Abstract

There is a need for timely, accurate diagnosis, and personalised management in lung diseases. Exhaled breath reflects inflammatory and metabolic processes in the human body, especially in the lungs. The analysis of exhaled breath using electronic nose (eNose) technology has gained increasing attention in the past years. This technique has great potential to be used in clinical practice as a real-time non-invasive diagnostic tool, and for monitoring disease course and therapeutic effects. To date, multiple eNoses have been developed and evaluated in clinical studies across a wide spectrum of lung diseases, mainly for diagnostic purposes. Heterogeneity in study design, analysis techniques, and differences between eNose devices currently hamper generalization and comparison of study results. Moreover, many pilot studies have been performed, while validation and implementation studies are scarce. These studies are needed before implementation in clinical practice can be realised. This review summarises the technical aspects of available eNose devices and the available evidence for clinical application of eNose technology in different lung diseases. Furthermore, recommendations for future research to pave the way for clinical implementation of eNose technology are provided.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12931-021-01835-4.

Keywords: Electronic nose, Breath analysis, Respiratory medicine, Personalised medicine, Machine learning, Sensor technology

Background

The field of pulmonary medicine has rapidly evolved over the last decades, with increasing knowledge about pathophysiology and aetiology leading to better targeted treatment strategies. Nevertheless, many chronic lung diseases have non-specific, often overlapping symptoms, which delays the diagnostic process and timely start of adequate treatment. Moreover, even specific disease entities can be very heterogeneous with varying phenotypes, and thus disease courses and optimal treatment strategies vary per patient. Accurate, non-invasive, real-time diagnostic tools and biomarkers to predict disease course and response to therapy are currently lacking in most lung diseases, but are indispensable to achieve a personalised approach for individual patients.

An emerging tool that has the potential to meet this need is an electronic nose (eNose). This device ‘smells’ exhaled breath for clinical diagnostics, a concept probably as old as the field of medicine itself. Exhaled breath contains thousands of molecules, also known as volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These VOCs can be divided into compounds derived from the environment (exogenous VOCs) and compounds that are the result of biological processes in the body (endogenous VOCs). Endogenous VOCs can be associated with normal physiology, but also with pathophysiological inflammatory or metabolic activity [1, 2]. Identification of individual VOCs using techniques as gas chromatography or mass spectrometry is a specific but time-consuming exercise. An eNose can be used in real-time to recognise patterns of VOCs and has therefore potential as point-of-care tool in clinical practice.

The aim of this paper is to review the current clinical evidence on eNose technology in lung disease, regarding diagnosis, monitoring of disease course and therapy evaluation. In addition, technical aspects and available eNose devices are discussed.

eNose technology

In the time of Hippocrates, it was already acknowledged that exhaled breath can provide information about health conditions [3]. For instance, a sweet acetone breath odour indicates diabetes, a fishy smell suggests liver disease, and wounds with smell of grapes point towards pseudomonas infections [4]. Initial breath analysis studies were performed using gas chromatography or mass spectrometry. Throughout the last decades, more techniques were developed for breath analysis, for example ion mobility spectrometry, selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry and laser spectrometry [5]. Although these techniques became more advanced during the years and are very precise in identifying individual VOCs, they are very complex, laborious and thus not suitable as a real-time clinical practice tool.

Exhaled breath analysis by use of eNose technology is recently gaining increasing attention. An eNose is defined as “an instrument which comprises of an array of electronic-chemical sensors with partial specificity and an appropriate pattern recognition system, capable of recognising simple or complex odours” [6]. Sensors are used in eNoses to generate a singular response pattern. The sensors can generally be divided into three categories: electrical, gravimetric, and optical sensors. Each type responds to analytes (i.e. VOCs) in a specific way, and all types have a high sensitivity. Each sensor has advantages and disadvantages, without one type being superior in general. Electrical sensors consist of an electronic circuit connected to sensory materials. Upon binding with specific analytes, an electrical response is provided [7–10]. Consequently, a variation in electrical property of the sensor surface can be detected. Electrical sensors are low-cost, but are sensitive to temperature changes and have a limited sensor life [11]. Gravimetric (or mass sensitive) sensors label analytes based on changes in mass, amplitude, frequency, phase, shape, size, or position. Gravimetric sensors contain a complex circuitry and are sensitive to humidity and temperature [11]. Finally, optical sensors detect a change in colour, light intensity or emission spectra upon analyte binding. Optical sensors are insensitive to environmental changes, but are the most technically complex sensor-array systems and are not portable due to breakable optics and components. Due to the high complexity, they are more expensive than the other sensor types [11]. For each type of sensor, a more in depth explanation can be found in the Additional file 1.

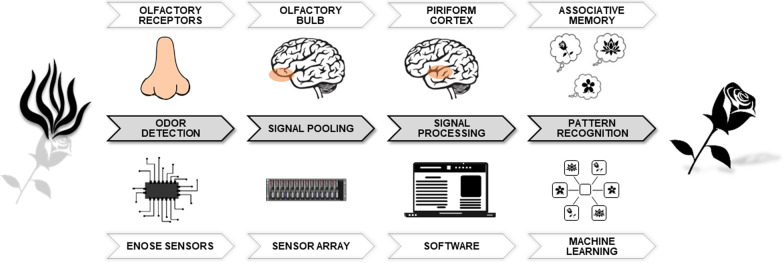

Detection and recognition of odours by an eNose is similar to the functioning of the mammalian olfactory system (Fig. 1). First, an odour is detected (by olfactory receptors in a human nose or eNose sensors), which sends off various signals (to the cortex or software). Then, these signals are pooled together and processed into a pattern. This pattern can be recognised as a particular smell (e.g. a flower) [12]. As a result, an eNose can differentiate between diseases by analysing and comparing the smelled ‘breathprints’ (i.e. VOC patterns) with those previously learned. The devices are hand-held, patient friendly, easy-to-use and feasible as point-of-care test.

Fig. 1.

Schematic comparison of eNose technology and the olfactory system [12]

Analysis methods

To analyse eNose breathprints, pattern recognition by machine learning is most commonly used. A machine learning model uses algorithms which automatically improve due to experience with previously presented data. These models are in general established using a five step process: data collection, data preparation, model building, model evaluation, and model improvement. Machine learning is categorised into unsupervised, supervised, and reinforcement learning [13]. In supervised learning, the algorithms are trained with labelled data input, the desired output is thus known. On the contrary, unsupervised learning allows the algorithm to recognise patterns in the data, and groups data without providing labels. Lastly, reinforcement learning encompasses the training of the machine learning models to generate decision sequences. The latter is not used in the eNose studies reviewed in this paper.

Several machine learning models have been proposed as appropriate algorithms for modelling complex nonlinear relationships in medical research data, such as breathprints. These models include, amongst others, artificial neural networks (mimicking the structure of animal brains to model functions), ensemble neural networks (many neural networks working together to solve a problem), and support vector machines (SVM, creating a hyperplane which allows the modelling of highly complex relationships) [14, 15]. A comparison between eNose studies show that SVM algorithm is most frequently used (10 out of 17 studies in 2019) [15]. Possibly, this is due to the fact that this is the easiest model to use for researchers new to machine learning. Another factor can be the existence of many programming languages with well-supported libraries for SVM algorithms. SVM also possesses a high accuracy, is not very prone to overfitting, and is not overly influenced by noisy data [15]. Nonetheless, there is no consensus about the optimal model for breathprint analysis.

Available eNoses

Various eNose devices have been developed and studied in different lung diseases. Table 1 provides an overview of the specifications of devices used in studies reviewed in this paper. The choice of an eNoses device may, among others, depend on the measurement setting. For example for the BIONOTE, Cyranose 320, PEN3, and Tor Vergata eNoses the exhaled breath is captured into sample bags or cartridges which makes it possible to collect on-site and store samples for later analyses. In other settings, it could be preferable that the eNose is easily portable, like the Aeonose. The SpiroNose is the only eNose that is capable of adjusting for disturbances from ambient air using its external sensors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of available eNoses

| Aeonose | BIONOTE | Cyranose 320 | PEN3 | SpiroNose | Tor Vergata | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | The eNose company, Zutphen, the Netherlands | Campus Bio-Medico University, Rome, Italy | Sensigent, California, United States (previously known as: Smith Detections) | Airsense Analytics GmbH, Schwerin, Germany | Breathomix, Leiden, the Netherlands (previously produced by: Comon Invent) | Tor Vergata University, Rome, Italy |

| Working Principle (i.e. sensors) | Electrical sensors | Gravimetric sensors | Electrical sensors | Electrical sensors | Electrical sensors | Gravimetric sensors |

| Sensing material | MOS | QCM | Conducting polymer | MOS | MOS | QCM |

| Array composition | 1 array; 3 sensors | 1 array; 7 sensors operating at 4 different temperatures | 1 array; 32 different polymers | 1 array; 10 different sensors | 4 exhaled breath and 4 reference arrays; 7 different sensors per array | 1 array; 8 sensors |

| Breath collection | Tidal breathing straight into eNose | Tidal breathing into Pneumopipe cartridge | Exhalation into sample bag | Exhalation into sample bag | Exhalation straight into eNose | Exhalation into sample bag |

| NA | 3 min tidal breathing | 5 min tidal breaths, deep inhale, exhalation | 5 min tidal breathing, deep in- and exhalation | 5 tidal breaths, deep inhale, breath hold, slow exhalation | Deep in- and exhalation | |

