Abstract

Background

COVID-19 has become a worldwide pandemic impacting child protection services (CPSs) in many countries. With quarantine and social distancing restrictions, school closures, and recreational venues suspended or providing reduced access, the social safety net for violence prevention has been disrupted significantly. Impacts include the concerns of underreporting and increased risk of child abuse and neglect, as well as challenges in operating CPSs and keeping their workforce safe.

Objective

The current discussion paper explored the impact of COVID-19 on child maltreatment reports and CPS responses by comparing countries using available population data.

Method

Information was gathered from researchers in eight countries, including contextual information about the country’s demographics and economic situation, key elements of the CPS, and the CPS response to COVID-19. Where available, information about other factors affecting children was also collected. These data informed a discussion about between-country similarities and differences.

Results

COVID-19 had significant impact on the operation of every CPS, whether in high- income or low-income countries. Most systems encountered some degree of service disruption or change. Risk factors for children appeared to increase while there were often substantial deficits in CPS responses, and in most countries there was at a temporary decrease in CM reports despite the increased risks to children.

Conclusions

The initial data presented and discussed among the international teams pointed to the way COVID-19 has hampered CPS responses and the protection of children more generally in most jurisdictions, highlighting that children appear to have been at greater risk for maltreatment during COVID-19.

Keywords: Children, Child maltreatment reports, Child protective service (CPS) responses, COVID-19

1. Introduction

Children and young people are particularly affected by the responses to COVID-19, including school closures, restrictions on sport and leisure activities, etc. In a review of mental health impacts of the pandemic, Sher (2020) found that the psychological sequelae would likely persist for months and years. Key mental health issues include distress (depression, anxiety, substance use, suicidality, insomnia) and fear of contagion. In an online survey of more than 2000 (U-Report, 2020), 85 % were “worried about the future” (most were male). Oosterhoff and Palmer’s (2020) population-based survey of US youth found most youth not engaging in social distancing, but monitoring news and disinfecting daily.

In addition, the lives of children can be significantly impacted when family members and other adults are infected or are dying, or when family members or caretakers are retrenched as a result of lockdowns, since the economic crisis might linger longer than the health crisis consequences and have detrimental effects on many families (Gromadai, Richardsoni, & Rees, 2020). Even if they are not directly affected, children will be inevitably impacted by the response to the virus, in particular being restricted to their homes.

In their analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic, UNICEF (2020b, 2020b) identified three main potential secondary impacts on children and their caregivers in term of child protection: neglect and lack of parental care; mental health and psychosocial distress; and increased exposure to violence, including sexual violence, physical and emotional abuse. Another serious concern is the high levels of exposure to the internet (e-Safety Commissioner (Australia), 2020). The international 2020 survey by U-Report (2020) found that 47 % of participants under 19 reported increased negative experiences online (cyberbullying, inappropriate content, hate speech, harassment, and unwanted contact) as COVID has increased screen time.

Combined, some refer to these impacts as the “secondary pandemic” of child neglect and abuse (Adams, 2020). The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action stated that pandemics damage the environment in which children live, therefore increasing their susceptibility to abuse, neglect, violence, exploitation, psychological distress and impaired development (Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, 2019b, 2; Fischer, Elliott, & Lim Bertrand, 2018, 9–10).

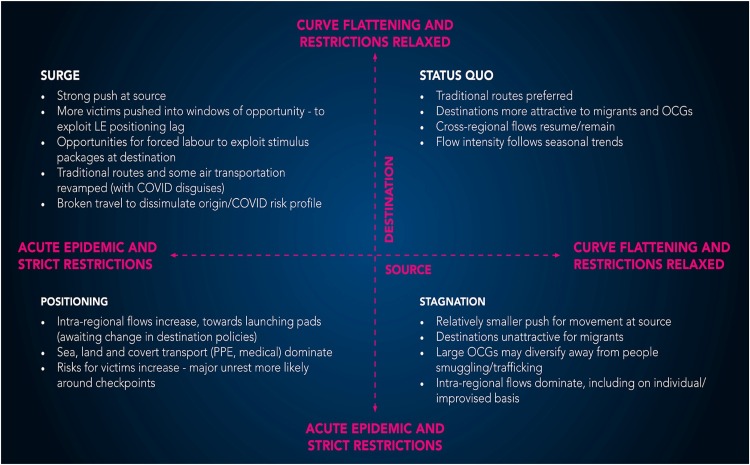

The most serious concerns for child neglect are related to food insecurity, exacerbated by COVID-19 due to disruption of employment and access to food supply; perceived risk to and fear of COVID-19 contagion; and overcrowded housing due to lockdown. The most serious concerns for child sexual abuse and exploitation are the pandemic’s relationship to the commercialization of humans. For example, Interpol (2020) outlined the short- and long-term interaction between COVID-19 and human trafficking. Organized crime and predatory actions that come with opportunity have Interpol projecting that migration away from disease centres will increase illegal migration. COVID-19 misinformation, moreover, is exploited by traffickers to increase charges to migration and to increase risks to slavery.

Fig. 1 illustrates the various risks that emerge during COVID-19. All these elevated risks pose significant challenges to the way child protection services (CPSs) can contend with protecting children from maltreatment during COVID-19. As seen in the figure, there are implications to the acute phase of the viral infection, and then when lockdowns and restrictions are relaxed. Some of these risks are likely to persist even after the pandemic has abated, due to its likely ongoing financial implications. Interpol (2020) indicates that the “ongoing economic consequences of the pandemic are likely to put more people at risk of becoming victims”.

Fig. 1.

Potential Risks along the COVID-19 Response “Lifecycle”.

Recent studies point to a decrease in official CM referrals during COVID-19 lockdowns and school closure (e.g., Garstang et al., 2020), with child educators being the mandated reporters who have been found to display the highest decrease in the CM report rates (Baron, Goldstein, & Wallace, 2020). Simultaneously, online testimonials of CM (Babvey et al., 2020), physical injuries in pediatric settings (Garstang et al., 2020) and calls to helplines have drastically increased (Petrowski, Cappa, Pereira, Mason, & Daban, 2020). These initial findings points into the question on the way CPS responses were effected by COVID-19 as well as by its impact on children disappear from the public gaze due to forced lockdowns.

1.1. Child protection services

Child protection in the context of humanitarian crises involves the “prevention of and response to abuse, neglect, exploitation and violence against children” (Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, 2019a, 19). CPSs provide support and care for both children and parents in a range of different contexts; however, COVID-19 represented a challenging response for most CPSs. Protocols for safe service provision needed to be quickly established in most jurisdictions. For example, in some jurisdictions where a youth would have aged out of care during the pandemic, pauses were put in place to allow for ongoing youth support. Similarly, face-to-face visits to birth families have been restricted during COVID-19 lockdowns (e.g., Katz & Cohen, 2020). CPS workers, like other frontline workers, are at increased COVID-19 risks to when in direct contact with children and families.

During COVID-19, various countries have been reporting on their attempts to innovate quickly (International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse & Neglect, 2020). However, there is gold standard for addressing the challenges of COVID-19 in such a short time and the current process rests on information exchange of local data. COVID-19 could potentially impact CPSs in a number of ways, depending on how the virus has affected a particular country, the overall response of the country, including lockdowns, school closure, travel restrictions, the state of a country’s economy pre-COVID 19 the nature and resourcing of the CPSs themselves and the legislative frameworks in which they operate.

With such varied and fluid contexts, a systems approach would seem to be the most appropriate for conceptualizing CPS in the time of COVID-19. Note that the responses themselves are fluid and ever changing: lockdowns could last for a couple of weeks or several months, and could be reinstated in subsequent waves of infection (Katz & Cohen, 2020). Thus, any snapshot of the CPS response will inevitably provide an incomplete picture and will only reflect the situation to that point. Nevertheless, these descriptions provide important insights into the similarities and differences in how systems across international borders have responded to this unprecedented crisis.

