Abstract

Objectives

In the current study, we aimed to explore the experiences and attitudes among healthcare professionals as they transitioned from their familiar disciplines to respiratory medicine, intensive care or other departments during the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Background

In preparation for the increasing number of patients suspected of having or who would be severely ill from COVID‐19, a major reconstruction of the Danish Healthcare System was initiated. The capacity of the healthcare system to respond to the unprecedented situation was dependent on healthcare professionals’ willingness and ability to engage in these new circumstances. For some, this may have resulted in uncertainty, anxiety and fear.

Design

The study was a descriptive study using semi‐structured focus group interviews.

Healthcare professionals (n = 62) from seven departments were included, and 11 focus group interviews were conducted. The focus group interviews took place during June 2020. Analyses was conducted using thematic analysis. The current study was reported using the consolidated criteria for reporting Qualitative research (COREQ).

Results

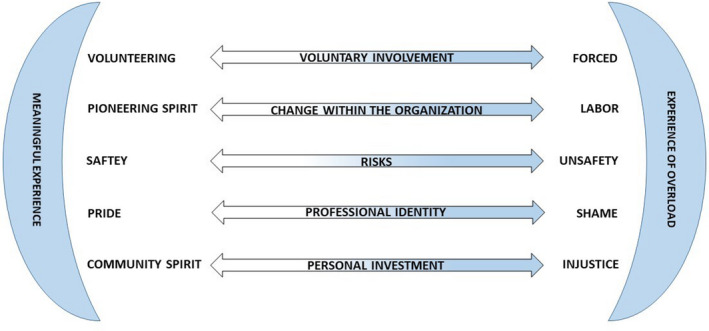

Healthcare professionals experiences was described by five themes: 1) Voluntary involvement, 2) Changes within the organisation, 3) Risks, 4) Professional identity and 5) Personal investment. Common to all five themes was the feeling of being on a pendulum from a meaningful experience to an experience of mental overload, when situations and decisions no longer seemed to be worthwhile.

Conclusions

Healthcare professionals experienced a pendulum between a meaningful experience and one of mental overload during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The swinging was conditioned by the prevailing context and was unavoidable.

Relevance to clinical practice. To balance the continuous pendulum swing, leaders must consider involvement, and to be supportive and appreciative in their leader style. This is consistent with a person‐centred leadership that facilitates a well‐adjusted work‐life balance and may help prevent mental overload developing into burnout.

Keywords: burnout, experience, Focus group, healthcare workers, work satisfaction

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community.

During a pandemic, healthcare professionals experience being on a pendulum between a meaningful experience and one of mental overload.

Person‐centred leadership seems to facilitate a balanced work‐life experience during pandemics.

Involvement of healthcare professionals in workplace decisions may prevent an experience of work overload.

A meaningful work‐life balance enhances patient safety during pandemics.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) first appeared in Wuhan, Hubei Province in China in December 2019. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the spread of COVID‐19 as a pandemic on 11 March 2020. In Europe, the first registered case was reported in France on 24 January 2020 (Situation update worldwide, as of 10 April 2020, 2020), and the first large outbreak was experienced in Italy (Perico et al., 2020). The very short time from the first outbreak in Wuhan until we became aware of the impact in Europe left us with too little time to prepare sufficiently. This caused a great strain on healthcare professions. This paper reports lessons learned from healthcare professionals’ (HP) experiences and attitudes as they transitioned from their familiar disciplines to working on the COVID‐19 frontline.

2. BACKGROUND

In Denmark, the initial stage of handling the COVID‐19 pandemic started on 12 March 2020, when the Danish Health Authority increased the number of hospitals and departments that could treat COVID‐19 patients. Thus, a major reconstruction of the Danish Healthcare System was initiated, in preparation for the increasing number of patients suspected of having or who would be severely ill from COVID‐19. The capacity of the healthcare system to respond to the unprecedented situation was dependent on HPs’ willingness and ability to engage in these new circumstances. For some HPs, facing situations without knowing what might happen and with no previous experience to draw upon, resulted in uncertainty, anxiety and fear (Nyashanu et al., 2020).