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Image source | www.enose.nl | Rocco et al. 2016 [16] | www.sensigent.com/products/cyranose.html | www.airsense.com/sites/default/files/flyer_pen.pdf | www.breathomix.com | Tor Vergata University |

An overview of specifications of eNose devices used in studies reviewed in this paper. eNose prototypes are not included. BIONOTE biosensor-based multisensorial system for mimicking nose tongue and eyes, eNose electric nose, MOS metal oxide semiconductor, PEN portable electronic nose, QCM quartz crystal microbalance. Images are used with approval of the eNose companies

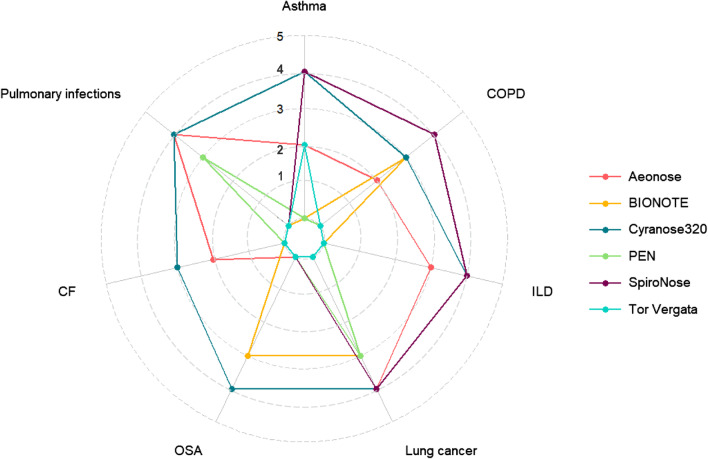

The stage of development towards a clinically implemented tool differs substantially per device and disease. Before clinical implementation, each specific eNose has to be tested as a proof of concept and consecutively in substantial cohorts for each specific disease. Subsequently, data validation and clinical implementation needs to be assessed in real-life cohorts. To give more insights in the stage of development for each eNose per lung disease, we divided studies in five different stages: (1) proof of concept study; (2) cohort size of diseased participants less than fifty; (3) cohort size of diseased participants equal or more than fifty; (4) study cohort with an external validation cohort; (5) evaluation of clinical implementation. An overview of the progress per eNose and disease is visualised in Fig. 2. To the best of our knowledge, none of the devices are currently used in clinical pulmonology practice.

Fig. 2.

Radar plot of development stages per eNose and disease. Studies were divided into five different stages: (1) proof of concept study; (2) cohort size of diseased participants less than fifty; (3) cohort size of diseased participants equal or more than fifty; (4) study cohort with an external validation cohort; (5) evaluation of clinical implementation. The highest stage reached for each eNose per lung disease is displayed. eNose prototypes are not included. BIONOTE biosensor-based multisensorial system for mimicking nose tongue and eyes, CF cystic fibrosis, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ILD interstitial lung disease, OSA obstructive sleep apnoea, PEN portable electronic nose.

Current clinical application

On 21 October 2020, a systematic literature search was performed in the databases Embase, Medline (Ovid), and Cochrane Central. Search terms and selection criteria are described in the Additional file 2. Table 2 provides an overview of design and results of all studies in this review.

Table 2.

Literature overview eNose technology in lung disease

| Study participants | Outcome measures | Results | eNose | Statistical breathprint analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | |||||||||

| Dragonieri, 2007 [18] |

n = 20 asthma • n = 10 mild • n = 10 severe n = 20 HC • n = 10 old • n = 10 young |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Mild vs young HC CVV 100% |

Severe vs old HC CVV 90% |

Mild vs severe CVV 65% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||

| Fens 2009 [19] |

n = 20 asthma n = 30 COPD n = 20 non-smoking HC n = 20 smoking HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

COPD vs asthma CVA 96% |

COPD vs smoking HC CVA 66% |

Non-smoking vs smoking HC Not significant |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

| Lazar 2010 [20] |

n = 10 asthma • induction of bronchoconstriction with methacholine or saline n = 10 controls |

Disease course | Bronchoconstriction causes no significant change in breathprint | Cyranose 320 | PCA; mixed model analysis | ||||

| Montuschi 2010 [21] |

n = 27 asthma n = 24 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

eNose only Acc 87.5% |

eNose + FeNO Acc 95.8% |

Tor Vergata | PCA; feed-forward neural network | |||

| Fens 2011 [26] |

Training: [19] n = 20 asthma n = 20 COPD |

Validation: n = 60 asthma • n = 21 fixed obstruction • n = 39 classic n = 40 COPD |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Validation: Classic asthma vs COPD Sens 85% Spec 90% AUC 0.93 (0.84–1.00) Acc 83% |

Validation: Fixed asthma vs COPD Sens 91% Spec 90% AUC 0.95 (0.87–1.00) Acc 88% |

Validation: Fixed vs classic asthma No significant difference |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | |

| Van der Schee 2013 [22] |

n = 25 asthma n = 20 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Before OCS Sens 80.0% Spec 65.0% AUC 0.766 ± 0.14 |

After OCS Sens 84.0% Spec 80% AUC 0.862 ± 0.12 |

Before OCS (FeNO only) AUC 0.738 ± 0.15 |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||

|

n = 18 asthma • maintenance ICS, stop ICS (4 weeks) and OCS (2 weeks) |

Therapeutic effect |

OCS responsive vs not Sens 90.9% Spec 71.4% AUC 0.883 (± 0.16) |

|||||||

|

n = 25 asthma • maintenance ICS, stop ICS (4 weeks) and OCS (2 weeks) • n = 13 Loss of control (LOC) |

Disease course |

LOC vs no LOC Sens 90.9% Spec 71.4% AUC 0.814 ± 0.17 |

Correlation sputum eos—breathprint R = 0.601 |

||||||

| Plaza 2015 [30] |

n = 24 eosinophilic asthma n = 10 neutrophilic asthma n = 18 paucigranulocytic asthma |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Neutro vs pauci Sens 94% Spec 80% AUC 0.88 CVA 89% |

EoS vs neutro Sens 60% Spec 79% AUC 0.92 CVA 73% |

EoS vs pauci Sens 55% Spec 87% AUC 0.79 CVA 74% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||

| Brinkman 2017 [32] |

n = 22 asthma, induced LOC • maintenance ICS, stop ICS (8 weeks) and restart ICS |

Disease course |

Baseline vs LOC Acc 95% |

LOC vs recovery Acc 86% |

Correlation sputum eos—breathprint Not significant |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

| Bannier 2019 [23] |

n = 20 asthma (age > 6 years) n = 22 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 74% Spec 74% AUC 0.79 |

Aeonose | ANN | ||||

| Brinkman 2019 [31] |

n = 78 severe asthma • n = 51 longitudinal follow-up |

Clustering |

3 clusters (baseline), acc 93% Differences: chronic OCS use, percent serum eosinophil and neutrophil count |

Follow-up (18 months) n = 21 cluster stable n = 30 migrated |

Cyranose 320, Tor Vergata, Comon Invent | PCA; Ward clustering; Non-hierarchical K-means clustering; PLS-DA; PAM; Topological data analysis | |||

| Cavaleiro Rufo 2019 [34] |

n = 64 suspected asthma (age 6–18 years) • n = 45 asthma • n = 29 persistent • n = 16 intermittent • n = 19 no asthma |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Asthma vs no asthma Sens 77.8% Spec 84.2% AUC 0.81 (0.69–0.93) Acc 79.7% |

Persistent vs no asthma Sens 79.7% Spec 68.6% AUC 0.81 (0.70–0.92) Acc 79.7% |

Intermittent vs no asthma Not significant |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; Hierarchical clustering | ||

| Dragonieri 2019 [24] |

Training: n = 14 AAR n = 14 rhinitis n = 14 HC |

Validation: n = 7 AAR n = 7 rhinitis n = 7 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: AAR vs HC AUC 0.87 (0.70–0.97) CVA 75.0% |

Validation: AAR vs HC AUC 0.77 (0.62–0.93) CVA 67.4% |

Validation: AAR vs rhinitis AUC 0.92 (0.84–1.00) CVA 83.1% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | |

| Abdel-Aziz 2020 [118] |

Training: n = 486 atopic asthma (age > 4 years) |

Validation: n = 169 atopic asthma (age > 4 years) |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: AUC 0.837–0.990 Sens, spec and acc only visually available |

Validation: AUC 0.18–0.926 Sens, spec and acc only visually available |

Cyranose 320, Tor Vergata, Comon Invent, SpiroNose | PLS-DA; adaptive least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; gradient boosting machine | ||

| Farraia 2020 [28] |

Training: n = 121 asthma suspected (age > 6 years) |

Validation: n = 78 asthma suspected (age > 6 years) |

Clustering |

Training: 3 clusters (hierarchic), differences: food/drink intake 2 h prior to sampling, percentage of asthma diagnosis in group, PEF%, age < 12 y |

