Urban ethnopharmacology is rapidly advancing and gaining significant attention throughout the world. In this review, we have presented the potential of urban ethnopharmacology and medicinal plants from the anthropologist and religious viewpoints. Additionally, the emergence and the present status of urban ethnopharmacology throughout the globe have been critically reviewed.

Keywords: Conservationenvironmentmedicinal plantsacred grovessustainabilityUrban ethnopharmacology

Abstract

The discipline ‘urban ethnopharmacology’ emerged as a collection of traditional knowledge, ancient civilizations, history and folklore being circulated since generations, usage of botanical products, palaeobotany and agronomy. Non-traditional botanical knowledge increases the availability of healthcare and other essential products to the underprivileged masses. Intercultural medicine essentially involves ‘practices in healthcare that bridge indigenous medicine and western medicine, where both are considered as complementary’. A unique aspect of urban ethnopharmacology is its pluricultural character. Plant medicine blossomed due to intercultural interactions and has its roots in major anthropological events of the past. Unani medicine was developed by Khalif Harun Al Rashid and Khalif Al Mansur by translating Greek and Sanskrit works. Similarly, Indo-Aryan migration led to the development of Vedic culture, which product is Ayurveda. Greek medicine reached its summit when it travelled to Egypt. In the past few decades, ethnobotanical field studies proliferated, especially in the developed countries to cope with the increasing demands of population expansion. At the same time, sacred groves continued to be an important method of conservation across several cultures even in the urban aspect. Lack of scientific research, validating the efficiency, messy applications, biopiracy and slower results are the main constrains to limit its acceptability. Access to resources and benefit sharing may be considered as a potential solution. Indigenous communities can copyright their traditional formulations and then can collaborate with companies, who have to provide the original inventors with a fair share of the profits since a significant portion of the health economy is generated by herbal medicine. Search string included the terms ‘Urban’ + ‘Ethnopharmacology’, which was searched in Google Scholar to retrieve the relevant literature. The present review aims to critically analyse the global concept of urban ethnopharmacology with the inherent plurality of the cross-cultural adaptations of medicinal plant use by urban people across the world.

Introduction

A confluence of anthropology, history, flow of traditional folklore through generations, palaeobotany, ethnomedicine and agronomy gave birth to the discipline of urban ethnopharmacology. Plant-based medicines have been popular prior to the arrival of modern synthetic drugs. The study of plants and plant-based products used by city and town dwellers is known as urban ethnopharmacology, as emphasized by the prefix ‘urban’. In a nutshell, the complicated relationships between people and plants in towns and cities form the basis of urban ethnopharmacology (Albuquerque et al., 2014; Hurrell and Pochettino, 2014; Anand et al., 2019; Mohammed et al., 2021; Datta et al., 2021). Urban botanical knowledge encompasses the consumption criteria of selection and production of plant products as well as the role of such knowledge in conservation (Hurrell and Pochettino, 2014). Lately, urban ethnopharmacology has been given crucial recognition, because a number of these traditionally used species are now vulnerable or critically endangered. International migrations lead to the expansion of traditional knowledge. When migrants settle in new cities or towns, they continue using their traditional remedies despite the availability of allopathic medicines and other conventional drugs. These dynamics of change upon being introduced from other communities into the existing ethnopharmacological implementations are explored and scrutinized in urban ethnopharmacology (Ceuterick et al., 2008; Pieroni and Privitera, 2014).

The fact that the literature available in this field is limited as this knowledge has traditionally been transmitted orally from one generation to the next and the only literature available is in the form of vernacular trivial ethnographic publications is a major constraint on the inclusion of traditional medicine in public health care practices (Petkeviciute et al., 2010). Some researchers, like Jacques, Barrau and Villamar, even consider ethnopharmacology as a section of anthropology, completely denying its existence in Botany (Albuquerque et al., 2014). Another limitation might be the study of only the economically important plants of particular regions by earlier ethnobotanists, vehemently omitting the plants that were found in that region but were utilized in other regions, a practice condemned by (Kroeber, 1920, Hurrell, 2014). An important feature of non-traditional botanical knowledge (Hurrell and Pochettino, 2014) is the availability of healthcare and other essential products to the underprivileged masses (Ocvirk et al., 2013; Vandebroek, 2013).

Intercultural medicine essentially involves ‘practices in healthcare that bridge indigenous medicine and western medicine, where both are considered as complementary’ (Mignone et al., 2007; Vandebroek, 2013). Cities are assumed to be systems where society and nature form a fused heterogeneous ecosystem within which synthetic and organic components are interrelated (Almada, 2010; Ladio and Albuquerque, 2014). Since ecology as a discipline flourished beforehand, it is important to analyse whether the order of anthropological usage of herbs matches with the predictions made by existing ecological theories and concepts, which can only be done if the ethnobotanical concepts and theories of various cultures are systematically recognized and developed into hypotheses that can be validated experimentally (Gaoue et al., 2017). One of the shortcuts is the usage of hybridization, where traditional medicine is reconstructed and integrated in different ways to form a product more compatible for urban markets (Ladio and Albuquerque, 2014). On the other hand, an important question arises: ‘Who will get the commercial benefits, these individual migrant groups or researchers, where the concept of intellectual property rights (IPR) is to be considered?’ (McGonigle, 2016). Some ethnobotanists consider children to be important preservers and informers of botanical knowledge, passing knowledge to each other, being remnants of practices no longer present in adults and trying newer species while playing in nature and interacting with the environment (Łuczaj and Nieroda, 2011), whereas another set of researchers believe the women as reservoirs of traditional botanical knowledge (TBK) (Voeks, 2007; Katiyar et al., 2012; Wayland and Walker, 2014). Urban ethnobotany, introduced lately as a terminology in modern ethnobotany, truly depicts the ‘pluricultural contexts in the urban agglomerations’ with its ostensible inclination to the traditional field work with a need for sustainable conservation of urban folklore. Earlier, only few works have been carried out on modern urban ethnobotany in Latin American and European contexts. The present review aims to comprehensively enumerate the practices of urban ethnopharmacology across the world with notes on sustainable utilization of medicinal plants and the inherent plurality of the cross-cultural adaptations of medicinal plant use by the urban people. This review, in true sense, is a piece of multidisciplinary endeavour where history, social studies, botany and ethical issues present their own shares of theoretical and methodological contributions.

Methodology

To retrieve the relevant records, a literature review of multiple disciplines from 1922 to 2019 was performed. The search string included the term ‘Urban’ + ‘Ethnopharmacology’, which was searched in Google Scholar, PubMed-NCBI, SpringerLink, Nature Publishing Group and other scientific databases. A detailed analysis of the articles presented in the references section was performed. Species names were checked against The Plant List 1.1 (2013), and family names follow the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV (Chase et al., 2016). All figures were constructed with the help of Microsoft Word, Autodesk or Sketchbook or were hand drawn. All tables and graphs were constructed by Microsoft Word and PowerPoint.

Through the eye of an anthropologist: the cross-cultural nature of urban ethnopharmacology

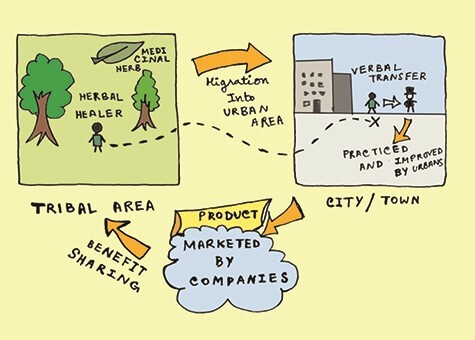

A unique aspect of urban ethnopharmacology is its pluricultural character. Pluriculturalism is a concept where individual identities result from participating in different cultures (Martínez et al., 2006). Multiculturalism is a theory where a community comprises of several ethnic groups, which may or may not have interactions. Pluriculturalism is based on the different interactions between these ethnic groups and new knowledge evolving from this exchange of values, traditions and resources. Multiculturalism forces uniformity and consistency and pluriculturalism allows for fluidity. Rural and small ethnic groups, who remain isolated from each other in their original habitats, tend to interact when they settle in urban areas (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The spread and development of urban ethnopharmacology.

These migrations lead to pluralism or the doctrine of multiplicity (Schneider, 2007), which is the co-existence of ideas and principles. Conflict of ideas creates more ideas and hence confluence and conflict of knowledge creates more knowledge. Therefore, contrasting ethnopharmacology leads to the advancement of ethnopharmacology and drug delivery. Historical events sometimes influence the propagation of ethnopharmacology as well. For example, an increased trend of using medicinal plants was seen in Europe during the aftermath of World War II as a result of the scarcity of resources (Pardo-de-Santayana et al., 2015). Unani medicine was developed by Khalif Harun Al Rashid and Khalif Al Mansur by translating Greek and Sanskrit works (Dahanukar and Thatte, 1997). Similarly, Indo-Aryan migration led to the development of Vedic culture resulted in Ayurveda (Childe, 1996). Greek rational medicine reached its summit when it travelled to Egypt (Longrigg, 2013). Garlic [Allium sativum L. (Amaryllidaceae)], a medicinal plant widely used in India for cardio-vascular disorders and lowering cholesterol, was found in the tombs of Egyptian pharaohs and Greek temples, used against respiratory disorders in Rome, flu in America, plague in Europe and for digestion in China and Japan. (Gebreyohannes and Gebreyohannes, 2013; Alqethami et al., 2017). The medicinal use of Neem [Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (Meliaceae)] started in China when Bhogar Sidhdhar travelled from India to teach in China (Kumar and Navaratnam, 2013). These historical studies clearly show that plant medicine blossomed due to intercultural interactions and has its roots in major anthropological events of the past. Archaeological evidence even showed that botanical products and cereal foods were consumed by prehistoric men (Day, 2013; Valamotiet al., 2019) and selective consumption of plants by monkeys were interestingly similar to the ones used by humans (Weiner, 1980) demonstrating the origins of ethnopharmacology even beyond human origins. The synthesis of these compounds by plant species were itself a result of interactions with microbes, pests and herbivores (Bhattacharya, 2014).

