Abstract

Background:

Women with a refugee background and their families who have settled in a new country can be expected to have low health literacy, and this may be a contributing factor to poor perinatal outcomes.

Brief description of activity:

Effective communication is critical for meaningful engagement with patients. Teach-Back is an interactive tool that can assist health professionals confirm whether they are communicating effectively so they are understood and their patients can apply health information. However, evidence for its effectiveness in interpreter-mediated appointments is lacking.

Implementation:

An antenatal clinic caring for women with a refugee background provided an opportunity to explore the benefits and challenges of using Teach-Back with this population. Staff had access to informal on-site training on health literacy and Teach-Back, tried using Teach-Back in their clinical work, and were then asked to provide feedback on what it was like using Teach-Back.

Results:

This case study identified several challenges when applying Teach-Back in interpreter-mediated antenatal health care appointments associated with differing cultural nuances and cultural practices.

Lessons learned:

Building interpersonal and cross-cultural communication capabilities among health professionals is essential in advancing health literacy workforce practice to improve the health literacy of non-English speaking refugee communities. Although Teach-Back may have the potential to be a powerful tool in promoting the health literacy of these women during pregnancy, further research is required to ensure that its use promotes safe and equitable health care. [HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice. 2021;5(3):e256–e261.]

Plain Language Summary:

This article reports a case study of using Teach-Back in pregnancy appointments involving a midwife and an interpreter. Several challenges for using Teach-Back were identified due to differences in cross-cultural communication. Supporting clinicians and interpreters to work together to implement Teach-Back is required to improve cross-cultural communication and women's health literacy.

There is compelling evidence that women with a refugee background have higher rates of stillbirth, fetal death in-utero, and perinatal mortality (Heslehurst et al., 2018). Some women from this population are also less likely to attend the recommended number of antenatal check-ups and report poor experiences of maternity care (Yelland, Riggs, Small, et al., 2015). Refugee populations are also known to have higher risks of a range of physical, psychological, and social health problems related to trauma experiences, stress associated with resettlement, and persistent disadvantage in the developed countries in which they live.

Background

Low health literacy can be expected in women of refugee background as they learn to navigate a new country, language, and culture (Riggs et al., 2016). Low health literacy is inextricably linked to poor engagement with health information, health services, and poor health outcomes (Greenhalgh, 2015). Health-literate health services make it easier for people to navigate, understand, and use information and services to take care of their health (Brach et al., 2012). For people with refugee backgrounds, engagement with health information, health services, and preventive health activities is challenging (Riggs et al., 2020).

Although health literacy is commonly defined as an individual trait (the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services that are needed to make appropriate health decisions) (Berkman et al., 2010), it is acknowledged that health system reform is required to better align health care delivery with people's skills and abilities (Rudd & Anderson, 2006). Strengthening organizations' ability to promote health literacy requires testing innovative strategies and determining their impact and effectiveness.

Prior Research on Teach-Back

Teach-Back is a potentially useful communication and engagement strategy for clinicians to incorporate into consultations. Teach-Back evolved from clinical encounters with English-speaking patients, in which physicians were observed checking patient recall of information about the management of their diabetes (Schillinger et al., 2003). It is an interactive, evidence-based communication strategy that requires health professionals to ask people to repeat what has been explained to them but in their own words (DeWalt et al., 2010; Koh & Rudd, 2015). If a patient understands what the physician has told them, then they are able to teach back the information accurately. Teach-Back can be used to explore understanding and how people will use health information. The onus is on the health care professional to make sure their explanation has been clear, understood, likely to be remembered and applied, and to make it known that it is not a test of the person's capacity to recall the information verbatim. Paasche-Orlow and Wolf (2010) suggest that inability to recall health information should not be framed as a patient deficit but instead as a challenge to health care providers to reach out and communicate more effectively. Teach-Back can potentially play an important role in delivery of equitable access to health care and health information (Volandes & Paasche-Orlow, 2007).

