Abstract

Background and Aim

One of the most impacted regions by the pandemic globally, Latin America is facing socioeconomic and health‐care challenges that can potentially affect disease outcomes. Recent data suggest that inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients do not have an increased risk of the development of COVID‐19 complications. However, the impact of COVID‐19 on IBD patients living in least developed areas remains to be fully elucidated. This study aims to describe the outcomes of IBD patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 in countries from Latin America based on data from the SECURE‐IBD registry.

Methods

Patients from Latin America enrolled in the SECURE‐IBD registry were included. Descriptive analyses were used to summarize clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. The studied outcomes were (i) a composite of need for intensive care unit admission, ventilator use, and/or death (primary outcome) and (ii) a composite of any hospitalization and/or death (secondary outcome). Multivariable regression was used to identify risk factors of severe COVID‐19.

Results

During the study period, 230 cases (Crohn's disease: n = 115, ulcerative colitis: n = 114, IBD‐unclassified [IBD‐U]: n = 1) were reported to the SECURE‐IBD database from 13 different countries. Primary outcome was observed in 17 (7.4%) patients, and the case fatality rate was 1.7%. In the adjusted multivariable model, the use of systemic corticosteroids (odds ratio [OR] 10.97; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.44–34.99) was significantly associated with the primary outcome. Older age (OR 1.03; 95% CI: 1.00–1.05), systemic corticosteroids (OR 9.33; 95% CI: 3.84–22.63), and the concomitant presence of one (OR 2.14; 95% CI: 0.89–5.15) or two (OR 10.67; 95% CI: 1.74–65.72) comorbidities were associated with the outcome of hospitalization or death.

Conclusion

Inflammatory bowel disease patients with COVID‐19 in Latin America appear to have similar outcomes to the overall global data. Risk factors of severe COVID‐19 are similar to prior reports.

Keywords: COVID‐19, Crohn's disease, Latin America, Ulcerative colitis

Introduction

The COVID‐19 pandemic has emerged as the most significant global health challenge of the 21st century. As of March 13, 2021, the number of confirmed cases worldwide passed 115 million across almost 200 countries with a total death toll of more than 2 million. 1 Latin America has been one of the most affected regions with one of the highest COVID‐19 death rates in the world, as a consequence of fragile health care systems and longstanding socioeconomic inequality. 2 As of March 8, 2021, a total of 957.9 thousand people have died due to COVID‐19 in Latin America and the Caribbean. 3 In addition, many Latin American countries are having delays in their vaccination programs, likely resulting in a continued high burden of COVID‐19 in the region.

Patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are considered to be more susceptible to infections, especially when they have active disease and are on immunosuppressive therapy. 4 However, recently published data suggest that IBD patients do not have an increased risk of infection of SARS‐CoV‐2 or the development of COVID‐19 complications. 5 Nevertheless, the impact of COVID‐19 on IBD patients remains to be fully elucidated.

Despite the lack of precise data, there has been an increase in the incidence of IBD in Latin America and the Caribbean according to a recent systematic review. 6 Therefore, the prevalence of IBD in Latin America is similar to many countries in Asia and is approximating countries in Southern and Eastern Europe. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) increased significantly in patients with Crohn's disease (CD), but to a lesser extent in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) in the region.

The Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SECURE‐IBD) was developed in order to collect information from IBD patients globally with confirmed COVID‐19 infection and its clinical characteristics, outcomes, and complications. An initial analysis of 525 IBD patients from the registry showed that increasing age, comorbidities, and corticosteroids were associated with higher risk of complications of COVID‐19 and that treatment with TNFi was not associated with severe SARS‐COV‐2 infection. 5 Recently, based on data from over 1400 IBD patients, another report from the same registry described that the combination of thiopurines with TNFi and thiopurine monotherapy are associated with significantly increased risk of severe COVID‐19 as compared with TNFi monotherapy. 7 Regardless of the risk related to IBD medications, it seems clear that maintaining patients in remission with steroid‐sparing treatments may be crucial during the pandemic period.