Urban ethnopharmacology: emergence and present status throughout the globe

In the past few decades, the ethnobotanical field studies proliferated, especially in the developed countries to cope with the increasing demands of population expansion (Pieroni and Privitera, 2014). All studies included selection of a specific site of study, its detailed description including its geography, geology, ethnic background, ecology, edaphology, pedology, history, etc., description of sampling methods, proper interviews conducted with the participants, scientific identification of the species involved and data analysis by statistical methods including comparison with previous data (Cunningham, 2001; de Albuquerque and Hurrell, 2010; de Medeiros et al., 2013; Akbulut and Bayramoglu, 2014; Albuquerque et al., 2014; Conde et al., 2014; Pieroni and Privitera, 2014; Akbulut, 2015; Taylor and Lovell, 2015) or with the help of bioinformatics (Torre et al., 2012; Quave et al., 2012; Lagunin et al., 2014) The questions addressed are as follows:

How TBK accounts for sustainability and selection?

What are the roles of a specific species or genus in a society or community?

Evaluation of this knowledge for satisfying community needs.

These studies prevailed across the globe. A brief account of the ethnobotanical literature has been given in the Supplementary Table 1, where the main families and species uses have been described.

Urban ethnopharmacology in north and south American countries

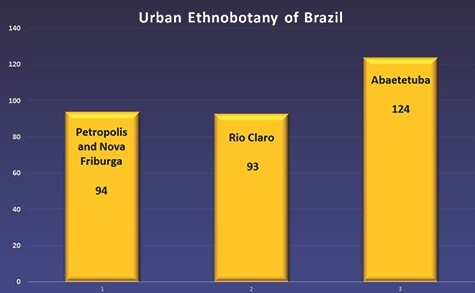

A large number of South American literatures, especially from Brazil, were found regarding the use of plants as alternative medicine in urban areas. Extensive studies have been done in a number of South American cities like Petrópolis, Nova Friburgo, Rio Claro, Abaetetuba, etc. (Hurrell et al., 2015). This shows the importance and preservation of traditional knowledge among the urban population. However, in spite of these practices, ethnobotanical knowledge was found to be inversely proportional to financial status and education in Brazil (Arenas et al., 2013) drawing attention to its conservation and widespread awareness. North America showed contrasting results. Limited jobs and lack of funding is a considerable limitation (Barkaoui et al., 2017), and hence TBK mainly was under practice in some parts of Mexico (Saynes-Vásquez et al., 2016; Lara Reimers et al., 2019). Occasionally, children from privileged families having private insurance in the USA were seen using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as a supplement to conventional medicine (Barnes et al., 2008).

In Brazil, De Melo et al. studied various medicinal plants having anticancer properties. A total number of 84 plants were listed, out of which Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. (Asphodelaceae), Euphorbia tirucalli L. (Euphorbiaceae) and Handroanthus impetiginosus (Mart. ex DC.) Mattos [= Tabebuia impetiginosa (Mart. ex DC.) Standl., Bignoniaceae] with the molecules of silibinin, β-lapachone, plumbagin and capsaicin were studied both in vivo and in vitro (De Melo et al., 2011). In the open fairs of Petrópolis and Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro, 94 species of medicinal plants were reported, with the families of Asteraceae (26 species) and Lamiaceae (10 species) being the most frequently represented. Common species included Ageratum conyzoides (L.) L. (Asteraceae), Dasyanthina serrata (Less.) H.Rob. (= Vernonia serrata Less., Asteraceae), Baccharis dracunculifolia DC. (Asteraceae), Mentha pulegium L. (Lamiaceae), Rosmarinus officinalis L. (Lamiaceae), etc. (Eichemberg et al., 2009). In a review article by Abreu et al., a total of 717 medicinal plant species were identified, out of which R. officinalis, Ruta graveolens L. (Rutaceae), Aloe arborescens Mill. (Asphodelaceae), Bidens pilosa L. (Asteraceae) and Plectranthus barbatus Andrews (Lamiaceae) were the most important documented plants in Brazilian ethnobotanical literature (Abreu et al., 2015; De Melo et al., 2011). The urban old gardens of Rio Claro house 93 species of medicinal plants with Rutaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Araceae, Asteraceae and Solanaceae as the most representative families. Notable species included Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Sch.Bip. [= Chrysanthemum parthenium (L.) Bernh., Asteraceae], Zinnia elegans L. (Asteraceae), Lactuca sativa L. (Asteraceae), Begonia bowerae Ziesenh. (= B. boveri Ziesenh., Begoniaceae) etc. (Eichemberg et al., 2009; Amorozo, 2002). In the home gardens of Abaetetuba, a city in Pará state, Brazil, 124 species were identified, 17.6% of which was used for curing infectious and parasitic diseases. Hemigraphis colorata W. Bull (Acanthaceae) was used to treat haemorrhoids and ear infections; Justicia pectoralis Jacq. (Acanthaceae) for uterine infections; Justicia secunda Vahl for gastric ailments; Sambucus nigra L. (Adoxaceae) for flu measles, chickenpox, wounds and cough; Alternanthera brasiliana (L.) Kuntze (Amaranthaceae) for urinary tract infections; Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants (Amaranthaceae) for asthma; Mangifera indica L. (Anacardiaceae) for diarrhea; Annona muricata L. (Annonaceae) for obesity and diabetes; and Eryngium foetidum L. (Apiaceae) for intestinal worms (Palheta et al., 2017; WinklerPrins and Oliveira, 2010). A total number of 129 medicinal plants were found to be used in La Paz and El Alto cities in Bolivia, including the following: Pimpinella anisum L. (Apiaceae) for the treatment of diarrhea and stomach ache; Baccharis genistelloides (Lam.) Pers. (Asteraceae) for diabetes; Mutisia acuminata Ruiz & Pav. (Asteraceae) for dizziness, headache and kidney ailments; and Xanthium spinosum L. (Asteraceae) for measles and chicken pox etc. (Macía et al., 2005).

Fifty species of edible and medicinal plants were found in a study conducted at markets of Bolivian immigrants in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Coriandrum sativum L. (Apiaceae), Baccharis articulata (Lam.) Pers. (Asteraceae), Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. (Cactaceae), Lepidium meyenii Walp. (Brassicaceae), etc., were some of the notable plants found (Arenas et al., 2013; Pochettino et al., 2012). A graphical representation of these information is presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Graphical ethnobotanical data from four Brazilian urban areas. Y-axis, number of medicinal plant species in urban home gardens.

In Mexico, herbal medicine is used by more than 90% of the population (Popoca et al., 1998). Fucus vesiculosus L. (Fucaceae), Citrus × aurantium L. (Rutaceae), Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck (Rutaceae), Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Malvaceae), etc., were used against obesity (Arenas et al., 2013). A total of 181 plant species having potent antitumor effects were identified (Alonso-Castro et al., 2011), including Justicia spicigera Schltdl. (Acanthaceae), Agave salmiana Otto ex Salm-Dyck (Asparagaceae) (Popoca et al., 1998), B. pilosa L. (Asteraceae) (Nieto et al., 2008), Dendropanax arboreus (L.) Decne. & Planch. (Araliaceae) (Hernández, 1959), Aristolochia brevipes Benth. (Aristolochiaceae), etc. Other medicinal plants are Agave vilmoriniana A. Berger (Asparagaceae), D. ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants (= Chenopodium ambrosiodes L., Amaranthaceae), Cosmos pringlei B.L. Rob. & Fernald (Asteraceae), Jatropha sp. (Euphorbiaceae), Zornia sp. (Fabaceae), etc. (Bye, 1986). However, with the advent of modernization and better quality of living, erosion of this knowledge is prevalent (Bensoussan et al., 1998).

Ethnopharmacology as a discipline is still under development in the USA due to limited job opportunities (Barkaoui et al., 2017). Brazilian Candomblé and Santería immigrants in New York use medicinal plants of Brazilian, Latino and West African origins like Allium cepa L. (Amaryllidaceae), A. vera (Asphodelaceae), Amaranthus hybridus L. (Amaranthaceae), Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. (Asteraceae), A. indica A. Juss. (Meliaceae), D. ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants (= Chenopodium ambrosiodes L., Amaranthaceae), Cocos nucifera L. (Arecaceae), Cinnamomum cassia (L.) J. Presl (= C. aromaticum Nees, Lauraceae), Dracaena fragrans (L.) Ker Gawl. (Asparagaceae), Mentha sp. (Lamiaceae), Mimosa pudica L. (Fabaceae), Nicotiana tabacum L. (Solanaceae), etc. (Fonseca and Balick, 2018). Latino healers use Achillea millefolium L. (Asteraceae), Daucus carota L. (Apiaceae), Eucalyptus sp. (Myrtaceae), R. officinalis L. (Lamiaceae), etc., for uterine fibrosis; Plantago major L. (Plantaginaceae), Ruta chalepensis L. (Rutaceae), P. anisum L. (Apiaceae), O. ficus-indica (L.) Mill. (Cactaceae) and Tilia mandshurica Rupr. & Maxim. (Malvaceae) for menorrhagia; and Citrus sp. (Rutaceae) and Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Zingiberaceae) for hot flushes (Augustino and Gillah, 2005). Chinese and Taiwanese immigrants in the metro-Atlanta area use A. cepa, A. sativum (both Amaryllidaceae), Cucurbita sp. (Cucurbitaceae), Ginkgo biloba L. (Ginkgoaceae), Bambusa oldhamii Munro (Poaceae), Lycium chinense Mill. (Solanaceae), Z. officinale (Zingiberaceae), etc., for the preparation of medicinal foods (Jiang and Quave, 2013). Knowledge about local plants was also found in the non-native students of Arizona (O’Brien, 2010). American Indians utilize Eupatorium perfoliatum L. (bonest, Asteraceae), Podophyllum peltatum L. (mayapple, Berberidaceae), Panax quinquefolius L. (ginseng, Araliaceae), etc., whereas in Honduras medicinal plants are widely used by Miskitos, Sumus, Pech and Lencas, Pipiles of El Salvador and Talamancas of Costa Rica (Hoareau and DaSilva, 1999).