With the surge in total diagnosed cases and deaths across the world, studies began to document how the COVID‐19 pandemic affected healthcare workers’ mental health and well‐being (Nyashanu et al., 2020; Shaukat et al., 2020; Walton et al., 2020). In Denmark, a prompt lock‐down covering the whole country was initiated. Schools and universities changed to interactive teaching, people were encouraged to work from home and social activities was limited with a ban on gatherings. In addition, all hospital planned surgery and outpatient clinics were cancelled. Partly due to these essential restrictions, we prevented a spread of the COVID‐19 and the capacity of the healthcare system to cope with the pandemic was not threatened, as it was in other European countries. Nevertheless, Danish HPs were encouraged to volunteer to care for COVID‐19 patients.

In the current study, we aimed to explore the experiences and attitudes among HPs as they transitioned from their familiar disciplines to respiratory medicine, intensive care or other departments during the COVID‐19 pandemic. This is interesting, because, at time of writing, we are now facing the second wave of the pandemic, and knowledge from the first wave should be collected and taken into account in future pandemic management.

3. METHOD

The study was a qualitative descriptive study using semi‐structured focus group interviews. The qualitative research method is able to explore the complexity of human behaviour and may generate a deeper understanding of this. We chose focus group interviews as this method creates a dynamic discussion that allows group participants to easily share their opinion, whether they are agreeing or disagreeing (Halkier, 2016). We included HPs from seven departments, and conducted 11 focus group interviews with, in total, 62 participants. The purpose was to collect attitudes and exchange of experiences from different health disciplines. The focus group interviews took place during June 2020. The number of focus group participants varied between two and eight, and groups were composed of either inter‐disciplinary or mono‐disciplinary professionals. The focus group interview method was chosen because it allows for group interaction that can accentuate members’ similarities and differences, thereby providing rich information about the range of perspectives and experiences (van Eyk & Baum, 2003). Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) was used to optimise the reporting quality of the current study. The COREQ checklist is presented in Table S1.

3.1. Setting

The setting was a university hospital in Denmark that has 24 departments and 738 beds. Participants were recruited from the following departments: Surgery; Otorhinolaryngology and Maxillofacial Surgery; Haematology; Oncology and Palliative Care; Anaesthesiology; Neurology and Plastic‐ and Breast surgery.

3.2. Participants

Participants were health professionals (registered nurses, physicians, certified nursing assistants, medical secretaries, physiotherapists and psychologists) from seven departments involved in healthcare at the hospital during the COVID‐19 crisis. This created a dynamic and interactive relationship in the groups (Halkier, 2016), Table 1. The specific departments assessed which and how many focus groups could be established, based on how many health professionals were involved in the COVID‐19 preparations. The exclusion criteria were students, those employed less than three months prior to the focus group interviews, and managers. Invitations to participate were communicated by work emails to health professionals at the seven departments involved.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics, n = 62

| Years | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 41 (9) | |

| Employment in clinical practice (Range) | 0 – 39 | |

| Employment in current position (Range) | 0 – 21 | |

| Female | Male | |

| Sex, Female/Male (n) | 56 | 6 |

| Profession | Number | |

| Nurse (n) | 44 | |

| Physician (n) | 6 | |

| Certified Nursing Assistant (n) | 4 | |

| Medical secretary (n) | 5 | |

| Physiotherapist (n) | 2 | |

| Psychologist (n) | 1 | |

| Yes | No | |

| Clinical role prior to COVID‐19 (n) | 52 | 10 |

| Departmental or sectional transition due to COVID‐19 a (n) | 47 | 15 |

| Standby as COVID‐19 staff (n) | 42 | 20 |

| Participated in organised evaluation of COVID‐19 in own department (n) | 0 | 62 |

During the COVID‐19 preparation, participants served at one of the units caring for patients suffering from COVID‐19

3.3. Data collection

3.3.1. Focus group interviews

The group interviews took place at the hospital and was conducted by the authors (researchers). All researchers were nurse specialists or research leaders, they were female and had a PhD degree or were PhD students. Each department was responsible for arranging interviews in their own department. Two researchers conducted each focus group interview. The interviewer was a researcher not familiar with the informants while the second researcher served as an observer and was familiar with the informants. A semi‐structured interview guide was developed by the research group, inspired by a person‐centred approach, which mirrored the hospital's nursing theoretical framework (McCormack et al., 2017). The themes in the interview guide were as follows: participants’ experiences of skills training in relation to COVID‐19, interdisciplinary teamwork in new settings, new tasks linked to the COVID‐19 situation, caring for and treating COVID‐19 patients, management in relation to transition, and new insights. Each interview lasted 45 to 60 minutes. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were not returned to participants for verification (Table 1).