However, there is little evidence of how this communication tool is used when clinicians work with interpreters to provide health information to clients with low-English proficiency (Morony et al., 2017). Typically, interpreters provide a language service with strict parameters governing their role. This includes only interpreting what is said between the clinician and patient, with no interjecting. There is also no ongoing relationship with the client, with the only exception being subsequent episodes of care where the same interpreter may be requested to support continuity. Credentialed interpreters operate under a code of professional ethics to ensure their services are impartial and confidential and should not influence the discussion in any way (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2014b). Interpreters are often arranged via external agencies employing a pool of interpreters who are assigned to “job requests.” This means interpreters frequently work across multiple organizations with little continuity. Some hospitals employ interpreters in major languages directly, and use “external” interpreters only for “out of hours” consultations and for less common languages. Some interpreters who are employed by hospitals (rather than contracted by an interpreting agency) may have additional roles as part of their position, such as supporting patients to access and navigate health services.

Brief Description of Activity

The antenatal health care setting provides opportunities for an active and preventive learning environment for health professionals to engage with women (and their families) in a way that can promote health literacy. In Australia, public care is offered to women who are pregnant and their families through public hospital antenatal clinics or in shared-care arrangements between a community-based general practitioner and hospital antenatal clinic. Women in this public care system have labor, birth care, and postnatal care provided by hospital staff. Guidelines suggest that for a woman's first pregnancy (without complications), she should have a minimum of 10 scheduled appointments that include clinical check-ups and focus on the provision of information and advice (Department of Health, 2018). Given that the evidence holds promise for the effectiveness of Teach-Back as a tool for improving engagement in health care and health literacy, we were keen to trial its use in an antenatal setting. In particular, we aimed to explore the usefulness, benefits, and challenges of using Teach-Back with women of low-English proficiency of refugee background during pregnancy. Our research question was “what is the experience of using teach-back in antenatal care from the perspective of a midwife and interpreter?”

This article presents learnings from Bridging the Gap, which is an innovative partnership of 12 agencies that came together over 3.5 years to address inequalities in refugee perinatal health through quality and safety health systems reform (Yelland, Riggs, Szwarc, et al., 2015). A quality improvement activity was co-designed by a working group from the partnership to trial the application of Teach-Back. This article reports the lessons learned from incorporating Teach-Back in antenatal care consultations involving interpreters with women from refugee backgrounds and provides considerations for organizations to support health care workers to use Teach-Back.

Human research ethics approval was obtained by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Royal Children's Hospital (approval 33179).

Implementation

Applying Teach-Back in the Antenatal Setting

Initial conversations with midwifery staff about the potential to use Teach-Back with women from refugee backgrounds indicated a lack of formal familiarity with Teach-Back as an approach to effective communication. However, after explaining what Teach-Back involved, the response that followed was typically: “‘Oh yes, we always do that.”

It was believed that this way of communicating was nothing new, and that midwives considered this type of communication was standard practice with all patients. When the researcher (ER) inquired about how Teach-Back was used in consultations with interpreters, midwives reported that the method was rarely used with patients, at least not in a procedural way as described in the literature (DeWalt et al., 2010). One of the identified barriers was the focus on imparting information as efficiently as possible given there was no additional time allocated for appointments mediated through an interpreter. For example, a common reflection from midwives working in antenatal clinics is:

We have so many women to see today, they have complex problems that we have to deal with, and we have limited time with them.

At a hospital involved in the Bridging the Gap program (Yelland, Riggs, Szwarc, et al., 2015), staff including midwives and interpreters were provided with on-site informal training on using Teach-Back. An antenatal clinic in the community had a hospital-employed, on-site interpreter booked for several back-to-back appointments with Karen refugee-background women from Burma. (The Karen people are an ethnolinguistic group of people who reside mostly in southern and southeastern Burma.) In addition, credentialed interpreters employed by this hospital have an additional role that includes undertaking health promotion activities to assist consumers in accessing services and to participate in other relevant activities.

