Author contributions

Dr Guzmán‐Pérez had full access to all of the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Guzmán‐Pérez contributed to study concept and design. Puerta‐Peña, Rodríguez‐Peralto and Sanz‐Bueno contributed to acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Guzmán Pérez, Puerta‐Peña, Falkenhain‐López, Montero‐Menárguez and Gutierréz‐Collar contributed to drafting of the manuscript. Rodriguez‐Peralto and Sanz‐Bueno contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Guzmán Pérez, Puerta‐Peña, Falkenhain‐López, Montero‐Menárguez and Gutierréz‐Collar contributed to administrative, technical or material support. Rodriguez‐Peralto and Sanz‐Bueno contributed to study supervision.

Funding sources

None.

Conflict of interest

None.

Disclosure

All authors have submitted a completed ICMJE disclosure form. There are no relationships/activities/interests related to the content of the manuscript to declare.

Dear Editor,

The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused significant economic and socio‐sanitary effects on a global level. Its high transmission capacity coupled with the lack of effective treatment led to the rapid development of vaccines that, today, have been administered in a wide list of countries. As a result, new postvaccination adverse events continue to be described.

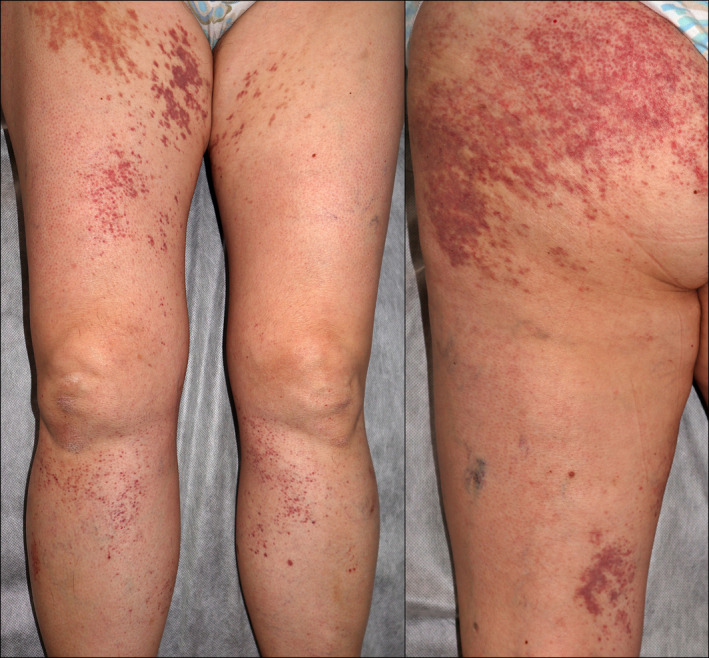

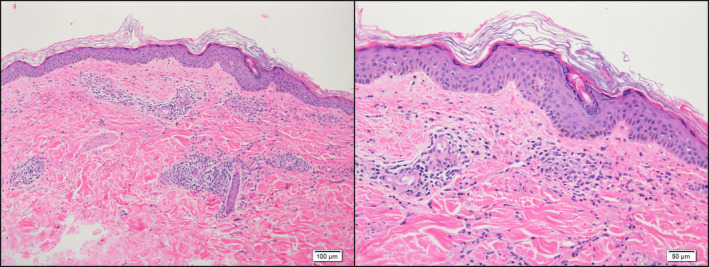

A 57‐year‐old woman with a personal history of hypertension and hypothyroidism presented to the emergency room for skin lesions of 4 days of evolution. Five days prior to the onset of symptoms, she had received the first dose of the Oxford‐AstraZeneca COVID‐19 vaccine and within the next 24 h of the administration, she presented with a fever of up to 38.5°C, generalized myalgias and general malaise with local pain at the injection site that self‐limited without treatment. She denied previous similar episodes or recent use of new drugs. She denied any associated systemic symptoms or having previously had SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. On examination, she presented confluent palpable purpura lesions in the buttocks and in a splashed way in the legs and arms, being in the latter location practically resolved (Fig. 1). Histological examination revealed an intact epidermis and, in the dermis, a neutrophil‐predominant perivascular infiltrate with leukocytoclasia and some eosinophils, features consistent with small‐vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Fig. 2). Direct inmunofluorescence was negative. Further work‐up with blood and urine tests showed a slight increase in C‐reactive protein and no other abnormalities. Complementary examinations were negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and cryoglobulins, and serology for hepatotropic viruses and HIV was negative. A rapid diagnostic test for COVID was also performed, which was negative. On follow‐up without treatment 5 days later, she presented postinflammatory pigmentation and no new lesions were seen.

