Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic has resulted in significant negative psychological impacts in our life. Not doing adequate cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nails might be one of the underexplored but preventable reasons for the same.

Aims

To identify the change in cosmetic care habits of female undergraduate medical students during the coronavirus disease pandemic and to identify its psychological impacts on them.

Methods

A total of 218 individuals participated in this online study. Data were collected using a preset pro forma as a Google questionnaire to fulfill the objectives. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 11.5 and presented as percentage, mean, SD, median, IQR in tables and graphs.

Results

Mean age of the participants was 21.56 ± 1.95 years. Maximum respondents (66.0%) are not taking cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail during the pandemic as before. More than two‐thirds (68.8%) are feeling bad, 31.2% are neutral, whereas none are feeling good because of this change. Second‐year students and the participants from rural locations are taking least cosmetic care (p < 0.05). However, coronavirus disease infection and major life events in the family did not affect it. Nail care was prioritized by the maximum (64.2%). Of all participants who are not doing cosmetic care as before, a maximum (50.0%) had lost self‐satisfaction followed by increased irritability (43.8%).

Conclusions

A huge number of female medical students are not doing cosmetic care of their skin, hair, and nail during the coronavirus disease lockdown; they also perceive significant negative psychological impact because of this change.

Keywords: attractiveness, cosmetics, COVID‐19, mental health, skincare, stress

1. BACKGROUND

In sociocultural and cultural‐historical theories, females were often conceptualized in terms of beauty and were often more innovative when it came to their cosmetic needs. Investigations have shown that women use cosmetics for a variety of reasons ranging from feeling less self‐conscious about their appearance, feeling more assertive and confident, or appearing healthier. Everyone would love to look more attractive. Generally, females prefer cosmetics to enhance the feeling of attractiveness. The use of cosmetics also enhances the feeling of youth and femininity. 1 , 2 , 3 It has been reported that people are ready to pay 4 years of the college tuition fee in a year just for their appearance. 4 However, the results are controversial. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9

The year 2020 has been chaotic never like before because of the coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic. Skin health was also affected directly by COVID‐19‐related skin manifestations and indirectly by personal protective equipment‐induced dermatitis. 10 People were at self‐quarantine and working from home because of the lockdown at various parts of the world for a very long duration. So was the situation of all Nepalese including medical students. Due to the quarantine, they might be either unwilling or unable to take cosmetic care of themselves and that can even have negative psychosocial impacts. There are many reasons for negative mental health impacts during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 11 , 12 , 13 Among all, the inability to maintain cosmetic care of self might be another important but unexplored reason. Hence, we tried to find the changes in the cosmetic care routine of skin, hair, and nail during the COVID‐19 lockdown and its psychological impact among the female undergraduate medical students of a university teaching hospital in Nepal.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

An online survey was carried out among female undergraduate medical students using Google form once they voluntarily agreed to participate in the study. The questionnaire was prepared by the subject experts after an extensive literature review to fulfill the objectives of the research. The socio‐demographic profile included age, address, education, stream, current address, number of COVID‐19 confirmed family members, and major life events in the family in the last 6 months (death, birth, major accident, and hospitalization of family members). Contextual matter comprised questions about changes in basic cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail during the COVID‐19 pandemic and psychosocial impact because of the same. Ethical clearance was obtained from the concerned authority, and all ethical issues were taken care of during its execution.

Data were entered in Microsoft Excel and converted into SPSS v11.5 for statistical analysis. For descriptive studies, percentage, ratio, mean, SD, and median were calculated along with the graphical and tabular presentations. For inferential statistics, bivariate analysis was done using the chi‐square test to find out the significant difference between dependent and independent variables. Qualitative variables were categorized and presented as frequencies and percentages. Quantitative variables were presented as the mean and standard deviation. p‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. CASE DEFINITION

Major life events included death, birth, major accident, and hospitalization of family members.

Cosmetic care means cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail which included the use of cosmetics like compact, foundation, beauty salon procedures (eg, facial, threading, bleaching,) lip makeover, eye makeover, hair dyeing, hair styling, and nail procedures like manicure, pedicure, nail painting, nail arts.

4. RESULT

Out of 370 undergraduate female students, 218 participated in our study with a response rate of 58.92%. The mean age of the participants was 21.56 ± 1.95 years with the majority of participants belonging to 21–23 years of age. Out of the 218 participants, 47 (21.6%) belonged to the rural area and 171 (78.4%) to the urban area. Also, 97 (44.5%), 57 (26.1%), and 64 (28.4%) participants were from MBBS, BDS, and B.Sc. Nursing respectively. Forty‐five (20.6%), 31 (14.2%), 62 (28.4%), 80 (36.7%) participants were from first, second, third, and fourth year, respectively. Forty‐two (19.3%) participants had major life events, while the rest 176 (80.7%) had no such events in the past 6 months. Only 10 (4.6%) had confirmed COVID‐19 cases in the family. The majority of the participants (71.1%) had no dermatological problem during quarantine. Among the participants with skin problems (63, 28.9%), only a minority (19.0%) could consult the dermatologist. About one‐third of the participants (34.0%) are taking cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail during the pandemic as before. Students of urban location and students of the third year are taking cosmetic care of the skin, hair, and nail most (p < 0.005). However, COVID‐19 and other major life events in the family did not affect it (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants

