Abstract

Aim

To describe the experiences of frontline nurses who are working in critical care areas during the COVID‐19 pandemic with a focus on trauma and the use of substances as a coping mechanism.

Design

A qualitative study based on content analysis.

Methods

Data were collected from mid‐June 2020 to early September 2020 via an online survey. Nurses were recruited through the research webpage of the American Association of Critical Care Nurses as well as an alumni list from a large, public Midwest university. Responses to two open‐ended items were analysed: (1) personal or professional trauma the nurse had experienced; and (2) substance or alcohol use, or other mental health issues the nurse had experienced or witnessed in other nurses.

Results

For the item related to psychological trauma five themes were identified from 70 nurses’ comments: (1) Psychological distress in multiple forms; (2) Tsunami of death; (3) Torn between two masters; (4) Betrayal; and (5) Resiliency/posttraumatic growth through self and others. Sixty‐five nurses responded to the second item related to substance use and other mental health issues. Data supported three themes: (1) Mental health crisis NOW!!: ‘more stressed than ever and stretched thinner than ever’; (2) Nurses are turning to a variety of substances to cope; and (3) Weakened supports for coping and increased maladaptive coping due to ongoing pandemic.

Conclusions

This study brings novel findings to understand the experiences of nurses who care for patients with COVID‐19, including trauma experienced during disasters, the use of substances to cope and the weakening of existing support systems. Findings also reveal nurses in crisis who are in need of mental health services.

Impact

Support for nurses’ well‐being and mental health should include current and ongoing services offered by the organization and include screening for substance use issues.

Keywords: content analysis, COVID‐19, mental health, nursing, psychological trauma

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic is a global phenomenon, and researchers of the pandemic have provided evidence of nurses’ psychological and physical distress during this time. The majority of the current research, however, consist of quantitative studies that measure mental health issues facing nurses at the point‐of‐service during COVID‐19 (e.g. Chen et al., 2020; Halcomb, McInnes, et al., 2020; Leng et al., 2020). Far fewer qualitative studies have been conducted to describe the experiences of these nurses (e.g. Halcomb, McInnes, et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020), and the studies are limited to specific groups, such as novice nurses (García‐Martín et al., 2020) or phenomenon such as professional identity (Sheng et al., 2020). There is a gap, therefore, in understanding the lived experiences of frontline nurses who care for patients with COVID‐19, particularly in adaptive and maladaptive coping with psychological traumas they have encountered.

This study's aim was to describe the lived experiences of nurses working in critical care areas that had previously been unexplored. We focused on responses surrounding traumatic experiences, alcohol and substance use, and mental health distress/well‐being. By describing the themes that emerge from the nurses’ responses, individual, professional and organizational strategies to mitigate and treat mental health issues will be more effective.

2. BACKGROUND

At the end of 2020, 2262 nurses in 52 countries had died from COVID‐19 and more than 1.6 million healthcare workers had been infected, and of this 1.6 million, nurses were the most impacted group in most countries (International Council of Nurses; ICN, 2021). The International Council of Nurses (2021) has projected a 10 million nurse shortfall by 2030 and this could be even further exacerbated by the ‘COVID‐19 effect’ causing nurses to be absent from work or leaving the profession all together. The high stress environment of caring for COVID‐19 patients has led nurses to have an increasingly negative view of the profession, which is causing an unwillingness to practice in the future (Cici & Yilmazel, 2021).

Contributing factors to nurse burnout include increases in mental health issues, experiencing trauma, and work‐related stressors (e.g. Chen et al., 2020; Halcomb, McInnes, et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020). Nurses have reported increases in moderate/severe anxiety and depression (43% and 26%, respectively) since the pandemic started (Kim et al., 2020). This includes significant levels of psychological distress (41%) and dysfunctional anxiety (38%) (Labrague & Santos, 2020; Shahrour & Dardas, 2020). These high stress environments appear to cause more psychological distress in younger versus older nurses (Shahrour & Dardas, 2020). This finding could be because most current studies have been done in novice nurses (García‐Martín et al., 2020).

Many nurses have expressed concerns that they will expose their family and significant others to COVID‐19 due to their work environment (García‐Martín et al., 2020; Halcomb, McInnes, et al., 2020; Master et al., 2020). This could be related to the issue of lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) at many facilities (García‐Martín et al., 2020; Halcomb, Williams, et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020). In one instance, 77% of nurses identified a need for better access to PPE (Halcomb, Williams, et al., 2020). In addition to the lack of PPE, nurses have also expressed a lack of support from their employers (García‐Martín et al., 2020; Halcomb, McInnes, et al., 2020). Only 55% of nurses stated they felt well supported by their employer (Halcomb, McInnes, et al., 2020).

All these factors combined have led nurses to feel there has been a decline in the quality of their patient care (Halcomb, McInnes, et al., 2020; Sheng et al., 2020). In a study of 637 nurses in Australia, Halcomb, McInnes, et al. (2020a) found that 34% of nurses perceived the care they were providing as slightly or significantly worse than before the pandemic.

Another factor contributing to nurses’ experiences with COVID‐19 patient care is the psychological traumas they experience. Chen et al. (2020) surveyed approximately 12,600 nurses and found 13% had experienced psychological trauma. With about 50% of these nurses working in COVID‐19‐designated hospitals, they found reports of traumatic experiences were higher in women, critical care units, and COVID‐19‐related departments (Chen et al., 2020). These traumatic experiences may be related to work factors such as the risk of infecting loved ones, lack of organizational support and decreased ability to provide adequate patient care (García‐Martín et al., 2020; Halcomb, McInnes, et al., 2020; Sheng et al., 2020). Knowing the high stress situations, nurses are facing due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, it is important to explore their perceptions to these events and how they are coping.

As stressors increase, nurses seek out ways to cope. One maladaptive coping strategy is through the use of substances, including alcohol. A recent study conducted by Foli et al. (EPub, 2021) revealed that tobacco, alcohol and other substance use risk were associated with indicators of psychological trauma. Measures of psychological trauma that were associated with risk of tobacco, alcohol and other substance use were: life events (alcohol and other substances), adverse childhood experiences (tobacco and other substance use) and indicators of lateral violence in the workplace (tobacco, alcohol and other substances) (Foli et al., 2021).

