Abstract

Introduction:

Long-term care is an effective intervention that help older people cope with significant declines in capacity. The growing demand for long-term care signals a new social risk and has been given a higher political priority in China. In 2016, 15 local authorities have been selected to pilot the long-term care insurance programme. However, the current implementation of these programmes is fragmented, with a measure of uncertainty. This study aims to investigate the principles and characteristics of long-term care insurance policies across all pilot authorities. It seeks to examine the design of local long-term care insurance systems and their current status.

Methodology:

Based on the 2016 guidance, a systematic search for local policy documents on long-term care insurance across the 15 authorities was undertaken, followed by critical analysis to extract policy value and distinctive features in the delivery of long-term care.

Results:

The results found that there were many inconsistencies in long-term care policies across local areas, leading to substantial variations in services to the beneficiaries, funding sources, benefit package, supply options and partnership working. Policy fragmentation has brought the postcode lottery and continued inequity for long-term care.

Discussion:

Moving forward, local authorities need to have a clear vision of inter-organisational collaboration from the macro to the micro levels in directional and functional dimensions. At the national level, vertical governance should be interacted to outline good practice guidelines and build right service infrastructure. At the local level, horizontal organizations can collaborate to achieve an effective and efficient delivery of long-term care.

Keywords: older people, disability, long-term care, policy fragmentation, policy integration

Introduction

Aging population and associated disabilities have posed significant challenges to the sustainability of the healthcare system in China. According to the official statistics [1], there were about 33 million older people with partial or permanent disability in 2010, accounting for 19% of the total older population; among this, around 11 million (6%) were permanently disabled older population. The figures went up to over 40 million in 2015 and is projected by World Health Organization (WHO) to grow more quickly to reach 66 million in 2050 [2]. Disability trend in the elderly has placed serious impact upon the long-term care (LTC) system. LTC refers to a variety of healthcare services designed to assist people with disabling conditions in performing basic daily activities [3]. From the biological perspective, the aging process represents an accumulation of damages to cells and tissues over time [4]. This leads to a steady decline in physical and mental capacities as well as an enhanced vulnerability to infectious disease and chronic illness [5]. In 2013, there were nearly 50% of older people struggling with chronic diseases, and 37% of them experienced rapid deterioration in functional abilities [6]. According to projections, by 2030 older populations with one or more chronic illness can triple the number and nearly 80% of 60 years old and over will die from chronic diseases [2]. This dramatic increase requires a large amount of LTC, which indicates that the traditional family-oriented care system is unlikely to deliver them. Indeed, the increased needs for LTC have become a social risk [7]. Besides, influenced by traditional nursing home management systems, nursing institutions nowadays mainly provide daily care for older people with a severe shortage of other services such as recovery support, health maintenance, mental health and hospice care [8].

In response to these concerns, Chinese government introduced major reforms in the traditional aged service system by summarising experiences of German, Japan and South Korea’s practices on long-term care insurance (LTCI) [9]. In June 2016, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of P.R. China issued guidance on establishing long-term care insurance system in the pilot cities [10]. This guidance named 15 pilot cities to develop their LTCI system and to use social insurance as a source of financing LTC services. Commercial insurance was not adopted as it only benefits a few people— in other words, public governance and its policies are the key solution to the difficulty of facilitating high quality LTC [11,12]. Therefore, it is necessary to build a formal LTCI system after a period of implementing temporary care service polices [13]. As evidenced, the earlier LTCI is introduced, the better social effect is produced [14].

Despite the 2016 guidance, different pilot authorities adopted different policies and practices on LTCI. Therefore, there is a need to investigate the current status of the LTCI programmes across the country. This study is aimed at reviewing and assessing the performance and effectiveness of the LTCI policy regime in China. It will seek to address three research questions: (i) what policies each pilot authority has adopted to carry out LTCI; (ii) what are main features of and common issues with current LTCI policies; (iii) how to integrate these fragmented policies for improvement of the LTCI system at both national and local levels.

Integrating policies for LTCI: main rationales and theoretical framework

The LTCI system is defined as an insurance institution that offers daily life care, healthcare services and psychological help to disabled older people [15]. It normally consists of four dimensions: service beneficiaries, financing decisions, benefit package and service providers [16]. However, due to a lack of the united model, different programmes that supported specific ways of delivering LTC in different regions were implemented, causing policy fragmentation with their own characteristics in essential dimensions [17] as well as diverse influences on disabled people and their caregivers [7].

Firstly, service coverage and programme beneficiaries of LTC are restricted to certain members in each country. The LTCI system is designed to meet the escalating needs of older populations with chronic diseases or other disabilities [22,23]. However, because of differences in care needs between persons and in economic prosperity between and within countries, various LTCI policies were introduced to cover particular persons who meets the eligibility criteria [24,25]. By contrast, only a small number of older people have been insured within each country. For example, LTCI services covered just 5.8% of older population in South Korea, compared with 11% in OECD countries, 14.5% in Germany and 18.5% in Japan [26]. Service beneficiary is another key feature of the LTCI policy, which decides whether these vulnerable groups are qualified for LTC services and better life quality [27]. Unfortunately, due to bureaucratic obstruction and resource shortage, there were always some older people with critical conditions beyond coverage of the LTCI programme in many countries such as South Korea [28,29].

