Abstract

The usefulness of the measurement of urinary lactoferrin (LF) released from polymorphonuclear leukocytes and of an immunochromatography test strip devised for measuring urinary LF for the simple and rapid diagnosis of urinary tract infections (UTI) was evaluated. Urine specimens were collected from apparently healthy persons and patients diagnosed as suffering from UTI. In the preliminary study, the LF concentrations in 121 normal specimens and 88 specimens from patients (60 with UTI) were quantified by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The LF concentration was 3,300.0 ± 646.3 ng/ml (average ± standard error of the mean) in the specimens from UTI patients, whereas it was 30.4 ± 2.7 ng/ml and 60.3 ± 14.9 ng/ml in the specimens from healthy persons and the patients without UTI, respectively. Based on these results, a 200-ng/ml LF concentration was chosen as the cutoff value for negativity. Each urine specimen was reexamined with the newly devised immunochromatography (IC) test strip to calculate the indices of efficacy. Based on the cutoff value, it was calculated that the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the IC test were 93.3, 89.3, 86.2, and 94.9%, respectively, compared with the results of the microscopic examination of the urine specimens for the presence of leukocytes. The respective indices for UTI were calculated as 95.0, 92.9, 89.7, and 96.6%. The tests were completed within 10 min. These results indicated that urine LF measurement with the IC test strip provides a useful tool for the simple and rapid diagnosis of UTI.

Urinary tract infections (UTI) are among the most common diseases of humans, and large numbers of urine specimens are processed daily in most clinical microbiology laboratories. The screening of these specimens for microorganisms is a repetitive procedure with a quantitative distinction between positive and negative results (9, 23). The majority of the test results are negative (11, 14), leaving positive specimens for further processing. Most such tests are relatively simple and reliable but require an overnight incubation of cultures before results are available. Therefore, a rapid screening test would be advantageous if it greatly reduced the time spent on specimens which prove to be negative (thereby allowing the majority of negative reports to be issued the same day that the specimens are received) and required the culture of only positive specimens. The detection of pyuria, in which polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) are present due to inflammation of the UT, may aid in the diagnosis of UTI (1, 16); pyuria accompanied by a low or negligible bacterial count is a significant finding (13, 15, 20, 25, 26). The presence of asymptomatic and bacteriuritic pyuria may indicate infection rather than colonization (10, 17, 27). However, the current methods for detecting pyuria require some experience on the part of the microscopist and can also be time-consuming. A rapid report of results leading to a diagnosis of UTI would be useful to the physician and patients because unnecessary therapy might be avoided.

A test using the esterase activity of PMNs combined with the azo-coupling reaction (5, 19, 24) was reported to simplify the diagnosis of UTI. In addition to esterase, PMNs contain another component, the stable iron-binding protein lactoferrin (LF), in their nuclei and secondary granules (6, 21). The present study was carried out to test the usefulness of the measurement of urinary LF for the diagnosis of UTI and to evaluate the immunochromatography (IC) test strip devised for measuring urinary LF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Urine specimens and UTI criteria.

The first-voided morning urine specimens were obtained from apparently healthy persons (72 men aged 24 to 59 and 49 women aged 20 to 55). Urine specimens of outpatients were also collected from 45 men aged 40 to 83 (catheterized, 20%; midstream, 27%; and unspecified, 53%) and from 43 women aged 2 to 87 (catheterized, 42%; midstream, 2%; and unspecified 56%). The specimens were stored immediately at 4°C and submitted to the clinical laboratory within 2 h.

The calibrated-loop technique for bacterial culture and microscopic examination of uncentrifuged urine specimens were carried out according to the method of Clarridge et al. (2).

The guidelines to establish a test result as UTI positive for the purpose of this study were as follows: (i) for acute cystitis, which is one of the uncomplicated UTIs, female population aged 16 to 69, dysuria, frequency, urgency, and/or suprapubic pain, PMNs at ≧10/mm3, and a bacterial count of ≧103 CFU/ml of at least one clearly predominating organism before antibiotic therapy; (ii) for acute pyelonephritis, which is also one of the uncomplicated UTIs, female population aged 16 to 69, fever of ≧37°C with flank pain, PMNs at ≧10/mm3, and a bacterial count of ≧104 CFU/ml; (iii) for complicated UTI; both male and female populations having at least one underlying disease of the UT, PMNs at ≧10/mm3, and a bacterial count of ≧104 CFU/ml.