Recent literature, albeit pre‐pandemic, describing nurses’ substance use has been through a critical lens of the high‐pressured, high‐stakes environments in which nurses work, certainly amplified during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The work of Ross and colleagues (Ross, Berry, et al., 2018, Ross et al., 2019; Ross, Jakubec, et al., 2018) speaks to how discourses have framed the approach to nurses with substance use issues, approaches that employ individual culpability that ignore broader factors impacting nurses’ well‐being. Kunyk et al. (2016) echo an informed approach to nurses’ substance use that includes contextualizing the work environment stressors faced by nurses such as higher patient acuities and budget cuts. The findings from the current study will aid in understanding the nurses’ experiences, the use of substances, as well as successful and unsuccessful ways of coping during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

2.1. Theoretical framework: Nurses’ psychological trauma

A middle‐range theory of nurses’ psychological trauma provided our theoretical framework (Foli & Thompson, 2019). This theory describes the humankind and nurse‐specific traumas that are endured by nurses at the individual, professional and organizational levels (Foli, in press; Foli & Thompson, 2019). Nurse‐specific traumas are viewed as either avoidable or unavoidable and include (1) vicarious and secondary trauma, (2) historical and intergenerational trauma, (3) workplace violence, (4) system/medically induced trauma, (5) insufficient resource trauma, (6) second‐victim trauma and (7) trauma from disaster (Foli et al., 2020; Foli & Thompson, 2019). In this theory, nurses experience trauma as they render care as professional nurses (unavoidable) and as human beings who may have encountered traumatic events (unavoidable). Yet, there are some traumas at the professional and organizational levels that are avoidable, such as insufficient resource trauma, which are under the control of leaders in organizations. Insufficient resource trauma occurs when there is a lack of nursing staff, healthcare professionals, supplies, knowledge and other resources that are needed to render quality care (Foli et al., 2020). Although this theory was conceptualized pre‐COVID‐19 pandemic, the nurse‐specific traumas have intensified in the midst of this disaster.

Several outcomes are possible as nurses are faced with psychological trauma, both positive and negative. Positive outcomes include increased individual resiliency, posttraumatic growth, delivering and receiving trauma‐informed care, and system/organizational recognition of nurses’ trauma and praxis. The theory also describes negative outcomes from nurses’ continual traumatic experiences: staff turnover or nurses electing to leave the profession and mental health issues, including substance use (Foli, in press; Foli & Thompson, 2019; Foli et al., 2021). Each of these positive and negative outcomes represent the nurses’ attempts to cope with psychological trauma.

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Aims

The aim of this research study was to describe the experiences of frontline nurses who are working in critical care areas during the COVID‐19 pandemic with a focus on trauma and the use of substances as a coping mechanism. Nurses’ descriptions stemmed from two open‐ended items: ‘Please add any additional comments related to personal or professional trauma you have experienced’; and ‘Given the context of the pandemic, please add comments related to substance or alcohol use, or other mental health issues you have experienced, or witnessed in nurses’.

From these items, our research questions related to trauma were: What are the psychological traumas of nurses, who are working in critical care areas during the COVID‐19 pandemic? What are the themes and patterns of trauma, and do they support the theory of nurses’ psychological trauma? Our research questions related to substance use and mental health were: How has the pandemic affected critical care area nurses’ alcohol and substance use? What are nurses witnessing in terms of substance use and mental health in their peers and teams?

3.2. Design

The study design utilized an online survey platform, Qualtrics, to capture data. We believed that the Internet‐based data collection strategy provided privacy to nurses who expressed sensitive information surrounding trauma, substance use and mental health issues. This also afforded the opportunity for nurses to respond at their convenience. The research team believed a descriptive content analysis approach would be appropriate given the cross‐sectional data collected through an online survey. While contextual information was available based on the data, it limited our analysis to description. For example, the online qualitative data collection methodology did not allow follow‐up inquires or clarifications or an in depth understanding of the nurses’ working conditions that interviews or observations would have offered. Quantitative results will be reported elsewhere. Standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR; O’Brien et al., 2014) were used for this study.

The study survey was launched in June 2020 and was closed to enrolment in September 2020. During this time, COVID‐19 cases and deaths skyrocketed in the United States: 2,383,863 to 6,949,391 cases, and 122,436 to 203,191 deaths from 24 June 2020 to 23 September 2020, respectively (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021, April 22).

3.3. Sample/Participants

The sample consisted of registered nurses who were at the point‐of‐service during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Specific inclusion criteria were nurses who worked in critical care areas or had recent experience in critical care areas during the pandemic. One hundred and thirty‐seven nurses entered the online survey; however, due to those exiting prior to consent or before any questions were responded to, our final sample was 105 nurses. Of these 105 nurses, 55 nurses resided in the Midwest (38 in Indiana), 25 in the South, 14 in the West, 6 in the Northeast and 5 in Canada.

3.4. Data collection

Data were collected from mid‐June 2020 to early September 2020 via an online survey. Nurses were recruited through the research webpage of the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN) as well as an alumni list from a large, public Midwest university. A brief one‐paragraph overview of the study was posted by the AACN on the organization's designated research study page with a link to the Qualtrics survey. Alumni members were recruited through an email solicitation also with an embedded link to the survey. Responses to two open‐ended questions were analysed: ‘Please add any additional comments related to personal or professional trauma you have experienced’ (70 nurses contributed comments); and ‘Given the context of the pandemic, please add comments related to substance or alcohol use, or other mental health issues you have experienced or witnessed in nurses’ (65 nurses contributed comments). Responses varied in length from single sentences and phrases to lengthy paragraphs and half pages of single‐spaced text. Data from the quantitative surveys and computer‐based tasks are currently being analysed as parts of the larger parent study (N = 105), which examines nurses’ cognitive control behaviours, substance use and psychological trauma. For completion of the survey items, nurses were sent an electronic Amazon gift card code for $30.00.

3.5. Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Purdue University institutional review board (IRB‐2020‐751). Consent was obtained as nurses were instructed to review the full informed consent document that was embedded in the online survey prior to questions being asked. The survey contained both quantitative items and scales, as well as the two‐open ended questions. If they chose to participate, nurses were then instructed to click a radio button immediately following the informed consent document. This indication was required prior to moving forward in the survey. Undocumented consent was approved by the ethics board to capture candid reports of both trauma and substance use. The participant could also exit the survey at any time or skip a question that made them uncomfortable or that they preferred not to answer. Investigators’ contact information was available in recruitment and consent documents.

3.6. Data analysis

We used content analysis to understand the respondents’ thoughts and perceptions of their experiences related to COVID‐19 in alignment with furthering understanding of individuals’ meanings and context (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). The three phases of analysis used were (1) preparation, (2) organization and (3) reporting (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). During the preparation stage, the researchers agreed the unit of analysis (the word/theme to be derived) would be any text related to nurses’ experiences with COVID‐19 and any text related to coping mechanisms (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). An inductive approach was used, which allowed the derived themes to appear naturally from the data (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Two coders reviewed the data to extract themes using the approach outlined by Elo and Kyngäs (2008; DeSantis & Ugarriza, 2000; Elo et al., 2014).