Secondly, funding sources and payment rates are found variably across the world. In principle, LTC services should be financed by multiple sources, with public funds making a dominant contribution [30]. However, the government in some countries often avoided financial responsibility or squeezed public spending in LTC services, such as prevention and treatment of Alzheimer disease in the US [31] and home-based healthcare in the UK [32]. More worryingly, following the increasing number of disabled older people and the expanding financial burden of health care, there have been substantial variation in funding availability and payment rates for LTC between low- and high-income regions [33,14]. For instance, there was a remarkable disparity in LTCI benefits between civic villages in Japan. When public resource is typically limited, government might focus attention to certain types of LTC services. For example, the UK government spent 21% to 58% of total social care funding on home care services [34].

Thirdly, inconsistencies generate through organising the LTCI system and providing medical care & senior services. Although person-centered care has been widely adopted by the LTCI system in most developed countries, many LTCI policies ignored the interdependent relation between public health and social care, resulting in the serious shortage of community rehabilitation and nursing care services [35]. Furthermore, re-assessment of people’s disability and fragmentation of public healthcare services often caused extra administrative cost [36]. Apparently, there needs to be a expanded, specialized and diversified supply system for the delivery of different LTC services. This, however, have not been generally accepted or respected by all interest groups. As a consequence, the fragmented supply system led to inefficiencies and poor effectiveness in LTC [37,38].

Fourthly, there is no unified standard on public-private partnership (PPP) and administrative capacity for the provision of LTC services. The LTCI systems across countries suffer from some same defects [39,40]: firstly, services for older people are provided by different departments or institutions; secondly, policies on healthcare services often conflict; thirdly, different approaches are taken to provide immediate treatment and LTC. In essence, the LTC system consists of a range of services and assistance, which require partnership working between different organizations including public- and private-sectors as well as effective coordination between skilled professionals, in order to meet the varying needs of all disabled people [41,42]. These essential requirements pose significant challenges to the management and operation of the LTC system. Specifically, how local government promotes PPP plays a significant role in achieving successful LTC services [43]. For example, the UK government developed a good relationship with private sectors under the slogan of big society small government for the delivery of LTC, with 81% of home-based care being provided by commercial sectors in 2011 rising from 5% in 1993 [44]. By contrast, both Holland [45] and Germany [46] did not establish a national market system for the supply of LTC services, leaving predominant responsibilities on public sectors.

Regional and local differences have exerted considerable impact on access to LTC services and benefits [47]. To address this, many countries have made some adjustments to the existing LTCI system. However, there is still the fragmentation of responsibilities and policies for LTC provision. Policy fragmentation means a policy system with logical disjunction between policy values, policy objectives, policy practices, which leads to negative effects on functional effectiveness of public policy and organizational coordination in policy implementation [18]. It is mainly caused by fragmented governance, in which a large number of subnational administrative units are created and they have their own administrative capacity and interest groups [19,20]. In brief, the extent of government fragmentation has critical implication for policy fragmentation [21].

Given the geographical and institutional fragmentation of LTC provision, the WHO introduced the integrated care for older people (ICOPE) approach to build a person-centred LTC system and improve intrinsic capacity in older people for healthy ageing [48]. Integrated care is defined as services, such as prevention, treatment and rehabilitation, being managed and delivered across various levels and sites within and beyond the health sector to meet diverse needs of people throughout their life span [49]. In this regard, achieving integrated care requires the involvement of multiple levels and sites, which can be divided into system (macro), service/organisational (meso) level and clinical (micro) level [50]. In the context of LTC provision, the ICOPE approach supports the integration of health services and social care by promoting inter-organisational collaboration in different forms at and beyond the macro, meso and micro level (e.g. relationships between partner organisations or between different professionals) [51]. It provides the potential for innovation of LTC delivery and sustainability of the healthcare system.

A number of countries have managed to implement ICOPE in care settings and to improve coordination between health and social entities [47]. Its effectiveness, however, remains inconsistent. In practice, LTC continues to be funded by multiple financing sources and provided by partner organisations at different levels from the macro to the micro [52]. Since the provision of LTC can be regulated at national, regional and local levels, there is a vertical split of responsibilities between different governance levels [53]. Also, responsibilities for LTC delivery are often shared horizontally by public organisations and private providers [47]. Therefore, implementation of integrated LTC for older people can be achieved in two operational dimensions, directionally and functionally [54]. The directional integration can be promoted vertically as well as horizontally, with the former coordinating partners along the chain of LTC provision (e.g. integrating primary with secondary care) and the latter coordinating organisations at the same level (e.g. integrating public health with social care) [55]. The functional integration gives attention to coordination of responsibilities between organisations, between professions, and between medicals. Valentijn et al. [56] further suggested to develop functional coordination across policymakers (system integration), administrators (organisational integration), professionals (professional integration), and practitioners (clinical integration). Additionally, from the perspective of administration, whether decisions can be made by authorities independently places heavy impact on the effectiveness of LTCI policy integration [57].

