Abstract

Background

Newly emerged mutations within the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) can confer piperaquine resistance in the absence of amplified plasmepsin II (pfpm2). In this study, we estimated the prevalence of co-circulating piperaquine resistance mutations in P. falciparum isolates collected in northern Cambodia from 2009 to 2017.

Methods

The sequence of pfcrt was determined for 410 P. falciparum isolates using PacBio amplicon sequencing or whole genome sequencing. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was used to estimate pfpm2 and pfmdr1 copy number.

Results

Newly emerged PfCRT mutations increased in prevalence after the change to dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in 2010, with >98% of parasites harboring these mutations by 2017. After 2014, the prevalence of PfCRT F145I declined, being outcompeted by parasites with less resistant, but more fit PfCRT alleles. After the change to artesunate-mefloquine, the prevalence of parasites with amplified pfpm2 decreased, with nearly half of piperaquine-resistant PfCRT mutants having single-copy pfpm2.

Conclusions

The large proportion of PfCRT mutants that lack pfpm2 amplification emphasizes the importance of including PfCRT mutations as part of molecular surveillance for piperaquine resistance in this region. Likewise, it is critical to monitor for amplified pfmdr1 in these PfCRT mutants, as increased mefloquine pressure could lead to mutants resistant to both drugs.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, malaria, piperaquine resistance, chloroquine resistance transporter, Cambodia

As of 2017, newly emerged piperaquine-resistant PfCRT mutants were nearly fixed in northern Cambodia, with nearly half having single-copy pfpm2. These results emphasize the importance of including PfCRT mutations in molecular surveillance for piperaquine resistance in this region.

The burden of malaria has been greatly reduced over the past decade, owing in part to the implementation of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) and other interventions aimed at controlling and eventually eliminating malaria [1]. In the Greater Mekong Subregion, where intensive malaria elimination efforts are ongoing, the number of malaria cases and deaths decreased by 74% and 91%, respectively, between 2012 and 2016 [1]. However, this progress is threatened by the emergence of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum that has become well-established in the eastern Greater Mekong Subregion [2, 3].

The artemisinin derivatives are fast-acting antimalarials that are recommended to be used in combination with a longer-acting partner drug to deter the emergence of resistance [4]. However, delayed clearance of parasitemia following treatment with artemisinin derivatives and ACTs began to be reported in Western Cambodia around 2007–2008 [5, 6], indicating the possible emergence of artemisinin resistance. In response to these reports, Cambodian officials changed the first-line therapy for P. falciparum malaria in 2010 from artesunate-mefloquine to dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHA-PPQ); however, by 2012, treatment failures with DHA-PPQ began to be reported [7–9]. The high rate of DHA-PPQ treatment failures, as well as the reduced prevalence of parasites with amplified pfmdr1 copy number (associated with mefloquine resistance [10]), eventually led to another drug policy change, back to artesunate-mefloquine, in 2016 [11].

Genome-wide association studies of the genetic basis of piperaquine resistance initially identified an association between amplified copy number of the plasmepsin II gene (pfpm2) and decreased parasite susceptibility to piperaquine [12, 13]. However, subsequent studies identified mutations within the P. falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) that were associated with reduced susceptibility to piperaquine [14–16]. These mutations were different than those linked to chloroquine resistance and tended to occur in parasites with amplified pfpm2. Some mutations also seemed to confer an additional degree of resistance beyond that conferred by pfpm2 amplification alone [15]. Gene editing studies demonstrated that these newly emerged PfCRT mutations could confer piperaquine resistance in the absence of pfpm2 amplification, although often at a fitness cost [17]. In addition, different PfCRT mutations conferred different levels of resistance, as well as different fitness costs to the parasite [17, 18]. However, because fitness is relative to environment, it is difficult to predict how the interplay between resistance and fitness of parasites with these newly emerged PfCRT mutations will impact the selection on these mutations in a field setting in the face of changing first-line drug policies.

To understand the complex interactions of co-circulating resistance mutations and the impact of drug policy changes on the prevalence of different alleles, we examined the prevalence of piperaquine-resistance mutations in P. falciparum isolates collected in Oddar Meanchey Province in northern Cambodia from 2009 to 2017 and the association of these markers with ex vivo piperaquine susceptibility.

METHODS

Study Samples

Samples were collected as part of a malaria survey conducted from 2009 to 2017 by the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences (AFRIMS) [19], as well as from drug efficacy trials conducted at the same site [8, 20]. Sample collection was conducted with informed consent under protocols approved by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and local ethics committees. Parasite genotyping and sequencing were performed with approval of the institutional review boards at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the University of North Carolina under an established Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with AFRIMS. All samples were collected from individuals with clinical P. falciparum malaria confirmed by blood smear microscopy.