Preparation of PMN lysate.

PMNs were collected from normal heparinized venous blood according to the method of Ferrante and Thong (4). The PMNs were suspended in 100 mM borate-buffered saline (BBS), pH 8.2, containing 0.07% Zwittergent 3-14 (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, La Jolla, Calif.), 0.07% CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate} (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan), 0.07% BIGCHAP (Dojindo), 0.2% Triton X-100 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), and 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) (this is hereafter referred to as the “sample dilution buffer”) followed by sonication for 1 min to lyse PMNs and release LF.

Preparation of polyclonal antibody to LF.

Female Japanese white rabbits (5 weeks old; 2.5-kg body weight) were immunized subcutaneously with 2 mg of LF (Sigma) in Freund’s complete adjuvant (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). Two and 4 weeks later, the rabbits were boosted subcutaneously with 0.5 mg of LF in complete adjuvant. One week after the final immunization, whole blood was collected for sera. The antibody was purified from the sera by precipitation at between 20 and 33% saturation with (NH4)2SO4. The antibody was then diluted with 50 mM carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6, for use as the immobilized antibody and was also biotinylated with a protein biotinylation module (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) for use as the second antibody of the sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Preparation of monoclonal antibodies to LF.

Female BALB/cA mice (4 weeks old) were immunized subcutaneously with 100 μg of LF in complete adjuvant. Four and 8 weeks later, the mice were immunized again in the same way. Three days after the final immunization, splenocytes of the mice were mixed with P3-X63-Ag8-6.5.3 myeloma cells at a ratio of 5:1 and fused in polyethylene glycol 1500 (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) by a modification of the method of Koeler and Milstein (12). Positive hybridomas were selected by limiting dilution and further incubated in Celgrosser-H serum-free medium (Sumitomo Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Antibodies were purified from the supernatants of cell cultures by an affinity chromatographic technique with an AvidChrom IgPure Isolation kit (Unisyn Technologies, San Diego, Calif.), which has low-molecular-weight ligands on the surface of Sepharose C1-4B to capture immunoglobulin G (IgG), according to the method of Ngo and Khatter (18).

Among the 14 monoclonal antibodies prepared, 17B04-08 [IgG1(κ)] was used as the antibody immobilized on an Immunodyne ABC membrane (3-μm pore size) (Pall Gelman Sciences, New York, N.Y.), which is made from nylon66 and has a high density of chemically activated covalent binding sites against amino groups, and 32D01-10 [IgG2a(κ)] was used as the antibody conjugated with AuroBeads G10 colloidal gold particles (Amersham) for the sandwich-type IC system.

Sandwich ELISA of LF.

The polyclonal antibody to LF (10 μg/ml) was immobilized in each well of 96-well microtiter plates (catalog no. 3590; Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) overnight at 4°C followed by blocking with 1% gelatin (enzyme immunoassay grade; Bio-Rad) for 1 h at 37°C. After the washing of each well, urine specimens diluted with the sample dilution buffer were allowed to react for 1 h at 37°C. After the wells were washed, biotinylated polyclonal antibody (2 μg/ml) was added and allowed to react for 1 h at 37°C. After another washing, alkaline phosphatase-avidin complex (1:1,000) (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) was added and allowed to react for 30 min at 37°C. After a final washing, p-nitrophenylphosphate solution (1 mg/ml in 9.7% diethanolamine and 0.01% MgCl2 solution, pH 9.8) was added and allowed to react for 10 min. After the reaction was stopped by the addition of 4 M NaOH solution, the absorbance of each well at 405 nm was measured with a microplate reader (EL 312e; Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.).

IC of LF.

All solutions and buffers used to prepare the IC test strip were filtered with 0.22-μm-pore-size membrane filters before use.

