Abstract

Background and Aim

Patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) develop a profound cytokine‐mediated pro‐inflammatory response. This study reports outcomes in 10 patients with COVID‐19 supported on veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV‐ECMO) who were selected for the emergency use of a hemoadsorption column integrated in the ECMO circuit.

Materials and Methods

Pre and posttreatment, clinical data, and inflammatory markers were assessed to determine the safety and feasibility of using this system and to evaluate the clinical effect.

Results

During hemoadsorption, median levels of interleukin (IL)−2R, IL‐6, and IL‐10 decreased by 54%, 86%, and 64%, respectively. Reductions in other markers were observed for lactate dehydrogenase (−49%), ferritin (−46%), d‐dimer (−7%), C‐reactive protein (−55%), procalcitonin (−76%), and lactate (−44%). Vasoactive‐inotrope scores decreased significantly over the treatment interval (−80%). The median hospital length of stay was 53 days (36–85) and at 90‐days post cannulation, survival was 90% which was similar to a group of patients without the use of hemoadsorption.

Conclusions

Addition of hemoadsorption to VV‐ECMO in patients with severe COVID‐19 is feasible and reduces measured cytokine levels. However, in this small series, the precise impact on the overall clinical course and survival benefit still remains unknown.

Keywords: cardiovascular pathology, cardiovascular research, perfusion

Abbreviations

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BMI

body mass index

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FiO2

fraction of inspired oxygen

- HIT

heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia

- IL

interleukin

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- PaO2

partial pressure of oxygen

- PCO2

partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- P/F ratio

partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio

- VV‐ECMO

veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) often develop a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) that may result in hemodynamic instability and multisystem organ failure. 1 Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines are reported in the peripheral blood and lung tissue of critically ill patients with COVID‐19, which correlate with disease severity and mortality. 2 Mechanical ventilation is required in approximately 20% of patients admitted with COVID‐19 for progressive hypoxic or hypercarbic respiratory failure and is associated with a mortality rate of 24%–74%. 3 , 4 Veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV‐ECMO) has been employed in select patients with COVID‐19 failing mechanical ventilation. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Once supported on ECMO, there are limited effective therapeutic options targeting the dysregulated immune response in patients with severe COVID‐19. 9 We previously reported excellent survival with this modality in a subset of patients who required VV‐ECMO at our institution. 5

Experience from prior hyperinflammatory syndromes suggests that reducing levels of circulating cytokines and pro‐inflammatory mediators may help attenuate an excessive immune response, limiting further tissue injury and leading to clinical recovery. 10 , 11 Three types of blood purification modalities are available, including filtration, dialysis, and adsorption. International registries have been created to evaluate the feasibility and safety of hemoadsorption devices for patients with COVID‐19, including the oXiris membrane (Baxter), the Spectra Optia Apheresis System (Terumo BCT Inc.), and CytoSorb™ (CytoSorbents, Inc.). 12

CytoSorb is an extracorporeal polystyrene‐based hemoadsorption device designed to filter blood inflammatory mediators based on molecular size and concentration, including cytokines, chemokines, and bacterial exotoxins. 9 In early 2020, it received a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) emergency use authorization for integration into bypass, ECMO, or dialysis circuits in patients with COVID‐19. Some clinical benefits, including clearance of lactate, reduced vasopressor requirement, and improved survival, have been reported in case series for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and in patients with uncontrolled septic shock. 13 , 14 , 15 In patients with SIRS following prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass and in patients undergoing surgery for infective endocarditis, the use of hemoadsorption is associated with hemodynamic stabilization and reversal of organ dysfunction. 16 , 17 In addition, this device has been shown to be compatible with ECMO without an increase in adverse events. 18 , 19