DNA Isolation

Genomic DNA was extracted from 1 mL of leukocyte-depleted venous blood using a Qiagen DNA Midi Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Extracted DNA was quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, San Jose, California).

Gene Copy Number

A SYBR Green–based quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay [12] was used to estimate copy number of the pfmdr1 (PF3D7_0523000) and pfpm2 (PF3D7_1408000) genes using a Light Cycler 96 (Roche). qPCR was carried out in a 20-µL reaction in 96-well plates using 5X HOT FIREPol EvaGreen qPCR Mix plus (Solis BioDyne, Estonia). Forward and reverse primers were used at 0.3 µM, with 1.5 µL of template DNA. Copy number was estimated in duplicate based on a 4-point standard curve generated by mixing synthetic fragments of each gene of interest with the pfβ -tubulin gene [12] (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). The NF54 strain of P. falciparum, which contains 1 copy of pfmdr1 and pfpm2, was used as a control. Copy number was calculated using the 2-Δct method, as described previously [12]. Copy number estimates were rounded up to the next whole number if the fraction of a copy was >0.6 (ie, samples with copy number >1.6 would be rounded to 2, >2.6 rounded to 3, etc). Amplification efficiencies of pfmdr1 and pfpm2 were similar to pf-tubulin (Supplementary Figures 3 and 4). Samples with threshold cycles >40 or minimal end point fluorescence <2 were excluded from further analysis.

Pfcrt Amplicon Sequencing

PCR

The pfcrt gene was amplified using a conventional nested PCR. Primary PCR primers were designed to bind –86 base pairs (bp) upstream (accession: LR131487 region: 391 965 to 391 989) and +596 bp downstream (accession: LR131487 region: 395 725 to 395 743) of the pfcrt gene and included a universal tag. Secondary primers were provided by Pacific Biosciences (Menlo Park, California) and consisted of a sequence complementary to the universal tag of the primary primers plus a unique barcode for each of the 96 primer pairs. Primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

The primary PCR was performed using TaKaRa Ex Taq DNA Polymerase (Hot-Start). Reactions were 25 µL in volume and included 0.05 U/µL TaKaRa Ex Taq HS polymerase, 0.4 mM dNTPs, 2 mM 10× ExTag Buffer (Mg2+ plus), and 0.05 µM primers. Primary PCR cycling conditions included enzyme activation at 94°C for 2 minutes, 30 cycles of denaturation at 96°C for 20 seconds and annealing and elongation at 59.9°C for 4 minutes, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes.

Secondary PCR was performed using TaKaRa Ex Taq DNA Polymerase (Hot-Start) in a 50-µL reaction using the same concentrations of reagents (double volume) used in the primary PCR. Secondary PCR cycling conditions included enzyme activation at 94°C for 2 minutes, 20 cycles of denaturation at 96°C for 20 seconds and annealing and elongation at 61°C for 4 minutes, and a final elongation at 72°C for 10 minutes.

Sample Preparation and PacBio Sequencing

Prior to sequencing, PCR products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel and purified using a QIAquick 96 PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Purified products were quantified using Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit and pooled in equimolar concentration, with 96 products with unique bar codes per pool. The quality and quantity of pooled amplicons were determined using Agilent 2200 TapeStation. Amplicons <100 bp in size were removed by AMPure purification (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, Indiana). Amplicon sequencing was performed using a PacBio RSII (Pacific Biosciences).

Whole Genome Sequencing and Concordance With PacBio Results

DNA libraries were constructed using the KAPA Library Preparation Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, Massachusetts). DNA (≥200 ng) was fragmented with the Covaris E210 to approximately 200 bp. Libraries were prepared using a modified version of the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA was purified between enzymatic reactions and library size selection was performed with AMPure XT beads. Libraries were assessed for concentration and fragment size using the DNA High Sensitivity Assay on the LabChip GX (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, Massachusetts), and were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 (Illumina, San Diego, California) to generate 150 bp paired-end reads.

Out of 410 isolates, 202 were genotyped by PacBio amplicon sequencing, 87 were genotyped from whole genome sequencing data, and 121 were genotyped by both PacBio and whole genome sequencing. Samples genotyped by both approaches were used to verify the concordance of calls of the predominant allele (>0.70). Concordance between calls averaged 99.5% (range, 98%–100%).

