Abstract

Introduction

Medical students’ attendance at lectures, particularly in the preclinical years, has been steadily declining over the years. One of the many explanations offered for this observation is that students have different learning styles and approaches, such that not all of them benefit from attending lectures; however, no studies have specifically examined this possibility. While there is evidence against learning styles as affecting objective measures of learning, they are associated with subjective measures of learning and may therefore influence student behavior. We hypothesized that students’ learning styles and/or approaches influence their views about the value and purpose of lectures and their motivation to attend them, which, in turn will affect their behavior.

Materials and Methods

A LimeSurvey was distributed to all preclinical students at the American University of Beirut. The survey included questions about demographic data, self-reported attendance rates in Year 1 of medical school, two validated and standardized questionnaires assessing the students’ learning styles (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, tactile, group, individual) and learning approaches (superficial, deep, strategic), and a series of questions exploring the students’ views about the purpose and value of lectures and their motivation to attend lectures.

Results

No associations were found between learning styles or approaches and attendance rates, but this may have been confounded by the mandatory attendance policy at the time. There were, however, a few positive associations between some learning styles or approaches and the students’ views about the value of attending lectures. In particular, students with high scores as auditory learners tended to see absolutely no value in attending lectures, and those with high scores as group, auditory or visual learners, tended to see less value in taking their own notes in lectures. Students with superficial approaches to learning felt that watching videos of a lecture provides equivalent education to attending a lecture. There were no statistically significant associations with either the perceived purpose of lectures or the motivation to attend lectures after correction for multiple testing.

Conclusions

This study reveals that except for some interesting findings related to auditory learners, differences in learning styles or approaches among students cannot adequately explain differences in their attitudes, and likely, behavior, regarding lecture attendance. The idea that learning styles and approaches can influence educational preferences and outcomes, while attractive and intuitive, continues to require supporting evidence.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40670-021-01362-3.

Keywords: Medical students, Classroom, Attendance, Learning styles, Learning approaches

Introduction

Didactic lectures have long served as the primary method by which medical students are taught, particularly in the preclinical years. Student attendance at lectures has been steadily declining over the years however, and this has become a concern for many institutions and faculty [1–3]. Several explanations have been offered for this decline; these include the practice by many schools of recording lectures and making them available to students, the plethora of electronic resources on the Web, along with a shift in educational approaches to emphasize more student-centered and self-directed learning rather than passive learning [4–10]. This has led many medical schools to ease the policies on student attendance, making it optional rather than mandatory. Some schools like the Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont have even elected to totally eliminate lectures from the curriculum [11].

Despite the currently dominant discourse portraying lectures as obsolete methods of passive learning, several academics have voiced their objections to this maligning of lectures, expressed mainly in mainstream media, with opinion pieces bearing revealing titles such as: “In praise of the lecture” or “In defense of the lecture” [12–16]. Indeed, some studies have demonstrated that non-attendance of lectures correlates with a decline in academic performance [17–20], which lends support to those arguments. Some schools have opted for a hybrid problem-based learning (PBL) system, where lectures supplement PBL sessions in the early transition, and are part of scaffolds that will allow students to eventually become full self-learners [21]. For educators implementing this type of curriculum, lecture attendance may be essential in order to ensure the success of the PBL curriculum. Alternatively, some studies suggested that a flipped classroom approach (whereby lectures are replaced by active in-class activities preceded by advance self-study) results in better learning outcomes compared with traditional lecture-based teaching [22, 23]. A recent meta-analyses and a systematic review, however, concluded that there is a lack of strong evidence in support of flipped classrooms, and, at best, minimal gains in student knowledge compared with lectures [24, 25].

In order to understand student behavior, reconcile differing opinions, and recommend appropriate policies and courses of action, investigators have explored the factors that affect medical students’ attendance practices. These studies examined the students’ attitudes toward attendance policies, their views regarding the value and purpose of lectures, what motivates them to attend, and whether non-attendance is a reflection of unprofessionalism [20, 26–30]. Results revealed that the reasons why students attend lectures include a desire to increase their scores, take their own notes, know what to focus on, and have the chance to ask questions. The inefficiency of lectures within large overcrowded halls, the availability of recorded lectures, and previous negative experience with the lecturer — or “bad” lecturing — were among the reasons for not attending [29]. Furthermore, it is clear that students do not have uniform views about lectures, and that, in general, their views misalign with those of faculty [1–3]. Interestingly, one theme that came up in several studies but was not sufficiently or systematically explored is that students opt to attend activities that suit their learning preferences [20, 26, 27, 29].

Students’ learning styles have been proposed as important considerations in developing student-centered curricula and instituting multiple learning modalities [31–35]. Reid classified learning styles into six different modalities: (1) visual learners, who prefer to study by using visual aids, e.g., reading and studying charts; (2) auditory learners, who prefer to listen to lectures or audiotapes; (3) kinesthetic learners, who prefer to learn by the experience of the subject matter; (4) tactile learners, who prefer to learn by “doing,” e.g., experiments or building models; (5) individual learners, who prefer to learn alone; and (6) group learners, who prefer to learn in groups [36]. Numerous studies were conducted to characterize medical students’ learning styles [37–40]. None of these studies, however, went beyond description to try to correlate learning styles with any particular outcome, and there is scant evidence for the claims made about learning styles and their relevance to actual learning or student outcomes [41, 42]. In contrast, there is accumulating evidence for the lack of relevance of learning styles to any objective outcome of learning [43–48]. As a result, several educators have called for abandoning the “myth” of learning styles [49, 50]. One interesting study, however, was quite revealing: Knoll et al. [51] showed that although learning styles do not influence any objective measure of learning (e.g., test performance), it was associated with subjective aspects of learning such as metacognition; specifically, they found one aspect of metacognitive judgment — judgment of learning — to be correlated with learning styles. Thus, learning styles may influence how students perceive their own learning and how they judge what is best for them; thus, it may influence their decisions to attend or not attend lectures.

