Abstract

Gamma-butyrolactone (GBL), a commonly used industrial solvent, is used recreationally as a central nervous system (CNS) depressant and, therefore, is a United States Drug Enforcement Agency List 1 chemical of the Controlled Substances Act. GBL was identified presumptively in the liquid from JUUL Virginia Tobacco flavored pods during routine untargeted screening analysis of e-cigarette products by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Methods for the analysis of GBL were developed for GC–MS and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS-MS) in the liquids and the aerosol generated from the liquid. Three flavors of JUUL pods available at the time of analysis were obtained by direct purchase from the manufacturer, purchase from a local vape shop and submission from a third party. The only liquid flavor to contain GBL was Virginia Tobacco, with an average of 0.37 mg/mL of GBL, and it was detected in the aerosol. Studies evaluating the pharmacological effects of inhaling GBL do not exist; however, a case report of chronic oral GBL ingestion indicates acute lung injury. The identification of GBL in an e-cigarette product purportedly compliant with federal regulation continues to demonstrate public health and public safety concerns.

Introduction

Gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) is a small, lipophilic molecule that readily absorbs in the body when consumed orally. In vitro, GBL and gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) are subject to interconversion depending on the pH (1). In vivo, GBL is a precursor to GHB, an endogenous chemical that is found in low concentrations in the body. GBL is rapidly metabolized to GHB by the enzyme lactonase, found in the blood and liver, with a mechanism of action similar to the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmitter (2–4). Evidence also suggests that it affects the balance of neurotransmitters of the GABA, cholinergic, dopaminergic and serotonergic systems (5). GHB increases the secretion of growth hormones and also causes changes in dopamine levels, affecting neurosteroids and possibly endogenous opioids (5). Some evidence exists of a G-protein coupled GHB-receptor (6). These proposed mechanisms suggest that administration of exogenous GBL/GHB has a widespread effect on various brain regions. When taken chronically, GBL can produce physical dependence and serious withdrawal symptoms (2–4, 7). Symptoms of dependence have been reported as occurring within a few weeks of initial use, and post-withdrawal symptoms have been reported as lasting sometimes months after cessation (4).

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of the oral administration of GHB and GBL have been investigated (4, 5). The effects of GBL are produced by its rapid conversion to GHB, rather than from GBL itself. Because GBL is more lipophilic and absorbs more readily throughout the body than GHB, it has a faster onset. GBL is thought to have a higher abuse potential than GHB because GBL has a greater potency, faster onset of action and longer activity; 1 mL of pure GBL is reported as equivalent to ∼1.6–2.5 g of GHB (2–4, 7). The pharmacological effects of GHB last 1–4 hours, with complete elimination from urine typically occurring within 12 hours (5). Inhalation of GHB and GBL has not been investigated in humans, and little data for occupational exposure data exist. A respirator is indicated for safe handling (8), and a single case report describes significant acute lung injury (ALI) from a combination of ingestion and inhalation after self-dosing 2 mL of GBL every 2 hours orally for 3 months (9).

Oral dosages of GBL are generally in the single milliliter range (2, 3, 5, 7). Use of GBL, especially with alcohol and narcotics, has been linked to several serious side effects, including mental changes, respiratory depression, loss of consciousness, coma and death (3, 7, 10). With repeated use, symptoms of dependence can develop within days to a few weeks; physical dependence has been reported along with severe withdrawal symptoms that are similar to alcohol, heroin and other sedative-hypnotic drugs and can last more than 14 days (2–4, 7). Commonly reported symptoms of withdrawal are tremors, hallucinations, anxiety, delirium, seizures and insomnia (4). Post-withdrawal symptoms have also been reported, including depression, panic attacks, insomnia and withdrawal from social interactions, with a time course lasting from several weeks to months (4).

Epidemiology of GBL use is difficult to discern since it is linked to GHB, and neither chemical is part of routine drug screens. Reports generally agree that most users are in their teens to mid-30s, male and often identify as gay (2, 4). United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services collects data on GBL/GHB independently but reports them together (10), and the 2012 National Survey describes consistent recreational use (11). A survey to club patrons in South London identified trends of GBL/GHB use in vaping devices as early as March of 2015 (12). GBL is often associated with poly-substance use. The most common reported drugs taken with GBL/GHB are alcohol (as a means of delivery), other “club drugs”, amphetamines and narcotics (3, 7, 13). Taking GBL in conjunction with other pharmacologically active chemicals can lead to serious side effects due to potentiation and drug–drug interactions.