A midwife and a hospital-employed on-site interpreter working in a “continuity of care” model of care and their management agreed to try using Teach-Back and provide reflective feedback on the process. The researcher met with both the midwife and interpreter after the clinic session was finished to reflect on their experiences of using Teach-Back with clinic clients. The researcher documented the conversations.

Results

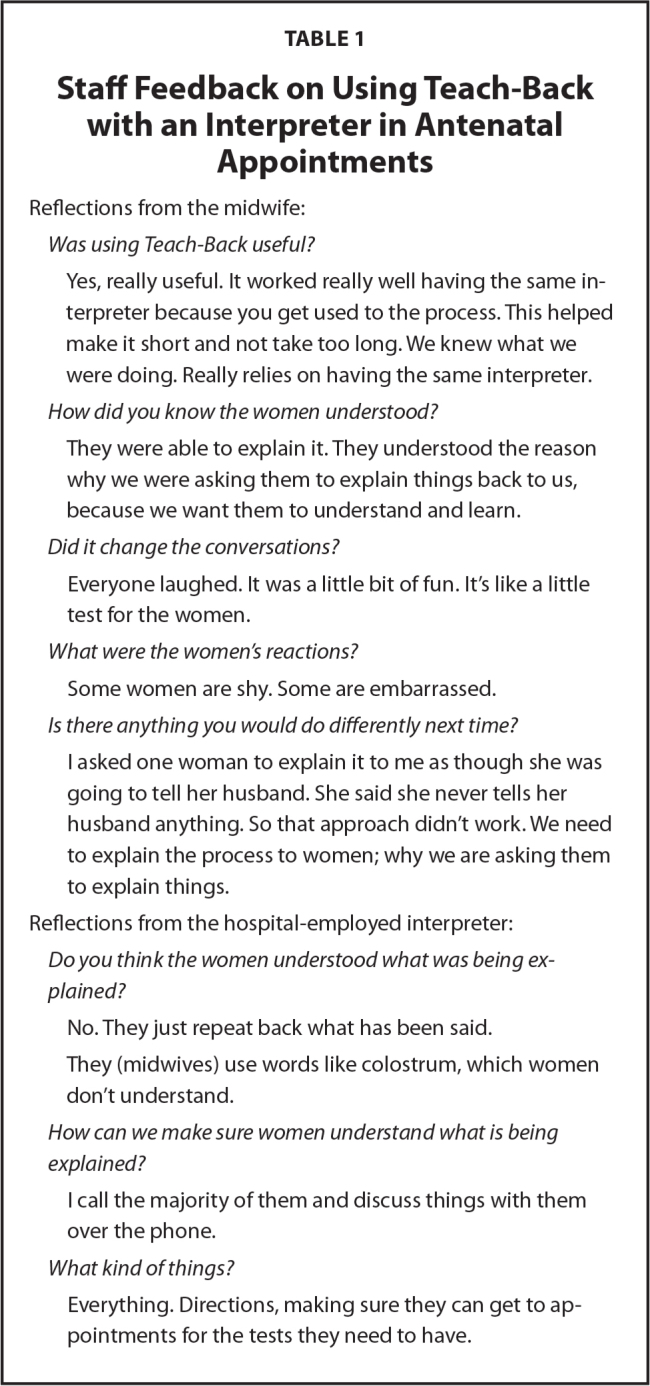

Table 1 presents the conversations between the researcher, midwife, and interpreter reporting their experiences of using Teach-Back with clients.

Table 1.

