Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Dear Editor,

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a rare and severe autoimmune disorder of skin and mucosa. In PV, the production of autoantibodies against desmosomal proteins of the skin, namely desmoglein (Dsg) 1 and Dsg3, leads to a clinical phenotype characterized by blistering and severe erosions. Several factors including genetic susceptibility, certain drugs and malignant disorders have been reported to trigger or exacerbate PV.1 Here, we report the first case of a patient, who developed PV following COVID‐19 vaccination with the mRNA vaccine BNT162b2 (Comirnaty®, Biontech/Pfizer).

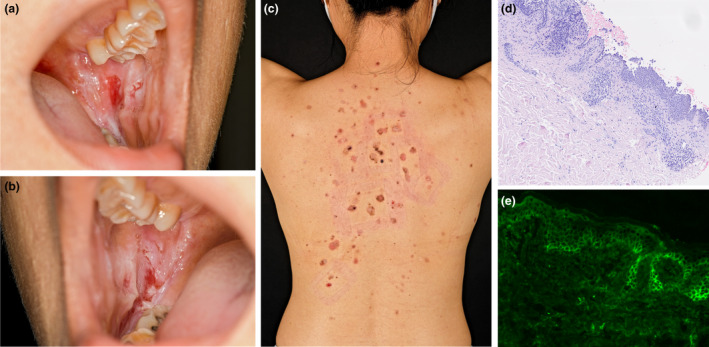

A 40‐year‐old female patient of Asian ethnicity was referred to our department following the outbreak of painful, non‐healing erosions of the oral mucosa, the trunk and the back (Fig. 1a–c). The patient’s history revealed that first oral lesions occurred mid‐January 5 days after the first administration of BNT162b2. Three days after the patient received the second vaccine dose, oral lesions worsened heavily; in addition, blisters and erosions occurred on the upper part of the body. Prior to vaccination, the patient was otherwise healthy, without any history of skin disease and without any medication. Due to the clinical presentation suspicious for pemphigus disease, we performed skin and blood sampling. The histology of lesional skin showed acantholysis within the lower epidermal layers, and the presence of a dense lymphocytic dermal infiltrate, accompanied by a rich presence of plasma cells (Fig. 1d). Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin revealed a prominent deposition of IgG in a honeycomb‐like intercellular epidermal pattern (Fig. 1e). Finally, we detected high titres of autoantibodies against Dsg3 and Dsg1 in the patient’s sera (974 and 124 RE/mL, respectively) (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). With these findings, we confirmed the clinically suspected diagnosis of PV and initiated an immunosuppressive treatment with oral prednisone (1mg per kg body weight, eventually tapered) and azathioprine (100mg/day).2 This approach ceased blistering and diminished autoantibody production. The patient is currently under regular clinical follow‐ups in our clinic.

Figure 1.

Clinical appearance and immunohistology of pemphigus in a patient vaccinated against SARS‐CoV‐2. (a and b) Extensive painful erosions of the oral mucosa; (c) erosive annular red‐brownish lesions on the upper back; (d) histology of lesional skin, with pronounced acanthosis and strong dermal infiltration; (e) direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin presenting intercellular epidermal IgG deposition in a honeycomb‐like pattern.