Variant Calling

PacBio Data

PacBio sequencing data were processed using Circular Consensus Sequence analysis in SMRT Link (version 6.0.0) [21] and mapped to the 3D7 reference using BWA-MEM [22]. Binary Alignment Map (BAM) files were processed using GATK Best Practices workflow [23, 24]. Bedtools [25] was used to generate coverage and depth estimates from the processed reads.

Whole Genome Sequencing Data

Sequencing data were analyzed by mapping raw fastq files to the 3D7 reference genome using Bowtie2 [26]. The BAM files were processed using the GATK Best Practices workflow to obtain analysis-ready reads [23, 24]. Bedtools [25] was used to generate coverage and depth estimates from the processed reads.

Variant Calling and Quality Control

The GATK Best Practices workflow was followed for variant calling [23, 24]. Haplotype Caller was used to create genomic variant call format files for each sample and joint SNP calling was performed (GATK version 4.1). Variants were removed if they met the following filtering criteria: variant confidence/quality by depth <2.0, strand bias >60.0, root mean square of the mapping quality <40.0, mapping quality rank sum < –12.5, read position rank sum < –8.0, quality <50. The predominant allele (frequency >70%) was called at each polymorphic site. Sites lacking a predominant allele were labeled as missing. Variant sites with >20% missing calls and samples with >20% missing data were excluded from the analysis. Variant sites with read depth <5× were also excluded from the analysis.

Piperaquine Susceptibility Testing

Ex vivo piperaquine 90% inhibitory concentrations (IC90) were assessed using a histidine-rich protein 2 (HRP-2) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously described [27, 28] Assays were performed at AFRIMS. Piperaquine concentrations in the assay ranged from 0.9 to 674 nM including a no drug control. Beginning in 2014, an increased range of piperaquine concentrations (3.4–53 905 nM) was used in addition to the standard dilutions. To estimate piperaquine IC90 of parasites that grew in the maximum concentration of drug from the standard range (0.9–674 nM), the curves were replotted by fitting “zero-growth” HRP-2 OD values at the extrapolated piperaquine concentration of 53 905 nM. Dose-response curves for isolates with a range of susceptibilities have been described previously [20, 27].

Statistical Analysis

The prevalence of different drug resistance mutations was estimated as the number of parasites with a given mutation divided by the total number of parasites genotyped. Isolates missing calls at polymorphic sites within PfCRT were excluded, as the unique haplotype could not be resolved. IC90 values were log-transformed, and differences in mean IC90 between isolates with different combinations of mutations were determined by t test or linear regression. Differences based on categorical variables were determined using a χ 2 test or logistic regression. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software.

RESULTS

Parasite Genotypes

Of the 442 parasite isolates from Oddar Meanchey province from 2009 to 2017, 414 were successfully genotyped for pfmdr1 and pfpm2 copy number and PfCRT mutations. As the number of isolates available in 2011 and 2012 was too small for reliable estimates of prevalence (n = 3 and n = 1, respectively), the isolates from these years were excluded from analysis. Again, owing to small sample size (n = 17) and because all 2016 isolates were sampled during the last quarter of the year, these isolates were combined with isolates from 2017 for estimation of mutation prevalence over time.

