Several faster‐spreading variants of concern (VOC) of the SARS‐CoV‐2 coronavirus have recently emerged in the United Kingdom (Alpha, B.1.1.7), South Africa (Beta, B.1.351), Brazil (Gamma, P.1) and India (Delta, B.1.617) and spread to more than 100 countries, including Bangladesh (O'Toole et al., 2020). Researchers are concerned about these new variants due to the possibility of switching pathogenicity or virulence and altering the activities of antibodies elicited by vaccines or natural infections (Esper et al., 2021). These VOC and several other variants under investigation (VUI), including Eta (B.1.525) variant that emerged in Nigeria, have already been identified in Bangladesh (GISAID.ORG). The recent emergence of VOC and VUI prompted us to monitor SARS‐CoV‐2 variants in Dhaka city.

Between 1 January and 10 June 2021, a total of 24,085 nasopharyngeal swab specimens were collected from COVID‐19 suspected patients attending 24 collection booths in Dhaka city. The specimens were tested for the SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA using real‐time PCR daily‐basis in the Virology Laboratory at icddr,b, and 5331 (22.1%) were positive. The positive samples with Ct values ≤ 25 (n = 621) were screened for variants by sequencing the spike gene using the Sanger method (Hossain et al., 2021). A subset of variants was confirmed by complete genome sequencing using MinION nanopore assay (Quick, 2020).

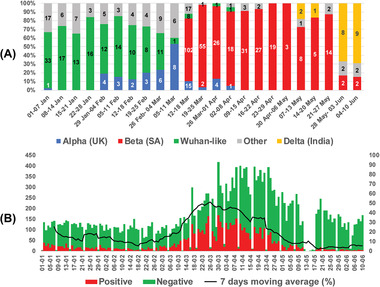

The Alpha variant was first identified on 6 January 2021 (Hossain et al., 2021), which gradually increased over time with the highest positivity rate (53%) in the second week of March 2021 by replacing Wahan‐like and other pre‐existing variants (Figure 1a). A dramatic change in the distribution of variants was observed after the Beta variant was detected on 16 March 2021. It became the most prevalent variant by replacing almost all other variants, coinciding with the increased positivity rate of SARS‐CoV‐2 in Dhaka city (Figure 1b) and resulting in the second wave of COVID‐19, causing a huge public health concern (DGHS, 2021; Dong et al., 2020). Most remarkably, the Beta variant constituted 90% of the variants circulating in Dhaka city during April–May 2021. The Delta variant appeared at the beginning of May and has become the most dominant variant at the end of May and the beginning of June 2021 (68%) (Figure 1a).

FIGURE 1.

(a) Weekly distribution of circulating SARS‐CoV‐2 variants in Dhaka city. (b) Daily distribution of specimens tested for SARS‐CoV‐2. The primary axis denotes the number of samples (green‐negative and red‐positive), and the secondary axis denotes the percentage of positive samples (line graph indicates 7 days moving average for positivity rate)

To date, more than 1700 SARS‐CoV‐2 genomes from Bangladesh have been uploaded to the public database, GISAID.ORG, which is less than 0.2% of the total number of COVID‐19 positive cases identified in the country. The current genomic sequencing effort occasionally conducted by different research institutes and universities is not enough to produce a comprehensive snapshot. The huge fluctuation in variant distribution observed through our study warrants continuous monitoring of the SARS‐CoV‐2 throughout the country, which is a crucial tool that will help drive public‐health decisions quickly by the national pandemic‐prevention programmes.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MR, SEA and TA conceived the study. TS, MEH, MHK and MZR have supervised all laboratory and field activity, including sample collection, testing and data curations. SR, MMR and MEH carried out the laboratory work and analysis of data. SR drafted the first manuscript, and all authors discussed the results, critically read and revised the manuscript and gave the final approval for publication.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The activity of this study and the manuscript was approved by the icddr,b institutional review board.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The SARS‐CoV‐2 variant monitoring is a part of ‘COVID‐19 testing and tracing in Bangladesh’ study funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Investment ID INV‐017556). icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to its research efforts. icddr,b is also grateful to the Government of Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden and the UK for providing core/unrestricted support.