The therapeutic consequence of active reduction of inflammatory cytokines and mediators in patients with severe COVID‐19 is unknown. During the COVID‐19 pandemic, we obtained emergency use authorization for CytoSorb in patients with severe COVID‐19 and respiratory failure requiring VV‐ECMO. This study reports inflammatory and clinical outcomes in patients with severe COVID‐19 treated at our institution. The primary aim was to assess the safety and feasibility of hemoadsorption in this population. Secondarily, we assessed the anti‐inflammatory efficacy of adsorption by comparison of pre and posttreatment levels of cytokines, inflammatory markers, and clinical parameters.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A single‐institution retrospective analysis was conducted of patients with severe COVID‐19 and respiratory failure placed on VV‐ECMO, with the addition of hemoadsorption at New York University Langone Health from March 10, 2020 to June 30, 2020. Cytosorb adsorption is not currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. In the midst of the COVID‐19 pandemic, however, we obtained emergency use authorization for select patients. The primary objective of this study was to determine the safety and feasibility of hemoadsorption therapy based on clinical outcomes, including adverse events and survival. Secondarily, pre and posttreatment levels of select cytokines, biochemical data, and inflammatory markers were assessed to determine treatment effect. All data were collected in a prospective database and demographic, clinical, and outcomes data were collected retrospectively from the electronic medical record. Follow‐up was performed until hospital discharge, or 90 days post cannulation, whichever occurred first. Study design, emergency use authorization, and data management were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at New York University Langone Health (IRB #S20‐01189). Additionally, IRB approval was granted for informed consent to be obtained from family members and/or health care decision‐makers on the patient's behalf given the severity of illness and need for sedation.

2.1. Patient selection and management

The diagnosis of COVID‐19 was established by nasal pharyngeal swab for reverse‐transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay. Patients were evaluated, cannulated for VV‐ECMO, and managed by a multidisciplinary team of cardiothoracic surgeons and critical care physicians. 5 Entry and inclusion criteria were based on the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (Pao 2)‐to‐fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio 2) ratio (P/F ratio), arterial blood gas, ventilator settings, and patient functional status, comorbidities, and hemodynamic status. ECMO support was only offered to patients with a P/F ratio of less than 150 mmHg or a pH of less than 7.25 with a partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (Paco 2) exceeding 60 mm Hg. 5 A lung‐protective ventilation strategy was employed with titration of ECMO circuit flow, which was maintained above 3 L/min to limit oxygenator thrombosis. Oxygenator FiO2 was maintained at 1.0 for the entirety of support. The sweep gas flow rate was adjusted to achieve a goal partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) less than 45 mm Hg. Anticoagulation using intravenous heparin infusion was used to achieve a partial thromboplastin time goal of 50–70 and/or anti‐Xa level more than 0.15 units/ml based on prior experience. 11 , 12 , 20 Vasopressors were used as needed to maintain a mean arterial pressure goal of 60 mm Hg.

The ECMO multidisciplinary team also evaluated patients for hemoadsorption. Hemoadsorption was added to the circuit in selected patients based on severity of illness—those who had progressive clinical decline while supported on VV‐ECMO—including assessment of the P/F ratio, arterial blood gas values, ventilator, and ECMO settings, and hemodynamic status, particularly if those requiring high dose vasopressors. Patients with thrombocytopenia less than 20,000/µl or with a history of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) were excluded per established contraindications to use. There were no other absolute exclusion criteria.

2.2. Hemoadsorbption

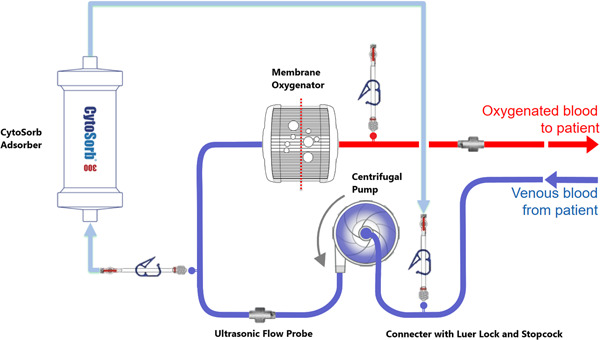

In select patients on VV‐ECMO, a hemoadsorption column (300 ml device) was installed in parallel with the ECMO circuit in a pre‐hemofilter position (Figure 1). Filtered blood returned to the venous line before the centrifugal pump. An additional ultrasonic flow probe was placed to calculate flow through the cartridge. All device integrations and exchanges required a brief suspension of ECMO. Treatment was planned for a 72‐h duration with device exchange every 12 h for the first 24 h, then 24 h thereafter, or as needed in the event of cartridge thrombosis.

Figure 1.