Newly Emerged PfCRT Mutations

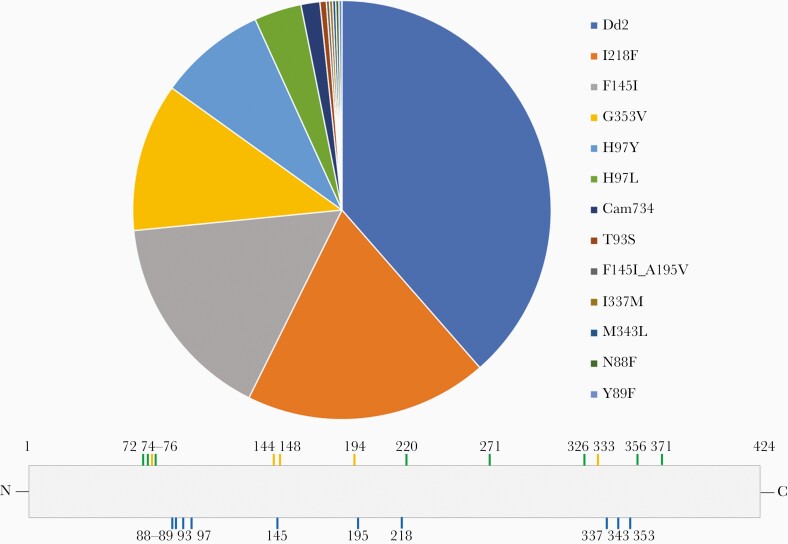

The prevalence of newly emerged PfCRT mutations (ie, mutations not associated with chloroquine resistance), as well as the Dd2 and Cam734 haplotypes, among the genotyped isolates collected from 2009 to 2017 is shown in Figure 1. PfCRT mutations at positions 97, 145, 218, and 353 were most prevalent, while mutations at positions 88, 89, 337, and 343 were only observed once in the data set. These mutations occurred on a Dd2 background, which contains mutations at positions 75, 76, 220, 271, 326, 356, and 371 (Figure 1). Only 1 parasite showed the presence of 2 new PfCRT mutations, at positions 145 and 195. Examination of the long-read sequence data suggested that this finding was not an artefact of alleles called from a polyclonal infection and that these mutations were found in the same haplotype.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of newly emerged Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) mutations in P. falciparum isolates collected from 2009 to 2017. Pie chart represents prevalence estimates from the complete data set (N = 410), regardless of year. The PfCRT protein schematic indicates the location of PfCRT mutations. Mutations observed in the Dd2 (green) and Cam734 (orange) haplotypes are shown at the top, while newly emerged PfCRT mutations (blue) are shown at the bottom.

Ex Vivo Piperaquine Susceptibility of Parasites With Newly Emerged PfCRT Mutations

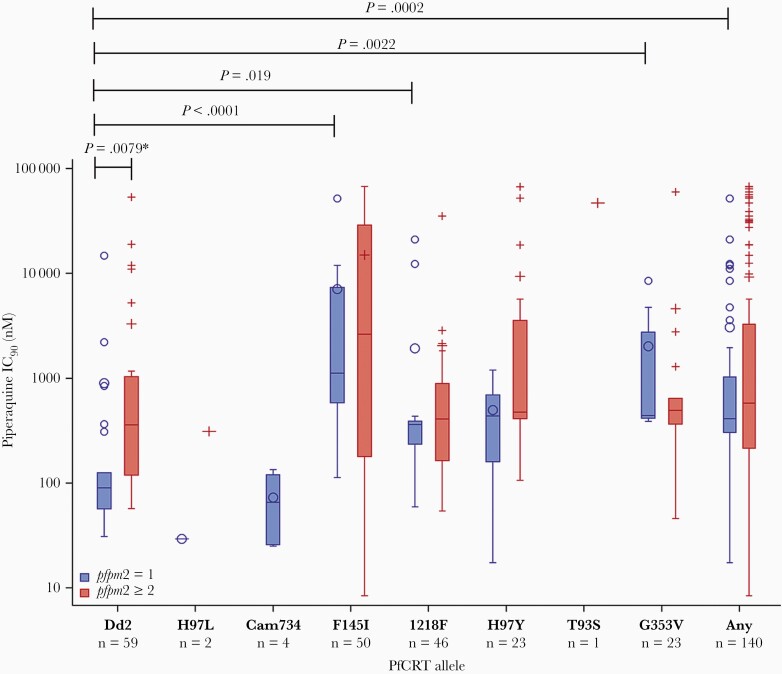

The distribution of ex vivo piperaquine IC90 values for parasites with newly emerged PfCRT mutations with or without amplified pfpm2 is shown in Figure 2. Parasites with the Dd2 haplotype and pfpm2 amplification had significantly greater mean log10-transformed piperaquine IC90 compared to Dd2 parasites without pfpm2 amplification (t test, P = .0079). In parasites with newly emerged PfCRT mutations, mean log10-transformed piperaquine IC90 was not significantly different between parasites with or without pfpm2 amplification. In parasites with single-copy pfpm2, those with the PfCRT F145I, G353V, or I218F mutations had a significantly greater log10-transformed piperaquine IC90 compared to Dd2 (linear regression; P < .0001, P = .0022, and P = .019, respectively), while other mutations did not show a significant difference in piperaquine IC90 compared to Dd2 (perhaps owing to smaller sample size). Parasites with PfCRT F145I, G353V, or I218F also had significantly lower log10-transformed chloroquine IC50 compared to Dd2 parasites (linear regression P < .0001 for all 3 comparisons), while parasites with H97Y had significantly greater log10-transformed chloroquine IC50 compared to Dd2 parasites (linear regression, P = .033) (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Ninety percent inhibitory concentrations (IC90) to piperaquine in parasites with newly emerged Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) mutations, with and without pfpm2 amplification. PfCRT mutations are shown on the x-axis, and piperaquine IC90 is shown on the y-axis (log10 scale). Blue box plots show the IC90 distribution for parasites with single-copy pfpm2, while red box plots show the IC90 distribution for parasites with amplified pfpm2. The “Any” category includes parasites with any of the following PfCRT mutations: F145I, H97Y, G353V, I218F, or T93S. The asterisked P value was estimated using a t test, while the other P values were estimated using linear regression, with the Dd2 haplotype serving as the reference. Only statistically significant P values (P < .05) are shown.