GBL is a colorless oily liquid associated with several Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemical (GHS) classes due to its corrosive, acute toxic and irritant properties. It is used in a wide variety of industries as a common solvent, cleaning agent, cosmetic ingredient and as an aromatic, as well as in the manufacturing of pyrrolidones, polymers, herbicides and some pharmaceuticals (1, 7, 10, 14, 15). GBL is registered by the Flavor Extract Manufacturers Association and the European Union for use as a flavoring substance and has been reported as natural constituents in foodstuffs such as wine, coffee, tropical fruits, teas and various beans (1, 16–18). It is described as having a flavor profile from bitter, stale, water to buttery, caramel, cheesy or nutty taste with a faint pleasant to burnt plastic odor (2, 7, 16, 18). A joint Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations-World Health Organization Expert Committee Report on Food Additives from 2000 reported there was “no safety concern at current levels of intake when used as a flavouring agent” (19). GHB is designated as unsafe by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and banned from sale for human consumption (15). Since GHB is a controlled substance in many countries due to its potential for misuse and recreational use, GBL and 1,4-butanediol have been adopted as pro-drug alternatives (2). GBL is not as widely or stringently regulated due to its extensive legitimate industrial uses, leading to its wide availability (1, 2, 7). The United Kingdom, Canada and many other countries have regulated GBL under national laws (7).

The United States classified GBL as a List I chemical in the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Drug Prohibition Act of 2000. In 2010 the United States Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) finalized a proposed rule that would allow them to regulate chemical mixtures greater than 70% GBL as they are considered to be a high risk for diversion, while mixtures 70% or less would be exempt from such regulation (10). A List 1 chemical is designated as having legitimate uses but is also important to the manufacture of a controlled substance in violation of the Controlled Substances Act (20).

The following report documents the identification of GBL in commercially available JUUL brand electronic cigarette (e-cigarette; i.e., electronic nicotine delivery system) liquid formulations, manufactured by JUUL Labs, Inc. E-cigarette liquids were screened using an untargeted screening method by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Identification of GBL was confirmed using primary reference material. A liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS-MS) method was used to quantitate GBL in both the e-cigarette liquid and corresponding aerosol.

Materials

Five JUUL “Virginia Tobacco” flavored liquid pods (lot HK09GA01A, JUUL Labs, Inc.) (Figure 1) were submitted to the lab for characterization. Nine JUUL products encompassing all available flavors (Classic Tobacco, Virginia Tobacco and Menthol) were also purchased directly from the manufacturer or from local retailers (Table I) to acquire products with different lot numbers. All products were purchased in the United States.

Figure 1.

Packaging from original JUUL product submitted for product characterization.

Table I.

JUUL Products Evaluated

| Product | Lot | Date purchased | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| VA Tobacco 5% | HK09GA01A | Late 2019 | Online and submitted to lab |

| Classic Tobacco 5% | HMO3NA18A | 7/6/2020 | JUUL website |

| Classic Tobacco 3% | HK04NA17B | 7/6/2020 | JUUL website |

| VA Tobacco 5% | JF12SA20A | 7/6/2020 | JUUL website |

| VA Tobacco 3% | JF07NA16B | 7/6/2020 | JUUL website |

| Menthol 5% | JE28CA08A | 7/6/2020 | JUUL website |

| Menthol 3% | JF17NA17B | 7/6/2020 | JUUL website |

| Classic Tobacco 3% | HG22PA09B | 8/2/2020 | Local vendor |

| VA Tobacco 5% | GJ05GD04A | 8/2/2020 | Local vendor |

| Menthol 3% | HG23PA06B | 8/2/2020 | Local vendor |

All glassware, tubing and fritted glass dispersion tubes were purchased from Colonial Scientific (Richmond, VA, USA). United States Pharmacopeia grade propylene glycol (PG) and vegetable glycerin (VG) were purchased from Wizard Labs (Altamonte Springs, FL, USA). HPLC grade acetone and Optima grade formic acid, isopropanol and methanol were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL, USA). Ethanol (200 proof) was purchased from Decon Labs (King of Prussia, PA, USA). T-Butanol was purchased from Honeywell Riedel-de Haën (Seelze, Germany). Air, helium and hydrogen gases were purchased from Praxair (Richmond, VA, USA). Type 1 water was generated in-house using a Millipore Direct-Q3 system. A GHB reference standard was purchased from Cerilliant (Round Rock, TX, USA). GBL and 1,4-butanediol reference standards were purchased from Restek (Bellefonte, PA, USA). GBL-d6 reference standard was purchased from IsoSciences (Ambler, PA, USA). (-)-Nicotine (≥99% (GC)), quinoline (reagent grade, 98%), caffeine and menthol were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Reference materials for a quality assurance test mix containing amitriptyline, diazepam, fluoxetine, methadone, nicotine, nordiazepam, norfluoxetine, nortriptyline, paroxetine and trazodone were acquired from Cerilliant (Round Rock, TX, USA).

