During the COVID‐19 pandemic, many Japanese university students have been facing harsh living conditions. For example, instead of face‐to‐face sessions, many classes have been conducted remotely and students have had fewer opportunities to communicate with their friends, as a result of which they have often felt isolated. Many of them have suffered financial distress because of the pandemic‐induced reduction in their parents' income, and the additional difficulty of having to find part‐time jobs to cover their tuition and living expenses. In addition, 4th‐year students have had to address the challenge of job hunting in the face of a slowdown in employment activity. Furthermore, the pandemic has persisted much longer than they had first expected, and this has led some of them to have less hope. Under these circumstances, student mental health problems, including, in some cases, having suicidal thoughts, have been of particular concern.

On behalf of the Mental Health Committee of the Japanese National University Council of Health Administration Facilities, we have organized a continuous survey titled ‘The survey of undergraduate students who require temporary leave from school, drop out of school, or repeat the same class.’1, 2 We conducted part of the survey earlier than usual to see whether the suicide rate in the academic year 2020–2021 was higher than those in past years or not.

We requested health administration facilities at all 82 national universities with undergraduate schools in Japan to participate in the survey. Along with the total number of registered undergraduate students on 1 May 2020, we asked them to provide detailed information, including the sex and cause of death of each student who died in the academic year 2020–2021 (from 1 April 2020, to 31 March 2021). This study was approved by The Ethics Review Committee of the Japanese National University Council of Health Administration Facilities (N.3) and that of Ibaraki University (N. 150600).

All 82 universities participated in the survey and the number of registered students was 433 032 (273 308 men and 159 724 women). It was determined that 76 students (58 men and 18 women) died of suicide or suspected suicide as the cause of death. The suicide rates (per 100 000 students) were 17.6 in total, 21.2 for men, and 11.3 for women.

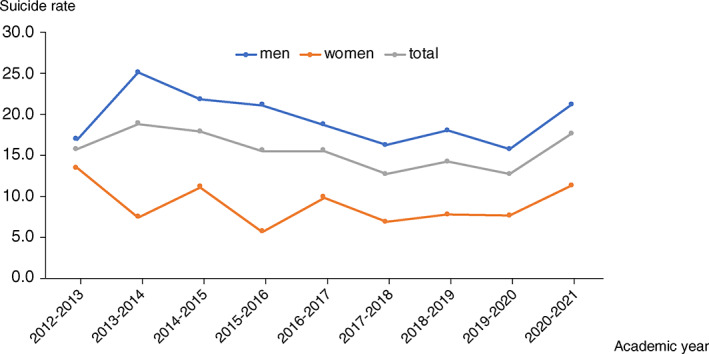

Figure 1 shows the annual tendency of suicide rates among undergraduate students from the academic years 2012–2013 to 2020–2021 extracted from our past surveys 1 wherein about 70 universities participated each year. The suicide rates in total, and for men in the academic year 2020–2021 was the highest in the last six academic years, and that for women was the highest in the last 8 years.

Fig 1.

The annual tendency of suicide rates (per 100 000 students) among undergraduate students from the academic years 2012–2013 to 2020–2021 was extracted from our past surveys. 2 The suicide rates in total and for men in the academic year 2020–2021 was the highest in the last six academic years, and that for women was the highest in the last 8 years.

Our continuous suicide rate survey is precise because it has been conducted every year. Thus, we can observe the annual transition of the suicide rates. Furthermore, all national universities with undergraduate schools participated in it on the academic year 2020–2021.

Tanaka and Okamoto reported the increasing trend of suicide rate following an initial decline during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Japan, with larger increase among female, 3 and according to the official report, the total suicide rate among the Japanese general population increased in 2020 for the first time in the last 12 years, and that of women increased for the first time in the last 2 years. 4 We found that an increase in the suicide rate was seen not only among the general population, but also among undergraduate students. An alarming proportion of university students reportedly presented with depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts in various countries in 2020.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 The present results that the suicide rate among undergraduate students in Japanese national universities has increased reflects that Japan was no exception. Suicide prevention measures for university students are an urgent requirement. As the next step of our study, we should analyze the attributes of the students who died of suicide or suspected suicide in the academic year 2020–2021 and compare them with the results of our past study. It would lead us to find the characteristics of the high‐risk population under the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Limitations

No statistical analysis was made to prove the increasing trend of suicide rate. We obtained data on the cause of death collected by the health administration facilities and the student affairs divisions. They are mostly accurate, but we admit that there might be underreporting of the number of suicides.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the health administration facilities and the student affairs divisions of all national universities that participated in this survey.

References

- 1. Fuse‐Nagase Y, Kajitani K, Hirai N, Namura I, Sato T. The survey of undergraduate students who require temporary leave from school, drop out of school, or repeat the same class–results of the academic year 2017–2018. Jpn. J. Coll. Mental Health. 2021; 4: 47–59 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marutani T, Yasumi K, Takayama J, Saito K, Sato T. The survey of graduate students who require temporary leave from school, drop out of school, or repeat the same class–results of the academic year 2017–2018. Jpn. J. Coll. Mental Health. 2021; 4: 60–70 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tanaka T, Okamoto S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Japan. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2121; 5: 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suicide Countermeasures Promotion Office, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and Life Safety Bureau Life Safety Planning Division, National Police Agency Suicide situation in 2020. [Cited 01 July 2021.] Available from URL: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/R2kakutei-01.pdf (in Japanese).

- 5. Wang X, Hegde S, Son C, Keller B, Smith A, Sasangohar F. Investigating mental health of US College students during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Cross‐sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020; 22: e22817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Batra K, Sharma M, Batra R, Singh TP, Schvaneveldt N. Assessing the psychological impact of COVID‐19 among college students: An evidence of 15 countries. Healthcare (Basel) 2021; 9: 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kohls E, Baldofski S, Moeller R, Klemm SL, Rummel‐Kluge C. Mental health, social and emotional well‐being, and perceived burdens of university students during COVID‐19 pandemic lockdown in Germany. Front. Psych. 2021; 12. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wathelet M, Duhem S, Vaiva G et al. Factors associated with mental health disorders among university students in France confined during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020; 3: e2025591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kassir G, El Hayek S, Zalzale H, Orsolini L, Bizri M. Psychological distress experienced by self‐quarantined undergraduate university students in Lebanon during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2021; 25: 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. López Steinmetz LC, Leyes CA, Dutto Florio MA, Fong SB, López Steinmetz RL, Godoy JC. Mental health impacts in Argentinean college students during COVID‐19 quarantine. Front. Psych. 2021; 12. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.557880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]