Abstract

Objective

To conduct a nationwide assessment of communication by participating states and Washington DC about the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot expansion.

Design

Systematic coding of official communication from state and DC SNAP administrating agencies.

Participants

Forty-six states and DC approved to participate in the pilot as of October 2020 (n = 47). Data were collected from official SNAP administrating agency websites, state press releases, and state emergency coronavirus disease 2019 websites.

Variables Measured

Four domains were collected from communication materials: (1) program information, (2) retailer information, (3) health and nutrition information, and (4) communication accessibility.

Analysis

Qualitative content analysis, descriptive statistics.

Results

Thirty-four (72%) states issued an official press release about the pilot that was easily accessible through online searches (15 available in multiple languages), 21 (45%) included information on their SNAP agency website, and 15 (32%) included information on their official coronavirus disease 2019 website. Most states identified authorized retailers (n = 37; 79%), provided information about pickup/delivery (n = 31; 66%), and stated the SNAP online start date (n = 29; 62%). About a quarter of states (n = 12; 26%) provided information about nutrition and health.

Conclusions and Implications

State communication about the SNAP online pilot mostly focused on basic program and retailer information and included limited information about nutrition and health.

Key Words: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, online shopping, grocery, nutrition education, COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the largest federal nutrition assistance program.1 In 2019, 35.7 million income-eligible Americans—almost half of them children—received SNAP benefits each month, equivalent to an average of $129 per person per month.2 The SNAP provides nutrition benefits to supplement the food budget of income-eligible families and authorizes more than 245,000 brick-and-mortar retailers across the country in which Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) allows SNAP participants to pay for food using SNAP benefits.3 However, disparities in the availability of healthy foods and beverages in high-poverty areas have posed challenges for many SNAP participants4 , 5 and may contribute to disparities in diet quality and health outcomes.6 To address these inequities, improve food security, and modernize SNAP, the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79) authorized the USDA to conduct a pilot to test the feasibility of allowing authorized SNAP retailers to accept SNAP benefits online.7 By 2017, the USDA selected 8 retailers (ie, Amazon, Dash's Market, Fresh Direct, Hy-Vee, Safeway, ShopRite, Walmart Stores, and Wright's Markets) in 8 states (ie, Alabama, Iowa, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Washington) for the year pilot.8 In parts of New York state, the SNAP online pilot began in April 2019, with plans to expand the program to 7 additional states in 2020.8

In the 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115-334) Congress required nationwide implementation of online acceptance for SNAP benefits after these pilots were implemented. This post-pilot nationwide implementation timeline rapidly changed in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, increased demand for online grocery shopping options given concerns about in-person shopping because of viral exposure, and increased food insecurity—particularly among communities of color.9, 10, 11 Indeed, during the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity increased from 10.5% of US households in 201912 to an estimated 23% of US households between April and May of 2020.13 This resulted in rapid increases in SNAP enrollment, which approached 43 million in April 20202 and is expected to remain high during the COVID-19 recovery.14 Online grocery ordering and sales have also surged, with as high as 79% of customers reporting online shopping, compared with 39% before COVID-19.15 , 16 In April, 2020, USDA used its Congressional authority to rapidly expand the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot; by August, 2020, 46 states and the District of Columbia (hereafter referred to as 47 states) had applied and been approved to participate in the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot,8 and by November, 2021, 5 of the 8 original retailers (ie, Amazon, Safeway, ShopRite, Walmart Stores, and Wright's Markets) continued to participate in online SNAP retail, whereas additional retailers engaged in the approval and testing process.17

All states provide information about SNAP to the general public through online platforms such as state agency websites and social media.18 Communication and outreach can improve SNAP participation, increase awareness of program changes, and provide information about how to access healthy and nutritious foods, potentially resulting in benefits for participants, states, and communities.19 , 20 However, the rapid expansion of the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot—particularly among states that were not online before COVID-19—may result in communication gaps that could lead to the underuse of this innovative program. The purpose of this study was to systematically assess state communication following SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot approval, with the goal of identifying emerging best practices and areas for improvement.