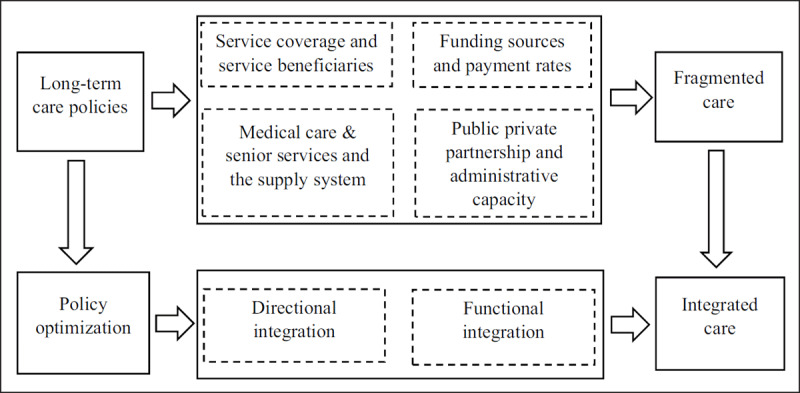

Based on fundamental principles and intrinsic elements of the ICOPE approach, a theoretical framework is evolved in this study to shift from fragmentation to integration of LTC systems. It will explore the fragmented features of current LTCI policies and initiatives and to develop a strategy for integration and optimization of LTC provision (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for policy integration on LTCI.

Materials and methods

Sampling

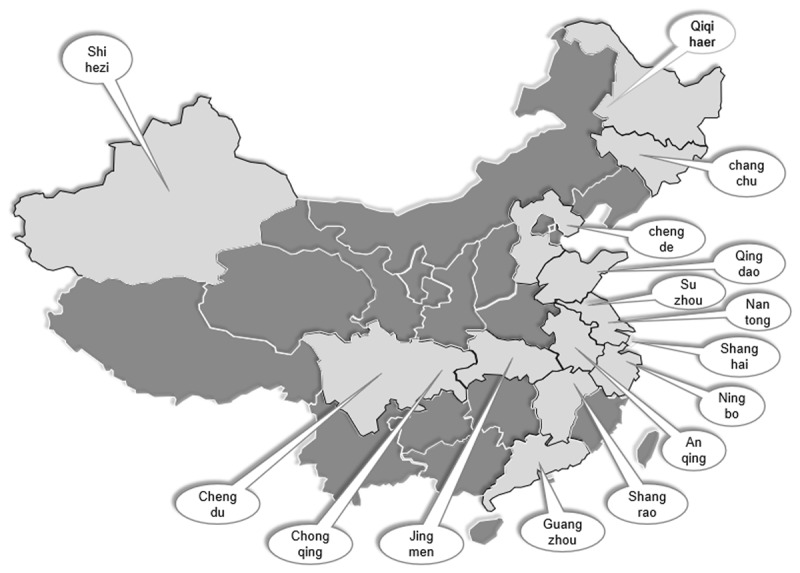

This study adopts a systematic review that supports evidence-based practice and is often applied in the field of healthcare [58]. Differentiated from the traditional literature review, the systematic review aims to identify all relevant evidence and provide comprehensive synthesis of the knowledge [59]. The 2016 guidance initially designates 15 cities to pilot the LTCI programme across China, including Chengde, Changchun, Qiqihar, Shanghai, Nantong, Suzhou, Ningbo, Qingdao, Guangzhou, Anqing, Shangrao, Jingmen, Chongqing; Chengdu, Shihezi. Given the nature of the research aim, only these 15 cities can serve as primary data sources. Therefore, purposive sampling was used for systematic analysation as it provides an opportunity to focus on a particular group and identify their themes and concepts in greater depth [60]. Figure 2 shows the geographical positions of all pilot cities, among these, 7 are in Eastern China, 2 in Northeast China, 2 in Southwest China, 1 in North China, 1 in Central China, 1 in South China, 1 in Northwest China. In practice, cities of Qingdao, Shanghai, Changchun and Nantong have launched initiatives to explore LTCI between July 2012 and October 2015. On the whole, all these local authorities are experiencing an accelerate growth of older population with physical frailty and have provided a set of LTC services for the elderly.

Figure 2.

The geographical position of pilot cities in China.