Methods

Screening by GC–MS

e-Cigarette liquids were screened by making a 1:100 dilution in methanol and analyzing using an untargeted GC–MS base screen method. An untargeted analytical method is preferable to a targeted method when working with highly variable products such as e-cigarette liquids. Screening was performed on a Shimadzu QP-2020 GC–MS (Kyoto, Japan) controlled by GCMS Real Time Analysis version 4 (Shimadzu Corp. Kyoto, Japan). The chromatographic separation was performed on a HP-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm id × 0.25 μm) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The GC–MS was operated in the splitless mode using 1 μL sample injections. The carrier gas was helium at a linear velocity of 35 cm/s. The oven temperature was programed to hold for 1 min at 70°C and, then, ramped at 15°C per min to 300°C and held for 10 min for a total run time of 26.33 min. The scan range for the mass spectrometer was m/z 40–550 . A test mix containing 10 compounds was injected prior to the samples. Correct retention time, peak shape and abundance were evaluated to ensure the instrument was operating optimally. Methanol blanks were injected between samples to check for contamination and/or carryover. National Institute of Standards and Technology and Scientific Working Group for the Analysis of Seized Drugs libraries were used for identification. Upon identification of GBL in the JUUL Virginia Tobacco liquids, a GBL reference standard was injected to confirm retention time and spectra.

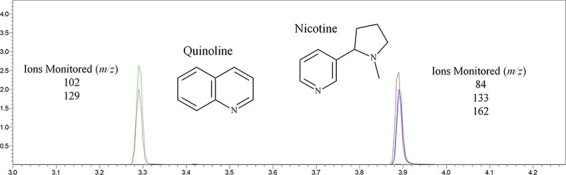

Quantitation of nicotine by GC–MS

Calibrators were prepared at 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 µg/mL nicotine in methanol. The limit of quantitation was 10 μg/mL with a linear range of 10–500 µg/mL. Lots of matrix matched quality controls (QCs) were prepared at 30, 150 and 300 µg/mL nicotine. e-Cigarette liquids were diluted 1:100 in methanol by adding 5 µL of a 30:70 PG:VG mixture as part of the total 100 µL volume. Calibrators, controls in triplicate, blank matrix with and without internal standard and samples were prepared for analysis by adding 100 µL to a vial with a glass insert with 15 µL internal standard (2,000 µg/mL quinoline in methanol). Quantitation of nicotine was accomplished by GC–MS using a Shimadzu QP-2020 GC–MS (Kyoto, Japan) controlled by GCMS Real Time Analysis version 4 (Shimadzu Corp. Kyoto, Japan) following previously published parameters (21). The chromatographic separation was performed on an HP-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm id × 0.25 μm) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Helium carrier gas was run through a split injector (50:1 split) at a temperature of 230°C. The injection volume was 1 µL of sample. The initial oven temperature was 80°C held for 1 min and then ramped at 25°C per min to 245°C and held for 4.5 min for a total run time of 11.10 min. The source and transfer line were kept at 180 and 280°C, respectively. Single-ion-monitoring (SIM) mode was used, monitoring m/z values of 84 (quantitation), 133 and 162 for nicotine and 129 (quantitation) and 102 for quinolone. Methanol blanks were evaluated for contamination and carryover. Imprecision, accuracy and measurement of uncertainty were determined by evaluating low (30 µg/mL), mid (150 µg/mL) and high (300 μg/mL) QC concentrations. Each was repeated three times on three different days for intraday precision. Accuracy was calculated as the percent of the target concentration and imprecision was calculated as the percent coefficient of variation (%CV). Accuracy was within 15% and %CV was within 15%. Instrument repeatability was calculated by injecting each QC three times and calculating the mean and standard deviation. Bias was calculated as the percent difference between the calculated values and actual values and was within ±15%. Carryover was assessed by injecting a double blank after the highest calibrator and between QC samples and product samples. Carryover was not detected.

Quantitation of volatiles by HS-GC-FID

e-Cigarette liquids were diluted 1:10 in deionized (DI) water. Calibrators were prepared at 100, 300, 500, 900, 1,500 and 3,000 µg/mL of acetone, ethanol, isopropanol, and methanol in water. Lots of matrix matched QCs were prepared at 200, 600 and 2,000 µg/mL acetone, ethanol, isopropanol and methanol in 30:70 PG:VG mixture. e-Cigarette liquid samples were diluted 1:10 in DI water. Calibrators, controls in triplicate, blank matrix with and without internal standard and samples were prepared for analysis by adding 100 µL to a headspace vial with 1 mL internal standard (20 mg/L t-butanol in water). The limit of detection (LOD) for all volatiles was 100 mg/L with a linear range of 100–3,000 mg/L. Analysis of acetone, ethanol, isopropanol and methanol was accomplished using a modified previously published method (22). In brief, a Shimadzu HS-20 headspace sampler attached to a Nexis 2030 GC-dual FID controlled by LabSolutions software (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) was employed. The chromatographic separation was performed on RTX-BAC PLUS 1 (30 m× 0.32 mm id × 1.80 µm) and RTX-BAC PLUS 2 (30 m× 0.32 mm id × 0.6 µm) columns (Restek Corp, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The sample line and transfer line temperatures were set to 170°C, and the platen temperature was 80°C with the mixer on. The incubation time was 5 min with a sample injection time of 0.5 min. The GC oven temperature was set to 40°C with an injection temperature of 200°C run in a split mode with a 1:20 ratio. The column flow rate was 2.57 mL/min with purge flow of 0.5 mL/min, and the detector temperature was 225°C. Accuracy was within 15% and %CV was within 15%. Instrument repeatability was calculated by injecting each QC three times and calculating the mean and standard deviation. Bias was calculated as the percent difference between the calculated values and actual values and was within ±15%. Carryover was assessed by injecting a double blank after the highest calibrator and between QC samples and product samples. Carryover was not detected.