It is likely that people living in least developed areas may face potential health‐related risks, especially in the context of a pandemic. For instance, it has been demonstrated that Black and Hispanic populations in the USA have higher coronavirus‐related infections, hospitalizations, and death rates probably as a consequence of poor living and working conditions and other factors such as insurance status. 8 , 9 It has become a great social, economic, and political challenge to face the COVID‐19 pandemic in Latin America, a region, which includes both developing and newly industrialized countries. These areas may face different socioeconomic and health‐care issues that can potentially affect disease outcomes. In this context, we aimed to describe the presentation and evolution of IBD patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 in countries from Latin America based on data from the SECURE‐IBD registry.

Methods

Data source

This study utilized data on patients from the SECURE‐IBD registry (www.covidibd.org). The SECURE‐IBD registry is an international collaborative effort that created a web‐based database of IBD patients with COVID‐19 that has been previously described. 5 Health‐care professionals voluntarily reported cases of laboratory confirmed COVID‐19 cases in IBD patients. Health‐care providers were instructed to report cases, regardless of severity, after a minimum of 7 days from symptom onset with sufficient time having passed to inform the disease course about resolution of acute illness or death. For the present analyses, we used SECURE‐IBD data collected from inception (March 13, 2020) to November 24, 2020.

Study population

Latin America consists of 20 countries and some dependent territories, including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Only patients from 13 of them were enrolled on SECURE‐IBD registry (Table S1). We included all adults and pediatric patients from Latin America that were enrolled in SECURE‐IBD registry during the study period. No exclusion criteria were considered.

Included variables

The registry records the following information: age, country of residence, state of residence (if applicable), year of COVID‐19 diagnosis, name of center/practice/physician providing care, sex, race, ethnicity, height, weight, patient's diagnosis (CD, UC, or inflammatory bowel disease‐unclassified [IBD‐U]), disease activity (as defined by physician global assessment [PGA]), medications at time of COVID‐19 diagnosis, need for hospitalization, gastrointestinal symptoms related to COVID‐19, specific COVID‐19 treatment options, and COVID‐related mortality or complications. For patients who needed hospitalization, the name of hospital, length of stay, need for ICU admission, and need for a ventilator were also documented. Our primary outcome was the occurrence of severe COVID‐19 defined as a composite of need for ICU admission, ventilator use, and/or death. The secondary outcome was a composite of any hospitalization and/or death.

Ethical considerations

In agreement with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Safe Harbor De‐Identification standards, the SECURE‐IBD survey met criteria for deidentified data and did not need IRB (institutional review board) approval.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to summarize clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages and continuous variables using means and standard deviations.

The association between sociodemographic and clinical variables with outcomes was analyzed using a multivariable logistic regression.

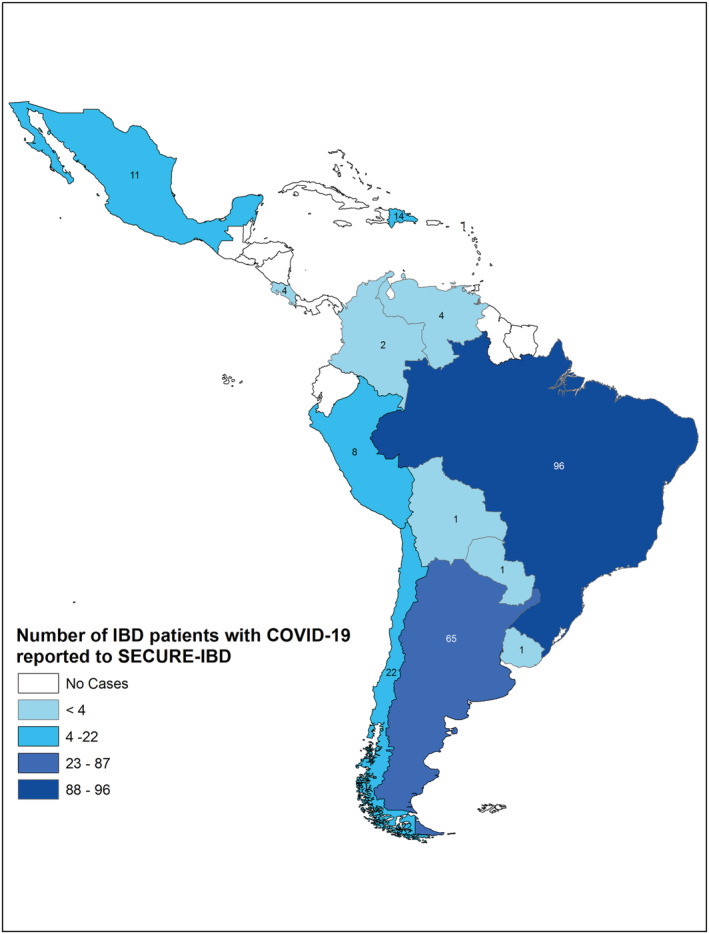

IBD cases according to Latin American countries were presented as absolute frequency distribution. We used ArcGIS 10.2 to create a choropleth map and classified the cases of IBD into four categories (<4, 4–23, 24–87, and 88–96 cases/country) based on data from 13 different countries to allow comparisons between the studies. 5

