Abstract

The Staphylococcus aureus aroA gene, which encodes 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase, was used as a target for the amplification of a 1,153-bp DNA fragment by PCR with a pair of primers of 24 and 19 nucleotides. The PCR products, which were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis, were amplified from all S. aureus strains so far analyzed (reference strains and isolates from cows and sheep with mastitis, as well as 59 isolates from humans involved in four confirmed outbreaks). Hybridization with an internal 536-bp DNA fragment probe was positive for all PCR-positive samples. No PCR products were amplified when other Staphylococcus spp. or genera were analyzed by using the same pair of primers. The detection limit for S. aureus cells was 20 CFU when the cells were suspended in saline; however, the sensitivity of the PCR was lower (5 × 102 CFU) when S. aureus cells were suspended in sterilized whole milk. TaqI digestion of the PCR-generated products rendered two different restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns with the cow and sheep strains tested, and these patterns corresponded to the two different patterns obtained by antibiotic susceptibility tests. Analysis of the 59 human isolates by our easy and rapid protocol rendered results similar to those of other assays.

Staphylococcus aureus is the causative agent of many opportunistic infections in humans and animals (8). As a human pathogen, S. aureus causes superficial, deep-skin, and soft-tissue infections, endocarditis, and bacteremia, as well as a variety of toxin-mediated diseases including gastroenteritis, staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome, and toxic shock syndrome (6, 19). Among animals, from whose milk it is frequently isolated, it is the leading cause of intramammary infections in cows, with major economic repercussions (1, 24). An outbreak on a farm is often caused by a single strain and may lead to further outbreaks among the same species in the same region. In such cases, it is of crucial importance to isolate and identify the offending strain in order for appropriate antibiotic therapy to be initiated. Several methods of identification of S. aureus have been proposed, including those that detect traditional phenotypic properties, and in recent years these methods have been available in miniaturized form for automation and convenience (2, 23). Molecular methods such as PCR-based DNA fingerprinting or hybridization have also successfully been used for S. aureus identification and typing (5, 7, 9, 13, 17, 21, 22).

In general, rapid bacterial identification by either PCR or hybridization uses species-specific and ubiquitous DNA as a target (3, 13). However, the use of universal pathway genes and universal function genes, whose nucleotide sequences are fairly homologous among bacteria, as target DNAs for PCR amplification is becoming more and more frequent. Gho et al. (7) recently presented data suggesting that a universal DNA target, the chaperoning 60 gene, may be useful for Staphylococcus species identification. The aroA gene, which encodes 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (a key enzyme of aromatic amino acids and the folate universal biosynthetic pathway) of Aeromonas hydrophila, was used as a target DNA to identify most species of Aeromonas genus by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis-PCR (4). Also, Mollet et al. (15) were able to assign 20 selected clinical isolates to the correct enteric species on the basis of RNA polymerase β-subunit gene (rpoB) sequence comparison after PCR amplification. The presence of alternating stable and variable regions within bacterial rpoB genes allowed them to design primers within stable regions flanking the sequence encoding a variable polypeptide region and may be used as a good tool for the identification of enterobacteria.

