 %CI 1.04–2.28), Charlson score > 4 (OR 1.80; 95 %CI 1.31–2.48), Rockall score > 5 (OR 1.98; 95 %CI 1.39–2.80), being an inpatient (OR 2.45; 95 %CI 1.76–3.41) and rebleeding (OR 2.6; 95 %CI 1.85–3.64). Anticoagulant therapy was not associated with dreaded outcomes.

Conclusions The 6-week mortality rate remained high after UGIB, especially for inpatients. Predictors of mortality underlined the weight of comorbidities on outcomes.

Introduction

During the past decade, European and American endoscopy and hepatology societies have updated their guidelines concerning the management of variceal or non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) to improve gastroenterological care and ultimately patient outcomes 1 2 3 4 . Nevertheless, UGIB remains a frequent health problem with a mortality rate that remains high 5 6 .

The first prospective, national, multicenter study was conducted in 53 French general hospitals in 2005 and included 3203 outpatients 7 with a mortality rate of 8.3 %. Independent predictors of mortality were Rockall score, comorbidities, and systolic blood pressure < 100 mm Hg at first consultation. A substudy on bleeding peptic ulcers showed a slight decrease in UGIB-linked mortality, attributed to improved prevention, better adherence to guidelines, and better comorbidity support 8 .

Potential risk and prognostic factors for UGIB may have evolved in developed countries, particularly with the increased use of direct oral anticoagulants to treat thromboembolic diseases, improved gastroenterological management with the use of new effective endoscopic hemostatic devices, and in some countries, the development of expert regional endoscopic care. UGIB-associated prognostic factors in this context have been investigated in only a few studies, and most of the recent epidemiological data refer to bleeding ulcers, rather than portal hypertensive bleeding.

Therefore, we undertook the Saignements digestifs ANGH Registre Incidence Actualisée (SANGHRIA) trial to assess UGIB outcomes, in light of these new determinants by establishing a new national, multicenter cohort 10 years after the first and to identify risk factors for rebleeding and mortality.

Patients and methods

From November 2017 to October 2018, patients fulfilling the following inclusion criteria were prospectively included in 46 general hospitals in France. UGIB was defined as hematemesis and/or melena and/or acute anemia. For patients with acute anemia, the endoscopist had to find blood in the upper digestive tract (or a lesion) to confirm the patient’s inclusion in the study. The patients included in the study were classified in two groups: patients admitted to Emergency Departments with UGIB symptoms (outpatients) and those already hospitalized for other reasons than UGIB (inpatients).

Patients < 18 years old were excluded, as were those under legal guardianship. This trial was first registered with French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (ANSM ID RCB no. 2017-A01920–53) and received Ethics Committee approved (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud Méditerranée II) in May 2017. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all applicable local regulations and French law. Written information was provided to all patients and they were able to accept or decline their participation by verbal non-opposition. The data were collected in an electronic case-report form and were monitored by a study-designated Clinical Research Associate.

Epidemiological, clinical and biological data

These data were collected prospectively at the time of inclusion: age, sex, body mass index, Charlson comorbidity score 9 , smoking status, alcohol consumption (excessive > 30 g/day), history of peptic ulcer and Helicobacter pylori status, heart rate and blood pressure at admission and the need for resuscitation. For patients with cirrhosis, its etiology, the Child-Pugh classification were noted, and the Model for End-stage Liver Disease score was calculated. Each inpatient’s initial hospitalization unit was documented. Relevant treatments were recorded, such as, type of anticoagulant treatment (vitamin-K antagonist or direct oral anticoagulant), antiplatelet agents, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and beta-blockers.

Shock was defined as systolic blood pressure < 100 mm Hg and pulse rate > 100/minute. Treatment modalities and details of blood transfusions were left to the discretion of the treating physician.

Endoscopic data

Endoscopic information was collected but also time to the procedure, presence of an endoscopic assistant, anesthesia use, calculations of the Rockall and Glasgow-Blatchford scores 10 11 and detailed type of endoscopic treatment.