3.4. Analyses

Analyses were conducted using thematic analysis (TA), as recommended by Braun and Clarke (Braun & Clarke, 2006). TA is an accessible and theoretically flexible method of qualitative analysis that gives the researcher a method to systematically identify and organise data, in a way that provides insight into themes across the data set. Furthermore, TA is an inductive approach to data coding; the analysis is driven by the data and conducted bottom‐up. The analysis consists of a six‐phase approach, which, according to Braun and Clarke, should not be viewed as a linear model, where one cannot proceed to the next phase without completing the prior phase; rather, the analysis is a recursive process (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

The use of TA meant that the analysis focused on the explicit experiences and attitudes of the participants, so that the themes were revealed directly from the data. Thus, there was a constant search for and identification of common threads that extended across the entire set of interviews. In practice, data were read and initial ideas were noted. The material was then coded line‐by‐line across the data from the focus group interviews and codes emerged. Data were organised based on content, and faithfulness with the original interviews was maintained. The codes were then collated into potential themes. Extraction of the potential themes was led by the first author.

During a seminar, the potential themes were critically reviewed and examined by all the authors, to generate clear definitions for each main theme. During the seminar, discussions were held to ensure that the content of the main themes supported the initial ideas that had been discussed between the researchers. Inspired by the main themes that had emerged, a model representing the connectedness between themes was created, Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Healthcare professionals experienced a pendulum between a meaningful experience and one of mental overload during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The swinging was conditioned by the prevailing context and was unavoidable

3.5. Ethics

Permission to conduct the study was received from the hospital management. The Danish Data Protection Agency and the National Committee on Health Research Ethics approved the study. Written informed consent was also obtained from each participant. Participation in the focus group interviews were voluntary and participants’ confidentiality was assured by emphasising participants’ duty of confidentiality. We were aware that the participants may have had highly emotive experiences during the pandemic. Thus, time was scheduled after the interview to follow‐up on those in needed of this facilitated by the interviewer and observer, who were both experienced in this.

4. RESULTS

The analysis resulted in the following five themes: 1) Voluntary involvement, 2) Changes within the organisation, 3) Risks, 4) Professional identity and 5) Personal investment. Common to all five themes was the feeling of being on a pendulum from a meaningful experience to an experience of mental overload, when situations and decisions no longer seemed to be worthwhile. Figure 1 shows the width of the five themes.

4.1. Voluntary involvement

All healthcare HPs expressed a willingness to contribute, because the healthcare system faced an acute pandemic. However, in practice, transition from familiar disciplines to respiratory medicine, intensive care or other medical specialities only partly familiar to participants, was described on a continuum between voluntary involvement and feeling compelled to contribute, as expressed by one nurse: ‘I wanted to help. I felt like making an effort because of the way things were in our society. It made sense helping during the first 14 days, after this is was forced on us’. Volunteering was based on, for example ‘the spirit of Florence Nightingale’, facing challenging professional tasks or simply helping the management team. Meeting professional and personal challenges was described as leading to feelings of success and solidarity and, as described by one participant, it strengthened one's professional identity: ‘We can do much more than we think we can,and we certainly want to – to a certain point’. In relation to participating in the daily COVID‐19 routines, one nurse expressed: ‘I volunteered and now I can hardly get my arms down [I am thrilled with what we achieved],but I still feel high because the work is very life‐affirming’.

Reluctance towards volunteering was based on personal or professional reasons, for example one's own or a relative's chronic disease, risk of virus transmission to family, and lack of confidence in one's competencies. Feeling compelled by leaders and colleagues to accept transition led to frustration, insecurity and being out of one's comfort zone. One participant described that it resulted in a stress reaction that lasted for weeks.