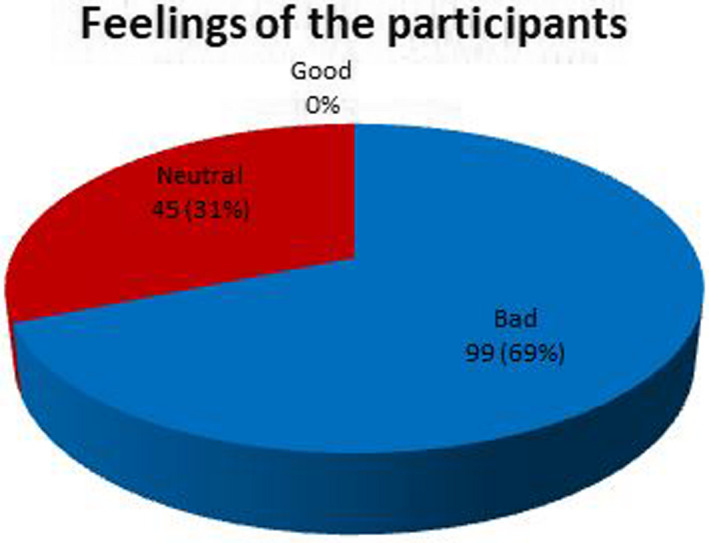

Maximum (69%) participants felt bad for not taking cosmetic care of their skin, hair, and nail as before the COVID‐19 pandemic (p < 0.001). However, none of them felt good about this change (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Feeling of the participants who are not taking cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail as before the COVID‐19 pandemic

Of those who are taking cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail as before, a significant number of the participants (77.0%) are paying attention to nail care. Even among the participants who are not taking cosmetic care as before, a maximum (57.6%) had prioritized nail care (p = 0.005), whereas the least attention was paid to eye cosmetics (p = 0.39) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Trend of cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail among the participants during the COVID pandemic

All participants who are not doing cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail as before the COVID‐19 pandemic perceive that they have some form of negative psychological impact. Maximum participants (50.0%) feel that they have lost self‐satisfaction followed by increased irritability (43.8%) and stress (34.7%), and all parameters are statistically significant (p < 0.001) when compared to those who have not changed their routine (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Perception of the participants who are not doing cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail as before COVID‐19 pandemic (n = 144)

5. DISCUSSION

In our study, only around a third of the participants (34.0%) are taking cosmetic care of their skin, hair, and nail during the pandemic. The third‐year students and those from the urban location were caring for their skin, hair, and nail most. Students are oriented to clinical practice from the third year onwards in our curriculum. Hence, third‐year students might be more conscious of their health, and many procedures like manicure, pedicure, and nail care are directly related to personal hygiene as well.

To our surprise, the presence of COVID‐19 positive cases in the family did not affect it. However, it could be because of fewer participants with positive family history. The majority of the participants (68.8%) who could not take cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail are feeling bad because of these changes. Even among the participants who are not taking care of skin, hair, and nail as before the pandemic, more than half (57.6%) of them are doing nail care. This could be because they might be over‐conscious to maintain hand and nail hygiene during the pandemic. Nail care is primarily involved in hygiene than any fashion symbol. However, most of them (93.8%) are not using eye cosmetics. Likewise, the majority of them (91.7%) are not using facial cosmetics and not doing facial beauty procedures. Similarly, three fourth of them (75.0%) are not doing hair‐related beauty procedures. Exactly similar to our observation, hand hygiene‐related habits have been significantly increased among polish women during the pandemic. Like our participants, significant of them are also not using face and eye cosmetics as before. 14

These days, almost every individual, especially females, uses cosmetics in different forms to enhance their appearance. However, still, lots of controversies exist on the role of cosmetics in beautification. Some reports stand on for and some against. 3 , 5 , 15 , 16 Everyone would love to look beautiful. Everyone wants to have the most fabulous version of self. Most of the females believe that they use cosmetics to look more beautiful and attractive. However, the COVID‐19 pandemic has changed our lives like never before. People were bound to limit themselves behind the closed door because of the lockdown for a longer duration during the pandemic. Many were working from home with limited outdoor activities. Because of various reasons like self‐quarantine, restricted outdoor activities, major life events in the family, closure of beauty parlor and saloon, people might be either unwilling or unable to have cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail. A past report highlighted that makeup has a significant positive role in the perception of competence, likability, and attractiveness of individuals in all societies.