Outcomes

The following information was collected during the 6-week follow-up period: 1) surgical or radiological intervention; 2) length of hospitalization; 3) need for transfusion; 4) rebleeding; 5) morbidity; and 6) all causes of death. Patients were followed for at least 6 weeks to know about rebleeding, readmission or death. Early rebleeding was defined as recurrent bleeding before discharge, and late rebleeding was defined as recurrent bleeding occurring between discharge and 6-week follow-up. For statistical analyses, early and late rebleeding rates were combined.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean and standard deviation [SD], or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. Univariate analyses used a Student’s t -test to compare quantitative variables and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables. Step-wise logistic-regression analysis identified factors predictive of rebleeding and mortality. Significant variables with P ≤ 0.20 in univariate analyses were included in the stepwise logistic-regression multivariate model. The odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval (CI) were calculated for each independent factor. A two-tailed P < 0.05 defined statistical significance. Statistical analyses were computed with SPSS software (version 18).

Results

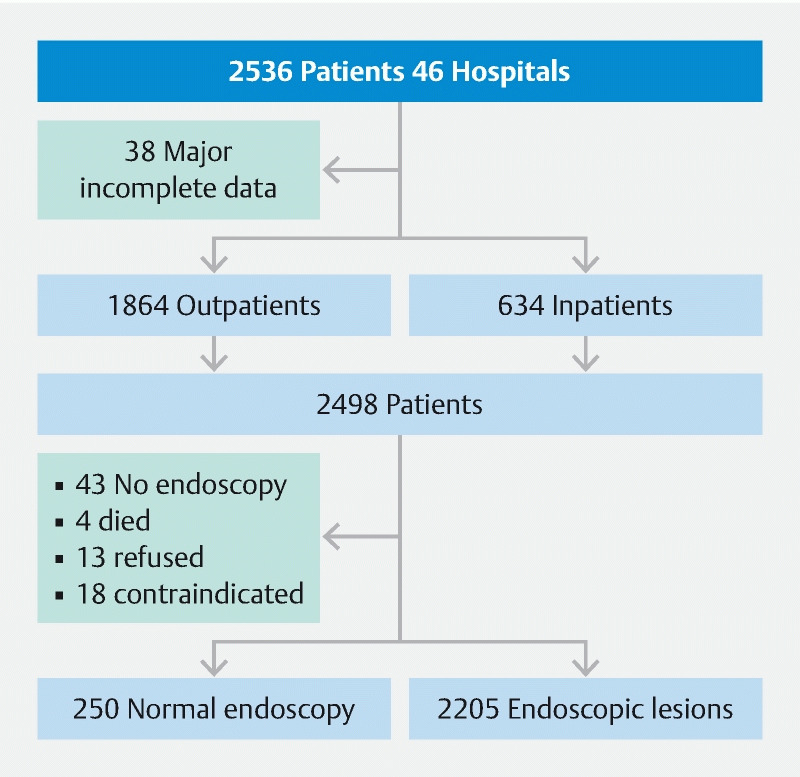

During the study period, 2536 patients were initially enrolled and, after excluding 38 for missing essential data, 2498 remained for analysis (1677 men and 821 women; mean age 68.5 [16.3] years) ( Fig. 1 ). Among them, 1864 (74.5 %) were outpatients and 634 (25.5 %) were inpatients.

Fig. 1 .

Flowchart of the population.

Study population

Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1 . Among the 524 patients (20.9 %) with known cirrhosis, 22.5 % were Child-Pugh classification stage C. Origin of cirrhosis was alcoholism for 80.0 % of them, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis for 9.0 % and viral hepatitis infection for 4.2 %.

Table 1. Study population: demographic and clinical characteristics, and laboratory findings.

| Characteristic | Data available | Value 1 |

| Clinical | ||

|

2498 | 1677 (67.1)/821 (32.9) |

|

2498 | 68.5 [16.3] |

|

954 (38.2) | |

|

2327/2498 | 25.9 [5.7] |

|

2497/2498 | 524 (20.9) |

|

464/524 | 8.38 [2.3] |

|

433/524 | 15.9 [6.9] |

|

2497/2498 | 2.71 [2.5] |

|

2417/2498 | 10.3 [4.4] |

|

2469/2498 | 630 (25.5) |

| Laboratory | ||

|

2488/2498 | 9 [2.9] |

|

2481/2498 | 9.47 [2.3] |

|

2469/2498 | 8.2 [2.97] |

|

519/524 | 54.8 [18.5] |

|

2376/2498 | 70 [22] |

|

298/524 | 61.9 [24.1] |

|

2479/2498 | 221258 [119156] |

|

518/524 | 44.8 [60.5] |

|

960/2498 | 111.4 [78.1] |

|

2455/2498 | 14.1 [11.2] |

|

464/524 | 28.5 [6.5] |

Categorical variables are expressed as number (percentage); continuous variables as mean [standard deviation].