Over the course of time, the initial voluntary involvement transformed into feeling compelled to contribute. Some volunteers described having worn themselves out, and expected others to take their turn. One nurse expressed: ‘I was rather frustrated … I thought, if I volunteered then I had done my part, but it did not turn out that way’.

4.2. Changes within the organisation

Among the participants, there was an agreement that the organisation on the wards was crucial to the overall experience. Ward management and planning that was based on the options available at that time, and continuously revised and adjusted in accordance with the changing requirements and expectations of all the HPs on the ward, and was experienced by the participants as positive, accommodating and involving. Furthermore, a sense of pioneer spirit arose, which encouraged a sense of influence. As expressed by a certified nursing assistant: ‘Well,of course,if it's something I am capable of,then I am pleased to participate…’. On the other hand, if the organisation was based on a culture in which some HPs had more influence than others, the participants were left with an experience of being seen as solely a labour force, fulfilling important functions, but did not have influence. This feeling could be reinforced, if the ward manager was not available when the transferred staff needed help or support. Furthermore, when the transferred staff had little or no say in when their shifts would be planned, it could be extremely difficult to plan their family life already under pressure. One nurse described how a consequence of lack of influence might lead to a sense of powerlessness and lack of motivation: ‘You could sense we were guests in the department.That is,we had to conform,and if we came up with good ideas – the answer was “we have never done it like that before.” This I think was very difficult to work with’.

4.3. Risks

This theme involved the risk of being unsafe while working with COVID‐19 patients, both for patients and HPs. Patient safety was linked to providing qualified care and treatment. The participants described how meaningful learning, and especially individually tailored ‘skills learning’, helped to strengthen and provide patient safety; as one nurse said: ‘I think we have had really good teaching. And had some good conversations about it and tried all sorts of scenario training’. However, for the instructors, providing continuous and repeated teaching resulted in the experience of burnout. One nurse referred to a conversation with one of the teachers: ‘She said to me: “I will soon not be able to do it anymore, there is training all the time” – she was completely burned out’.

One risk experienced by HPs was being able to take care of oneself using protective equipment and by gaining skills in relation to working with COVID‐19 patients. Some perceived the risk to be non‐existent, as one nurse said: ‘Of all the shifts I have had on the Covid section, I have never at any time felt that I was at high risk of being infected. It was the 8 hours a day where I was in the greatest safety zone’. Others found working with patients during COVID‐19 to entail a risk. This became explicit when one's own safety was challenged by ever‐changing guidelines, and there was too little space to maintain the guidelines and restrictions under which the rest of society lived. As stated by one nurse: ‘I had such close contact with all the staff;back then you had to have 2 metres distance, but it was impossible even to keep 1 metre distance in between us’.

4.4. Professional identity

Having to deal with sudden organisational changes in a new clinical setting meant that the participants’ professional identities were shaped in new ways. They explained how, from one day to the next, they went from being experts in a specific field to being novices in another. Being challenged to act and think in new ways, as well as master new skills or polish rusty ones, led to uncertainties, and made the participants reconsider the core elements of their profession. One nurse illustrated how the act of smiling suddenly became a conscious and difficult task:

I wish I could have shown my facial expression with a mask and a visor on. You might be able to smile with your eyes, but there is also a lot that is related to your mouth and body.

Some experienced great professional pride in contributing to the clinical work during COVID‐19. However, there were participants who experienced embarrassment and shame, as they did not succeed in solving professional tasks in a way in which they themselves were satisfied. Several also expressed that they were faced with ethical dilemmas, which made a strong impression on them. One doctor expressed:

You have to decide for yourself, in the individual situation. I have been asked to send relatives home despite thinking that people who are really sick or dying should see loved ones for support. It has caused disagreements among our staff. I think, by doing this, we deprive people of some human rights without thinking about what it means to them.

4.5. Personal investment

Participants described that it was exhausting to adjust to the new COVID‐19 organisation, with the new work features and new professional identity. They saw it as a continuous process that required a high degree of personal investment, including both energy and motivation. To some, it was difficult to find the requirements of the situation. This included the workplace requirement to participate in the COVID‐19 preparations, and at the same time a request from the home front to maintain their safety. To continue contributing at the workplace, an essential factor was a high degree of HPs overall community spirit, which was based on the idea that we may must all contribute in a national serious crises, as expressed by one nurse:

I had never been engaged in it before, but I wanted to offer my help at the Covid department … therefore I worked weekend shifts there and ended up working ten weekends in a row. I know it sounds crazy, but I had lots of holiday left, it was possible to work dayshifts and I got it the way I wanted … I was sort of a volunteer.