METHODS

Sample

All states and DC (n = 47) approved to participate in the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot by the end of October, 2020 were included in the study sample (as of August, 2021, 47 states and DC were actively participating; 1 state—Arkansas—had been approved but remained in the planning phase; as of manuscript submission/publication, 47 states and DC were actively participating).8 Review by the Institutional Review Board was not required for this study because human subjects were not involved.21 Using protocols established in similar state-based reviews,18 , 22 a systematic web-based search was conducted (details can be found in the Supplementary Materials associated with this article) to identify 3 primary information sources from each state: (1) official state program announcements for the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot (eg, press releases, declarations, official communications from state governor's offices); (2) state SNAP agency administrative sites (eg, Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance; Mississippi Department of Human Services); and (3) state government COVID-19 information sites. Exploratory data collection included searches among state agency social media (ie, Facebook, Twitter).

Coding Protocol

The USDA SNAP State Outreach Plan Guidance19 and the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) report SNAP Online: A Review of State Government SNAP Websites 18 were used to help identify relevant information sources and prior communication activities. Two trained coders (C.G.D. and C.B.) familiar with protocols established in similar state-based reviews conducted data collection and an initial review of 10 states to compare sources, extraction strategies, and open-ended coding notes to develop consensus and initial coding items (ie, meaningful portions of text) and domains (ie, groups of closely related items) using a conventional content analysis approach.23 This approach allowed coders the flexibility to use both inductive and deductive approaches in parallel, drawing from what was known about state SNAP agency communication policies (ie, from the USDA SNAP State Outreach Plan Guidance and the CBPP report) and what was learned from the data. Coders met with the larger research team to refine coding classifications (ie, dichotomous assessment for the presence or absence of an item) and formalize domains and definitions.

Using the initial coding protocol, 4 domains were identified and comprised 8 items (detailed definitions included in the Supplementary Materials associated with this article): (1) program information—SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot start date, SNAP eligibility, and SNAP enrollment information; (2) retailer information—online SNAP-authorized retailer identification, online retailer access, information about fees (eg, delivery fees) or minimum purchasing requirements (ie, USDA regulations state that “no minimum dollar amount per transaction or maximum limit on the number of transactions shall be established,” but retailers may include a suggested, not required, minimum24), and information about grocery pickup or delivery; (3) health and nutrition information such as tools or educational materials for making healthy choices; and (4) communication accessibility, which focused on the translation of communication materials into multiple languages.

When state government sources did not include information about the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot, additional information about SNAP enrollment, eligibility, and health and nutrition were not assessed. States generally include information about SNAP eligibility and enrollment on their official SNAP agency site; however, interest in the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot expansion made it necessary to focus data collection efforts on states that included this information in SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot materials. Therefore, information about eligibility or enrollment is only included if state SNAP agency sites included information about the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot.

One coder (C.B.) continued to identify and collect web-based communication among states who reported enrollment in the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot. Links to all communication materials and copies of documents were collected weekly from official state press releases, state SNAP administrating agency websites, and state emergency COVID-19 websites through the end of August, 2020. Following the establishment of domains and items, coders independently assessed communication materials and maintained consistent note-taking during the analytic process to document any clarifications made to codes and the process for re-examining and applying these clarifications to previously coded material. Questions about ambiguities in the coding process were discussed with the research team as a means of peer debriefing.25 Consensus coding was conducted through duplicate review (conducted by C.G.D.) and discussion. Disagreements in the application of codes were discussed, and a final code was applied in lieu of calculating interrater reliability.

Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) was used to organize data and extracted online text findings from sources. Across states, frequencies were calculated for each item (0, no information provided; 1, information available), and the frequency of items by the source was identified (defined as the number of state sources that included each item, divided by the number of states participating in the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot; n = 47).