Logistic regression was used to estimate the effect of potential explanatory variables. Two models were obtained, being one crude model and one adjusted multivariate model. The crude model tested the univariate association of age, sex, diagnosis (CD vs UC/IBD‐U), IBD disease activity (remission, mild, moderate, and severe), body mass index (>30 km/m2), comorbidities (none, 1, 2, or more), healthy behavior (current smoker), and IBD medication on the pre‐established outcomes (intensive care unit [ICU], ventilator use or death and hospitalization or death). These variables were selected according to existing published data. 7 , 10 The variables that presented statistically significant association in the crude model (P < 0.05) were included in the adjusted multivariate model. All data analysis was conducted using spss version 22.0, and a level of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, a total of 230 cases were reported to the SECURE‐IBD database from 13 different countries (Fig. 1). The countries with the highest reported cases were Brazil (n = 96, 41.7%), followed by Argentina (n = 65, 28.3%) and Chile (n = 22, 9.6%) (These data are described in detail in Table S1.).

Figure 1.

Number of cases from each Latin American country from SECURE‐IBD database.

Demographic, clinical, and IBD treatment‐related characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 40.47 (±16.2) years, and there was a predominance of female individuals (59.6%). Most cases were reported in white individuals (n = 167, 72.6%). Ethnicity was reported as Hispanic/Latino in 81.3% of cases (n = 187). There was an equal distribution between patients regarding IBD diagnosis (CD: n = 115, 50%; UC: n = 114, 49.6%; IBD‐U: n = 1, 0.4%). IBD disease activity according to PGA was classified as remission in 48.3% (n = 111) of cases. The most common class of IBD treatment was aminosalicylates (n = 96, 41.7%). Frequency of use of other medications is described in Table 1. Most patients (65.7%) had no comorbidities other than IBD. Current smokers comprised seven (3%) patients.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of SECURE‐IBD cohort in Latin American patients (n = 230)

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 40.47 | 16.2 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 92 | 40.0 |

| Female | 137 | 59.6 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.4 |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 167 | 72.6 |

| Not White | 63 | 27.4 |

| Hispanic/Latino, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 187 | 81.3 |

| No | 24 | 10.4 |

| Unknown | 17 | 7.4 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.9 |

| Disease type, n (%) | ||

| CD | 115 | 50.0 |

| UC | 114 | 49.6 |

| IBD‐unspecified | 1 | 0.4 |

| IBD disease activity, n (%) | ||

| Remission | 111 | 48.3 |

| Mild | 54 | 23.5 |

| Moderate | 49 | 21.3 |

| Severe | 15 | 6.5 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.4 |

| IBD medication, n (%) | ||

| Any medication | 218 | 94.8 |

| Sulfasalazine/mesalamine | 96 | 41.7 |

| Budesonide | 5 | 2.2 |

| Oral/parenteral steroids | 32 | 13.9 |

| 6MP/azathioprine monotherapy | 30 | 13.0 |

| Methotrexate monotherapy | 3 | 1.3 |

| Anti‐TNF without 6MP/AZA/MTX | 59 | 25.7 |

| Anti‐TNF + 6MP/AZA/MTX | 33 | 14.3 |

| Anti‐integrin | 13 | 5.7 |

| IL‐12/23 inhibitor | 20 | 8.7 |

| JAK inhibitor | 1 | 0.4 |

| Other IBD medication | 2 | 0.9 |

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | ||

| Any condition | 79 | 34.3 |

| Cardiovascular disease (e.g. CAD, heart failure, and arrhythmia) | 8 | 3.5 |

| Diabetes | 8 | 3.5 |

| Lung disease (e.g. asthma and COPD) | 13 | 5.7 |

| Hypertension | 25 | 10.9 |

| Cancer | 1 | 0.4 |

| History of stroke | 2 | 0.9 |

| Chronic renal disease (e.g. CKD) | 1 | 0.4 |

| Chronic liver disease (e.g. PSC, NAFLD, and cirrhosis) | 10 | 4.3 |

| Other | 30 | 13.0 |

| Current smoker | 7 | 3.0 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms, n (%) | ||