In this paper we describe a rapid, sensitive, and specific nucleic acid-based procedure that permits the identification of S. aureus in cows and sheep with intramammary infections by PCR amplification of the aroA gene. The procedure is further enhanced when it is combined with RFLP analysis, which allows discrimination among S. aureus isolates. We have also used our protocol to characterize 59 S. aureus isolates previously characterized by others (20, 22). When compared with other methods, our method had an intermediate degree of discriminatory power, 100% typeability, and 100% reproducibility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The S. aureus strains used in this study were isolated from milk from both cows (38 strains) and ewes (6 strains) with acute clinical mastitis. All of the animals came from farms in northwest Spain, and the farms belonged to health protection associations under veterinary surveillance. Animals from a total of 30 farms were analyzed, with from 30 to 50 animals from each farm being analyzed, but animals on only 10 of the farms were positive for S. aureus. The number of isolates from each farm ranged from 1 to 10. The 59 S. aureus isolates from humans were obtained from individuals involved in four confirmed outbreaks, named outbreaks I, II, III, and IV, and one pseudo-outbreak, and were grouped as in previous studies in groups of 20 (designated groups SA, SB, and SC) including Internal controls, which were either duplicates of the same isolate or isolates obtained from the same patient, were included in each group. S. aureus ATCC 12600 was included in all groups (strains SA4, SB7, and SC3), while a single strain of S. intermedius (ATCC 49052) was included in the SA group (strain SA16). The 59 S. aureus isolates were made available through F. C. Tenover (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.) (20, 22). The reference Staphylococcus strains used in this study were selected from the Spanish Type Culture Collection (CECT) and were as follows: S. aureus CECT 86 (ATCC 12600), S. xylosus CECT 237, S. hominis CECT 234, S. saprophyticum CECT 235, S. epidermidis CECT 232, S. warneri CECT 236, S. capitis CECT 233, S. simulans CECT 4538, S. auricularis CECT 4052, and S. carnosus CECT 4491. Other reference Staphylococcus strains were S. hyicus ATCC 11249, S. delphini ATCC 49171, and S. lugdenensis ATCC 43809. Strains were grown on Luria agar or Luria broth (LB) and manitol salt agar. Escherichia coli C600, Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966, Pseudomonas putida, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Sarcina lutea, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptomyces griseus were used as negative controls in the PCR assays, and all isolates except A. pleuropneumoniae were grown on LB. A. pleuropneumoniae was grown on brain heart infusion agar supplemented with 0.1% NAD. All cells except those of S. griseus and A. hydrophila were incubated at 37°C; S. griseus and A. hydrophila cells were grown at 28°C.

Identification and susceptibility testing.

Isolates were identified as S. aureus on the basis of colony morphology, Gram staining result, the presence of catalase-positive cocci in clumps, and the detection of coagulase production with fresh rabbit plasma (with a colony obtained from an overnight culture suspended in 0.5 ml of plasma and incubated at 37°C for 2 h) and by using a commercial identification system (API Staph; Biomerieux). All isolates were tested for their susceptibilities to different antibiotics by the disk agar method as standardized by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (16). The following antimicrobial disks were used at the indicated concentrations: penicillin, 10 U; ampicillin, 10 μg; amoxicillin-clavulanate, 20 and 10 μg, respectively; oxacillin, 1 μg; cloxacillin, 1 μg; erythromycin, 15 μg; oxytetracycline, 30 μg; and gentamicin, 10 μg (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). S. aureus CECT 435 was used as a control. The results were recorded after 24 h of incubation at 35°C.

Chromosomal DNA isolation and manipulation.

Chromosomal DNAs from E. coli, A. hydrophila, P. putida, A. pleuropneumoniae, S. lutea, B. subtilis, and S. griseus were obtained from overnight cultures grown in LB agar or brain heart infusion agar supplemented with NAD as indicated above. Samples to be analyzed (a colony) were suspended in 100 μl of 1× PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 2 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl) and were incubated at 95°C for 15 min. A total of 1 μl of the samples was used for PCR analysis. Chromosomal DNAs from the Staphylococcus strains were extracted by the following protocol. A colony of Staphylococcus or 1 μl containing from 103 to 105 CFU was suspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl, 0.5% [vol/vol] Tween 20, 0.45% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40, 0.01% [wt/vol] gelatin, and 60 μg of proteinase K per ml), and the mixture was incubated at 55°C for 1 h. The samples were then incubated at 95°C for 10 min. A total of 5 μl of each sample was used for PCR analysis. Chromosomal DNA was also obtained directly from milk, once S. aureus had been detected in the sample, by adding 100 μl of milk to 100 μl of 2× lysis buffer and testing the sample by the protocol mentioned above.

Blotting and hybridization were performed by standard procedures, and DNA labeling was carried out by random priming with digoxigenin-dUTP. Hybrids were detected by enzyme immunoassay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). For digestion of the PCR products, a 5-μl sample was used. Restriction endonucleases were purchased from Boehringer GmbH.