In Canada, 400 species of medicinal plants are used by the native people living in Montreal, Quebec, and Ontario, including Populus balsamifera L. (Salicaceae), Thuja occidentalis L. (Cupressaceae), Geranium maculatum L. (Geraniaceae), etc. (Arnason et al., 1981), although TBK has suffered erosion in recent years (Turner and Turner, 2008).

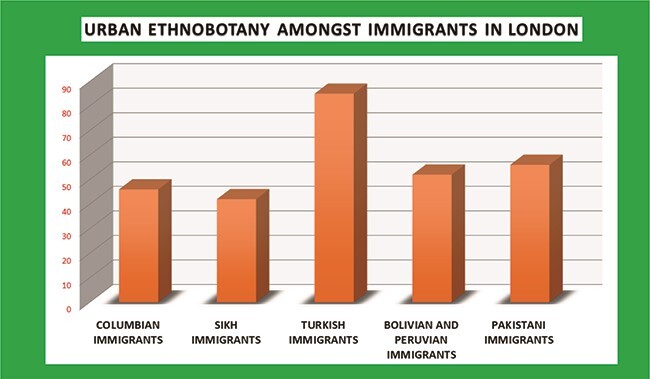

Urban ethnopharmacology in Europe

In Europe, increased dependence on natural remedies can be seen in recent years (Coady and Boylan, 2014; Pardo-de-Santayana et al., 2015; Petrakou et al., 2020). Use of natural products escalated after the Second World War, due to considerable financial and resource losses (Pardo-de-Santayana et al., 2015). Interestingly, a number of literatures are recorded from London, England, where five types of immigrants have a rich knowledge of herbal medicine (Fig. 3). This is way different from the information found from USA, another developed first world nation. The Thymus vulgaris L. (Lamiaceae), S. nigra L. (Adoxaceae), Santolina chamaecyparissus L. (Asteraceae), A. cepa, etc., were used in Spain; Geranium purpureum Vill. (Geraniaceae), Phlomis purpurea L. (Lamiaceae), M. pulegium L. (Lamiaceae), Juglans regia L. (Juglandaceae), etc, in Portugal; and Chelidonium majus L. (Papaveraceae), Crataegus monogyna Jacq. (Rosaceae), Chamaemelum nobile (L.) All. (Asteraceae), Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (Apiaceae), Malva sylvestris L. (Malvaceae), M. pulegium, Paronychia argentea Lam. (Caryophyllaceae), S. chamaecyparissus, R. officinalis and S. nigra were used in Greece and Turkey (Quave et al., 2012; Akaydin et al., 2013, Kilic and Bagci, 2013; Yesilada, 2013; Akbulut and Bayramoglu, 2014). Home remedies were used to treat common disorders such as catarrh, pneumonia, fever, diarrhoea, stomach and intestinal disorders, high blood pressure, wounds, bruises or muscular pain (Carvalho, 2010; Quave, and Pieroni, 2015). Colombian communities in London use 46 plant species as herbal medicine like M. indica (Anacardiaceae) and Anethum graveolens L. (Apiaceae) for stomach ailments, Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss (Apiaceae) for epilepsy, Erythroxylum coca Lam. (Erythroxylaceae) for dental problems, etc. (Ceuterick et al., 2008). Forty two species were found to be used by the Sikh groups in London with A. cepa, A. sativum, Capsicum annuum L. (= C. frutescens L., Solanaceae), Cinnamomum verum J. Presl (Lauraceae), C. limon, F. vulgare, Elettaria cardamomum (L.) Maton and Z. officinale Roscoe (both latter Zingiberaceae) serving as the most common species (Sandhu and Heinrich, 2005). Turkish speaking Cypriots treat 13 ailments with the help of 85 different plants like Olea europaea L. (Oleaceae), C. limon, Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. (Myrtaceae), S. nigra, Urtica urens L. (Urticaceae), A. cepa, A. sativum, C. verum J.Presl (= C. zeylanicum Blume, Lauraceae), M. sylvestris L./parviflora L. (Malvaceae), Origanum syriacum L. (Lamiaceae), Saxifraga hederacea L. (Saxifragaceae) and Tilia cordata Mill. (Malvaceae) (Yöney et al., 2010). Bolivian and Peruvian migrants use Matricaria chamomilla L. (= M. recutita L., Asteraceae), Carica papaya L. (Caricaceae), Gnaphalium versatile Rusby (Asteraceae), Eucalyptus globulus Labill. (Myrtaceae), P. major, Chenopodium quinoa Willd. (Amaranthaceae), Morinda citrifolia L. (Rubiaceae), etc. (Ceuterick et al., 2011). Pakistani migrants use 56 plant-based Unani medicines for different ailments in Bradford (Pieroni et al., 2008). Senegalese community living in Turin, Italy, uses Acacia nilotica (L.) Delile (Fabaceae) for toothache, Adansonia digitata L. (Malvaceae) for diarrhoea, C. limon for malaria, Euphorbia balsamifera Aiton (Euphorbiaceae) for wounds and Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M.Perry (= Eugenia caryophyllata Thunb., Myrtaceae) for eye problems (Fassina et al., 2002). Venetian migrants from Romania have 135 plant-based food and medicinal preparations including the species of A. millefolium, Amaranthus retroflexus L. (Amaranthaceae), Artemisia abrotanum L. (Asteraceae), Calendula officinalis L. (Asteraceae), Iris × germanica L. (Iridaceae), N. tabacum, Ocimum basilicum L. (Lamiaceae), etc. (Borza, 1968; Pieroni et al., 2012). C. officinalis, Valeriana officinalis L. (Caprifoliaceae), Hypericum perforatum L. (Hypericaceae), Artemisia absinthium L. (Asteraceae), A. millefolium, Acorus calamus L. (Acoraceae) and Aesculus hippocastanum L. (Sapindaceae) are the most widely used plants in urban Samogitia region, Lithuania (Petkeviciute et al., 2010). In French Guiana, 226 medicinal and cosmetic plants are used by the urban youth, including Aristolochia trilobata L. (Aristolochiaceae), Carapa guianensis Aubl. (Meliaceae), Cannabis sativa L. (Cannabaceae), Orthosiphon aristatus (Blume) Miq. (Lamiaceae), etc. (Tareau et al., 2017). Urban populations in Paramaribo, Suriname utilize 144 medicinal plants with Gossypium barbadense L. (Malvaceae), Phyllanthus amarus Schumach. & Thonn. (Phyllanthaceae) and Quassia amara L. (Simaroubaceae) being the most frequently mentioned species (van Andel and Carvalheiro, 2013).

Figure 3.

Graph of ethnobotanical data of London. Y-axis, number of medicinal plant species used by different groups of immigrants.

Urban ethnopharmacology in Africa

Africa is a continent with a rich biodiversity and miscellaneous ethnic groups. Each ethnic group has their own knowledge and medicinal practices. As the regions developed and the urban and rural divisions became blurred, these traditions seeped into the urban populations (Oreagba et al., 2011). Several of these practices are now prevalent in cities (Amira and Okubadejo, 2007; Hughes et al., 2015). Bush doctors of Western Cape in South Africa treat more than 30 illnesses including 12 gastrointestinal symptoms, urogenital infections, skin problems and cardiovascular diseases with the help of 181 plant species like Acacia dealbata Link (Fabaceae), Agathosma crenulata (L.) Pillans (Rutaceae), Aloe ferox Mill. (Asphodelaceae), Asparagus sp. (Asparagaceae), Crossyne guttata (L.) D. Müll.-Doblies & U.Müll.-Doblies (Amaryllidaceae), Dioscorea sylvatica Eckl. (Dioscoreaceae), Gnidia capitata L.f. (Thymelaeaceae), Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (Lamiaceae), Pelargonium triste (L.) L’Hér. (Geraniaceae), R. graveolens, Salvia africana-lutea L. (Lamiaceae), Zanthoxylum capense (Thunb.) Harv. (Rutaceae), etc. (Philander, 2011; Maroyi and Mosina, 2014). In Kenya, 13 plant species—Aloe deserti A. Berger (Asphodelaceae), Launaea cornuta (Hochst. ex Oliv. & Hiern) C. Jeffrey (Asteraceae), O. basilicum L. (Lamiaceae), Vepris simplicifolia (Engl.) Mziray [= Teclea simplicifolia (Engl.) I. Verd., Rutaceae], Gerrardanthus lobatus (Cogn.) C. Jeffrey (Cucurbitaceae), Grewia hexamita Burret (Malvaceae), Canthium glaucum Hiern (Rubiaceae), A. hybridus L. (Amaranthaceae), Combretum padoides Engl. & Diels (Combretaceae), Senecio pinifolius Dusén (Asteraceae), Ocimum gratissimum L. (= O. suave Willd., Lamiaceae), Aloe macrosiphon Baker (Asphodelaceae) and Landolphia buchananii (Hallier f.) Stapf (Apocynaceae)—are used in the treatment of malaria (Njoroge and Kibunga, 2007, Nguta et al., 2010). In urban districts of Tanzania, some of the notable herbal medicines used (Mhame, 2000) are as follows: Abrus precatorius L. (Fabaceae) for treating viral and bacterial infections, stomach ache, eye ache, haemorrhoids; Acacia polyacantha Willd. (Fabaceae) for labour pain and infertility; A. digitata L. (Malvaceae) for tuberculosis; Albizia harveyi E. Fourn. (Fabaceae) for snake bites; and Catharanthus roseus (L.) G.Don (Apocynaceae) for hypertension and diabetes mellitus. In Moroccan urban areas, cutaneous infections were treated by A. cepa L., Lawsonia inermis L. (Lythraceae), Lepidium sativum L. (Brassicaceae), Artemisia herba-alba Asso (Asteraceae), Carlina gummifera (L.) Less. (= Atractylis gummifera Salzm. ex L., Asteraceae), C. limon (L.) Osbeck (Rutaceae), Marrubium vulgare L., Salvia verbenaca L. (both latter Lamiaceae), Quercus infectoria G. Olivier (Fagaceae), Solanum lycopersicum L. (Solanaceae), R. officinalis L. (= Salvia rosmarinus Schleid., Lamiaceae), A. sativum L. (Amaryllidaceae), Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels (Sapotaceae), Carpobrotus edulis (L.) N.E.Br. (Aizoaceae), O. europaea L. (Oleaceae), Ziziphus jujuba Mill. (= Z. vulgaris Lam., Rhamnaceae), Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast. (Cupressaceae) and Juniperus oxycedrus L. (Cupressaceae), whereas A. sativum, Salvia officinalis L., Marrubium vulgare L. and Lavandula dentata L. (last three belong to Lamiaceae) were used as anti-diabetic agents (Ouhaddou et al., 2014; Makbli et al., 2016; Barkaoui et al., 2017).