| Any increase in baseline IBD symptoms | 156 | 68.1 |

| Abdominal pain | 27 | 11.7 |

| Diarrhea | 62 | 27.0 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 22 | 9.6 |

| Other | 4 | 1.7 |

| Medications and/or investigational therapies used in COVID‐19 treatment, n (%) | ||

| Remdesivir | 1 | 0.4 |

| Chloroquine | 3 | 1.3 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 9 | 3.9 |

| Oseltamivir | 5 | 2.2 |

| Corticosteroids | 16 | 7.0 |

| Other | 51 | 22.2 |

| No medications and/or investigational therapies were used | 140 | 60.9 |

CAD, coronary artery disease; CD, Crohn's disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NAFLD, non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Outcome data by demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 2. Overall, 15 patients were admitted in an ICU (6.5%), and seven needed a ventilator (3%). The primary outcome (ICU/ventilator/death) was observed in 17 (7.4%) patients. Of these, 5 (15.2%) occurred in patients ≥60 years of age versus 0 of 18 pediatric cases (<20 years). Only one of 18 pediatric patients (5.6%) required hospitalization; none required ICU or ventilator support. The secondary outcome (hospitalization and/or death) was observed in 47 (20.4%) patients. As described on Table S2, two patients required ICU admission, needed ventilator support, and died. Five patients were admitted to an ICU, used ventilator, and survived. Eight patients required ICU, but did not require ventilator support and survived. Two patients did not need ICU or ventilator support, but died.

Table 2.

Outcomes by demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics

| Total | Hospitalized | ICU | Ventilator | Death | ICU/ventilator/death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | % | n | % | N | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Overall | 277 | 47 | 20.4 | 15 | 6.5 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 1.7 | 17 | 7.4 |

| Age, years | |||||||||||

| 0–9 | 4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 10–19 | 14 | 1 | 7.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 20–29 | 40 | 4 | 10.0 | 2 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.5 | 3 | 7.5 |

| 30–39 | 61 | 11 | 18.0 | 2 | 3.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.3 |

| 40–49 | 49 | 9 | 18.4 | 4 | 8.2 | 3 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 8.2 |

| 50–59 | 26 | 7 | 26.9 | 3 | 11.5 | 2 | 7.7 | 1 | 3.8 | 3 | 11.5 |

| 60–69 | 23 | 11 | 47.8 | 3 | 13.0 | 1 | 4.3 | 1 | 4.3 | 3 | 13.0 |

| 70–79 | 6 | 2 | 33.3 | 1 | 16.7 | 1 | 16.7 | 1 | 16.7 | 2 | 33.3 |

| ≥80 | 4 | 1 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 92 | 20 | 21.7 | 11 | 8.0 | 5 | 3.6 | 1 | 0.7 | 11 | 8.0 |

| Female | 137 | 27 | 19.7 | 4 | 4.3 | 2 | 2.2 | 3 | 3.3 | 6 | 6.5 |

| Disease type | |||||||||||

| CD | 115 | 21 | 18.3 | 6 | 5.2 | 3 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 5.2 |

| UC/unspecified | 115 | 26 | 22.6 | 9 | 7.8 | 4 | 3.5 | 4 | 3.5 | 11 | 9.6 |

| IBD disease activity | |||||||||||

| Remission | 111 | 18 | 16.2 | 5 | 4.5 | 2 | 1.8 | 2 | 1.8 | 6 | 5.4 |

| Mild | 54 | 9 | 16.7 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.9 | 2 | 3.7 |

| Moderate/severe | 64 | 20 | 31.2 | 9 | 14.1 | 4 | 6.3 | 1 | 1.6 | 9 | 14.1 |

| Smoking | |||||||||||

| Non‐smoker | 223 | 45 | 20.2 | 14 | 6.3 | 7 | 3.1 | 4 | 1.8 | 16 | 7.2 |

| Current smoker | 7 | 2 | 28.6 | 1 | 14.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14.3 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||||

| 0 | 177 | 26 | 14.7 | 7 | 4.0 | 3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 4.0 |

| 1 | 43 | 13 | 30.2 | 4 | 9.3 | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 2.3 | 5 | 11.6 |

| 2 | 5 | 4 | 80.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 2 | 40.0 |

| 3+ | 5 | 4 | 80.0 | 3 | 60.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 3 | 60.0 |