Students have also been differentiated according to their learning approaches, as deep, strategic, or superficial learners [52–55]. As such, deep learners place an emphasis on understanding concepts and relating ideas, while superficial learners achieve surface learning with emphasis on memorization. Strategic learners use either deep or superficial learning as appropriate, and their main objective is to achieve the highest possible grades. In contrast to the case with learning styles, several studies have shown a correlation between both deep and strategic learning strategies and academic success [56–58].

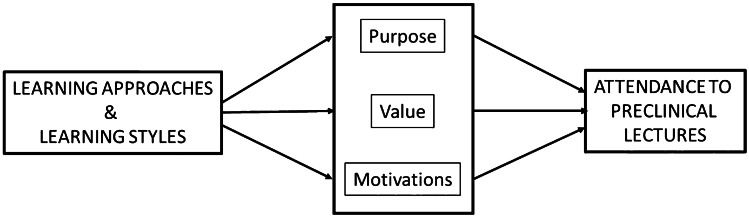

We hypothesized that medical students’ attitudes and behavior regarding attendance at lectures is influenced, if not determined, by their learning style and/or approaches. Establishing this would not only explain their behavior, but also would influence curricular structure and offerings as well as policy development by medical schools. We employed the conceptual framework shown in Fig. 1, whereby learning styles and approaches influence students’ views about the value and the purpose of lectures and their motivation to attend them; this in turn will affect their behavior. In order to test this hypothesis, we first attempted to study the relationship between learning styles or approaches and attendance rates directly. However, since at the time of the study there was a mandatory attendance policy requiring 60–80% attendance rates at our institution, student behavior may not have been a true reflection of their views and attitudes. Hence, we also assessed the relationship between learning styles, learning approaches, and the students’ views about the purpose and value of lectures and their motivation to attend them.

Fig. 1.

Proposed conceptual framework of the factors influencing students’ attendance to preclinical lectures

Methods

This study employed an anonymous, online survey (LimeSurvey version 2, Hamburg, Germany) and was approved by the American University of Beirut (AUB) Institutional Review Board (IRB). The LimeSurvey was developed and stored on the AUB server. All questions were optional. The IRB’s approved email invitation script and informed consent were posted before the start of the survey. Subjects who wished to participate accessed the survey link and filled in their answers. In order to ensure anonymity, participants were not asked to sign anything, or to provide any personal identifiers.

Target Population

This research concerns large-scale didactic lectures, the majority of which are provided during the first 2 years of the AUB Faculty of Medicine (AUBFM) medical curriculum. Therefore, students who were either first (N = 113) or second (N = 105) year medical students were targeted.

The medical degree (MD) program at AUBFM follows the American model and consists of 4 years of undergraduate medical education. The requirements for admission include a bachelor degree and completion of core premedical courses including biology, chemistry, physics, English language, humanities, and social sciences. The preclinical curriculum has a short foundational phase followed by an integrated organ system-based approach. Additional courses include those concerned with medical humanities, social medicine and global health, medical ethics, clinical skills, and learning communities dedicated to personal and professional development. Learning in the preclinical years is multimodal and includes lectures, team-based learning, interdisciplinary sessions, laboratories, case-based learning, and hands-on practice. Small group learning is emphasized. Assessments include multiple choice questions, observed structured clinical examinations, essays, direct observation, and multisource feedback. The two clinical years are hospital or ambulatory-based clinical clerkships.

Measurements

Students were asked to fill a demographics section, and to estimate the frequency of their attendance at didactic lectures in Year 1 of medical school. Following that, they had to fill 5 short surveys about the following: their views on the value of lectures, the purpose of lectures, their motivation to attend lectures, their learning styles, and their learning approaches.

For the first 3 surveys, the questions were developed based on an extensive literature search [1, 20, 28–30, 59] and insight from the authors’ experience as active members of the AUBFM curriculum committee (authors RS and NKZ) and as medical students (authors AE, AA, JRH, AAN and GF). The survey was then polished based on feedback from members of the AUBFM Program for Research and Innovation in Medical Education (PRIME), which included faculty and staff involved in education (https://www.aub.edu.lb/fm/medicaleducation/Pages/PRIME.aspx).

The survey on the value of lectures required students to indicate their level of agreement with 7 statements; five of these statements indicated a positive value for lectures (i.e., they understand better when they take their own notes, lectures put students in a learning mind frame, allow them to achieve better grades, allow long term retention, and have a learning value beyond exam performance), and two items indicated a negative view of the value of lectures (i.e., lectures are of absolutely no value; lectures can be replaced by videos). In addition, the students were asked to rank order 7 statements relating to the purpose of lectures and 8 statements relating to their motivations to attend (Appendix).