1.2. Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework used for this discussion paper is the open systems approach (Wulczyn et al., 2010). Child protection systems are understood as open systems that interact with a range of other systems in particular health, education and justice. The CPS also operates within the country’s overall political, legal, socioeconomic and cultural context. COVID-19 is an external shock that will have immediate, medium and longer-term impacts on the system and on the way the system responds to child maltreatment (CM). Thus the response of the CPS must be seen within the context of the broader service system and overall economic and policy context. For example, initiatives such as closing schools may impact on reports to the CPS by reducing children’s access to mandatory reporters. More distal impacts are also likely to be felt, including, as indicated above, the flow on effects of the economic impact of COVID-19 on families, which is likely to increase risk factors for children and therefore, in the medium term, increase reports to the CPS. COVID-19 is also likely to have impacts on the CPS workforce, particularly if key workers become ill or have to quarantine for extended periods.

1.3. The current discussion

The current discussion paper wishes to joint recent efforts in the field of CM in order to better adhere to the way COVID-19 is impacting CM reports as well as CPS responses at different stages in different jurisdictions. This paper was designed as an initial platform for generating a discussion informing international reflection, based on initial data from eight countries, including anecdotal reports and grey literature, aiming to provide an initial understanding of the COVID-19 impact on CM.

2. Method

The authors collected data for each jurisdiction in the study according to a template that provided contextual information, including demographics and economic circumstances, policy responses to COVID-19, and specific CPS responses. Data were collected mainly from publicly available sources such as government statistical agencies and reports from child protection organizations and other systems. For some countries, raw data were available for inclusion by the research team, but in most countries, aggregate data were provided by the agency. In some cases, data were sourced from media and other reports where data not available directly from the agencies. The template was completed by each research team by July 2020 and reflected the most up-to-date data available at that point. In many cases these are preliminary data which are subject to revision. The countries represented here were self-selected out of a collaboration group of child protection researchers convened by the second author. Researchers in this collaboration who had access to sufficient information in July 2020 contributed to the findings. In some countries (for example Australia and Canada) there is no national CPS, and child protection is devolved to a lower level of governance such as states or provinces. In these cases the data were sourced from particular jurisdictions in the country, although the overall country context is provided in the General Country Backgrounds section. Ethical permission was not sought as the data provided to the authors were all in the public domain.

3. Findings

3.1. General country backgrounds

In order to set the ground for the international discussion, a context of each of the participating countries is introduced. Table 1 provides an overview of each country's population, data with respect to children, as well as economic information. When considering the unique circumstances of each of the countries, a range of principal challenges were identified by the researchers, as elaborated below.

Table 1.

Demographics and Economic Circumstances by Jurisdiction.

| Australia | Brazil | Canada (Quebec) | Canada (Ontario) | Colombia | Germany | Israel | South Africa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 25,364,300 | 211,726,360 | 8,522,800 | 14,750,000 | 48,258,494 | 83,000,000 | 9,136,000 | 58,780,000 |

| Population under 18 | 4,670,000 (18.69 %)* | 52,550,485 (24.82 %) | 1,763,147 (20.68 %) | 2,681,780 (18.18 %) | 10,906,419 (22.6 %) | 13,600,000 (16.38 %) | 2,960,000 (32.07 %) | 17,840,000 (30.35 %) |

| Infant mortality rate | 3.1 per 1000 live births | 12.40 per 1000 live births | 4.1 per 1000 live births | 4.9 per 1000 live births | 14.2 per 1000 live births | 3.1 per 1000 live births | 3.1 per 1000 live births | 28.5 per 1000 live births |

| GDP per capita | 57,363 USD | 8,921 USD** | 46,392 CAD | 39,605 USD | 6,216 USD | 41,346 Euro | 36,250 USD | 6,354 USD |

| Gini coefficient | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 31.1 | 0.35 | 0.62 |

Note: *Under 15; **2018.

3.1.1. Australia

Australia is a rich country with a very diverse population of just over 25 million people. More than half the population has at least one parent born overseas. The country is geographically very large, but the majority of the population live in five major cities. Like many rich countries, the population is ageing; in the 20 years between 1999 and 2019, the proportion of children decreased from 20.9 %–18.7 % of the total population (ABS, 2019). An ongoing major challenge is inequality, with the Gini coefficient being 0.34 (ACOSS & UNSW, 2018). An ongoing issue is the effects of colonialism on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who have lower life expectancy, higher rates of incarceration and are disadvantaged in the education, health and child protection systems (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). Some migrant populations are also very disadvantaged, in particular refugees. Another major challenge is climate change and the social consequences of drought and bush fires. Australia is a very geographically diverse country and people living in remote areas have low levels of access to supports and services. Data in this article are sourced from New South Wales (NSW) which is the largest state in Australia with a population of just over eight million people, of whom over five million live in Sydney metropolitan area.

3.1.2. Brazil

There are three major challenges in Brazil: the economy, violence, and governmental authoritarianism. The country has faced an economic crisis since 2014, with few signs of recovery. Recent government data show a 12.9 % unemployment rate and 13.5 million being characterized as in extreme poverty; 4.9 % of the workforce is in a state called desalento (despondent). A worker is considered despondent when they have stopped active searching for work due to lack of opportunities (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2020).

Another major social issue Brazil faces is rampant violence in many areas of the country. Homicide rates range from 10.3 and 62.8 per 100,000 inhabitants (Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, 2019). This is a decrease compared to 2010. Still, even the lower rate is much higher than in Canada (1.76), the US (4.96), or Russia (8.21). These homicide rates are particularly high for young males (15–29 years): 69.9. In 2017 alone, violence was responsible for the death of over 35,000 young males.

Finally, the Brazilian government uses authoritarian discourse, providing illusion as a solution for the problems that society is facing (Chagas-Bastos, 2019). This has led to an increase in negative views regarding democracy, with more Brazilians believing that an authoritarian regime or a democracy would not have a major effect on their lives (Hunter & Power, 2019). Public polls in 2020 show an increase in democracy support (DataSenado, 2020), but still many authors describe current dangers for rights for indigenous and other minorities and regarding racial issues (Chagas-Bastos, 2019; Hunter & Power, 2019).

3.1.3. Canada

Canada is a relatively rich country with a high average income. The country is very diverse with large numbers of migrants. Like other colonial countries the Indigenous populations of Canada have suffered from the effects of colonialism and discrimination. In Ontario, based on the latest data available, approximately 410,000 or 15.4 % of children live in poverty. This is an increase of 28,000 or 1.0 % compared to the previous year.

In Quebec, 8.7 % live below the poverty line, a number that has shrunk substantially in the last five years. The period prior to COVID-19 was essentially a good one economically in Canada, including Quebec. In addition, Quebec has been welcoming refugees from Central and Western Africa, Haiti and the US (mostly Latino and Haitian individuals concerned about US laws regarding them).

3.1.4. Colombia

Income inequality in Colombia is one of the highest in the world, with a Gini coefficient of 50.3 (World Bank, 2018) and with 27 % of the population living below the poverty line (World Bank, 2020). Additionally, there is high social inequality amongst Indigenous and Black communities and people with disabilities (UNICEF, 2014). According to the last national census, in Colombia 4 % of the population are from Indigenous communities and 9 % are from Black communities (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, 2018). Colombia is still struggling with the 50-year war between the government and guerrilla groups, which has left over 220,000 people dead (Fajardo-Cely, 2014). A 2019 report states that Colombia has eight million internally displaced persons, ranking it the highest in the world (UNHCR, 2019). According to a national report, some 2.4 million children and adolescents are direct victims of the armed conflict (Unidad para las victimas, 2015). A recent study found that different forms of community violence, such as homicide rates and the presence of guerrillas were associated with the use of physical punishment (Cuartas, Grogan-Kaylor, Ma, & Castillo, 2019).

3.1.5. Germany

Germany is a rich country and relatively equal compared to other countries in the OECD, with a Gini coefficient of 0.29 (OECD, 2020) The principal challenges in Germany are demographic transformations, ageing population, right-wing extremism and terrorism, refugees, the threat to European cohesion, digitalization, foreign policy, climate change, and the social and financial gap between rich and poor, and the former East and West Germany.