If the personal investment no longer resulted in a feeling of community spirit or no longer was meaningful, an experience of injustice or even burnout could arise. Two nurses expressed it like this:

We (health professionals) may seem very mentally strong, but I got up one morning and then tears just ran down my cheeks. … my body just said no, or my mind … my unconsciousness – the unconsciousness said no …, I left for work and thought: ‘well, it will probably work out’ … But it did not. I think it was very scary, and I simply thought, I will end up getting stressed, I was very emotionally affected and even talking about it today makes me feel emotional.

Several participants knew of colleagues for whom the feeling of injustice resulted in them quitting their jobs, which was described as both brave and necessary, but also sad and annoying. One nurse experienced a colleague reflecting it like this: ‘No matter what I said, I was just an unimportant rag, meaning they did not listen to me, I felt like there was nothing individual or personal at all’. (Figure 1).

5. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences and attitudes among HPs as they transitioned from known disciplines to respiratory medicine, intensive care or other departments during the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic. One main finding identified the experience of a pendulum between a meaningful experience and mental overload. Similar conflicting experiences are described in the SCARF model, which includes five domains: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness and Fairness (Rock, 2008). A feeling of ‘approach and avoid’ is a natural physiological response to interconnectedness and rapid changes. The model is based on social neuroscience that explores the biological foundations of the way humans relate to each other and to themselves. The significance of the ‘approach‐avoid’ response highlights the dramatic effect the change between the responses may have on perception and problem solving, and the implications of this on decision making, stress management, collaboration and motivation. Experiencing an approach response is synonymous with the feeling of engagement and thus being willing to do difficult things, to take risks, to think deeply about issues and develop new solutions. An avoid response inhibits one from preserving the more subtle signals required for solving non‐linear problems. The tendency is to generalise more, which increases the likelihood of accidental connections. In neuropsychology, the effect of the approach‐avoid response is explained by the physiological processes in our brain. The approach response is closely linked to positive emotions and increased dopamine levels, which are important for interest and learning. On the contrary, during the avoid response there is a strong negative correlation between the amount of threat activation, and the resources available for the prefrontal cortex. This results in less oxygen and glucose available for the brain functions involved in working memory, which impacts linear, conscious processing, and the risk of mistakes increases (Rock, 2008). The SCARF model can be used to illustrate, from a neuro‐scientific perspective, how the interpersonal experiences related to workplace transitions could activate HPs’ approach‐avoid response and thereby their ability to problem solve. Therefore, the model may support our findings where health professionals swing between a meaningful experience and an experience of overload.

Many of the HPs experienced an overload in connection to their transition to other departments during the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Our findings show that the experience of overload during the pandemic may have personal consequences, such as the sense of powerlessness, lack of motivation and an experience of exhaustion. This may result in burnout, which is a more serious condition—associated with feelings of hopelessness and inability to perform job duties effectively (Professional Quality of Life, 2020). There is, thus, a clear need for immediate action to safeguard the welfare of HPs working on the frontline (Moazzami et al., 2020). To do this, it seems important to maintain the experience of work as meaningful to avoid stress and burnout, see Figure 1.

Meaningful experiences may not always be pleasant or positive; they can include experiences that involve stress or challenge (Baumeister et al., 2013). This supports our findings in relation to HPs’ wish to contribute during the first phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Meaningful work may best be achieved by engaging in activities that draw upon one's unique talents and values (Restauri et al., 2019). According to Restauri et al., (2019) value‐aligned work protects one from experiencing burnout, which is why clarification of our values is important. This is the first step in a person‐centred approach. As shown in our study and supported by the SCARF model, in situations where the avoid response cannot be avoided and thus the risk of burnout and stress, it seems essential to be aware of balancing the avoid‐approach response through relevant involvement of the HP (Restauri et al., 2019). This is because involvement gives the individual an opportunity to adapt to new situations without being overwhelmed by a feeling of powerlessness (Rock, 2008), or a feeling of being left alone without a relation to others, who experience similar situations.