Concerning the two other sections, students were instructed to complete two widely used and validated instruments with 1–5 Likert scale questions: an 18-item short version of the Approaches and Study Skills Inventory for Students (ASSIST) questionnaire that reveals their learning approaches being deep, strategic, or superficial (52;53) and a 30-item preferred learning style questionnaire that determines their learning styles being visual, tactile, auditory, group, kinesthetic, or individual [36].

Data Collection and Analysis

The survey was launched on March 13, 2018 with three reminders sent at least 1 week apart. Responses were then exported from the LimeSurvey to SPSS (v. 24, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) followed by data cleaning, merging, and coding.

The learning approaches and styles were scored as per guidelines (36;52;53). There are six questions for each of the three learning approaches; the maximum score per strategy is hence 30. As for the learning styles, five individual questions contribute to each of the six learning styles; hence, the maximum score per learning style is 25 (Appendix). Cronbach’s alpha values were computed for assessment of reliability.

Data are presented as numbers with frequencies or means ± standard deviation of the mean (SD) as appropriate. Categorical data were compared using the Fisher-Exact test. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analyses or bivariate Pearson’s correlations were performed for the associations with the scores of the learning strategies and styles as applicable. Results were corrected for multiple testing. As such, a statistically significant P value was set as less than 0.05/7 = 0.00714 with seven being the number of associations performed for each of the learning preferences scale (i.e., style or approaches).

Results

Baseline Demographics and Attendance Rates

One hundred and eighty-nine students responded to the survey. Of those, 112 (RR = 99%) were first year medical students while 77 (RR = 73.3%) were second year medical students. Ninety-eight (53.5%) were males and eighty-five (46.5%) were females, a gender distribution that is representative of the distribution in both classes.

When asked about their attendance at didactic lectures in the first year of medical school, 28 (14.9%) reported frequently attending lectures (attending more than 75% of lectures), 132 (70.8%) reported moderate attendance (i.e., attending between 25 and 75% of lectures), while 28 (14.9%) reported rarely attending lectures (i.e., attending less than 25% of classes), 16 of whom never attended lectures.

Associations of Students’ Learning Styles and Approaches with Attendance Rates

The scores of students on most of the learning styles and approaches had a relatively high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha values were ≥ 0.65 except for visual learning: Table 1), and the students’ response to the individual questions of each instrument is shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. There were no significant differences among the various scores for the different learning styles. In contrast, AUB medical students had different scores concerning learning approaches, with the highest scores for deep learning, followed by strategic learning, and the lowest scores for superficial learning (P < 0.001 among all 3 groups). There were no differences in the scores for any of the learning styles or approaches among the groups of students with high, moderate, and low attendance rates.

Table 1.

Scores of AUB medical students in various learning approaches and learning styles in relation to their self-reported attendance rates

| All | Attendance to medicine 1 lectures | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Low < 25% of lectures |

Moderate 25–75% of lectures |

High > 75% of lectures |

P valueb | ||||||

| N | Mean ± SD | P valuea | Cronbach’s α | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Learning approaches | |||||||||

| Deep | 139 | 23 ± 4 | 0.696 | 23 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | 23 ± 4 | 0.997 | ||

| Strategic | 149 | 22 ± 6 | 0.797 | 22 ± 4 | 22 ± 5 | 21 ± 6 | 0.737 | ||

| Superficial | 141 | 18 ± 5c,d | < 0.0001 | 0.715 | 18 ± 3 | 19 ± 5 | 17 ± 6 | 0.397 | |

| Learning styles | |||||||||

| Visual | 131 | 23 ± 7 | 0.395 | 23 ± 5 | 23 ± 7 | 20 ± 7 | 0.160 | ||

| Tactile | 130 | 23 ± 9 | 0.664 | 23 ± 6 | 24 ± 9 | 21 ± 10 | 0.459 | ||

| Auditory | 127 | 22 ± 8 | 0.663 | 23 ± 9 | 21 ± 7 | 24 ± 10 | 0.431 | ||

| Group | 128 | 24 ± 10 | 0.758 | 27 ± 11 | 24 ± 9 | 22 ± 9 | 0.247 | ||

| Kinesthetic | 127 | 23 ± 9 | 0.663 | 24 ± 6 | 23 ± 9 | 22 ± 10 | 0.808 | ||

| Individual | 130 | 24 ± 8 | 0.243 | 0.639 | 24 ± 8 | 24 ± 8 | 24 ± 6 | 0.900 | |

aP values by one-way ANOVA comparing the scores of all students on the 3 learning approaches and on the 6 learning styles

bP values by one-way ANOVA comparing scores on learning strategies and learning styles among the students with low, moderate and high attendance rates

cP < 0.0001 compared with “Deep”

dP < 0.0001 compared with “Strategic”

Since there was a mandatory attendance policy at the time, this might have influenced student behavior and confounded the relationship between learning style/strategy and attendance behavior. Therefore, we next assessed the students’ views about lectures and tried to correlate them to both attendance rates and learning styles and approaches.