CD, Crohn's disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ICU, intensive care unit; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Patients with more comorbidities also experienced a higher proportion of adverse outcomes. As described on Table 2, 40% (2 out of 5) and 60% (3 out of 5) of patients with at least two comorbidities and with three or more comorbidities experienced the primary outcome, respectively. While only 4% of patients (seven out of 177) with no comorbidities required ICU admission, ventilation, or died. Ten (31.3%) out of 32 patients on systemic corticosteroids needed ICU admission, ventilator or died, while 5.1% (3 out of 59) and 9.1% (3 out of 33) of patients on anti‐TNF monotherapy and combination therapy, respectively, met the primary outcome. No association was demonstrated between race (White/non‐White) and the studied outcomes (Table S3). Additional outcome data, stratified by medication use, are shown in Table S4.

The four deaths (1.7% of reported cases) occurred in patients with UC (Table 2), and all had at least one concomitant comorbidity. There were no fatalities reported in the CD population in our cohort. Additional data on deaths are shown in Table S5.

In the univariate analysis, thiopurine monotherapy was associated with the primary outcome and the use of systemic corticosteroids and presence of comorbidities demonstrated statistical significance with both primary and secondary outcomes as described on Table 3. In the adjusted multivariate model (Table 3), the use of systemic corticosteroids (odds ratio [OR] 10.97; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.44–34.99) and thiopurine monotherapy (4.538; 95% CI: 1.105–18.627) were significantly associated with the primary outcome. No significant association was observed between TNFi use and the primary outcome (OR 0.81; 95% CI: 0.29–2.26). Older age (OR 1.03; 95% CI: 1.00–1.05), systemic corticosteroids (OR 9.33; 95% CI: 3.84–22.63), and the concomitant presence of one (OR 2.14; 95% CI: 0.89–5.15) or two (OR 10.67; 95% CI: 1.74–65.72) comorbidities were associated with the outcome of hospitalization or death.

Table 3.

Multivariable regression for primary and secondary outcomes from SECURE‐IBD cohort

| ICU/vent/death | Hospitalization or death | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||

| Variable (referent group) | n (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | n (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P |

| Age | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.03 | 1.01 (0.97–1.04) | 0.80 | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 0.04 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 6 (6.5) | 1.00 | 20 (21.7) | |||||||

| Female | 11 (8.0) | 1.25 (0.47–3.51) | 0.67 | 27 (19.7) | 0.88 (0.46–1.69) | 0.71 | ||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Crohn's disease (ulcerative colitis/IBD unspecified) | 6 (5.2) | 1.00 | 21 (18.3) | |||||||

| UC/unspecified | 11 (9.6) | 1.92 (0.69–5.38) | 0.21 | 26 (22.6) | 1.31 (0.69–2.49) | 0.41 | ||||

| Disease severity | ||||||||||

| Remission | 6 (5.4) | 18 (16.2) | ||||||||

| Active disease (active/moderate/severe) | 11 (9.3) | 1.80 (0.64–5.04) | 0.26 | 29 (24.6) | 1.68 (0.87–3.22) | 0.12 | ||||

| Systemic corticosteroid | ||||||||||

| No | 7 (3.5) | 28 (14.1) | ||||||||

| Yes | 10 (31.3) | 12.40 (4.29–35.87) | <0.001 | 10.97 (3.44–34.99) | <0.001 | 19 (59.4) | 8.87 (3.94–19.96) | <0.001 | 9.33 (3.84–22.63) | <0.001 |

| TNF antagonist | ||||||||||

| No | 11 (8.0) | 30 (21.7) | ||||||||

| Yes | 6 (6.5) | 0.81 (0.29–2.26) | 0.68 | 17 (18.5) | 0.82 (0.42–1.59) | 0.55 | ||||

| Current smoker | ||||||||||

| No | 16 (7.2) | 45 (20.2) | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (14.3) | 2.16 (0.24–19.02) | 0.49 | 2 (28.6) | 1.58 (0.30–8.42) | 0.59 | ||||