Validation: 3 clusters (hierarchic), differences: food/drink intake 2 h prior to sampling | Cyranose 320 | Unsupervised hierarchic clustering; Non-hierarchical K-means clustering; PAM | ||

| Tenero 2020 [25] |

n = 28 asthma (age 6–16 years) • n = 9 controlled • n = 7 partially controlled • n = 12 uncontrolled n = 10 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

HC + controlled vs. partially + uncontrolled Sens 79% Spec 84% AUC 0.85 (0.72–0.98) |

Cyranose 320 |

Penalized logistic regression PCA |

||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | |||||||||

| Fens 2011 [45] |

n = 28 GOLD I + II • airway inflammation (sputum eosinophil cationic protein and myeloperoxidase) |

Disease course |

Correlation eosinophil cationic protein and breathprint r = 0.37 |

Correlation myeloperoxidase and breathprint Not significant |

Airway inflammation vs no Sens 50–73% Spec 77–91% AUC 0.66–0.86 |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

| Hattesohl 2011 [37] |

n = 23 COPD (pure exhaled breath, PEB) n = 10 COPD (exhaled breath condensate, EBC) n = 10 HC (EBC, PEB) n = 10 AATd (EBC, PEB) |

Diagnostic accuracy |

COPD vs HC Sens 100% Spec 100% CVV PEB 67.6% CVV EBC 80.5% |

COPD vs AATd Sens 100% Spec 100% CVV PEB 58.3% CVV EBC 82.0% |

HC vs AATd Sens 100% Spec 100% CVV PEB 62.0% CVV EBC 59.5% |

Cyranose 320 | LDA | ||

|

n = 11 AATd COPD (PEB) • augmentation therapy |

Therapeutic effect |

Before vs 6 d after therapy Sens 100% Spec 100% CVV 53.3% |

|||||||

| Fens 2013 [42] | n = 157 COPD | Clustering |

4 clusters (acc 97.4%) Differences: airflow limitation, health related QoL, sputum production, dyspnoea, smoking history, co-morbidity, radiologic density, gender |

Cyranose 320 |

Hierarchical cluster analysis Non-hierarchical K-means clustering |

||||

| Sibila 2014 [41] |

n = 10 COPD bacterial colonised n = 27 COPD non-colonised n = 13 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Colonised vs non-colonised Sens 82% Spec 96% AUC 0.922 CVA 89% |

HC vs non-colonised Sens 81% Spec 86% AUC 0.937 CVA 83% |

HC vs colonised Sens 80% Spec 93% AUC 0.986 CVA 87% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||

| Cazzola 2015 [38] |

n = 27 COPD • n = 8 AECOPD ≥ 2 per year • n = 19 AECOPD < 2 per year n = 7 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

COPD vs HC Sens 96% Spec 71% CVA 91% |

AECOPD ≥ 2 vs < 2 per y Not significant |

Prototype (6 QMB sensors) | PLS-DA | |||

| Shafiek 2015 [39] |

n = 50 COPD • n = 17 sputum PPM growth n = 93 AECOPD • n = 42 sputum PPM growth n = 30 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

COPD vs HC Sens 70–72% Spec 70–73% |

COPD vs AECOPD no PPM Sens 89% Spec 48% (with PPM not significant) |

AECOPD PPM vs AECOPD no PPM Sens 88% Spec 60% |

Cyranose 320 | LDA; SLR | ||

|

n = 61 AECOPD • during and 2 months after recovery |

Disease course |

During vs recovery Sens 74% Spec 67% |

|||||||

| Van Geffen 2016 [46] |

n = 43 AECOPD • n = 18 with viral infection • n = 22 with bacterial infection |

Diagnostic accuracy |

With vs without viral infection Sens 83% Spec 72% AUC 0.74 |

With vs without bacterial infection Sens 73% Spec 76% AUC 0.72 |

Aeonose | ANN | |||

| De Vries 2018 [43] |

Training: n = 321 asthma/COPD |

Validation: n = 114 asthma/COPD |

Clustering |

5 clusters Differences: ethnicity, systemic eosinophilia/ neutrophilia, FeNO, BMI, atopy, exacerbation rate |

SpiroNose | PCA; Unsupervised Hierarchical clustering | |||

| Finamore 2018 [49] |

n = 63 COPD • n = 32 n6MWD worsened 1 year • n = 31 n6MWD stable or improved 1 year |

Disease course |

n6MWD change predicted by eNose Sens 84% Spec 88% CVA 86% |

n6MWD change predicted by eNose + GOLD Sens 81% Spec 78% CVA 79% |

BIONOTE | PLS-DA | |||

| Montuschi 2018 [50] |

n = 14 COPD • maintenance ICS, stop ICS (4 weeks) and restart ICS |

Therapeutic effect |

Maintenance vs restart ICS Change in 15 of 32 Cyranose sensors; 3 of 8 Tor Vergata sensors |

Maintenance vs restart ICS Spirometry + breathprint prediction model AUC 0.857 |

Cyranose 320, Tor Vergata | Multilevel PLS; KNN | |||

| Scarlata 2018 [44] |

n = 50 COPD • standard inhalation therapy (12 weeks) |

Therapeutic effect |

Baseline vs after 12 w Significant decline in VOCs |

BIONOTE | PLS-DA | ||||

| n = 50 COPD | Clustering |

3 clusters Differences: BODE index, number of comorbidities, MEF75, KCO, pH/pCO2 arterial blood |

Unsupervised K-means clustering | ||||||

| Van Velzen 2019 [47] |

n = 16 AECOPD • before, during and after recovery |

Disease course |

Before vs during Sens 79% Spec 71% CVA 75% |

During vs after Sens 79% Spec 71% CVA 75% |

Before vs after Sens 57% Spec 64% CVA 61% |

Cyranose 320, Tor Vergata, Comon Invent | PCA | ||

| Rodríguez-Aguilar 2020 [40] |

n = 116 COPD • n = 88 smoking, n = 28 household air pollution associated • n = 64 GOLD I-II, n = 52 GOLD III-IV n = 178 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

COPD vs HC Sens 100% Spec 97.8% AUC 0.989 Acc 97.8% (CDA), 100% (SVM) |

Smoking vs air pollution associated Not significant |

GOLD I–II vs GOLD III–IV Not significant |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA; SVM | ||

| Cystic fibrosis (CF) | |||||||||

| Paff 2013 [52] |

n = 25 CF n = 25 primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) n = 23 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

CF vs HC Sens 84% Spec 65% AUC 0.76 |

CF vs PCD Sens 84% Spec 60% AUC 0.77 |

Exacerbation CF Sens 89% Spec 56% AUC 0.76 |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

| Joensen 2014 [53] |

n = 64 CF • n = 14 pseudomonas infection n = 21 PCD n = 21 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

CF vs HC Sens 50% Spec 95% AUC 0.75 |

CF vs PCD Not significant |

Pseudomonas vs. non-infected CF Sens 71.4% Spec 63.3% AUC 0.69 (0.52–0.86) |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

| De Heer 2016 [54] |

n = 9 CF colonised A. fumigatus n = 18 CF not colonised |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 78% Spec 94% AUC 0.80–0.89 CVA 88.9% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||||

| Bannier 2019 [23] |

n = 13 CF (age > 6 years) n = 22 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 85% Spec 77% AUC 0.87 |

Aeonose | ANN | ||||

| Interstitial lung disease (ILD) | |||||||||

| Dragonieri 2013 [58] |

n = 31 sarcoidosis • n = 11 untreated • n = 20 treated n = 25 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Untreated vs HC AUC 0.825 CVA 83.3% |

Untreated vs treated CVA 74.2% |

Treated vs HC Not significant |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||

| Yang 2018 [59] |

Training: 80% of n = 34 pneumo-coniosis n = 64 HC |

Validation: 20% of n = 34 pneumo-coniosis n = 64 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: Sens 64.3–67.9% Spec 88.0–92.0% AUC 0.89–0.91 Acc 80.8–82.1% |

Validation: Sens 33.3–66.7% Spec 71.4–78.6% AUC 0.61–0.86 Acc 65.0–70.0% |

Cyranose 320 | LDA; SVM | ||

| Krauss 2019 [60] |

n = 174 ILD • n = 51 IPF • n = 25 CTD-ILD n = 33 HC n = 23 COPD |

Diagnostic accuracy |

IPF vs HC Sens 88% Spec 85% AUC 0.95 |

CTD-ILD vs HC Sens 84% Spec 85% AUC 0.90 |

IPF vs CTD-ILD Sens 86% Spec 64% AUC 0.84 |

Aeonose | ANN | ||

| Dragonieri 2020 [61] |

n = 32 IPF n = 36 HC n = 33 COPD |

Diagnostic accuracy |

IPF vs HC AUC 1.00 (1.00–1.00) CVA 98.5% |

IPF vs COPD AUC 0.85 (0.75–0.95) CVA 80.0% |

IPF vs COPD + HC AUC 0.84 CVA 96.1% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA; LDA | ||

| Moor 2020 [57] |

Training: n = 215 ILD • n = 57 IPF • n = 158 non-IPF n = 32 HC |

Validation: n = 107 ILD • n = 28 IPF • n = 79 non-IPF n = 15 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training + validation: ILD vs HC Sens 100% Spec 100% AUC 1.00 Acc 100% |