Data collection

The 2016 guidance sets the objective to establish the LTCI system for an aging population as well as to achieve social development and social sustainability. It sets up the following basic requirements: first, LTCI provides financial assistance to people who is no longer able to carry out basic tasks of daily life; second, LTCI mainly covers workers who have participated in employee basic medical insurance; third, pilot authorities are encouraged to establish different sources of funding for LTC; four, LTCI participants are considered to contribute to around 30% of the total cost of the LTC services. In practice, each pilot authority designed their own strategic policies to implement the LTCI programme in accordance with local economic development and the government’s capacity. The characteristics and performance of these policies are of great importance in expanding the LTCI system to the entire country. Therefore, all specific policy documents published on pilot authorities’ websites for the provision of LTCI was systematically collected and analyzed. Table 1 showed features and priorities of local LTCI policies across the pilot cities.

Table 1.

Policies on the implementation of LTCI across 15 pilot authorities.

|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CITIES | POLICY DOCUMENTS | GIVE POWER TO | PROVIDE SERVICES |

|

| |||

| Chengde |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Changchun |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Qiqihaer |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Shanghai |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Nantong |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Suzhou |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Ningbo |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Anqing |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Shangrao |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Qingdao |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Jingmen |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Guangzhou |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Chongqing |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Chengdu |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Shihezi |

|

|

|

|

| |||

Data analysis

An exploratory data analysis approach was employed to look at local LTCI systems, including service coverage, service beneficiaries, funding sources, eligible criteria, types of medical nursing care, the supply systems, PPP, and administrative capacity. NVivo was adopted to analyse and compare policy documents across the pilot authorities, thematic analysis was used to identify and report patterns within these qualitative data.

Results

Following over three years of implementing the LTCI programmes, some pilot authorities such as Qingdao and Chengdu have made significant progress. However, fragmentation of LTC for the elderly still remains. Table 2 presents the features and characteristics of LTCI policies across the 15 pilot authorities. The coverage of LTCI services is found in many variations, ranging from small, medium to large. 53.3% of local authorities provided basic medical insurance just for urban employees (small), compared with 40% for urban employees and urban-rural residents (large) and 6.7% for urban employees and residents (medium). About who are eligible for LTC services, in 13 out of 15 local authorities, only a small group of people with several disabilities were qualified for LTCI. The remaining 2 authorities expanded the qualification to a large size of populations with several and moderate disabilities. Unfortunately, there is no single authority introducing LTC services for all older people, including those with mild disability. The multiple budget sources for LTC services started to prevail. Except for 20% of local authorities using the social medical insurance fund solely, the remaining authorities set up two (40%) or three and more (40%) grant schemes, including medical insurance funds, financial assistance, employers’ contributions, personal payments, and welfare lottery funds. The 2016 guidance defines the standard insurance contribution to LTC services as 70% of the total cost. However, only one third of local authorities set a higher payment rate than this standard; almost half (46.7%) of them has lowered their service cost.

Table 2.

Characteristics and features of LTCI policies across 15 pilot authorities.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CITIES | COVERAGE | SERVICE BENEFICIARIES | FUND SOURCES | PAYMENT RATES | MEDICAL CARE & SENIOR SERVICES | SUPPLY OPTIONS | PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP | BENEFIT SCOPE | |||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| SMALL | MEDIUM | LARGE | SMALL | MEDIUM | LARGE | ONE | TWO | THREE/OVER | LOW | STANDARD | HIGH | ONE | TWO | THREE | ONE | TWO | THREE | SINGLE RESPONSIBILITY | JOINT WORK | SMALL | MEDIUM | LARGE | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chengde | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Changchun | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Qiqihaer | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shanghai | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nantong | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Suzhou | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ningbo | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anqing | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shangrao | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Qingdao | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jingmen | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Guangzhou | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chongqing | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chengdu | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shihezi | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tatol

(%) |

8

(53.3%) |

1

(6.7%) |

6

(40.0%) |

13

(86.7%) |

2

(13.3%) |

0

(0.0%) |

3

(20.0%) |

6

(40.0%) |

6

(40.0%) |

7

(46.7%) |

3

(20.0%) |

5

(33.3%) |

8

(53.3%) |

3

(20.0%) |

4

(26.7%) |

1

(6.7%) |

9

(60.0%) |

5

(33.3%) |

5

(33.3%) |

10

(66.7%) |

6

(40.0%) |

2

(13.3%) |

7

(46.7%) |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

There are many inconsistencies and inequities in the types of benefits. Medical care & senior services normally consist of daily care services and daily care related nursing & rehabilitation services. The results found that 73.3% of local authorities simply provided the first type (53.3%) or the second type (20.0%) for older people in need of LTC. Only 4 local authorities included both types of services to be covered by benefits. National government encourages local authorities to integrate institution-, community-, home-based facilities for the supply of LTC services. However, this proposal has not been widely accepted, just one third of local authorities have done it. The rest authorities relied on either the institution (6.7%) or a combination of institutions and communities (60%). The introduction of private sectors enables older people to select service providers and to improve service effectiveness. 66.7% of local authorities have developed joint work between commercial insurance companies and social medical insurance institutions, with the former being responsible for the insured persons’ requirements and the latter carrying out supervision over the procedures. On the other hand, there are still 5 authorities just empowering a public management institution for the delivery of LTCI. With respect to the benefit scope, there are two opposite ways at the local level. 40% of pilot authorities only insured LTC services, while another 46.7% authorities expanded LTCI to other health-related services including medicines, treatment, assistive equipment, care beds, nursing care and so on.