Our results showed that some participants were left with an experience of being seen as solely a labour force who were to fulfil important functions, and who did not have influence. To some, this feeling was reinforced, if the ward manager was not available and thus not able to create meaningful relationships. In a person‐centred approach to relational connectedness, contextualisation is a key issue, which, from a managerial perspective, seems necessary to focus on, to support inclusion—for example feeling welcome, connected and part of a greater whole (Eide & Cardiff, 2017). Contextualisation refers to the recognition of how a person's current being is influenced by the many contexts they inhabit as well as their past, present and future. This approach may explain why participants in our study were able to manage the radical workplace change in the short term, but felt overwhelmed when the changes no longer matched their family life (ibid). The key issue highlights the need for a holistic approach to leadership, especially in crises such as the current COVID‐19 pandemic. One important point, however, is that the leader should also be aware of not only the relational connectedness but also the contextual influence during a societal crisis, which places huge demands on the ability to make quick, safe and professionally sound decisions and the effective use of resources (Rosser et al., 2020). This duality places great demands on leaders, who must be able to handle the difficult and sometimes vulnerable leadership dance between strengthening the empowerment of the individual and utilising all available resources in the most effective way (Eide & Cardiff, 2017).

6. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The strength of this study is the variety of the data collected across different interdisciplinary professionals and departments. Malterud (2011) highlights the importance of variation within participants in qualitative research, to investigate in‐depth perspectives related to the research question (Malterud, 2011). Another strength is that, based on our rich and large number of data, we were able to develop a model that illuminates the significant clinical views during a pandemic, which future health management can encounter when mobilising preparations in health organisations.

Our study had some methodological challenges regarding using focus group interviews as a method. We chose to perform focus group interviews because they encouraged health professionals to reflect on COVID‐19 and share experiences that enriched and complemented each other. Our data material consisted of both small and large focus groups. In the small group, an everyday form of communication, knowledge and attitudes emerged. This was a strength as, it is a way of collecting data that cannot be assessed by, for example individual interviews (Halkier, 2016; Kitzinger, 1995). In the larger groups, the strength was the group discussion among several interdisciplinary perspectives, which allowed clinical differences within the health organisation as a whole to be discussed. However, the larger groups may have limited the individual participants’ opportunities to share insights, while a substantial interaction between participants is crucial in groups with few participants (Malterud, 2011; Morgan, 1997).

To elucidate the experiences of the health professionals during COVID‐19 and to elicit nuanced, in‐depth perspectives of working on the frontline, individual interviews would have strengthened our findings. Additionally, the combination of focus group interviews and individual interviews could have provided more in‐depth narratives and thereby provided more exhaustive material (Polit & Beck, 2010).

7. CONCLUSIONS

Overall, our study showed one characteristic that emerged across several themes, that is HPs experienced a pendulum between a meaningful experience and one of mental overload during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The swinging was conditioned by the prevailing context and was unavoidable. Furthermore, it was identified that health professionals’ experience of overload may cause insufficient brain functions involved in memory. To balance the continuous pendulum swing, the discussion indicated that leaders must consider involvement, and to be supportive and appreciative in their leader style. This is consistent with a person‐centred leadership that facilitates a good balanced work‐life balance and may help prevent mental overload developing into burnout.

8. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

The knowledge gained from our study shows the importance of visible and involving leadership during pandemic crises to support HPs to balance the avoid‐approach response, as seen in the SCARF model. There are already some methods to support HPs in maintaining a meaningful work‐life balance during pandemic crises—some of which were developed to facilitate self‐evaluation after stressful situations (Albott et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020). From an organisational perspective, the individual perspective must be supplemented by contextual perspectives, including considering that a pandemic is a ‘must solve situation’. This may cause a dilemma between the individual HPs’ interests and the society's acute demand for labour during the pandemic. When considering patient safety it is, however, essential to recognise that person‐centred leadership focusing on relational involvement may prevent the avoid response and thus the insufficient brain functions involved in memory, which may cause fatal errors. We may in the future develop appreciative leader strategies involving person‐centred values.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