Urban ethnopharmacology in Asia

Asia is well known for its rich cultural heritage and biodiversity. As a result, a large number of publications were recorded on the modern-day usage of botanical products in urban regions. The literature was mainly from Southern Asia, having both developed and developing nations (Astutik et al., 2019). China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Indonesia had the most publications. Use of plants has been prevalent in Chinese traditional medicine (Tu, 2011; Tang and Eisenbrand, 2013). Ephedra sinica Stapf (Ephedraceae) was found to be effective against constipation, Artemisia annua L. (Asteraceae) could kill Quinine resistant Plasmodium sp. and Coix lacryma-jobi L. (Poaceae) had potent anti-tumour effects (Normile, 2003). A total of 20 traditional Chinese medicine was useful against irritable bowel syndrome in Sydney, Australia. The species included Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf (Campanulaceae), Z. officinale Roscoe (Zingiberaceae), etc. (Bensoussan, 1998). Traditional Indian medicine or Ayurveda has similarities with traditional Chinese medicine (Yuan et al., 2016). Species commonly used in Ayurveda are as follows: Sesbania grandiflora (L.) Pers. (Fabaceae), Phyllanthus emblica L. (Phyllanthaceae), Terminalia arjuna (Roxb. ex DC.) Wight & Arn. (Combretaceae), Saraca asoca (Roxb.) Willd. (Fabaceae), Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Solanaceae), Ficus religiosa L. (Moraceae), Santalum album L. (Santalaceae), Terminalia chebula Retz. (Combretaceae), Piper betle L. (Piperaceae), etc. (Sharma et al., 2005, Parasuraman et al., 2014). Commiphora sp. (Burseraceae) for controlling cholesterol, Picrorhiza sp. (Plantaginaceae) for liver problems, Bacopa sp. (Plantaginaceae) for improving memory, Curcuma sp. (Zingiberaceae) as an anti-allergic medicine and Asclepias sp. (Apocynaceae) against cardiac disorders are some of the recent developments in the commercial use of ancient herbal knowledge (Shrikumar and Ravi, 2007; Patwardhan and Mashelkar, 2009; Anand et al., 2020; Banerjee et al., 2021; Halder et al., 2021). Dysentery was treated with Andrographolide from Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) Nees (Acanthaceae). Morphine was isolated from Papaver somniferum L. (Papaveraceae). Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. (Fabaceae) served as a source of L-Dopa (Tandon et al., 2021), a substitute for Dopamine and Taxus brevifolia Nutt. (Taxaceae) gave paclitaxel, an antineoplastic drug (Jarukamjorn and Nemoto, 2008; Katiyar et al., 2012; Das et al., 2021). Theasinensin D from Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze (= Thea sinensis L., Theaceae) can be used against human immunodeficiency virus (Hashimoto et al., 1996; Fassina et al., 2002; Nance and Shearer, 2003: Liu et al., 2005; Bhutani and Gohil, 2010) and Selaginella bryopteris (L.) Baker (Selaginellaceae) is effective to kill Plasmodium falciparum (Kunert et al., 2008; Bhutani and Gohil, 2010; Cao et al., 2010; Pandey et al., 2017;). Unani medicine is a popular choice among the urban population of Pakistan (Shaikh and Hatcher, 2005; Shaikh et al., 2009). Twenty-nine medicinal plants like Achyranthes aspera L. (Amaranthaceae) for kidney stones, Adiantum incisum Forssk. (Pteridaceae) for bronchitis, Aerva javanica (Burm.f.) Juss. ex Schult. (Amaranthaceae) for flatulence and Senna occidentalis (L.) Link (= Cassia occidentalis L.) for snake bites, etc., are used in the urban population of Mirpur district (Mahmood et al., 2011). Mianwali district inhabitants used 26 medicinal plants including F. religiosa L. (Moraceae) for menstrual disorders, Morus alba L. (Moraceae) for diabetes and hypertension, Fagonia arabica L. (Zygophyllaceae) for diabetes and Morus nigra L. (Moraceae) as a laxative (Qureshi et al., 2007). In Abbottabad, 47 plant species like Colchicum luteum Baker (Colchicaceae), Lactuca serriola L. (Asteraceae) and Cyperus rotundus L. (Cyperaceae) are used for treating different ailments (Qureshi et al., 2007). In Mastung district of Balochistan, 102 plants are used as herbal treatments out of which Caralluma tuberculata N.E.Br. (Apocynaceae), Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. (Cucurbitaceae) and Mentha longifolia (L.) L. (Lamiaceae) were the most common species (Bibi et al., 2014). Traditional Jamu medicine is widely used in Yogyakarta, Indonesia (Torri, 2013). In Dhaka, Bangladesh, 37 anti-diabetic plants are used such as Coccinia grandis (L.) Voigt (= Coccinia indica Wight & Arn., Cucurbitaceae), A. indica A. Juss. (Meliaceae), T. chebula Retz. (Combretaceae), Ficus racemosa L. (Moraceae), Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae) and Swietenia mahagoni (L.) Jacq. (Meliaceae) (Ocvirk et al., 2013). Usage of traditional Chinese medicine was seen in children in Singapore, again showing the cross-cultural manifestation of urban ethnobotanical knowledge (Loh, 2009).

Urban ethnopharmacology in Australia

Australian urban people prefer using alternative herbal medicine along with conventional treatments for faster healing (Fisher et al., 2018). Around 48% of the overall population in Australia uses alternative medicine, a vast number of whom were urban and mostly educated women (MacLennan et al., 1996). CAM practisers are consulted by 28% urban women (Adams et al., 2011). In a study in 2002, it was found that 32% insured urban adults treat neuromuscular diseases with alternative medicine in Washington State (Lind et al., 2009). Some of these herbal medicines, like Ginseng, were self-prescribed (Steel et al., 2018). Prevalence of use of Chinese medicine again shows the cross-cultural nature of TBK (Sibbritt et al., 2013). According to a population survey conducted in the year 2007, in Victoria, 90% of the population believe medicinal plant usage is beneficial and 22.6% had used some herbs in their lifetime (Zhang et al., 2008). Tea [C. sinensis (L.) Kuntze (= Thea sinensis L., Theaceae)], A. vera and garlic were the most popular. Ginseng, Peppermint, Chamomile, Ginkgo, Senna, Valerian, Dandelion, Liquorice and St John’s Wart were some of the other herbs identified (Zhang et al., 2008). However, as herbal treatment is becoming increasingly popular among the urban people and is falling under health insurance policies, the cost of treatment is escalating. Hence, soon like in the USA, herbal medicine might be a luxury of the rich and privileged even in Australia.