| BMI>30 | ||||||||||

| No | 11 (8.5) | 40 (21.2) | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (5.0) | 0.57 (0.07–4.53) | 0.59 | 4 (20.0) | 0.93 (0.30–2.94) | 0.90 | ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||

| None | 7 (4.0) | 26 (14.7) | ||||||||

| 1 | 5 (11.6) | 3.20 (0.96–10.61) | 0.06 | 3.03 (0.83–11.10) | 0.94 | 13 (30.2) | 2.52 (1.16–5.45) | 0.02 | 2.14 (0.89–5.15) | 0.09 |

| ≥2 | 5 (50.0) | 24.29 (5.69–103.73) | <0.001 | 17.31 (2.56–116.85) | 0.003 | 8 (80.0) | 23.23 (4.67–115.57) | <0.001 | 10.70 (1.74–65.72) | 0.01 |

| 5‐ASA/sulfasalazine | ||||||||||

| No | 6 (9.7) | 16 (25.8) | ||||||||

| Yes | 11 (6.5) | 0.65 (0.23–1.85) | 0.42 | 31 (18.5) | 0.65 (0.32–1.30) | 0.22 | ||||

| 6MP/azathioprine monotherapy | ||||||||||

| No | 12 (6.0) | 41 (20.5) | ||||||||

| Yes | 5 (16.7) | 3.13 (1.02–9.64) | 0.05 | 4.54 (1.11–18.63) | 0.04 | 6 (20.0) | 0.97 (0.37–2.54) | 0.95 | ||

5‐ASA, 5 aminosalicylate acid drugs; 6MP, mercaptopurine; BMI, body mass index; CD, Crohn's disease; CI, confidence interval; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ICU, intensive care unit; UC, ulcerative colitis; Vent, ventilator.

Discussion

We report the characteristics and outcomes of IBD patients with COVID‐19 in Latin America using data derived from the SECURE‐IBD registry. So far, no large international reports detailing the outcomes of Latin American IBD patients who develop COVID‐19 have been described. Based on results from 230 patients with IBD from 13 countries, we observed an overall case fatality rate of 1.7%, with 7.4% of reported cases experiencing a composite outcome of ICU admission, need for ventilator support, and/or death. As compared with the latest updated data from the entire registry, the outcomes appear to be similar to those reported in IBD patients across the world (www.covidibd.org, as of January 30, 2021). Risk factors for worse COVID‐19 outcomes were older age, number of comorbidities, and use of systemic corticosteroids. The use of specific IBD medications was not associated with more severe COVID‐19 in our study.

In this study, we observed 4 deaths, which occurred in ulcerative colitis male patients, three of whom were older than 50 years. Due to the small number of events, it was not possible to identify possible associations for this particular outcome. However, it is important to highlight that all deaths occurred in patients with at least one comorbidity, and three of these patients were taking corticosteroids. In a recent systematic review and meta‐analysis by Aziz et al., comprising five studies, which incorporated outcomes of 151 IBD patients developing COVID‐19, the rates of hospitalization and ICU admission were 40.3% (95% CI, 24.6%–56.1%; I 2 = 68.9%) and 8.6% (95% CI, 0.2%–17.0%; I 2 = 72.6%), respectively, and the mortality rate was 6.3% (95% CI, 2.5%–10.1%; I 2 = 0%). 10 The higher rate of worse outcomes in this analysis needs to be interpreted with caution due to the low number of included cases. In our cohort, the fatality rate (1.7%) is largely consistent with previously reported data from the overall SECURE‐IBD database (3.4%) 7 and for the general population (2.1%), 1 providing reassurance that COVID‐19 course in IBD patients in Latin America appears to be comparable with the general population.