Training: IPF vs non-IPF ILD Sens 92% Spec 88% AUC 0.91 (0.85–0.96) Acc 91% |

Validation: IPF vs non-IPF ILD Sens 95% Spec 79% AUC 0.87 (0.77–0.96) Acc 91% |

SpiroNose | PLS-DA | |

| Lung cancer (LC) | |||||||||

| Machado 2005 [75] |

Training: n = 14 LC n = 20 HC n = 27 other lung disease |

Validation: n = 14 LC n = 30 HC n = 32 other lung disease |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: LC vs HC + other CVA 71.6% (CDA) |

Validation: LC vs HC + other Sens 71.4% Spec 91.9% Acc 85% (SVM) |

Cyranose 320 |

SVM PCA CDA |

||

| Hubers 2014 [71] |

Training: n = 20 LC n = 31 HC |

Validation: n = 18 LC n = 8 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: Sens 80% Spec 48% |

Validation: Sens 94% Spec 13% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

| Schmekel, 2014 [88] |

n = 22 LC • n = 10 survival > 1 year • n = 12 survival < 1 year n = 10 HC |

Disease course |

< 1 y vs HC R = 0.95–0.98 |

< 1 y vs > 1 y R = 0.86–0.97 |

Prediction model survival days R = 0.99 |

Applied Sensor AB model 2010 | PCA; PLS; ANN | ||

| McWilliams 2015 [68] |

n = 25 LC n = 166 smoking HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 84–96% Spec 63.3–81.3% AUC 0.84 |

Cyranose 320 | Classification and regression tree; DFA | ||||

| Gasparri 2016 [76] |

Training: n = 51 LC n = 54 HC |

Validation: n = 21 LC n = 20 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training + validation: Sens 81% Spec 91% AUC 0.874 |

Training: Sens 90% Spec 100% |

Validation: Sens 81% Spec 100% |

Prototype (8 QMB sensors) | PLS-DA | |

| Rocco 2016 [16] |

n = 100 (former) smokers • n = 23 LC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Detection LC Sens 86% Spec 95% AUC 0.87 |

BIONOTE | PLS-Toolbox; PLS-DA | ||||

| Van Hooren 2016 [81] |

n = 32 LC n = 52 head-neck SCC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 84–96% Spec 85–88% AUC 0.88–0.98 Acc 85–93% |

Aeonose | ANN | ||||

| Shlomi 2017 [67] |

n = 30 benign nodule n = 89 LC • n = 16 early stage LC • n = 53 EGFR tested (n = 19 mutation) |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Early stage LC vs benign Sens 75% Spec 93.3% Acc 87.0 |

EGFR mutation vs wild type Sens 79.0% Spec 85.3% Acc 83.0% |

Prototype (40 nanomaterial-sensors) | DFA | |||

| Tirzite 2017 [83] |

n = 165 LC n = 79 HC n = 91 other lung disease |

Diagnostic accuracy |

LC vs HC + other Sens 87.3–88.9% Spec 66.7–71.2% CVV 72.8% |

LC vs HC Sens 97.8–98.8% Spec 68.8–81.0% CVV 69.7% |

LC stages Not significant |

Cyranose 320 | SVM | ||

| Huang 2018 [70] |

Training: 80% of n = 56 LC n = 188 HC |

Validation: 20% of n = 56 LC n = 188 HC External: n = 12 LC n = 29 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Validation: LC vs HC Sens 100, 92.3% Spec 88.6, 92.9% AUC 0.96, 0.95 Acc 90.2, 92.7% |

External validation: LC vs HC Sens 75, 83.3% Spec 96.6, 86.2% AUC 0.91, 0.90 Acc 85.4, 85.4% |

Cyranose 320 | LDA; SVM | ||

| Van de Goor 2018 [73] |

Training: n = 52 LC n = 93 HC |

Validation: n = 8 LC n = 14 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: Sens 83% Spec 84% AUC 0.84 Acc 83% |

Validation: Sens 88% Spec 86% Acc 86% |

Aeonose | ANN | ||

| Tirzite 2019 [77] |

n = 119 LC smoker n = 133 LC non-smoker n = 223 HC + other lung disease • n = 91 smoking |

Diagnostic accuracy |

LC non-smoker vs HC + other Sens 96.2% Spec 90.6% |

LC smoker vs HC + other Sens 95.8% Spec 92.3% |

Cyranose 320 | LRA | |||

| Kononov 2020 [78] |

n = 65 LC n = 53 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 85.0–95.0% Spec 81.2–100% CVA 88.9–97.2% AUC 0.95–0.98 |

Prototype (6 MOS) | PCA; Logistic regression; KNN; Random forest; LDA; SVM | ||||

| Krauss 2020 [79] |

n = 91 LC active disease • n = 51 incident LC n = 29 LC complete response n = 33 HC n = 23 COPD |

Diagnostic accuracy |

LC active vs HC Sens 84% Spec 97% AUC 0.92 |

Incident LC vs HC Sens 88% Spec 79% AUC 89% |

Aeonose | ANN | |||

| Lung cancer—(non-)small cell lung cancer ((N)SCLC) | |||||||||

| Dragonieri 2009 [69] |

n = 10 NSCLC n = 10 COPD n = 10 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

NSCLC vs HC CVV 90% |

NSCLC vs COPD CVV 85% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | |||

| Kort 2018 [72] |

n = 144 NSCLC n = 18 SCLC n = 85 HC n = 61 suspected, LC excluded |

Diagnostic accuracy |

NSCLC vs HC Sens 92.2% Spec 51.2% AUC 0.85 |

NSCLC vs HC + LC excluded Sens 94.4% Spec 32.9% AUC 0.76 |

SCLC vs HC Sens 90.5% Spec 51.2% AUC 0.86 |

Aeonose | ANN | ||

| De Vries 2019 [87] |

Training: n = 92 NSCLC • n = 42 response • n = 50 no response |

Validation: n = 51 NSCLC • n = 23 response • n = 28 no response |

Therapeutic effect (anti-PD-1 therapy) |

Training: CVV 82% AUC 0.89 (0.82–0.96) |

Validation: AUC 0.85 (0.7–0.96) Sens 43% Spec 100% |

SpiroNose | LDA | ||

| Mohamed 2019 [80] |

n = 50 NSCLC n = 50 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 92.9% Spec 90% Acc 97.7% |

PEN3 | PCA; ANN | ||||

| Kort 2020 [74] |

n = 138 NSCLC n = 143 controls • n = 59 suspected, LC excluded • n = 84 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

NSCLC vs controls (eNose data only) Sens 94.2% Spec 44.1% AUC 0.75 |

NSCLC vs controls (multivariate) Sens 94.2–95.7% Spec 49.0–59.7% AUC 0.84–0.86 |

Aeonose | ANN; Multivariate logistic regression | |||

| Fielding 2020 [82] |

n = 20 bronchial SCC • n = 10 in situ • n = 10 advanced stage n = 22 laryngeal SCC • n = 12 in situ • n = 10 advanced stage n = 13 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

BSCC in situ vs HC Sens 77% Spec 80% Misclassification rate 28% |

BSCC vs LSCC adv Sens 100% Spec 80% Misclassification rate 10% |

Cyranose 320 | Bootstrap forest | |||

| Lung cancer—Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MPM) | |||||||||

| Chapman 2012 [86] |

Training: n = 10 MPM n = 10 HC |

Validation: n = 10 MPM n = 32 HC n = 18 benign ARD |

Diagnostic accuracy |

MPM vs HC Training: CVA 95% Validation: Sens 90% Spec 91% |

MPM vs ARD Validation: Sens 90% Spec 83.3% |

MPM vs ARD vs HC Validation: Sens 90% Spec 88% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | |

| Dragonieri 2012 [85] |

n = 13 MPM • internal validation with training set: n = 8, validation set: n = 5 n = 13 HC n = 13 AEx |

Diagnostic accuracy |

MPM vs HC Sens 92.3% Spec 69.2% AUC 0.893 CVA 84.6% Validation: AUC 0.83 CVA 85.0% |

MPM vs AEx Sens 92.3% Spec 85.7% AUC 0.917 CVA 80.8% Validation: AUC 0.88 CVA 85.9% |

MPM vs AEx vs HC AUC 0.885 CVA 79.5% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||

| Lamote 2017 [84] |

n = 11 MPM n = 12 HC n = 15 AEx n = 12 benign ARD |

Diagnostic accuracy |

MPM vs HC Sens 66.7% (37.7–88.4) Spec 63.6% (33.7–87.2) AUC 0.667 (0.434–0.900) Acc 65.2% (44.5–82.3) |

MPM vs benign ARD Sens 75.0% (45.9–93.2) Spec 64% (33.7–87.2) AUC 0.758 (0.548–0.967) Acc 48.9–85.6% (48.9–85.6) |

MPM vs benign ARD + AEx Sens 81.5% (63.7–92.9) Spec 54.5% (26.0–81.0) AUC 0.747 (0.582–0.913) Acc 73.7% (58.1–85.8) |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

| Pulmonary infections | |||||||||

| De Heer 2016 [100] |

n = 168 bottles with strain • n = 135 bacteria + yeast • n = 30 medium only • n = 62 mould (A. fumigatus and R. oryzae) |