3.1.6. Israel

Israel is a multicultural society, with Jews and Palestinian-Arabs being the two prominent groups that live together in a continuous conflict as well as tremendous gaps. Although Israel is a Western industrialized society with mostly individualistic values, it is more communal and more collectivist than the US (Mayseless & Salomon, 2003; Sagy, Orr, Bar-On, & Awwad, 2001), with strong emphasis on the social role of the family (Lavee & Katz, 2003) and the importance of the collective. Arabs and ultraorthodox Jews are by far the poorest communities in Israeli society. Note also that Israel is characterized by deep political and racial divides that greatly impact allocation of resources to welfare.

3.1.7. South Africa

South Africa’s Gini coefficient – 0.62 – makes it one of the least equal countries in the world (Posel & Rogan, 2019). Historical inequality stemming from a pre-democratic, apartheid system is exacerbated by skewed income distribution, unequal access to opportunities, rising unemployment, as well as low economic growth (Fouché, Truter, & Fouché, 2019; Nattrass & Seekings, 2001). Prior to the lockdown, approximately 17–18 million South Africans were reliant on social grants for their household income and food security, including 12.5 million relying on child support grants.

High levels of violence are pervasive in the country, including sexual abuse of children (Artz et al., 2016) and some of the highest levels of gender-based violence in the world, with 250 of every 100,000 women suffering sexual assaults, compared to 120 of every 100,000 men in 2016/2017 (Maluleke, 2018). South Africa is known for its high incidence of rape, and is often referred to as the “rape capital of the world” (Lamb, 2019; Maluleke, 2018; Matzopoulosa et al., 2020).

Finally, more than a quarter of children under five years are stunted. Research published in Lancet shows that South Africa is one of only 20 countries accounting for 80 % of the world’s stunted children, with stunting being the most common form of malnutrition in the country (Zere & McIntyre, 2003). In 2018, undernutrition was associated with 58 % of child deaths.

3.1.8. Conclusion

The countries involved in this study vary dramatically in their political, economic and social contexts. Whereas Brazil, Colombia, and South Africa struggle with poverty, inequality and dramatic rates of violence, Australia, Canada, and Germany are amongst the most prosperous countries in the world, with comparatively generous welfare provision and a good quality of life, although they all include disadvantaged populations. Israel lies between these two ends of the continuum, and although it is not characterized by extreme poverty, the country is in continuous conflict and political strife that damage its societal dynamics and welfare policy. All countries have considerable levels of inequality, although some are much more unequal than are others.

3.2. Child protection services in the participating countries

Table 2 illustrates the characteristics of each country with respect to its CPS system, including the issue of mandatory reporting. As can be seen from the table, most of the countries (except Germany) require mandatory reporting of CM. Specific provisions vary, however: in Australia (New South Wales) and Brazil, only professionals are mandatory reporters, while in Canada, Colombia, South Africa and Israel all adults are mandated to report CM.

Table 2.

CPS Features per Jurisdiction.

| Australia | Brazil | Canada Quebec | Canada Ontario | Colombia | Germany | Israel | South Africa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centralized/Decentralized | Centralized (in each state) | Centralized | Decentralized | Decentralized | Centralized | Centralized | Centralized | Centralized |

| Mandatory reporting | Yes for specified professionals (teachers, doctors, nurses, early childhood educators) | Yes for all child-serving professionals since 1988 | Yes for everyone | Yes for everyone, since 1965 in Ontario and then for all provinces | Yes for everyone, since 2006 | No | Yes for everyone, since 1989 | Yes for everyone |

A key issue for the current discussion is how data are collected in each CPS. In some countries, there is an agency responsible for collecting and publishing the data at regular intervals. In Germany, for example, it is the Youth Welfare Offices; in Israel, it is the Ministry of Welfare, as well as the National Council for the Welfare of the Child, an NGO that collects and publishes annually detailed data on children. In Australia New South Wales publishes quarterly and annual reports, some of which are disaggregated geographically. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and the Productivity Commission publish data on each Australian jurisdiction annually, generally not disaggregated except by metro versus rural/remote. Monthly data has been used within the Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ) in NSW and shared with other agencies during COVID. Nationally, monthly data was published in Australia in early 2021 (AIHW, 2021). In Canada, data are available year round. In Colombia, the Mission Information System of the Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF) provides, for each case, the basic data and description of the current situation of the child or adolescent (ICBF, 2016). Since 1991, Brazil has provided a dataset called Datasus (Brazil, 1991), with mortality and morbidity information about all its residents, including reports on violence through the healthcare system. Finally, in South Africa there is no central data collection process. Data on CM is collated from grey literature (media reports, legal documents) and interviews with local non-government and government child protection social work managers.

3.3. COVID-19 responses

For all countries, the COVID-19 response included social distancing, lockdowns and system shutdowns. Table 3 elaborates on the characteristics of each country in the initial response to the pandemic. For Australia (NSW), Canada, Germany, and Israel, this period was from March to May. For Brazil, Colombia and South Africa, strict guidelines were still in place in July when the data were collected. At the time of writing, some jurisdictions, e.g. Victoria, (another Australian state) and Israel, have had a second wave of infections and some restrictions have been reimposed. As can be seen from Table 3, parallel to the common responses to COVID-19, there was a wide variety in the support provided by the government to the citizens overall and for children and families more specifically. This variance is even more evident in the various CPSs’ responses during COVID-19.

Table 3.

Country Responses to COVID-19.

| Australia | Brazil | Canada | Colombia | Germany | Israel | South Africa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quarantine | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Preschools shut down | Partially | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Schools shut down | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Government economic support programs | Businesses & unemployed | Low-income families & unemployed | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes, but dissemination not clear |

3.3.1. Child protective services’ responses during COVID-19

Although every country implemented policies to prevent the spread of COVID-19, they differed considerably in relation to the implementation of policies specifically oriented to protecting children from maltreatment. As indicated above, COVID-19 and government responses have the potential for significantly affecting not only children’s wellbeing but also the operation of frontline services such as child protection workers. This section describes each country’s policy with respect to CPSs and in particular whether dedicated resources have been allocated to CPSs, and whether specific protocols have been created to address the challenges unique to COVID-19.

3.3.1.1. Policy on CPS

In Australia (NSW), Canada (ON, QC) and Germany, the initial response to the COVID-19 involved forced shutdown of services, including the court system in NSW. However, statutory social services including CPS were excluded and defined as essential services, with their workers considered front line workers. An extraordinary example for a policy prioritizing the protection of children can be found in Germany, where the Youth Welfare Offices (Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft der Landesjugendämter) ensured that they continued to protect children and support families: "When in doubt, child protection comes first". Despite drops in reports, child protection workers in NSW in Australia continued to see children at the same rate as pre-COVID using direct contact wearing PPE or via video if warranted. This meant that the proportion of children seen face-to-face actually rose slightly during this period. This response is in contrast to policies in Colombia, Israel and South Africa, where the initial decision was to significantly reduce the scope of the social services and social workers were defined as non-essential.

However, even in Germany, with the starting time varying from the federal to the state levels, but ultimately nationwide, schools, kindergartens and playgrounds were closed and contact restrictions were imposed on the individual household. For a long time, the living situation of families, children and adolescents was not in the focus of policymaking (Verweis JuCo & KiCo). Child and youth welfare was also not classified as systemically relevant at first. As a result, many child and youth welfare workers were no longer available, because they had to take care of their own children at home. The already understaffed social services were thus forced to reduce themselves to the most urgent and necessary measures and cases (United Services Trade Union, 2020).

In Israel, the first government step was to shut down all social services nationwide, including the CPS. This also included closure of some residential care for at-risk children, reuniting them with their abusive families with little preparation, no supervision, and no follow-up. Contrary to government guidelines, some municipalities decided that the welfare system was essential and therefore continued to provide services during the quarantine. Only several weeks into the quarantine, following increased reports of domestic violence and growing numbers of women murdered by their spouses, did the government declare that social services including CPSs, and their workers, were essential.

