Abstract

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)1 heterozygous gain‐of‐function (GOF) mutations are known to induce immune dysregulation and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMCC). Previous reports suggest an association between demodicosis and STAT1 GOF. However, immune characterization of these patients is lacking. Here, we present a retrospective analysis of patients with immune dysregulation and STAT1 GOF who presented with facial and ocular demodicosis. In‐depth immune phenotyping and functional studies were used to characterize the patients. We identified five patients (three males) from two non‐consanguineous Jewish families. The mean age at presentation was 11.11 (range = 0.58–24) years. Clinical presentation included CMCC, chronic demodicosis and immune dysregulation in all patients. Whole‐exome and Sanger sequencing revealed a novel heterozygous c.1386C>A; p.S462R STAT1 GOF mutation in four of the five patients. Immunophenotyping demonstrated increased phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription in response to interferon‐α stimuli in all patients. The patients also exhibited decreased T cell proliferation capacity and low counts of interleukin‐17‐producing T cells, as well as low forkhead box protein 3+ regulatory T cells. Specific antibody deficiency was noted in one patient. Treatment for demodicosis included topical ivermectin and metronidazole. Demodicosis may indicate an underlying primary immune deficiency and can be found in patients with STAT1 GOF. Thus, the management of patients with chronic demodicosis should include an immunogenetic evaluation.

Keywords: demodex, demodicosis, gain‐of‐function, immune dysregulation, STAT‐1

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)1 gain‐of‐function (GOF) mutations are known to induce immune dysregulation. Immune phenotyping of these patients presenting with Demodex infection is lacking. Here, we summarize an in‐depth immune analysis of 5 patients with STAT1 GOF from 2 non‐consanguineous families presenting with chronic demodicosis. Thus, management of chronic demodicosis should include the evaluation of an underlying primary immune deficiency disorder.

INTRODUCTION

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)1 gain‐of‐function (GOF) heterozygous mutations are known to induce immune dysregulation and increased susceptibility to infections [1]. Over‐expression of phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription (pSTAT)‐1 results in exaggerated interferon (IFN)‐γ reaction and eventually impaired T helper (Th) type 17 differentiation [2].

Various reports demonstrate a wide clinical spectrum consisting of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMCC), immune dysregulation, poly‐autoimmunity such as autoimmune thyroiditis and cytopenia and increased susceptibility to viral, mycobacterial and bacterial infections. Infections vary in severity, ranging from mild infections to severe John Cunningham virus‐induced progressive multi‐focal leukoencephalopathy [1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7].

Demodex is a parasitic mite that affects humans and dogs. In humans, infections with Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis are reported to induce chronic blepharitis and facial eruptions in both immune‐competent and immune‐deficient patients [8]. The immune mechanism underlying demodicosis is not completely understood. Pathways induced by Demodex spp. involve activation of regulatory T cells (Tregs), Th9 and cytotoxic T cells (CTL) via human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I. Down‐regulation of Toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐2 is also reported, suggesting that there are joint adaptive and innate immune responses against the mite [9].

Recent reports of patients with STAT1 GOF mutations detailed a dermatological phenotype of chronic demodicosis [10, 11, 12, 13]. However, in‐depth immune characterization of these patients is lacking.

In this study, we present our experience with a cohort of five patients from two different pedigrees presenting with facial and ocular demodicosis. These patients were found to have STAT1 GOF mutations and exhibited a complex phenotype consisting of immune dysregulation, CMCC and demodicosis. We summarize our experience and review the corresponding literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This is a retrospective analysis of patients with immune dysregulation who presented with infections with Demodex spp. Patients were treated from 2018 to 2020 at Hadassah‐Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel. All patients were diagnosed with STAT1 GOF by genetic analysis and functional immune studies.

Immune phenotyping

Lymphocyte subpopulation analysis

Standard‐of‐care immune work‐up was clinically guided and conducted at the Sheba Tel‐Hashomer primary immune deficiency (PID) Laboratory, Ramat‐Gan, Israel. For analysis of cell surface markers, whole blood in ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) was lysed using red blood cell lysis buffer (BD Pharm Lyse; BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA). Cell‐surface staining was then conducted using antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19 and CD56 (Beckman Coulter, Brea, California, USA). Measurement and analysis were performed using flow cytometry (NAVIOS; Beckman Coulter) and Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter).

Quantification of regulatory T cells

For the detection of forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3), the cells were fixed/permeabilized using a FoxP3 staining buffer set, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, eBioscience, San Diego, California, USA). The antibodies used were CD4‐VioBlue, CD25‐antigen‐presenting cells (APC) (both from Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, California, USA) and FoxP3‐fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA).

Phosphorylated STAT‐1 and IL‐17 analyses

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from the patients and healthy controls were either left untreated or stimulated with interferon (IFN)‐α (40 000 unit/ml; PBL Assay Science, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA) for 15 min at 37ºC. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with PerFix‐EXPOSE reagents (Beckman Coulter) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and stained with anti‐CD3‐phycoerythrin‐cyanin (PC7), anti‐CD4‐APC, anti‐CD8‐Pacific Blue, anti‐CD45‐Krome orange (all from Beckman Coulter) and anti‐STAT‐1‐Alexa Fluor 488 (BD Biosciences) antibodies.