Diagnostic accuracy (in vitro) |

Mould vs other Sens 91.9% Spec 95.2% AUC 0.970 (0.949–0.991) Acc 92.9% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||||

| Suarez-Cuartin 2018 [101] |

n = 73 bronchiectasis • n = 41 colonised (n = 27 pseudomonas) • n = 32 non-colonised |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Colonised vs non-colonised AUC 0.75 CVA 72.1% |

Pseudomonas vs other PPM AUC 0.96 CVA 89.2% |

Pseudomonas vs non-colonised AUC 0.82 CVA 72.7% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

| Pulmonary infections—Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) | |||||||||

| Hanson 2005 [104] |

n = 19 VAP (clinical pneumonia score, CPIS ≥ 6) n = 19 controls (CPIS < 6) |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Correlation CPIS -breathprint R2 = 0.81 |

Cyranose 320 | PLS | ||||

| Hockstein 2005 [105] |

n = 15 VAP (pneumonia score ≥ 7) n = 29 HC (ventilated) |

Diagnostic accuracy | Acc 66–70% | Cyranose 320 | KNN | ||||

| Humphreys 2011 [99] |

n = 44 VAP suspected • 98 BAL samples • Groups: gram-positive, gram-negative, fungi, no growth n = 6 HC (ventilated) |

Diagnostic accuracy (in vitro) |

Differentiation groups (LDA) Sens 74–95% Spec 77–100% Acc 83% |

Differentiation groups (cross-validation) Sens 56–84% Spec 81–97% Acc 70% |

Prototype (24 MOS) | PCA; LDA | |||

| Schnabel 2015 [106] |

n = 72 VAP suspected • n = 33 BAL + • n = 39 BAL− n = 53 HC (ventilated) |

Diagnostic accuracy |

BAL + VAP vs HC Sens 88% Spec 66% AUC 0.82 (0.73–0.91) |

BAL + vs BAL− VAP Sens 76% Spec 56% AUC 0.69 (0.57–0.81) |

DiagNose | Random Forest; PCA | |||

| Chen 2020 [15] |

Training: 80% of n = 33 VAP n = 26 HC (ventilated) |

Validation: 20% of n = 33 VAP n = 26 HC (ventilated) |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: AUC 0.823 (0.70–0.94) |

Validation: Sens 79% (± 8) Spec 83% (± 0) AUC 0.833 (0.70–0.94) Acc 0.81 (± 0.04) |

Cyranose 320 | KNN; Naive Bayes; decision tree; neural network; SVM; random forest | ||

| Pulmonary infections—Tuberculosis (TB) | |||||||||

| Fend 2006 [109] |

n = 188 TB n = 142 TB excluded |

Diagnostic accuracy (in vitro) |

Sens 89% (80–97) Spec 88% (85–97) |

Bloodhound BH-114 | PSA; DFA; ANN | ||||

| Bruins 2013 [107] |

Training: n = 15 TB n = 15 HC |

Validation: n = 34 TB n = 114 TB excluded n = 46 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: Sens 95.9% (92.9–97.7) Spec 98.5% (96.2–99.4) |

Validation: TB vs HC Sens 93.5% (91.1–95.4) Spec 85.3% (82.7–87.5) |

Validation: TB vs TB excl Sens 76.5% (57.98–88.5) Spec 74.8% (64.5–82.9) |

DiagNose | ANN | |

| Coronel Teixeira 2017 [108] |

Training: n = 23 TB n = 46 HC |

Validation: n = 47 TB n = 63 HC + asthma + COPD |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: Sens 91% Spec 93% |

Validation: Sens 88% Spec 92% |

Aeonose | Tucker 3–like algorithm; ANN | ||

| Mohamed 2017 [110] |

n = 67 TB n = 56 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 98.5% (92.1–100) Spec 100% (93.5–100) Accuracy 99.2% |

PEN3 | PCA; ANN | ||||

| Saktiawati 2019 [111] |

Training: n = 85 TB n = 97 HC + TB excluded |

Validation: n = 128 TB n = 159 TB excluded |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: Sens 85% (75–92) Spec 55% (44–65) AUC 0.82 (0.72–0.88) |

Validation: Sens 78% (70–85) Spec 42% (34–50) AUC 0.72 (0.66–0.78) |

Aeonose | ANN | ||

| Zetola 2017 [112] |

n = 51 TB n = 20 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 94.1% (83.8–98.8) Spec 90.0% (68.3–98.8) |

Prototype (QMB sensors) | PCA; KNN | ||||

| Pulmonary infections—Aspergillosis | |||||||||

| De Heer 2013 [102] |

n = 11 neutropenia • n = 5 probable/proven aspergillosis • n = 6 no aspergillus |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 100% (48–100) Spec 83.3% (36–100) AUC 0.933 CVA 90.9% (59–100) |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||||

| De Heer 2016 [54] |

n = 9 CF colonised A. fumigatus n = 18 CF not colonised |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 78% Spec 94% AUC 0.80–0.89 CVA 88.9% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | ||||

| Pulmonary infections—Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) | |||||||||

| Wintjens 2020 [114] |

n = 219 screened • n = 57 COVID-19 positive |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Sens 86% (74–93) Spec 54% (46–62) AUC 0.74 CVA 62% |

Aeonose | ANN | ||||

| Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) | |||||||||

| Greulich 2013 [89] |

n = 40 OSA n = 20 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

OSA vs HC Sens 93% Spec 70% AUC 0.85 |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||||

|

N = 40 OSA • 3 months CPAP ventilation |

Therapeutic effect |

Before vs after CPAP Sens 80% Spec 65% AUC 0.82 |

|||||||

| Incalzi 2014 [95] |

n = 50 OSA • 1 night CPAP ventilation |

Therapeutic effect | Change in breathprint (visually different, no statistical analysis) | BIONOTE | PCA; PLS-DA | ||||

| Dragonieri 2015 [90] |

n = 19 OSA n = 14 obese n = 20 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Obese OSA vs HC CVA% 97.4 AUC 1.00 |

Obese OSA vs obese CVA% 67.6 AUC 0.77 |

Obese vs HC CVA% 94.1 AUC 0.94 |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA; KNN | ||

| Kunos 2015 [96] |

n = 17 OSA n = 9 non-OSA sleep disorder n = 10 HC • 7AM and 7PM sample n = 26 HC –7AM sample |

Diagnostic accuracy |

OSA 7AM vs 7PM Significantly different |

Non-OSA or HC 7AM vs 7PM Not significantly different |

(Non-)OSA 7AM vs HC 7AM Significantly different Acc 77–81% |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

| Dragonieri 2016 [92] |

Training: n = 13 OSA n = 15 COPD n = 13 overlap |

Validation: n = 6 OSA n = 6 COPD n = 6 overlap |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: OSA vs overlap CVA 96.2% AUC 0.98 |

Validation: OSA vs overlap CVA 91.7% AUC 1.00 |

Validation: OSA vs COPD CVA 75% AUC 0.83 |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; CDA | |

| Scarlata 2017 [91] |

n = 40 OSA • n = 20 hypoxic n = 20 obese n = 20 COPD n = 56 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

OSA vs HC Acc 98–100% |

Non-hypoxic vs hypoxic OSA Acc 60–80% |

HC vs COPD Acc 100% |

BIONOTE | PLS-DA | ||

| Other—Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) | |||||||||

| Bos 2014 [115] |

Training: n = 40 ARDS n = 66 HC |

Validation: n = 18 ARDS n = 26 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Training: Sens 95% Spec 42% AUC 0.72 |

Validation: Sens 89% Spec 50% AUC 0.71 |

Cyranose 320 | Sparse-partial least square logistic regression | ||

| Other—Lung transplantation (LTx) | |||||||||

| Kovacs 2013 [117] |

n = 16 LTx recipients n = 33 HC |

Diagnostic accuracy |

LTx recipients vs HC Sens 63% Spec 75% AUC 0.825 |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; Linear regression | ||||

| Therapeutic effect |

Correlation breathprint—tacrolimus levels R = -0.63 |

Cyranose 320 | PCA; Linear regression | ||||||

| Other—Pulmonary embolism (PE) | |||||||||

| Fens 2010 [116] |

n = 20 PE • n = 7 comorbidity n = 20 PE excluded • n = 13 comorbidity |

Diagnostic accuracy |

Comorbidity: PE vs excluded Acc 65% AUC 0.55 |

No comorbidity: PE vs excluded Acc 85% AUC 0.81 |

No comorbidity: PE vs excluded (breathprint + Wells) AUC 0.90 |

Cyranose 320 | PCA | ||

An overview of eNose technology studies in lung diseases. Studies are divided per diagnosis and displayed in chronological order. Study results shown in sensitivity/specificity, AUC and CVA (if available). In case of a training and validation set, participant numbers and results of both set are shown. All presented results are statistical significant (p < 0.05) unless stated otherwise