In South Africa, during Level 5 lockdown in March-April, considered one of the world’s strictest, social work was not considered an essential service and thus there was a significant disruption in the CPS. No home visits were conducted and few children were either removed from parental care or placed into alternative care. Alternative care facilities were hampered by difficulties with renewing registrations, receiving funding and limited support from the Department of Social Development (DSD), resulting in inability to admit children in need into care facilities (Wolfson-Vorster, 2020). When CPS workers were eventually allowed to work, many were hesitant, which hampered service delivery further. This made effective service delivery, especially under very restrictive conditions, almost impossible, according to anecdotal reports and other media sources (Bega, Smillie, & Ajam, 2020).

The adverse impacts of inadequate policy towards the protection of children are illustrated by the South African response, in which the protection of children in government hospitals during the pandemic has become a point of serious concern. In one case, a two-year-old girl who tested positive for COVID-19 was committed to a government hospital and, as reported by Tanno (2020), allegedly raped while in quarantine. This attests to the previously described rape culture of South Africa, underlining the dangers and risks posed to children in South Africa – and elsewhere – whilst enduring a pandemic such as COVID-19.

3.3.1.2. Allocation of resources to the CPS

These policies had major impact on the allocation of resources to the protection of children during COVID-19. For example, in Quebec City, all caseworkers received iPads or laptops to engage parents through Zoom or Skype meetings. It was the responsibility of caseworkers to use these tools to maintain contact with their families, and the organizations supported them with the resources they needed to ensure this aim. Laptops and tablets were also used to help biological parents maintain contact with children placed in foster families or otherwise out of home care.

The South African government led a number of initiatives to support South Africans during lockdown. To support communities most in need, the government announced an increase in social welfare grants. For example, monthly foster child grants were increased to R1,040 per child and care dependency grants were increase to R1,860 (about $60 and $110, respectively). The DSD announced that they would recruit an additional 1,809 social workers to reinforce the current workforce and provide a range of services (The Citizen, 2020). To support schoolchildren and ensure access to education, the national Department of Basic Education, together with provincial authorities, prepared online and broadcast support resources comprising subject content with a focus on grade 12 learners and the promotion of reading for all grades.

3.3.1.3. Adapted or unique protocols created for COVID-19

It is of crucial importance to stress that for all countries, protecting children during COVID-19 created enormous challenges for CPSs, as most of their interactions and intervention efforts were required to be conducted online and the transformation from face to face provision was in all cases very rapid. In some countries, such as Australia Canada and Germany, there were specific instructions and guidelines for the protection of children during the pandemic.

In NSW, despite the lack of any official federal government response on child protection in the public domain, state-based CPSs have responded quickly and adapted to COVID-19, providing advice for carers, birth parents and mandatory reporters. For example, New South Wales provided online guidance for reporters, carers and other stakeholders in the CPS (New South Wales Department of Communities and Justice, 2020a, 2020b). In addition, a series of guidance documents were produced for CPS caseworkers to address issues such as home visits, conducting assessments, culturally sensitive practice and responding to domestic violence. As in most of the other countries, this included children in care having reduced face to face contact with birth parents and specific guidelines for mandatory reporters, encouraging them to report online as opposed to phoning the helpline.

In Brazil, federal agencies did not publish specific rules or protocols. The National Council on Children and Adolescents Rights (CONANDA, 2020) published recommendations for government agencies. This guideline suggested the adoption of emergency measures to ensure children’s rights were being upheld. It also aimed to ensure continuous CPS work during the pandemic as a buffer effect for CM cases. However, these efforts did not lead to actual changes in practices by professionals or even funding for their needs. Finally, new open channels for reporting CM and family violence were created, with a mobile app added to the existing phone numbers.

In Quebec, the CPS identified several aims for operating during COVID 19. The first was to ensure the safety of children and at the same time maintain the connection between the CPS and families: caseworkers were encouraged to make home visits while complying with social distancing procedures. Inevitably, home visits led to high levels of concern for family and child wellbeing. Also, much of the work involved helping parents develop routines and activities with the children who were now at home continuously. A major issue involved children and youth’s access to screen time and gaming.

In Ontario, some agencies, such as Dnaagdawenmag Binnoojiiyag Child & Family Services, which focuses on protecting Indigenous youth, had to adapt their service. “At the beginning of the pandemic measures, we went to virtual ways of connecting, as well as through windows, through doors, in driveways, in yards,” executive director Amber Crowe told CTV News (Haines & Jones, 2020). “But now we are reinstating in-person services on a wider basis and we are having to use PPE [personal protective equipment] in some circumstances.” Many agencies reported serving families through virtual technology. Although agencies across the province have modified their business practices to respond to health and safety concerns, their core protection services continue (Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies, 2020).

In Colombia, the ICBF has published more than 12 official administrative resolutions, guidelines, protocols and memorandums to address the COVID-19 crisis within the CPS. This has resulted in some major adjustments including restricting all family visits and interventions, prioritizing online or telephone meetings/interventions, postponing non-urgent medical appointments, suspending new adoption processes, and adapting the follow-up protocols (ICBF, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d).

Moreover, a specific health guideline has been developed to guide foster care families and protection institutions in preventing new infections. For each Colombian region, there is now a specific health protocol in case children, families, or ICBF staff members become infected (ICBF, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d). On 26 June, the ICBF Director published the most recent memorandum (ICBF, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d), reporting a significant increase in infection rates within the CPS and encouraging workers, institutions and foster care families to comply with health protocols. One of the main aspects addressed in this new memorandum was permitting family visits to children in foster care under strict health protocols.

In Germany, new and creative ways were developed to address child protection. These included “window visits” or formats such as "walk and talk", i.e. walks together in the fresh air while complying with social distance – innovative solutions developed by CPS staff during the crisis.

3.4. Child maltreatment reports during COVID-19

3.4.1. Child maltreatment reporting characteristics

3.4.1.1. NSW

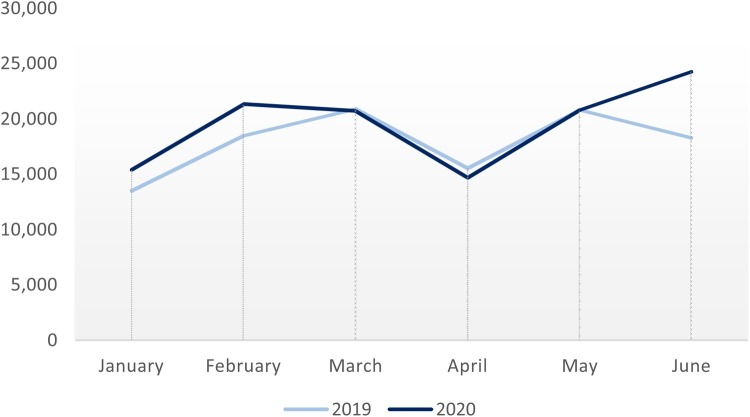

The New South Wales Department of Communities and Justice, which is responsible for the CPS in that state, produced monthly reports for internal purposes and shared with other agencies within NSW. Data was available for daily for operational purposes. The reports include a range of information about service provision including information about child protection. Overall, the figures (albeit preliminary and subject to change) confirm an increased number of reports at the beginning of the year, compared to 2019, followed by a slight drop in reports when the restrictions began, with a particular drop in reports from schools, and an increase as restrictions were lifted. Although the drop in reports in April was similar, reports in June 2020 rose compared to those in May, in contrast to 2019 when reports fell. Most recently, in the week ending on 28 June, the reports showed that:

-

•

As the children returned to face-to-face schooling, the number of e-reports increased by 27 % in June, representing a 44 % increase from June 2019.

-

•

The number of reports received by the Child Protection Helpline started to drop in the week ending 14 June, showing a similar result to 2019 by the end of June (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Risk of Significant Harm Reports, New South Wales Department of Communities and Justice.