Associations Between Students’ Views on the Value of Attending Lectures and Attendance Rates

There was a significantly higher degree of agreement with all 5 statements suggesting a positive value of lectures among students who had high attendance rates (Table 2). Thus, significantly more of the students who frequently attend lectures believed that (1) they understand better when they take their own notes (83.4% vs. 41.7%), (2) lectures put them in a learning mode or mind frame (68.0% vs. 12.5%), (3) lectures help them achieve better grades (52.0% vs. 4.2%), (4) lectures improve long term retention (60.0% vs. 20.8%), and (5) there is a learning value to attending lectures not reflected in exam performance (76.0% vs. 33.4%).

Table 2.

Distribution of students according to their self-reported attendance rates in relation to their views about the value of attending lectures

| Attendance to medicine 1 lectures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL |

Low < 25% of lectures |

Moderate 25–75% of lectures |

High Bullet 75% of lectures |

P value | ||

| I understand better when I take my own notes during lectures | Disagree | 23 (13.1) | 8 (33.3) | 13 (10.2) | 2 (8.3) | 0.007 |

| Neither | 30 (17.1) | 6 (25.0) | 22 (17.3) | 2 (8.3) | ||

| Agree | 122 (69.7) | 10 (41.7) | 92 (72.5) | 20 (83.4) | ||

| Lectures put me in a learning mode or mind frame | Disagree | 44 (25.0) | 15 (62.5) | 25 (19.7) | 4 (16.0) | < 0.001 |

| Neither | 34 (19.3) | 6 (25.0) | 24 (18.9) | 4 (16.0) | ||

| Agree | 98 (55.7) | 3 (12.5) | 78 (61.4) | 17 (68.0) | ||

| Lectures help me achieve better grades | Disagree | 60 (34.3) | 18 (75.0) | 34 (27.0) | 8 (32.0) | < 0.001 |

| Neither | 56 (32.0) | 5 (20.8) | 47 (37.3) | 4 (16.0) | ||

| Agree | 59 (33.7) | 1 (4.2) | 45 (35.7) | 13 (52.0) | ||

| Attending lectures improves long term retention | Disagree | 46 (26.1) | 13 (54.2) | 27 (21.3) | 6 (24.0) | 0.007 |

| Neither | 38 (21.6) | 6 (25.0) | 28 (22.0) | 4 (16.0) | ||

| Agree | 92 (52.3) | 5 (20.8) | 72 (56.7) | 15 (60.0) | ||

| There is a learning value to attending lectures not reflected in exam performance | Disagree | 35 (19.9) | 11 (45.8) | 19 (15.0) | 5 (20.0) | 0.002 |

| Neither | 35 (19.9) | 5 (20.8) | 29 (22.8) | 1 (4.0) | ||

| Agree | 106 (60.2) | 8 (33.4) | 79 (62.2) | 19 (76.0) | ||

| Lectures are absolutely of no value | Disagree | 127 (72.2) | 11 (45.8) | 97 (76.4) | 19 (76.0) | 0.029 |

| Neither | 30 (17.0) | 7 (29.2) | 20 (15.7) | 3 (12.0) | ||

| Agree | 19 (10.8) | 6 (25.0) | 10 (7.9) | 3 (12.0) | ||

| Watching videos of a lecture provides equivalent education to attending the lecture | Disagree | 21 (11.9) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (11.8) | 6 (15.8) | 0.013 |

| Neither | 27 (15.3) | 2 (8.3) | 18 (14.2) | 7 (18.4) | ||

| Agree | 128 (72.7) | 22 (91.7) | 94 (74.0) | 25 (65.8) | ||

Data are presented as N (%). Numbers do not add up to the total of 189 due to missing answers. P values were generated by the Fisher-Exact test

Despite these distinctions, it should be noted that the majority of students (72.2%) disagreed with the statement that “Lectures are of absolutely no value.” In addition, the majority of students believed that lectures put them in a learning mode or mind frame, that there is a learning value to attending lectures not reflected in exam performance, and that “watching videos of a lecture provides equivalent education to attending the actual lecture” (Table 2).

Associations Between Students’ Views on the Value of Attending Lectures and Their Learning Styles and Approaches

Students who had had significantly high scores as auditory learners disagreed with 4 out of the 5 positive statements on the value of attending lectures, but agreed that “lectures are of absolutely no value.” Students who had significantly higher visual, auditory, and group learning style scores disagreed with the statement “I understand better when I take my own notes during lectures” (Table 3).

Table 3.

Scores of students on the learning approaches and learning styles in relation to their views about the value of attending lectures

| I understand better when I take my own notes during lectures | Lectures put me in a learning mode or mind frame | Lectures help me achieve better grades | Attending lectures improves long term retention | There is a learning value to attending lectures not reflected in exam performance | Lectures are absolutely of no value | Watching videos of a lecture provides equivalent education to attending the lecture | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Learning approaches | ||||||||

| Deep | Disagree | 22 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | 23 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | 23 ± 3 | 23 ± 5 |

| Neither | 22 ± 4 | 25 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | 24 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | 23 ± 4 | 24 ± 3 | |

| Agree | 24 ± 4 | 23 ± 3 | 23 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | 24 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | |

| Strategic | Disagree | 21 ± 6 | 21 ± 4 | 22 ± 5 | 21 ± 5 | 22 ± 5 | 22 ± 5 | 24 ± 6 |