In our study, all participants who are not doing cosmetic care during the pandemic as before feel that they have some form of negative impact on their mental well‐being. Half of them (50.0%) feel that they have lost self‐satisfaction. Some of them (43.8%) had increased irritability, and around a third of them (34.7%) are feeling stressed. However, the change in cosmetic care may not be solely responsible for these negative impacts. The negative psychological impacts due to the COVID‐19 pandemic itself might have contributed significantly and could be an important confounder for these changes. In a systematic review and meta‐analysis, the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression were 29.6%, 31.9%, and 33.7%, respectively, among the general population. 17 A case‐control design would have given a better picture.

However, a significant number of the participants have also perceived that they have lost self‐esteem, self‐confidence, and attention because of change in cosmetic care of skin, hair, and nail. These changes however cannot be explained by the COVID‐19 related negative psychological impacts.

However, a multi‐centered study with a larger sample size, case‐control study design, and specific tools to measure psychological impacts would have given a clearer picture of this topic.

6. CONCLUSION

Whether cosmetics enhance beauty or not has been a matter of debate for since long. However, the finding of our study suggests that it plays an important role in the mental well‐being of females. Individuals might be dissatisfied, irritable, and stressed; likewise, they might also lose confidence, self‐esteem, and attention if they cannot take adequate cosmetic care of themselves. Hence, we suggest the concerned authorities pay attention to this matter, as this is one of the easily rectifiable issues. Encouraging people to continue cosmetic care of themselves during the COVID‐19 surge via different social media might play an important role to improve the mental well‐being of the individual.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from “Departmental Research Unit” of the institute.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to express our deep gratitude to all the participants of this study.

Marahatta S, Singh A, Pyakurel P. Self‐cosmetic care during the COVID‐19 pandemic and its psychological impacts: Facts behind the closed doors. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3094–3098. 10.1111/jocd.14380

REFERENCES

- 1. Korichi R, Pelle‐de‐Queral D, Gazano G, Aubert A. Why women use makeup: implication of psychological traits in makeup functions. J Cosmet Sci. 2008;59(2):127‐137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mileva VR, Jones AL, Russell R, Little AC. Sex differences in the perceived dominance and prestige of women with and without cosmetics. Perception. 2016;45(10):1166‐1183. doi: 10.1177/0301006616652053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Etcoff NL, Stock S, Haley LE, Vickery SA, House DM. Cosmetics as a feature of the extended human phenotype: modulation of the perception of biologically important facial signals. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e25656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mclintock K. The average cost of beauty maintenance could put you through Harvard. Dotdash. https://www.byrdie.com/average‐cost‐of‐beauty‐maintenance#:~:text=Accordingtothestudy%2Cthe,thecourseofalifetime. Published 2020. Accessed January 3, 2021.

- 5. Korichi R, Pelle‐de‐Queral D, Gazano G, Aubert A. Relation between facial morphology, personality and the functions of facial make‐up in women. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2011;33(4):338‐345. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2010.00632.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones AL, Kramer RSS. Facial cosmetics have little effect on attractiveness judgments compared with identity. Perception. 2015;44(1):79‐86. doi: 10.1068/p7904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moradi B, Huang YP. Objectification theory and psychology of women: a decade of advances and future directions. Psychol Women Q. 2008;32(4):377‐398. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Erchull MJ, Liss M. Feminists who flaunt it: exploring the enjoyment of sexualization among young feminist women. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;43(12):2341‐2349. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blake KR, Brooks R, Arthur LC, Denson TF. In the context of romantic attraction, beautification can increase assertiveness in women. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):1‐19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Akl J, El‐Kehdy J, Salloum A, Benedetto A, Karam P. Skin disorders associated with the COVID‐19 pandemic: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3105‐3115. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Panchal N, Kamal R, Cox C, Rachel G. The Implications of COVID‐19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. KAISER HEALTH NEWS. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus‐covid‐19/issue‐brief/the‐implications‐of‐covid‐19‐for‐mental‐health‐and‐substance‐use/. Accessed May 19, 2021.

- 12. Javed B, Sarwer A, Soto EB, Mashwani ZR. The coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic's impact on mental health. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2020;35(5):993‐996. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khademian F, Delavari S, Koohjani Z, Khademian Z. An investigation of depression, anxiety, and stress and its relating factors during COVID‐19 pandemic in Iran. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1‐7. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10329-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mościcka P, Chróst N, Terlikowski R, Przylipiak M, Wołosik K, Przylipiak A. Hygienic and cosmetic care habits in polish women during COVID‐19 pandemic. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19(8):1840‐1845. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones AL, Kramer RSS, Ward R. Miscalibrations in judgements of attractiveness with cosmetics. Q J Exp Psychol. 2014;67(10):2060‐2068. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2014.908932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palumbo R, Fairfield B, Mammarella N, Di Domenico A. Does make‐up make you feel smarter? The “lipstick effect” extended to academic achievement. Cogent Psychol. 2017;4(1):1‐9. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2017.1327635 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salari N, Hosseinian‐Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Global Health. 2020;16(1):1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]