Single cases of manifestation of PV following vaccination have been reported after administration of vaccines against rabies, influenza, hepatitis B, diphtheria, typhoid, tetanus and anthrax (Table 1). The BNT162b2 vaccine is a lipid nanoparticle‐formulated nucleoside‐modified RNA (modRNA) encoding the SARS‐CoV‐2 full‐length spike protein in its perfusion conformation. Following injection, common side effects like local redness, swelling, pain or systemic effects like fever, headaches, joint pain or diarrhoea are commonly described.3 The clinical appearance of autoimmune disorders after antiviral vaccinations is rare.4 Different processes such as molecular mimicry, inflammatory dysregulation in genetically susceptible persons, epitope spreading or bystander activation seem to be involved in the onset of autoimmunity following vaccinations.4 BNT162b2 injection provokes a potent T and B cell activation. After inoculation, there is a profound CD4+ and CD8+ expansion, with production of IFN‐ɣ, IL‐2 and skewing of T cells towards a Th1 profile.3 Similarly, vaccination boosts B cell activity, with a rapid increase in the numbers of plasma cells, memory B cells and level of antibodies.3 Single individuals develop a strong IL‐4 production following vaccination with BNT162b1.3 Although data regarding IL‐17 and IL‐21 production following BNT162b2 inoculation are still missing, the production of IL‐17 and IL‐21 seems to play an important role in vaccine‐induced immunological protection.5, 6 Of note, cytokines like IL‐4, IL‐17 and IL‐21 are linked to germinal centre activation and critically implicated in autoimmune disorders like pemphigus, especially in its initial phase.7 However, a strong antibody response following vaccination usually requires more than 5 days. In patients vaccinated with BNT162b1, specific antibodies appear 14–21 days later.3 It is very likely that in our patient the vaccination with BNT162b2 boosted her T/B cell response that resulted in the unwanted onset of pemphigus. Genetic susceptibility may promote such a side effect.

Table 1.

Reported cases of pemphigus triggered or exacerbated following vaccination

| Vaccine against | Type | Disease type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rabies | Human diploid cell vaccine | PV—new onset | Yalçin B, J Dermatol, 2007 |

| Influenza |

N/a N/a |

PV—exacerbation PV—new onset |

De Simone C, Clin Exp Dermatol, 2008 Mignogna M, Int J Dermatol, 2000 |

| Hepatitis B | Recombinant (Engerix‐B) | PV—new onset | Berkun Y, Autoimmunity, 2005 |

| Typhoid | Typhim Vi | PV—new onset | Bellaney G, Clin Exp Dermatol, 1996 |

| Tetanus | N/a | PF—exacerbation | Korang K, Acta Derm Venereol, 2002 |

| Anthrax | Anthrax vaccine absorbed (AVA) | PV—new onset | Muellenhoff M, J Am Acad Dermatol, 2004 |

| Sars‐CoV2 | Modified mRNA | PV—new onset | Solimani F, J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2021 |

N/a, not available; PV, Pemphigus vulgaris; PF, Pemphigus foliaceus.

Even if we cannot identify a direct pathological link between the BNT162b2 and the onset of PV lesions, there is a clear temporal relation between these two events. This report does not intend to create public concern regarding the safety of this vaccine, yet occurrence of vaccine‐related events warrants documentation and may help to define risk profiles for patients in the future, especially in those with subclinical autoantibody titres.

Acknowledgements

The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to the publication of their case details. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) FOR 2497/TP02 (GH133/2‐2 to Kamran Ghoreschi).

References

- 1.Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi Het al. Pemphigus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017; 3: 17026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amber KT, Maglie R, Solimani F, Eming R, Hertl M. Targeted therapies for autoimmune bullous diseases: current status. Drugs 2018; 78: 1527–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahin U, Muik A, Derhovanessian Eet al. COVID‐19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T cell responses. Nature 2020; 586: 594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal Y, Shoenfeld Y. Vaccine‐induced autoimmunity: the role of molecular mimicry and immune crossreaction. Cell Mol Immunol 2018; 15: 586–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Priebe GP, Walsh RL, Cederroth TAet al. IL‐17 is a critical component of vaccine‐induced protection against lung infection by lipopolysaccharide‐heterologous strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Immunol 2008; 181: 4965–4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spensieri F, Borgogni E, Zedda Let al. Human circulating influenza‐CD4+ ICOS1+IL‐21+ T cells expand after vaccination, exert helper function, and predict antibody responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 14330–14335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holstein J, Solimani F, Baum Cet al. Immunophenotyping in pemphigus reveals a TH17/TFH17 cell–dominated immune response promoting desmoglein1/3‐specific autoantibody production. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 147: 2358–2369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]