Staff Feedback on Using Teach-Back with an Interpreter in Antenatal Appointments

| Reflections from the midwife: |

| Was using Teach-Back useful? |

| Yes, really useful. It worked really well having the same interpreter because you get used to the process. This helped make it short and not take too long. We knew what we were doing. Really relies on having the same interpreter. |

| How did you know the women understood? |

| They were able to explain it. They understood the reason why we were asking them to explain things back to us, because we want them to understand and learn. |

| Did it change the conversations? |

| Everyone laughed. It was a little bit of fun. It's like a little test for the women. |

| What were the women's reactions? |

| Some women are shy. Some are embarrassed. |

| Is there anything you would do differently next time? |

| I asked one woman to explain it to me as though she was going to tell her husband. She said she never tells her husband anything. So that approach didn't work. We need to explain the process to women; why we are asking them to explain things. |

| Reflections from the hospital-employed interpreter: |

| Do you think the women understood what was being explained? |

| No. They just repeat back what has been said. |

| They (midwives) use words like colostrum, which women don't understand. |

| How can we make sure women understand what is being explained? |

| I call the majority of them and discuss things with them over the phone. |

| What kind of things? |

| Everything. Directions, making sure they can get to appointments for the tests they need to have. |

Without being an observer in the consultations or using video recordings of the consultation, these conversations are useful feedback for unpacking the application of Teach-Back in a busy antenatal setting. What is illuminating in these conversations is the midwife's perception of what is being explained and how she perceives women's understanding. The midwife's prioritization of medical information despite women's lack of understanding of words (e.g., colostrum) indicates that it is difficult to determine women's actual understanding of what is being conveyed.

Reflecting on the midwife's comment that everyone laughed, discussions with the interpreter explained that in Karen culture smiling and/or laughing can be a sign of “shame, fear, embarrassment, nervousness, shyness, or trying to hide their real emotion.” The midwife may have interpreted the laughing as a sign of fun, enjoyment, or amusement, so there is the potential for this reaction to Teach-Back to be misunderstood in a cross-cultural context.

In discussions with the interpreter, she shared that Karen people may try to avoid “being a burden” to health professionals by not asking questions, as they feel they are wasting the time of the clinician. To overcome this, making sure that the appointment does not feel rushed and presenting the consultation as the women's time to make sure she feels that she has understood what is happening for her and her baby during pregnancy is important. Encouraging women to ask questions is good practice for helping mothers and families to become familiar with pregnancy care and other support services for families in Australia. For person-centered care to be realized, women need to be able to share their concerns, priorities, and what they would like to know during their appointments. We recognize this is challenging in the context of busy antenatal clinics, which can translate into perceptions of urgency and a need for clinicians to convey as much information as possible while the interpreter is present.

Interpreters have strict guidelines in their role as a language conduit between clients and providers. They are meant to be un-noticeable in the consultation in the flow of two-way communication between the clinician and the client. Yet, in this case study, the hospital-employed interpreter was aware of what the midwife was attempting to do by using Teach-Back and could see that women did not understand the information conveyed. Antenatal appointments are typically booked back-to-back with limited time available for the midwife and interpreter to discuss women's needs before and after each client. Allowing time for briefing interpreters has been documented as good clinical practice (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2014a). An option for interpreters to brief clinicians about cultural considerations in the context of health care warrants attention. The potential for interpreters to have an additional role as a cultural broker has been previously reported (Gartley & Due, 2017), whereby cultural insights can be shared with clinicians to support a welcoming and accepting approach to the encounter.

The insight demonstrated by the midwife that we need to explain why we are asking women to explain things reveals that there was likely to be some hesitation or reluctance by women to participate in Teach-Back. Just as best practice guidelines for working with interpreters outline the need to explain the role of the interpreter, the use of Teach-Back needs to be explained to women in a supportive and nonthreatening way. It is important to ensure the patient does not feel as though she is being tested. To lessen the likelihood of this occurring, the midwife and interpreter need to work together to develop an approach tailored to each client. Ideally, this would be discussed prior to commencing the consultation. Furthermore, all staff (including interpreters) would likely benefit from participating in professional development in the use of Teach-Back. Future research could include exploring an appropriate model for using Teach-Back with interpreters who operate in typical health care roles, and how best to explain to patients why they are being asked to restate what the clinician has said.