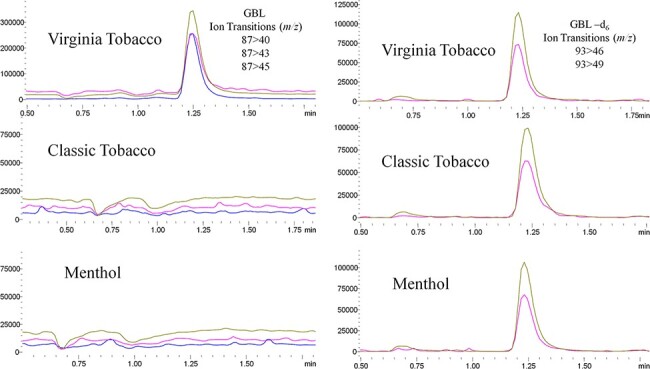

Quantitation of GBL by LC–MS-MS

With each analysis, matrix matched calibrators were prepared at 100, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000 and 5,000 ng/mL GBL in water with 10 µL of a 30:70 PG:VG mixture for a total volume of 1 mL. Matrix matched controls were prepared at 300, 800 and 4,000 ng/mL GBL in 30:70 PG:VG mixture. e-Cigarette liquids were diluted 1:100 with diluent (10% methanol in DI water). To determine if GBL was present in the aerosol, a previously published aerosol water trap method was used (23). In brief, the aerosol trap consisted of tubing placed snugly over the mouthpiece of the pod and connected to two filtering flasks that were connected in tandem followed by a flow meter. Glass wool was packed between the two traps as a filter. DI water (100 mL) was placed in the reservoir of each trap, and a gas dispersion tube bubbled the aerosol through the system at a flow rate of 2.3 L/min. The trap was started before the e-cigarette was activated and was used to aerosolize the e-cigarette liquid for 20 4 second “puffs”. The e-cigarette pod was weighed prior to sampling and after the final “puff”. A 1 mL aliquot of the water in the aerosol trap flask was collected. Calibrators, controls in triplicate, blank matrix with and without internal standard and samples were prepared for analysis by adding 1 mL of solution to a vial with 10 µL internal standard (100 µg/mL GBL-d6). The LOD was set at 100 ng/mL with a linear range of 100–5,000 ng/mL. To evaluate for interferences, three sets of calibrators were prepared. One was diluted solely with the diluent, one was prepared with 10 µL of a 70:30 PG:VG blend and brought to volume with diluent and one was prepared with 10 µL of a 70:30 PG:VG blend plus 10 µL of 1,4-butanediol and then brought to volume with diluent.

Quantitation of GBL was accomplished by LC–MS-MS using a Shimadzu LC-MS 8050 controlled with LabSolutions software (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). The method was a modified version of a previously published method (24). Chromatographic separation was performed on an InfinityLab Poroshell 120 SB-AQ column (2.1 × 150 mm id × 2.7 µm) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) held at 40°C. Formic acid 0.1% in water (A) and methanol (B) was used as the mobile phase. A binary gradient was used with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min and the following programming: 0.00–1.00 min: 5% B; 1.01–3.00 min: 85% B; 3.01–5.00 min: 5% B. The source temperature was set at 650°C and had a curtain gas flow rate of 30 mL/min. The ion spray voltage was 5,000 V, with the ion source gases 1 and 2 at flow rates of 60 mL/min. The method was optimized by directly injecting analytes into the electrospray ionization source in a positive mode. The following transition ions (m/z) were monitored in a multiple reaction monitoring mode (lens 1 voltage, collision energy, lens 3 voltage): GBL, 87.0 > 45.0 (−20.0, −14.0, −16.0), 87.0 > 43.0 (−20.0, −14.0, −16.0) and 87.0 > 40.5 (−20.0, −23.0, −17.0); GBL-d6, 93.1 > 49.0 (−18.0, −16.2, −19.0) and 93.1 > 46.0 (−22.0, −17.0, −15.0).

Linearity was confirmed by generating three calibration curves from 100 to 5,000 ng/mL on three different days. The slope was plotted using LabSolutions quantitation software and confirmed by external calculations. Imprecision, accuracy and measurement of uncertainty were determined by evaluating low (300 ng/mL), mid (800 ng/mL) and high (4,000 ng/mL) QC concentrations. Each was repeated three times on three different days for intraday precision. Accuracy was calculated as the percent of the target concentration and imprecision was calculated as the %CV. Accuracy was within 11% and %CV was within 11%. Instrument repeatability was calculated by injecting each QC three times and calculating the mean and standard deviation. Bias was calculated as the percent difference between the calculated values and actual values and was within ±11%. Carryover was assessed by injecting a double blank after the highest calibrator and between QC samples and product samples. Carryover was not detected. Interference was assessed by adding 1,4-butanediol to a fourth set of matrix matched calibrators and QCs; no interferences were detected.