RESULTS

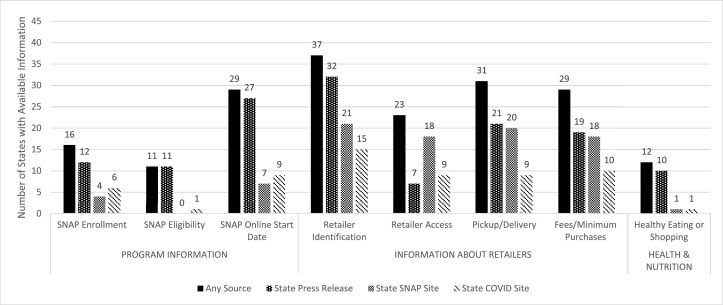

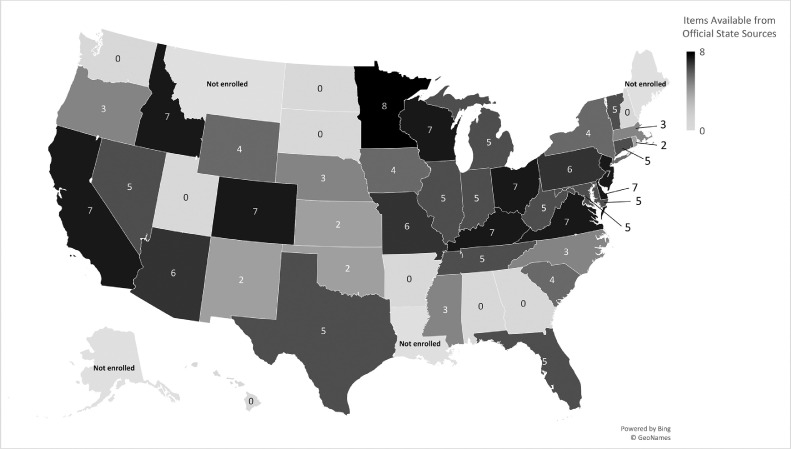

Figure 1 summarizes the frequency for all domains and items, overall and by source (additional details are included in the Supplementary Materials associated with this article). Thirty-four of 47 states (72%) issued an official press release accessible via an online search using SNAP-related keywords (n = 15; 32% were made available in multiple languages). Twenty-one states (45%) included some form of information about the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot on the SNAP agency official website (13 states, 28%) made this information available in multiple languages), and 15 (32%) included this information on their official state COVID-19 information page (n = 9 states,19% made this information available in multiple languages). Figure 2 provides a spatial overview of the results, indicating some regional patterns in the comprehensiveness of reporting (eg, states in the southeastern and Midwest US generally provided less information). Information about the comprehensiveness of reporting from each source is included in the Supplementary Materials associated with this article.

Figure 1.

Official state sources providing information about the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot.

Note: Forty-seven states (including Washington, DC) received approval to participate in the SNAP online pilot program as of October, 2020. Multiple sources from 1 state may report information for each item. Source counts from state press releases, state SNAP agency sites, and state emergency coronavirus disease 2019 sites may not sum to the total for any source. For each set of bars, the states can be counted multiple times if they provide information from multiple sources. The 3 bars on the right do not necessarily add up to the total. The full codebook is included in the Supplementary Materials associated with this article. Fees refer to additional charges applied to online purchases made using SNAP (eg, delivery fees, processing fees). The US Department of Agriculture regulations state that “no minimum dollar amount per transaction or maximum limit on the number of transactions shall be established,” but retailers may include a suggested, not required, minimum. This code applies to statements about the regulation or information about suggested minimum purchases.24

Figure 2.

The comprehensiveness of reporting for 8 coding criteria, by state (n = 47 states including Washington DC).

Program Information

Thirty-one of 47 states (66%) provided at least 1 aspect of program information regarding the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot. The start dates were most commonly available, which was reported for 29 states (62%) and was most often in the state press releases (n = 27; 57%) followed by state SNAP agency sites (n = 7; 15%) and state COVID-19 sites (n = 4; 9%). Among states that communicated information about the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot, 16 (34%) also included information about program enrollment (n = 12 press releases [26%]; n = 6 state COVID-19 sites [13%]; n = 4 state SNAP agency sites [9%]) and 11 included information about program eligibility (n = 11 press releases [23%]; n = 1 state COVID-19 sites [2%]; n = 0 state SNAP agency sites [0%]).

Information About Retailers

Thirty-seven states (79%) included some information about retailers including identifying those authorized to accept SNAP benefits online. This information was included in at least 1 resource for each state (n = 32 press releases [68%]; n = 15 state COVID-19 sites [32%]; n = 21 state SNAP agency sites [45%]). Information about grocery pickup or delivery was available for 31 states (66%; n = 21 press releases [45%]; n = 20 state COVID-19 sites [43%]; n = 9 state SNAP agency sites [19%]); 29 (62%) included information about fees or minimum purchases (n = 19 press releases [40%]; n = 10 state COVID-19 sites [21%]; n = 18 state SNAP agency sites [38%]), and 23 (49%) provided information about retailer access like information directions for how to enter SNAP EBT information into the online retailer portal or a link to this information, provided by the retailer (n = 7 press releases [15%]; n = 9 state COVID-19 sites [19%]; n = 18 state SNAP agency sites [38%]).