| Neither | 23 ± 4 | 23 ± 6 | 22 ± 5 | 22 ± 4 | 24 ± 3 | 22 ± 6 | 23 ± 4 | |

| Agree | 22 ± 5 | 22 ± 5 | 21 ± 6 | 22 ± 6 | 21 ± 6 | 22 ± 4 | 21 ± 5 | |

| Superficial | Disagree | 18 ± 6 | 19 ± 5 | 18 ± 5 | 18 ± 5 | 19 ± 4 | 18 ± 5 | 14 ± 5 |

| Neither | 19 ± 6 | 17 ± 5 | 19 ± 5 | 20 ± 4 | 19 ± 5 | 18 ± 6 | 18 ± 3 | |

| Agree | 18 ± 4 | 18 ± 5 | 17 ± 5 | 17 ± 5 | 18 ± 5 | 20 ± 5 | 19 ± 5a | |

| Learning styles | ||||||||

| Visual | Disagree | 27 ± 8 | 24 ± 8 | 23 ± 6 | 23 ± 7 | 24 ± 7 | 22 ± 7 | 23 ± 7 |

| Neither | 21 ± 6a | 22 ± 6 | 23 ± 7 | 22 ± 6 | 23 ± 7 | 22 ± 7 | 20 ± 6 | |

| Agree | 22 ± 6a | 22 ± 6 | 21 ± 7 | 22 ± 7 | 22 ± 6 | 25 ± 6 | 23 ± 7 | |

| Tactile | Disagree | 24 ± 9 | 23 ± 8 | 24 ± 8 | 24 ± 9 | 26 ± 8 | 22 ± 9 | 26 ± 9 |

| Neither | 23 ± 8 | 27 ± 7 | 23 ± 10 | 25 ± 9 | 22 ± 8 | 25 ± 8 | 19 ± 7 | |

| Agree | 23 ± 9 | 22 ± 10 | 23 ± 9 | 22 ± 9 | 22 ± 9 | 26 ± 7 | 24 ± 9 | |

| Auditory | Disagree | 28 ± 11 | 24 ± 10 | 25 ± 9 | 26 ± 10 | 26 ± 9 | 21 ± 7 | 25 ± 9 |

| Neither | 24 ± 7 | 26 ± 7 | 21 ± 6 | 22 ± 7 | 23 ± 8 | 23 ± 7 | 19 ± 7 | |

| Agree | 20 ± 7a | 20 ± 7 | 21 ± 8 | 20 ± 7a | 20 ± 7a | 30 ± 12a | 22 ± 8 | |

| Group | Disagree | 30 ± 10 | 23 ± 8 | 24 ± 10 | 25 ± 11 | 26 ± 12 | 24 ± 9 | 25 ± 10 |

| Neither | 26 ± 10 | 28 ± 12 | 24 ± 9 | 26 ± 11 | 25 ± 8 | 25 ± 11 | 22 ± 8 | |

| Agree | 23 ± 9 | 24 ± 9 | 26 ± 9 | 23 ± 8 | 24 ± 9 | 27 ± 13 | 25 ± 10 | |

| Kinesthetic | Disagree | 26 ± 10 | 24 ± 8 | 24 ± 9 | 25 ± 9 | 26 ± 8 | 22 ± 9 | 24 ± 10 |

| Neither | 21 ± 8 | 23 ± 7 | 22 ± 7 | 23 ± 9 | 22 ± 8 | 23 ± 7 | 18 ± 6 | |

| Agree | 23 ± 8 | 23 ± 9 | 23 ± 9 | 22 ± 8 | 22 ± 9 | 30 ± 9 | 24 ± 9b | |

| Individual | Disagree | 27 ± 9 | 25 ± 8 | 25 ± 9 | 25 ± 8 | 25 ± 8 | 23 ± 7 | 27 ± 8 |

| Neither | 24 ± 7 | 25 ± 9 | 24 ± 7 | 24 ± 8 | 24 ± 9 | 23 ± 8 | 20 ± 7 | |

| Agree | 23 ± 7 | 23 ± 7 | 23 ± 7 | 23 ± 7 | 23 ± 7 | 28 ± 9 | 24 ± 8 | |

Numbers in bold indicate P < 0.00714 by one-way ANOVA for the corresponding learning approach or learning style

aP < 0.00714 compared with “Disagree” Bonferroni post hoc comparison

bP < 0.00714 compared with “Neither” by Bonferroni post hoc comparison

As for learning strategies, student scores on deep, strategic, and superficial learning did not vary with their level of agreement with any of the statements describing the value of attending lectures except for one statement whereby students who scored higher on the superficial learning method considered that “watching videos of a lecture provides equivalent education to attending the lecture” (Table 3).

Associations Between Students’ Views on the Purpose of Lectures and Attendance Rates

When asked to rank propositions regarding the perceived purpose of lectures (Supplementary Table 3), students believed the most important purpose of lectures to be the presentation of all the information that students need, and the presentation of current research outside exam content. In contrast, allowing students to interact with and learn from the faculty’s personal experience ranked lowest, preceded by teaching students how to think about and solve problems after learning on their own. Notably, there were no significant associations between the ranking of the perceived purpose of lectures and attendance rates.

Correlations Between Students’ Views on the Purpose of Lectures and Their Learning Styles and Approaches

There were no statistically significant correlations between the students’ rankings of statements describing the purpose of lectures and neither their scores on learning approaches (Supplementary Table 4) nor learning styles after correction for multiple testing (Supplementary Table 5).