Results

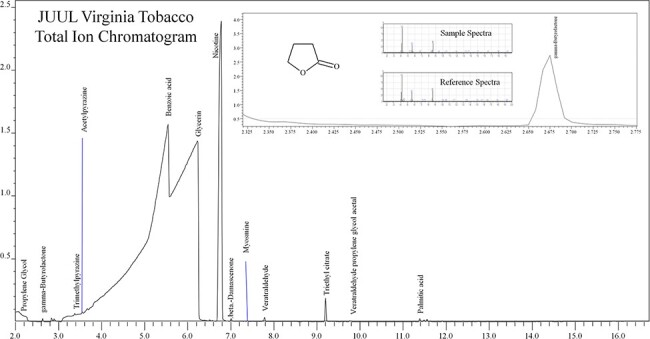

PG, VG, caffeine, menthol, nicotine and GBL were presumptively identified and later confirmed by comparing to reference standards. Figure 2 shows a typical JUUL Virginia Tobacco chromatogram produced by the untargeted screening method. Table II is a list of JUUL liquid chemical compositions identified by reference materials and/or libraries using the untargeted screening method for each labeled JUUL liquid flavor profile, with GHS classifications and reported uses of chemicals. Table II compounds in bold text indicate which ingredients were labeled versus the unlisted ingredients on the product packaging. The chemical profile of each JUUL liquid flavor varied. GBL was only identified in the Virginia Tobacco liquids, while caffeine and theobromine were identified in the Classic Tobacco and Menthol liquids.

Figure 2.

Total ion chromatogram of a JUUL Virginia Tobacco sample with GBL reference and sample mass spectra.

Table II.

Chemicals Identified in JUUL Products by an Untargeted GC–MS Screening Method

| Compounda | GHS hazard class | Uses | Classic Tobacco 5% Nic | Classic Tobacco 3% Nic | Virginia Tobacco 5% Nic | Virginia Tobacco 3% Nic | Menthol 5% Nic | Menthol 3% Nic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carriers | Glycerin | Sweetener; humectant; solvent; vehicle/carrier; emulsifier; thickener | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Propylene glycol | Humectant; antifreeze; food additive; solvent | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 1,1ʹ-Dimethyldiethylene glycol | Produced as a byproduct or coproduct of the manufacture of propylene glycol | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Nicotine and Minor Tobacco Alkaloids | Nicotine | Acute Toxic, Environmental Hazard | CNS stimulant; major component of cigarettes and often added to e-cigarette liquids | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Anatabine | Minor tobacco alkaloid | X | X | ||||||

| Cotinine | Alkaloid found in tobacco and the predominant metabolite of nicotine | X | X | ||||||

| Myosmine | Irritant | Minor tobacco alkaloid | X | X | |||||

| Additives | Benzoic acid | Corrosive, Irritant, Health Hazard | Food preservative; flavorant; used to make other chemical; used in nicotine salt formulations | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Caffeine | Irritant | CNS stimulant; anti-inflammatory and legal psychoactive | X | X | X | X | |||

| Theobromine | Irritant, Health Hazard | A purine alkaloid derived from cacao and other plants | X | X | X | X | |||

| Flavorant and Flavorant Degradation Products | 2-Butene-1-one, 1-(2,6,6-trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)- | Flavorant; found in tobacco related products | X | X | X | X | |||

| Acetylpyrazine | Irritant | Organoleptic/flavorant | X | ||||||

| Benzyl alcohol | Irritant | Organoleptic/flavorant; preservative; solvent; used as a local anesthetic; viscosity-decreasing agent | X | X | |||||

| β-Damascenone | Irritant, Health Hazard | Organoleptic/flavorant | X | X | X | X | |||

| GBL | Corrosive, Acute Toxic, Irritant | Flavorant; solvent; food stabilizer; CNS depressant | X | X | |||||

| Mentholb | Irritant | Monoterpene alcohol made synthetically or obtained from mint oils; flavorant | X | X | |||||

| Methyl palmitate | Irritant | Flavorant | X | ||||||

| Stearic acid | Irritant | aka—Octadecanoic acid; found in various animal/plant fats | X | X | |||||

| Palmitic acid | Irritant | aka—Hexadecanoic acid; flavorant; used to make food additives | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Triethyl citrate | Irritant | Ester of citric acid; food additive/stabilizer; flavorant | X | X | |||||

| Trimethylpyrazine | Flammable, Irritant | Organoleptic/flavorant | X | X | |||||

| Veratraldehyde | Irritant | aka—methylvanillin; organoleptic; antifungal | X | X | |||||

| Veratraldehyde propylene glycol acetal | Artifact of reaction between veratraldehyde and PG; organoleptic/flavorant | X | X |

Bolded compounds are listed on product.