Diagram of CytoSorb Incorporation into the VV‐ECMO Circuit. Illustration elements used with permission from CytoSorbents. VV‐ECMO, veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses for categorical variables are reported in Tables 1 and 3 as frequency and percentage. Continuous variables are reported as means and standard deviations or errors for normally distributed variables and as either means and range or medians and interquartile ranges for non‐normally distributed variables. Single one‐way analysis of variance test was performed for inflammatory and cytokine markers for data compiled per group time points of (−1 day before treatment), during the course (24, 48, and 72 h), and post (2–3 days after removal) to assess changes in overall profile. Inflammatory, metabolic, and clinical data reported in Table 3 evaluated differences in the mean changes per patient as defined as each corresponding patient's change in status over time as: %Change = (Posttreatment – Pretreatment)/(Pretreatment), with negative values indicating a decrease. A p value less than .05 was predetermined to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with R software, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and SPSS.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with COVID‐19 on VV‐ ECMO with or without CytoSorb

| Variable | VV‐ECMO + CytoSorb, N = 10 |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 45 (37–51) |

| Sex, No (%) | |

| Male | 9 (90%) |

| Female | 1 (10%) |

| Race, No (%) | |

| Latino/Hispanic | 5 (50%) |

| White/Caucasian | 4 (40%) |

| Asian/Asian American | 1 (10%) |

| Black/African American | 0 (0%) |

| Other/not‐specified | 0 (0%) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 33 (30–37) |

| Smoking history, No (%) | |

| Never smoker | 7 (70%) |

| Current smoker | 0 (0%) |

| Former smoker | 1 (10%) |

| Not assessed/unknown | 2 (20%) |

| Comorbid conditions, No (%) | |

| None | 2 (20%) |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 8 (80%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 (30%) |

| Hypertension | 2 (20%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (10%) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 1 (10%) |

| Immunocompromised | 0 (0%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 0 (0%) |

| Heart failure | 0 (0%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 (0%) |

| Chronic liver disease | 0 (0%) |

| Rheumatologic or autoimmune disease | 0 (0%) |

| Interventions before ECMO | |

| Prone positioning | 7 (70%) |

| Neuromuscular blockade | 6 (60%) |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | 4 (40%) |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy | 1 (10%) |

| At time of VV‐ECMO cannulation, median (IQR) | |

| Arterial blood gas | |

| pH | 7.24 (7.07–7.41) |

| PO2 | 67 (62–70) |

| PCO2 | 63 (41–86) |

| PaO2/FiO2 (P:F ratio) | 85 (65–106) |

| Mechanical ventilation settings | |

| Plateau pressure, cm H2O | 31 (25.5–34) |

| Peak inspiratory pressure, cm H2O | 32 (30–36) |

| FiO2, % | 100 (75–100) |

| Positive end‐expiratory pressure | 13 (12–14.5) |

| Vasopressor requirement | 7/10 (70%) |

| Vasopressor inotrope score | 4.79 (−4.4 to 14) |

| Hospital days before mechanical ventilation, median (IQR) | 2.5 (0–11) |

| Hospital days with mechanical ventilation before VV‐ECMO cannulation, median (IQR) | 1.5 (0.75–2.5) |

| Hospital days before VV‐ECMO cannulation, median (IQR) | 4.5 (1.8–11.5) |

| Days on VV‐ECMO before CytoSorb, median (IQR) | 1 (0–3) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; VV‐ECMO, veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 2.

Adverse events during CytoSorb treatment period

| Patient | Change out #1 12 h | Change out #2 12 h | Change out #3 24 h | Change out #4 24 h | Adverse event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No events | ||||

| 2 | No events | ||||

| 3 | No events | ||||

| 4 | No events | ||||

| 5 | No events | ||||

| 6 | D/C | Filtered sedatives; treatment discontinued after 18 h | |||

| 7 | No events | ||||

| 8 | No events | ||||

| 9 | No events | ||||

| 10 | HIT | D/C | Progressive thrombocytopenia, HIT positive; treatment discontinued after 60 h | ||

Abbreviations: C, cartridge exchange; D/C, discontinued; HIT, heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia.

3. RESULTS

From March 10, 2020 to June 30, 2020, 10 patients with respiratory failure from severe COVID‐19 underwent VV‐ECMO cannulation with the addition of hemoadsportion. Median age was 45 (IQR 37–51), predominantly male (90%), with a median body mass index (BMI) of 33 kg/m2 (IQR 30–37) and the majority had no diagnosed prior medical history besides obesity. At the time of VV‐ECMO cannulation, patients selected for hemoadsorption had a median pH of 7.24 (IQR 7.07–7.41), (PCO2) of 63 (IQR 41–86), and a P:F ratio of 85. Before cannulation, seven patients (70%) required vasopressor and/or inotropic hemodynamic support with a median vasoactive inotrope score was 4.79. Patients selected for hemoadsorption were hospitalized for a median of 4.5 days (IQR 1.8–11.5) before ECMO and were supported on EMCO a median of 1 day (IQR 0–3) before the initiation of treatment. Baseline demographic information and clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1.