Source: FACSIAR, NSW Department of Communities and Justice, unpublished data

3.4.1.2. Brazil

Data regarding CM during COVID-19 is still unclear, since there are no official data published in the pandemic period. Local media reports indicate a substantial increase in some areas, although it is still too soon to confirm that there has been a countrywide increase. A government agency providing a channel for human rights violations revealed a 17.1 % decrease in child abuse reporting since the pandemic and quarantine measures began (Ouvidoria Nacional dos Direitos Humanos, 2020). In past years, schools have been important reporters of CM. With school closures because of the pandemic, it likely that the lack of contact with teachers, counsellors, and principals has correlated with a decrease in CM reports, as in many of the countries included herein. Although it is too soon to confirm any CM trends in Brazil, concerns have been by NGOs, professionals, and policymakers regarding non-reporting and an increase in victimization have been widely discussed in the media and public.

3.4.1.3. Canada

Police forces and child welfare agencies across the country say overall volume of suspected child abuse reports has dropped between 30 % and 40 % (Powell, 2020).

3.4.1.3.1. Quebec

According to data from one Montreal child protection agency, from mid-March to the end of May 2019, the Director of Youth Protection received 2473 reports. Over the same period in 2020, only 1647 reports were received, representing a decrease of 33.4 %. Mauricie-Centre-du-Québec, a region between Montreal and Quebec City documented reports between March 16 and the end of May. For Quebec City, from 2019 to 2020, there was an overall reduction of 23.5 % in child protection reports; specifically, reports dropped by 25,8%, 30,7%, and 32,4% in March, April, and May, respectively, but June 2020 was almost the same as June 2019 as lockdown had essentially ended.

Usually, about one abandoned child is reported per year, but during the COVID crisis, there were seven (between 16 March and end of June). Neglect reports dropped by 21.7 %; physical abuse by 40.5 %; sexual abuse by 36.0 %; and conduct problems by 34.7 %. Psychological maltreatment reports increased by 4.6 % during this time. Reports by individual citizens increased by 11.8 %; reports by parents increased by 31.0 %; and reports by neighbours or family acquaintances increased by 12.1 %. Overall, professionals dropped their reports by 32.4 %; school personnel by 70.3 %; the police by 18.4 %; and child protection workers by 2.1 %. Other social services’ workers increased their reporting by 4.8 %.

Data from one Montreal child protection agency indicated that the decrease is directly attributable to the drop in reports made by teachers and school professionals. In 2019, 32 % of all reports received by the Director of Youth Protection came from school or day-care settings, compared to only 8 % for the same period in 2020.

In May 2020, the wait for youth protection services in Quebec was reported at a historic low, and the Junior Health Minister said credit should go to the government's recent $65 million investment into the system. But experts and union officials believe the decrease is more likely due to the pandemic, which has closed many of the usual facilities where children in need of help are identified. Indeed, Université du Québec en Outaouais Professor Marie-Ève Clément, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Violence against Children, said empty waiting lists were more likely to be the consequence of restrictions imposed due to COVID-19, leading to decrease opportunities to observe and report potential maltreatment (Nakonechny, 2020).

3.4.1.3.2. Ontario

One child protection agency has received reports about 27 children from teachers during the pandemic. During the same time last year, there were 158 such referrals (White, 2020). “There is an acute concern happening right now [because] … the eyes of the community are not on our children in the way that they used to be before the state of emergency was called,” said Nicole Bonnie, CEO of the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies. There has been a staggering 40 % reduction in calls to the Children’s Society compared to last year. “With children not being in classrooms, we are certainly seeing a reduction in referrals from schools and school boards” (Haines & Jones, 2020).

3.4.1.4. Colombia

Comparing the periods between March and June of 2019 and 2020, the number of cases reported to the ICBF has considerably dropped. Table 4 indicates the total number of reports and of the reports retained by the ICBF. Based on the data, there was a 21 % decrease in cases reported in 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. Moreover, the cases retained by the ICBF (also decreased by 37 %.

Table 4.

Number of Reports and Cases Retained by the ICBF from March-June 2019/2020.

| Year | # Reports | # Reports retained ICBF (PARD) |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 77.464 | 14.317 |

| 2020 | 61.323 | 9.016 |

Regarding the sources of report (see Table 5 ), civilians continue to be the main source of reporting, presenting a decrease of 15 % in 2020. As expected, due to the lockdown, cases reported by education professionals and early childhood centres decreased by 51 % and 35 %, respectively.

Table 5.

Comparison of Cases Held by the ICBF from March-June 2019/2020, by Source.

| Source | Total 2019 | Total 2020 | Decrease/increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Civilians | 53.372 | 45.114 | −15 % |

| Named civilians | 33.297 | 28.777 | −14 % |

| Anonymous civilians | 20.075 | 16.337 | −19 % |

| Legal Entities/Persons | 16.307 | 10.938 | −33 % |

| Health | 7.612 | 6.072 | −20 % |

| Education | 5.604 | 2.754 | −51 % |

| ICBF | 1.367 | 893 | −35 % |

| NGOs | 805 | 709 | −12 % |

| Legal profesional | 552 | 286 | −48 % |

| Early childhood centers | 299 | 193 | −35 % |

| Protection Institutions | 68 | 31 | −54 % |

| Military / Police Authority | 4.526 | 3.128 | −31 % |

| Judicial Authority | 1.633 | 969 | −41 % |

| Ministries | 905 | 726 | −20 % |

| Administrative Authorities | 720 | 448 | −38 % |

| TOTAL | 77.463 | 61.323 | −21 % |

Source: SIM Missionary Information System ICBF. Consolidated income PARD - cut to June 2020.

In terms of gender, there were 34 % and 40 % less reports retained for girls and boys, respectively (see Table 6 ). In both periods, there were overall more cases reported and retained for girls than for boys.

Table 6.

Number of Reports and Cases Retained by the ICBF from March-June 2019/2020, by Gender.

| Year | Girls # Reports retained (PARD) | Boys # Reports retained (PARD) |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 8.479 | 5.838 |

| 2020 | 5.564 | 3.452 |

Source: SIM Missionary Information System ICBF. Consolidated Income PARD - cut to June 2020.

When presenting the data by children’s age, the number of all cases retained dropped. Nonetheless, note that the cases retained for children between 7 and 12 and between 13 and 18 years old decreased by 41 % and 36 %, respectively (see Table 7 ).

Table 7.

Number of Reports and Cases Retained by the ICBF from March-June 2019/2020, by Age.

| Year | 0−6 Years # Reports retained (PARD) | 7−12 Years # Reports retained (PARD) | 13−18 Years # Reports retained (PARD) | Older than 18 # Reports retained (PARD) | With no age information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2.987 | 4.769 | 6.454 | 79 | 28 |

| 2020 | 2.135 | 2.783 | 4.068 | 18 | 12 |

Source: SIM Missionary Information System ICBF. Consolidated Income PARD - cut to June 2020.

When analysing the data about reasons to retain cases (see Table 8 ), note that cases retained by the ICBF under the category of “no caregiver to care for the child” and “street children” increased by 40 % and 27 %, respectively. Additionally, there were three categories – threat to integrity, caregiver’s especial conditions, and drug abuse – that according to the ICBF were no longer acknowledged in 2020. Even after excluding these categories from the comparison, the overall cases retained by the ICBF in 2020 still decreased by 14 % (instead of the 37 % decrease reported). In any case, these data must be analysed with caution (see Data Reliability).

Table 8.