An association between the use of TNFi at COVID‐19 diagnosis and adverse outcomes was not observed in this Latin American subgroup of patients, which is in line with other similar smaller cohorts, which may be due to being underpowered. 11 , 12 However, previous larger studies demonstrated that exposure to thiopurines may increase the risk for viral infections. 13 , 14 Accordingly, our study showed that thiopurine monotherapy was significantly associated with a higher risk of severe COVID‐19. This is in line with previous data from the SECURE‐IBD database, which demonstrated that combination therapy with TNFi and thiopurines and monotherapy with thiopurines were associated with an increased risk of severe COVID‐19. This seems to be largely driven by the influence of thiopurines given that monotherapy with TNFi was not an independent risk factor for higher COVID‐related morbidity. 7 In addition, it has been speculated that treatment with TNFi might even protect against severe disease by attenuating viral induced “cytokine release storm” reported in COVID‐19. 15

Biologic penetration in therapeutic algorithms in Latin America is variable. A previous systematic review demonstrated that the use of biologics in CD varied from 1.51% in Mexico up to 46.9% in Colombia (most studies have demonstrated 20–40% of CD patients are on TNFi). 16 Use of TNFi in UC is even lower, reaching a maximum of 16.2% in Mexico. Despite the general concept that there is lower frequency of use of biologics in Latin America as compared with North America and Europe, we believe that this probably did not impact the results of our study. Overall use of biologics in the international cohort of SECURE‐IBD was 63.4%, a comparable number with the 54.4% of the current Latin American cohort here described. This similar percentage of patients on biological therapy may be reflected by the fact that local physicians who included data in the SECURE‐IBD registry are probably working in referral centers and follow specific IBD guidelines. This may also partially account for the relatively low mortality rate from our cohort. These data may be driven by patients from more developed regions in each country, from private health‐care systems, and may not reflect the reality from public health‐care systems over the continent. Reinforcing this hypothesis, a recent retrospective analysis of data from a large, nationwide surveillance database including data from over 250 000 COVID‐related hospitalizations in Brazil showed that COVID‐19 in‐hospital mortality was higher than the reported in European cohorts (38%), even among young patients, and it was associated with underlying regional differences in the supply of hospital and ICU beds and worsened by existing regional disparities within the health system. 17

Increasing age and the presence of comorbidities have consistently been described as risk factors for COVID‐19 complications. 18 , 19 In our cohort, older age, the use of corticosteroid, and comorbidities were associated with worse outcomes of COVID‐19. Additionally, the rate of corticosteroid use in our cohort was nearly twice as frequent (13.9%) as previously reported in the entire SECURE‐IBD database (7%). 5 This finding could reflect local practice patterns and raises awareness for the urgent need to maintaining patients in remission with steroid‐sparing treatments during the pandemic period.

Our study is associated to some limitations and potential biases, which may impact interpretation of data. The number of cases reported to the SECURE‐IBD registry from Latin America is relatively small in comparison with the expected number of COVID‐19 cases in IBD patients, which may represent a reporting bias. In addition, the small sample size and event rates hinder the conduction of multivariable modeling, and data must be interpreted with caution. Moreover, we worked with a convenience sample, and the study was not specifically powered to detect the influence of specific characteristics in pre‐defined outcomes. Despite these limitations, the strengths of this study include the robust, worldwide collaboration that allowed the inclusion of a representative sample of IBD patients from Latin America. Moreover, the validity of the data is reinforced by the physician‐reported nature of this database. Additionally, our findings were consistent with previous analyses from the entire SECURE‐IBD database. This is, to date, the largest and most complete analysis of COVID‐19 outcomes in IBD patients from Latin America.

Even though the data presented here could be influenced by reporting bias, this analysis of Latin American patients from the SECURE‐IBD registry demonstrated similar findings than the overall global data. IBD patients with COVID‐19 in Latin America did not appear to have significantly worse outcomes. The risk factors of poor outcomes with COVID‐19 are similar to prior reports.

Supporting information

Table S1. Countries/territories of origin of included patients.

Table S2. Primary outcome.

Table S3. Association between race and the study outcomes.

Table S4. IBD medications. ICU: intensive care unit.

Table S5. Deaths of COVID‐19 or other complications caused by or contributed to COVID‐19.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all health‐care providers worldwide who have reported cases to the SECURE‐IBD database, the organizations who supported or promoted the SECURE‐IBD registry, and the SECURE‐IBD team. (Reporter names available at www.covidibd.org/reporter‐acknowledgment/).

Queiroz, N. S. F. , Martins, C. A. , Quaresma, A. B. , Hino, A. A. F. , Steinwurz, F. , Ungaro, R. C. , and Kotze, P. G. (2021) COVID‐19 outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in Latin America: Results from SECURE‐IBD registry. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 36: 3033–3040. 10.1111/jgh.15588.