3.1. Hemoadsorption

Of the 10 patients selected for hemoadsorption, eight patients completed a full 72‐h treatment duration, and there were no complications or adverse events in eight patients (Table 2). One patient was removed from treatment after 24 h due to an inability to maintain adequate paralysis and sedation, which subsequently improved with cessation of hemoadsorption. Another patient developed HIT and the device was removed after 60 h of treatment. There was no evidence of progressive end‐organ injury attributed to therapy with reductions in median levels of pre and posthemoadsorption in creatinine (−7%) and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase levels (−10%/−40%).

Table 3.

Inflammatory, metabolic, and clinical data after 72‐h CytoSorb treatment, or parallel interval on ECMO alone

| Variable | VV‐ECMO + CytoSorb, n = 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | % change* | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L, median (IQR) | 856 (718–1115) | 425 (370–644) | −49 (−61 to −31) |

| Ferritin, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 2647 (1306–2815) | 1004 (576–2031) | −46 (−62 to −41) |

| d‐Dimer, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 5517 (2619–9363) | 4188 (2911–8810) | −7 (−22 to 0) |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 117 (31–263) | 64 (7.8–105) | −55 (−75 to −47) |

| Procalcintonin, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 1.2 (0.21–3.8) | 0.19 (0.08–15) | −76 (−100 to −51) |

| Lactate, mmol/L, median (IQR) | 1.60 (1.32–2.55) | 1.35 (1.08–1.53) | −44 (−63 to −9.4) |

| IL‐2R, pg/ml, median (IQR) | 2143 (1147–15201) | 1279 (1097–2293) | −54 (−100 to −4.3) |

| IL‐6, pg/ml, median (IQR) | 22 (9–618) | 11 (7–146) | −86 (−100 to −31) |

| IL‐10, pg/ml, median (IQR) | 18 (9.5–73) | 5 (5–83) | −64 (−100 to −27) |

| Hemotocrit, %, median (IQR) | 33 (30–36) | 30 (27–32) | −9 (−14 to 8.3) |

| Absolute lymphocyte count, 1000/µl, median (IQR) | 5 (1.5–5) | 6 (4–11) | +140 (0 to 280) |

| Platelet count, 1000/µl, median (IQR) | 215 (138–262) | 94 (35–138) | −60 (−76 to −25) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L, median (IQR) | 39 (26–66) | 28 (21–79) | −10 (−43 to −2.6) |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L, median (IQR) | 41 (25–72) | 23 (20–56) | −40 (−42 to −10) |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 1.1 (0.8–2.3) | 1.4 (0.6–1.8) | −7 (−21 to 13) |

| pH, median (IQR) | 7.38 (7.28–7.42 | 7.42 (7.37–7.44) | 1 (0.3 to 1) |

| PCO2, mm Hg, median (IQR) | 42 (41–51) | 43 (41–44) | −1 (−13 to 10) |

| FiO2, %, median (IQR) | 40 (40–40) | 40 (40–45) | 0 (0 to 12.5) |

| PaO2/FiO2 (P:F ratio), median (IQR) | 185 (152–225) | 185 (170–260) | −9 (−34 to 6) |

| Vasopressin inotropic score, median (IQR) | 4.52 (0–12.25) | 1 (0–2.68) | −80 (−91 to −36) |

Abbreviations: FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; IL, interleukin; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide.

Grouped %change reported as per individual patient as (72 h – Pre)/Pre, mean of change p < .05.