Comparison of Cases Held by the ICBF from March-June 2019/2020, by Cause.

| Cause | Total 2019 | Total 2020 | Decrease/Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Violence | 4.809 | 3.164 | −34 % |

| Negligence | 2.082 | 1.996 | −4 % |

| No caregivers available | 685 | 1.140 | 40 % |

| Threat to integrity | 1.130 | 0 | N/A |

| Physical violence | 513 | 480 | −6 % |

| Sexual misconduct among children under 14 years | 488 | 259 | −47 % |

| Child labour | 347 | 212 | −39 % |

| Street children/High permanence in street | 301 | 412 | 27 % |

| Abandonment | 289 | 127 | −56 % |

| Psychological violence | 174 | 241 | 28 % |

| Unaccompanied migrant children | 87 | 60 | −31 % |

| Gestation risk | 74 | 61 | −18 % |

| Other | 667 | 861 | 23 % |

| Caregivers special conditions (N/A for 2020) | 1.804 | 2 | N/A |

| Drug abuse (N/A for 2020) | 866 | 1 | N/A |

| TOTAL | 14.317 | 9.016 | −37 % |

Source: SIM Missionary Information System ICBF. Consolidated Income PARD - cut to June 2020.

Regarding the form of reporting (see Table 9 ), the data indicates that during 2020 the reports made by telephone, email, and online increased by 23 %, 23 % and 30 %, respectively. On the other hand, as expected, reports made by on-site and by regular mail decreased by 78 % and 64 %, respectively.

Table 9.

Comparison of Cases Held by the ICBF from March-June 2019/2020, by Medium.

| Medium | # Reports retained 2019 | # Reports retained 2020 | Decrease/Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone | 27.418 | 35.956 | 23 % |

| On site | 22.380 | 4.820 | −78 % |

| 7.480 | 9.749 | 23 % | |

| Paper | 16.798 | 5.969 | −64 % |

| Internet (chat, WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, official website, Instagram) | 3.373 | 4.762 | 30 % |

| Others | 16 | 73 | 78 % |

Source: SIM Missionary Information System ICBF. Consolidated Income PARD - cut to June 2020.

3.4.1.5. Germany

According to a study in which two-thirds of all German Youth Welfare offices participated, there was no increase in reports during the lockdown. At 55 %, the figures are unchanged from the time before the lockdown, at 25 % even lower. Only 5% reported an increase in the number of reports and 15 % do not yet want to make a statement – the figures are dated 17 June. Hospitals report increased numbers of conspicuous injuries, such as broken bones, which may be due to maltreatment, and there are also increased numbers of medical staff using the helpline. Overall, however, there are still no reliable figures.

3.4.1.6. Israel

A dramatic decrease in reports to the CPS occurred in the country, mainly attributed to the closure of schools – the main source of CM reports. Referrals to child advocacy centres decreased by half. However, there are inconsistencies in the data, as with respect to referral to the National Welfare Centre, with reports indicating that although at the beginning of the quarantine there was dramatic decrease in reports, later on there was dramatic increase.

3.4.1.7. South Africa

The lockdown saw an increase in child abuse and abandonment of babies and a 400 % increase in calls to Childline South Africa, of which 62 % were related to child abuse and neglect. At least 30 babies were reportedly abandoned during this period. Anecdotal reports, such as an interview with a regional DSD manager from one province, indicated no increase in reported cases of CM compared to the pre-COVID period. There was however, an increase in parents requesting CPS workers to remove their children as domestic conflict was on the increase as a result of being under lockdown together, and some caregivers struggled to manage this situation Furthermore, in the beginning of the lockdown, it was reported that there were several new problems with regard to care and contact cases, where some children were refused contact with one or the other parent (in cases of divorced or separated families), because of lockdown regulations stipulating that children were not allowed to be moved around (Guest, 2020). Note that separation from the family during pandemics has previously been reported to potentially create “a sense of insecurity in children” (Bakrania et al., 2020, 38), although this problem gradually died out, as South Africa moved to Level 3 Lockdown. A national DSD manager who offered information on behalf of many NGOs in the country anecdotally reported that there was no increase in reports of CM, but this manager ascribed it to the fact that many South Africans did not have airtime or data to report CM. Finally, in the NGO sector, there was an increase, however, in domestic violence when the alcohol ban was lifted on 1 June 2020. According to the NGO sector, accurate data will never be available, a sentiment shared by Idele, Anthony, Damoah, and You (2020).

3.4.2. Child and youth exploitation online

On 2 May, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported that reports to the Australian Centre to Counter Child Exploitation have risen from 776 to 1,731 per month since March, because of children’s additional exposure to the internet (Dillon, 2020).

In Israel, there is an interdisciplinary nationwide centre for online crimes against children in the internet. According to this centre’s report, during COVID-19 there was a significant increase in reports to the centre. The number of reports doubled in April 2020 in comparison to April 2019, with the highest rates of sexual abuse being at the age group of 13. The majority (68 %) of reports were about girls. According to the published data, 33 % of the referrals were from the children themselves, and 30 % were from their parents, with a dramatic decrease in referrals by professionals.

3.5. Additional data: domestic violence, mental health, suicide, and parent helplines

3.5.1. Australia (NSW)

In NSW during the ‘lockdown’ period of March/April 2020 there was a significant reduction in most types of reported crime, followed by an increase after the lockdown period. With regards to domestic violence, the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) concluded:

Among the various measures presented, none show evidence for an increase in domestic violence since the introduction of social distancing and social isolation measures commenced in mid-March 2020. Recorded incidents of domestic violence-related assault and domestic violence-related sexual assault were lower in April 2020 than in April 2019. There were no substantial changes to the most serious forms of domestic violence…. There was also no evidence of a COVID-19 related increase in the number of urgent callouts for police to respond to domestic related incidents or in the number of calls for assistance to the NSW Domestic Violence Line (Freeman, 2020, p7).

With regards to suicide a similar picture has emerged. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported (for the whole of Australia, not just NSW) that there has been a rise in the use of mental health services during the pandemic, but that:

There is thus far no clear evidence of an increase in suicide, self-harm, suicidal behaviour, or suicidal thoughts associated with the pandemic. However, suicide data are challenging to collect in real time and economic effects are evolving. Our LSR will provide a regular synthesis of the most up-to-date research evidence to guide public health and clinical policy to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on suicide (AIHW, 2020).

3.5.2. Canada

During the pandemic, Canada’s Minister for Women and Gender Equality consulted with frontline organizations, provinces, territories and Members of Parliament from across the country to better understand the impact of the crisis on domestic violence. The discussions uncovered a 20 %–30 % increase in rates of gender-based and domestic violence in some regions, though official data were not yet available (Patel, 2020).

Ontario announced that it would be expanding online mental health services, including the national Kids Help Phone line, which has seen a 400 % increase in calls since the pandemic began (Haines & Jones, 2020).

3.5.3. Colombia

Respecting reports on gender violence, the Colombian Women’s Observatory presented an analysis of calls received through Line 155 received between 25 March and 25 June of 2020, comparing to those reported in the same period in 2019. The report showed an increase of 6,415 calls in 2020, or 133 %. The number of calls reporting domestic violence specifically grew by 5,037, or 150 % (Observatorio Mujeres, 2020).

Regarding suicide, the National Institute of Legal and Forensic Medicine compared cases between the January and May of 2020 and 2019, and found a decrease in suicides in 2020 (from 1024 to 917, or 12 %) (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Forense, 2020).

3.5.4. Germany

During the lockdown, there was an increase in helpline requests for counselling.

This indicated an even stronger increase in the demand for online counselling services, as it is more difficult to call for help in the presence of the family. This compares with a known phenomenon in school holidays: "Help phone counsellors know this as the so-called ‘holiday effect’: always after times of ‘prescribed family life’ such as Christmas, the number of children who call and seek help rises sharply” (Jugendhilfeportal, 2020a). Professionals are worried about the actual range of the help, which is now also offered by telephone or virtually, but can then be less trusted (Table 10 ).

Table 10.

Helpline Sessions, Germany.

| Counselling on the child & youth line | Counselling on the parent line | Online Counselling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Febuary 2020 | 7847 | 954 | 976 |

| March 2020 | 8238 (+5,0 %) | 1169 (+22,5 %) | 1047 (+7,3 %) |

| April 2020 | 8700 (+5,6 %) | 1810 (+54,8 %) | 1267 (+21 %) |

https://www.nummergegenkummer.de/neues/anstieg-der-beratungsanfragen.html Published: May 27, 2020.