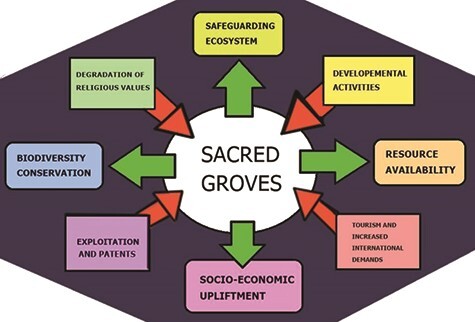

Yum Kaax: role of plants in religion

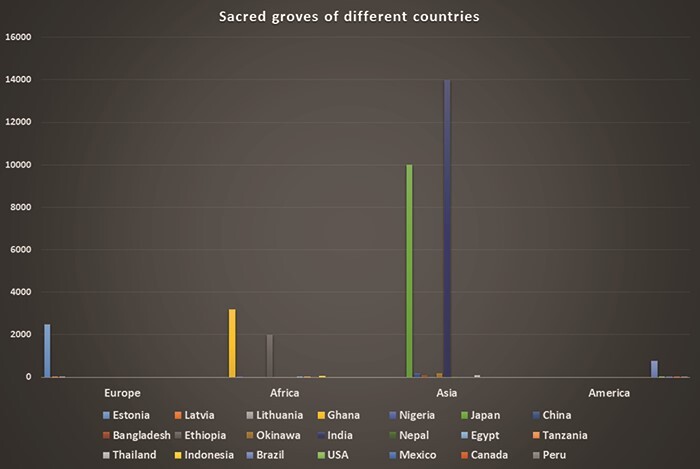

Since ages, plants and their products have been used as offerings in religious ceremonies (Kessler et al., 2013; Frazão-Moreira, 2016; Quiroz and van Andel, 2018) or have been worshipped as sacred deities, which play an important role in their conservation. Majority of these plants had medicinal values. The God-fearing nature of human beings obliged them to protect both domestic and wild varieties and hence these practices acted like gene banks (Child, 1993). From Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden resulting from an apple to the tree of Bodhi, different plant species are deep rooted in almost every religion and mythology persisting on Earth. Human beings, who otherwise are selfish and have no empathy for nature, shift to sustainable use or cultivation of these special botanicals since they have to continue these rituals for ages. In some cases, religious leaders also play a substantial role in shaping the mind of a population towards conservation needs. Harming or cutting such trees is considered to be a sin and hence it is an effective tool to involve locals in safe guarding nature. These groups not only restrict their own consumption of the plants but also prevent overuse or theft by outsiders. Sacred groves are thickets or woodlands bearing plants of religious significance to certain communities or might be locations of important historical or mythological events (Adeniyi et al., 2018; Mequanint et al., 2020). The significance and the factors responsible for degradation of sacred groves have been depicted in Fig. 4. There are more than 100 000 sacred groves around the world, mainly concentrated in India, Nepal, South America, Japan and parts of Africa, some of which serving even as micro biosphere reserves. A graphical representation of sacred groves of the world and a map of country-wise occurrence major sacred groves are presented in Figs 5 and 6, respectively. The paganism and polytheistic religions teach nature worship and hence are mainly involved in the maintenance of these groves. As education and financial stability lead to the development and thus degradation of religious and cultural values, people tend to forget the important and sacredness of these groves leading to their exploitation and negligence of conservation.

Figure 4.

Role of sacred groves (green arrows) and factors responsible their degradation (red arrows).

Figure 5.

Sacred groves of different countries. Y-axis, number of sacred groves by country.

Figure 6.

Map of sacred groves in the world.

Plants in Christianity and Islam

For Monotheistic religions, i.e. the Abrahamic religions ‘Nature’ and hence trees ‘continue to be a source of Evil’. Satan came in the form of a snake enticing Eve to take a bite from the apple [Malus domestica Borkh. (Rosaceae)] of the tree of wisdom, which ultimately led to the Original Sin. In Genesis 1.29, it is written that God has instructed man, ‘See, I give you every seed-bearing plant that is upon all the earth, and every tree that has seed-bearing fruit; they shall be yours for food.’ The Bible has references to more than 36 trees (Coder, 2011; Evans, 2014) and is itself known as ‘The Tree of Life’ according to Proverbs3:18 Joyce Kilmer expressed ‘I think that I shall never see, a poem as lovely as a tree’, while studying Biblical verses mentioning trees. Old Testament predicted that Jesus’s death will occur on a tree and it was fulfilled, since the cross was made up of dogwood [Cornus sp., Cornaceae]. In John15:1, Jesus referred to himself as the ‘True Vine’ and his father as ‘The Gardener’. Trees are associated with a number of characters in Bible, such as Noah and the olive branch [O. europaea L. (Oleaceae)], Abraham rested under ‘the Oaks of Mamre’ [Quercus sp, Fagaceae], Zacchaeus ascended ‘The sycamore fig’ [Ficus carica L., Moraceae], Jacob and Almond trees [Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A. Webb, Rosaceae], Elijah and Juniper tree [Juniperus sp., Cupressaceae] and David with Balsam trees [Abies balsamea (L.) Mill., Pinaceae]. In Exodus, Deuteronomy and Kings, Bible associated paganism with sacred groves and ordered Jews to burn pagan groves. Supplementary Table 2 lists the trees mentioned in Biblical tales and verses.

Islam, similar to Christianity, is another religion that believes in a single God and considers Nature to be opposite to God. There were many incidences in history where sacred groves were not protected by the Muslims (Campbell, 2005; Dafni, 2006). Many scholars also preached that trees can never be sacred (Dafni, 2011). In spite of all these prejudices, a number of trees have been mentioned in the Holy texts (Table 1), particularly the Sidra al-Munahā or the sacred lote tree denoting the edge of the 7th heaven, cypress, olive, date and fig trees. Graveyards have a lot of trees and these grounds are considered as holy and entry might be restricted (Dafni, 2006).

Table 1.

List of plants mentioned in Islamic religious texts

| Common names | Scientific names | References |

|---|---|---|

| Apple | M. domestica Borkh. | Quran 2:7–286 |

| Corn | Zea mays L. | Quran 55:5–72 |

| Cucumber | Cucumis sativus L. | Quran 2:61 |

| Date Palm | Phoenix dactylifera L. | Quran55:5–72 |

| Fig | F. carica L. | Quran 95:1–8 |

| Garlic | A. sativum L. | Quran 2:61 |

| Gourd | Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. | al-Saaffaat 37:139, 142–146 |

| Grape | Vitis vinifera L. | Quran 17:91 |

| Honeyberry | Celtis australis L. | Quran 34:10–18 |

| Lentil | Lens culinaris Medik. (= Lens esculenta Moench) | Quran 2:61 |

| Olive | O. europaea L. | Quran 95:1–8 |

| Onion | A. cepa L. | Quran 2:61 |

| Palm tree | Arecaceae Bercht. & J. Presl | Quran 59:3 |

| Pomegranate | Punica granatum L. | Quran 55:5–72 |

| Tamarisk | Tamarix aphylla (L.) H.Karst. | Quran 34:10–18 |

| Wheat | Triticum sp. | Quran 2:61 |

Plants in Hinduism and Buddhism

Polytheistic religions value nature, hence Hinduism gives importance to considering trees as sacred beings. Nature worship is practiced as several trees are seen as Gods like Peepal, Banyan, banana, Ashoka and Neem. Majority of these plants have medicinal properties. Trees are worshipped as their products, help in healing and provide food and nourishment. A list of some of the species are described in Table 2. Trees like Tulsi are sometimes found in the majority of Hindu households since keeping them are as compulsory as keeping shrines. Several natural products are used in ritualistic practices or as offerings to deities. Apart from nature worship, several forests and groves are directly associated with mythological stories and hence entry is restricted and commercial overexploitation is forbidden. Hinduism also considers all beings as sentient and connected directly to Brahma, the creator (Framarin, 2014). They are also part of the ‘Cycle of Death and Rebirth’ (Hall, 2011) and are able to experience ‘pain and happiness’ (Dwivedi, 1990) and hence hurting them is considered to be unholy. There are also festivals where tree planting is a ritual and the trees are planted according to astrology (Coward, 2003; Haberman, 2013). Planting trees and conservation of groves are considered of high religious merit since groves and forests serve as religious prayer sites (Nath and Mukherjee, 2015; Sarma and Devi, 2015).

Table 2.

List of plants of religious and medicinal significance in Hinduism

| Common names | Scientific names | Local names |

|---|---|---|

| Wood Apple | Aegle marmelos (L.) Corrêa | Bel |

| Indian Wormwood | Artemisia nilagirica (C.B. Clarke) Pamp. | Kunju |

| Jackfruit | Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. | Kathal |

| Indian Lilac | A. indica A. Juss. | Neem |

| Himalayan Birch | Betula utilis D. Don | Bhojpatra |

| Ngai Camphor | Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC. | Bari ilaichi |

| Rubber Bush | Calotropis procera (Aiton) Dryand. | Aak |

| Himalayan Cedar | Cedrus deodara (Roxb. ex D. Don) G. Don | Deodar |

| Camphor | Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl | Kapur |

| Bermuda grass | Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | Dhoob |

| Jimson weed | Datura stramonium L. | Dhutra |

| Halfa grass | Desmostachya bipinnata (L.) Stapf | Kush |

| Woodenbegar | Elaeocarpus serratus L. (= Elaeocarpus ganitrus Roxb. ex G. Don) | Rudraksh |

| Indian Gooseberry | P. emblica L. (= Emblica officinalis Gaertn.) | Amla |

| Indian Coral Tree | Erythrina variegata L. (= Erythrina indica Lam.) | Paribhadraka |

| Banyan fig | Ficus benghalensis L. | Bargad |

| Sacred fig | F. religiosa L. | Pipal |

| Mango | Mangifera indica L. | Aam |

| Banana | Musa × paradisiaca L. | Kela |

| Basil | Ocimum tenuiflorum L. (= Ocimum sanctum L.) | Tulsi |

| Asian rice | Oryza sativa L. | Chawal |

| Long Leaf Indian Pine | Pinus roxburghii Sarg. | Chir |

| Betel Vine | P. betle L. | Paan |

| Himalayan Cherry | Prinsepia utilis Royle | Bhakel |

| Spunge Tree | Prosopis cineraria (L.) Druce | Khejri |

| Bird Cherry | Prunus cerasoides Buch.-Ham. ex D. Don | Paiya |

| Pomegranate | P. granatum L. | Anar |

| Woolly Oak | Quercus oblongata D.Don (= Quercus leucotrichophora A. Camus) | Banjh |

| Sandal | S. album L. | Chandan |

| Queen of the Night | Saussurea obvallata (DC.) Edgew. | Brahmakamal |

| White Marudah | T. arjuna (Roxb. ex DC.) Wight & Arn. | Arjun |

| Indian Mahogany | Toona ciliata M. Roem. | Tun |

| Indonesian lemon pepper | Zanthoxylum acanthopodium DC. | Timoor |

| Winged Prickly Ash | Zanthoxylum armatum DC. | Tejphal |

Buddhism is neither monotheistic nor polytheistic, rather than giving all control and power to single or multiple gods, it gives importance to humanity, self-control and spirituality. Harming any living being including plants is considered sinful. Several plants are associated with the life of Buddha and are considered to be holy (Table 3), partly because Buddhism emerged from Hinduism and some of the principles have been retained (Hrynkow, 2017) and obtaining the rest of it from animism beliefs of Shinto religion (Omura, 2004). Ashoka tree is associated with Buddha’s birth and Peepal tree is the Bodhi tree. Furthermore, natural products are used as offerings and in other rituals by monks including some timber producing trees (Sahni, 2007; Upadhyay and Prasad, 2011).