For the expression of interleukin (IL)‐17, PBMCs from the patients and healthy controls were stimulated for 12 h with 40 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma, St Louis, Missouri, USA) and 10−5 M ionomycin (Sigma) in the presence of 1μg/mL GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with PerFix‐nc reagents (Beckman Coulter) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and stained with anti‐CD3‐PC7 and anti‐IL‐17‐Pacific Blue antibodies (Beckman Coulter). The measurement and analysis were carried out using flow cytometry (NAVIOS; Beckman Coulter) and Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter).

T cell proliferation and TCR V‐β repertoire

T cell proliferation was tested by standard [3H]‐thymidine uptake assays (1 μCi/well) by culturing 105 PBMCs with phytohemagglutinin (PHA = 5 µg/ml; Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) or plastic bound anti‐CD3 (5 µg/mL OKT3; eBioscience, San Jose, California, USA) for 72 h. Sample radioactivity was measured using a liquid scintillation counter and the results were calculated as a percentage of normal controls. The analysis of T cell receptor (TCR) Vβ expression was determined according to the manufacturer’s manual (Beta Mark TCR Vβ Repertoire Kit; Beckman Coulter).

Genetic analysis

Whole‐exome sequencing (WES) was performed on genomic DNA samples from patient (P)1. Coding regions were enriched using the Twist Human Core Exome Plus Kit (Twist Bioscience, San Francisco, California, USA) on a NovaSeq 6000 sequencing machine (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The Illumina Dragen Bio‐IT Platform version 3.4.9 was used to align reads to the human reference genome (hg19) based on the Smith–Waterman algorithm [14], as well as to call variants based on the GATK variant caller version 3.7 [15]. Variant annotation was performed using KGG‐Seq version 1.1 [16]. Further annotation and filtration steps were performed by in‐house scripts using various additional data sets. The mutations found in STAT1 were validated by dideoxy Sanger sequencing, and familial segregation using genomic DNA of the patients and their first‐degree relatives was confirmed. Data were evaluated using Sequencer version 5.0 software (Gene Codes Corporation). P5 genetic diagnosis was previously reported by Molho‐Pessach et al [11].

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the patients

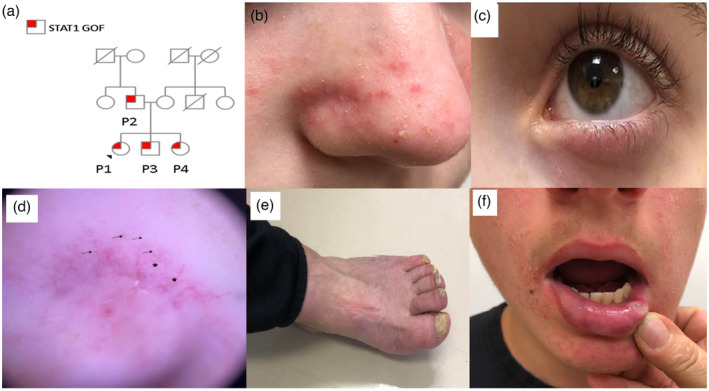

Clinical features of the patients are detailed in Table 1. The patient cohort includes five patients (three males and two females) from two non‐consanguineous Jewish families. P5 was previously reported by Molho‐Pessach et al [11]. The family pedigree of P1–P4 is presented in Figure 1a. The mean age at presentation was 11.11 (0.58–24) years.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with demodicosis and STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutation

| Patient* | Family | Ethnicity/ gender | Age at presentation/ current age (years) | STAT1 GOF mutation | Clinical presentation | Treatment | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune/inflammatory | Infectious | Allergic | Malignant | Other | |||||||

| 1 | A | J/F | 9/ 12 | Heterozygous missense mutation, Chr2: 191848428, NM_007315.3, c.1386C>A p.Ser462Arg, exon 17/25 | Autoimmune cytopenia, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | Chronic blepharitis, CMCC, UTI, chronic facial and ocular demodicosis | Atopic dermatitis | – | FTT, delayed puberty | Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, Fluconazole, IVIG; topical ivermectin; topical metronidazole | Alive |

| 2 | J/M | 15/46 | Chronic colitis | Angular cheilitis, chronic facial demodicosis Onychomycosis, nail Trichophyton, esophageal candidiasis, tinea corporis | – | – | – | Fluconazole; topical ivermectin; topical metronidazole; oral tetracyclines | Alive | ||

| 3 | J/M | 7 months/ 15 | Recurrent aphthous stomatitis | Recurrent URTI; chronic facial demodicosis, CMCC, UTI | – | – | – | Fluconazole; topical ivermectin | Alive | ||

| 4 | J/F | 7 / 7 | Recurrent aphthous stomatitis | UTI, CMCC, chronic facial demodicosis | – | – | – | Fluconazole | Alive | ||

| 5** | B | J/M | 24/47 | Heterozygous missense mutation, c.821G > A, R274Q | Recurrent aphthous stomatitis | Pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, CMCC, chronic facial demodicosis, group A streptococcal axillary skin abscess | – | Abdominal large B cell lymphoma, non–germinal center type | Retinitis pigmentosa, recurrent renal colic | Oral ivermectin Itraconazole, R–CHOP chemotherapy protocol [17]. | Alive |

J = Jews; F = female; M = male; STAT‐1 = signal transducer and activator of transcription 1; CMCC = chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis; UTI = urinary tract infection; GOF = gain‐of‐function; IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulins; FTT = failure to thrive.