17B04-08 antibody (3 mg/ml in BBS) was deposited on an Immunodyne ABC membrane (5 by 35 mm) as a 1-mm-wide line at about the midpoint of the length of the membrane as the detection zone of LF. As the control zone, rabbit anti-mouse Ig (3 mg/ml in BBS) (Dako) was deposited on the membrane as a 1-mm-wide line 5 mm downstream from the detection zone. After drying for 1 h at room temperature and for 10 min at 37°C, the membrane was blocked with 0.5% monoethanolamine in BBS, pH 8.5, for 30 min at room temperature and further with 0.5% Hammarsten’s casein (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in 100 mM maleic acid and 150 mM NaCl solution, pH 7.5, for 30 min at room temperature with continuous agitation. After being rinsed once with BBS and three times with distilled water, the membrane was dried at 37°C.

The 32D01-10 antibody was dialyzed against 2 mM Na2B4O7 buffer, pH 9.0 (borax buffer) at 4°C, followed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 5°C in an ultracentrifuge equipped with a 50Ti rotor (L8-50M/E; Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, Calif.). The supernatant of the solution was collected and further diluted with ultracentrifuged borax buffer. A 1-ml aliquot of 32D01-10 antibody solution (240 μg/ml) was added to a 10-ml aliquot of AuroBeads G10 colloidal gold suspension (pH 9.0) in a glass tube. The mixture was then stirred continuously for 2 min and stored for 10 min at room temperature. After the addition of a 1.5-ml aliquot of 10% BSA solution, pH 9.0, the antibody-gold conjugate was washed with 20 mM Tris-HCl–150 mM NaCl buffer containing 1% BSA, pH 8.0, in a series of three centrifugation steps at 45,000 × g at 5°C for 30 min. The final pellet was resuspended in the same buffer, and the absorbance of the suspension at 520 nm was adjusted to 10. A 2-μl aliquot of the antibody-gold conjugate suspension was deposited on the glass fiber absorbent pad (5 by 34 mm) at the downstream end and allowed to dry at room temperature.

A polystyrene support (5 by 80 mm) was laminated on the back of the antibody-immobilized membrane, and the antibody-gold conjugate pad was attached to the support at the upstream end with 2 mm overlapping with the membrane. Then another absorbent pad made from cellulose (5 by 20 mm) was incorporated with the downstream end of the support, with 7 mm overlapping with the membrane, to serve as a sink for any excess volume of liquid sample.

A 100-μl aliquot of each urine specimen diluted 1:4 with the sample dilution buffer and the PMN lysate was deposited on the upstream end of the antibody-gold conjugate pad. After a 10-min migration of the antibody-gold conjugate with LF through the membrane at room temperature, the lines at both the detection zone and the control zone caused by the capture of the antibody-gold conjugate were evaluated by the naked eye.

Data analysis.

The data from the microplate reader were processed on a Macintosh computer, and a reduction was performed with DELTA SOFT II (BioMetallics, Princeton, N.J.). The reduction was a four-parameter algorithm with the absorbance at 405 nm on the y-axis and the LF concentration (in namograms per milliliter) on the x-axis.

Statistical analysis.

The quantitative detection range of LF by a sandwich ELISA and the significance of the difference between each pair of mean values of urinary LF were analyzed by using Student’s t test, where the standard error of the mean (SEM) was used as a measure of variance among the means.

Indices of efficacy.

The indices of efficacy of the IC test of LF in comparison with the results of urinary PMNs and those for predicting UTI were calculated based on the methods described by Ranshoff and Feinstein (22).

RESULTS

Polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies to LF.

The polyclonal antibody and 14 monoclonal antibodies to LF did not cross-react with transferrin or bovine LF when examined by an ELISA method with these antigens immobilized in the wells of microtiter plates. Moreover, the two monoclonal antibodies, 17B04-08 and 32D01-10, used for the IC test strip were shown to have specificities for different epitopes on the LF molecule when examined by a sandwich ELISA.

Sandwich ELISA of LF.