Each reviewer open‐coded the data independently, taking notes of the text while reading. After the first read, each reviewer compiled their notes into freely generated categories. Once both reviewers had completed their independent reviews, they came together to compare the created categories for similarities and differences. The categories were further sub‐divided or combined to create the overall themes of the data. All derived themes meet the four criteria outlined by DeSantis and Ugarriza (2000): (1) emerge from the data, (2) are abstract in nature, (3) are iterative and (4) occur at many levels. Quotations (i.e. authentic citations) are provided in the findings section to further enhance the trustworthiness of the study and are unedited (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008).

3.7. Validity and reliability/rigour

Rigour in the study surrounds trustworthiness. Components of trustworthiness are credibility, dependability, conformability, transferability and authenticity (Elo et al., 2014). Results are considered trustworthy when they have conformability and transferability (Elo et al., 2014). The data presented from this study shows conformability because it represents the original thoughts and experiences of nurses from a broad range of practice areas/locations and was not created by the researchers (Elo et al., 2014). Additionally, the data are transferable to nurses across the United States and beyond who have experienced work‐related trauma during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Elo et al., 2014). The data are also potentially transferable to other healthcare workers. Finally, quotations from participants have been provided for each theme to further enhance the trustworthiness of the results (Elo et al., 2014).

4. FINDINGS

4.1. Comparison analysis results

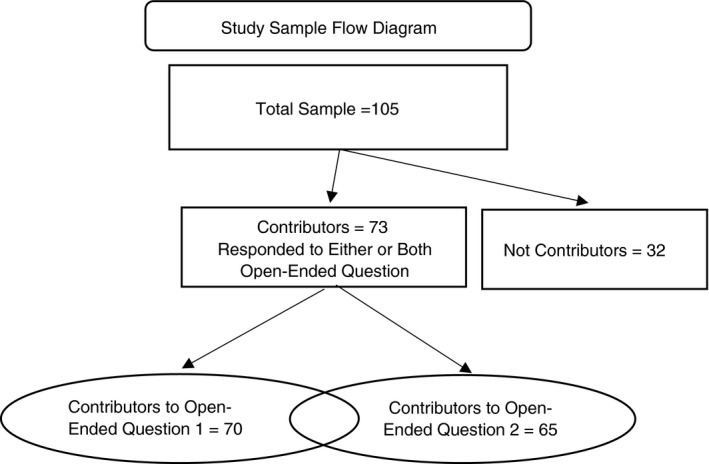

Seventy‐three nurses contributed to either or both open‐ended questions (70 nurses contributed to Question 1 and 65 nurses contributed to Question 2; See Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study sample flow diagram

The 73 nurses were approximately 35 years of age, overwhelmingly female, typically married or living with someone as if married, Caucasian, and had been licensed as a registered nurse for an average of 12 years (Table 1). We compared reports between the nurses who completed either or both of the open‐ended responses and those who did not. No differences were noted on these demographic items.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of nurses who did and did not contribute open‐ended responses: Demographic, trauma and substance use variablesa

| Variable | Overall |

Not‐Contributor (n (%)) |

Contributor (n (%)) |

p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | n = 32 | n = 73 | ||

| Gender (n = 105) | 0.9 | |||

| Male | 3 (2.9) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Female | 102 (97.1) | 31 (97.0) | 71 (97.0) | |

| Age (years), Mean (SD) (n = 103) | 34 (11.0) | 33 (10.4) | 35 (11.3) | 0.4 |

| Marital Status (n = 105) | 0.7 | |||

| Divorced | 3 (2.9) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Living with someone as if married | 13 (12.4) | 2 (6.2) | 11 (15.0) | |

| Married | 48 (45.7) | 16 (50.0) | 32 (44.0) | |

| Never married | 39 (37.1) | 12 (38.0) | 27 (37.0) | |

| Widowed | 2 (1.9) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Race/Ethnicity (n = 105) | 0.2 | |||

| African/Black American | 6 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (8.2) | |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 1 (1.0) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Bi‐racial or multi‐racial | 4 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.5) | |

| Caucasian or White American | 87 (82.9) | 29 (91.0) | 58 (79.0) | |

| Hispanic American | 2 (1.9) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Other | 4 (3.8) | 1 (3.1) | 3 (4.1) | |

|

Year Since Initial License, Mean (SD) (n = 101) |

11 (10.4) | 10 (10.5) | 12 (10.4) | 0.5 |

| Trauma Variables | ||||

| Life Events (n = 94) | n = 21 | n = 73 | 0.9 | |

| Does not apply | 3 (3.2) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (2.7) | |

| Happened to me | 18 (19.1) | 4 (19.0) | 14 (19.0) | |

| Part of my job | 69 (73.4) | 15 (71.0) | 54 (74.0) | |

| Witnessed it | 4 (4.3) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (4.1) | |

| Unknown | 11 (11.7) | 11 (52.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ACE Score, Mean (SD) (n = 88) | 1.39 (1.8) | 0.35 (0.9) | 1.69 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| PTSD, Mean (SD) (n = 96) | 2.56 (1.5) | 2.17 (1.5) | 2.69 (1.5) | 0.11 |

| Substance Use Variables | ||||

| AUDIT, Mean (SD) (n = 86) | 4.5 (4.3) | 5.3 (4.5) | 4.3 (4.3) | 0.5 |

| DAST−10, Mean (SD) (n = 88) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.2 |

ACE = adverse childhood experiences; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; DAST‐10 = Drug Abuse Screening Test; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Note: Includes nurses who contributed to any of the open‐ended items, except for participants 146, 152, 153 and 154 due to missing survey data. The qualitative data offered by these participants is included in the Findings section.

To assess for potential differences between nurses who forwarded comments compared with those who did not, we collected measures of psychological trauma and alcohol and drug use. Three scales were used to measure for trauma: The Life Event Checklist for DSM‐5 (LEC‐5) to report traumatic life events (Blake et al., 1995; Weathers et al., 2013), 10‐items related to adverse childhood experiences (ACE; Felitti et al., 1998), and the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM‐5 as a proxy for nurses’ symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (Prins et al., 2015). Differences were noted in that those who contributed open‐ended responses reported higher ACE scores (0.35 versus 1.69; <0.001). To ensure that the contributor sample did not differ in alcohol and substance use, we also compared self‐reports of alcohol use through the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) and drug use through the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Yudko et al., 2007); no differences between the groups were found (Table 1).

4.2. Nurses’ psychological trauma

Five major themes were derived from the responses about psychological traumas the nurses had experienced (see Table 2). In the first theme, nurses’ descriptions indicated ‘psychological distress in multiple forms, including anxiety, depression, guilt and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)’. This theme supports the multiple types of nurse‐specific and nurse‐patient‐specific traumas facing critical care nurses at the bedside during the pandemic. Depression, PTSD, anxiety and guilt were repeatedly cited as psychological distress was described.