3.2. Cytokines, inflammatory, and biochemical data

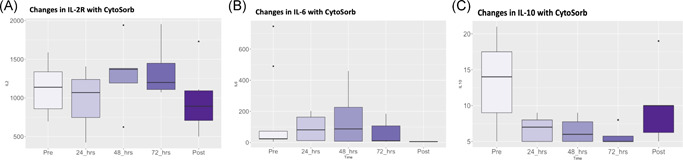

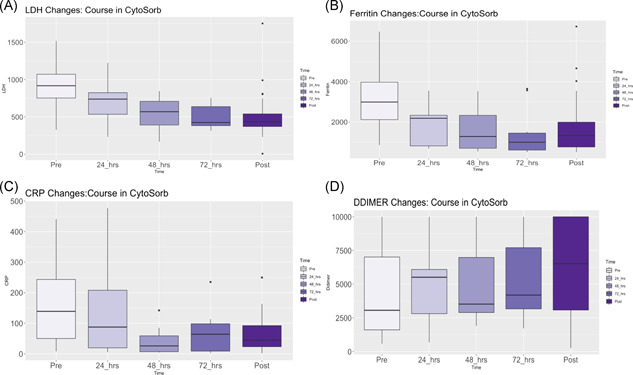

After the planned 72‐h treatment course, patients who underwent hemoadsorption, had a median decrease in levels of interleukin (IL) 2 Receptor (IL‐2R), IL‐6, and IL‐10 by 54%, 86%, and 64%, respectively (Figure 2). Reductions in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (−49%), ferritin (−46%), d‐dimer (−7%), C‐reactive protein (−55%), procalcitonin (−76%), and lactate (−44%) were also observed (Figure 3). All pre and posttreatment cytokine, inflammatory, and biochemical data are reported in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Changes in cytokine levels during Cytosorb hemoadsorption on VV‐EMCO, (A) IL‐2R, (B) IL‐6, (C) IL‐10. IL, interleukin; VV‐ECMO, veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Figure 3.

Changes in inflammatory makers during Cytosorb Hemoadsorption on VV‐ECMO, (A) lactate dehydrogenase, (B) ferritin, (C) C‐reactive protein, (D) d‐dimer. VV‐ECMO, veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

3.3. Clinical outcomes

Overall survival of patients who underwent hemoadsorption on VV‐ECMO was 90% (9/10 patients) (Table 4) with a median length of stay of 47 days (IQR 34–88) and a median of 22 days (IQR 13–64) on VV‐ECMO. Lung recovery, defined as the interval between intubation until the patient was on room air for 24 h, was achieved in median 34 days (IQR 26–51) in patients who underwent hemoadsorption. A single patient who underwent CytoSorb remained admitted at 90‐days post ECMO cannulation with ongoing respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Although this is not a comparative study, for context, 90‐day survival was also 90% in patients on VV‐ECMO who did not undergo hemoadsorption therapy.

Table 4.

Clinical outcomes and survival

| Variable | VV‐ECMO + CytoSorb, N = 10 |

|---|---|

| Intubation to room air for 24‐h, days, median (IQR) | 34 (26–51) |

| VV‐ECMO, days, median (IQR) | 22 (13–64) |

| Total hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 47 (34–88) |

| Survival | 9 (90%) |

| Discharged | 8 (80%) |

| Hospitalized at 90 days | 1 (10%) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; VV‐ECMO, veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

4. DISCUSSION

In a single‐institution study of patients with severe COVID‐19 and respiratory failure placed on VV‐ECMO, 10 patients were selected for the addition of hemoadsorption to the circuit. Our data support the feasibility of this treatment for patients with COVID‐19 on VV‐ECMO with limited adverse events. During the treatment interval, patients had reductions in circulating cytokines and reductions in clinically relevant inflammatory markers. Equally, patients rapidly cleared their vasopressor requirement. Given the limited sample size and heterogeneous clinical course of these complex patients with severe COVID‐19, the overall clinical contribution of hemoadsorption towards pulmonary recovery and overall survival, remains unknown despite the favorable trends observed in reduction of inflammatory profile.

There were limited adverse events associated with integration of the column and eight patients (80%) completed a full 72‐h treatment duration (Table 2). In the setting of full heparin anticoagulation in all patients, thrombocytopenia was observed in the majority of patients (60%). This reduction, however, did not result in bleeding events. Previous series of critically ill patients undergoing hemoadsorption have reported modest reductions in platelet count, which were typically mild (<10%) and self‐limiting. 21 In our series, one patient developed HIT and was removed from treatment after 60 h. It was unclear, however, whether the device was the precipitating factor for HIT. In our previously published series, 4/17 patients (24%) with severe COVID‐19 on VV‐ECMO without hemoadsorption, tested positive for HIT by platelet factor 4 antibody assay, two of which were confirmed positive by serotonin release assay. Given these findings, nonetheless, close monitoring for thrombocytopenia and HIT during hemoadsorption is warranted. Additionally, in three patients, the device required unplanned exchange for cartridge thrombosis, all of which were of low clinical impact.