Rahman, M. , Shirin, T. , Rahman, S. , Rahman, M. M. , Hossain, M. E. , Khan, M. H. , Rahman, M. Z. , El Arifeen, S. , & Ahmed, T . (2021). The emergence of SARS‐CoV‐2 variants in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 68, 3000–3001. 10.1111/tbed.14203

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data and materials used in this work were publicly available. Sequences were published in GISAID (www.gisaid.org) database under the accession numbers EPI_ISL_1715160, EPI_ISL_1715161, EPI_ISL_1715163, EPI_ISL_1715164, EPI_ISL_1715165, EPI_ISL_1715166, EPI_ISL_1715168, EPI_ISL_1715169, EPI_ISL_1715170, EPI_ISL_1717025, EPI_ISL_1793786, EPI_ISL_1793787, EPI_ISL_1793789, EPI_ISL_1793791, EPI_ISL_1828781, EPI_ISL_890237, EPI_ISL_2233364, EPI_ISL_2233365, EPI_ISL_2233366, EPI_ISL_2233369, EPI_ISL_2233372, EPI_ISL_2233373, EPI_ISL_2233377, EPI_ISL_2233379, EPI_ISL_2235496, EPI_ISL_2233380, EPI_ISL_2233381, EPI_ISL_2361892, EPI_ISL_2361893, EPI_ISL_2361895, EPI_ISL_2361896, EPI_ISL_2361897, EPI_ISL_2361903 and one sequence in GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) under accession number MW785207.

REFERENCES

- DGHS . (2021). Coronavirus (COVID‐19) update https://dghs.gov.bd/index.php/en/home/5343‐covid‐19‐update

- Dong, E. , Du, H. , & Gardner, L. (2020). An interactive web‐based dashboard to track COVID‐19 in real time. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(5), 533–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper, F. P. , Cheng, Y.‐W. , Adhikari, T. M. , Tu, Z. J. , Li, D. , Li, E. A. , Farkas, D. H. , Procop, G. W. , Ko, J. S. , & Chan, T. A. (2021). Genomic epidemiology of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection during the initial pandemic wave and association with disease severity. JAMA Network Open, 4(4), e217746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. E. , Rahman, M. M. , Alam, M. S. , Karim, Y. , Hoque, A. F. , Rahman, S. , Rahman, M. Z. , & Rahman, M. (2021). Genome sequence of a SARS‐CoV‐2 strain from Bangladesh that is nearly identical to United Kingdom SARS‐CoV‐2 variant B. 1.1. 7. Microbiology Resource Announcements, 10(8). 10.1128/MRA.00100-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole, A. , Scher, E. , Underwood, A. , Jackson, B. , Hill, V. , McCrone, J. , Ruis, C. , Abu‐Dahab, K. , Taylor, B. , & Yeats, C. (2020). Pangolin: Lineage assignment in an emerging pandemic as an epidemiological tool . https://cov‐lineages.org/global_report_B.1.1.7.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Quick, J. (2020). nCoV‐2019 sequencing protocol v2 (GunIt) V. 2 . 10.17504/protocols.io.bdp7i5rn [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials used in this work were publicly available. Sequences were published in GISAID (www.gisaid.org) database under the accession numbers EPI_ISL_1715160, EPI_ISL_1715161, EPI_ISL_1715163, EPI_ISL_1715164, EPI_ISL_1715165, EPI_ISL_1715166, EPI_ISL_1715168, EPI_ISL_1715169, EPI_ISL_1715170, EPI_ISL_1717025, EPI_ISL_1793786, EPI_ISL_1793787, EPI_ISL_1793789, EPI_ISL_1793791, EPI_ISL_1828781, EPI_ISL_890237, EPI_ISL_2233364, EPI_ISL_2233365, EPI_ISL_2233366, EPI_ISL_2233369, EPI_ISL_2233372, EPI_ISL_2233373, EPI_ISL_2233377, EPI_ISL_2233379, EPI_ISL_2235496, EPI_ISL_2233380, EPI_ISL_2233381, EPI_ISL_2361892, EPI_ISL_2361893, EPI_ISL_2361895, EPI_ISL_2361896, EPI_ISL_2361897, EPI_ISL_2361903 and one sequence in GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) under accession number MW785207.