Patients were born to non‐consanguineous families; **P5 was previously reported by Molho‐Pessach et al. [11].

FIGURE 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients. (a) Family pedigree of patients P1–P4. The family is non‐consanguineous. An autosomal dominant heterozygous mutation is noted in the father and his three children. (b) Facial erythematous papules and pustules, consistent with demodicosis, as well as erythematous scaly patches characteristic of seborrheic dermatitis in P1. (c) Chronic blepharitis in P1. (d) Dermoscopic examination of the facial skin of P1 showing Demodex ‘tails’ (arrows) and Demodex follicular openings (stars), as well as non‐specific scales. (e) Nail dystrophy and onychomycosis in P2. (f) Aphthous stomatitis in P3

Facial infections with Demodex spp. were noted in all patients on physical and dermoscopic examinations (Figure 1b,d, respectively). Chronic blepharitis was seen in P1 and P5 (Figure 1c). All patients had CMCC, including candida vulvovaginitis (P1 and P4) and severe esophageal candidiasis (P2). Nail dystrophy and onychomycosis were noted in P2 (Figure 1e). Other infectious manifestations consisted of urinary tract infections in three patients (P1, P3 and P4) and pleural infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in one (P5).

Four patients (P1–P4) had manifestations of immune dysregulation, including chronic colitis (P2), seborrheic dermatitis and atopic dermatitis (P1), autoimmune cytopenia (P1), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (P1) and recurrent aphthous stomatitis (P3, P4 and P5; Figure 1f).

P1 suffered from iron deficiency anemia and more than 1 year of intermittent epigastric pain with associated nausea and reflux. Her pain was exacerbated by eating. She had periods of intermittent diarrhea, with up to four loose stools daily, without blood or mucous. Work‐up included celiac serology in the presence of normal immunoglobulin (Ig)A levels and stool for infectious organisms and stool calprotectin, which were normal. She underwent endoscopy and colonoscopy for further evaluation. Visually, the mucosa appeared normal throughout. The gastric mucosa, however, was extremely friable and minimal manipulation with the endoscope caused diffuse gastric bleeding. Histology showed duodenal mucosa with disrupted villous architecture, marked active and chronic inflammation and cryptitis and gastric mucosa with erosions, severe chronic and active inflammation, cryptitis and disrupted glandular architecture. No infectious organisms or granulomas were present. Cytomegalovirus immunostaining was negative, as were silver and Ziehl–Neelsen staining.

P5 was recently found to have lymphadenopathy above and beneath the diaphragm with splenic involvement on positron emission tomography following presentation with constitutional symptoms. Pathology from the large retroperitoneal node demonstrated large atypical lymphoid cells, some of which have a prominent nucleolus. These stained strongly for CD20, paired box protein (PAX5) and multiple myeloma antigen 1 (MUM‐1) and weakly for B cell lymphoma 6 (Bcl‐6). He was diagnosed with stage III diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), non‐germinal center type.

Genetic work‐up

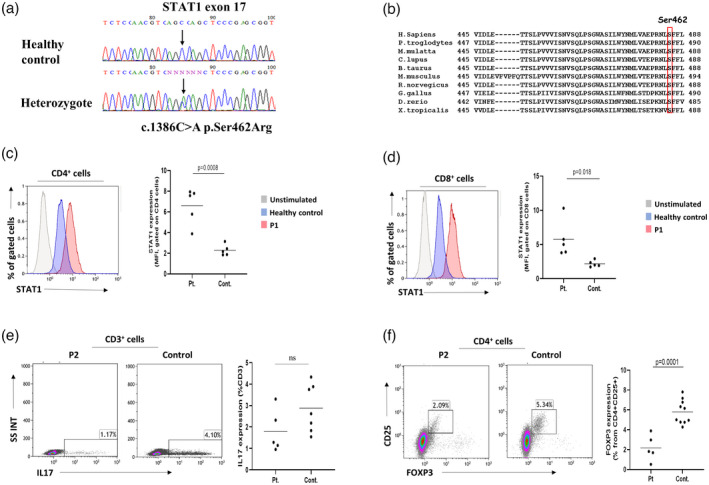

An underlying primary immune deficiency (PID) in P1–4 was suspected due to the combined presentation of chronic demodicosis, CMCC and immune dysregulation. Indeed, WES analysis revealed a novel GOF mutation in STAT1 (Figure 2a). A heterozygous missense mutation was noted in Chr2: 191848428 (Hg19), NM_007315.3, c.1386C>A; p.S462R. Serine 462 is evolutionarily conserved from man to frog (Figure 2b) and its substitution by arginine is rare and classified as probably pathogenic, based on the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines. P5 was previously reported to have a heterozygous STAT1 GOF‐inducing missense mutation (c.821G > A, R274Q) [11].

FIGURE 2.