The hardest thing I have seen was when we ran out of body bags and had to tie trash bags around our dead patients heads, tie their hands and feet with tape, and wrap them in a sheet. This keeps coming back to me repeatedly (Participant 41).

TABLE 2.

Themes and subthemes: Nurses’ psychological trauma and the marathon of crisis

|

Theme #1: Psychological distress in multiple forms: Including anxiety, depression, guilt and symptoms of PTSD |

Subtheme: New and increasing mental health issues Subtheme: Exacerbation of existing mental health issues |

|

Theme #2: Tsunami of Death: Overwhelming grief and loss |

Subtheme: These deaths are different: dying alone |

|

Theme #3: Torn between two masters: Personal/family safety and professional duties |

Subtheme: Nurses as victims: Exposed to and sick with COVID−19 Subtheme: Living vector/endangering family |

|

Theme #4: Betrayal: Professional disillusionment, job dissatisfaction and intention to leave job/profession |

Subtheme: Organizational betrayal Subtheme: Constant changing guidance Subtheme: Public ignorance |

|

Theme #5: Resiliency/posttraumatic growth through self and others: Professional experiences and other sources |

Subtheme: Sources of resiliency: experience and exposure to positive significant others (e.g. parents, peers and friends) |

One nurse confessed to ‘feeling numb’ (Participant 130) due to the conditions at work and in the community, which is common with compassion fatigue.

All seven types of nurse‐specific traumas (Foli, in press; Foli et al., 2020; Foli & Thompson, 2019) were supported in the nurses’ statements, particularly insufficient resource trauma: ‘I feel I have limited time to spend in my patients room doing patient care…’ (Participant 152); ‘We have equipment, staff, and PPE shortages’ (Participant 63). Vicarious and secondary trauma were also frequently described: ‘The deaths were so sad the worst was not letting families come see them before they die’ (Participant 154), and ‘Taking care of my first pregnant COVID‐19 patient who had to deliver her baby alone and had to be separated from her baby immediately after birth was more traumatizing than I realized’ (Participant 49). Historical trauma in the context of nurses as an oppressed group was also reported: ‘I feel taken advantage of by my unit and my hospital system‐they are expecting too much, I am exhausted’ (Participant 88). Second‐victim trauma was also reported: ‘…recently made an error at work which devastated me…’ (Participant 107).

The moral distress as nurses work amid a disaster was also described. Making ‘tough care decisions’ (Participant 32) during disasters while working with inadequate supplies and personnel created psychological trauma that lingered with nurses. Thus, trauma faced during the natural disaster of COVID‐19 recurred in the text: ‘The conditions under which we are working… are horrifying’ (Participant 88) and ‘It was traumatic seeing patients being taken of dialysis machines so that others can use them because we were short with supplies’ (Participant 19). Patients undergoing treatments also aligned with system/medically induced trauma: ‘…reliving the deaths of patients from the first surge (people we took care of for months)…’ (Participant 67). Last, trauma associated with workplace violence was also described: ‘On a few occurrences I can recall, a family became verbally aggressive and abusive to myself as charge and the patients bedside nurse’ (Participant 20).

Nurses reported beliefs that the care they are providing is inadequate with feelings of isolation from their friends/family due to their job, both contributing to the manifestation of psychological distress during this time period.

This is unprecedented, and my family is my support system, but my family doesn't want to see me because of concern for exposure. While I understand and would never want to willingly expose them, I am hurting emotionally. I have never felt more alone, more isolated (Participant 45).

Subthemes arose organically from the data and reflect the influence of the pandemic on mental well‐being. The subtheme, “new and increasing mental health issues” was exemplified by a nurse commenting: “I feel numb most of the days because I feel like things are just getting worse instead of better at work and in my community” (Participant 130). A second subtheme, ‘exacerbation of existing mental health issues’ was represented by the following: “I had PTSD, anxiety and depression prior to the pandemic. Things during the episode do seem to have added to it” (Participant 153).

The second theme, ‘tsunami of death: overwhelming grief and loss’, is induced by the numbers of patients who passed due to COVID‐19. Nurses working in COVID‐19 units were experiencing higher numbers of patient deaths along with feelings of inadequate care provision. While nurses experience patient loss at some point during their careers, the COVID‐19 pandemic brought this experience to the foreground. Nurses were also dealing with grief and loss in their personal lives due to loss of family and friends, and such bereavement may have been exacerbated by their experiences at work. A subtheme also emerged that conveys how these deaths were distinct from the pre‐pandemic world of nursing care: ‘these deaths are different: dying alone’. The patients are isolated, without family, and the nurses describe the burden of how the patient deaths are unique in their aloneness:

…I have seen so much suffering and death, I have had to facetime families on a small ipad to let them tell their loved one goodbye before compassionately extubating patients. I have been the only one in the room when a person has passed away… (Participant 88).

The third theme, ‘torn between two masters: personal/family safety and their professional duties’, also reflected psychological distress and trauma. The nurses working during COVID‐19 felt the strain of wanting to provide quality care but having to consider the impact their professional positions place on their home/family life. This placed them in a difficult situation because they wanted to provide care, but they also want to keep their families safe. This led to role and identity tension for the nurse as well. They were striving to offer care and comfort while faced with unprecedented circumstances:

The deaths were so sad the worst was not letting families come see them before they die. Nurses feel they need to be the person to be by their side all the time if the pt is going to doe‐ we don't let people die alone ever! (Note: unedited text) (Participant 154).

Several nurses described contracting the virus and becoming ill, reflected in the subtheme: ‘nurses as victims: exposed to and sick with COVID‐19’:

We experienced PPE shortages in March, and by the 2nd week of March I showed symptoms of COVID and tested positive. I was out of work for 32 days recovering. I experienced quite a bit of loneliness, isolation, fear, and anxiety while I was sick (Participant 63).

Becoming a ‘living vector/endangering family’ was another subtheme. They faced the burden of putting themselves and their families at significant risk by being the point of contact with patients diagnosed with COVID‐19.

…being thrown into a pandemic patient room with little or not enough PPE. and advised that this is all we have. being concerned about taking the virus home to my family and having no support from administration and no communication from them (Participant 114).

Nurses also forwarded decreased support from family and friends who were fearful of contracting the COVID virus from the nurse, thereby increasing the psychological distress of the nurse.

The fourth theme was based on the repeated narratives that described ‘betrayal: professional disillusionment, job dissatisfaction, and intention to leave their job/profession’. Feelings of being betrayed stemmed from organizational use of nurses, constant changing guidance related to caregiving practices, and public ignorance. In the following text, one nurse equated the nurse to an anonymized body, a tool of the hospital to provide care to inpatients in the subtheme, ‘organizational betrayal’.