Table 3.

Plants of religious importance in Buddhism

| Sl. No. | Common names | Scientific names |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acacia | Acacia rugata (Lam.) Fawc. & Rendle |

| 2 | Anatto tree | Bixa orellana L. |

| 3 | Ashoka Tree | Saraca indica L. |

| 4 | Ba jiao | Musa × paradisiaca L. (= M. sapientum L.) |

| 5 | Banana | Musa nana Lour. |

| 6 | Basil/ Tulasi | O. basilicum L. |

| 7 | Betel Leaf/ Paan | P. betle L. (= P. betel Blanco) |

| 8 | Bodhi Tree or Banyan | F. religiosa L. |

| 9 | Candle Nut tree | Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Willd. |

| 10 | Cannabis | C. sativa L. |

| 11 | China aster | Chrysanthemum indicum L. |

| 12 | Chittagong Wood | Chukrasia tabularis A. Juss. |

| 13 | Cinnamon | Cinnamomum sp. |

| 14 | Datura | Datura stramonium L. |

| 15 | English Beechwood/ Gamhar | Gmelina arborea Roxb. |

| 16 | Gardenia | Gardenia sootepensis Hutch. |

| 17 | Indian Gooseberry | P. emblica L. |

| 18 | Indian Mulberry | Morinda officinalis F.C. How |

| 19 | Ironwood | Mesua ferrea L. |

| 20 | Jackfruit | A. heterophyllus Lam. |

| 21 | Jasmine | Jasminum sp. |

| 22 | Juniper | Juniperus sp. |

| 23 | Lily | Hedychium coronarium J.Koenig (= H. chrysoleucum Hook.) |

| 24 | Lotus | Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. |

| 25 | Magnolia/Champa | Magnolia champaca (L.) Baill. ex Pierre |

| 26 | Malay bushbeech | G. arborea Roxb. |

| 27 | Mango | M. indica L. |

| 28 | Margosa | A. indica A.Juss. |

| 29 | Oak Apple tree/ Bilva Tree | A. marmelos (L.) Corrêa |

| 30 | Paper Mulberry | Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) L’Hér. ex Vent. |

| 31 | Pine | Pinus sp. |

| 32 | Rhododendron | Rhododendron sp. |

| 33 | Rose Apple | Syzygium sp. |

| 34 | Saal tree | Shorea robusta Gaertn. |

| 35 | St. John’s Lily | Crinum asiaticum L. |

| 36 | Sweet potato | Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. |

| 37 | Tamarisk | Tamarix sp. |

| 38 | Teak | Tectona grandis L.f. |

| 39 | Water Lily | Nymphaea sp. |

| 40 | Wild Plum | Z. jujuba Mill. |

Discussion

While urban people have widely embraced TBK, there are still a number of stones in the direction of its advancement. Lack of scientific evidence validating the functionality and working principles of several of the organisms involved seems to be another drawback, since individuals struggle to believe in its fruitfulness. These prescriptions operate slower than conventional treatment and require cumbersome preparations, so customers opt for commercial pharmaceuticals that offer immediate or swift relief and are considerably simpler to use. Most individuals prefer to obtain their medicines at their doorsteps instead of wasting hours, pounding blends or extracting fluids from foliage, roots, etc. By educating the public, defining statistics and clarifying viewers’ notions, the media plays a vital role; but at the same time this could be exploited to propagate fake stories or generate fear among the public.

The terms Ayurveda and herbal are so common that simply claiming a product as herbal or adding these terms as a prefix improves the appeal of the product and increases its market demand. Many people miss the goods’ ingredient labels and businesses benefit from this. Therefore, the knowledge established by rural elders and sustained for generations have thus intensified capitalism. The privileged became wealthier and the scions of the original discoverers continued life in cages of deprivation (Verma, 2002). A plethora of biopiracy cases have occurred (De Werra, 2009; Dunagan, 2009; Efferth et al., 2016; Ageh and Lall, 2019) where patents had been secured but the aboriginal populations concerned were not provided reasonable remunerations (Shiva, 2007; Shiva, 2016). Numerous American companies had copyrighted A. indica A. Juss. (Meliaceae) (Sheridan, 2005; Hamilton, 2006; Porter, 2006) and Curcuma longa L. (Zingiberaceae) (Udgaonkar, 2002; Schuler, 2004), two species that were used in India since ages. In Texas, where the company RiceTec declared Indian Basmati rice as ‘American-type Basmati’ and advertised it as its own invention, which was an example of both consumer misleading and biopiracy (Runguphan, 2004). This makes the potential use of these plant products illegal by members of the ethnic groups in that area, a phenomenon that directly challenges their livelihoods, totally beyond ethics and humanity. Scientists who patent these formulations justify their conduct by citing stronger benefits for the improvement of research and industrial applications such as drug discovery.

Nearly $5.4 trillion in royalties are tricked off every year from ethnic groups and tribes. Careful recording and maintenance by groups of these data or records could assist in preventing biopiracy, as in the case of turmeric in India. However, the best solution to this problem might be access to resources and advantage sharing. In short, it is the distribution of profits. Native tribes can patent their existing compositions and can then partner with corporations that, with the aid of branding and ambassadors, are involved in the production of raw materials and distribution of finished goods, but have to give a decent percentage of the revenue to the original inventors. In urban ethnopharmacology, IPR works as it gives exclusive rights, but the concept is reliant on collaborating. Bio-cultural legacy sees biodiversity and community as one and positions them in the category of collective rather than private ownership (Swiderska, 2006). The ethnic groups aid in the management and protection of natural resources with this approach. They are also able to avoid hunting, stealing and harm of resources by outsiders by making them guardians of the woods. However, they overexploit these tools as corporations get involved, contributing to their endangerment and rendering the ecological system vulnerable. This approach thus gives priority to preserving the whole and maintaining the balance of nature rather than individual plants.

Humans constitute an essential part of the planet. In the massive system called nature, all of us have respective roles. It is therefore our responsibility, as the most intelligent organisms, to manage and use these plant resources in sustainable ways for socioeconomic, cultural and economic growth. Thus, the line ‘country roads take me home’ may not necessarily be true since they often lead you towards new experiences and insights. Without human relationships, urban ethnopharmacology is nothing and thus if advanced nations persist with capitalizing developing countries, this might result in the disappearance of ancient medicinal and pastoral expertise. We should still realize that modernization needs the help of nature to suffice, but the reverse is contradictory.

Conclusions

Medicinal plant usage by urban people was seen in all continents; however, the trends have been different. In the Americas, herbal medicines were either a part of healthcare of the poor in the developing countries or are been used as a health supplement by the rich in the developed countries, where the costs of these products are very high. Generally, in countries like Brazil, TBK was inversely proportional to education and financial status. In USA, alternative medicine could only be afforded by the rich and there was a general negative attitude towards the effectiveness of traditional plant medicines among the urban people. In Europe, small ethnic groups or immigrant groups living in metropolitan cities like London have kept the rich knowledge of botanical medicine alive. Urban people of South and East Asian countries like China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Korea, Japan, Indonesia, etc., are highly dependent on herbal medicines belonging to all sections of the society, whereas negligible literature was found about usage in North and Western Asia. Herbal medicine industries in these countries generate substantial revenue. The trend in Africa is the same as southern Asia. Australian urban well-educated and employed women depend on alternative and herbal medicines, some of which are self-prescribed. However, as these treatments are being insured and becoming popular, the cost of treatment is increasing. Hence, soon like in the USA, herbal medicine might be a luxury of the rich and privileged even in Australia. In areas where tradition, culture and religion are an important part of the society, sacred groves and plants were prevalent, and some of them were of medicinal importance, since healing agents for diseases are considered holy. This plays a dominant role in their conservation. Monotheism normally shows plants in a negative light but does play some role in conservation by designating some groves as sacred or of ritualistic importance. Polytheism is inspired by animism and hence nature worship is frequently practiced. As a result, sacred groves are frequent in countries practicing polytheistic religions. However, there are still ways to go to recognize the contribution of the ethnic people with proper practices of bio-prospecting, avoiding biopiracy and protecting the consumer from misleading. Government, Non-Governmental Organizations and corporate sectors must carefully acknowledge the traditional wealth and the people and share a decent percentage of the revenue generated from commercial and sustainable utilization of ethnomedicinal knowledge.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Conservation Physiology online.