Health and Nutrition

Health and nutrition information was less frequently available, and no states made this information available from more than 1 source. Twelve states (26%) include some information about health or nutrition (n = 10 press releases [21%]; n = 1 state COVID-19 sites [2%]; n = 1 state SNAP agency sites [2%]); but this information was generally a generic restatement of SNAP's purpose (eg, “to encourage the consumption of healthy, nutritious foods”). No states provided additional information like a link or reference to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) program, which is a federal program dedicated to helping SNAP participants eat healthy on a limited budget,26 or links to resources to assist SNAP participants in making healthy choices when shopping virtually.

State Social Media (Exploratory)

Twenty-eight state SNAP agencies (60%) had a social media post announcing the approval of the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot, which typically included a link to official state or USDA resources or a local news story. Information about the state SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot was not accompanied by additional nutrition or health-related sources.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to systematically assess how states communicate publicly about the rapid SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot expansion during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and what information they provided. The content, source, and comprehensiveness of communication varied widely. Most states commonly included retailer information and seldomly provided information about health or nutrition. The variation in state communication is similar to findings from previous investigations of SNAP resources available online18 , 27 and recent state-based assessments of COVID-19 focused communication of school meal provision during the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic.22 The quality of the communications by states regarding the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot was likely impacted by the simultaneous implementation of other COVID-19 pandemic relief responses, including distributing the increased SNAP benefit allotments to eligible households; responding to increased SNAP enrollment during an unprecedented economic downturn; rolling out other innovative COVID-19 responses including Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer, which is administered by state SNAP agencies and provided eligible children in SNAP and non-SNAP households benefits during school closures; and implementing a variety of other SNAP administrative flexibilities.28 Understanding states’ approaches (ie, content, communication channel) to communicating critical program information is important to emergency planning efforts during public health emergencies or rapid program changes and may address food insecurity, limit health risk, and prevent the exacerbation of health disparities, particularly among underserved communities.

Almost all states identified retailers in their official state communication, most often in the official state press release or SNAP agency site. Although the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot has expanded almost nationwide, retailers authorized to accept SNAP benefits online was largely limited to 2 major retailers (ie, until November 2, Amazon and/or Walmart were the only retailers authorized to operate in 41 of the pilot states, details included in the Supplementary Materials associated with this article) though only 5 of the 8 original retailers continued to participate in the SNAP online program.8 , 17

Easy-to-find programmatic information about the pilot, including state SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot start date, eligibility, and enrollment information, were also inconsistently available, as evidenced by the fact that 44% of states did not provide any this information in their official state communications. Although most state SNAP agency websites included information about eligibility and enrollment on their general SNAP site (eg, online applications, eligibility screeners, and printable applications), state SNAP agency sites rarely included this type of information alongside announcements about the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot.18 The economic consequences of COVID-19 have increased SNAP eligibility, and households that are newly eligible (ie, those who have not previously participated in the program) may lack the background, experience, or tools to easily navigate the nutrition safety net. Clear communication from official sources to help newly eligible households interact with and navigate unfamiliar systems may be particularly needed in light of early-pandemic reports detailing confusion and disinformation about SNAP eligibility29 and research suggesting that SNAP participants prefer clear, consistent, and accessible messaging.27 This includes being transparent about how the revised public charge rule under the Trump administration included SNAP participation for the first time as part of its criteria for assessing admissibility as a US citizen but did not include the USDA Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer, and other school-based and childcare based programs. The Biden administration rescinded this revised public charge rule.30 , 31 , 32

Despite increasing efforts to strengthen the public health impacts of SNAP and the recent expansion of SNAP-Ed into innovative obesity prevention approaches,33 information about health and nutrition was largely absent from official state sources. When present, this information was typically generic and did not provide specific information or tools for shoppers to use in the online marketplace. Online communication from trusted sources can improve information access and may improve outcomes among high-risk communities.34 Although not included in this analysis, the inclusion of complementary outreach efforts such as phone calls, emails, and SNAP-Ed materials in future dissemination guidelines could be important.

This nationwide assessment provides timely insights on an unprecedented rollout of SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot expansion, but this study has limitations. First, these analyses are limited to web-based information and do not include systematic evaluation of communication sent to current SNAP participants by mail, email, phone, or text, and state social media accounts related to state SNAP agencies were considered exploratory. Second, data collection was limited to state-based government sources, which does not capture media coverage of state SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot communication efforts or communication between individuals via social media, among other potential key influencer sources. Third, data were collected in summer 2020, following USDA SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot approval for each state, and was updated throughout the short study period. Because some states began participation later in the study timeline—with additional time to prepare for their state's enrollment—it is possible that their communication efforts may appear more comprehensive. Finally, because of the focus on the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot, the assessment of a state's web-based information on SNAP eligibility and enrollment might be a limited representation of their potential overall web-based communication approach on these topical areas. However, this information has been well-documented and is available elsewhere.18