Concern about infecting family and friends. the hospitals want bodies to take care of patients. What about the nurses we want to live also (Participant 53).

Nurses felt betrayed when their organization did not support them through sufficient personal protective equipment, consistent guidance, and managerial support. The extra strain from these conditions drove nurses to secure positions away from critical care/the bedside or exit the nursing profession all together. The description of working conditions indicates that such environments were unsustainable, as supported by the desire to leave nursing, including ‘selling insurance from home’ (Participant 23). One nurse described her betrayal:

…I have worked for 14 hours without eating or using the restroom. I have had recurrent urinary tract infections because I have not had enough time during the day to simply go to the bathroom or drink water. The conditions under which we are working, at one of the most well‐known and well‐respected hospitals in the country is horrifying. It has made me want to leave the healthcare profession altogether (Participant 88).

Accounts of frequent changes in unit protocols and frustration surrounding public ignorance of the reality of the pandemic were also expressed. ‘Constant changing guidance’ related to patient care was another subtheme captured by comments such as: ‘I am an emergency department RN and we have had to deal with constant change, sometimes on a daily basis about how to care for our patients’ (Participant 50). Nurses were incensed over the lack of public support and indeed, by our subtheme, ‘public ignorance’. One nurse stated: ‘I have become very disheartened at the amount of selfishness, hatred, anger and defiance associated with the general public and with many friends during the course of the pandemic’ (Participant 68).

The fifth theme emerged as nurses described an ability to overcome trauma through ‘resiliency/posttraumatic growth through self and others; professional experiences and other sources’ as potential buffers to trauma. Amid the negativity brought on by the pandemic, there were signs of resiliency in nurses. Some narratives reflected self‐care behaviours, the benefit of prior experiences, and support from their co‐workers, family and friends. Many of the nurses stated how they drew on past exposures to trauma and coping mechanisms to help them navigate the burden of working during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

I don't really feel I have experienced any trauma due to Covid. I have been a nurse for so long, and have had so many life experiences that I feel have prepared me for this particular time in my career. I was there for the beginning of HIV, Toxic Shock, Legionaires, H1N1 and so many other diseases, that I almost felt immune. Not in a foolish way, just that with good PPE & nursing practices, I would be O.K. I took practical actions to protect my family from any 2nd hand exposure… I've had friends die young from diseases that are now almost completely curable, I've had friends murdered and killed in action young, so I know a long life is not guaranteed. Bad things happen to the nicest of people, and bad people often get the best of breaks. Through my own traumatic experiences, I've learned that I can rise above it. I've tried to share this perspective of hope with my younger colleagues (Participant 146).

The nurse described being able to bounce back in the face of adversity and transcendence above the trauma. Additional buffers that were forwarded included being raised by competent, positive parents, and team members who were ‘amazing’ (Participant 48) and willing to help each other through shared experiences, which supported our subtheme: ‘sources of resiliency: experience and exposure to positive significant others (e.g. parents, peers, and friends)’.

4.3. Nurses’ substance/alcohol use and mental health distress

In the second open‐ended question, nurses forwarded responses to: ‘Given the context of the pandemic, please add comments related to substance or alcohol use, or other mental health issues that you have experienced, or witnessed in nurses’. Three themes were revealed in our analysis. The first theme, ‘mental health crisis NOW!!!: “more stressed than ever, and stretched thinner than ever’”, represents a pattern to the narratives that describes an urgent mental health crisis with nurses (see Table 3). Nurses described being changed, as if something inside them has been lost in our subtheme: ‘unusual times: “forever changed” due to the pandemic’. There is a general sense of exhaustion: ‘In the beginning of the pandemic, we were considered heroes and morale was great, but now in general, the nurses I work with are stressed and burnt out’ (Participant 25). These extreme circumstances left them struggling with increased mental health issues, mixed emotions about the profession overall, and exhausted. An inability to cope with the unusual stress and trauma resulted in using alcohol for this nurse:

My mental health has never been worse. I know this is true for other nurses as well as the general public. I feel that I need some sort of outlet for my anxiety and depression but don’t know what will help. Many people I know turn to substances like alcohol. It is especially hard as a new nurse in a new city since I do not have the connections or support I feel that I need (Participant 126).

TABLE 3.

Themes and subthemes of nurses’ substance use and mental health distress

|

Theme #1: Mental health crisis NOW!!: ‘more stressed than ever, and stretched thinner than ever’ |

Subtheme: Unusual times: ‘forever changed’ due to pandemic |

|

Theme #2: Turning to substances to cope: Alcohol, food, tobacco/smoking, recreational drugs/marijuana |

Subtheme: Normalizing use of substances through check‐ins and talking about increased use Subtheme: Coping with alcohol: Backing away versus questioning dependency |

|

Theme #3: Where is the support? |

Subtheme: Less peer and family support/isolation |

One individual categorized nurses into groups based on their ability to cope with their mental health distress:

Also, I have noticed there are 2 types of nurses in respect to the pandemic. One being carefree and sometimes dangerous in their complacency towards policy/personal protection. The other, Nervous, double masking, surgical hats stating coronavirus can attach itself to hair (false!!), continually checking world health‐o‐meter statistics… It’s a balancing act knowing what is normal to feel and when does one seek professional help.. (Participant 107).

These two behavioural extremes reflect the profound mental health crisis caused by the pandemic for practicing nurses. The struggle to maintain a life outside of work was also be seen. One nurse described how she pretended to relax ‘at a resort with a cocktail’ (Participant 29) in her backyard to try and enjoy life. Those considered ‘strong’ are now vulnerable: ‘I have seen some of the strongest, most experienced nurses on our unit break down and have panic attacks to the point where they have had to be sent home’ (Participant 88). One nurse described how this erosion of mental wellbeing due to the longevity of the pandemic had changed them: ‘I haven't really seen any substance abuse issues, but I have seen the mental health effects on nurses & other staff. The hopelessness, futility, and pain at not being able to save everyone, especially the young ones with families’ (Participant 146).

The second theme, ‘turning to substances to cope: alcohol, food, tobacco/smoking, recreational drugs/marijuana’, is related to nurses continuing attempts to cope with the ravages of the pandemic. While alcohol was the most prevalent, they reported using recreational drugs, such as marijuana, as well as tobacco: ‘I know of several nurses that are drinking alcohol more or using drugs recreationally in association with the pandemic’ (Participant 68). Others stated their food consumption patterns changed or they turned to food as a coping mechanism.

Our first subtheme was related to increased substance use: ‘normalizing the use of substances through check‐ins and talking about increased use’. By checking in with each other, they felt less alone and were reassured that others were coping in the same ways. The narratives also showed that nurses were more open to discussing their alcohol use than they were in the past. Now that COVID‐19 provided them with a reason to drink more, they were more willing to openly talk about it: ‘I have noticed that nurses are much more open about their drinking/stress reliving habits as if to receive approval from their peers’ (Participant 99), and ‘It seems as if daily drinking has been normalized among employees’ (Participant 61).