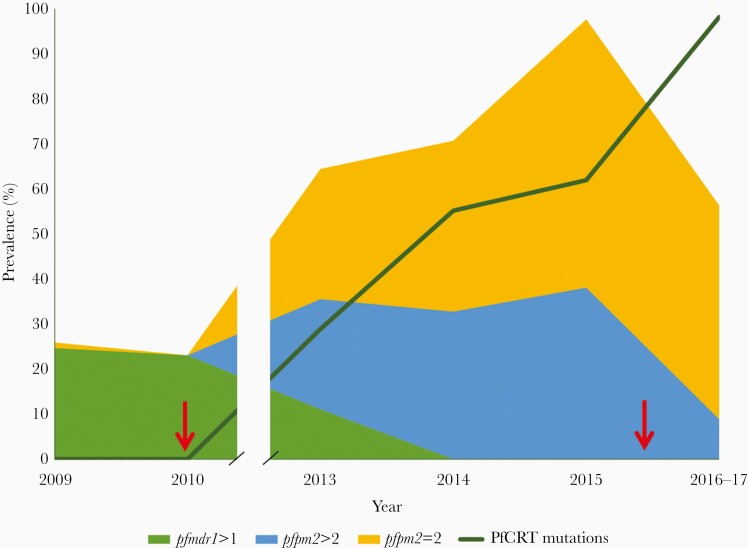

Prevalence of Drug Resistance Markers Over Time

The prevalence of parasites having newly emerged PfCRT mutations associated with piperaquine resistance, amplified pfpm2 copy number, or amplified pfmdr1 copy number over time is shown in Figure 3. The prevalence of parasites with any one of the newly emerged PfCRT mutations associated with piperaquine resistance increased after 2010 through 2017. Nearly all parasite isolates containing PfCRT mutations associated with piperaquine resistance (98.6%) also harbored a Kelch13 C580Y mutation, with the remaining isolates (n = 3) containing wild-type Kelch13. The prevalence of parasites with amplified pfmdr1 copy number decreased after 2010, reaching zero prevalence by 2014. The prevalence of parasites with amplified pfpm2 increased after 2010 through 2015, but decreased by 2017, with the greatest decrease in prevalence of parasites with pfpm2 copy number >2. This decrease in prevalence of amplified pfpm2 was observed regardless which PfCRT mutation was present, with parasites harboring PfCRT F145I, I218F, and H97Y all showing decreased prevalence of pfpm2 amplification in 2017 compared to 2015 (Supplementary Figure 6). After adjusting for year, there was no significant difference in the odds of pfpm2 amplification in parasites with PfCRT G353V, H97Y, or I218F compared to F145I (logistic regression, P = .060, P = .14, and P = .94, respectively). Nearly half of parasite isolates sampled in 2017 (44%) had a single copy of pfpm2, and 98.5% of those isolates harbored a PfCRT mutation that has been associated with piperaquine resistance.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of antimalarial drug resistance mutations over time in Oddar Meanchey Province, Cambodia, 2009–2017. The green area represents the prevalence of amplified pfmdr1, while the gold and blue areas represent the prevalence of parasites with 2 or >2 copies of pfpm2, respectively. The dark green line indicates the prevalence of parasites harboring a Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) mutation associated with piperaquine resistance, including T93S, H97Y, F145I, I218F, or G353V. Red arrows indicate years when the first-line drug treatment changed, with the switch to dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine occurring in 2010 and to artesunate-mefloquine in 2016.