PCR-RFLP assays.

PCR amplification tests were performed with a pair of primers selected on the basis of the published nucleotide sequence of the S. aureus aroA gene (length, 1,283 bp; GenBank database accession no. L05004). A 24-nucleotide forward primer, FA1 (5′-AAGGGCGAAATAGAAGTGCCGGGC-3′), corresponding to positions 40 to 63, and a 19-nucleotide reverse primer, RA2 (5′-CACAAGCAACTGCAAGCAT-3′), corresponding to positions 1192 to 1174, were selected. The primers were synthesized by British Bio-Technological Products (Avingdon, England). PCR amplification was carried out with a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) by using a PCR kit (Boehringer GmbH) and by following the instructions of the manufacturer, with some modifications. Briefly, the reaction mixture consisted of 5 μl of a sample containing DNA, 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 5 μl of 10× PCR amplification buffer, 0.6 μM each primer, 0.5 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and double-distilled water to a final volume of 50 μl. To minimize evaporation, 50 μl of mineral oil was added to the mixture. DNA was denatured at 94°C for 2 min. A total of 40 PCR cycles were run under the following conditions: DNA denaturation at 92°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 58°C for 1 min, and DNA extension at 72°C for 1.5 min. After the final cycle, the reactions were terminated by an extra run at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (with 3% agarose gels run in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer). The RFLP procedure was carried out by digesting the PCR-amplified products with either TaqI or RsaI endonucleases, and the products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis as described above. For determination of the sensitivity of the PCR, 10-fold serial dilutions (106 to 0 bacteria) in both saline and sterilized whole milk were tested. One hundred microliters of each dilution was processed as described above, and 5 μl of each sample was used for PCR amplification. The numbers of viable cells were counted by determining the numbers of CFU by triplicate plating of the samples on Luria agar and counting of the colonies after incubation at 37°C for 24 h. When nucleic acids were used, the sensitivity of the PCR was determined by amplifying 5 μl of 10-fold serial dilutions (1 ng to 0.1 pg).

RESULTS

Phenotypic characteristics of S. aureus isolates.

All isolates were gram-positive cocci and coagulase positive and were identified as S. aureus as described in Materials and Methods. Antibiotic sensitivity testing (Table 1) showed two patterns. The isolates with one of the patterns, designated group 1, were represented by eight S. aureus isolates (two from cows and six from ewes) which were sensitive to penicillin G, ampicillin, and amoxicillin-clavulanate. However, the isolates with the second pattern, designated group 2, represented by 36 isolates, originated from 36 samples collected from cows, and the isolates were resistant to the same three antibiotics. Very similar patterns of susceptibility to five other antibiotics were observed for all S. aureus isolates, with sensitivity to oxacillin, erythromycin, and oxytetracycline, resistance to cloxacillin, and an intermediate response to gentamicin. Two isolates from group 2 were resistant to erythromycin and one was resistant to oxytetracycline. The susceptibility pattern of the reference strain, S. aureus CECT 86, was identical to those of the group 1 isolates.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities of S. aureus isolates to different antibiotics and RFLP patterns

| Antibiotic | Susceptibilitya

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus group 1 (8 isolates) | S. aureus CECT 86 (ATCC 12600) | S. aureus group 2 (36 isolates) | |

| Penicillin G | S | S | R |

| Ampicillin | S | S | R |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | S | S | R |

| Oxacillin | S | S | S |

| Cloxacillin | R | R | R |

| Erythromycin | S | S | Sb |

| Oxytetracycline | S | S | Sc |

| Gentamicin | I | I | I |

S, sensitive; R, resistant; I, intermediate. The S. aureus group 1 isolates and S. aureus CECT 86 had RFLP pattern 1, and S. aureus group 2 isolates had RFLP pattern 2.

Two isolates were resistant.

One isolate was resistant.

PCR-RFLP analysis.