Associations Between Students’ Rankings of Their Motivations to Attend Lectures and Their Attendance Rates

When examining the ranking of the perceived motivations to attend lectures (Supplementary Table 6), “the lecturer makes frequent clinical correlations” ranked as the highest motivation to attend classes while the lecturer being an expert in the subject ranked lowest. Of note, there were no significant associations between the ranking of the perceived motivations to attend lectures and attendance rates.

Correlations Between Students’ Rankings of Their Motivations to Attend Lectures and Their Learning Approaches and Styles

When looking at whether the student rankings of the motivations to attend lectures varied according to their learning approaches’ scores, again, no statistically significant findings were revealed after correction for multiple testing (Supplementary Table 7), and the same applies to the different learning styles (Supplementary Table 8).

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that particular differences in learning styles and approaches may contribute in a very limited manner to differences in student attitudes toward lectures, and may help explain their behaviors. Our conceptual model proposed that the students’ attendance behavior is influenced by their perception of their learning styles and approaches, as proposed in the literature. To begin with, it was striking that most of our students did value lectures; yet, a large number of them do not attend as expected. We did not find a correlation between learning styles, or approaches, and attendance rates. This may either disprove our hypothesis, or, as suggested in the “Methods” section, may be a result of the confounding effect of the attendance policy at the time, which dictated that students must attend anywhere between 60 and 80% of lectures; otherwise, this would be considered a professional lapse and may result in some form of disciplinary action (a policy that has since been revoked). Thus, students may have been behaving out of duress and not in compliance with their attitudes and beliefs. It should be noted, here, that students were able to miss lectures because the attendance policy was not consistently enforced or applied; nevertheless, the policy remains a potential confounding variable. Another possible limitation is that attendance rates were self-reported by students and not objectively measured, and students may not have recollected these figures reliably resulting in a potential recall bias. Therefore, we decided to examine their attitudes and views about lectures, and determine whether those are affected by their learning styles and approaches.

It is clear from the results that students who frequently attend classes find a particular value in lectures; thus, their views on the value of lectures may be considered an indirect index of their behavior. Our results indicate that these views about the value of lectures are in turn correlated with some learning styles and approaches, most obviously, auditory learning styles, whereby students with high scores on auditory learning tend to see less value in attending lectures. Furthermore, students with high scores on visual, auditory, and group learning were significantly unlikely to find much value in taking their own notes.

It was interesting to note that those who agreed that watching videos provides the same value as attending a live lecture tended to have higher scores on superficial learning. One explanation may be that these students are only interested in memorizing facts, and not in the educational experience that engages them with other students, and with the professor in an interactive environment; this is supported by the inverse correlation between student score on superficial learning and the rank given to the lecturer being interactive as a motivating factor to attend.

In terms of the purpose of lectures and student motivations to attend lectures, it was revealing that group learners tended to value lectures that offer problem-solving opportunities while kinesthetic learners valued lectures that are interactive. Group learners, on the other hand, do not see taking their own notes (a solitary activity) as a valuable aspect of lectures. It was also understandable that superficial learners were not motivated by interactive lecturers since their main concern is to memorize and not go deep into the material. In contrast to the preceding, there were some observations that could not be explained easily, e.g., why auditory learners do not value lectures that present current research findings. In addition, we were pleasantly surprised that students valued lectures where instructors present research outside of exam material (which is an expectation at our institution), since our general impression from interacting with students was that they were overloaded with information, and as such, primarily interested in learning just enough to pass examinations.

It should be noted that although these were interesting associations for both the purpose of lectures and the motivation to attend lectures, the magnitude of the correlations was small — with a correlation coefficient not more than 0.21, and the statistical significance was lost after correction for multiple testing for all of them. Thus, the relationships and conclusions drawn, although indicating a trend, need further supporting evidence. The only other available study to address the same question was performed with physiology students and found no relationship between student learning styles and attendance behavior [44].

One factor that may explain the weak correlations we observed is that, as Ojeh et al. [38] showed, students are actually unaware of their learning styles as assessed by the survey instruments, and thus may privilege other perceived learning style considerations when deciding to attend lectures. In addition, other student considerations play a role in deciding whether or not to attend lectures. For example, a study among students of medicine, pharmacy, nursing, and dentistry found that external factors, such as the need to catch up on sleep and distance of residence from school, were the most prominent factors in student absenteeism [29]. These factors may conceivably play a larger role than learning styles or approaches in determining students’ attendance behavior.

How do the results of this study impact educational practices? While the idea that instruction should be tailored to student learning styles, and that this provides better learning outcomes to students, may be intuitive and reasonable, there is a glaring deficiency of studies to provide evidence for this contention [41, 42]; while students may have different abilities and preferences, there is no evidence to imply that they will learn better if instructed in a particular manner. This gap was partly filled in a recent article by Husmann and O’Loughlin [43] who found that there was no correlation between any particular learning style and assessment outcomes. Our study further explored the significance of learning styles and approaches and provides evidence for a very limited influence of learning styles and strategies on the attitudes and, possibly, behaviors of students regarding attendance of lectures. The magnitude of the relationships and the sporadic nature of the associations preclude making recommendations for specific curricular structures or changes. This is yet another “nail in the coffin of learning styles” borrowing from the title of Hussman and O’Loughlin’s study.