Some nurses unapologetically reported increase alcohol use, while others became self‐aware of the pattern of alcohol intake, became concerned, and were able to decrease consumption. The following narrative exemplifies the subtheme: ‘coping with alcohol: backing away vs. questioning dependency’:

Many co‐workers of mine had resorted to alcohol as a way to cope with the encounters we see daily at work. I drink very sparingly d/t a family history of alcoholism so I am thankful I have not succumbed to the temptation (Participant 109).

Nurses purposefully decreased alcohol intake for additional reasons, including ‘health reasons’ (Participant 26), fear of dependency, and to ‘keep immune system up’ (Participant 50). Others questioned whether their alcohol intake and their peers’ intake had become problematic.

The third theme, ‘Where's the support?’, describes the overall lack of support, weakened coping mechanisms and the increased maladaptive coping mechanisms, which changed in nurses as a result of the pandemic. Throughout the pandemic, nurses turned to different types of support systems for coping with these traumatic experiences. As discussed, many turned to substance use, primarily alcohol, as a new coping mechanism. As exhaustion and mental health distress was endured, peers had less reserves to offer their fellow nurses. Previous peer support on the unit decreased due to the increased needs of the patients and the burden shared by the unit nursing staff. Nurses reported having to find new ways of coping or alter their pre‐existing systems to psychologically handle the stress of the ongoing pandemic. The subtheme, ‘less peer and family support/isolation’, is expressed by the nurse's narrative:

We are all on edge, and do not have the social support from each other that we used to have. Remaining isolated from each other and not having the opportunity to “vent” or commiserate, or even give and get a hug is traumatic. We spend more awake time together than with our families and we have lost the ability to give and get the support we are used to on the floor (Participant 18).

Nurses worked together to render care; however, due to the infectious nature of the COVID‐19 virus, there was physical isolation and emotional isolation at work, at home, and in the community. Through maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as increased alcohol intake, nurses attempted to endure. It is of note that some nurses have maintained or attempted to maintain their mental and physical health in purposeful and thoughtful ways:

I fortunately don't have issues with substance abuse. I take care of my mental health as best I can by staying healthy and taking supplements to keep my stress levels in check. I exercise regularly because that has always been my go to self‐care activity. But even with all the things I do to keep physically and mentally healthy, I still find myself unmotivated, overwhelmed, and frustrated because I feel I don't have the energy and mental clarity to do the things I want to do like working on getting into graduate school… (Participant 130).

Taken as a whole, responses to the question surrounding substance use and mental health reveal nurses’ intake of substances, especially alcohol has increased. Mental health issues such as depression, anxiety and exhaustion have set in: ‘Burn out. Nurse, including myself, feel drained and run down at the end of shifts. At times, you lose hope in your skills and the outcome of patient care’ (Participant 118). The ability to cope has been weakened with concurrent weakening of support systems, especially from peers.

4.4. The marathon of crisis

While a lengthy narrative, we believe this text signifies the traumatic experiences of many of the nurses and moves beyond the themes to fully articulate an overarching theme, ‘the marathon of the crisis’, that arose from the data. Trauma is not experienced in one day, but many days with seemingly endless days to come. The description of PTSD‐like symptoms at the end is of note as this nurse describes the marathon of crisis.

At the start of the pandemic, I was asked to help at a sister hospital in (BLINDED CITY) that was overwhelmed with COVID‐19 patients. The hospital did not have enough critically care trained nurses to care for the amount of patients we were seeing. I agreed to help, despite the fact that I had a 6 month old at home. My very first shift at the sister hospital, I had 3 intubated, sedated, paralyzed, proned, unstable patients. My "help" for the shift was a pediatric nurse who had no experience in ICU, much less an adult ICU of this caliber. The pediatric nurse was extremely uncomfortable which left me to do the majority of the work myself. I wore my N‐95 mask for the entire 13 hour shift. I would often times be in a patient's room for over 1 hour at a time, trying to cluster my care as much as possible to reduce exposure. This made it difficult to monitor my other two patients, so I often had my pediatric nurse watch the monitors and notify me of any changes. We had made it through 3/4 of the shift and I was doffing my PPE from one of my patient's rooms and I hear a CODE BLUE being called overhead. It was my other patient. I quickly donned new PPE and ran into his room. The patient was proned and had to be supinated before I was able to start chest compressions. No one wanted to enter the room to help due to the risk of exposure. The individuals in the room consisted of myself, the RT, the pediatric nurse, and the unit charge RN. We quickly supinated the patient and began ACLS protocol. The doctor refused to enter the room and other nurses would hand medications in through the door. We coded the patient for approximately 45 minutes before being forced to call TOD. The patient was 52 years old… and I had just gotten off the phone with his daughter a few hours prior stating he was critical but stable and now he was deceased. That next shift, I came back and had a similar group of patients. Approximately 5 hours into the shift, a co‐works patient coded and died as well. He was 37. I often replay these scenarios in my head and think about these patients and the care we provided to them and wonder what more we could have done. That was 6 months ago. I currently suffer from night terrors according to my fiancé and have experience extreme anxiety and depression. I currently see a therapist and have made an appointment to be evaluated for medication to ease my anxiety and depression (Participant 109).

The nurses conveyed in vivid detail the lived experiences of the nurse in critical care areas during the COVID‐19 pandemic. They appeared eager to share, eager to have a voice communicate what they have lost, what they were experiencing and more than that, how these losses and experiences had affected them.

5. DISCUSSION

The narratives shared by nurses convey the extreme emotional distress they are experiencing while working during the COVID‐19 pandemic. In our first open‐ended question asking for nurses’ self‐reports of personal or professional trauma, we found evidence to support the middle‐range theory of nurses’ psychological trauma (Foli, in press; Foli et al., 2020; Foli & Thompson, 2019). Several nurse‐specific traumas were described, including secondary trauma (e.g. overwhelming grief and loss), workplace violence (e.g. angry/aggressive families), system/medically induced trauma (e.g. ventilated patients who are isolated), insufficient resource trauma (e.g. endangering family due to lack of PPE; lack of staff), second‐victim trauma (e.g. medical errors), historical trauma (e.g. betrayal and using nurses as ‘bodies’), and trauma from disaster (e.g. these deaths are different, rationing equipment). The avoidable traumas that rest primarily with the organization may result in nurses leaving the profession, increased substance use, continued psychological distress as well as, in select cases, posttraumatic growth. There were also narratives that reflected the hardships which insufficient resources induced. Across the globe nurses are forced to make difficult decisions surrounding patient care during this natural disaster, and international studies support similar findings in the United States (Gunawan et al., 2021; Halcomb, Williams, et al., 2020; Sheng et al., 2020). Tough patient care decisions may be further exacerbating the traumatic responses nurse are experiencing.