Discussion

Research results showed that local policies for the implementation of LTCI in China were fragmented with a range of existing issues. Firstly, because of an aging population and their longevity extension, there was a significant shortage of LTC services for older people, leading to a new social risk [61]. Secondly, local government was empowered to carry out their own policies in accordance with local aging process and economic development [62]. Thirdly, China’s social policy implementation is often confined to path dependence. Reforms of social security system, including basic living allowance, low-rent house, endowment insurance and medical insurance, has been piloted by local government since 1990s [63,64]. After summarising and analysing the characteristics of successful local pilots, central government then published national policies to promote their implementation across the country. In order to protect older people’s rights and to ensure effective use of LTC resources, local authorities require integrating policies in a directional and functional way.

Based on the theoretic framework for policy integration, service coverage and service beneficiaries are the key benchmark against which performance of LTCI policies is assessed. On average, only 40% of residences have been covered by LTCI services, with only 13% of moderately disabled older people except for severely disabled older people receiving LTC services. There is a need to expand LTCI services, covering all residences in urban and rural areas [65]. Besides, older people with mental and physical disability, no matter moderately and severely, should receive health care and nursing services [66]. This requires central government to compare local LTCI programmes, identify positive experiences, and integrate local priorities into national policy for multiple functionalities [67].

Funding streams and payment rates setting have significant effects on LTC insurability and sustainability. Similar to other countries, the primary source of financing LTC services in China is national expenditures. However, evidence from the pilot authorities showed that direct public subsidies towards LTC were very limited. To expand LTCI programmes nationally, it is necessary to build multiple streams of funding from individuals, enterprises, public resources and private donations [13]. Local government should pool all these financial resources to achieve a better balance between the public and private funds [11]. For those vulnerable elderly households, the government should provide means-tested benefits along with LTCI to improve social governance [68]. Meanwhile, to avoid any moral hazard effects and maintain relatively appropriate social protection, a 10% to 30% co-payment can be introduced like German and Japan for individuals to take certain responsibility for LTC services. In this regard, local government should seek coherent cross-sectoral policy instruments to perform their cooperative functions.

Types of medical care & senior services and their supply systems are important features of an effective LTCI policy framework. Table 2 found that only one third of pilot authorities have provided home-based LTC. However, most older people desire to live longer in their own homes; aging in place contributes to not only a better support from family but also a reduced burden to the social care system. In fact, favourable effects of LTC policies in many countries are largely dependent upon informal family caregiving [69]. Therefore, it is vital to develop home-based LTC services, especially daily care services and rehabilitation therapy services [70,71]. This requires local authorities to create interdependencies between different policies on ageing at home, aging in community and aging in institution, and then coordinate them. In this coordination process, there should be combination of formal services and informal care with caring as a focus, nursing as a priority and medicing as a supplement [72]. More specifically, community medical resources are delivered to support older people stay healthy at home; sickbed is installed in the house for family members with severely chronic diseases; severely disabled older people are allowed to live in care-based or nursing-based institutions [73].

PPP and administrative capacity are fundamental to strength the LTCI system. In western countries, the provision of LTC services has traditionally been a cooperation between profit-making sectors and non-profit sectors. For instance, in England non-profit institutions and private for-profit have been cooperated in LTC provision for years, with 89% of care at home and 94% of beds in residential settings being provided by private sectors [47]. Similarly, in Ireland, the severe shortage of public resources brought about marketisation and privatisation of LTC services, with around 75% of LTC services contributed from private commercial providers [74]. In contrast, findings from pilot authorities showed that PPP for LTC provision in China was very limited and only commercial insurance companies were involved on the private side. To address this, it is important for national and local government to integrate LTC policies, to coordinate different functional departments, and to encourage private and non-governmental organizations working in partnership with public institutions.

Conclusion

The introduction of LTCI made innovative changes to the provision of aging services in China. This social insurance mode is selected because of the existing five social insurance systems in China, just like the LTCI act implemented in Germany and Japan [75]. The pilot of LTCI policies is a crucial approach to social governance in China.

The LTCI programmes have been piloted for five years across China and produced some substantial progress in the support for the elderly. However, there are still some serious problems. This study established a clear picture of policy fragmentations in key aspects, including service coverage, service beneficiaries, funding sources, payment rates, medical services & senior services, supply options, PPP and management capacity. The major issue with the LTCI system is not only the cost but budget allocation [19]. To address this issue, there needs to be a range of strategic initiatives.

First, it is necessary to integrate service concept, which requires the vertical integration of policy makers and the horizontal integration of service providers. In other words, attentions should transfer from the life course to a consistent preventive action [76], from forced care to independent living [77], from traditional daily care to a combination of daily care and rehabilitation services [40].