All authors meet the criteria for authorship and all those entitled to authorship are listed as authors Approval of the final article, conceptualisation, data collection, formal analysis, and manuscript draft preparation: All authors; manuscript reviewing and editing: ER.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Rosted E, Thomsen TG, Krogsgaard M, et al. On the frontline treating COVID‐19: A pendulum experience—from meaningful to overwhelming—for Danish healthcare professionals. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30:3448–3455. 10.1111/jocn.15821

Funding information

The study did not receive any funding

REFERENCES

- Albott, C. S. , Wozniak, J. R. , McGlinch, B. P. , Wall, M. H. , Gold, B. S. , & Vinogradov, S. (2020). Battle buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R. F. , Vohs, K. D. , Aaker, J. L. , & Garbinsky, E. N. (2013). Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(6), 505–516. 10.1080/17439760.2013.830764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake, H. , Bermingham, F. , Johnson, G. , & Tabner, A. (2020). Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID‐19 on healthcare workers: A digital learning package. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 2997. 10.3390/ijerph17092997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eide, T. , & Cardiff, S. (2017). Leadership Research: A Person‐Centred Agenda. I Person‐Centred Healthcare Research, pp. 95–116, Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Halkier, B. (2016). Focus groups [Fokusgrupper]. (3ed, Bd. 2016). Samfundsslitteratur. Frederiksberg. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. BMJ, 311(7000), 299–302. 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. (2011). Qualitative methods in medical research: an introduction [Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning: En innføring]. (3ed., Bd 2011). Universitetsforlaget. Oslo. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, B. , van Dulmen, S. , Eide, H. , Skovdahl, K. , & Eide, T. (2017). Person‐Centred Healthcare Research. Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Moazzami, B. , Razavi‐Khorasani, N. , Dooghaie Moghadam, A. , Farokhi, E. , & Rezaei, N. (2020). COVID‐19 and telemedicine: Immediate action required for maintaining healthcare providers well‐being. Journal of Clinical Virology, 126, 104345. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (2nd ed., Bd. 1997). : Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Nyashanu, M. , Pfende, F. , & Ekpenyong, M. S. (2020). Triggers of mental health problems among frontline healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic in private care homes and domiciliary care agencies: Lived experiences of care workers in the Midlands region, UK. Health & Social Care in the Community, 10.1111/hsc.13204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perico, L. , Tomasoni, S. , Peracchi, T. , Perna, A. , Pezzotta, A. , Remuzzi, G. , & Benigni, A. (2020). COVID‐19 and lombardy: TESTing the impact of the first wave of the pandemic. EBioMedicine, 61, 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. , & Beck, C. (2010). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice. (7th ed., Bd. 2010). : Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Professional Quality of Life (2020). Professional Quality of Life: Elements, Theory, and Measurement. Professional Quality of Life Measure. https://www.proqol.org/Home_Page.php

- Restauri, N. , Nyberg, E. , & Clark, T. (2019). Cultivating Meaningful Work in Healthcare: A Paradigm and Practice‐ ClinicalKey. https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/playContent/1-s2.0-S0363018818303050?returnurl=https:%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0363018818303050%3Fshowall%3Dtrue&referrer= [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock, D. (2008). SCARF: a brain‐based model for collaborating with and influencing others. www.Neuroleadership.org, 1, 1–9.

- Rosser, E. , Westcott, L. , Ali, P. A. , Bosanquet, J. , Castro‐Sanchez, E. , Dewing, J. , McCormack, B. , Merrell, J. , & Witham, G. (2020). The need for visible nursing leadership during COVID‐19. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 52(5), 459–461. 10.1111/jnu.12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat, N. , Ali, D. M. , & Razzak, J. (2020). Physical and mental health impacts of COVID‐19 on healthcare workers: A scoping review. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), 40. 10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Situation update worldwide, as of 10 April 2020 . (2020). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical‐distribution‐2019‐ncov‐cases

- Walton, M. , Murray, E. , & Christian, M. D. (2020). Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care, 9(3), 241–247, 10.1177/2048872620922795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eyk, H. , & Baum, F. (2003). Evaluating health system change—Using focus groups and a developing discussion paper to compile the “voices from the field”. Qualitative Health Research, 13(2), 281–286. 10.1177/1049732302239605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material