Specifically, nurses’ narratives highlight our first theme to open‐ended question one: ‘psychological distress in multiple forms’, including anxiety, depression, guilt and traumatic events. Their experiences are similar to those of nurses globally who are caring for individuals during the COVID‐19 pandemic (e.g. Gunawan et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2020; Labrague & Santos, 2020). Theme 2, ‘tsunami of death’, in which nurses’ narratives described the volume of deaths as well as how patients passed alone without families or friends. The nurses were often the patients’ only point of contact and support. As previously presented (see Study Design), COVID‐19 cases and deaths rose dramatically during the time the study was open to enrollment (e.g. an increase of over 80,000 deaths).

Theme 3, ‘torn between two masters’ was supported as nurses expressed the fear they felt when thinking about possibly exposing their family and significant others to COVID‐19. They were emotionally divided between their professional responsibilities and being able to protect their families from potential exposure to the virus. The narratives detailing fear and anxiety also align with published accounts, especially among new nurses, who are concerned about becoming vectors of COVID‐19 (García‐Martín et al., 2020).

Theme 4, ‘betrayal’, specifically, nurses feeling betrayed and used as bodies with insufficient resources, overlapped with many of the published accounts (e.g. Gunawan et al., 2021). Multiple factors appear to result in nurses’ considerations of leaving the profession. Many expressed feelings of job dissatisfaction and professional disillusionment, which led them to consider leaving bedside care and even nursing as a whole. These narratives are not surprising since previous research has highlighted that the positive perspective of the nursing profession has decreased from 63% to 51% since the start of the pandemic (Cici & Yilmazel, 2021).

The last theme associated with the first open‐ended question, ‘resiliency/posttraumatic growth through self and others’, was derived from the narratives, although this theme was represented by the fewest data. While acknowledging the possible traumatogenic aspects of the COVID‐19 pandemic, some argue for a salutogenic approach (Kalaitzaki et al., 2020; Olson et al., 2020). Emerging literature indicates that nurses and healthcare professionals working during the pandemic may experience posttraumatic growth (Chen et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Li et al. (2021) found that frontline nurses had higher posttraumatic growth self‐report scores than those not working on the frontlines of the pandemic; however, more research is needed.

In the second open‐ended question surrounding substance use and mental health, our first theme, ‘mental health crisis NOW!!’ and second theme, ‘turning to substances to cope’, align with large survey findings that tracked nurses’ mental health and substance use during the pandemic (ANA Enterprise, 2020a, 2020b). In the COVID‐19 Survey Series 1 and 2 (ANA Enterprise, 2020a, 2020b), mental health and wellness, 18% of 10,997 nurses who responded to the survey reported an increase in the use of alcohol over the past 2 weeks (20 March through 6 July 2020); this increased to 19% of the 12,881 nurses who responded to the second survey (4–30 December 2020). Other results are concerning as well. When asked to report symptoms of psychological distress in the past 14 days, nurses who felt anxious or unable to relax increased from 48% (survey 1) to 57% (survey 2), for depression from 28% (survey 1) to 38% (survey 2), for feeling isolated and lonely from 29% (survey 1) to 37% (survey 2) (ANA Enterprise, 2020a, 2020b).

Our third theme, ‘where is the support?’, was also reflected in the ANA Enterprise surveys (2020a, 2020b). Along with the mental exhaustion, nurses expressed the lack of support from their employers. They felt their organizations were unsupportive, either via a lack of PPE, managerial presence or consistent COVID‐19 regulations. Nurses across the world are experiencing these system failures (García‐Martín et al., 2020; Gunawan et al., 2021; Halcomb, McInnes, et al., 2020). Without the support of their organizations, nurses are not able to provide adequate care for themselves or patients. The ANA Enterprise surveys (2020a, 2020b) also asked about employer support. Nurses responded slightly less favourably as the pandemic unfolded to the question: ‘My employer values my mental health’, responding in the first survey with an average of 3.3 (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) to an average of 3.2 in the second survey (ANA Enterprise, 2020a, 2020b). Notable is the fact that the survey responses track nurses’ experiences through the pandemic as a ‘marathon of crisis’, and seem to reflect worsening psychological conditions for nurses.

Taken in total, the evidence amassed takes on an urgency for praxis. This evidence includes the current study, additional studies performed from multiple nations around the world, and the ANA Enterprise surveys (2020a, 2020b). Praxis includes both organization and federal levels of support (Dzau et al., 2020). However, the individual support at the point‐of‐service is warranted given the psychological distress that can be avoided. Providing concentrated efforts on nurse wellbeing, needed supplies, nursing professionals, other staff members who are available, and adequately oriented/prepared, will allow individuals the space to begin to process loss and build resilience.

5.1. Limitations

Limitations of the study include self‐select bias to the sample. Those nurses who may have been experiencing increased psychological distress may have been more inclined to respond to the survey. Additionally, those nurses who experienced higher adverse childhood events (ACEs) appear to have responded to the survey rather than those with lower ACE scores.

6. CONCLUSION

The evidence to support nurses’ psychological trauma and injury, exacerbated by the current pandemic, is overwhelming. Taken as a whole, nurses’ reports of psychological distress and trauma point to the need for nursing and healthcare leaders to take action to mitigate unavoidable and avoidable nurse‐specific traumas, such as insufficient resource trauma. Leaders should secure resources to provide mental health services to nurses in need. These mental health resources should include screening for PTSD, depression, anxiety, alcohol and substance use, as well as the provision of treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria: (1) Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.14988.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the nurses who participated in the study for giving their time and sharing their experiences.