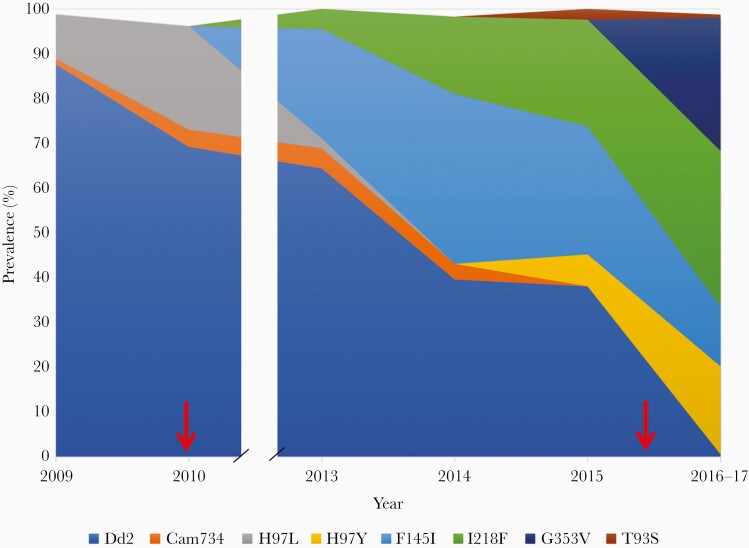

Temporal Dynamics of Newly Emerged PfCRT Alleles Associated With Piperaquine Resistance

The prevalence of PfCRT alleles observed in Oddar Meanchey Province over time is plotted in Figure 4 (Supplementary Table 2). The prevalence of the piperaquine-sensitive Dd2 haplotype decreased steadily over time, reaching almost zero by 2017. The PfCRT H97L mutation was replaced by the H97Y mutation beginning in 2014, with H97Y increasing in prevalence through 2017. The PfCRT F145I mutation rapidly increased in prevalence after 2010 through 2014, but then decreased in prevalence through 2017. The PfCRT I218F mutation also increased in prevalence after 2010, although more slowly than F145I, and continued to increase in prevalence through 2017. The G353V mutation is not observed until 2017, at which point it is found in 30% of isolates. The PfCRT T93S mutation had a very low prevalence in this province over the time frame studied.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of newly emerged Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter mutations over time in Oddar Meanchey Province, Cambodia, 2009–2017. The area represents the proportion of isolates comprised of each mutation by year according to color. Mutations present in ≤2 isolates in the data set were not plotted. Red arrows indicate years when the first-line drug treatment changed, with the switch to dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine occurring in 2010 and to artesunate-mefloquine in 2016.

DISCUSSION

To understand the dynamics of co-circulating resistance mutations and the impact of drug policy changes on the prevalence of different alleles, we examined the prevalence of piperaquine-resistance mutations in P. falciparum isolates collected in Oddar Meanchey Province in northern Cambodia from 2009 to 2017. Over this time frame we observed P. falciparum isolates with 10 different newly emerged PfCRT mutations (ie, mutations not previously associated with chloroquine resistance), 6 of which have been identified in previous studies as being associated with piperaquine resistance [14–17, 29]. Amplification of pfpm2 did not seem to impart an additional degree of resistance to these PfCRT mutants, based on a comparison of IC90 values between parasites harboring these PfCRT mutations either with or without pfpm2 amplification. In the absence of pfpm2 amplification, parasites with the F145I, I218F, and G353V mutations had significantly higher IC90 values compared to parasites with the Dd2 PfCRT haplotype, with F145I mutants displaying the highest mean IC90 values. The prevalence of parasites with piperaquine resistance-associated PfCRT mutations increased after 2010, with the Dd2 piperaquine-sensitive haplotype virtually disappearing by 2017; however, specific PfCRT mutations, namely the F145I mutation, decreased in prevalence in more recent time frames, consistent with a drug policy change from DHA-PPQ to artesunate-mefloquine in 2016. In addition, the prevalence of parasites with pfpm2 amplification decreased after the drug policy change in 2016, with nearly half of PfCRT mutants having single-copy pfpm2 in 2017.

Although some of the same mutations have been observed at this study site as in other locations [16, 17], the dynamics of when these mutations were first observed and which mutations predominate differ by site. For example, at the study sites in western Cambodia examined by Ross et al, the M343L and G353V mutations initially predominated, with the F145I and H97Y mutations not being observed until later years [17], while at the site in northern Cambodia examined in our study, the F145I and I218F alleles emerged first, with the G353V mutation observed later in 2017. Although only presented in aggregate, the T93S mutation showed a high prevalence (~20%) at study sites examined by Hamilton et al in 2016–2017 [16]; however, T93S had a very low prevalence at our study sites in Oddar Meanchey province during the same time frame (<3%). Further investigation will be required to understand the origins and spread of these newly emerged PfCRT mutations, an analysis that will likely be complicated by the recent selection by piperaquine and the presence of an existing sweep at the PfCRT locus driven by chloroquine resistance.