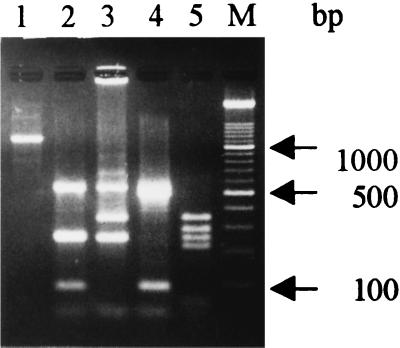

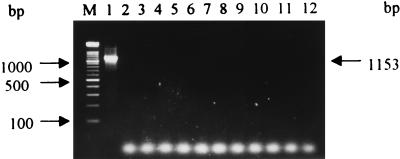

The pair of primers used in this study, FA1 and RA2, from the S. aureus aroA gene, successfully primed the synthesis of an expected 1,153-bp fragment which represents most of the aroA gene sequence (Fig. 1, lane 1) of all isolates and strains of S. aureus tested. No PCR amplification products were obtained when other Staphylococcus spp. or genera were used as sources of high-molecular-weight target DNA (Fig. 2). Also, a single 1,153-bp band was obtained when the PCR products hybridized with the internal 536-bp TaqI fragment of the aroA gene which was cloned from the S. aureus CECT 86 PCR-amplified product and digested with TaqI endonuclease (data not shown). These results demonstrate that PCR amplification of the aroA gene could be a useful tool for the rapid identification of S. aureus DNA not only from bacterial cells but also from biological materials, such as milk. The sensitivity of our PCR assay was 20 viable S. aureus cells or 40 pg of extracted DNA; however, when S. aureus was serially diluted in sterilized whole milk, the lower detection limit was about 500 CFU.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR amplification products from high-molecular-weight chromosomal DNA from S. aureus and fragments produced by TaqI endonuclease digestion. Lanes: 1, 1,153-bp PCR amplification product; 2, RFLP patterns 1 and A; 3, RFLP patterns 2 and B; 4, RFLP pattern C; 5, RFLP pattern D; M, DNA molecular mass marker (100-bp ladder; bottom band, 100 bp).

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR amplification products from S. aureus chromosomal DNA and other Staphylococcus spp. and genera used as negative controls. Lanes: 1, 1,153-bp PCR amplification product from S. aureus CECT 86; 2, E. coli; 3, S. intermedius; 4, S. epidermidis; 5, S. xylosus; 6, S. hominis; 7, S. delphini; 8, A. hydrophila; 9, B. subtilis; 10, P. putida; 11, S. lutea; 12, A. pleuropneumoniae; M, DNA molecular mass marker (100-bp ladder; bottom band, 100 bp).

PCR products of all S. aureus isolates were digested with TaqI, and the resulting fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Two distinct RFLP patterns were observed (Fig. 1) among the 44 isolates. One of them, RFLP pattern 1, represented by reference strain CECT 86, two isolates from cows, and six isolates from sheep, rendered five bands of 536, 254, 244, 87, and 32 bp after TaqI digestion (Fig. 1, lane 2). The other one, RFLP pattern 2, was represented by the 36 group 2 isolates from cows. As shown in Fig. 1 (lane 3), four fragments of 536, 341, 244, and 32 bp were generated after digestion with TaqI endonuclease. A good correlation between the results of testing of susceptibility to antibiotics and the results of genotyping were found. All isolates with RFLP pattern 1 were sensitive to penicillin G, ampicillin, and amoxicillin-clavulanate, although the isolates with RFLP pattern 2 were resistant to these three antibiotics.

Characterization of 59 S. aureus isolates by PCR-RFLP analysis.

The 59 S. aureus isolates from humans and S. intermedius ATCC 49052 (strain SA16) were analyzed by our PCR protocol described above. A 1,153-bp fragment, which represents most of the S. aureus aroA sequence, was amplified from all 59 isolates, as expected (Fig. 1, lane 1). The pair of primers used, FA1 and RA2, did not prime the synthesis of the expected PCR product when S. intermedius ATCC 49052 cells were used as the source of target DNA (Fig. 2, lane 3). When the 1,153-bp PCR product was digested with TaqI endonuclease, four RFLP patterns, RFLP patterns A, B, C, and D, were obtained.