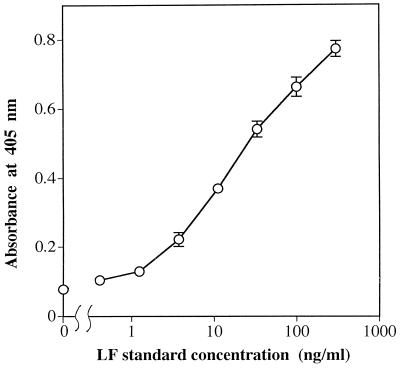

To quantitatively assess the detectable range of LF, standard solutions of LF at concentrations from 411.5 pg/ml to 300 ng/ml were examined. As shown in Fig. 1, a well-fitted standard curve was obtained (n = 6; r = 0.998; P < 0.001). The quantitative detection range of LF was from 4.8 to 117 ng/ml (n = 6; P < 0.001).

FIG. 1.

Sigmoidal standard curve for LF measured by a sandwich ELISA. A 100-μl aliquot of each LF standard solution at concentrations from 411.5 pg/ml to 300 ng/ml was examined. Each value represents the mean (open circle) and SD (error bar) of six independent analyses.

Normal urine specimens fortified with various amounts of LF (0, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 300 ng of LF/ml of urine) were diluted 1:5 and examined to evaluate the LF recovery rates throughout the procedure. As summarized in Table 1, the mean recovery rates obtained with each level of added LF ranged from 88.4 to 124.8%, with standard deviations (SD) of from 5.0 to 26.4%.

TABLE 1.

Recovery of LF added to normal urine specimens

| Amount of LFa added (ng/ml of urine) | Amount of LF found (ng/ml of urine)b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Urine A | Urine B | Urine C | |

| 0 | 6.2 ± 6.7 | 7.5 ± 1.4 | 22.7 ± 3.5 |

| 25 | 36.6 ± 6.7 (121.6) | 36.7 ± 4.1 (116.8) | 44.8 ± 5.8 (88.4) |

| 50 | 59.0 ± 14.0 (105.6) | 69.9 ± 2.8 (124.8) | 71.5 ± 7.5 (97.6) |

| 100 | 108.9 ± 9.1 (102.7) | 113.5 ± 14.7 (106.0) | 132.0 ± 19.2 (109.3) |

| 200 | 192.9 ± 32.5 (93.3) | 221.6 ± 17.4 (107.1) | 230.7 ± 33.3 (104.0) |

| 300 | 303.6 ± 31.6 (99.1) | 280.4 ± 47.8 (91.0) | 310.5 ± 44.4 (95.9) |

A 1-ml aliquot of each LF solution was added to a 1-ml aliquot of each normal urine specimen and the mixture was diluted to a final volume of 5 ml with the sample dilution buffer.

Each value is the mean ± SD for six independent analyses. The figures in parentheses show recovery rates (%).

We examined 121 urine specimens from apparently healthy persons, 28 from patients without UTI, and 60 from UTI patients (33 with uncomplicated UTI and 27 with complicated UTI). The results are summarized in Table 2 as the mean (±SEM) urinary LF concentration. No significant difference in LF concentration was observed between the uncomplicated and complicated UTI populations. Therefore, the populations were combined as the UTI-positive population for the purpose of this study. We compared the LF concentrations in specimens from the healthy population with those from UTI-negative and UTI-positive populations. There was no significant difference between the healthy and UTI-negative populations, whereas the difference between the UTI-negative and UTI-positive populations was significant (P < 0.001). The urinary LF concentration of the UTI-positive population was more than 50-fold higher than that of the UTI-negative population. These results suggest that an excessive amount of LF was released from PMNs into the urine by inflammatory processes and that urinary LF is a sensitive marker for diagnosis of UTI.

TABLE 2.

Urinary excretion of LF in healthy subjects and patients with and without UTI

| Study population | n | LF conca (ng/ml of urine) |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy | 121 | 30.4 ± 2.7 |

| UTI negative | 28 | 60.3 ± 14.9 |

| UTI positive | 60 | 3,300.0 ± 646.3 |

| Uncomplicated UTI | 33 | 3,907.0 ± 1,062.0 |

| Complicated UTI | 27 | 2,558.2 ± 609.3 |

LF concentration in a urine specimen was determined by a sandwich ELISA with rabbit polyclonal antibody to LF. Each value is the mean ± SEM. Probability of significance of difference: healthy and UTI negative, not significant; uncomplicated and complicated UTI, not significant; UTI negative and UTI positive, P < 0.001.