Declaration of conflict of interest N. S. F. Q. has served as a speaker and advisory board member of Janssen, Takeda, and AbbVie. A. A. F. H. and C. A. M. have no conflict of interest. A. B. Q. has received fees for serving as a speaker for AbbVie and Janssen. He also does clinical research for Roche. P. G. K. is a speaker and consultant for AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda. He also does clinical research for Lilly, Takeda, and Pfizer. R. C. U. has served as an advisory board member or consultant for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda; research support from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer. F. S. is a speaker, consultant, and researcher for AbbVie, Novartis, Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer, Sandoz, Takeda, and UCB.

Funding none for this specific study. There is a general funding for the creation and maintenance of the SECURE‐IBD database: the Helmsley Charitable Trust (2003‐04445), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR002489), a T32DK007634 (EJB), and a K23KD111995‐01A1 (RCU). Additional funding provided by Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, AbbVie, Lilly, Genentech, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, and Arenapharm.

References

- 1. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web‐based dashboard to track COVID‐19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020. May; 20: 533–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lancet T. COVID‐19 in Latin America: a humanitarian crisis. Lancet 2020. Nov; 396: 1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Statista . Number of deaths due to the novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) in Latin America and the Caribbean as of August 20, 2020, by country. [Internet]. 2020;16:1–2. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1103965/latin‐america‐caribbean‐coronavirus‐deaths/ [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C et al. Second European evidence‐based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brenner EJ, Ungaro RC, Gearry RB et al. Corticosteroids, but not TNF antagonists, are associated with adverse COVID‐19 outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: results from an international registry. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 481–419. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kotze PG, Underwood FE, Damião AOMC et al. Progression of inflammatory bowel diseases throughout Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019; 18: 1–9. 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ungaro RC, Brenner EJ, Gearry RB et al. Effect of IBD medications on COVID‐19 outcomes: results from an international registry. Gut 2020, 70: 725–732. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ogedegbe G, Ravenell J, Adhikari S et al. Assessment of racial/ethnic disparities in hospitalization and mortality in patients with COVID‐19 in New York city. JAMA Netw. Open 2020. Dec; 3: e2026881–e2026881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Podewils LJ, Burket TL, Mettenbrink C et al. Disproportionate incidence of COVID‐19 infection, hospitalizations, and deaths among persons identifying as Hispanic or Latino—Denver, Colorado, March–October 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2020. Dec; 69: 1812–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aziz M, Fatima R, Haghbin H, Lee‐Smith W, Nawras A. The incidence and outcomes of COVID‐19 in IBD patients: a rapid review and meta‐analysis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020. Sep; 26: e132–e133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bezzio C, Saibeni S, Variola A et al. Outcomes of COVID‐19 in 79 patients with IBD in Italy: an IG‐IBD study. Gut 2020. Jul; 69: 1213–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodríguez‐Lago I, de la Piscina PR, Elorza A, Merino O, de Zárate JO, Cabriada JL. Characteristics and prognosis of patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic in the Basque Country (Spain). Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 781–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kirchgesner J, Lemaitre M, Carrat F, Zureik M, Carbonnel F, Dray‐Spira R. Risk of serious and opportunistic infections associated with treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2018; 155: 337–346 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wisniewski A, Kirchgesner J, Seksik P et al. Increased incidence of systemic serious viral infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease associates with active disease and use of thiopurines. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019; 69: 1812–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feldmann M, Maini RN, Woody JN et al. Trials of anti‐tumour necrosis factor therapy for COVID‐19 are urgently needed. Lancet 2020; 395: 1407–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quaresma AB, Coy CSR, Damião AOMC, Kaplan G, Kotze PG. Biological therapy penetration for inflammatory bowel disease in Latin America: current status and future challenges. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2019; 56: 318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ranzani OT, Bastos LSL, Gelli JGM et al. Characterisation of the first 250,000 hospital admissions for COVID‐19 in Brazil: a retrospective analysis of nationwide data. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021; 9: 407–418. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30560-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020; 382: 1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mao R, Liang J, Shen J et al. Implications of COVID‐19 for patients with pre‐existing digestive diseases. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020; 5: 425–427. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30076-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Countries/territories of origin of included patients.

Table S2. Primary outcome.

Table S3. Association between race and the study outcomes.

Table S4. IBD medications. ICU: intensive care unit.

Table S5. Deaths of COVID‐19 or other complications caused by or contributed to COVID‐19.