Melena, associated or not with other inclusion criteria, was present in 73.9 % of the patients. At admission, mean systolic blood pressure was 120 [26.4] mmHg and mean pulse rate was 92 [20.5] beats/minute.

Medications with a potential bleeding risk being taken at admission are summarized in Table 2 . At first consultation, 777 patients (31.1 %) had ongoing PPIs. Beta-blockers were prescribed for 195 cirrhotic patients (37.2 %), mainly propranolol for 125 (64.1 %).

Table 2. Drugs being taken at admission with a potential risk of causing upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

| Treatment | n/2498 (%) |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone | 172 (6.9) |

| Aspirin alone | 527 (21.1) |

| Antiplatelet alone | 189 (7.6) |

| Oral anticoagulant alone or in combination | 489 (19.6) |

|

267 (54.6) |

|

208 (42.5) |

|

14 (2.9) |

| Aspirin + antiplatelet | 135 (5.4) |

| Aspirin + anticoagulant | 115 (4.6) |

| Antiplatelet + anticoagulant | 36 (1.4) |

| Aspirin + antiplatelet + anticoagulant | 20 (0.8) |

| None of the above | 928 (37.1) |

Initial management

All patients had a saline or other infusion for endoscopy but the hemodynamic status of only 700 of 2498 (28.0 %) required intensive resuscitation with isotonic, intravenous (IV) fluid support before upper endoscopy; 257 of 2498 (10.3 %) were in shock. Initial red blood-cell transfusion(s) were given to 1214 patients (48.6 %). The mean initial hemoglobin level of the 1214 patients who received blood transfusion(s) was 7 [1.6] g/dL; among them, 312 (25.7 %) had hemoglobin levels ≥ 8 g/dL and 54 (4.4 %) had levels ≥ 10 g/dL. The mean number of units was 2.36 (1.09) and the median hemoglobin level at endoscopy was 9 g/dL (IQR 7.9–10.6).

Among patients with portal hypertension and rebleeding, the initial transfusion rate did not differ according to when the bleeding event occurred or not (51.1 % vs 48.9 % respectively; P = 0.28), the total mean number of red cell units transfused into rebleeders was higher than for non-bleeders (4.1 [2.8] vs 2.9 [1.5] respectively; P < 0.0001). Deceased patients with portal hypertension had a higher initial transfusion rate than survivors (57.3 % vs 42.7 %, respectively; P = 0.029) and a higher total mean number of units transfused (3.6 [2.5] vs 3.0 [1.7], respectively; P = 0.039).

Coagulopathy reversion was needed for 297 patients (11.9 %), most frequently with vitamin K (108/297, 36.5 %) or fresh-frozen plasma (101/297, 34.1 %). IV PPIs were initiated for 2114 patients (84.8 %) prior to endoscopy, most often with an 80-mg infusion, followed by 8 mg per hour continuous infusion for 1261 (59.8 %). Octreotide or terlipressin was prescribed for 639 patients (25.6 %) (administered in the Emergency Department just before endoscopy).

Endoscopic procedure and results

Among the 2455 endoscopies (98.3 %) performed, 2067 (83.4 %) were done within 24 hours after arrival in the Emergency Department for outpatients or after learning of the bleeding for inpatients, with prior IV erythromycin administration for 545 (21.9 %). %). Endoscopy was done within 24 hours for 92.9 % of the patients with shock and 82.2 % of those without ( P < 0.0001). Among all of them, endoscopy was performed within 6 hours in 52.5 % of patients with shock and 30.9 % of those without shock ( P < 0.0001). A senior physician performed 83.1 % of the procedures, with an endoscopic assistant for 2248 patients (91.7 %) (most often a specialized nurse) and the percentages of endoscopy assistants available were similar for endoscopies done on weekdays or during weekends. General anesthesia was given to 30.9 % of the patients, 60.1 % of whom were intubated. The endoscopist had access to a water pump during 84.9 % of the examinations, and endoscopy quality was considered satisfactory for 84.6 %, moderately satisfactory for 9.9 % and unsatisfactory for 3.3 % (with 2.3 % missing data).

Forty-three patients did not undergo endoscopy: 18 had a contraindication, 13 refused, four patients died before endoscopy, one was transferred, and data were missing for seven. Endoscopy was considered normal for 250.