Conclusions

Although it is clear that students value lectures, they selectively attend lectures. Hence, the information on students’ beliefs about the value and purpose of lectures and their motivations to attend them is important in order to reconcile the expectations and needs of the faculty and the students, and to develop curricula, policies, and approaches that meet the learning needs of the latter. This study reveals that, except for some interesting findings related to auditory learners, differences in learning styles or approaches among students cannot adequately explain differences in their attitudes, and likely, behavior, regarding lecture attendance. The idea that learning styles and approaches can influence educational preferences and outcomes, while attractive and intuitive, still lacks evidence to support it.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank students who responded to the LimeSurvey.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ramzi Sabra, Email: rsabra@aub.edu.lb.

Nathalie K. Zgheib, Email: nk16@aub.edu.lb

References

- 1.Zazulia AR, Goldhoff P. Faculty and medical student attitudes about preclinical classroom attendance. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(4):327–334. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2014.945028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Persky AM, Kirwin JL, Marasco CJ, May DB, Skomo ML, Kennedy KB. Classroom attendance: factors and perceptions of studens and faculty in US schools of pharmacy. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2014;6:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2013.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruth-Sahd LA, Schneider MA. Faculty and student perceptions about attendance policies in baccalaureate nursing programs. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2014;35(3):162–166. doi: 10.5480/13-1105.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettit RK, McCoy L, Kinney M. What millennial medical students say about flipped learning. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:487–497. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S139569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans KH, Ozdalga E, Ahuja N. The medical education of generation Y. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(2):382–385. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer JA, Jordan RK. Learner centred approaches in medical education. BMJ. 1999;318(7193):1280–1283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7193.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta NB, Hull AL, Young JB, Stoller JK. Just imagine: new paradigms for medical education. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1418–1423. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a36a07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prober CG, Khan S. Medical education reimagined: a call to action. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1407–1410. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a368bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prober CG, Heath C. Lecture halls without lectures–a proposal for medical education. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(18):1657–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han H, Resch DS, Kovach RA. Educational technology in medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(Suppl 1):S39–S43. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.842914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine. Active learning. https://www.med.uvm.edu/mededucation/about/activelearning_new 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- 12.Tokumitsu M. In defense of the lecture. Jacobin magazine. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/02/lectures-learning-school-academia-universities-pedagogy/ 2017 February 26 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- 13.Small A. In defense of the lecturer. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/In-Defense-of-the-Lecture/146797 2014 May 27 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- 14.Furedi F. In praise of the university lecture and its place in academic scholarship. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2013/dec/10/in-praise-of-academic-lecture 2013 December 10 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- 15.Kotsko A. A defense of the lecture. Inside Higher Education. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2009/11/20/defense-lecture 2009 November 20 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- 16.Fulford AA, Mahon A. A philosophical defence of the traditional lecture. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/philosophical-defence-traditional-lecture 2018 April 28.