Confirmation of STAT1 gain‐of‐function (GOF) in the patient cohort. (a) Whole‐exome sequencing analysis of patient 1 (P1) revealed a novel heterozygous STAT1 GOF‐causing missense mutation in Chr2: 191848428, NM_007315.3, c.1386C>A p.Ser462Arg, exons 17/25. (b) STAT1 GOF mutation is seen at a conserved site. (c) Flow cytometry analysis of CD3+ T cells representing levels of phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription (pSTAT‐1) following interferon (IFN)‐α stimulation. A significantly increased expression of pSTAT‐1 in CD4+ T cells of the patients, compared to healthy controls (HC), is compatible with STAT1 GOF (p = 0.0008). (d) Similar statistically significant over‐expression of pSTAT‐1 following IFN‐α stimulation is noted when gating on CD8+ T cells (p = 0.018). (e) Flow cytometry of interleukin‐17‐producing T cells demonstrating reduced levels in the patients compared to HC, although not statistically significant (p = 0.113). (f) Flow cytometry quantification of CD4+CD25+forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3)+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) identifying significantly low numbers in the patients compared to HC, correlating with immune dysregulation features seen in the cohort (p = 0.0001)

Immune analysis and confirmation of STAT‐1 GOF

Following the genetic findings, an in‐depth immune investigation was conducted. Absolute CD4+ and CD8+ T cell lymphopenia were noted in P1. T cell subset phenotyping yielded normal CD4+ and CD8+ populations in all other patients. Natural killer (NK) cell numbers were reduced in P2.

Decreased absolute B cell counts were seen in P1, P2 and P3. P1 also displayed an absence of specific antibody production to protein and polysaccharide vaccines, although the total IgG level was in the lower limit of the normal range. Anti‐thyroid peroxidase (TPO) autoantibody levels were increased in two patients (P1 and P5), further supporting immune dysregulation.

T cell proliferation was quantified by the use of a [3H]‐thymidine incorporation assay in response to CD3 stimuli and revealed reduced proliferation capacity in P2, P4 and P5.

Levels of pSTAT‐1 following interferon (IFN)‐α stimulation were significantly increased in all the patients compared with healthy controls (HC), both in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure 2c,d; p = 0.0008 and 0.018, respectively), thus confirming the diagnosis of STAT1 GOF. IL‐17‐producing T cells were also reduced in the patients, although not statistically significant (Figure 2e ; p = 0.113). Tregs were significantly low in the patients, compared with HC (Table 2; Figure 2f, p = 0.0001), compatible with the features of immune dysregulation seen in the cohort.

TABLE 2.

Immune work‐up of patients with STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutation

| Parameter | P1 (12 years) | P2 (46 years) | P3 (15 years) | P4 (7 years) | P5* (47 years) | Normal range | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7–8 years (Ig 6–8; IgE 7–8 years) | 9–13 years (Ig 9–10; IgE 9–12 years) | 14–18 Years (Ig>10; IgE 16–17 years) | >18 years (Ig>10; IgE>18 years) | ||||||||

| Absolute lymphocyte count (109/l) | 0.675 | 2.666 | 1.520 | 2.329 | 1.056 | 1.50–6.80 | 1.50–6.50 | 1.20–5.20 | 0.959–3.644 | ||

| Lymphocyte subpopulation** | T cells | CD3+ (109/l) | 0.641 | 2.506 | 1.155 | 1.863 | 0.813 | 1.36–2.74 | 1.07–2.27 | 1.09–2.6 | 0.700– 2.508 |

| CD4+ (109/l) | 0.398 | 1.413 | 0.715 | 0.955 | 0.475 | 0.66–1.61 | 0.64–1.29 | 1.450.56– | 0.464–1.721 | ||

| CD8+ (109/l) | 0.169 | 0.960 | 0.319 | 0.652 | 0.285 | 0.44–1.05 | 0.38–0.88 | 0.32–0.96 | 0.135–0.852 | ||

| CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs (% of cells) | 0.510 | 1.810 | 2.970 | 1.700 | 3.900 | 0.90–3.2 | 1–3.70 | 0.80–4.30 | 4.20–9.90 | ||

| NK cells | CD56+ (109/l) | 0.217 | 0.079 | 0.288 | 0.209 | 0.116 | 0.15–0.51 | 0.17– 0.53 | 0.15–0.7 | 0.082–0.594 | |

| B cells | CD19+ (109/l) | 0.013 | 0.037 | 0.106 | 0.279 | 0.095 | 0.2–0.68 | 0.17–0.63 | 0.14–0.56 | 0.092–0.515 | |

| Lymphocyte proliferation study (CPM; patient/ healthy control) | No mitogen | 247/323 | 403/292 | 389/483 | 221/483 | 272/483 | > 50% of control | ||||

| PHA6 | 61655/45285 | 30996/40738 | 49161/44336 | 52938/44336 | 32524/44336 | ||||||

| PHA25 | 101413/90538 | 57264/71587 | 50937/47224 | 66335/47224 | 42849/47224 | ||||||

| Anti‐CD3 | 14901/27728 | 2285/24350 | 33327/15590 | 6215/15590 | 4679/15590 | ||||||

| TCR versus beta repertoire | Normal/polyclonal | Polyclonal; single clone expansion | Normal/polyclonal | Normal/polyclonal | Normal/polyclonal | – | |||||

| Serum immunoglobulins*** | IgG (mg/dl) | 822 | 1165 | 1369 | 1541 | 1344 | 633–1280 | 608–1572 | 639–1349 | ||

| IgA (mg/dl) | 63 | 229 | 308 | 511 | 449 | 33–202 | 45–236 | 70–312 | |||

| IgM (mg/dl) | 92 | 161 | 154 | 327 | 33.20 | 48–207 | 52–242 | 56–352 | |||

| IgE (U/ml)+ | <25 | <25 | 47.50 | 140 | 68.20 | 2–403 | 2–696 | 2–537 | 2–214 | ||