Although the F145I mutation seems to confer a greater degree of resistance to the parasite compared to other newly emerged PfCRT mutations, gene editing studies have suggested that this mutation confers a greater fitness cost to the parasite compared to other newly emerged PfCRT mutations [17, 18], likely owing to its location in the protein [30]. This reduced fitness is consistent with the decrease in prevalence of parasites with this mutation in recent time frames, with other, more fit PfCRT mutants outcompeting these parasites in the face of reduced piperaquine pressure following the drug policy change back to artesunate-mefloquine. Despite conferring a lesser degree of resistance to piperaquine compared to F145I, parasites with the I218F and G353V mutations displayed a significantly greater mean IC90 to piperaquine compared to parasites with the Dd2 PfCRT haplotype, in the absence of pfpm2 amplification. The prevalence of these parasites remained high and increased through 2017, perhaps owing to a lack of Dd2-type parasites in the population to outcompete these parasites in an environment of reduced drug pressure (ie, piperaquine resistance mutants are fixed in the population), incomplete or delayed implementation of new drug policies, or to the continued use of DHA-PPQ in neighboring regions of Thailand until 2019. Continued monitoring of parasite populations from this area will be necessary to determine whether these PfCRT mutants decrease in prevalence in subsequent years.

The prevalence of parasites with pfpm2 amplification, the primary marker used to estimate the extent of piperaquine resistance in a population, has decreased since 2016, consistent with a removal of DHA-PPQ as the first-line therapy. The prevalence of parasites with pfpm2 copy number >2 has decreased most substantially and across all alleles, even those deemed less fit in other studies [18]. In fact, nearly half of parasites harboring a PfCRT mutation associated with piperaquine resistance have single-copy pfpm2. This finding has important implications for surveillance and selection of multidrug resistance. First, this finding suggests that pfpm2 amplification alone may not capture the true extent of piperaquine resistance in a population, as a large proportion of PfCRT mutants in recent years lack pfpm2 amplification [31]. Second, pfpm2 amplification is thought to be incompatible with pfmdr1 amplification [12, 32] (associated with resistance to mefloquine [10]), suggesting possible antagonistic resistance mechanisms that have served as the premise for triple combination therapies [33]). However, as piperaquine-resistant PfCRT mutants now increasingly have single-copy pfpm2, and the first-line therapy has been changed back to artesunate-mefloquine, these parasites may be able to acquire pfmdr1 amplification, yielding parasites resistant to both therapies or to triple ACTs that include both mefloquine and piperaquine.

CONCLUSIONS

This study has demonstrated the temporal dynamics of PfCRT mutations associated with piperaquine resistance in the Oddar Meanchey Province of northern Cambodia. The large proportion of piperaquine-resistant PfCRT mutants that lack pfpm2 amplification emphasizes the importance of including PfCRT mutations as part of molecular surveillance for piperaquine resistance in this region. Likewise, in the face of the change in first-line therapy to artesunate-mefloquine, it is critical to be vigilant in monitoring for amplified pfmdr1 in PfCRT mutants, particularly those lacking amplified pfpm2, as increased mefloquine pressure could lead to selection for mutants resistant to both piperaquine and mefloquine.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. Conceived and designed the study: B. S., J. T. L., and S. T.-H. Collected and provided the samples: D. S., C. L., So. C., S. S., Pr. S., D. L., H. R., S. D. T., C. A. L., M. D. S., M. W., D. L. S., P. L. S., and N. C. W. Generated sequencing, genotyping, or drug susceptibility data: B. S., Pi. S., C. C., Su. C., C. P., N. B., P. L., M. A., M. D.-F., P. G., and B. A. V. Analyzed the data: B. S., Z. S., A. P. M., and S. T.-H. Interpreted the results: B. S., M. D. S., M. W., J. T. L., N. C. W., and S. T.-H. Wrote the manuscript: B. S. and S. T.-H. All authors have read and had the opportunity to comment on the manuscript.

Acknowledgments. We thank the study participants in Cambodia, as well as the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences (AFRIMS) field teams and laboratory staff who collected the samples and generated the ex vivo drug susceptibility data. We thank Dr Joana C. Silva for helpful comments on the manuscript and guidance on sequencing procedures. PfCRT sequences are available in GenBank (accession numbers MW274754–MW275076). Whole genome sequencing reads have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information short-read archive (accession numbers SAMN17028801–SAMN17028887).

Disclaimer. The manuscript has been reviewed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. There is no objection to its presentation and/or publication. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors, and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting true views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense. The investigators have adhered to the policies for protection of human subjects as prescribed in AR 70–25.

Financial support. This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01AI125579 to S. T.-H.) and by the United States Department of Defense Global Emerging Infections Surveillance Program to AFRIMS.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

The authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: Annual Meeting of the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, National Harbor, Maryland, November 2019.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2018. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malariareport-2018/en/. Accessed 09 February 2021.