Three patients required increased dosing of sedatives and neuromuscular blockade agents, including one patient who was removed from treatment after 24 h due to an inability to maintain adequate paralysis and sedation. A number of in‐vitro and in‐vivo studies have shown reduced or eliminated levels of analgesics, sedatives, and antibiotics during hemoadsorption. 22 Given the multifaceted pharmacologic regimens of patients with severe COVID‐19, it is critical to consistently asses the patient's physical exam and monitor drug levels to assure adequate therapeutic delivery during hemoadsorption.

Elevated levels of cytokines and inflammatory mediators in patients with COVID‐19 correlate with disease severity, supporting the notion of an uncontrolled cytokine storm. 2 Patients receiving hemoadsorption had significant decreases in pro‐inflammatory (IL‐2R by 54%; and IL‐6 by 86%) and anti‐inflammatory (IL‐10 by 64%) cytokines. International registry data have shown similar significant reductions of IL‐6 with hemoadsorption in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients. 23 Equally, patients treated with hemoadsorption had reductions in LDH (−49%), ferritin (−46%), d‐dimer (−7%), C‐reactive protein (−55%), procalcitonin (−76%), and lactate (−44%).

The clinical consequence of the clearance of inflammatory mediators remains unanswered; the number of patients in this series is small and the study is underpowered to detect subtle differences. Given that the use of hemoadsorption was through an emergency use authorization in the context of an evolving pandemic, we were not able to perform a comparative trial of patients on ECMO with and without hemoadsorption. There were, however, some notable clinical outcomes observed. Of the seven patients requiring vasopressor and/or inotropic support pre‐CytoSorb, only two required hemodynamic support afterinitiation of hemoadsorption and these levels were significantly reduced. The pre and posttreatment median vasopressin inotropic scores decreased by 80% during the 3‐day treatment interval. In patients who underwent VV‐ECMO with CytosSorb, median hospital length of stay was 53 days (36–85) and survival was 90% with eight patients discharged and one patient hospitalized at 90‐days post ECMO cannulation. This patient was discharged to an acute rehabilitation facility after a 160 day length of stay and discharged home after 33 days of rehabilitation.

The survival rate in this series is substantially higher than other institutional reports of patients on VV‐ECMO for COVID‐19, with survival to discharge rates between 56.8% and 62%. 7 , 8 In this small study, the causal contribution of hemoadsorption towards respiratory recovery and survival is unproven. Furthermore, in the patients on hemoadsorption, the column was removed after 72 h of usage. It is unclear if longer duration of support would have contributed to clinical recovery. This study is further limited by its retrospective, single‐center design with limited sample size, and is therefore underpowered for definitive lung recovery or survival analysis. Patients were selected for the addition of hemoadsorption in a nonrandom fashion based on severity of illness. There was an inherent selection bias, therefore, for patients with more severe disease, given the lack of clear inclusion or exclusion criteria. Given the limited therapeutic options available for severely ill patients supported on VV‐ECMO, however, we instituted the compassionate use of hemoadsorptionvia emergency use authorization. Furthermore, the results are confounded by the multitude of additional treatments and interventions that were used to treat these complex patients with COVID‐19. Ultimately, randomized trials with defined treatment algorithms will be required to establish definable clinical benefits of hemoadsorption in patients with severe COVID‐19.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Use of hemoadsorption with VV‐ECMO in patients with severe COVID‐19 respiratory failure is feasible with limited adverse events. Hemoadsorption was associated with thrombocytopenia and filtration of certain medications including sedatives and neuromuscular blockade agents, which warrants close clinically monitoring. In this pilot study, patients on hemoadsorption had greater reductions in clinically relevant inflammatory markers, lactate, and reduction in vasopressor requirements. Positive contribution to clinical course and survival remains unclear Additional research is necessary to define the role of hemoadsorption in patients with severe COVID‐19.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Dr. Geraci, Dr. Smith, Dr. Chen, Dr. Chang, Dr. Fargnoli, Dr. Carillo, and Dr. Alimi have no disclosures. Dr. Kon discloses a financial relationship with Medtronic, Inc. and Breethe, Inc.; Dr. Moazami with Medtronic, Inc.; Dr. Pass obtained a grant from NYU Langone Health for COVID‐related research; and Dr. Galloway with Edward Lifesciences and Medtronic, Inc.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Travis C. Geraci: Data analysis/interpretation, drafting article, critical revision of article, data collection, and statistics. Zachary N. Kon: Concept/design, data analysis/interpretation, and critical revision of article. Nader Moazami: Drafting article, concept/design, data analysis/interpretation, and critical revision of article. Stephanie H. Chang: Concept/design and data collection. Julius Carillo: Concept/design, data collection. Stacey Chen, MD: Concept/design, data collection, statistics. Anthony Fargnoli: Concept/design, data collection, and statistics. Marjan Alimi: Concept/design, data collection, and statistics. Harvey Pass: Concept/design, data collection, and statistics. Aubrey Galloway: Concept/design, data analysis/interpretation, and critical revision of article. Deane E. Smith: Concept/design, data analysis/interpretation, and critical revision of article.