AATd alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, acc accuracy, AUC area under the curve, AAR extrinsic asthma with allergic rhinitis, AEx asbestos exposure, ANN artificial neural network, ARD benign asbestos related disease, BMI body mass index, CDA canonical discriminant analysis, CVA/CVV cross-validated accuracy/value, d days, DFA discriminate function analysis, EBC exhaled breath condensate, AECOPD acute COPD exacerbation, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, eos eosinophils, FeNO exhaled nitric oxide test, FVC forced vital capacity, GOLD global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease, HC healthy control (not suspected for studied disease, not diagnosed with other pulmonary disease), ICS inhaled corticosteroids, IPF idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, KNN k-nearest neighbours, LDA linear discriminant analysis, MOS metal oxide sensor, n6MWD normalised six minute walking distance, OCS oral corticosteroids, PAM partitioning around medoids, PCA principal component analysis, PEB pure exhaled breath, PLS-DA partial least squares discriminant analysis, PPM potentially pathogenic microorganism, QMB quartz microbalance, QoL quality of life, ROC receiver operator characteristics, SCC squamous cell carcinoma (B bronchial, L laryngeal), sens sensitivity, SLR Sensor Logic Relations, spec specificity, SVM support vector machines, TLC total lung capacity

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic lung disease characterised by reversible airflow obstruction with airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. Common symptoms, such as cough, chest tightness, shortness of breath and wheezing, are variable in severity and often non-specific [17]. Various studies, both in children and adults, showed that eNose technology can differentiate asthma patients from healthy controls with a good accuracy [18–25]. Two studies also demonstrated that breathprints of asthma patients were significantly different than breathprints of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients [19, 26]. Interestingly, two studies reported better performance of eNose technology than conventional investigations (spirometry or an exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) test) for detecting asthma. These studies were performed in patients with an established asthma diagnosis [21, 22]. Diagnostic performance further increased when eNose technology was combined with a FeNO test (accuracy 95.7%) [21]. Moreover, even after loss of control and reaching stable disease with oral corticosteroids (OCS) treatment eNose technology could differentiate asthma from healthy controls, while the diagnostic value of FeNO decreased. In the same study, breathprint significantly predicted response to subsequent OCS treatment, while sputum eosinophils, FeNO values and, hyperresponsiveness did not [22].

The existence of multiple asthma pheno- and endotypes with different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms is increasingly acknowledged [27]. In recent years, many eNose studies have attempted to identify different clusters of asthma patients, using both supervised and unsupervised methods [28–31]. For example, supervised clustering for eosinophilic, neutrophilic and paucigranulocytic phenotypes revealed significant differences in breathprints between groups [30]. One study identified three clusters using unsupervised breathprint analysis in a group of severe asthmatic patients, corresponding with different inflammatory profiles. During follow-up, 30 of 51 patients migrated to another cluster; migration was associated with changes in sputum eosinophil count [31]. Two other longitudinal studies showed changes in breathprint when asthma control was lost after withdrawal of corticosteroids in previously stable asthma patients, and also after recovery [22, 32]. A pilot study, in which bronchoconstriction was induced in stable asthma patients, found that changes in airway calibre did not alter breathprints. Moreover, breathprints remained stable during the day in individual patients [20]. This implies that inflammatory processes and not (acute) airway obstruction influence breathprints. Overall, these findings suggest that eNose technology is a promising tool for phenotyping and monitoring asthmatics. Longer follow-up studies are required to examine whether cluster-migration or change in breathprint are also related to actual clinical course.

A currently ongoing study is evaluating whether eNose technology can be used to predict response to monoclonal antibody therapy (NCT03988790).

Paediatric asthma

In general, the diagnosis of asthma in children is challenging. Lung function tests are often difficult to perform and do not always provide a diagnosis. Interestingly, a study in 45 children demonstrated that eNose measurements were fairly well repeatable, both in healthy and asthmatic participants [33].

Moreover, two studies showed that eNose technology distinguishes children with asthma from healthy controls [23, 25, 34]. An eNose seemed to be more accurate for diagnosing asthma than spirometry with bronchodilation only [34]. Also, uncontrolled asthma could be differentiated from controlled asthma and healthy controls [25]. Furthermore, eNose technology accurately distinguished children with persistent asthma from healthy controls, but not the ones with intermittent asthma [34]. This was possibly due to more airway inflammation reflected in the breathprints of persistent asthmatics. Hence, eNose technology could potentially facilitate easier and earlier diagnosis of asthma in children, and guide therapy in clinical practice. However, large validation studies focusing on diagnosing asthma in children are currently lacking.

COPD

Although COPD is one of the major causes of death worldwide, epidemiological studies indicate that it remains largely underdiagnosed [35]. COPD is a complex, heterogeneous disease with several phenotypes, which can overlap with asthma and pulmonary infections, among others. Furthermore, the diagnosis is delayed in patients whose symptoms are attributed to (undiagnosed) heart failure [36]. Hence, there is an unmet clinical need for accurate timely diagnosis. Also better disease course prediction and therapy guidance is warranted.

Several studies have evaluated the ability of eNose technology to diagnose COPD. Exhaled breath analysis discriminated between COPD and (smoking) healthy controls with an accuracy of 66–100% [19, 37–41]. Even though these are promising results, most studies were relatively small and lacked a validation cohort. Several studies aimed to distinguish subgroups within COPD by performing unsupervised analyses on breathprint data [42–44]. De Vries et al. performed unsupervised cluster analysis in a combined group of asthma and COPD patients [43]. Interestingly, they identified and validated five clusters which mainly differed based on clinical and inflammatory characteristics (eosinophil and neutrophil count) rather than diagnosis. Two other studies identified 3–4 unsupervised clusters based on breathprint data. The clusters differed regarding several clinical and demographic features [42, 44]. However, in both studies, clusters were determined by different clinical parameters, showing the need for further (validation) studies. A recent study indicated that breathprints of patients with COPD associated with air pollution did not differ from smoking-associated COPD [40]. Also, no differences in breathprint between Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage I-II versus GOLD stage III-IV were detected in another study [40]. The breathprint of patients with smoking-related COPD and patients with alpha-1-antitripsin, however, could be distinguished with an accuracy of 82% in a small single-centre study [37].

eNose technology can theoretically be useful in early detection of inflammation and acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD), as inflammatory processes influence breathprints. This hypothesis was confirmed in a cross-sectional study evaluating the association of breathprints with different inflammation markers in sputum; eNose breathprints highly correlated with inflammatory activity [45]. In patients with an AECOPD, presence of viral and bacterial infection was accurately detected by an eNose [46]. In another group of AECOPD patients, patients with colonisation of potentially pathogenic microorganisms had a significantly different breathprint than AECOPD patients that were not colonised. Besides, AECOPD patients’ breathprints differed from stable COPD patients without microorganism colonisation [39]. Stable COPD patients with bacterial colonisation were also significantly different from those without (area under the curve (AUC) 0.922) [41]. Two prospective longitudinal studies indicated that the breathprint before, during and after recovery of an AECOPD differed [39, 47]. Confirming these results in larger cohort studies might lead the way to use breathprints for earlier detection and (targeted) treatment of infections and AECOPDs. This is interesting as treatment may improve outcomes and prevent hospitalizations [48].

Regarding prognostic value of eNose technology, one study demonstrated that eNose data correlated better to change in 6-min walking distance over one year, than the current GOLD classification [49]. A few studies evaluated the effect of initiation and withdrawal of inhalation medication on breathprints. Two studies found significant changes in breathprint after start of inhalation therapy [44, 50]. A designed multidimensional model, combining eNose technology with spirometry, gave a better indication of treatment response (AUC 0.857) than spirometry only (AUC 0.561) [50]. This small pilot study shows the potential of integrating eNose technology in standard practice. However, it remains to be elucidated whether eNose technology can serve as a marker for therapy compliance of inhaled medication.

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is associated with bronchiectasis, recurrent infectious exacerbations, and progressive deterioration of lung function due to exacerbations [51].

A few studies using different eNoses showed that patients with CF could accurately be distinguished from healthy controls and asthma patients based on their breathprint [23, 52, 53]. Two studies showed conflicted results regarding differentiation of CF from primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) patients, a bronchiectatic lung disease that mimics symptoms of CF [53]. While Paff et al. showed that CF and PCD could be adequately discriminated, Joensen et al. found no significant differences [52, 53]. This was possibly due to methodological differences, such as different breath collection methods and a more heterogeneous patient population in the latter study. Furthermore, eNose technology adequately discriminated between patients with and without exacerbations, with and without chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonisation, and patients with and without Aspergillus fumigatus colonisation [52–54]. It would be of great interest to investigate whether early stage respiratory infections and exacerbations can also be detected and eventually be predicted by eNose technology. This will possibly increase the chance of successful eradication and slowing down pulmonary function decline.

Interstitial lung disease

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a heterogeneous group of relatively uncommon diseases causing fibrotic and/or inflammatory changes in interstitial lung tissue. Disease course and treatment strategies widely vary for different ILDs, and even within individual ILDs disease course often varies. Diagnosis is based on integration of clinical data with imaging and if needed pathology data. Diagnosis is often complex and diagnostic delays are common [55, 56]. eNose technology has the potential to replace invasive procedures, and aid the diagnostic process to facilitate timely and accurate diagnosis.