IC of LF.

To determine the minimum detectable concentration of LF, various amounts of standard LF (0, 20, 50, 100, and 200 ng and 100 μg of LF/ml) were examined. The line produced by capturing the antibody-gold conjugate was observed at the control zone of all test strips, suggesting that the antibody-gold conjugate migrated by capillary action through the membrane beyond the detection zone without aggregation. Another line was revealed on the detection zone by the production of the sandwich immunocomplex of LF and two monoclonal antibodies when the concentration of LF was ≧50 ng/ml. In addition, the detectable concentration range extended to >100 μg/ml without false-negative results due to the prozone phenomenon. These results indicated that this IC system for the detection of LF has a minimum detectable concentration of 50 ng of LF/ml and a wide dynamic range.

The PMN lysate was examined with the IC test strip to detect LF released from PMNs. The results showed that LF in the lysate obtained from ≧104 PMNs/ml could be detected.

Each normal urine specimen containing <20 ng of LF/ml of urine fortified with various amounts of LF (0, 100, 200, 400, and 800 ng of LF/ml of urine) was diluted 1:4 and examined. The results showed that the detectable concentration of LF in the urine was 200 ng of LF/ml of urine.

The LF of each urine specimen quantified by ELISA was reexamined with the IC test strip. The results are summarized in Table 3 as a comparison of the presence of urinary LF with the results of microscopic examination of urinary PMNs and with the UTI diagnosis status. All 121 normal specimens were negative for LF, and 25 of the 28 PMN-negative specimens and 26 of the 28 UTI-negative specimens were assessed as negative based on the IC test strip results. Fifty-six of the 60 PMN-positive specimens and 57 of the 60 UTI-positive specimens were assessed as positive. The sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of negative and positive findings of urinary LF in comparison with the results of urinary PMNs were 93.3, 89.3, 86.2, and 94.9%, and the values for predicting UTI were 95.0, 92.9, 89.7, and 96.6%, respectively. Thus, all indices of efficacy were very high, and the urinary LF examination results reflect the presence of urinary PMNs and predict UTI.

TABLE 3.

Urinary LF compared with urinary PMNs and UTI diagnosis.

| Urinary LFa | Urinary PMNsb

|

UTI diagnosisc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |

| Positive | 56 | 3 | 57 | 2 |

| Negative | 4 | 25 | 3 | 26 |

Each urine specimen was diluted 1:4 with sample dilution buffer and analyzed by IC. Positive urinary LF results are defined as those with ≧200 ng of LF/ml of urine.

Positive PMN results are defined as ≧10/mm3.

Positive UTI results are defined in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we determined the feasibility of using urinary LF as a marker for UTI diagnosis and we evaluated the utility of a simple and rapid test for LF by IC. Because urine specimens contain many substances which interfere with the determination of LF, the analysis of LF in urine specimens has to be carried out in a detergent-rich sample dilution buffer, even though 0.1% Triton X-100 detergent solution alone can release LF from PMNs within 1 min (7).

In the preliminary study, the LF concentration in urine specimens was quantified. For this purpose, we developed a sandwich ELISA with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to LF. The quantitative detection range of LF was from 4.8 to 117 ng/ml. Hetherington et al. reported that 106 PMNs contain about 4.9 μg of LF (8). Therefore, this range requires about 5 × 103 to 1.2 × 105 PMNs/ml of urine and is sufficient to quantify LF in normal urine specimens. In UTI conditions, in which an excessive amount of LF is excreted from PMNs, the volume of the urine specimen to be analyzed can be reduced. The results of the recovery test for LF in normal urine specimens (recovery rates, 88.4 to 124.8%) indicate that the sandwich ELISA method is precise and accurate.

Furthermore, LF in the PMN lysate obtained from ≧104 PMNs/ml could be detected by the IC test strip. This PMN density corresponds to about 50 ng of LF/ml, and the results correlated well with the minimum detectable concentration of LF evaluated with the LF standard solutions. These findings indicate that the IC test strip can detect LF released from PMNs precisely.