| Specific IgG antibodies | VZV (AI) | Negative | 1.00 | NA | NA | Positive (2739 mIU/ml) | > 1.1 | ||||

| Measles (AI) | NA | 7.70 | 0.30 | 3.10 | Negative (5.82 IU/ml) | > 1.1 | |||||

| Rubella (IU/mL) | 7.58 | 70.67 | 36.52 | 73.26 | <3 | >30 | |||||

| Mumps (AI) | 0.30 | 3.00 | 0.70 | 2.00 | Negative (8 AU/mL) | >1.1 | |||||

| HBV surface (mU/mL) | Negative | Negative | 2.69 | 836.42 | 0 | >0.05 | |||||

| Diphtheria (IU/mL) | <0.01 | 0.33 | 0.97 | NA | 0.527 | >0.01 | |||||

| Tetanus (IU/mL) | 0.24 | 0.20 | 1.91 | NA | 0.03 | >0.51 | |||||

| Pneumococcal Ca Pol (mg/dL) | 1.60 | NA | 1.40 | 8.70 | NA | >2 | |||||

| Pertussis | 3.54 | 4.79 | 13.20 | 3.07 | NA | >55 | |||||

| EBV EBNA (U/mL) | 6.74 | 33.2 | >300 | >300 | Positive (4.96 S/CO) | >20 | |||||

| CMV (AU/mL) | 2.67 | >250 | <1.10 | 1.19 | 82 | >14 | |||||

| ANA | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | <1:100 | |||||

| Anti‐TPO (IU/mL) | 431.38 | <1.00 | <1.00 | 3.95 | 31 | 0‐5.6 | |||||

Tregs = regulatory T cells; FoxP3 = forkhead box protein 3; NK = natural killer; CPM = counts per minute; PHA = phytohemagglutinin; PHA6 = PHA 6 µg/ml; PHA25 = PHA 25 µg/ml; Ig = immunoglobulin; ANA = anti‐nuclear antibodies; anti‐TPO= anti‐thyroid peroxidase; HBV = hepatitis B virus; CMV = cytomegalovirus; Sm = anti‐smith antibody; VZV = varicella zoster virus; EBV = Epstein–Barr virus; EBNA = Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen. In bold type: values above normal range; italic type: below the normal range; NA = not applicable.

P5 was previously reported by Molho‐Pessach et al. (11) ; **age‐matched reference values for T cell subsets of pediatric and adult patients are taken from Gracia‐Prat et al. [40] and Apoil et al. [41] ;***age‐matched IgG, IgM and IgA reference ranges are taken from Jolliff et al. [42]; +age‐matched IgE reference ranges are taken from Martins et al. [43].

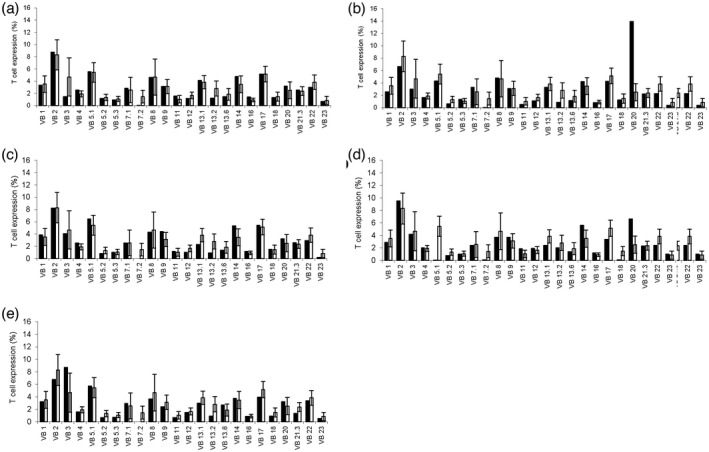

Examination of the TCR v‐β repertoire in the patient cohort demonstrated a normal polyclonal picture in P1, P3, P4 and P5 (Figure 3a,c–e, respectively). In P2, a single clonal expansion was notable (vβ 20), suggestive of the proliferation of an autoreactive T cell clone (Figure 3b).

FIGURE 3.

T cell receptor (TCR) V‐β repertoire of the patient cohort. (a,c–e) Examination of TCR v‐β repertoire in the patient cohort demonstrates a normal polyclonal phenotype in patients P1, 3, 4 and 5, respectively. (b) In P2, a single clone expansion is notable (vβ 20), suggestive of an autoreactive T cell clone proliferation

Treatment and outcome

All patients are currently alive, with a mean age of 25.4 (7–47) years. P5 was treated with prophylactic itraconazole; the others were prescribed fluconazole. Intravenous immunoglobulins replacement therapy and prophylactic trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole were commenced in P1, who displayed a combined immune phenotype of specific antibody deficiency and T cell lymphopenia. P1 was also treated with high‐dose omeprazole for her epigastric pain, with symptomatic improvement. Treatment with ruxolitinib was not approved by the patients’ respective medical insurance policies. P5 is currently completing treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R‐CHOP) chemotherapy for stage III diffuse large B cell lymphoma [17].