Second, it is important to pool all financial sources together. This requires the integration of funding from both the civil administration and the disabled persons’ federation, the optimised allocation of various welfare subsidies for the elderly and the disabled, and the avoidance of full reliance on medical insurance funds [78].

Third, another key thing is to integrate the process of service delivery. The LTC system should strengthen the horizontal integration of rehabilitation services and hospice care, establish a competitive PPP service system [66], especially induce private suppliers and arrange a monitoring and managing system like Israel [79].

At last, there needs to be an integration of service beneficiaries. The sustainability of the LTCI system is subject to “who will benefit”, but not all disabled elderly people can benefit in China. Therefore, there is usually a compromise. More importantly, formal care and informal care should be integrated to establish a service user-oriented delivery system and to meet the LTC needs of older people with chronic diseases or severe disabilities [80]. This can secure equity and efficiency in LTC interventions.

Funding Statement

This study was financially supported by National Office for Philosophy and Social Science of China (Grant no.: 18AGL018) and by Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Office (Grant no.: 21NDJC136YB).

Abbreviations

| WHO: | World Health Organization |

| LTC: | long-term care |

| LTCI: | long-term care insurance |

| ICOPE: | integrated care for older people |

| PPP: | public-private partnership |

Reviewers

Dr Adekunle Sabitu Oyegoke, School of Built Environment, Engineering and Computing, Leeds Beckett University, UK.

One anonymous reviewer.

Funding information

This study was financially supported by National Office for Philosophy and Social Science of China (Grant no.: 18AGL018) and by Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Office (Grant no.: 21NDJC136YB).

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- 1.Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Three Departments Released the Fourth Survey Results on the Living Conditions of Older People in Urban and Rural Areas of China. Bejing: MCAPRC; 2016. http://jnjd.mca.gov.cn/article/zyjd/xxck/201610/20161000886652.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. China Country Assessment Report on Ageing and Health; 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/194271/9789245509318-chi.pdf;jsessionid=C9BC37A9539B634A884F201B051AE6A1?sequence=5.

- 3.Costa-Font J. (eds.). Reforming long-term care in Europe. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. DOI: 10.1002/9781444395556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rattan SI. Ageing – a biological perspective. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 1995; 16(5): 439–508. DOI: 10.1016/0098-2997(95)00005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin K. Modern biological theories of aging. Aging and Disease, 2010; 1(2): 72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu YZ, Dang JW. Blue book of ageing: China report of the development on silver industry. Beijing: China Social Science Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Da Roit B, Le Bihan B, Österle A. Long-term care policies in Italy, Austria and France: variations in cash-for-care schemes. Social Policy & Administration, 2007; 41(6): 653–671. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00577.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hua ZS, Liu ZY, Meng QF, Luo XG, Huo BF, Bian YW. National strategic needs and key scientific issues of intelligent pension services. Bull Natural Science Foundation of China, 2016; 30(6): 535–545. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell CJ, Ikegami N, Kwon S. Policy learning and cross-national diffusion in social long-term care insurance: Germany, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. International Social Security Review, 2009; 62(4): 63–80. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-246X.2009.01346.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.General Office of the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. Guidance on Establishing Long-Term Care Insurance System in The Pilot Cities; 2016. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-07/08/content_5089283.htm.