For the diagnosis of UTI with LF as a marker, it is important to define the cutoff value of the urinary LF concentration for the separation of negative and positive results. To define the cutoff value, we calculated the mean + 5SD (SEM × √n) value using the results obtained from the healthy population measured by the sandwich ELISA. Although this value was calculated as 180.4 ng of LF/ml of urine, it is difficult to detect a difference of 20 ng of LF/ml of urine with the IC test strip after urine specimens are diluted before examination. Therefore, the cutoff value was defined as 200 ng of LF/ml of urine instead of 180 ng of LF/ml to minimize false-positive results. Based on this cutoff value and the minimum detectable LF concentration of the IC test strip, urine specimens should be diluted 1:4 with the sample dilution buffer before analysis. The LF concentration in the urine detectable by the IC test strip is well correlated with the minimum detectable concentration determined with standard LF and the cutoff value determined according to the results of the ELISA. This indicates that urinary LF can be detected precisely by the IC test strip without serious interference by other substances present in urine.

The LF concentrations in urine specimens from UTI patients were much higher than those in specimens from both patients without UTI and healthy subjects. When the cutoff value for detecting the presence of urinary LF was set at 200 ng of LF/ml of urine, the LF positivity and negativity correlated well not only with the microscopic examination results of PMNs but also with UTI diagnosis. Furthermore, LF is stable in urine specimens even after the structures of PMNs are destroyed. For example, our preliminary experiments showed that the residual rates of LF from a normal urine specimen which was fortified with 200 ng of LF/ml of urine were 113.8% after storage at 45°C for 3 days and 94.4% after three cycles of freezing and thawing. Therefore, it is not always necessary to specify the time of specimen collection and the storage temperature. In addition, interfering reactions caused by reducing agents or antibiotics, as observed in the leukocyte esterase activity test (19), are not a problem, because this detection system for LF is based on a specific antibody-antigen reaction. Indeed, all nine of the urine specimens which were collected after antibiotic medication and which were positive in the microscopic examination of PMNs were positive for LF. Therefore, it is possible to diagnose an inflammation on mucosal surfaces of the UT even after antibiotic medication. Cohen et al. (3) noted that the amount of LF in vaginal mucus ranged from 3.8 to 218 μg/mg of protein. This suggests that it is necessary to use care in the collection of specimens from female patients to avoid false-positive results caused by contamination of LF by vaginal secretions. In the present study, however, no false-positive result was observed in any of the urine specimens from females examined. However, the LF results of all six urine specimens from outpatients for whom the method of specimen collection was not specified were negative, although their bacterial culture results were all positive. These results should be considered as contamination by bacteria in urine specimens rather than false-negative results of LF, because all six specimens were also negative in the microscopic examination of PMNs.

For the detection of LF, several methods, such as an ELISA (8) and a latex agglutination assay (7), have already been developed. Even though the ELISA can detect 3 ng of LF/ml quantitatively, this method is not recommended for the rapid diagnosis of UTI due to its complicated and time-consuming procedure. In the latex agglutination assay, the minimum detectable concentration of LF is 310 ng/ml. Therefore, it is impossible to detect the cutoff line of 200 ng of LF/ml of urine even if the urine specimen is examined directly without further dilution. The IC test strip has a minimum detectable concentration of 50 ng of LF/ml and is able to detect the cutoff line even after fourfold dilution of a urine specimen. In addition, all examination processes can be completed within 10 min after specimen collection.