Facial demodicosis was treated with topical ivermectin 1% cream (P1–P3) and topical metronidazole 0.75% gel (P1 and P2). P2 was also treated with oral tetracyclines. P5 was treated with oral ivermectin for chronic blepharitis. All patients responded well to the above‐mentioned treatments, but the following cessation of treatment the findings reappeared.

DISCUSSION

STAT1 GOF is known to induce immune dysregulation, recurrent bacterial, viral and mycobacterial infections, as well as CMCC [3]. This study describes the functional immune characterization of five patients with STAT1 GOF mutations and demodicosis.

STAT1 GOF mutations are considered to have high penetration with a reported median age of disease onset of 1 year [3]. Although P3 from our study presented at the age of 7 months, median age at the onset of our cohort is 11.11 years. This discrepancy can be related to under‐diagnosed and overlooked symptoms and reduced awareness of the possible diagnosis of STAT1 GOF. Moreover, although the disease onset of patients with STAT1 GOF appears to be at infancy and early childhood, there are some reports of patients presenting at an older age, such as 14 [18] and 24 years [3].

Immune dysregulation is evident in our patients. Autoimmune manifestations, such as cytopenia and thyroiditis, correlated well with increased anti‐TPO autoantibody levels, the expansion of a single autoreactive T cell clone seen in P2 and low counts of Tregs. DLBCL in P5 and history of atopic dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis in P1 further strengthen the immune dysregulation features of our cohort. Interestingly, our patients had polyclonal TCR v‐β repertoires. However, the previously published report of nine patients with STAT1 GOF from China described a different phenotype with a skewed TCR diversity in most patients [19].

In addition to immune dysregulation, low IL‐17 production seen in our cohort is a known characteristic of STAT1 GOF and constitutes the underlying immune mechanism for CMCC via impaired STAT3‐dependent Th17 differentiation [2, 20, 21, 22].

P5 from our cohort was diagnosed with DLBCL. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first description of DLBCL in STAT1 GOF. Patients with STAT1 GOF were previously reported to have increased rates of malignancy, including squamous and gastrointestinal carcinomas [3]. However, the review of the literature yielded only one report of lymphoma in STAT1 GOF. Patients described were two family members with a T437N STAT1 GOF mutation presenting with Hodgkin’s lymphoma [23]. Thus, our study further emphasizes the unpredicted diversity of manifestations and disease course of STAT1 GOF.

Chronic demodicosis was not initially reported as a typical manifestation of STAT1 GOF in a large cohort of patients having this disorder [1]. Recently, four dermatological reports described chronic demodicosis in patients with STAT1 GOF mutations [10, 11, 12, 13]. Second et al. reported three family members with STAT1 GOF who presented with CMCC, chronic demodicosis, recurrent viral infections and poly‐autoimmunity, including hypothyroidism, type 1 diabetes mellitus, Sjögren’s syndrome and celiac disease. One of the patients had CD4+ and NK cell lymphopenia, as well as low IgM and IgG4 levels [12]. Studies by Sáez‐de‐Ocariz [13] and Baghad et al. [10] have described similar cohorts with prominent immune dysregulation, CMCC, rosacea, chronic demodicosis and blepharitis. However, none of the reports have shown an in‐depth immune characterization of the patients.

The T cell response appears to play a pivotal role in the immune defense against Demodex [9]. Indeed, a previous report of demodicosis in patients with STAT1 GOF suggested a plausible mechanism of reduced T cell function and subsequent Demodex proliferation [11]. Our study supports this assumption, with reduced T cell proliferation capacity seen in three patients in response to anti‐CD3 stimuli.

Interestingly, demodicosis was previously shown to induce Th17‐mediated inflammation. This was noted in patients with ocular demodicosis, who had increased levels of tear IL‐17 and IL‐12 [24]. Therefore, it appears that Th17 may play a role in the host‐defense response and also explain the increased susceptibility to demodicosis in STAT1 GOF.

P1 in our cohort demonstrated specific antibody deficiency. Hypogammaglobulinemia and impaired specific IgG production are not common in STAT1 GOF. However, there are several reports of patients with STAT1 GOF and humoral immune deficiency [25, 26, 27]. Suggested mechanisms include abnormal B cell differentiation [26] and reduced expression of CD25 on the B cell surface [27]. Although the exact role of humoral response in humans against Demodex is not entirely clear, high IgG‐secreting plasma cells were found in canine skin samples with demodicosis [9]. Therefore, it appears that the adaptive immune defense against demodicosis may consist of both humoral and cellular responses.

Our study is the first immune description of patients with STAT1 GOF who presented with chronic demodicosis. Chronic demodicosis may constitute a ‘red flag’ for an underlying PID. As shown in our report, demodicosis is probably an under‐recognized and overlooked manifestation of STAT1 GOF. Therefore, we propose that the diagnosis of demodicosis, specifically in the context of immune dysregulation and CMCC, should stimulate prompt immune and genetic work‐ups. These will allow early diagnosis and better genetic counseling to the patient’s family and facilitate treatment with ruxolitinib, which has been shown to have efficacy in STAT1 GOF [22, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33].