Author contributions

J.P. and A.D. conceptualized the theme and idea. T.D., U.A., S.C.S. and A.B.M. retrieved the literature and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T.D. and U.A. designed the figures and tables. T.D., U.A. and D.A.P. arranged the references. U.A., D.A.P., R.K. and J.P. proofread and revised the manuscript. R.K., J.P. and A.D. critically read and made the final editing of the manuscript. S.C.S., J.P. and A.D. supervised. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed before submission.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that this study (review) was conducted in the absence of any financial or commercial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abreu DBO, Santoro FR, Albuquerque UP, Ladio AH, Medeiros PM (2015) Medicinal plant knowledge in a context of cultural pluralism: a case study in Northeastern Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol 175: 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J, Sibbritt D, Lui CW (2011) The urban-rural divide in complementary and alternative medicine use: a longitudinal study of 10,638 women. BMC Complement Alt Med 11: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeniyi A, Asase A, Ekpe PK, Asitoakor BK, Adu-Gyamfi A, Avekor PY (2018) Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants from Ghana; confirmation of ethnobotanical uses, and review of biological and toxicological studies on medicinal plants used in Apra Hills Sacred Grove. J Herb Med 14: 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ageh PA, Lall N (2019) Biopiracy of plant resources and sustainable traditional knowledge system in Africa. Glob J Comp Law 8: 162–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad H, Khan SM, Ghafoor S, Ali N (2009) Ethnobotanical study of upper Siran. Int J Geogr Inf Syst 15: 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi TO, Moody JO (2016) Ethnobotanical survey of plants used in the management of obesity in Ibadan, South-Western Nigeria. Niger J Pharm Res 11: 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Akaydin G, Şimşek I, Arituluk ZC, Yeşilada E (2013) An ethnobotanical survey in selected towns of the Mediterranean subregion (Turkey). Turk J Bio 37: 230–247. [Google Scholar]

- Akbulut S (2015) Differences in the traditional use of wild plants between rural and urban areas: the sample of Adana. Stud EthnoMed 9: 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Akbulut S, Bayramoglu MM (2014) Reflections of socio-economic and demographic structure of urban and rural on the use of medicinal and aromatic plants: the sample of Trabzon Province. Studies on Ethno-Medicine 8: 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque UP, da Cunha LV, De Lucena RF, Alves RR (2014) Methods and Techniques in Ethnobiology and Ethnoecology. Springer,New York. [Google Scholar]

- Almada ED (2010) Sociobiodiversidade Urbana: por uma etnoecologia das cidades. In AL Valdeline Atanazio da Silva, Etnobiologia e Etnoecologia: Pessoas & Natureza na América Latina, 37–64.

- Alonso-Castro AJ, Villarreal ML, Salazar-Olivo LA, Gomez-Sanchez M, Dominguez F, Garcia-Carranca A (2011) Mexican medicinal plants used for cancer treatment: pharmacological, phytochemical and ethnobotanical studies. J Ethnopharmacol 133: 945–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alqethami A, Hawkins JA, Teixidor-Toneu I (2017) Medicinal plants used by women in Mecca: urban, Muslim and gendered knowledge.J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 13: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amagase H, Petesch BL, Matsuura H, Kasuga S, Itakura Y (2001) Intake of garlic and its bioactive components. J Nutr 131: 955S–962S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amira OC, Okubadejo NU (2007) Frequency of complementary and alternative medicine utilization in hypertensive patients attending an urban tertiary care centre in Nigeria. BMC Complement Alt Med 7: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorozo MCDM (2002) Uso e diversidade de plantas medicinais em Santo Antônio do Leverger, MT, Brasil. Acta Bot Bras 16: 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Anand U, Jacobo-Herrera N, Altemimi A, Lakhssassi N (2019) A comprehensive review on medicinal plants as antimicrobial therapeutics: potential avenues of biocompatible drug discovery. Metabolites 9: 258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand U, Nandy S, Mundhra A, Das N, Pandey DK, Dey A (2020) A review on antimicrobial botanicals, phytochemicals and natural resistance modifying agents from Apocynaceae family: possible therapeutic approaches against multidrug resistance in pathogenic microorganisms. Drug Resist Update 51: 100695–100695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas PM, Cristina I, Puentes JP, Costantino FB, Hurrell JA, Pochettino ML (2011) Adaptógenos: plantas medicinales tradicionales comercializadas como suplementos dietéticos en la conurbación Buenos Aires-La Plata (Argentina). Bonplandia 20: 251–264. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas PM, Molares S, Aguilar Contreras A, Doumecq B, Gabrielli F (2013) Ethnobotanical, micrographic and pharmacological features of plant-based weight-loss products sold in naturist stores in Mexico City: the need for better quality control. Acta Bot Bras 27: 560–579. [Google Scholar]

- Arewa OB (2006) TRIPS and traditional knowledge: local communities, local knowledge, and global intellectual property frameworks. Marq Intell Prop L Rev 10: 155. [Google Scholar]

- Arnason T, Hebda RJ, Johns T (1981) Use of plants for food and medicine by Native Peoples of eastern Canada. Can J Bot 59: 2189–2325. [Google Scholar]

- Astutik S, Pretzsch J, Ndzifon Kimengsi J (2019) Asian medicinal plants’ production and utilization potentials: a review. Sustainability 11: 5483. [Google Scholar]

- Augustino S, Gillah PR (2005) Medicinal plants in urban districts of Tanzania: plants, gender roles and sustainable use. Int Forest Rev 7: 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ayam VS (2011) Allium hookeri, Thw. Enum. A lesser known terrestrial perennial herb used as food and its ethnobotanical relevance in Manipur. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev 11: 5389–5412. [Google Scholar]

- Balick MJ, Kronenberg F, Ososki AL, Reiff M, Fugh-Berman A, Roble M, Lohr P, Atha D (2000) Medicinal plants used by Latino healers for women’s health conditions in New York City. Econ Bot 54: 344–357. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Anand U, Ghosh S, Ray D, Ray P, Nandy S, Deshmukh GD, Tripathi V, Dey A (2021) Bacosides from Bacopa monnieri extract: An overview of the effects on neurological disorders. Phytother Res 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Barkaoui M, Katiri A, Boubaker H, Msanda F (2017) Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the traditional treatment of diabetes in Chtouka Ait Baha and Tiznit (Western Anti-Atlas). Morocco J Ethnopharmacol 198: 338–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P, Bloom B, Nahin RL (2008) Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Nat Health Stat Rep 12: 1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellia G, Pieroni A (2015) Isolated, but transnational: the glocal nature of Waldensian ethnobotany, Western Alps, NW Italy. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 11: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BC (2005) Ethnobotany education, opportunities, and needs in the US. Ethnobot Res Appl 3: 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bensoussan A, Talley NJ, Hing M, Menzies R, Guo A, Ngu M (1998) Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with Chinese herbal medicine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 280: 1585–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S (2014) Bioprospecting, biopiracy and food security in India: the emerging sides of neoliberalism. Int Lett Soc Hum Sci 23: 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani K, Gohil V (2010) Natural products drug discovery research in India: status and appraisal. Indian J Exp Biol 48: 199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibi T, Ahmad M, Tareen RB, Tareen NM, Jabeen R, Rehman SU, Sultana S, Zafar M, Yaseen G (2014) Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in district Mastung of Balochistan province-Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol 157: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borza A (1968) Dicţionar etnobotanic: cuprinzînd denumirile populare românești și în alte limbi ale plantelor din România.

- Boyd JM (1984) The role of religion in conservation. Environmentalist 4: 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann RW (2002) Epiphyte diversity in a tropical Andean forest-Reserva Biológica San Francisco, Zamora-Chinchipe, Ecuador. Ecotropica 7: 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bye RA (1986) Medicinal plants of the Sierra Madre: comparative study of Tarahumara and Mexican market plants. Econ Bot 40: 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MON (2005) Sacred Groves for forest conservation in Ghana's coastal savannas: assessing ecological and social dimensions. Singap J Trop Geogr 26: 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Tan NH, Chen JJ, Zeng GZ, Ma YB, Wu YP, Yan H, Yang J, Lu LF, Wang Q (2010) Bioactive flavones and biflavones from Selaginella moellendorffii Hieron. Fitoterapia 81: 253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A (2010) Plantas y Sabiduría Popular del Parque Natural de Montesinho. Un Estudio Etnobotánico en Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Ceuterick M, Vandebroek I, Pieroni A (2011) Resilience of Andean urban ethnobotanies: a comparison of medicinal plant use among Bolivian and Peruvian migrants in the United Kingdom and in their countries of origin. J Ethnopharmacol 136: 27–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceuterick M, Vandebroek I, Torry B, Pieroni A (2008) Cross-cultural adaptation in urban ethnobotany: the Colombian folk pharmacopoeia in London. J Ethnopharmacol 120: 342–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child AB (1993) Religion and Magic in the Life of Traditional Peoples. Pearson College Division.

- Childe VG (1996) The Aryans, Ed 1. Routledge. 10.4324/9781315005256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra RN, Chopra IC, Handa KL, Kapur LD (1958) Indigenous Drugs of India, Ed 2. Academic Publishers, Calcutta, pp. 508–674. [Google Scholar]

- Coady Y, Boylan F (2014) Ethnopharmacology in Ireland: an overview. Rev Bras Farmacogn 24: 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Coder, KD (2011). Cultural Aspects of Trees: Traditions & Myths. https://www.warnell.uga.edu/outreach/publications/individual/cultural-aspects-trees-traditions-myths-0.

- Conde BE, Siqueira AMD, Rogério IT, Marques JS, Borcard GG, Ferreira MQ, Chedier LM, Pimenta DS (2014) Synergy in ethnopharmacological data collection methods employed for communities adjacent to urban forest. Rev Bras Farmacogn 24: 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Coste D, Moore D, Zarate G (2009) Plurilingual and Pluricultural Competence. Council of Europe, Strasbourg. [Google Scholar]

- Coward H (2003) Hindu views of nature and the environment. In Nature Across Cultures. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AB (ed) (2001) Applied Ethnobotany: People, Wild Plant Use and Conservation, Ed 1. Routledge. 10.4324/9781849776073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dafni A (2011) On the present-day veneration of sacred trees in the holy land. Folklore 48: 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dafni A (2006) On the typology and the worship status of sacred trees with a special reference to the Middle East. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahanukar SA, Thatte UM (1997) Current status of ayurveda in phytomedicine. Phytomedicine 4: 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangol D, Maharjan K, Maharjan S, Acharya A (2017) Wild edible plants of Nepal. Conservation and Utilization of Agricultural Plant Genetic Resources in Nepal.