- 11.Mosca I, Van Der Wees PJ, Mot ES, Wammes JJ, Jeurissen PP. Sustainability of long-term care: puzzling tasks ahead for policy-makers. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2017; 6(4): 195–205. DOI: 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santana S. Reforming Long-term Care in Portugal: Dealing with the multidimensional character of quality. Social Policy & Administration, 2010; 44(4): 512–528. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00726.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee JC, Done N, Anderson GF. Considering long-term care insurance for middle-income countries: comparing South Korea with Japan and Germany. Health Policy, 2015; 119(10): 1319–1329. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikegami N. Financing long-term care: lessons from Japan. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2019; 8(8): 462–466. DOI: 10.15171/ijhpm.2019.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villalobos Dintrans P. Long-term care systems as social security: the case of Chile. Health Policy and Planning, 2018; 33(9): 1018–1025. DOI: 10.1093/heapol/czy083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seok JE. Public long-term care insurance for the elderly in Korea: design, characteristics, and tasks. Social Work in Public Health, 2010; 25(2): 185–209. DOI: 10.1080/19371910903547033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss J, Gruber J. Using knowledge for control in fragmented policy arenas. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 1984; 3(2): 225–247. DOI: 10.2307/3323934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kontopoulos Y, Perotti R. Government fragmentation and fiscal policy outcomes: evidence from OECD countries. In: Poterba JM, Von Hagen J. (eds.). Fiscal Institutions and Fiscal Performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roubini N, Sachs J. Government spending and budget deficits in the industrial countries. Economic Policy, 1989; 8: 99–132. DOI: 10.2307/1344465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volkerink B, Haan DJ. Fragmented government effects on fiscal policy: new evidence. Public Choice, 2001; 109(3–4): 221–242. DOI: 10.1023/A:1013048518308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson G. The challenge of financing care for individuals with multimorbidities. In OECD (eds.). Health Reform. France: OECD Publishing, 72–98(27); 2011. DOI: 10.1787/9789264122314-6-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmarcher MM, Oxley H, Rusticelli E. Improved health system performance through better care coordination. OECD Health Working Papers 30. France: OECD Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SH, Kim DH, Kim WS. Long-term care needs of the elderly in Korea and elderly long-term care insurance. Social Work in Public Health, 2010; 25(2): 176–184. DOI: 10.1080/19371910903116979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. The Milbank Quarterly, 1999; 77(1): 77–110. DOI: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunwoo D, Lee Y, Kim J, Yoo K. A Study on establishment of the 1st basic plan to improve public long-term care system for the elderly. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Challis D. Community care of elderly people: bringing together scarcity and choice, needs and costs. Financial Accountability & Management, 1992; 8(2): 77–95. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0408.1992.tb00206.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berchtold P, Peytremann-Bridevaux I. Integrated care organizations in Switzerland. International Journal of Integrated Care, 2011; 11. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chon YA. Qualitative exploratory study on the service delivery system for the new long-term care insurance system in Korea. Journal of Social Service Research, 2013; 39(2): 188–203. DOI: 10.1080/01488376.2012.744708 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lioyd J, Wait S. Integrated care: a guide for policymakers. London: Alliance for Health & the Future; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyles A. Alzheimer’s disease: the specter of fragmented policy and financing. Clinical Therapeutics, 2008; 30(1): 192–194. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glendinning C. Home care in England: markets in the context of under-funding. Health & Social Care in the Community, 2012; 20(3): 292–299. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deeming C. Addressing the social determinants of subjective wellbeing: the latest challenge for social policy. Journal of Social Policy, 2013; 42(3): 541–565. DOI: 10.1017/S0047279413000202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Department of Health UK. Use of resources in adult social care. London: Department of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hardy B, Mur-Veemanu I, Steenbergen M, Wistow G. Interagency services in England and the Netherlands: a comparative study of care development and delivery. Health Policy, 1999; 48: 87–105. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-8510(99)00037-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penny B. Policy framework for integrated care for older people developed by the carmen network. London: King’s Fund; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker BB, Collins CA. Developing an integrated primary care practice: strategies, techniques, and a case illustration. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 2009; 65(3): 268–280. DOI: 10.1002/jclp.20552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida K, Kawahara K. Impact of a fixed price system on the supply of institutional long-term care: a comparative study of Japanese and German metropolitan areas. BMC Health Services Research, 2014; 14: 48. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le Bihan B, Martin C. Reforming long-term care policy in France: private–public complementarities. Social Policy & Administration, 2010; 44(4): 392–410. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00720.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kodner DL. The quest of integrated system of care for frail older persons. Aging clinical and experimental research, 2002; 14(4): 307–313. DOI: 10.1007/BF03324455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Billings J. What do we mean by integrated care? A European interpretation. International Journal of Integrated Care, 2005; 13(5): 13–20. DOI: 10.1108/14769018200500035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Streefland P, Chowdhury M. The long-term role of national non-government development organizations in primary health care: lessons from Banglades. Health Policy and Planning, 1990; 5(3): 261–266. DOI: 10.1093/heapol/5.3.261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elmer S, Kilpatrick S. Using project evaluation to build capacity for integrated health care at local levels. International Journal of Integrated Care, 2006; 14(5): 6–13. DOI: 10.1108/14769018200600033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Homecare Association UK. An overview of the UK domiciliary care sector. London: UKHCA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schut FT, Van Den Berg B. Sustainability of comprehensive universal long-term care insurance in the Netherlands. Social Policy & Administration, 2010; 44(4): 411–35. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00721.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rothgang H. Social insurance for long-term care: An evaluation of the German model. Social Policy & Administration, 2010; 44(4): 436–60. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00722.