This study has several limitations. The cohort is small and the study is retrospective in design. Furthermore, demodicosis appears to modulate the innate immune system and specifically decrease TLR‐2 expression [34]. Our study is lacking in that it did not evaluate the innate immune systems of the patients. In addition, we did not have sufficient data in order to compare patients with STAT1 GOF with demodicosis with those without demodicosis. All the immune features presented in our cohort were previously described for patients with STAT1 GOF presenting without demodicosis [1, 6, 25, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39]. Moreover, due to the wide clinical spectrum of STAT1 GOF, we were not able to pinpoint specific immune characteristics that increase susceptibility to Demodex infections. Therefore, further studies of human cohorts, as well as murine models of STAT1 GOF, should be conducted in order to elucidate the specific immune pathways involved in the host defense against Demodex spp.

In conclusion, demodicosis is often overlooked by physicians, who treat the infection but fail to diagnose the underlying PID. We hope in this report to increase awareness of the association between STAT1 GOF and demodicosis. A collaborative effort between clinical immunologists and dermatologists is required in managing these patients. Prompt immune and genetic work‐up is essential and can facilitate better patient care and genetic counseling.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Oded Shamriz: treatment of patients, study design, immune work‐up and writing of the manuscript; Atar Lev and Raz Somech: immune work‐up and manuscript revisions; Amos J. Simon: immune and genetic work‐ups and manuscript revisions; Ortal Barel and Sigal Matza‐Porges: genetic work‐up; Adir Shaulov, Zev Davidovics, Ori Toker and Abraham Zlotogorski: treatment of patients and manuscript revisions; Vered Molho‐Pessach and Yuval Tal: treatment of patients, study design and supervision.

ETHICAL REVIEW

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hadassah Medical Center (number: HMO‐0370‐20).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study did not receive any specific funding.

Shamriz O, Lev A, Simon AJ, Barel O, Javasky E, Matza‐Porges S, et al. Chronic demodicosis in patients with immune dysregulation: An unexpected infectious manifestation of Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)1 gain‐of‐function. Clin Exp Immunol. 2021;206:56–67. 10.1111/cei.13636

Oded Shamriz and Atar Lev contributed equally and should be considered as first authors.

Vered Molho‐Pessach and Yuval Tal contributed equally and should be considered as last authors.

Contributor Information

Oded Shamriz, Email: oded.shamriz@mail.huji.ac.il.