A large single centre cohort, including various ILDs, found that breathprints of ILD patients could be distinguished from healthy controls with 100% accuracy. Results were confirmed in a validation cohort [57]. A few other studies compared individual ILDs with healthy controls and COPD patients [58–61]. Breathprints of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), ILD associated with connective tissue disease and pneumoconiosis were significantly different from healthy controls [59–61]. In sarcoidosis patients, the breathprint of patients with untreated sarcoidosis differed from healthy controls, implying that eNose technology may be used for initial diagnosis. This study found that breathprints of treated sarcoidosis patients were not significantly different from healthy controls, but the number of participants was small [58]. Comparing different ILDs, eNose technology distinguished IPF from non-IPF ILD patients with an accuracy of 91% in both training and validation cohort. Exploratory analyses indicated that individual ILDs can also be discriminated adequately [57]. However, groups were relatively small and, thus, results should be validated and confirmed in larger cohorts. A currently ongoing large multicentre study is investigating the potential of eNose technology to identify individual diseases, predict disease course, and response to treatment in fibrotic ILDs (NCT04680832).

Lung cancer

Worldwide, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths and has the highest incidence of all cancer types. More than 80% of patients suffering from lung cancer are former or current tobacco smokers [62]. Early diagnosis is clearly associated with better outcomes, and lung cancer screening has shown to reduce mortality [63, 64]. Nevertheless, early diagnosis remains challenging, since initial clinical presentation often overlaps with COPD or other smoking-related diseases, and symptoms often only appear in late stages [65]. Low-dose CT scan is currently the best available tool for screening. However, this type of screening is only cost-effective in a selected group of former and current smokers [66]. Also, differentiation of benign from malignant nodules is not possible with CT scan results; therefore, detected nodules warrant further invasive investigations. eNose could possibly serve as non-invasive and less costly screening tool to identify malign pulmonary neoplasms. Two studies used eNose technology in high-risk patients enrolled for lung cancer screening. Both studies found a higher specificity for detecting lung cancer with eNose compared to low-dose CT scan; thus, the use of eNose technology as screening tool can potentially reduce the false-positive rate and prevent unnecessary (invasive) testing [16, 67]. It is important to note that not all lesions classified as benign were histologically proven in these studies.

Whether an eNose can differentiate lung cancer patients from healthy controls, patients with benign lung nodules or (former) smokers, has been investigated in different cohorts. All studies in (non-) small cell lung cancer ((N)SCLC) showed significant results, albeit with a wide range in reported sensitivity (71–99%) and specificity (13–100%) [68–80]. Smoking status of participants did not seem to influence accuracy of an eNose for detecting cancer [77]. One small study showed that patients with and without an EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) mutation had distinct breathprints [67]. It has not been evaluated whether eNoses can recognise specific types of lung cancer in a cohort with different subtypes. Recognition of subtypes seems plausible, as differentiation of lung cancer from head-neck cancer was possible with eNose technology [81, 82]. eNose technology did not discriminate between different stages of lung cancer [83]. One recent study in NSCLC combined eNose data with relevant clinical parameters (such as age, number of pack years, and presence of COPD), and showed a higher accuracy for lung cancer detection than using eNose data only. These results highlight the potential of eNose technology as additional diagnostic procedure [74]. Some small studies indicated that eNose technology was also able to differentiate patients suffering from malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) and healthy controls. Differentiation of MPM from benign asbestosis disease and asymptomatic asbestos exposure had a high sensitivity too [84–86].

Prediction of response to therapy is investigated for anti-programmed death (PD)-1 receptor therapy in NSCLC patients. Breathprints were collected before start of pembrolizumab or nivolumab therapy. Exhaled breath data could predict which patients would respond to therapy with an AUC of 0.89, confirmed in a validation cohort. By setting a cut-off value to obtain 100% specificity, the investigators were able to detect 24% of non-responders to anti-PD-1 therapy. In this regard, eNose seems to be more accurate than the currently used biomarker PD-L1 [87]. Another study is currently registered for recruiting until July 2021 and will evaluate the effect of immunotherapy on breathprints of exhaled breath and sweat in lung cancer patients (NCT03988192).

Schmekel et al. investigated the ability of eNose to predict prognosis in patients with end stage lung cancer. They collected breathprints before start and several times after start of palliative chemotherapy and applied different prediction models. Patients with less than one year survival and more than one year survival could be separated based on breathprint [88]. The authors suggest to use this eNose-based prediction for choosing a certain treatment strategy, but this needs confirmation in studies first.

Obstructive sleep apnoea

At the moment, the gold standard for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is (poly)somnography which is a costly and time-consuming test. eNose technology has been investigated as an alternative modality to diagnose this condition and assess treatment effect.

It was shown that breathprints from OSA patients and healthy controls can be distinguished reliably [89–91]. However, it remains questionable whether breathprints distinguishes true OSA, or if the breathprint is just a reflection of a metabolic syndrome or underlying inflammation caused by obesity. In one of the studies this question was more apparent as groups were not matched for body mass index [89]. Dragonieri et al. found that eNose technology did discriminate obese patients with and without OSA, with moderate accuracy [90]. Nevertheless, another study could not confirm those results [91].

Other researchers investigated OSA, OSA-COPD overlap syndrome and COPD. OSA could be distinguished from the overlap syndrome, but eNose technology could not discriminate well between the overlap syndrome and COPD. Also here it is not clear whether true OSA can be detected or other factors, such as COPD, are picked up [91, 92]. Whether included patients also suffer from heart failure is not clearly displayed in these studies, although it is known that many heart failure patients suffer from OSA and that heart failure might influence breathprint [93, 94].

The effects of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment in patients with OSA has also been studied. The breathprint of OSA patients changed significantly already after one night of CPAP treatment [95]. Significant difference in breathprint was also found before and after three months of CPAP treatment [89]. It remains to be elucidated what this change in breathprint indicates. Possibly, the alteration in breathprint could serve as a marker for metabolic success, therapeutic benefit or treatment adherence. Furthermore, it must be noted that the breathprints of patients with OSA differed between morning and evening [96]. Hence, diurnal variance must be taken into account when using an eNose for patients with OSA.

Pulmonary infections

Pathogenic micro-organisms, such as viruses, bacteria or fungi, can cause severe pulmonary infections. Identification of specific micro-organisms with sputum cultures can take up to several days, and is only possible if a specimen with sufficient quality is obtained. Specificity and sensitivity also depend on the causative micro-organism, experience of laboratory observer, and prior treatment [97]. Therefore, reported sensitivity of detecting bacteria in sputum culture ranges between 57 and 95%, and specificity between 48 and 87% [98]. Detection of specific micro-organisms using eNose technology can potentially reduce misuse of antibiotics and facilitate timely start of guided therapy.

Until now, two in vitro studies aimed to differentiate micro-organisms by analysing breathprints of their headspace air [99, 100]. Mould species were discriminated from other samples (bacteria, yeasts, and control medium) with a high accuracy (92.9%). Furthermore, different mould species seemed to have different breathprints [100]. Another study performed eNose analyses on bronchoalveolar lavage samples, and demonstrated accurate discrimination between Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, and samples without growth of micro-organisms [99]. In vivo, breathprints of bronchiectasis patients significantly differed between those colonised with Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and those colonised with other pathogenic micro-organisms or non-colonised [101]. For detection of aspergillus colonisation or invasive aspergillosis in specific patient groups (CF and neutropenic patients), studies revealed a high accuracy of eNose breathprint analysis [54, 102]. These studies did not include a validation cohort or healthy control group.

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a common nosocomial infection in ventilated patients and has an incidence and mortality around 9% [98, 103]. In most eNose studies, bacterial growth in sputum or a clinical pneumonia score was used to define VAP [15, 104–106]. Two studies showed that obtained breathprints highly correlated with a clinical pneumonia score, implying that eNose technology might be used to predict the probability of a VAP [104, 105]. Two case–control studies in patients with VAP and ventilated patients without pneumonia showed conflicting results; Schnabel and colleagues concluded that eNose technology lacked sensitivity and specificity, whereas a recently published study of Chen and colleagues found a good accuracy for detecting VAP [15, 106]. This shows the need for more research on this topic before eNose can be used to determine the need for more (invasive) diagnostics in ill patients, such as performing bronchoscopy.

In pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) patients, detection and screening with eNose technology has been studied in different countries and compared to different control groups [107–112]. As TB is the leading cause of death from an infection caused by a single micro-organism, and as it has a high prevalence in developing countries, establishing a fast non-invasive cheap screening tool is much needed [113]. In one study, eNose technology differentiated TB from non-TB quite accurately, suggesting that it can potentially serve as a screening tool. Detection of TB had a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 91% compared to positive cultures. This sensitivity and specificity exceeded Ziehl–Neelsen staining [109]. However, all studies with proven TB and healthy participants in the training cohort, had a lower accuracy when validating the results in a cohort also including suspected TB patients [107, 108, 111]. Thus, more research is necessary before eNose technology can be used as a population-wide screening tool.

Due to the Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, much research effort is being put in the evaluation of eNose technology as a fast and non-invasive tool for the detection of COVID-19 (NCT04475562, NCT04475575, NCT04558372, NCT04379154, NCT04614883, NL8694). To date, one study tested the accuracy of eNose technology for COVID-19 screening prior to surgery in non-symptomatic patients and found a negative predictive value up to 0.96. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction on a pharyngeal swab and antibody testing were used to confirm presence or absence of COVID-19 [114].