The lesions diagnosed and main causes of bleeding, detailed in Table 3 , were: 1) peptic ulcers and gastroduodenal ulcers or erosions (44.9 %); 2) related to portal hypertension (18.9 %); and 3) esophagitis (11.4 %). The median Rockall score was 5 (IQR 3–6). Among patients with portal hypertension-related bleeding, 160 (23.4 %) were newly diagnosed with cirrhosis during the endoscopy.

Table 3. Type of lesions and main causes of bleeding.

| Type of lesion 1 | n/N | Main cause of bleeding (/2205) 2 |

| Ulcers or erosions | /1145 | 990 (44.9) |

| Esophageal | 121 (10.6) | 99 |

| Gastric | 437 (38.2) | 372 |

| Duodenal | 587 (51.3) | 519 |

| Forrest classification | /417 | |

| Ia | 8 (1.9) | |

| Ib | 47 (11.3) | |

| IIa | 28 (6.7) | |

| IIb | 56 (13.4) | |

| IIc | 62 (14.9) | |

| III | 216 (51.8) | |

| Portal hypertension | /684 | 416 (18.9) |

| Esophageal varices | 419 (61.3) | 313 |

| Gastric varices | 47 (6.9) | 36 |

| Gastropathy | 215 (31.4) | 64 |

| Duodenal varices | 3 (0.4) | 3 |

| Esophageal varix classification | /411 | |

| Grade 1 | 81 (19.7) | |

| Grade 2 | 198 (48.2) | |

| Grade 3 | 132 (32.1) | |

| Esophagitis | /396 | 251 (11.4) |

| Peptic | 380 (96) | |

| Caustic | 4 (1) | |

| Post-radiotherapy | 4 (1) | |

| Unknown | 8 (2) | |

| Cancer | /121 | 115 (5.2) |

| Esophageal | 31 (25.6) | 29 |

| Gastric | 65 (53.7) | 62 |

| Duodenal | 25 (20.7) | 24 |

| Vascular | /121 | 94 (4.3) |

| Esophageal | 3 (2.5) | 1 |

| Gastric | 71 (58.7) | 56 |

| Duodenal | 47 (38.8) | 37 |

| Mallory-Weiss syndrome | /90 | 86 (3.9) |

| Delayed bleeding/sloughing scab 3 | /23 | 22 (1) |

| Dieulafoy’s lesion | /21 | 21 (1) |

| Others | /336 | 196 (8.9) |

| Esophageal foreign body | 1 (0.3) | 1 |

| Esophagus | 34 (10.1) | 16 |

| Gastric | 196 (58.3) | 127 |

| Duodenal | 105 (31.3) | 52 |

| Missing data | 14 (0.5) | |

| Total | 2205 (100) | |

| Normal endoscopy | 250/2455 | – |

Values are expressed as number (percentages) of available data.

Patients could have multiple lesions.

According to the treating physician’s opinion.

Sloughing scab, defined as dead tissue detaching from a lesion, corresponds to an ulceration bleeding after band ligation or polypectomy.

Outcomes

A median of 3 red blood-cell units (IQR 2–4) were transfused during hospitalization. UGIB required a radiological intervention: embolization for 23 patients (0.9 %) and a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for 20 (0.8 %). Sixty-seven patients (2.7 %) required surgery.

Post-endoscopy hospitalization lasted a median of 7 days (IQR 4–12). Notably, 1042 patients needed an extension of hospitalization (defined as a length of stay longer than that of the duration of the initial critical care treatment period) that was linked to UGIB for 297 patients or unrelated to UGIB for 745. Among the reasons associated with UGIB, most were because of liver failure (67/297, 22.6 %), cancer diagnosis (47/297, 15.8 %) and multiorgan failure (29/297, 9.8 %). The most frequent unrelated UGIB reasons for prolonged hospitalization were comorbidities (549/745, 73.8 %), waiting for convalescent care (106/745, 14.2 %) and waiting for transfer to another hospital (89/745, 12.0 %). The prolonged hospitalizations of 61 patients were linked to UGIB and another cause or unknown data.

Rebleeding, rehospitalization and mortality

During hospitalization, 259 patients (10.5 %) experienced rebleeding; the median time to rebleeding was 2 days (IQR 1–5). Late rebleeding occurred in 158 patients (6.6 %), at a median of 17 days (IQR 7–30). Predictors significantly and independently associated with rebleeding, detailed in Table 4 , were being an inpatient, Glasgow-Blatchford score > 11 or active bleeding, while oral anticoagulant treatment was found to be protective against recurrent bleeding.