Menthol only listed on Menthol flavored product.

Ethanol in the originally submitted Virginia Tobacco samples was found to range from 1.5 to 1.9% with an average of 1.8%. A freshly purchased Virginia Tobacco pod was found to contain an average of 3.3% ethanol. Averaged results from the nicotine and GBL quantitation can be seen in Table III, with representative chromatography depicted in Figures 3 and 4. Virginia Tobacco e-cigarette liquids were found to contain an average of 0.37 mg/mL, or 370 parts per million (ppm), of GBL in the e-cigarette liquids. To highlight pod-to-pod variability in different manufacturing lots, individual GBL pod results are described in Table III. The water from the aerosol trap contained 1 µg of GBL per one 4-second puff and confirmed GBL is aerosolized.

Table III.

Average Nicotine and GBL Concentrations in JUUL Liquids

| Product (%) | Lot | Nicotine (mg/mL) | GBL (mg/mL) [intra-lot range]a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic Tobacco 5% | HMO3NA18A | 54.7 | ND |

| Classic Tobacco 3% | HK04NA17B | 30.4 | ND |

| Classic Tobacco 3% | HG22PA09B | 34.2 | ND |

| VA Tobacco 5% | HK09GA01A | 58.7 | Insufficient to quantb |

| VA Tobacco 5% | JF12SA20A | 50.4 | 0.37 [0.37–0.38] |

| VA Tobacco 5% | GJ05GD04A | 51.1 | 0.27 |

| VA Tobacco 3% | JF07NA16B | 31.6 | 0.40 [0.39–0.42] |

| Menthol 5% | JE28CA08A | 50.6 | ND |

| Menthol 3% | JF17NA17B | 33.1 | ND |

| Menthol 3% | HG23PA06B | 35.5 | ND |

Four-packs were sampled twice.

Original submission. No e-cigarette liquid was available to sample due to pods leaking.

ND = None detected.

Figure 3.

GC–MS chromatogram produced from quantitation of nicotine, with structures and ions monitored for nicotine and quinoline.

Figure 4.

LC–MS-MS chromatograms of three JUUL pod flavors evaluated for GBL concentrations.

Discussion

Compared to targeted analyses, untargeted screening is an invaluable tool to evaluate chemical compositions of widely varied and constantly changing products, such as e-cigarette liquids which can be comprised of thousands of different combinations of flavorants, carriers, additives and pharmacologically active ingredients. PG and VG were the only carriers identified in the JUUL pods. The identification of benzoic acid concurrent with the measured concentration of nicotine confirms that this product was manufactured using nicotine salt rather than freebase nicotine. Nicotine salts are reported to produce a more mild and more pleasant sensation when inhaled compared to the freebase nicotine formulations and, therefore, are used in liquid formulations to increase the concentration of nicotine in the device while reducing the volume of the liquid (25). Myosmine is a nicotine impurity, and veratraldehyde PG acetal indicates product instability post-production. A recent study suggests that flavorant-PG adducts are rapidly formed post-production, may be stronger airway irritants than the parent compounds (26) and are reported as potentially harmful airway irritants (27, 28). While the remaining ingredients identified have flavorant properties, the identification of GBL in the liquid was unexpected, and the reason for its presence is unknown.

Evaluation of ethanol is a standard procedure for this lab due to prior findings of significant levels of ethanol in e-cigarette liquids (22). While the products evaluated in this particular study contain relatively low concentrations of ethanol, underage use of these products and unknown pharmacological effects from inhalation of ethanol is still a concern, especially with co-administration of other pharmacologically active ingredients.

PG, benzoic acid, glycerin and nicotine were the only compounds labeled on the JUUL pod packaging. None of the remaining ingredients identified were specifically labeled, aside from the menthol identified in menthol-flavored products. Product packaging simply list “flavor” as the remaining ingredient. This vague language is a cause for concern, as it enables manufacturers to change their formulations without announcement, making it difficult for health officials to track which flavorants are actively used and could be contributing to vaping-related lung injury. Most of these unlabeled ingredients attributed to providing the desired aroma and flavor profile are associated with at least one GHS classification, including corrosive, acutely toxic, irritant and environmental hazard (29). The flavoring chemicals and carriers are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the FDA, meaning “the substance is generally recognized, among qualified experts, as having been adequately shown to be safe under the conditions of its intended use, or unless the use of the substance is otherwise excepted from the definition of a food additive” (30, 31). GBL was recorded as GRAS in food products when <22 ppm in a comment to the DEA’s proposed ruling to control GBL as a List 1 chemical (32). The GHS classifications contraindicate safety for the intended use of vaping, particularly since vaping products are not considered food products. Without inhalation studies, the impact of inhaling a product containing 370 ppm of GBL is not known.