Other

A number of eNose studies have been performed in other lung diseases. In acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), eNose technology could discriminate between mechanically ventilated patients with and without ARDS, with moderate accuracy in a training and validation cohort [115].

One small proof-of-principle study has been performed in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism, defined as a high clinical probability according to the Well’s score or elevated D-dimer. Breathprints of non-comorbid patients with and without pulmonary embolism could be distinguished with an accuracy of 85%. However, in patients with comorbidities known to influence VOCs (e.g. cancer, diabetes) the accuracy dropped [116].

Finally, eNose technology could be useful for follow-up and monitoring lung transplant recipients. One study found a significant association between breathprint and plasma tacrolimus levels, suggesting that eNoses might be used for non-invasive therapeutic drug monitoring [117].

A clinical trial in lung transplant recipients is currently conducted (NL9251) looking at discrimination of stable lung transplant recipients, acute cellular rejection, and chronic lung allograft rejection.

Discussion

In the past decades, multiple eNoses have been developed and tested in numerous clinical studies for a wide spectrum of lung diseases. So far, the vast majority of studies evaluated the ability of eNose technology to distinguish lung diseases from healthy controls, and to discriminate between different diagnoses. A small number of studies have been performed for prognostic or therapeutic purposes, and only a handful of studies have focused on clustering patients by breathprint and identifying phenotypes. Results in lung diseases are overall very promising, but several issues should be addressed before eNoses can be implemented in daily clinical practice.

One of the issues is the use of various eNose devices with different qualifications, types of sensors and breath sample collection methods as summarised in Table 1. It is not possible to point out the best eNose device or select one optimal sensor type, as each setting, disease and research aim can require different features. For example, a portable device might be optimal for an acute care setting, direct sampling without collection bags might be useful in low resource areas and as point-of-care technique, and a device that corrects for ambient air will probably generate more comparable results in multicentre use and settings with unstable or varying environmental conditions.

Given important differences between the various devices, it is difficult to compare data of the different eNose devices. Hence, each eNose needs to be validated for every clinical application. This implies that knowledge about characteristics of eNose devices is essential before initiating eNose research, as the type of device cannot easily be changed during the trajectory of developing a clinical tool. Additionally, the influence of endogenous (e.g. comorbidities, ethnicity, age) and exogenous factors (e.g. smoking, nutrition, drug use, measurement environment) on breathprints needs to be further elucidated.

Furthermore, studies differ significantly with regards to study design (e.g. patient selection, number of participants, and presence of a validation cohort). As illustrated in Fig. 2, the majority of studies so far can be considered as pilot or exploratory studies, and have small numbers of participants. The most important goal of these studies is to test new hypotheses, which can be further assessed and confirmed in larger studies with external validation. However, these validation studies are not often conducted. This lack of validation is a major issue in development of a clinical useful breath biomarker, as breath analysis results are not always interchangeable between research settings due to a combination of the above mentioned factors. To ensure optimal outcomes, comparison and generalisability of eNose studies, the design and analysis methods should ideally be based on specific predefined research aims.

Moreover, most studies do not explain the rationale for choosing a certain machine learning model for analysing eNose data. This prevents insights in and discussion regarding the optimal analysis techniques and algorithms. Machine learning models are complex to execute and interpret, and if not used in the right way are prone for overfitting. To avoid inadequate modelling, data scientists should always be involved in these complex analyses and models should be validated independently to exclude overfitting. To allow for comparison of different modelling techniques, we recommend an extensive world-wide shared database per eNose with FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable) and open source data, including patient characteristics and other pre-test probabilities. This database would ensure optimal training, validation, and application of models.

Finally, a factor that hampers eNose implementation is the need for a strong gold standard to establish a diagnosis or to evaluate therapeutic effect. High quality data input is required for optimal validity when developing a new technique. Some of the diseases mentioned in this review lack a gold standard, and even if a gold standard does exist, there is always a range of uncertainty. There is a potential for unsupervised machine learning models in this regard, as such analyses could help to identify previously unrecognised phenotype clusters. Discovering such new clusters can help to generate hypotheses about the existence of unravelled disease subtypes or overlap between diagnoses, and might eventually guide new diagnostic standards.

In conclusion, eNose technology in the field of lung diseases is promising and at the doorstep of the pulmonologist’s office. To facilitate clinical implementation, we recommend conducting prospective multicentre trials including validation in external cohorts with a study design and analysis method relevant for the research aim, and sharing databases on open source platforms. If supported by sufficient evidence, research can subsequently be extended to clinical implementation studies, and finally, use in daily practice.

We believe that eNose technology has the potential to facilitate personalised medicine in lung diseases through establishing early, accurate diagnosis and monitoring disease course and therapeutic effects.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Sensor technology explained.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank dr. Sabrina T.G. Meertens-Gunput from the Erasmus MC Medical Library for developing and updating the search strategies.

Abbreviations

- AECOPD

Acute exacerbation of COPD

- AUC

Area under the curve

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CF

Cystic fibrosis

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COVID-19

Corona virus disease

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- eNose

Electronic nose

- FeNO

Exhaled nitric oxide

- GOLD

Global Initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease

- ILD

Interstitial lung disease

- IPF

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- MPM

Malignant pleural mesothelioma

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- OCS

Oral corticosteroids

- OSA

Obstructive sleep apnoea

- PCD

Primary ciliary dyskinesia

- PD

Programmed death

- SCLC

Small cell lung cancer

- TB

Tuberculosis

- VAP

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

- VOCs

Volatile organic compounds

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to conception and design of the study. NW, GN and IS conducted literature search and organised the database. NW and IS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the final manunscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Drs. Van der Sar reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study. Drs. Wijbenga has nothing to disclose. Drs. Nakshbandi has nothing to disclose. Dr. Aerts reports personal fees and non-financial support from MSD; personal fees from BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amphera, Eli Lilly, Takeda, Bayer, Roche, Astra Zeneca outside the submitted work. In addition, Dr. Aerts has a patent on allogenic tumor cell lysate licensed to Amphera, a patent combination immunotherapy in cancer pending, and a patent biomarker for immunotherapy pending. Dr. Manintveld has nothing to disclose. Dr. Wijsenbeek reports grants and other from Boehringen Ingelheim and Hoffman la Roche, and other from Galapagos, Novartis, Respivant, Savara outside the submitted work. All grants and fees were paid to dr Wijsenbeek’s institution. Dr. Hellemons has nothing to disclose. Dr. Moor reports grants and other from Boehringer-Ingelheim outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I. G. van der Sar and N. Wijbenga share first authorship

M. E. Hellemons and C. C. Moor share senior authorship

References

- 1.van der Schee MP, Paff T, Brinkman P, van Aalderen WMC, Haarman EG, Sterk PJ. Breathomics in lung disease. Chest. 2015;147(1):224–231. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van de Kant KDG, van der Sande LJTM, Jöbsis Q, van Schayck OCP, Dompeling E. Clinical use of exhaled volatile organic compounds in pulmonary diseases: a systematic review. Respir Res. 2012;13(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potter P. Hippocrates Vol VI. Diseases, internal affections. Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Španěl P, Smith D. Volatile compounds in health and disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14(5):455–460. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283490280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lourenço C, Turner C. Breath analysis in disease diagnosis: methodological considerations and applications. Metabolites. 2014;4(2):465–498. doi: 10.3390/metabo4020465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner JW, Bartlett PN. A brief history of electronic noses. Sens Actuators, B Chem. 1994;18(1):210–211. doi: 10.1016/0925-4005(94)87085-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Cheng S, Liu H, Hu S, Zhang D, Ning H. A survey on gas sensing technology. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2012;12(7):9635–9665. doi: 10.3390/s120709635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Q, Chen Z, Liu D, He Z, Wu J. Constructing E-nose using metal-ion induced assembly of graphene oxide for diagnosis of lung cancer via exhaled breath. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c00720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovalska E, Lesongeur P, Hogan BT, Baldycheva A. Multi-layer graphene as a selective detector for future lung cancer biosensing platforms. Nanoscale. 2019;11(5):2476–2483. doi: 10.1039/C8NR08405J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nag A, Mitra A, Mukhopadhyay SC. Graphene and its sensor-based applications: a review. Sens Actuators, A. 2018;270:177–194. doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2017.12.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Cheng S, Liu H, Hu S, Zhang D, Ning H. A survey on gas sensing technology. Sensors. 2012;12(7):9635–9665. doi: 10.3390/s120709635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos JP, J Lozano, Aleixandre M. Electronic noses applications in beer technology. Brewing Technology, Makoto Kanauchi. IntechOpen. 2017. 10.5772/intechopen.68822.

- 13.Shobha G, Rangaswamy S. Chapter 8—Machine learning. In: Gudivada VN, Rao CR, editors. Handbook of statistics. Elsevier: Amsterdam; 2018. pp. 197–228. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao YH, Wang ZC, Zhang FG, Abbod MF, Shih CH, Shieh JS. Machine learning methods applied to predict ventilator-associated pneumonia with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection via sensor array of electronic nose in intensive care unit. Sensors (Basel). 2019 doi: 10.3390/s19081866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CY, Lin WC, Yang HY. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia using electronic nose sensor array signals: solutions to improve the application of machine learning in respiratory research. Respir Res. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-1285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]