The help system of child and adolescent psychiatrists was also affected by lack of personnel, the discontinuation of group sessions, and the restriction of face-to-face therapy settings, as well as the general psychological impact of the pandemic-related life situations on the psyche of children and adolescents. Here too, representative data are still missing (Fegert, Berthold, Clemens, & Kölch, 2020).

Domestic violence: “Around 3 percent of women in Germany became victims of physical violence at home during the period of strict contact restrictions. In 6.5 percent of all households, children were punished violently. This is shown by the first large representative survey of the Technical University of Munich (TUM) on domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic” (Jugendhilfeportal, 2020b).

Relatedly, scientists at the University of Fulda speak of the pandemic as a catalyst for child poverty. This is also noticeable with regard to the exclusion from education due to the pandemic (FuldaInfo, 2020).

Children may also be affected by the up to 30 % increase in demand for child pornography in the European Union during the pandemic (ReliefWeb, 2020).

No increase in suicides was reported. Experts pointed out that in many cases, suicides are caused by mental illnesses such as depression, which should be distinguished from situational fears that may arise from the pandemic.

3.5.5. Israel

The Ministry of Welfare reported in the first phase of lockdown an enormous rise (760 %) in domestic violence cases. It also reported a similar rise in cases reported by the dedicated helpline. Interestingly, it seems that while there was a decline in other types of violence (such as against older people), there was a dramatic rise (660 %) in domestic violence and reported violence towards women. The Department of Justice noted a 35 % rise in applications for legal aid concerning domestic violence cases: 37 % of the court orders were against a spouse, 42 % against another family member, and 21 % against others (such as neighbours or colleagues). Finally, a helpline for people with mental distress reported a 500 % rise in calls of youngsters aged 18–20 about domestic violence, and an 80 % rise in children aged 10–13 years calling due to loneliness.

ELEM - Youth in Distress in Israel, an NGO working with youth at risk, reported about their work with some 4800 youth during the first lockdown period (March-May). The report shows that 45 % of the youngsters reported depression, anxiety and other mental health issues; 29 % suffered from loneliness; 23 % abused alcohol and 15 % abused drugs; and 5% attempted suicide. Moreover, homes became unsafe for those youngsters, with 13 % reporting being hungry, 7 % reported being physically and emotionally abused, and 4% reporting being sexually abused (ELEM, 2020).

3.5.6. South Africa

There has been a 37 % increase in gender-based violence-related calls in the first week into lockdown compared to same period in 2019. Police Minister Bheki Cele reported that the police have received more than 87,000 gender-based violence complaints during the first week of the 21-day national lockdown (Mlambo, 2020).

4. Discussion

The aim of the current discussion paper is to generate international exploration of how CM reports and CPS responses have been affected by the COVID-19 crisis in a range of different countries worldwide. Guided by a context inform paradigm, the current discussion paper highlights the importance both for current responses and for future policy development to track how different CPSs have responded to the pandemic as it has affected each system, and then to study the longer term impacts on the systems and ultimately on the CPSs’ capacity to safeguard and protect children in order to learn from each other and improve system responses. This article is therefore intended to initiate this discussion rather than provide a definitive comparison of how different CPSs have responded to COVID-19.

The information available from each country as presented above is highly variable in terms of scope, sources, and issues, and there are significant gaps in the data at this stage. Nevertheless, some important similarities can be seen in the way countries have responded to COVID-19 and the implications of these responses for children. Although the potential risk to children is well demonstrated within the preliminary data, child protection has not been at the forefront of government responses in many jurisdictions. This conclusion is strengthen by additional researchers who pinpoint the way the protection of children had been receiving less attention during the pandemic (Herrenkohl, Scott, Higgins, Klika, & Lonne, 2021), although accumulating knowledge with respect to increase in risk factor for CM (e.g., Rodriguez, Lee, Ward, & Pu, 2021).

Despite the low priority given by policy makers to child protection in some countries, many jurisdictions were able to respond rapidly to the pandemic and to put into place new policies and operating procedures with unprecedented speed. Significant efforts were made by all CPSs in very difficult circumstances to implement processes to protect children, and to ensure the safety of the child protection workforce as well as client families. It would be interesting to examine how these procedures and practice guidelines change as the pandemic progresses and more information is available to policy makers about the nature of COVID-19 and the policy responses and the best ways of mitigating the effects on children and families. There may also be long term impacts on child protection policy and practice, positive and negative, which will require further research.

One objective of this paper was to examine what data were available about CPS responses to COVID-19. Although data were quickly available in the public domain, or at least to researchers in some counties, several countries reported lack of comprehensive and publicly available, up-to-date, and consistent data. For example, in Colombia, the authors found that several figures and indicators changed according to the source, making it difficult to know which to use. The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the urgency of accessing reliable and up-to-date data on child protection services around the world. Without this information, CM would probably not become a top priority for policymakers and its absence may explain the lack of government initiatives to prevent CM during the pandemic. Moreover, greater access to information would contribute immensely to the effectiveness of such initiatives should they be undertaken. Although there have been improvements in data collection and publication in many countries in recent years, the pandemic has highlighted the need for ‘real time’ (or close to real time) publication of data. The NSW DCJ monthly updates are an example of good practice in this area.

Up-to-date data on child protection is limited, but there are indications that, in line with expectations, risk factors related to CM have risen considerably during the pandemic. Many countries reported significant rises in domestic violence reports, including increases in death rates due to domestic and family violence. Those findings are similar to reports of increasing rates of domestic violence surfacing in other countries not included in this discussion. In China, for example, domestic violence is reported to have tripled during their shelter-in-place mandate. Additionally, France indicated a 30 % increase in domestic violence reports; Brazil estimated a 40–50 % increase in domestic violence reports; and Italy also reported an increase (Campbell, 2020). In Spain, reports surfaced of horrific domestic violence (Roca, Melgar, Gairal-Casadó, & Pulido-Rodríguez, 2020).

Thus, it may reasonably expected that CM incidents have also risen considerably. Yet reports of child abuse and neglect have not risen as much as reports of domestic violence in most jurisdictions, and reporting rates even fell in many countries, particularly during periods of plockdown periods. This is confirmed by many child welfare organizations (Campbell, 2020; Martinkevich et al., 2020). This also appears to have been the case in at least some parts of the US. For example, in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, child abuse complaints dropped to five-year lows in April 2020, rising again in June to previous levels (Cleveland.com, 2020). This deduction is strengthened by consistent findings of a rise in CM risk factors during COVID-19, such as parental stress, social isolation and economic hardship (e.g., Bérubé et al., 2020).

One possible explanation for this gap between evident risk to children worldwide and the decrease in CM reports is the closure of schools that was central part of the various countries' restrictions. In ordinary times, schools play a key role in the protection of children, and provide a platform for child wellbeing and safety. This finding reiterates the importance of schools for the protection of children. Moreover, children not only lacked access to school premises, but also had restricted exposure to other adults who would have an opportunity to see them and detect maltreatment, including practitioners in medical and early child education centres.

The decrease in CM reports across the various countries represented herein echoes the core aspects essential to the protecting of children, which must be strengthened during times of worldwide crisis, such as COVID-19. The first is the crucial need for both formal and informal figures to be able to meet the children, ask them about their life during this stressful time and make an initial assessment. Protective adults can be found in the educational system and also within the health system, where they can use their legitimate right to check on people to look after children. Without practitioners who take responsibility for the children and assess the potential of harm to them, the risk to children can be considerably increased.

Placing schools as an active agent in the collective effort can include evidence-based educational actions such as a Spanish initiative to “open doors” at some schools to foster supportive relationships and safe environment to prevent child abuse. This is done through the involvement of teachers in dialogue workspaces, dialogue gathering, etc. (Roca et al., 2020). Teachers need to be trained to identify potential signs of abuse or neglect to children when they are online, and to be supported to respond sensitively and appropriately in reporting their suspicions.