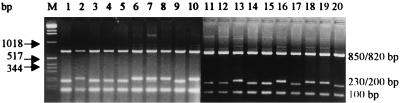

RFLP pattern A (Fig. 1, lane 2; Table 2), which was identical to RFLP pattern 1 (see above), included 23 isolates comprising the complete SC group of strains and strains SA4, SB7 (S. aureus ATCC 12600), and SB8, an isolate with no clear epidemiological link to the other isolates in the SB group. Our fingerprinting protocol was not very discriminatory because the SC group contained isolates from two relatively well-defined outbreaks, as well as an unrelated control strain (strain SC8) and S. aureus ATCC 12600 (strain SC3). However, the 23 isolates with RFLP pattern A were split into two RFLP patterns, RFLP pattern A1 and RFLP pattern A2, after digestion of the 1,153-bp PCR product with RsaI (Fig. 3), which clearly separated the isolates included in each of the well-defined outbreaks III and IV.

TABLE 2.

RFLP patterns of SA, SB, and SC groups of S. aureus isolates from humans after digestion of PCR products with TaqI or RsaI

| Isolates with the following RFLP pattern:

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | A1b | A2b | Ba | Ca | Da |

| SA4 | SA4 | SC2 | SA14 | SA8 | SA1 |

| SB7 | SB7 | SC6 | SB2 | SA11 | SA2 |

| SB8 | SB8 | SC7 | SB4 | SA3 | |

| SC1 | SC1 | SC8 | SB6 | SA5 | |

| SC2 | SC3 | SC10 | SB9 | SA6 | |

| SC3 | SC4 | SC13 | SB11 | SA7 | |

| SC4 | SC5 | SC16 | SB13 | SA9 | |

| SC5 | SC9 | SC18 | SB17 | SA10 | |

| SC6 | SC11 | SC19 | SA12 | ||

| SC7 | SC12 | SA13 | |||

| SC8 | SC14 | SA15 | |||

| SC9 | SC15 | SA17 | |||

| SC10 | SC17 | SA18 | |||

| SC11 | SC20 | SA19 | |||

| SC12 | SA20 | ||||

| SC13 | SB1 | ||||

| SC14 | SB3 | ||||

| SC15 | SB5 | ||||

| SC16 | SB10 | ||||

| SC17 | SB12 | ||||

| SC18 | SB14 | ||||

| SC19 | SB15 | ||||

| SC20 | SB16 | ||||

| SB18 | |||||

| SB19 | |||||

| SB20 | |||||

RFLP patterns obtained by TaqI digestion of PCR products.

RFLP patterns obtained by RsaI digestion of PCR products.

FIG. 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of fragments produced by RsaI digestion of the 1,153-bp PCR amplification products from S. aureus SC group. Lanes 1 to 20, strains SC1 to SC20, respectively; lane M, molecular mass marker (from top to bottom, 12,216 to 75 bp).

RFLP pattern B, which was identical to RFLP pattern 2 (see above), was generated by TaqI digestion of the 1,153-bp fragment PCR product for eight isolates (Fig. 1, lane 3; Table 2), including all isolates from outbreak II (isolates SB2, SB4, SB6, and SB11), three epidemiologically unrelated isolates within set B (isolates SB9, SB13, and SB17), and isolate SA14.

RFLP pattern C was generated by TaqI digestion of the 1,152-bp fragment PCR product for isolates SA8 and SA11 (Fig. 1, lane 4; Table 2), which rendered four fragments of 536, 499, 87, and 32 bp. These two isolates and isolate SC8 had identical fingerprints when they were analyzed previously (20).

RFLP pattern D (Fig. 1, lane 5; Table 2) had five bands of 341, 300, 244, 220, and 50 bp after TaqI digestion of the previously mentioned 1,153-bp fragment for 26 isolates included in sets SA and SB; all of these isolates have identical fingerprints according to Smeltzer et al. (20). In general, our fingerprinting protocol was easily able to group the 59 S. aureus isolates from humans and was able to do so with a reasonable discriminatory power.