Table 4. Multivariate analyses of factors predictive of rebleeding or mortality.

| Factor | P value | Odds ratio | 95 %CI |

| Rebleeding | |||

| Oral anticoagulant | 0.028 | 0.67 | 0.47–0.96 |

| Being an inpatient | 0.028 | 1.36 | 1.03–1.79 |

| Glasgow-Blatchford score > 11 | 0.011 | 1.45 | 1.09–1.95 |

| Active bleeding | 0.0001 | 1.95 | 1.48–2.56 |

| Mortality | |||

| Red blood cell transfusion during resuscitation | 0.031 | 1.54 | 1.04–2.28 |

| Charlson score > 4 | 0.0001 | 1.80 | 1.31–2.48 |

| Rockall score > 5 | 0.0001 | 1.98 | 1.39–2.80 |

| Being an inpatient | 0.0001 | 2.45 | 1.76–3.41 |

| Rebleeding | 0.0001 | 2.6 | 1.85–3.64 |

Mortality during hospitalization was 8.6 % (214 patients) and was significantly lower for outpatients than inpatients (5.8 % vs 16.8 %, respectively ( P < 0.0001); OR 3.26; 95 % CI 2.45–4.33). Eighty-six patients died after discharge, for a 6-week mortality rate of 12.5 % (9.1 % of outpatients vs 22.2 % of inpatients ( P < 0.0001); OR 0.35; 95 % CI 0.27–0.45). The main causes of death during the initial hospitalization were multiorgan failure for 64 patients (29.6 %), directly related to the UGIB for 40 (18.5 %), cancer for 34 (15.7 %), liver dysfunction for 24 (11.1 %), heart or lung failure for 17 (7.9 %) and infection for 16 (7.4 %). Factors significantly and independently associated with the 6-week mortality, detailed in Table 4 , were initial transfusion, Charlson score > 4, Rockall score > 5, being an inpatient or rebleeding.

Descriptive data from the 2005 study exclusively on outpatients are reported in Table 5 , along with those from outpatients included in the SANGHRIA trial.

Table 5. Descriptive data from our two studies conducted 13 years apart.

| Parameter | 2005 (outpatients 1 ) | 2018 (only outpatients) |

| Clinical data | ||

|

63.3 (18.2) | 67.2 (16.8) |

|

31.9 % | 22.5 % |

| Endoscopic features | ||

|

36.9 % | 44.4 % |

|

24.5 % | 21.9 % |

|

9.2 (13.5) | 8.6 (9.1) |

|

9.9 % | 9.2 % |

|

3 % | 3.8 % |

|

8.3 % | 5.8 % |

Nahon et al. [7].

Discussion

Among the 2498 outpatients and inpatients with UGIB included in the SANGHRIA trial, 83.4 % underwent endoscopy within 24 hours that revealed an ulcer in 44.9 % and portal hypertension in 18.9 %. Early rebleeding occurred in 10.5 % of them. The 6-week follow-up mortality was 12.5 %. Mortality differed significantly between outpatients (9.1 %) and inpatients (22.2 %). The main predictors significantly associated with rebleeding and mortality were initial active bleeding and rebleeding.

From an epidemiological point of view, the SANGHRIA-trial results showed that the main causes of UGIB were peptic ulcers or gastroduodenal ulcers or erosions (44.9 %) and portal hypertension-related lesions (18.9 %). Those results indicated that portal hypertension lesions are quite frequent in France. Notably, in the United Kingdom, peptic ulcers accounted for 36 % of UGIB and bleeding varices for 11 % 12 , whereas in Turkey, gastric or duodenal ulcers were estimated at 32 % and esophageal varices at 4.9 % 13 . According to the most recent study in Hong Kong 6 , peptic ulcers were diagnosed in 61.4 % of patients and esophageal or gastric varices in 8.5 %. It is worth emphasizing that cancer was the fourth cause of UGIB herein (only 5.2 % of cases) but was the cause of death for 15.7 %. A Brazilian study 14 also reported this poor prognosis and concluded that UGIB in this patient population must be seen as a life-threatening event.