In conclusion, urinary LF is a sensitive marker for the diagnosis of UTI caused by inflammatory pathogens. The IC test strip provides a useful tool for the simple and rapid diagnosis of UTI. Large numbers of urine specimens are processed daily for the overnight bacterial culture test to determine the inflammatory pathogens, even though the majority of test results are negative. And the microscopic examination of PMNs requires skill and experience on the part of the microscopist. Therefore, the use of the IC test strip to detect LF could greatly reduce the time, cost, and effort of routine urinalysis and could avoid unnecessary antibiotic medication of UTI-negative patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are greatly indebted to R. Sakazaki of the Nippon Institute of Biological Sciences and K. Tamura of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases for their valuable suggestions. We also thank Y. Ohkubo and H. Matsuoka of Wakunaga Pharmaceutical Co. for their technical support in the use of the immunochromatography system.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brumfitt W. Urinary cell counts and their value. J Clin Pathol. 1965;18:550–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarridge J E, Pezzlo M T, Vosti K L. Cumitech 2A. 1987. Laboratory diagnosis of urinary tract infections. Coordinating ed., A. S. Weissfeld. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen M S, Britigan B E, French M, Bean K. Preliminary observations on lactoferrin secretion in human vaginal mucus: variations during the menstrual cycle, evidence of hormonal regulation and implications for infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1122–1125. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrante A, Thong Y H. Optimal conditions for simultaneous purification of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocytes from human blood by the Hypaque-Ficoll method. J Immunol Methods. 1980;36:109–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillenwater J Y. Detection of urinary leukocytes by Chemstrip-L. J Urol. 1981;125:383–384. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green I, Kirkpatrick C H, Dale D C. Lactoferrin-specific localization in the nuclei of human polymorphonuclear neutrophilic leukocytes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1971;137:1311–1317. doi: 10.3181/00379727-137-35779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerrant R L, Araujo V, Soares E, Kotroff K, Lima A A M, Cooper W H, Lee A G. Measurement of fecal lactoferrin as a marker of fecal leukocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1238–1242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1238-1242.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hetherington S V, Spitznagel J K, Quie P G. An enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) for measurement of lactoferrin. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:183–190. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90314-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoeprich P D. Culture of the urine. J Lab Clin Med. 1960;56:899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kass E H. Asymptomatic infections of the urinary tract. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1956;69:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kass E H. Pyelonephritis and bacteriuria. Ann Intern Med. 1962;56:46–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-56-1-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koeler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;258:495–497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komaroff A L, Friedland G. The dysuria-pyuria syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:452–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198008213030808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunin C M, Zacha E, Paquin A J. Urinary tract infections in schoolchildren. I. Prevalence of bacteriuria and associated urologic findings. N Engl J Med. 1962;266:1287–1296. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196206212662501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little P J, Peddie B A, Sincock A R. Significance of bacterial and white cell counts in midstream urines. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33:58–60. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGeachie J, Kennedy A C. Simplified quantitative methods for bacteriuria and pyuria. J Clin Pathol. 1963;16:32–38. doi: 10.1136/jcp.16.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musher, D. M., S. B. Thorstein, and V. M. Airola. 1976. Quantitative urinalysis. Diagnosing urinary tract infection in men. 236:2069–2072. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ngo T T, Khatter N. Chemistry and preparation of affinity ligands useful in immunoglobulin isolation and serum protein separation. J Chromatogr. 1990;510:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)93762-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oneson R, Gröschel D H M. Leukocyte esterase activity and nitrite test as a rapid screen for significant bacteriuria. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:84–87. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/83.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pryles C V. The diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Pediatrics. 1960;26:441–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pryzwansky K B, Martin L E, Spitznagel J K. Immunocytochemical localization of myeloperoxidase, lactoferrin, lysozyme and natural proteases in human monocytes and neutrophilic granulocytes. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1978;24:295–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranshoff D F, Feinstein A R. Problems of spectrum and bias in evaluating the efficacy of diagnostic tests. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:926–930. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197810262991705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savage W E, Hajj S N, Kass E H. Demographic and prognostic characteristics of bacteriuria in pregnancy. Medicine. 1967;46:385–407. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196709000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smalley D L, Dittmann A N. Use of leukocyte esterase-nitrate activity as predictive assays of significant bacteriuria. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:1256–1257. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.5.1256-1257.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamm W E, Counts G W, Running K R, Fihn S, Turck M, Holmes K K. Diagnosis of coliform infection in acutely dysuric women. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:463–468. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208193070802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stamm W E, Wagner K F, Amsel R, Alexander E R, Turck M, Counts G W, Holmes K K. Causes of the acute urethral syndrome in women. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:409–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198008213030801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams J D, Leigh D A, Rosser E, Brumfitt W. The organization and results of a screening program for the detection of bacteriuria of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1965;72:327–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1965.tb01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]