- Das S, Benerjee K, Nandy A, Nath Talapatra S (2015) Assessment of antimutagenic avenue and wild plant diversity on roadside near Nature Park, Kolkata. India Int Lett Nat Sci 2: 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Das T, Anand U, Pandey SK, Ashby Jr CR, Assaraf YG, Chen CS, Dey A (2021) Therapeutic strategies to overcome taxane resistance in cancer. Drug Resist Updat 55: 100754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Ramamurthy PC, Anand U, Singh S, Singh A, Dhanjal DS, Dhaka V, Kumar S, Kapoor D, Nandy S, Kumar M (2021) Wonder or evil?: multifaceted health hazards and health benefits of Cannabis sativa and its phytochemicals. Saudi J Biol Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Day J (2013) Botany meets archaeology: people and plants in the past.J Exp Bot 64: 5805–5816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Albuquerque UP, Hurrell JA (2010) Ethnobotany: one concept and many interpretations. In Recent Developments and Case Studies in Ethnobotany, pp. 87–99.

- de Medeiros PM, Ladio AH, Albuquerque UP (2013) Patterns of medicinal plant use by inhabitants of Brazilian urban and rural areas: a macroscale investigation based on available literature. J Ethnopharmacol 150: 729–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Melo JG, Santos AG, de Amorim ELC, Nascimento SCD, de Albuquerque UP (2011) Medicinal plants used as antitumor agents in Brazil: an ethnobotanical approach. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011: 365359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Werra J (2009) Fighting against biopiracy: does the obligation to disclose in patent applications truly help. Vand J Transnat'l L 42: 143. [Google Scholar]

- Dunagan M (2009) Bioprospection versus biopiracy and the United States versus Brazil: attempts at creating an intellectual property system applicable worldwide when differing views are worlds apart and irreconcilable. Law Bus Rev Am 15: 603. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi OP (1990) Satyagraha for conservation: Awakening the spirit of Hinduism. In Ethics of Environment and Development: Global Challenge, International Response, 201–12.

- Efferth T, Banerjee M, Paul NW, Abdelfatah S, Arend J, Elhassan G, Hamdoun S, Hamm R, Hong C, Kadioglu O et al. (2016) Biopiracy of natural products and good bioprospecting practice. Phytomedicine 23: 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichemberg MT, Amorozo MCDM, Moura LCD (2009) Species composition and plant use in old urban homegardens in Rio Claro, Southeast of Brazil. Acta Bot Bras 23: 1057–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Ellena R, Quave CL, Pieroni A (2012a) Comparative medical ethnobotany of the Senegalese community living in Turin (Northwestern Italy) and in Adeane (Southern Senegal). Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellena R, Quave CL, Pieroni A (2012b) Comparative medical ethnobotany of the Senegalese community living in Turin (Northwestern Italy) and in Adeane (Southern Senegal). Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J (2014) A survey of trees in the Bible. Arboric J 36: 216–226. [Google Scholar]

- Fassina G, Buffa A, Benelli R, Varnier OE, Noonan DM, Albini A (2002) Polyphenolic antioxidant (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate from green tea as a candidate anti-HIV agent. AIDS 16: 939–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo GM, Leitão-Filho H, Begossi A (1993) Ethnobotany of Atlantic forest coastal communities: diversity of plant uses in Gamboa (Itacuruça Island, Brazil). Hum Ecol 2: 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C, Adams J, Frawley J, Hickman L, Sibbritt D (2018) Western herbal medicine consultations for common menstrual problems; practitioner experiences and perceptions of treatment. Phytother Res 32: 531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca FN, Balick MJ (2018) Plant-knowledge adaptation in an urban setting: Candomblé ethnobotany in New York City. Econ Bot 72: 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Framarin C (2014) Hinduism and Environmental Ethics: Law, Literature, and Philosophy. Routledge, pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Frazão-Moreira A (2016) The symbolic efficacy of medicinal plants: practices, knowledge, and religious beliefs amongst the Nalu healers of Guinea-Bissau. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 12: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaoue OG, Coe MA, Bond M, Hart G, Seyler BC, McMillen H (2017) Theories and major hypotheses in ethnobotany. Econ Bot 71: 269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gebreyohannes G, Gebreyohannes M (2013) Medicinal values of garlic: a review. Int J Med Sci 5: 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Group TAP, Chase MW, Christenhusz MJM, Fay MF, Byng JW, Judd WS, Soltis DE et al. (2016) An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot J Linn Soc 181: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Haberman DL (2013) People trees: worship of trees in northern India. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199929177.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halder S, Anand U, Nandy S, Oleksak P, Qusti S, Alshammari EM, Batiha GES, Koshy EP, Dey A (2021) Herbal drugs and natural bioactive products as potential therapeutics: A review on pro-cognitives and brain boosters perspectives. Saudi Pharm J 29: 879–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M (2011) Plants as persons: a philosophical botany. In SUNY Series on Religion and the Environment. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton C (2006) Biodiversity, biopiracy and benefits: what allegations of biopiracy tell us about intellectual property. Dev World Bioeth 6: 158–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto F, Kashiwada Y, Nonaka GI, Nishioka I, Nohara T, Cosentino LM, Lee KH (1996) Evaluation of tea polyphenols as anti-HIV agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 6: 695–700. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández F (1959) Historia Natural de Nueva España.

- Hoareau L, DaSilva EJ (1999) Medicinal plants: a re-emerging health aid. Electron J Biotechnol 2: 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hrynkow C (2017) Nature Worship (Buddhism). In KTS Sarao, JD Long, eds, Buddhism and Jainism. Encyclopedia of Indian Religions. Springer, Dordrecht. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GD, Aboyade OM, Beauclair R, Mbamalu ON, Puoane TR (2015) Characterizing Herbal Medicine Use for Noncommunicable Diseases in Urban South Africa, Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015: 736074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell J (2014) Urban Ethnobotany in Argentina: theoretical advances and methodological strategies. Ethnobiol Conserv 3: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell JA, Pochettino ML (2014) Urban Ethnobotany: theoretical and methodological contributions. In Methods and Techniques in Ethnobiology and Ethnoecology. Humana Press, New York, NY, pp. 293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell J, Puentes J, Arenas P (2015) Medicinal plants with cholesterol-lowering effect marketed in the Buenos Aires-La Plata conurbation, Argentina: an urban ethnobotany study. 4: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jain SK (1994) Ethnobotany and research in medicinal plants in India. Ethnobot Res Appl Search New Drugs 185: 153–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarukamjorn K, Nemoto N (2008) Pharmacological aspects of Andrographis paniculata on health and its major diterpenoid constituent andrographolide. J Health Sci 54: 370–381. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan K (2012) Plants with histories: the changing ethnobotany of Iquito speakers of the Peruvian Amazon. Econ Bot 66: 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Quave CL (2013) A comparison of traditional food and health strategies among Taiwanese and Chinese immigrants in Atlanta, Georgia. USA J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 9: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar C, Gupta A, Kanjilal S, Katiyar S (2012) Drug discovery from plant sources: an integrated approach. Ayu 33: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul MK, Sharma PK, Singh V (1991) Contribution to the ethnobotany of Padaris of Doda in Jammu & Kashmir State, India. Nelumbo 33: 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler C, Wischnewsky M, Michalsen A, Eisenmann C, Melzer J (2013) Ayurveda: between religion, spirituality, and medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013: 952432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic O, Bagci E (2013) An ethnobotanical survey of some medicinal plants in Keban (Elazığ-Turkey). J Med Plants Res 7: 1675–1684. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber AL (1920) Totem and taboo: an ethnologic psychoanalysis. Am Anthropol 22: 48–55. 10.1525/aa.1920.22.1.02a00050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar VS, Navaratnam V (2013) Neem (Azadirachta indica): prehistory to contemporary medicinal uses to humankind. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 3: 505–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunert O, Swamy RC, Kaiser M, Presser A, Buzzi S, Rao AA, Schühly W (2008) Antiplasmodial and leishmanicidal activity of biflavonoids from Indian Selaginella bryopteris. Phytochem Lett 1: 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ladio AH, Albuquerque UP (2014) The concept of hybridization and its contribution to urban ethnobiology. Ethnobiol Conserv 3: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lagunin AA, Goel RK, Gawande DY, Pahwa P, Gloriozova TA, Dmitriev AV, Ivanov SM, Rudik AV, Konova VI, Pogodin PV et al. (2014) Chemo-and bioinformatics resources for in silico drug discovery from medicinal plants beyond their traditional use: a critical review. Nat Prod Rep 31: 1585–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara Reimers EA, Lara Reimers DJ, Chaloupkova P, Zepeda del Valle JM, Milella L, Russo D (2019) An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico. Plan Theory 8: 246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitão F, Fonseca-Kruel VSD, Silva IM, Reinert F (2009) Urban ethnobotany in Petrópolis and Nova Friburgo (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Rev Bras Farmacogn 19: 333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Lind BK, Diehr PK, Grembowski DE, Lafferty WE (2009) Chiropractic use by urban and rural residents with insurance coverage. J Rural Health 25: 253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Lu H, Zhao Q, He Y, Niu J, Debnath AK, Wu S, Jiang S (2005) Theaflavin derivatives in black tea and catechin derivatives in green tea inhibit HIV-1 entry by targeting gp41. Biochim Biophys Acta 1723: 270–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh CH (2009) Use of traditional Chinese medicine in Singapore children: perceptions of parents and paediatricians. Singapore Med J 50: 1162–1168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longrigg J (2013) Greek rational medicine: philosophy and medicine from Alcmaeon to the Alexandrians. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj Ł, Nieroda Z (2011) Collecting and learning to identify edible fungi in southeastern Poland: age and gender differences. Ecol Food Nutr 50: 319–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj ŁJ, Kujawska M (2012) Botanists and their childhood memories: an underutilized expert source in ethnobotanical research. Bot J Linn Soc 168: 334–343. [Google Scholar]

- Macía MJ, García E, Vidaurre PJ (2005) An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants commercialized in the markets of La Paz and El Alto. Bolivia J Ethnopharmacol 97: 337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]