Lessons Learned

Cross-Cultural Team-Based Approaches to Health Care

Midwives fulfill an important clinical role in antenatal care that encompasses completing numerous clinical tasks, professional duties, and adherence to hospital protocols. The clinician/interpreter relationship can be considered a team, especially for block-booked appointments in which they are working together for a substantial and re-occurring period of time.

For a team to be cohesive, there are aspects that require attention to support the functioning of the team. Some of these tasks could be described as encouraging participation from all team members, dealing with conflict and tension, and listening to each other. However, when a team member, such as the interpreter in this instance, starts from a standpoint of different cultural values that include privacy, discretion, nonconfrontation, and dealing with issues on a one-on-one basis, these functions of good practice for teamwork are likely to be unfamiliar. In this case study, the midwife is responsible for what occurs in the clinical encounter, but the hospital-employed interpreter in their expanded role supports what happens around the encounter.

The interpreter explained that the Karen culture is particularly polite and respectful, especially to people in positions of authority or knowledgeable positions, such as health professionals. This may be expressed as acquiescence, agreeableness, passivity, and fearful behavior. Within teams, all team members need to feel safe to be able to speak up and disagree or put a different view forward. This also applies for women—they also need to feel safe to speak up, ask questions, and clarify information they do not understand.

Is Teach-Back Effective in Providing Cross-Cultural Health Care?

Building workforce and organizational capacity to address low health literacy is likely to translate to people having a better understanding of health information so that they can make more informed decisions about their health. A workforce equipped with health literacy strategies that engage consumers (McCormack et al., 2017) would make a significant contribution to improved health care experiences and health outcomes for people of refugee background (Zanchetta et al., 2013).

The juxtaposition of “tasks to be completed quickly” and “nonconfrontational respectful behavior” is likely to be common for many health professionals working with interpreters, given that interpreters are often from the same cultural background as the clients for whom they provide interpreting support. Balancing the need for effective and productive teamwork across cultures and disciplines takes time and a commitment to allowing team members to get to know each other. The importance of recognizing assumptions in health care communication has been documented, yet when they are acknowledged they can demonstrate strengthened communication with clients and improved access, use, and engagement with health services (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2015).

A recent report argues that “safety is more than the absence of physical harm; it is also the pursuit of dignity and equity” (Frankel et al., 2017). For people with a refugee background, many of whom have experienced the devastating effects of torture and trauma, their pathway to recovery can be long and painful, yet interactions with the health system can support healing and recovery (Victorian Foundation for the Survivors of Torture, 1998). Pregnancy, and the interactions with health services during this time, provide an opportunity for health professionals to play a role in rebuilding people's sense of safety and belonging and restore their dignity. Providing continuity of midwife and interpreter during pregnancy and childbirth can provide stability and predictability, and by applying effective engagement and communication techniques, women's trust with the team is likely to develop. The concept of relationship-centered care is relevant and can be achieved by giving patients a voice, acknowledging their social realities, and collaborating with them as equals (Nundy & Oswald, 2014; Samerski, 2019). These are all necessary components on the pathway to promoting the heath literacy of this population.

Study Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this the first case study to explore the role of Teach-Back with interpreters in an antenatal setting; however, this case-study was confined to one site with feedback from only one midwife and one interpreter.

The role of the hospital-employed interpreter in this case study was unusual because she had an expanded role allowing her to support patients to navigate their health care; hence, our findings cannot be generalized to other sites and settings. Further research is required in a range of settings and using generalist interpreters that represent the more common role found in health care. In this small case study, there was no stipulation as to what information was the focus of the exchange using Teach-Back. We did not determine in advance whether the focus would be clinical or practical (e.g., getting to appointments). Furthermore, we did not obtain feedback from women involved in these appointments. This would play an essential role in the triangulation of data to inform health care practice and policy. Further research is needed to explore these issues in other settings and contexts and to obtain the views of a broader range of stakeholders, including women and their families.