DISCUSSION

The use of nucleic acid amplification by PCR has applications in many fields, especially for the rapid identification of bacteria. In this study we were able to identify S. aureus strains isolated from cows and sheep with clinical mastitis by PCR amplification of the aroA gene. The pair of primers used in this study did not recognize the other bacteria tested. The aroA gene has previously been used with success as a tool for examination of the taxonomy of Aeromonas genus, a gram-negative bacterium (4). The sensitivity of PCR analysis for S. aureus accords with that described for other bacteria, that is, between 1 and 20 CFU or between 1 and 100 pg for DNA extracted from S. aureus (3, 4, 11, 18).

On the basis of the published nucleotide sequence of the aroA gene from S. aureus (GenBank accession no. L05004), we analyzed this gene by means of a computer program (RESTRI, PC-GENE) to carry out RFLP analysis. Good results were obtained when PCR-amplified DNAs from all S. aureus isolates were digested with TaqI endonuclease. For all S. aureus isolates from cows and sheep, a good relationship between antibiotic susceptibility type and RFLP pattern after TaqI endonuclease digestion was found. Most isolates from cows (36 of 38) had identical antibiotic susceptibility types and RFLP patterns; however, 2 isolates from cows, 6 isolates from sheep, and the reference strain, S. aureus CECT 86, had quite different RFLP patterns and antibiotic susceptibilities. The two patterns found for isolates of S. aureus from animals were in contrast to those found for isolates from humans, for which a high degree of diversity has been found (20). The results of this analysis may be limited for an epidemiological study, although our data support those found by others with isolates from cows, in which only a small number of S. aureus genotypes were isolated from cows with clinical mastitis (14, 10, 12). Three possible explanations were given. The first and most likely explanation was that a small number of different genotypes of S. aureus in cows with mastitis may be due to contagion of the pathogen among the animals on a farm. Second, perhaps only a small number of strains have enough virulence to cause mastitis. The third explanation was that not all different S. aureus strains can be adequately differentiated by currently available methods.

Our PCR-RFLP protocol was also used to characterize 59 S. aureus isolates which had previously been analyzed by other fingerprinting protocols (20, 22), including reference strains, isolates from four well-defined outbreaks, and unrelated strains. Our results indicate that the PCR-RFLP protocol used is relatively accurate with regard to the identification of epidemiologically related isolates, but it tends to include unrelated strains falsely within epidemiologically related groups. As suggested by Tenover et al. (22), the correct epidemiological typing of S. aureus might require a combination of methods. Initially, the analysis could be performed by a simple method that is able to identify all potentially related strains, after which a second method capable of discriminating among individual isolates could be applied. Our PCR protocol is one of the best alternatives for the former, because we have clearly demonstrated that PCR amplification of the aroA gene is specific for S. aureus identification and is further enhanced when it is combined with RFLP analysis, which allows a reasonable discrimination among strains and isolates, while it can be performed quickly and easily.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Laboratorio Pecuario Regional (León, Spain) for providing us with valuable material for this study and Fred C. Tenover for providing us strains of S. aureus.