One of our objectives was to determine whether UGIB management had improved over the past decade. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy issued strong recommendations concerning the time to endoscopy and the use of erythromycin 1 ; in our study, 83.4 % of endoscopies were done within 24 hours vs. 79 % in 2005 7 , and after erythromycin infusion for 21.9 % vs. 14 % of patients, respectively. In comparison, endoscopy within 24 hours of admission (early endoscopy) was only achieved in 58.9 % in a recent UK prospective, multicenter audit 15 . Multivariable analyses in that study showed that independent predictors of delayed endoscopy were lower Glasgow-Blatchford scores, late referral and admissions between 7:00 and 19:00 hours or via the Emergency Department. In that UK audit, early endoscopy was associated with shorter lengths of stay (median difference 1 day; P = 0.004) but not with lower 30-day mortality ( P = 0.34). That latter point warrants further commentary. In our study, too, the time to endoscopy was not associated with mortality in our multivariate analysis. In contrast, a recent large Danish nationwide cohort study, focusing on peptic ulcer bleeding, found that the time to endoscopy was associated with mortality in patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists score of 3 to 5 or hemodynamic instability 16 . For patients in stable condition, Lau et al. reported that urgent endoscopy (< 6 hours) did not lower mortality, compared with early endoscopy (6–24 hours) 6 .

A new major point of the most recent international recommendations is to limit the number of red blood-cell units transfused prior to endoscopy 1 17 . In our previous study, 63 % of patients received transfusion(s) 7 , with a mean number of 3.8 ± 2.6 transfused units, whereas in SANGHRIA trial, only 48.6 % of the patients received initial red blood-cell transfusion(s), for a lower mean of 2.4 ± 1.1 units transfused. Because our SANGHRIA population (in- and outpatients) differed from that of our earlier study (only outpatients) and these studies were not randomized, it is difficult to conclude definitively about the link between over-transfusion and rebleeding or mortality. In our previous study, among patients who received red blood cell transfusion(s), rebleeding (OR 11.3; 95 % CI 7.0–18.3), surgery (OR 5.8; 95 % CI 2.9–11.6), and mortality (2.2; 1.6–2.9) were significantly more frequent than among those not transfused. In the SANGHRIA trial, patients with portal hypertension and rebleeding received significantly more red cell units, and patients who died had received initial transfusion(s) more often and had a higher mean number of units transfused than survivors. Thus, the transfusion rate could not have been a causal factor of death or recurrence in these patients. At most, excess transfusions to achieve > 9 g/dL of hemoglobin can be considered an additional sign of a pejorative outcome, as documented in randomized studies 17 . This restrictive transfusion-strategy recommendation is probably the one most followed: in a 2011 UK study only 43 % of patients were transfused 12 and Lau et al. administered a mean of 2.4 red blood-cell units transfused for urgent and early endoscopy groups 6 .

Not many recommendations address the endoscopy procedure’s environment, for example, general anesthesia or the presence of an endoscopy assistant. Those from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy concerning variceal hemorrhage recommend intubating patients before the procedure and the international consensus guidelines on the management of patients with non-variceal UGIB recommend having support staff trained to assist in endoscopy available on an urgent basis, as do the European Association for the Study of the Liver recommendations 3 4 18 . In the SANGHRIA trial, 30.9 % of endoscopies were done under general anesthesia vs. 12.5 % in 2005. An endoscopy assistant (85 % of whom were specialized nurses) was present during 91.7 % of those interventions and the percentages were similar for endoscopies done on weekdays or during weekends, whereas in 2005, those rates were 85 % on weekdays and 40 % on weekends. To our knowledge, no data on this is item are available from recent, nationwide, cohort studies or audits of daily practice.

These findings about the few items discussed above could lead us to think that endoscopic practices have improved over the past decade.

In the SANGHRIA trial, despite persistently high mortality rates during hospitalization or at 6-week follow-up (8.6 % and 12.5 %, respectively), with inpatients and outpatients differing significantly, comparison of SANGHRIA outpatients and our previous study (hospital mortality of outpatients) tended to show that this rate declined: 5.8 % vs. 8.3 %, respectively. That observation was supported by other analyses during a decade concerning both non-variceal or variceal bleeding in UK inpatients or outpatients 19 . Regarding SANGHRIA-trial overall mortality, it seems to be the same or slightly lower than those from other European studies 12 19 20 .

The two most frequent causes of death in this study were multiorgan failure (29.6 %), followed by those directly UGIB-related (18.5 %). Those observations might be explained by having included inpatients with greater fragility and more comorbidities could be responsible for multiorgan failure, as found by others who focused on peptic ulcer bleeding in an outpatient-and-inpatient cohort 21 . Lowering the mortality rate must therefore also involve optimizing the management of comorbidities.