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the rapid expansion of SNAP Online has been a critical resource for participants to get access to food while maintaining social distancing. State outreach efforts to inform households about availability, eligibility, procedures, and resources about SNAP Online are important for helping participants navigate the program.19 Findings from this research report demonstrate that official state government communication and outreach resources to SNAP participants provided limited information about the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot. Communication mostly focused on basic program and retailer information with limited information about nutrition and health, which suggest some possible areas of inquiry for practice and research.

In addition to identifying retailers authorized to accept SNAP benefits online, more states may consider providing information about grocery pickup or delivery and fees or purchase requirements as these may be differentially available across states, retailers, and urban vs rural areas. Transparent communication requirements from Congress, the USDA, and states regarding these potential additional fees have tremendous potential to help households with low income avoid unexpected charges.

With respect to practice, this study found that health and nutrition information (eg, information about SNAP as a tool to access nutritious foods, resources to encourage healthy shopping online) was the least consistently addressed domain across all states and all types of communication. This suggests that efforts to provide more health and nutrition information to SNAP participants in the online environment may be useful for promoting nutrition security (which refers to consistent access, availability, and affordability of foods and beverages that promote well-being and prevent disease, particularly among our nation's most socially disadvantaged populations35). State SNAP agencies, SNAP-Ed programs, and nutrition professionals working with vulnerable populations (ie, communities of color, rural, and neighborhoods with high levels of SNAP participation) can play a role in addressing these gaps through the development and testing of policy, systems, and environmental interventions and informational materials for this new virtual marketplace.23 Online grocery shopping has the potential to improve nutrition by prompting or nudging customers toward healthier purchases; providing important nutrition information like the Nutrition Facts panel or healthy recipes; and by improving healthy food access in underserved areas and using culturally tailored approaches to maximize benefit uptake and use, beyond providing education.22 These efforts could be important because they move beyond direct education and strive to address the historical, systemic, and structural challenges that impact access and behavior. Further work could also explore how states can provide culturally and contextually relevant tips for how SNAP participants can best use online retailers to maximize health and nutrition and differences in communication strategies or effectiveness.

With respect to research, more work is needed to understand the most effective approaches to delivering nutrition information to SNAP participants in the online setting and how to best nudge these customers toward healthier purchases.36 Further work could also explore how states can provide culturally and contextually relevant tips for how SNAP participants can best use online retailers to maximize nutritious choices. Finally, ongoing assessments of state communication about SNAP online, with a particular focus on health and nutrition information, would complement existing guidance such as the SNAP Online: A Review of State Government SNAP Websites 18 and provide important insights about changes in communication strategies.

The rapid expansion of SNAP Online provided a resource to SNAP participants during COVID-19. However, the limited focus on health and nutrition information and limited types of communication channels suggest room for improvement—a shift that may help to promote nutrition security.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All authors are members of the Healthy Eating Research (HER)/Nutrition and Obesity Policy Research and Evaluation Network (NOPREN) COVID-19 School Nutrition Implications Working Group. HER is a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. NOPREN is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity Cooperative Agreement no. 5U48DP00498-05. HER provided stipend support to Sheila Fleischhacker as Co-Chair of the Working Group, and NOPREN provided fellowship support to Caroline Glagola Dunn. Cali Bianchi was supported by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have not stated any conflicts of interest. The views expressed in this report by Drs Dunn, Fleischhacker, and Bleich are solely the personal views of those authors.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2021.07.004.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Facts about SNAP.https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/facts. Accessed September 24, 2020.

- 2.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. SNAP data tables.https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap. Accessed September 24, 2020.

- 3.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Where can I use SNAP EBT?https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/retailer-locator. Accessed September 3, 2019.

- 4.Hilmers A, Hilmers DC, Dave J. Neighborhood disparities in access to healthy foods and their effects on environmental justice. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1644–1654. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho C, Volpe R. US Department of Agriculture; 2017. Independent Grocery Stores in the Changing Landscape of the US Food Retail Industry. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015;34:1830–1839. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benyshek D, Chino M, Dodge-Francis C, Begay T, Jin H, Giordano C. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in urban American Indian/Alaska Native communities: the Life in BALANCE pilot study. J Diabetes Mellitus. 2013;3:184–191. doi: 10.4236/jdm.2013.34028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Agriculture. FNS launches the Online Purchasing Pilot.Food and Nutrition Service.https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/online-purchasing-pilot. Accessed September 24, 2020.