This work was supported by a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (grant DGICYT PB94-0136). J.Y.M. is the holder of a fellowship from the University of León.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartlett P C, Miller G Y, Lancet S E, Heider L E. Clinical mastitis and intramammary infections on Ohio dairy farms. Prev Vet Med. 1992;12:59–71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bes M, Brun Y, Gayral J P, Fleurette J, Laban P. Improvement of the API Staph gallery and identification of new species of staphylococci. Zentralbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektionskr Hyg Abt 1 Orig. 1985;14:169–171. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cascón A, Anguita J, Hernanz C, Sánchez M, Fernández M, Naharro G. Identification of Aeromonas hydrophila hybridization group 1 by PCR assays. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1167–1170. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1167-1170.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cascón A, Anguita J, Hernanz C, Sánchez M, Yugueros J, Naharro G. RFLP-PCR analysis of the aroA gene as a taxonomic tool for the genus Aeromonas. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;156:199–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuny C, Witte W. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus by PCR for DNA sequences flanked by Tn916 target region and ribosomal binding site. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1502–1505. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1502-1505.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fidalgo S, Vasques F, Mendoza M C, Pérez F, Méndez F J. Bacteremia due to Staphylococcus epidermidis: microbiological, epidemiologic, clinical, and prognostic features. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:520–528. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goh S H, Santucci Z, Kloos W E, Faltyn M, George C G, Driedger D, Hemmingsen S M. Identification of Staphylococcus species and subspecies by the chaperoning 60 gene identification method and reverse checkerboard hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3116–3121. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3116-3121.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kools W E, Bannerman T L. Staphylococcus and Micrococcus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 282–298. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumari D N P, Keer V, Hawkey P M, Parnell P, Joseph N, Richardson J F, Cookson B. Comparison and application of ribosome spacer DNA amplicon polymorphisms and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for differentiation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:881–885. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.881-885.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam T J G M, Lipman L J A, Schukken Y H, Gaastra W, Brand A. Epidemiological characteristics of bovine clinical mastitis caused by Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus studied by fingerprinting. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lebech A M, Hindersson P, Vuust J, Hansen K. Comparison of in vitro culture and polymerase chain reaction for detection of Borrelia burgdorferi in tissue from experimentally infected animals. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:731–737. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.4.731-737.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipman L A J, De-Nijs A, Lam T J G M, Rost J A, Van-Dijk L, Schukken Y H, Gaastra W. Genotyping by PCR, of Staphylococcus aureus strains, isolated from mammary glands of cows. Vet Microbiol. 1996;48:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martineau F, Picard F J, Roy P H, Oullette M, Bergeron M G. Species-specific and ubiquitous-DNA based assays for rapid identification of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:618–623. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.618-623.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews K R, Kumar S J, O’Conner S A, Harmon R J, Pankey J W, Fox L K, Oliver S P. Genomic fingerprints of Staphylococcus aureus of bovine origin by polymerase chain reaction-based DNA fingerprinting. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:177–186. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005754x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mollet C, Drancourt M, Raoult D. rpoB sequence analysis as a novel basis for bacterial identification. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:1005–1011. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6382009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Approved standard M2-A5. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. 5th ed. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Na’was T, Hawwari A, Hendrix E, Hebden J, Edelman R, Martin M, Campbel W, Naso R, Schwalbe R, Fattom A I. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus isolates from trauma patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:414–420. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.414-420.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olive D M. Detection of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli after polymerase chain reaction amplification with a thermostable DNA polymerase. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:261–265. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.261-265.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts F J, Gere I W, Coldman A. A three-year study of positive blood cultures, with emphasis on prognosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:34–46. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smeltzer M S, Gillaspy A, Pratt F L, Thames M D. Comparative evaluation of use of cna, fnbA, fnbB, and hlb for genomic fingerprinting in the epidemiological typing of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2444–2449. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2444-2449.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tambic A, Power E G M, Talsania H, Anthony R M, French G L. Analysis of an outbreak of non-phage-typeable methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by using a randomly amplified polymorphic DNA assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3092–3097. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3092-3097.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenover F C, Arbeit R, Archer G, Biddle J, Byrne S, Goering R, Hancock G, Hébert G A, Hill B, Hollis R, Jarvis W R, Kreiswirth B, Eisner W, Maslow J, McDougal L K, Michael J, Mulligan M, Pfaller M A. Comparison of traditional and molecular methods of typing isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:407–415. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.407-415.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watts J L, Washburn P J. Evaluation of the Staph-Zym system with staphylococci isolated from bovine intramammary infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:59–61. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.59-61.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witold A F, Davis W C, Hamilton M J, Park Y H, Deobald C F, Fox L, Bohach G. Activation of bovine lymphocyte subpopulations by staphylococcal enterotoxin C. Infect Immun. 1998;66:573–580. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.573-580.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]