Yuval Tal, Email: Yuvalt@hadassah.org.il.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available on request from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Depner M, Fuchs S, Raabe J, Frede N, Glocker C, Doffinger R, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 26 patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis due to gain‐of‐function mutations in STAT1. J Clin Immunol. 2016;36:73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okada S, Asano T, Moriya K, Boisson‐Dupuis S, Kobayashi M, Casanova JL, et al. Human STAT1 gain‐of‐function heterozygous mutations: chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and type I interferonopathy. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40:1065–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toubiana J, Okada S, Hiller J, Oleastro M, Lagos Gomez M, Aldave Becerra JC, et al. Heterozygous STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutations underlie an unexpectedly broad clinical phenotype. Blood 2016;127:3154–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meesilpavikkai K, Dik WA, Schrijver B, Nagtzaam NM, van Rijswijk A , Driessen GJ, et al. A novel heterozygous mutation in the STAT1 SH2 domain causes chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, atypically diverse infections, autoimmunity, and impaired cytokine regulation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zerbe CS, Marciano BE, Katial RK, Santos CB, Adamo N, Hsu AP, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in primary immune deficiencies: Stat1 gain of function and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:986–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eslami N, Tavakol M, Mesdaghi M, Gharegozlou M, Casanova JL, Puel A, et al. A gain‐of‐function mutation of STAT1: a novel genetic factor contributing to chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2017;64:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang MR, Zhao F, Wang S, Lv S, Mou Y, Yao CL, et al. Molecular mechanism of azoles resistant Candida albicans in a patient with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zomorodian K, Geramishoar M, Saadat F, Tarazoie B, Norouzi M, Rezaie S. Facial demodicosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:121–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gazi U, Taylan‐Ozkan A, Mumcuoglu KY. Immune mechanisms in human and canine demodicosis: a review. Parasite Immunol. 2019;41:e12673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baghad B, El Fatoiki FZ, Benhsaien I, Bousfiha AA, Puel A, Migaud M, et al. Pediatric demodicosis associated with gain‐of‐function variant in STAT1 presenting as rosacea‐type rash. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41:698–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molho‐Pessach V, Meltser A, Kamshov A, Ramot Y, Zlotogorski A. STAT1 gain‐of‐function and chronic demodicosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:153–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Second J, Korganow AS, Jannier S, Puel A, Lipsker D. Rosacea and demodicidosis associated with gain‐of‐function mutation in STAT1. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:e542–e544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saez‐de‐Ocariz M, Suarez‐Gutierrez M, Migaud M, O′ Farrill‐Romanillos P, Casanova JL, et al. Rosacea as a striking feature in family members with a STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e265–e267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith TF, Waterman MS. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J Mol Biol. 1981;147:195–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poplin RR‐RV, DePristo MA, Fennell TJ, Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples. bioRxiv 2017. doi: 10.1101/201178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li M, Li J, Li MJ, Pan Z, Hsu JS, Liu DJ, et al. Robust and rapid algorithms facilitate large‐scale whole genome sequencing downstream analysis in an integrative framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, Gascoyne RD, Cassileth PA, Cohn JB, et al. Rituximab‐CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sampaio EP, Hsu AP, Pechacek J, Bax HI, Dias DL, Paulson ML, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) gain‐of‐function mutations and disseminated coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1624–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, Xu Q, Li X, Wang L, Yang L, Chen Z, et al. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of nine patients with STAT1 GOF mutations in China. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40:82–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng J, van de Veerdonk FL , Crossland KL, Smeekens SP, Chan CM, Al Shehri T, et al. Gain‐of‐function STAT1 mutations impair STAT3 activity in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC). Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2834–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puel A, Cypowyj S, Marodi L, Abel L, Picard C, Casanova JL. Inborn errors of human IL‐17 immunity underlie chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:616–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al Shehri T, Gilmour K, Gothe F, Loughlin S, Bibi S, Rowan AD, et al. Novel gain‐of‐function mutation in Stat1 sumoylation site leads to CMC/CID phenotype responsive to ruxolitinib. J Clin Immunol. 2019;39:776–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henrickson SE, Dolan JG, Forbes LR, Vargas‐Hernandez A, Nishimura S, Okada S, et al. Gain‐of‐function STAT1 mutation with familial lymphadenopathy and Hodgkin lymphoma. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JT, Lee SH, Chun YS, Kim JC. Tear cytokines and chemokines in patients with Demodex blepharitis. Cytokine 2011;53:94–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobbe R, Kolster M, Fuchs S, Schulze‐Sturm U, Jenderny J, Kochhan L, et al. Common variable immunodeficiency, impaired neurological development and reduced numbers of T regulatory cells in a 10‐year‐old boy with a STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutation. Gene 2016;586:234–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nemoto K, Kawanami T, Hoshina T, Ishimura M, Yamasaki K, Okada S, et al. Impaired B‐cell differentiation in a patient with STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:557521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Zelm MC , Bosco JJ, Aui PM, De Jong S, Hore‐Lacy F, O'Hehir RE, et al. Impaired STAT3‐dependent upregulation of IL2Ralpha in B cells of a patient with a STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutation. Front Immunol. 2019;10:768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vargas‐Hernandez A, Mace EM, Zimmerman O, Zerbe CS, Freeman AF, Rosenzweig S, et al. Ruxolitinib partially reverses functional natural killer cell deficiency in patients with signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) gain‐of‐function mutations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:2142–55 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mossner R, Diering N, Bader O, Forkel S, Overbeck T, Gross U, et al. Ruxolitinib induces interleukin 17 and ameliorates chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis caused by STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutation. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:951–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinacht KG, Charbonnier LM, Alroqi F, Plant A, Qiao Q, Wu H, et al. Ruxolitinib reverses dysregulated T helper cell responses and controls autoimmunity caused by a novel signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) gain‐of‐function mutation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1629–40 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriya K, Suzuki T, Uchida N, Nakano T, Katayama S, Irie M, et al. Ruxolitinib treatment of a patient with steroid‐dependent severe autoimmunity due to STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutation. Int J Hematol. 2020;112:258–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins E, Al Shehri T, McAleer MA, Conlon N, Feighery C, Lilic D, et al. Use of ruxolitinib to successfully treat chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis caused by gain‐of‐function signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) mutation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:551–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bloomfield M, Kanderova V, Parackova Z, Vrabcova P, Svaton M, Fronkova E, et al. Utility of ruxolitinib in a child with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis caused by a novel STAT1 gain‐of‐function mutation. J Clin Immunol. 2018;38:589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lacey N, Russell‐Hallinan A, Zouboulis CC, Powell FC. Demodex mites modulate sebocyte immune reaction: possible role in the pathogenesis of rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:420–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okada S, Puel A, Casanova JL, Kobayashi M. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis disease associated with inborn errors of IL‐17 immunity. Clin Transl Immunol. 2016;5:e114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carey B, Lambourne J, Porter S, Hodgson T. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis due to gain‐of‐function mutation in STAT1. Oral Dis. 2019;25:684–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedraza‐Sanchez S, Lezana‐Fernandez JL, Gonzalez Y, Martinez‐Robles L, Ventura‐Ayala ML, Sadowinski‐Pine S, et al. Disseminated tuberculosis and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in a patient with a gain‐of‐function mutation in signal transduction and activator of transcription 1. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharfe N, Nahum A, Newell A, Dadi H, Ngan B, Pereira SL, et al. Fatal combined immunodeficiency associated with heterozygous mutation in STAT1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:807–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu L, Okada S, Kong XF, Kreins AY, Cypowyj S, Abhyankar A, et al. Gain‐of‐function human STAT1 mutations impair IL‐17 immunity and underlie chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1635–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia‐Prat M, Alvarez‐Sierra D, Aguilo‐Cucurull A, Salgado‐Perandres S, Briongos‐Sebastian S, Franco‐Jarava C, et al. Extended immunophenotyping reference values in a healthy pediatric population. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2019;96:223–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Apoil PA, Puissant‐Lubrano B, Congy‐Jolivet N, Peres M, Tkaczuk J, Roubinet F, et al. Reference values for T, B and NK human lymphocyte subpopulations in adults. Data Brief. 2017;12:400–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jolliff CR, Cost KM, Stivrins PC, Grossman PP, Nolte CR, Franco SM, et al. Reference intervals for serum IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C4 as determined by rate nephelometry. Clin Chem. 1982;28:126–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martins TB, Bandhauer ME, Bunker AM, Roberts WL, Hill HR. New childhood and adult reference intervals for total IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:589–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the authors.