- 17.Demir EA, Tutuk O, Dogan H, Egeli D, Tumer C. Lecture attendance improves success in medical physiology. Adv Physiol Educ. 2017;41(4):599–603. doi: 10.1152/advan.00119.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramaniam B, Hande S, Komattil R. Attendance and achievement in medicine: investigating the impact of attendance policies on academic performance of medical students. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(2):202–205. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.113662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deane RP, Murphy DJ. Student attendance and academic performance in undergraduate obstetrics/gynecology clinical rotations. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2282–2288. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisen DB, Schupp CW, Isseroff RR, Ibrahimi OA, Ledo L, Armstrong AW. Does class attendance matter? Results from a second-year medical school dermatology cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(7):807–816. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moro C, Mclean M. Supporting students' transition to university and problem-based learning. Med Sci Educ. 2017;27:353–361. doi: 10.1007/s40670-017-0384-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson HG, Jr, Frazier L, Anderson SL, Stanton R, Gillette C, Broedel-Zaugg K, et al. Comparison of pharmaceutical calculations learning outcomes achieved within a traditional lecture or flipped classroom andragogy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(4):70. doi: 10.5688/ajpe81470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belfi LM, Bartolotta RJ, Giambrone AE, Davi C, Min RJ. "Flipping" the introductory clerkship in radiology: impact on medical student performance and perceptions. Acad Radiol. 2015;22(6):794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gillette C, Rudolph M, Kimble C, Rockich-Winston N, Smith L, Broedel-Zaugg K. A meta-analysis of outcomes comparing flipped classroom and lecture. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(5):6898. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen F, Lui AM, Martinelli SM. A systematic review of the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in medical education. Med Educ. 2017;51(6):585–597. doi: 10.1111/medu.13272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Billings-Gagliardi S, Mazor KM. Student decisions about lecture attendance: do electronic course materials matter? Acad Med. 2007;82(10 Suppl):S73–S76. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31813e651e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattick K, Crocker G, Bligh J. Medical student attendance at non-compulsory lectures. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2007;12(2):201–210. doi: 10.1007/s10459-005-5492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmed T, Shaheen A, Azam F. How undergraduate medical students reflect on instructional practices and class attendance: a case study from the Shifa College of Medicine. Pakistan J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:7. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bati AH, Mandiracioglu A, Orgun F, Govsa F. Why do students miss lectures? A study of lecture attendance amongst students of health science. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(6):596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta A, Saks NS. Exploring medical student decisions regarding attending live lectures and using recorded lectures. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):767–771. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.801940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olanipekun T, Effoe V, Bakinde N, Bradley C, Ivonye C, Harris R. Learning styles of internal medicine residents and association with the in-training examination performance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koohestani HR, Baghcheghi N. A comparison of learning styles of undergraduate health-care professional students at the beginning, middle, and end of the educational course over a 4-year study period (2015–2018) J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:208. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_153_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Childs-Kean L, Edwards M, Smith MD. Use of learning style frameworks in health science education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020 Jul;84(7):ajpe7885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Lau JN. A commentary on teaching and learning styles as fueled by 'how learning preferences and teaching styles influence effectiveness of surgical educators'. Am J Surg. 2021;221(2):254–255. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh P, Owen PA, Mustafa N, Beech R. Learning and teaching approaches promoting resilience in student nurses: an integrated review of the literature. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020 May;45:102748. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Reid JM. The learning style preferences of ESL students. TESOL Quaterly. 1987;21(1):87–111. doi: 10.2307/3586356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lujan HL, DiCarlo SE. First-year medical students prefer multiple learning styles. Adv Physiol Educ. 2006;30(1):13–16. doi: 10.1152/advan.00045.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ojeh N, Sobers-Grannum N, Gaur U, Udupa A, Majumder MAA. Learning style preferences: a study of pre-clinical medical students in Barbados. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2017;5(4):185–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarabi-Asiabar A, Jafari M, Sadeghifar J, Tofighi S, Zaboli R, Peyman H, et al. The relationship between learning style preferences and gender, educational major and status in first year medical students: a survey study from iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015 Jan;17(1):e18250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Urval RP, Kamath A, Ullal S, Shenoy AK, Shenoy N, Udupa LA. Assessment of learning styles of undergraduate medical students using the VARK questionnaire and the influence of sex and academic performance. Adv Physiol Educ. 2014;38(3):216–220. doi: 10.1152/advan.00024.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pashler H, McDaniel M, Rohrer D, Bjork R. Learning styles: concepts and evidence. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2008;9(3):105–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rohrer D, Pashler H. Learning styles: where's the evidence? Med Educ. 2012;46(7):634–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Husmann PR, O'Loughlin VD. Another nail in the coffin for learning styles? Disparities among undergraduate anatomy students' study strategies, class performance, and reported VARK learning styles. Anat Sci Educ. 2019;12(1):6–19. doi: 10.1002/ase.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horton DM, Wiederman SD, Saint DA. Assessment outcome is weakly correlated with lecture attendance: influence of learning style and use of alternative materials. Adv Physiol Educ. 2012;36(2):108–115. doi: 10.1152/advan.00111.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Constantinidou F, Baker S. Stimulus modality and verbal learning performance in normal aging. Brain Lang. 2002;82(3):296–311. doi: 10.1016/S0093-934X(02)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massa LJ, Mayer RE. Testing the ATI hypothesis: should multimedia instruction accomodate verbalizer-visualizer cognitive style? Learn Individ Differ. 2006;16:321–336. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2006.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rogowsky BA, Calhoum BM, Tallal P. Matching learning style to instructional method: effects on comprehension. J Educ Psychol. 2015;107(1):64–78. doi: 10.1037/a0037478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cook DA, Thompson WG, Thomas KG, Thomas MR. Lack of interaction between sensing-intuitive learning styles and problem-first versus information-first instruction: a randomized crossover trial. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14(1):79–90. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newton PM. The learning styles myth is thriving in higher education. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1908. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirschner PA. Stop propagating the learning styles myth. Comput Educ. 2017;106:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knoll AR, Otani H, Skeel RL, Van Horn KR. Learning style, judgements of learning, and learning of verbal and visual information. Br J Psychol. 2017;108(3):544–563. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Entwistle NJ, Waterson S. Approaches to studying and levels of processing in university students. Br J Educ Psychol. 1988;58:258–265. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1988.tb00901.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Speth CA, Namuth DM, Lee DJ. Using the ASSIST short form for evaluating an information technology application: validity and reliability issues. Informing science journal. 2007;10:107–116. doi: 10.28945/459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mirghani HM, Ezimokhai M, Shaban S, van Berkel HJ. Superficial and deep learning approaches among medical students in an interdisciplinary integrated curriculum. Educ Health (Abingdon ) 2014;27(1):10–14. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.134293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chonkar SP, Ha TC, Chu SSH, Ng AX, Lim MLS, Ee TX, et al. The predominant learning approaches of medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1122-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferguson E, James D, Madeley L. Factors associated with success in medical school: systematic review of the literature. BMJ. 2002;324(7343):952–957. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feeley AM, Biggerstaff DL. Exam success at undergraduate and graduate-entry medical schools: is learning style or learning approach more important? A critical review exploring links between academic success, learning styles, and learning approaches among school-leaver entry ("traditional ") and graduate-entry ("nontraditional") medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(3):237–244. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1046734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baykan Z, Nacar M. Learning styles of first-year medical students attending Erciyes University in Kayseri. Turkey Adv Physiol Educ. 2007;31(2):158–160. doi: 10.1152/advan.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Samarakoon L, Fernando T, Rodrigo C. Learning styles and approaches to learning among medical undergraduates and postgraduates. BMC Med Educ. 2013;25(13):42. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.