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spasova S, Baeten R, Coster S, Ghailani D, Peña-Casas R, Vanhercke B. Challenges in Long-term Care in Europe: A Study of National Policies 2018. European Commission; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization. Integrated care for older people. Geneva: WHO; 2017. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/ageing/health-systems/icope/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Health Organization. Framework on integrated, people-centred health services. Geneva: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Carvalho IA, Epping-Jordan J, Pot AM, Kelley E, Toro N, Thiyagarajan JA, Beard JR. Organizing integrated health-care services to meet older people’s needs. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2017; 95(11): 756. DOI: 10.2471/BLT.16.187617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Auschra C. Barriers to the integration of care in inter-organisational settings: a literature review. International journal of integrated care, 2018; 18(1). DOI: 10.5334/ijic.3068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briggs AM, Araujo de Carvalho I. Actions required to implement integrated care for older people in the community using the World Health Organization’s ICOPE approach: a global Delphi consensus study. PLoS One, 2018; 13(10): e0205533. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiu TY, Yu HW, Goto R, Lai WL, Li HC, Tsai ET, Chen YM. From fragmentation toward integration: a preliminary study of a new long-term care policy in a fast-aging country. BMC geriatrics, 2019; 19(1): 1. DOI: 10.1186/s12877-019-1172-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hawkes N. Integrated care. British Medical Journal, 2009; 338. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.b1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Briggs AM, Valentijn PP, Thiyagarajan JA, de Carvalho IA. Elements of integrated care approaches for older people: a review of reviews. BMJ open, 2018; 8(4): e021194. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, Bruijnzeels MA. Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 2013; 13: e010. DOI: 10.5334/ijic.886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McShane MK, Cox LA. Issuance decisions and strategic focus: the case of long-term care insurance. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 2009; 76(1): 87–108. DOI: 10.1111/j.1539-6975.2009.01289.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aromataris E, Pearson A. The systematic review: an overview. AJN The American Journal of Nursing, 2014; 114(3): 53–8. DOI: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000444496.24228.2c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2003; 96(3): 118–21. DOI: 10.1177/014107680309600304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schutt RK. Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research. Sage publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morgan F. The treatment of informal care-related risks as social risks: an analysis of the English care policy system. Journal of Social Policy, 2018; 47(1): 179–96. DOI: 10.1017/S0047279417000265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Montinola G, Qian Y, Weingast BR. Chinese style: the political basis for economic success in China. World Politics, 1995; 48(1): 50–81. DOI: 10.1353/wp.1995.0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heilmann S. Policy experimentation in China’s economic rise. Studies in Comparative International Development, 2008; 43(1): 1–26. DOI: 10.1007/s12116-007-9014-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu W, Li W. Divergence and convergence in the diffusion of performance management in China. Public Performance & Management Review, 2016; 39(3): 630–654. DOI: 10.1080/15309576.2015.1138060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitchell SO, Piggott J, Shimizutani S. An empirical analysis of patterns in the Japanese long-term care insurance system. The Geneva Risk and Insurance Review, 2008; 33: 694–709. DOI: 10.1057/gpp.2008.25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rothgang, H. Social Insurance for long-term care: an evaluation of the German model. Social Policy & Administration, 2010; 44(4): 436–460. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00722.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang W, He AJ, Fang L, Mossialos E. Financing institutional long-term care for the elderly in China: a policy evaluation of new models. Health Policy and Planning, 2016; 31(10): 1391–1401. DOI: 10.1093/heapol/czw081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Comas-Herrera A, Pickard L, Wittenberg R, Malley J, Kind D. The long-term care system for the elderly in England. Brussels: ENEPRI Research Report No. 74; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Colombo F, Llena-Nozal A, Mercier J, Tjadens F. Help wanted? Providing and paying for long-term care. Geneva: OECD; 2011. DOI: 10.1787/9789264097759-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bolin K, Lindgren B, Lundborg, P. Informal and formal care among single-living elderly in Europe. Health Economics, 2008; 17(3): 393–409. DOI: 10.1002/hec.1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.King D, Pickard L. When is a carer’s employment at risk? Longitudinal analysis of unpaid care and employment in midlife in England. Health & Social Care in the Community, 2013; 21(3): 303–314. DOI: 10.1111/hsc.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Houde SC, Gautam R, Kai I. Long-term care insurance in Japan: implications for U.S. long-term care policy. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 2007; 33(1): 7–13. DOI: 10.3928/00989134-20070101-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yong V, Saito Y. National long-term care insurance policy in Japan a decade after implementation: some lessons for aging countries. Ageing International, 2012; 37: 271–284. DOI: 10.1007/s12126-011-9109-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.European Commission. Joint Report on Health Care and Long-Term Care Systems and Fiscal Sustainability and its country reports, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs and Economic Policy Committee (Ageing Working Group), Brussels: European Commission; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nicholas B. Long-term care: a suitable case for social insurance. Social Policy & Administration, 2010; 44(4): 359–374. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00718.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walker A. Why the UK needs a social policy on ageing. Journal of Social Policy, 2018; 47(2): 253–273. DOI: 10.1017/S0047279417000320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rachel H. Integrated care-foundation trust or social enterprise? International Journal of Integrated Care, 2007; 15(1): 20–23. DOI: 10.1108/14769018200700004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Theobald H, Chon Y. Home care development in Korea and Germany: The interplay of long-term care and professionalization policies. Social Policy & Administration, 2020; 54(5): 615–629. DOI: 10.1111/spol.12553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ajzenstadt M, Rosenhek Z. Privatisation and new modes of state intervention: the long-term care programme in Israel. Journal of Social Policy, 2000; 29(2): 247–262. DOI: 10.1017/S0047279400005961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Burchardt T, Jones E, Obolenskaya P. Formal and informal long-term care in the community: interlocking or incoherent systems? Journal of Social Policy, 2018; 47(3): 479–503. DOI: 10.1017/S0047279417000903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]