Figure 1.

Physical examination showed palpable purpura lesions in the buttocks and in a splashed way in the legs.

Figure 2.

Histopathology a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate with leukocytoclasia consisting predominantly of neutrophils and some eosinophils, consistent with small‐vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis (original magnification ×10 & ×20).

Cutaneous small‐vessel vasculitis is an inflammatory process that primarily affects the dermal postcapillary venules. It is often idiopathic but may be secondary to an underlying cause such as infection or medication. 1 Although it is controversial whether vaccination can be considered a promotor of any kind of vasculitis or not, several types of vasculitis have been reported in temporal association with their administration. A systematic review revealed that influenza vaccine is the most often reported in postvaccination cases of vasculitis. 2 Postvaccination vasculitis pathogenesis remains unclear although an innate immunity‐mediated response to viral agents or vaccine excipients via molecular mimicry has been proposed. 3

Vasculitis after COVID‐19 vaccination has already been reported. A recent study that evaluated 417 cases of cutaneous reactions after mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines found a frequency of 2.9% and 0.7% of vasculitis after the first dose of Pfizer (New York, NY, USA)‐BioNTech (Mainz, Germany) (BNT162b2) and Moderna (mRNA‐1273) vaccine, respectively. 4

Moreover, cases of vasculitis secondary to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection have also been reported, 5 , 6 although there is still no solid evidence about the role of SARS‐CoV‐2 in the etiopathogenic mechanism of the skin lesions. 6

The Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID‐19 vaccine (AZD1222) is based on a chimpanzee modified adenovirus (ChAdOx1) expressing the spike protein of SARS‐CoV‐2, which allows development of a humoral and cellular immune response against the virus. 7 During the phase 2/3 clinical trial of the Oxford‐Astrazeneca vaccine, injection site pain and tenderness were the most common local adverse reactions reported, whereas fatigue, headache, feverishness and myalgia were the most common systemic adverse reactions. 8 In that study, no vasculitis was reported as an adverse reaction and we have not found published cases in the literature of vasculitis after Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID‐19 vaccination.

Given the recent commercialization of this vaccine, the report of new and potentially severe cutaneous adverse events is highly recommended to better characterize the vaccine security profile and study the potential association between vasculitis and COVID‐19 vaccines.

Acknowledgements

The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to the publication of their case details. The authors confirm that the manuscript has been submitted solely to this journal and is not submitted, in press, or published in any language elsewhere. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

References

- 1. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatología, 4th edn. Elsevier, Barcelona, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bonetto C, Trotta F, Felicetti P et al. Vasculitis as an adverse event following immunization – systematic literature review. Vaccine 2016; 34: 6641–6651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agmon‐Levin N, Paz Z, Israeli E et al. Vaccines and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2009; 5: 648–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID‐19 vaccination: a registry‐based study of 414 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 85: 46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mayor‐Ibarguren A, Feito‐Rodriguez M, Quintana‐Castedo L et al. Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis secondary to COVID‐19 infection: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e541–e542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Camprodon Gómez M, González‐Cruz C, Ferrer B et al. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis in a patient with COVID‐19 with positive SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR in skin biopsy. BMJ Case Rep 2020; 13: e238039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Billy E, Clarot F, Depagne C et al. Thrombotic events after AstraZeneca vaccine: What if it was related to dysfunctional immune response? Therapies 2021; 76: 367–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ramasamy MN, Minassian AM, Ewer KJ et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19 vaccine administered in a prime‐boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single‐blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2020; 396: 1979–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]