Geraci TC, Kon ZN, Moazami N, et al. Hemoadsorption for management of patients on veno‐venous ECMO support for severe COVID‐19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Card Surg. 2021;36:4256‐4264. 10.1111/jocs.15785

REFERENCES

- 1. Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the 'Cytokine Storm' in COVID‐19. J Infect. 2020;80(6):607‐613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052‐2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID‐19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763‐1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kon ZN, Smith DE, Chang SH, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in severe COVID‐19. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;111(2):537‐543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mustafa AK, Alexander PJ, Joshi DJ, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for patients with COVID‐19 in severe respiratory failure. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(10):990‐992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, et al. Extracorporeal life support organization. extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID‐19: an international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1071‐1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shih E, DiMaio JM, Squiers JJ, et al. Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for patients with refractory coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): multicenter experience of referral hospitals in a large health care system [published online ahead of print December 1, 2020]. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soy M, Keser G, Atagündüz P, Tabak F, Atagündüz I, Kayhan S. Cytokine storm in COVID‐19: pathogenesis and overview of anti‐inflammatory agents used in treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(7):2085‐2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Napp LC, Ziegeler S, Kindgen‐Milles D. Rationale of hemoadsorption during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Blood Purif. 2019;48(3):203‐214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lother A, Benk C, Staudacher DL, et al. Cytokine adsorption in critically ill patients requiring ECMO support. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swol J, Lorusso R. Additive treatment considerations in COVID‐19: the clinician's perspective on extracorporeal adjunctive purification techniques. Artif Organs. 2020;44(9):918‐925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mitzner SR, Gloger M, Henschel J, Koball S. Improvement of hemodynamic and inflammatory parameters by combined hemoadsorption and hemodiafiltration in septic shock: a case report. Blood Purif. 2013;35(4):314‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Akil A, Ziegeler S, Reichelt J, et al. Combined use of CytoSorb and ECMO in patients with severe pneumogenic sepsis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;69:246‐251. 10.1055/s-0040-1708479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kogelmann K, Jarczak D, Scheller M, Drüner M. Hemoadsorption by CytoSorb in septic patients: a case series. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Träger K, Fritzler D, Fischer G, et al. Treatment of post‐cardiopulmonary bypass SIRS by hemoadsorption: a case series. Int J Artif Organs. 2016;39(3):141‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Träger K, Skrabal C, Fischer G, et al. Hemoadsorption treatment of patients with acute infective endocarditis during surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: a case series. Int J Artif Organs. 2017;40(5):240‐249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kogelmann K, Scheller M, Drüner M, Jarczak D. Use of hemoadsorption in sepsis‐associated ECMO‐dependent severe ARDS: A case series. J Intensive Care Soc. 2020;21(2):183‐190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bonavia A, Groff A, Karamchandani K, Singbartl K. Clinical utility of extracorporeal cytokine hemoadsorption therapy: a literature review. Blood Purif. 2018;46(4):337‐349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. CytoSorb , Manufacture Guideline, CytoSorb 300 mL Device: Approved by FDA for Emergency Treatment of COVID‐19. https://cytosorb-therapy.com/en-us/

- 21. Ankawi G, Xie Y, Yang B, Xie Y, Xie P, Ronco C. What have we learned about the use of Cytosorb adsorption columns? Blood Purif. 2019;48(3):196‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zoller M, Döbbeler G, Maier B, Vogeser M, Frey L, Zander J. Can cytokine adsorber treatment affect antibiotic concentrations? A case report. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(7):2169‐2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Friesecke S, Träger K, Schittek GA, et al. International registry on the use of the CytoSorb adsorber in ICU patients: study protocol and preliminary results. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2019;114(8):699‐707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]