The second aspect is to develop a strategy in which children know to whom they can turn in times of distress, and enabling them to do so during lockdown if they are not safe in their families. CM reports worldwide are systematic in showing that when children disclose intra-familial abuse they usually do so to people outside their families. However, in times of quarantine, these children have few opportunities to speak to trusted adults outside the family, and therefore it is urgent to offer them platforms for "quiet" referral.

The third aspect is public investment in children during the pandemic. As argued above, it appears that in all of the eight countries reviewed here, protecting children from CM was not the top priority for policymakers. However, two significant exceptions show the way forward. Germany provided resources for a public campaign. Canada gave high priority to the protection of children, as indicated in the following quote:

The Quebec government announced Wednesday [1 July] that it will invest $90 million to enhance youth protection in the province. Minister for Health and Social Services Lionel Carmant said that this additional investment will make it possible to consolidate the youth protection service teams, youth accommodation, the Crisis Intervention Program and intensive monitoring in the community as well as those offering legal services (CTV News, 2020).

Fourth, the welfare systems should pay special attention to children who are particularly vulnerable (or included in risk subgroups), including disadvantaged children and children who have experienced childhood adversity and intrafamilial abuse before the pandemic, because they may suffer from accumulative risk and implications (Bryce, 2020). One cohort of children who appear to be particularly at risk during the pandemic are those exposed to family and domestic violence, which has seen a dramatic increase in all countries. It is important that those responding to domestic violence incidents pay close attention to the children in those households, and ensure their safety.

Finally, there is an urgent need for more research, and in particular for countries and child protection systems to learn from each other. The current discussion paper joints to initial efforts in our field. The value of its finding is limited due to gaps in the transparency and consistency of data across countries and the fact that beyond these and methodological challenges, most countries lacked data also due to the fact that the protection of children from maltreatment was not a priority. The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented international crisis, and every country has made mistakes but also achieved some successes. Comparing responses and learning from each other will help each jurisdiction to improve services to protect children affected by the pandemic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the International group of scholars protecting children in COVID-19 which has been an amazing platform for all the contributors of the paper and greatly inspired us in the writing. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- ABS . 2019. 3101.0 - Australian demographic statistics, Jun 2019 Canberra, Australian bureau of statistics.https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/1CD2B1952AFC5E7ACA257298000F2E76?OpenDocument [Google Scholar]

- ACOSS and UNSW . 2018. Inequality in Australia 2018. Sydney, Australian council of social services and UNSW Sydney.https://www.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Inequality-in-Australia-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Adams C. Is a secondary pandemic on its way? Institute of Health Visiting. 2020 https://ihv.org.uk/news-and-views/voices/is-a-secondary-pandemic-on-its-way/ [Google Scholar]

- AIHW . Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2020. The use of mental health services, psychological distress, loneliness, suicide, ambulance attendances and COVID-19.https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- Artz L., Burton P., Ward C., Leoschut L., Phyfer J., Lloyd S.…Le Mottee C. UBS Optimus Foundation; 2016. Sexual victimisation of children in South Africa: Final report of the optimus foundation study.https://www.saferspaces.org.za/resources/entry/sexual-victimisation-of-children-in-south-africa-final-report [Google Scholar]

- 2021. Child protection in the time of COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babvey P., Capela F., Cappa C., Lipizzi C., Petrowski N., Ramirez-Marquez J. Using social media data for assessing children’s exposure to violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;104747 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakrania S., Chavez C., Ipince A., Rocca M., Oliver S., Stansfield O., Subrahmanian R. Office of research – Innocenti working paper. UNICEF; 2020. Impacts of pandemics and epidemics on child protection. Lessons learned from a rapid review in the context of COVID-19.https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/WP-2020-05-Working-Paper-Impacts-Pandemics-Child-Protection.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Baron E.J., Goldstein E.G., Wallace C.T. Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. Journal of Public Economics. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3601399. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bega S., Smillie S., Ajam K. Saturday Start News; 2020. Spike in child abandonments and the physical abuse of youngsters during lockdown.https://www.iol.co.za/saturday-star/news/spike-in-child-abandonments-and-the-physical-abuse-of-youngsters-during-lockdown-48012964 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé A., Clément MÈ, Lafantaisie V., LeBlanc A., Baron M., Picher G.…Lacharité C. How societal responses to COVID-19 could contribute to child neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104761. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33077248; PMCID: PMC7561330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce I. Responding to the accumulation of adverse childhood experiences in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for practice. Children Australia. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1017/cha.2020.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A.M. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas-Bastos Fabricio., H Political Realignment in Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro and the Right Turn. Revista de Estudios Sociales. 2019;69:92–100. doi: 10.7440/res69.2019.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland.com . 2020. Cuyahoga County child-abuse complaints plummeted as the coronavirus kept kids at home.https://www.cleveland.com/news/2020/07/cuyahoga-county-child-abuse-complaints-plummeted-as-the-coronavirus-kept-kids-at-home.html July 31. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia . Commonwealth of Australia, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; Canberra: 2020. Closing the gap report 2020.https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/pdf/closing-the-gap-report-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- CONANDA . 2020. Recomendações do CONANDA para a proteção integral a crianças e adolescentes durante a pandemia do covid-19 [CONANDA recommendations for children and adolescents protection during covid-19 pandemic]http://crianca.mppr.mp.br/arquivos/File/legis/covid19/recomendacoes_conanda_covid19_25032020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- CTV News . 2020. Quebec announces $90 million for youth protection measures.https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/quebec-announces-90-million-for-youth-protection-measures-1.5007110 July 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cuartas J., Grogan-Kaylor A., Ma J., Castillo B. Civil conflict, domestic violence, and poverty as predictors of corporal punishment in Colombia. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2019;90:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DataSenado . 2020. Para a maioria dos brasileiros, a democracia é a melhor forma de governo [Most Brazilians evaluate democracy as the best system of government]https://www12.senado.leg.br/institucional/datasenado/materias/pesquisas/para-a-maioria-dos-brasileiros-a-democracia-e-a-melhor-forma-de-governo [Google Scholar]

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística . 2018. Grupos étnicos - Información técnica.https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/grupos-etnicos/informacion-tecnica [Google Scholar]

- Dillon M. ABC; 2020. Child exploitation websites’ crashing’ during coronavirus amid sharp rise in reported abuse.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-20/afp-concerned-by-child-exploitation-spike-amid-coronavirus/12265544 May 20. [Google Scholar]

- ELEM . 2020. The corona crisis / March-May 2020.https://www.elem.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/ELEM_COVID19_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- e-Safety Commissioner (Australia) 2020. Protecting children from online abuse.https://www.esafety.gov.au/about-us/blog/covid-19-protecting-children-online-abuse [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo-Cely D.M. Grupo de Memoria Histórica, ¡Basta ya! Colombia: Memorias de guerra y dignidad. Historia y Sociedad. 2014;26:274–281. doi: 10.15446/hys.n26.44516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fegert J.M., Berthold O., Clemens V., Kölch M. COVID-19-Pandemie: Kinderschutz ist systemrelevant. Deutsches Aerzteblatt. 2020;117(14) https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/213358/COVID-19-Pandemie-Kinderschutz-ist-systemrelevant A-703 / B-596. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H.-T., Elliott L., Lim Bertrand S. The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action; 2018. Guidance Note on the Protection of children during infectious disease outbreaks.https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/13328/pdf/protection_of_children_during_infectious_disease_outbreak_guidance_note.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Fouché A., Truter E., Fouché F. Safeguarding children in South African townships against child sexual abuse: The voices of our children. Child Abuse Review. 2019;28:455–472. doi: 10.1002/car.2603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman C. NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; Sydney: 2020. Has domestic violence increased in NSW in the wake of COVID-19 social distancing and isolation?https://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Publications/BB/2020-Report-Domestic-Violence-in-the-wake-of-COVID-19-update-to-April20-BB146.pdf Update to April 2020. [Google Scholar]