Foli, K. J., Forster, A., Cheng, C., Zhang, L., & Chiu, Y.-C. (2021). Voices from the COVID‐19 frontline: Nurses’ trauma and coping. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77, 3853–3866. 10.1111/jan.14988

Funding information

This study was funded by the Health and Human Sciences (HHS) COVID‐19 Rapid Response Grant Program sponsored by Purdue University College of Health and Human Sciences, West Lafayette campus.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Blake, D. D., Weathers, F. W., Nagy, L. M., Kaloupek, D. G., Gusman, F. D., Charney, D. S., & Keane, T. M. (1995). The development of a Clinician‐Administered PTSD Scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(1), 75–90. https://doi‐org.ezproxy.lib.purdue.edu/ 10.1002/jts.2490080106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2021). Trends in number of COVID‐19 cases and deaths in the U.S. reported to CDC by state/territory. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid‐data‐tracker/#trends_dailytrendscases

- Chen, R., Sun, C., Chen, J.‐J., Jen, H.‐J., Kang, L. X., Kao, C.‐C., & Chou, K.‐R. (2020). A large‐scale survey on trauma, burnout, and posttraumatic growth among nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(1), 102–116. 10.1111/inm.12796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cici, R., & Yilmazel, G. (2021). Determination of anxiety levels and perspectives on the nursing profession among candidate nurses with relation to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57(1), 358–362. 10.1111/ppc.12601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis, L., & Ugarriza, D. N. (2000). The concept of theme as used in qualitative nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22(3), 351–372. 10.1177/019394590002200308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzau, V. J., Kirch, D., & Nasca, T. (2020). Preventing a parallel pandemic—a national strategy to protect clinicians’ well‐being. New England Journal of Medicine, 383, 513–515. 10.1056/NEJMp2011027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open, 4(1), 1–10. 10.1177/2158244014522633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANA Enterprise . (2020a). Pulse on the nation’s nurses COVID‐19 Survey Series: Mental health and wellness (Survey #1). https://www.nursingworld.org/practice‐policy/work‐environment/health‐safety/disaster‐preparedness/coronavirus/what‐you‐need‐to‐know/mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐survey/

- ANA Enterprise . (2020b). Pulse on the nation’s nurses COVID‐19 Survey Series: Mental health and wellbeing (Survey #2). https://www.nursingworld.org/practice‐policy/work‐environment/health‐safety/disaster‐preparedness/coronavirus/what‐you‐need‐to‐know/mental‐health‐and‐wellness‐survey‐2/

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foli, K. J. (in press). A middle‐range theory of nurses’ psychological trauma. Advances in Nursing Science. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foli, K. J., Reddick, B., Zhang, L., & Krcelich, K. (2020). Nurses’ psychological trauma: “They leave me lying awake at night”. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 34(3), 86–95. 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foli, K. J., & Thompson, J. R. (2019). The influence of psychological trauma in nursing. Sigma Theta Tau International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Foli, K. J., Zhang, L., & Reddick, B. (Epub 2021). Predictors of substance use in registered nurses: The role of psychological trauma. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 10.1177/0193945920987123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Martín, M., Roman, P., Rodriguez‐Arrastia, M., del Mar Diaz‐Cortes, M., Soriano‐Martin, P. J., & Ropero‐Padilla, C. (2020). Novice nurse’s transitioning to emergency nurse during COVID‐19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(2), 258–267. 10.1111/jonm.13148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, J., Aungsuroch, Y., Marzilli, C., Fisher, M. L., Nazliansyah, N., & Sukarna, A. (2021). A phenomenological study of the lived experience in the battle of COVID‐19. Nursing Outlook (in press). 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb, E., McInnes, S., Williams, A., Ashley, C., James, S., Fernandez, R., Stephen, C., & Calma, K. (2020). The experiences of primary healthcare nurses during COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 52(5), 553–563. 10.1111/jnu.12589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb, E., Williams, A., Ashley, C., McInnes, S., Stephen, C., Calma, K., & James, S. (2020). The support needs of Australian primary health care nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1553–1560. 10.1111/jonm.13108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses (ICN) . (2021). COVID‐19 update. International Council of Nurses. https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline‐files/ICN%20COVID19%20update%20report%20FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzaki, A. E., Tamiolaki, A., & Rovithis, M. (2020). The healthcare professionals amidst COVID‐19 pandemic: A perspective of resilience and posttraumatic growth (Letter to the Editor). Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 102171. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. C., Quiban, C. A., Sloan, C., & Montejano, A. (2020). Predictors of poor mental health among nurses during COVID‐19 pandemic. Nursing Open, 8, 900–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunyk, D., Milner, M., & Alissa Overend, A. (2016). Disciplining virtue: Investigating the discourses of opioid addiction in nursing. Nursing Inquiry, 23, 315–326. 10.1111/nin.12144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague, L. J., & Santos, J. A. A. (2020). COVID‐19 anxiety among front‐line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1653–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng, M., Wei, L., Shi, X., Cao, G., Wei, Y., Xu, H., Zhang, X., Zhang, W., Xing, S., & Wei, H. (2020). Mental distress and influencing factors in nurses caring for patients with COVID‐19. Nursing in Critical Care, 26(2), 94–101. 10.1111/nicc.12528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., Mao, M., Wang, S., Yin, R., Yan, H. O., Jin, Y., & Cheng, Y. (2021). Posttraumatic growth in Chinese nurses and general public during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 1–11. 10.1080/13548506.2021.1897148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Master, A. N., Su, X., Zhang, S., Guan, W., & Li, J. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID‐19 outbreak on frontline nurses: A cross‐sectional survey study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29, 4217–4226. 10.1111/jocn.15454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson, K., Shanafelt, T., & Southwick, S. (2020). Pandemic‐driven posttraumatic growth for organizations and indivdiuals. (Viewpoint). Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 324(18), 1829–1830. 10.1001/jama.2020.20275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins, A., Bovin, M. J., Kimerling, R., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., Pless Kaiser, A., & Schnurr, P. P. (2015). Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM‐5 (PC‐PTSD‐5) [Measurement instrument]. https://www.ptsd.va.gov [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ross, C. A., Berry, N. S., Smye, V., & Goldner, E. M. (2018). A critical review of knowledge on nurses with problematic substance use: The need to move from individual blame to awareness of structural factors. Nursing Inquiry, 25(2), e12215. 10.1111/nin.12215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C. A., Jakubec, S. L., Berry, N. S., & Smye, V. (2018). “A two glass of wine shift”: Dominant discourses and the social organization of nurses’ substance use. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 5, 1–12. 10.1177/2333393618810655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C. A., Jakubec, S. L., Berry, N. S., & Smye, V. (2019). The business managing nurses’ substance‐use problems. Nursing Inquiry, 27, 1–12. 10.1111/nin.12324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahrour, G., & Dardas, L. A. (2020). Acute stress disorder, coping self‐efficacy and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID‐19. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1686–1695. 10.1111/jonm.13124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Q., Zhang, X., Wang, X., & Cai, C. (2020). The influence of experiences of involvement in the COVID‐19 rescue task on the professional identity among Chinese nurses: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management, 28, 1662–1669. 10.1111/jonm.13122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, R., Yu, T., Luo, K., Teng, F., Liu, Y., Luo, J., & Hu, D. (2020). Experiences of clinical first‐line nurses treating patients with COVID‐19: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management, 28, 1381–1390. 10.1111/jonm.13095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013). The Life Events Checklist for DSM‐5 (LEC‐5)—Standard. [Measurement instrument]. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/

- Yudko, E., Lozhkina, O., & Fouts, A. A. (2007). Comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32(2), 189–198. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.