The concentration of GBL in the liquids is well below the 70% threshold identified by the DEA to be considered for regulatory control under the Controlled Substances Act. Diversion of GBL for the purposes of human consumption is considered “tantamount to diversion of a schedule I controlled substance” (32). The effects of micro-dosing GBL when vaping, with or without nicotine, is unknown, but an important concern is that GBL may enhance the abuse potential of nicotine-containing e-cigarette liquids. Co-consumption of GBL with ethanol and other pharmacologically active ingredients in e-cigarette liquid may lead to other untoward and unexpected effects.

Classic pharmacokinetic principles governing bioavailability and time to onset for pharmacological activity dictate that inhalation is a faster and more efficient route of administration than oral consumption, requiring less chemical for maximal effect. Without inhalation studies, the pharmacologic and toxicologic impacts of inhaling GBL remain unknown. A single case of ALI after chronic oral ingestion of GBL over a long period of time was reported. The patient presented in the hospital with high anion gap metabolic acidosis and acute inflammation in the lung tissue caused by chemical exposure. The physicians hypothesized the ALI was the result of GHB binding the GABAA receptor precipitating alveolar inflammation and pulmonary edema, in addition to the inhalation of small amounts of GBL over a long period of time leading to direct toxic effects to the alveoli (9).

In August of 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognized a new lung disease associated with vaping, known as e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI). Symptoms ranged from respiratory discomfort (e.g., cough and shortness of breath) to death (33). Victims demonstrated severe damage to the alveoli (34, 35). Most EVALI cases were associated with tetrahydrocannabinol vaping products found to contain vitamin E acetate. Lung tissue from some patients with EVALI was contaminated with vitamin E acetate. Other chemicals could not be ruled out from producing EVALI, especially as several victims reported to have vaped only nicotine products (34). These reported cases, the risk for complex drug–drug interactions with co-administration, and the general unknown implications of vaping GRAS chemicals underscore the need for transparent reporting of chemical constituents. Unsuspecting consumers of e-cigarette products can experience untoward and unexpected effects. Physicians may not understand and attribute the etiology of reported symptoms, leading to misdiagnoses and/or incomplete treatment regimens.

Conclusions

The identification of GBL in an e-cigarette product purportedly compliant with federal regulation continues to demonstrate public health and public safety concerns. GBL is a known irritant, corrosive agent and is acutely toxic. Untargeted chemical analyses of products intended for public consumption are critical for identifying the chemical ingredients that potentially impact health and public safety.

Contributor Information

Alaina K Holt, Department of Forensic Science, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1015 Floyd Avenue, Room 2015, Richmond, VA 23284, USA; Integrative Life Sciences Doctoral Program, Virginia Commonwealth University, PO Box 84230, Richmond, VA 23284-02030, USA.

Justin L Poklis, Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology, Virginia Commonwealth University, PO Box 980613, Richmond, VA 23298-0613, USA.

Caroline O Cobb, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University, 808 West Franklin St, Richmond, VA 23298, USA.

Michelle R Peace, Department of Forensic Science, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1015 Floyd Avenue, Room 2015, Richmond, VA 23284, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Justice [2018-75-CX-0036]; National Institute on Drug Abuse [U54DA036105] and the Center for Tobacco Products of the United States Food and Drug Administration; National Institute of Health: National Institute on Drug Abuse [P30DA033934]. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice. No funding or products were provided by JUUL Labs Inc. for any aspect of this project.

References

- 1.Hennessy S.A., Moane S.M., McDermott S.D. (2004) The reactivity of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) in alcoholic solutions. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 49, 1–10. doi: 10.1520/JFS2003340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busardò F.P., Gottardi M., Tini A., Minutillo A., Sirignano A., Marinelli E., et al. (2018) Replacing GHB with GBL in recreational settings: a new trend in chemsex. Current Drug Metabolism, 19, 1080–1085. doi: 10.2174/1389200219666180925090834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Søderlund E.135. [Gamma]-Butyrolactone (GBL). Arbetslivsinstitutet: Stockholm, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell J., Collins R. (2011) Gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) dependence and withdrawal: GBL withdrawal. Addiction, 106, 442–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andresen H., Aydin B.E., Mueller A., Iwersen‐Bergmann S. (2011) An overview of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid: pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, toxic effects, addiction, analytical methods, and interpretation of results. Drug Testing and Analysis, 3, 560–568. doi: 10.1002/dta.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snead O.C. (2000) Evidence for a G protein-coupled γ-hydroxybutyric acid receptor. Journal of Neurochemistry, 75, 1986–1996. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751986.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Expert Committee on Drug Dependence. (2014) Gamma-butyrolactone - Critical Review Report. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 8.NOAA . 4-Butyrolactone. Cameo Chemicals. https://cameochemicals.noaa.gov/chemical/19941 (accessed Mar 10, 2021).