Conclusion

Building interpersonal and cross-cultural communication capabilities among health professionals is essential in advancing health literacy workforce practice to support the progression of health literacy in non–English-speaking communities with a refugee background. Although Teach-Back has the potential to be a powerful tool in promoting the health literacy of women with a refugee background during pregnancy, further research is required to explore the caveats and nuances of its application and effectiveness. Given this, systemic changes to health care provision and the evaluation of them may include making interpreter-mediated appointments longer, the allocation of time before and after each appointment for interpreters and clinicians to confer, and expanding the role of interpreters to support sharing information about cultural beliefs and communicative styles. To address inequalities and poor health outcomes, organizations must commit to supporting staff to be transparent and accountable with each other when trying out new ways to engage and communicate with women and their families. Health services that can achieve this are heading in the right direction for achieving effective communication that is critical for safe, effective, and equitable health care.

References

- Berkman , N. D. , Davis , T. C. , & McCormack , L. ( 2010. ). Health literacy: What is it? Journal of Health Communication , 15 ( Suppl. 2 ), 9 – 19 . 10.1080/10810730.2010.499985 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach , C. , Keller , D. , Hernandez , L. , Baur , C. , Parker , P. , Dreyer , B. , & Schillinger , D . ( 2012. ). Ten attributes of health literate health care organizations . National Academy of Medicine; website: https://nam.edu/perspectives-2012-ten-attributes-of-health-literate-health-care-organizations/ [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health . ( 2014a. ). Booking and briefing an interpreter. Interpreter information sheet #3 . https://www.ceh.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/LS3_Booking-and-briefing-an-interpreter.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health . ( 2014b. ). Interpreters: An introduction. Interpreter information sheet #1 . https://www.ceh.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/LS1_Interpreters-an-introduction.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health . ( 2015. ). Assumptions in the communication encounter . https://www.ceh.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/HL2_Assumptions-in-the-communication-encounter.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . ( 2018. ). Clinical practice guidelines: Pregnancy care . http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/4BC0E3DE489BE54DCA258231007CDD05/$File/Pregnancy%20care%20guidelines%205Feb18.pdf [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt , D. , Callahan , L. , Hawk , V. , Broucksou , K. , Hink , A. , Rudd , R. , & Brach , C . ( 2010. ). Health literacy universal precautions toolkit . Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; : https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/healthliteracytoolkit.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel , A. , Haraden , C. , Federico , F. , & Lenoci-Edwards , J . ( 2017. ). A framework for safe, reliable, and effective care [White paper]. Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Safe & Reliable Healthcare; . https://medischevervolgopleidingen.nl/sites/default/files/paragraph_files/a_framework_for_safe_reliable_and_effective_care.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gartley , T. , & Due , C. ( 2017. ). The interpreter is not an invisible being: A thematic analysis of the impact of interpreters in mental health service provision with refugee clients . Australian Psychologist , 52 ( 1 ), 31 – 40 . 10.1111/ap.12181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh , T. ( 2015. ). Health literacy: Towards system level solutions . BMJ (Clinical Research Edition) , 350 , h1026 10.1136/bmj.h1026 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslehurst , N. , Brown , H. , Pemu , A. , Coleman , H. , & Rankin , J. ( 2018. ). Perinatal health outcomes and care among asylum seekers and refugees: A systematic review of systematic reviews . BMC Medicine , 16 ( 1 ), 89 10.1186/s12916-018-1064-0 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh , H. K. , & Rudd , R. E. ( 2015. ). The arc of health literacy . Journal of the American Medical Association , 314 ( 12 ), 1225 – 1226 . 