- 2. Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:411– 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Imwong M, Suwannasin K, Kunasol C, et al. The spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in the Greater Mekong subregion: a molecular epidemiology observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:491– 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woodrow CJ, White NJ. The clinical impact of artemisinin resistance in Southeast Asia and the potential for future spread. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2017; 41:34– 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, Smith BL, Socheat D, Fukuda MM. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:2619– 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:455– 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a multisite prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:357– 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Spring MD, Lin JT, Manning JE, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure associated with a triple mutant including kelch13 C580Y in Cambodia: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:683– 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saunders DL, Vanachayangkul P, Lon C, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure in Cambodia. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:484– 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Price RN, Uhlemann AC, Brockman A, et al. Mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and increased pfmdr1 gene copy number. Lancet 2004; 364:438– 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization. Status report on artemisinin and ACT resistance (April 2016). http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/update-artemisinin-resistance-april2016/en/. Accessed 09 February 2021.

- 12. Witkowski B, Duru V, Khim N, et al. A surrogate marker of piperaquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a phenotype-genotype association study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:174– 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amato R, Lim P, Miotto O, et al. Genetic markers associated with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a genotype-phenotype association study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:164– 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duru V, Khim N, Leang R, et al. Plasmodium falciparum dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failures in Cambodia are associated with mutant K13 parasites presenting high survival rates in novel piperaquine in vitro assays: retrospective and prospective investigations. BMC Med 2015; 13:305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Agrawal S, Moser KA, Morton L, et al. Association of a Novel Mutation in the Plasmodium falciparum Chloroquine Resistance Transporter With Decreased Piperaquine Sensitivity. J Infect Dis 2017; 216:468––76.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamilton WL, Amato R, van der Pluijm RW, et al. Evolution and expansion of multidrug-resistant malaria in southeast Asia: a genomic epidemiology study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:943– 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ross LS, Dhingra SK, Mok S, et al. Emerging Southeast Asian PfCRT mutations confer Plasmodium falciparum resistance to the first-line antimalarial piperaquine. Nat Commun 2018; 9:3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dhingra SK, Small-Saunders JL, Menard D, Fidock DA. Plasmodium falciparum resistance to piperaquine driven by PfCRT. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:1168– 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chaorattanakawee S, Saunders DL, Sea D, et al. Ex Vivo Drug Susceptibility Testing and Molecular Profiling of Clinical Plasmodium falciparum Isolates from Cambodia from 2008 to 2013 Suggest Emerging Piperaquine Resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:4631– 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wojnarski M, Lon C, Vanachayangkul P, et al. Atovaquone-Proguanil in Combination With Artesunate to Treat Multidrug-Resistant P. falciparum Malaria in Cambodia: An Open-Label Randomized Trial. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pacific Biosciences. SMRT® Tools Reference Guide, 2018. https://www.pacb.com/wp-content/uploads/SMRT_Tools_Reference_Guide_v600.pdf. Accessed 09 February 2021.

- 22. Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM,2013. http://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997. Accessed 09 February 2021.

- 23. DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 2011; 43:491– 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2013; 11:11 0 1–0 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010; 26:841– 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012; 9:357– 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chaorattanakawee S, Lon C, Jongsakul K, et al. Ex vivo piperaquine resistance developed rapidly in Plasmodium falciparum isolates in northern Cambodia compared to Thailand. Malar J 2016; 15:519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rutvisuttinunt W, Chaorattanakawee S, Tyner SD, et al. Optimizing the HRP-2 in vitro malaria drug susceptibility assay using a reference clone to improve comparisons of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates. Malar J 2012; 11:325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van der Pluijm RW, Imwong M, Chau NH, et al. Determinants of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: a prospective clinical, pharmacological, and genetic study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:952– 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim J, Tan YZ, Wicht KJ, et al. Structure and drug resistance of the Plasmodium falciparum transporter PfCRT. Nature 2019; 576:315– 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boonyalai N, Vesely BA, Thamnurak C, et al. Piperaquine resistant Cambodian Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates: in vitro genotypic and phenotypic characterization. Malar J 2020; 19:269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Veiga MI, Ferreira PE, Malmberg M, et al. pfmdr1 amplification is related to increased Plasmodium falciparum in vitro sensitivity to the bisquinoline piperaquine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:3615– 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van der Pluijm RW, Tripura R, Hoglund RM, et al. Triple artemisinin-based combination therapies versus artemisinin-based combination therapies for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a multicentre, open-label, randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2020; 395:1345– 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.