- 9.van Gerwen M., Scheper H., Touw D.J., van Nieuwkoop C. (2015) Life-threatening acute lung injury after gamma butyrolactone ingestion. The Netherlands Journal of Medicine, 73, 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Justice. (2010) Final Rule: Exempt Chemical Mixtures Containing Gamma-Butyrolactone. Federal Register, 75, 37301–37307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CBHSQ Data . (2018) National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Releases. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2018-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases (accessed July 2, 2020).

- 12.Thurtle N., Abouchedid R., Archer J.R.H., Ho J., Yamamoto T., Dargan P.I., et al. (2017) Prevalence of use of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) to vape recreational drugs by club patrons in South London. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 13, 61–65. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0583-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter L.P., Koek W., France C.P. (2009) Behavioral analyses of GHB: receptor mechanisms. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 121, 100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bigelow B.C. (ed.). (2006) GBL in UXL Encyclopedia of Drugs and Addictive Substances, pp. 348–360.

- 15.Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Justice. (1998) Industrial Uses and Handling of Gamma-butyrolactone; Solicitation of Information. Federal Register, 63, 56941–56942. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tateo F., Bononi M. (2003) Determination of gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) in foods by SBSE-TD/GC/MS. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 16, 721–727. doi: 10.1016/S0889-1575(03)00067-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oser B.L., Hall R.L. (eds). (1972) GRAS Substances in Recent Progress in the Consideration of Flavoring Ingredients Under the Food Additives Amendment. Institute of Food Technologists, pp. 35–42.

- 18.Burdock G.A., Fenaroli G.. Fenaroli’s Handbook of Flavor Ingredients. 5th edition. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO | JECFA . https://apps.who.int/food-additives-contaminants-jecfa-database/chemical.aspx?chemID=1374 (accessed Feb 23, 2021).

- 20.Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Justice . (2012) Definitions Relating to Listed Chemicals. Code of Federal Regulations, 11–14.

- 21.Pagano T., DiFrancesco A.G., Smith S.B., George J., Wink G., Rahman I., et al. (2016) Determination of nicotine content and delivery in disposable electronic cigarettes available in the United States by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 18, 700–707. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poklis J.L., Wolf C.E., Peace M.R. (2017) Ethanol concentration in 56 refillable electronic cigarettes liquid formulations determined by Headspace Gas Chromatography with Flame Ionization Detector (HS-GC-FID). Drug Testing and Analysis, 9, 1637–1640. doi: 10.1002/dta.2193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peace M.R., Mulder H.A., Baird T.R., Butler K.E., Friedrich A.K., Stone J.W., et al. (2018) Evaluation of nicotine and the components of e-liquids generated from e-cigarette aerosols. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 42, 537–543. doi: 10.1093/jat/bky056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin S., Ning X., Cao J., Wang Y. (2020) Simultaneous quantification of γ-hydroxybutyrate, γ-butyrolactone, and 1,4-butanediol in four kinds of beverages. International Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2020, 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2020/8837743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harvanko A.M., Havel C.M., Jacob P., Benowitz N.L. (2020) Characterization of nicotine salts in 23 electronic cigarette refill liquids. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 22, 1239–1243. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erythropel H.C., Jabba S.V., DeWinter T.M., Mendizabal M., Anastas P.T., Jordt S.E., et al. (2019) Formation of flavorant–propylene glycol adducts with novel toxicological properties in chemically unstable e-cigarette liquids. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 21, 1248–1258. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherwood C.L., Boitano S. (2016) Airway epithelial cell exposure to distinct e-cigarette liquid flavorings reveals toxicity thresholds and activation of CFTR by the chocolate flavoring 2,5-dimethypyrazine. Respiratory Research, 17, 57. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0369-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behar R.Z., Luo W., McWhirter K.J., Pankow J.F., Talbot P. (2018) Analytical and toxicological evaluation of flavor chemicals in electronic cigarette refill fluids. Scientific Reports, 8, 8288. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25575-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.PubChem . National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed Mar 11, 2021).

- 30.FEMA . About FEMA GRAS Program. https://www.femaflavor.org/gras#concept (accessed May28, 2020).

- 31.Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . (1983) Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act, Sections 201 and 409.

- 32.Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Justice . (2008) Exempt Chemical Mixtures Containing Gamma-Butyrolactone. Federal Register, 73, 66815–66821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chatham-Stephens K., Roguski K., Jang Y., Cho P., Jatlaoui T.C., Kabbani S., et al. (2019) Characteristics of hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients in a nationwide outbreak of E-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury — United States, November 2019. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68, 1076–1080. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6846e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blount B.C., Karwowski M.P., Shields P.G., Morel-Espinosa M., Valentin-Blasini L., Gardner M., et al. (2020) Vitamin E Acetate in Bronchoalveolar-Lavage Fluid Associated with EVALI. New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 697–705. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30321-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reagan-Steiner S., Gary J., Matkovic E., Ritter J.M., Shieh W.-J., Martines R.B., et al. (2020) Pathological findings in suspected cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI): a case series. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8, 1219–1232. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30321-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]