Our multivariate analyses on potential predictors significantly associated with rebleeding or 6-week mortality confirmed the validity and power of classical scores, e. g., a Glasgow-Blatchford score > 11 for rebleeding and Charlson score > 4 or Rockall score > 5 for mortality. The results of other studies also confirmed the performances of the Glasgow-Blatchford or Rockall scores 22 but their complicated calculations limit their implementation in daily clinical practice. Hence, some new scores have been developed, like the UGIB-risk AIMS65 23 , whose calculation is much easier for at least equivalent performance, especially to predict mortality 24 25 . We did not use the AIMS65 because it was insufficiently known when we designed our trial.

Strengths and limitations

We enrolled a large number of patients in this 1-year, prospective, multicenter trial. Moreover, we had the opportunity to compare inpatients and outpatients, whereas our previous study focused only on outpatients, which represents a real plus. This “real-life” study provided an overview of medical care in French general hospitals (not university centers) that tried to overcome the weaknesses highlighted by of our earlier study 7 . Nahon et al. suggested that it would have been of interest to have information about survival during the 30-day post-endoscopy period and to study early morbidity and mortality rates after hospital discharge 7 . Indeed, studies like ours are sorely lacking in the available literature. Most authors focused their investigations on non-variceal UGIB and/or conducted them in tertiary center(s) and/or without precise endoscopic data and/or sufficiently long follow-up.

The large number of patients included in the SANGHRIA trial provided a database rich in information about daily life, which is usually not available in academic studies. We enrolled inpatients and outpatients, who were followed for at least 6 weeks, thereby providing key advances in our understanding of UGIB.

The design of our study was not optimum for statistical analyses (no randomized analysis) and, because no inpatients were included in our previous study 7 , comparison was limited to outpatients and descriptive remarks.

Conclusions

Although a direct comparison was not possible, the results of this trial highlighted the trend towards improved UGIB management compared to those conducted previously, especially for outpatients. Despite this improvement, mortality at 6-week follow-up remained high, especially for patients who experienced UGIB while they were hospitalized for another reason. This persistently high mortality can be explained by the severity of the underlying disease for which patients were initially admitted. Strong predictors of mortality were in-hospital bleeding and rebleeding, with no major role of anticoagulation therapy. These findings confirmed that previously known predictors were still valid, even after taking into account the recent advances in management of patients with UGIB.

Acknowledgements

The French National Society of Gastroenterology (SNFGE) Fonds d'Aide à la Recherche et à l’Evaluation (FARE) provided a grant for this research. The authors thank Ms. Catherine Bellot and Ms. Marie-Cécile Hervé of the Clinical Research Unit, Centre Hospitalier Saint-Brieuc and Guillaume Bouguen, MD, PhD, of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Rennes

Footnotes

Competing interests Dr. Nahon has received lecture fees from MSD, Takeda and Sandoz, and consulting fees from MSD, Takeda, Janssen, Sandoz, Ferring, and Vifor. Dr. Arotcarena has received funds from Gilead and Abbvie to attend meetings. Dr. Macaigne has received funding from Jansen, Takeda, Abbvie, and Tillots to attend meetings.

Contributor Information

Members of the Association Nationale des Hépato-gastroentérologues des Hôpitaux Généraux (ANGH) SANGHRIA Study Group:

Christophe Agnello, Frédérique Alabert, Morgane Amil, Yves Arondel, Ramuntcho Arotcarena, Jean-Pierre Arpurt, Karim Aziz, Mathieu Baconnier, Sandrine Barge, Georges Barjonet, Julien Baudon, Lucile Bauguion, Marie Bellecoste, Serge Bellon, Alban Benezech, Aliou Berete, Chantal Berger, Jean-Guy Bertolino, Karine Bideau, Gaëlle Billet, Massimo Bocci, Isabelle Borel, Madina Boualit, Dominique Boutroux, Slim Bramli, Pascale Catala, Claire Charpignon, Jonathan Chelly, Marie Colin, Rémi Combes, Laurent Costes, Baya Coulibaly, David Cuen, Gaëlle D'hautefeuille, Hortense Davy, Mercedes De Lustrac, Stéphanie De Montigny-Lenhardt, Jean-Bernard Delobel, Anca-Stela Dobrin, Florent Ehrhard, Weam El Hajjl, Khaldoun Elriz, Anouk Esch, Roger Faroux, Mathilde Fron, Cécile Garceau, Armand Garioud, Edmond Geagea, Denis Grasset, Loïc Guerbau, Jessica Haque, Florence Harnois, Frédéric Heluwaert, Denis Heresbach, Sofia Herrmann, Clémence Horaist, Mehdi Kaassis, Jean Kerneis, Carelle Koudougou, Ludovic Lagin, Margot Laly, You-Heng Lam, Rachida Leblanc-Boubchir, Antonia Legruyer, Delphine Lemee, Christophe Locher, Dominique Louvel, Henri Lubret, Gilles Macaigne, Vincent Mace, Emmanuel Maillard, Magdalena Meszaros, Mohammed Redha Moussaoui, Stéphane Nahon, Amélie Nobecourt, Etienne Pateu, Thierry Paupard, Arnaud Pauwels, Agnès Pelaquier, Olivier Pennec, Mathilde Petiet, Fabien Pinard, Vanessa Polin, Marc Prieto, Gilles Quartier, Vincent Quentin, André-Jean Remy, Marie-Pierre Ripault, Isabelle Rosa, Thierry Salvati, Matthieu Schnee, Leila Senouci, Florence Skinazi, Nathalie Talbodec, Quentin Thiebault, Ivan Touze, Marie Trompette, Laurent Tsakiris, Hélène Vandamme, Charlotte Vanveuren, Juliette Verlynde, Joseph Vickola, René-Louis Vitte, Faustine Wartel, Oana Zaharia, David Zanditenas, and Patrick Zavadil

References

- 1.Gralnek I, Dumonceau J-M, Kuipers E et al. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwang J H, Fisher D A, Ben-Menachem T et al. The role of endoscopy in the management of acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1132–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang J H, Shergill A K, Acosta R D et al. The role of endoscopy in the management of variceal hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Franchis R. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sey M SL, Mohammed S B, Brahmania M et al. Comparative outcomes in patients with ulcer- vs non-ulcer-related acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the United Kingdom: a nationwide cohort of 4474 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:537–545. doi: 10.1111/apt.15092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau J YW, Yu Y, Tang R SY et al. Timing of Endoscopy for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1299–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahon S, Hagège H, Latrive J P et al. Epidemiological and prognostic factors involved in upper gastrointestinal bleeding: results of a French prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:998–1008. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeitoun J-D, Rosa-Hézode I, Chryssostalis A et al. Epidemiology and adherence to guidelines on the management of bleeding peptic ulcer: a prospective multicenter observational study in 1140 patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlson M E, Pompei P, Ales K L et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rockall T A, Logan R F, Devlin H B et al. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316–321. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blatchford O, Murray W R, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet Lond Engl. 2000;356:1318–1321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hearnshaw S A, Logan R FA, Lowe D et al. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327–1335. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaya E, Karaca M A, Aldemir D et al. Predictors of poor outcome in gastrointestinal bleeding in emergency department. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4219. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i16.4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maluf-Filho F, da Martins B C, de Lima M S et al. Etiology, endoscopic management and mortality of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cancer. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:60–67. doi: 10.1177/2050640612474652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siau K, Hodson J, Ingram R et al. Time to endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Results from a prospective multicentre trainee-led audit. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:199–209. doi: 10.1177/2050640618811491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laursen S B, Leontiadis G I, Stanley A J et al. Relationship between timing of endoscopy and mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a nationwide cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:936–944000. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A et al. Transfusion Strategies for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barkun A N, Bardou M, Kuipers E J et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101–113. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crooks C, Card T, West J. Reductions in 28-day mortality following hospital admission for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:62–70. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenstock S J, Møller M H, Larsson H et al. Improving Quality of care in peptic ulcer bleeding: nationwide cohort study of 13,498 consecutive patients in the Danish Cinical Register of Emergency Surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1449–1457. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sung J JY, Tsoi K KF, Ma T KW et al. Causes of mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective cohort study of 10,428 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:84–89. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryant R V, Kuo P, Williamson K et al. Performance of the Glasgow-Blatchford score in predicting clinical outcomes and intervention in hospitalized patients with upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saltzman J R, Tabak Y P, Hyett B H et al. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1215–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson M, Majumdar A, Boyapati R et al. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1151–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martínez-Cara J G, Jiménez-Rosales R, Úbeda-Muñoz M et al. Comparison of AIMS65, Glasgow-Blatchford score, and Rockall score in a European series of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: performance when predicting in-hospital and delayed mortality. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:371–379. doi: 10.1177/2050640615604779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]