- 9.Repko M. As coronavirus pandemic pushes more grocery shoppers online, stores struggle to keep up with demand. CNBC.https://www.cnbc.com/2020/05/01/as-coronavirus-pushes-more-grocery-shoppers-online-stores-struggle-with-demand.html. Accessed September 24, 2020.

- 10.Wolfson JA, Leung CW. Food insecurity during COVID-19: an acute crisis with long-term health implications. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1763–1765. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morales DX, Morales SA, Beltran TF. Racial/ethnic disparities in household food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationally representative study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00892-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Food security in the United States: key statistics and graphics.https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx. Accessed March 15, 2021.

- 13.Schanzenbach DW, Pitts A. How Much Has Food Insecurity Risen? Evidence from the Census Household Pulse Survey. Institute for Policy Research Rapid Research Report; 2020.https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/reports/ipr-rapid-research-reports-pulse-hh-data-10-june-2020.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2021.

- 14.Feeding America . Feeding America; 2020. The Impact of the Coronavirus on Food Insecurity. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redman R. Online grocery sales to grow 40% in 2020. Supermarket News.https://www.supermarketnews.com/online-retail/online-grocery-sales-grow-40-2020. Accessed March 15, 2021.

- 16.Leone LA, Fleischhacker S, Anderson-Steeves B, et al. Healthy food retail during the COVID-19 pandemic: challenges and future directions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020:17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Agriculture. USDA expands access to online shopping in SNAP, invests in future WIC opportunities.https://www.fns.usda.gov/news-item/fns-001820. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 18.Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. SNAP Online: a review of state government SNAP websites.https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-online-a-review-of-state-government-snap-websites. Accessed September 24, 2020.

- 19.US Department of Agriculture . Food and Nutrition Service; 2017. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): State Outreach Plan Guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stacy B, Tiehen L, Marquardy D. US Department of Agriculture; 2018. Using a Policy Index to Capture Trends and Differences in State Administartion of USDA's Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services. Human subject regulations decision charts. Office for Human Research Protections.https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/decision-charts/index.html#c1. Accessed September 24, 2020.

- 22.McLoughlin GM, Fleischhacker S, Hecht AA, et al. Feeding students during COVID-19-Related school closures: a nationwide assessment of initial responses. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020;52:1120–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2020.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Providing benefits to participants. 7 CFR §274.2 (2020).

- 25.Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2001;11:522–537. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Department of Agriculture . USDA, Food and Nutrition Service; 2018. Supplemental nutrition assistance program education (SNAP-Ed)https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/snap-ed Accessed September 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urdapilleta O, Kone A, Mbwana K, DeFever R, Hoesly L, Ehrich K. LLC for the US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2021. Understanding the Use of SNAP Online Applications. Prepared by Summit Consulting. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bleich SN, Dunn C, Fleischhacker S. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Healthy Eating Research; 2020. The Impact of Increasing SNAP Benefitson Stabilizing the Economy, Reducing Povertyand Food Insecurity Amid COVID-19 Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 29.WUSA9. VERIFY: Claim that anyone, regardless of income, can get food stamps in Maryland is false.https://www.wusa9.com/article/news/verify/verify-posts-claiming-anyone-regardless-of-income-can-get-food-stamps-in-maryland-right-now-are-false/65-91a7baf4-fe34-4554-802b-8cdaf0ebb707. Accessed September 24, 2020.

- 30.Bleich SN, Fleischhacker S. Hunger or deportation: implications of the Trump Administration's proposed public charge rule. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2019;51:505–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Citizenship and Immigration Services. Public charge fact sheet.https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-processes-and-procedures/public-charge. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- 32.Federal Register. Public charge ground of inadmissibility.https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/08/23/2021-17837/public-charge-ground-of-inadmissibility. Accessed August 30, 2021.

- 33.Bleich SN, Moran AJ, Vercammen KA, et al. Strengthening the public health impacts of the supplemental nutrition assistance program through policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:453–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2013. Health Literacy the Solid Facts. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mozaffarian D, Fleischhacker S, Andrés JR. Prioritizing nutrition security in the US. JAMA. 2021;325:1605–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hingle MD, Shanks CB, Parks C, et al. Examining equitable online federal food assistance during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): A case study in 2 regions. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4:nzaa154. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzaa154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.