10.1001/jama.2015.9978 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack , L. , Thomas , V. , Lewis , M. A. , & Rudd , R. ( 2017. ). Improving low health literacy and patient engagement: A social ecological approach . Patient Education and Counseling , 100 ( 1 ), 8 – 13 . 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.007 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morony , S. , Weir , K. , Duncan , G. , Biggs , J. , Nutbeam , D. , & McCaffery , K. ( 2017. ). Experiences of teach-back in a telephone health service . HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice , 1 ( 4 ), e173 – e181 . 10.3928/24748307-20170724-01 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nundy , S. , & Oswald , J. ( 2014. ). Relationship-centered care: a new paradigm for population health management . Healthcare (Amsterdam, Netherlands) , 2 ( 4 ), 216 – 219 . 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.09.003 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paasche-Orlow , M. K. , & Wolf , M. S. ( 2010. ). Promoting health literacy research to reduce health disparities . Journal of Health Communication , 15 ( Suppl. 2 ), 34 – 41 . 10.1080/10810730.2010.499994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs , E. , Yelland , J. , Duell-Piening , P. , & Brown , S. J. ( 2016. ). Improving health literacy in refugee populations . The Medical Journal of Australia , 204 ( 1 ), 9 – 10 . 10.5694/mja15.01112 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs , E. , Yelland , J. , Szwarc , J. , Duell-Piening , P. , Wahidi , S. , Fouladi , F. , Casey , S , Chesters D. & Brown , S. ( 2020. ). Afghan families and health professionals' access to health information during and after pregnancy . Women and Birth; Journal of the Australian College of Midwives , 33 ( 3 ), e209 – e215 . 10.1016/j.wombi.2019.04.008 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd , R. E. , & Anderson , J. E. ( 2006. ). The health literacy environment of hospitals and health centers. Partners for action: Making your healthcare facility literacy-friendly . Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; . https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/135/2019/05/april-30-FINAL_The-Health-Literacy-Environment2_Locked.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Samerski , S. ( 2019. ). Health literacy as a social practice: Social and empirical dimensions of knowledge on health and healthcare . Social Science & Medicine , 226 , 1 – 8 . 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.024 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger , D. , Piette , J. , Grumbach , K. , Wang , F. , Wilson , C. , Daher , C. , Leong-Grotz , K. , Castro , C. , & Bindman , A. B. ( 2003. ). Closing the loop: Physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy . Archives of Internal Medicine , 163 ( 1 ), 83 – 90 . 10.1001/archinte.163.1.83 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Foundation for the Survivors of Torture . ( 1998. ). Rebuilding shattered lives . Foundation House; . https://foundationhouse.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Rebuilding%20Shattered%20Lives%20%E2%80%93%202nd%20Edition.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Volandes , A. E. , & Paasche-Orlow , M. K. ( 2007. ). Health literacy, health inequality and a just healthcare system . The American Journal of Bioethics , 7 ( 11 ), 5 – 10 . 10.1080/15265160701638520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelland , J. , Riggs , E. , Small , R. , & Brown , S. ( 2015. ). Maternity services are not meeting the needs of immigrant women of non-English speaking background: Results of two consecutive Australian population-based studies . Midwifery , 31 ( 7 ), 664 – 670 . 10.1016/j.midw.2015.03.001 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelland , J. , Riggs , E. , Szwarc , J. , Casey , S. , Dawson , W. , Vanpraag , D. , East , C. , Wallace , E. , Teale , G. , Harrison , B. , Petschel , P. , Furler , J. , Goldfeld , S. , Mensah , F. , Biro , M. A. , Willey , S. , Cheng , I. H. , Small , R. , & Brown , S. ( 2015. ). Bridging the gap: Using an interrupted time series design to evaluate systems reform addressing refugee maternal and child health inequalities . Implementation Science : IS , 10 ( 1 ), 62 10.1186/s13012-015-0251-z PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanchetta , M. , Taher , Y. , Fredericks , S. , Waddell , J. , Fine , C. , & Sales , R. ( 2013. ). Undergraduate nursing students integrating health literacy in clinical settings . Nurse Education Today , 33 ( 9 ), 1026 – 1033 . 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.05.008 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]