A supercontinuum source based on a 1-mm2 Si3N4 chip offers improved OCT imaging performance over commercial supercontinuum sources.

Abstract

Supercontinuum sources for optical coherence tomography (OCT) have raised great interest as they provide broad bandwidth to enable high resolution and high power to improve imaging sensitivity. Commercial fiber-based supercontinuum systems require high pump powers to generate broad bandwidth and customized optical filters to shape/attenuate the spectra. They also have limited sensitivity and depth performance. We introduce a supercontinuum platform based on a 1-mm2 Si3N4 photonic chip for OCT. We directly pump and efficiently generate supercontinuum near 1300 nm without any postfiltering. With a 25-pJ pump pulse, we generate a broadband spectrum with a flat 3-dB bandwidth of 105 nm. Integrating the chip into a spectral domain OCT system, we achieve 105-dB sensitivity and 1.81-mm 6-dB sensitivity roll-off with 300-μW optical power on sample. We image breast tissue to demonstrate strong imaging performance. Our chip will pave the way toward portable OCT and incorporating integrated photonics into optical imaging technologies.

INTRODUCTION

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a high-resolution, label-free, three-dimensional optical imaging modality (1). OCT has become the standard of care in medical specialties such as ophthalmology (1–6) and dermatology (7–9) and is an emerging imaging technology in other areas such as gastroenterology (10–12) and breast cancer imaging (13–15). Supercontinuum light sources for OCT offer broad bandwidth and excellent spatial coherence (16–22), but they require very high power to achieve broad bandwidth and strong performance in terms of sensitivity and sensitivity roll-off range, and the spectrum needs to be shaped and attenuated with conventional bulk optical filters. Fibers used in commercial systems require high optical pump powers (23) to generate supercontinuum, which, in turn, requires complex optical filters to attenuate the power to meet radiation safety standards for medical imaging and not saturate or damage the camera detector. In addition, commercial supercontinuum sources can suffer from excess noise that limits OCT performance in terms of sensitivity and depth performance (sensitivity roll-off range) (24–26). The excess noise increases exponentially with imaging speed (27), which is particularly disadvantageous in clinical settings where fast imaging speeds are required. Moreover, commercial supercontinuum sources are bulky in size, not to mention that they require additional optical filtering setups, which further limits their practicality. Efforts have been made to develop supercontinuum sources for OCT centered at 1300 nm, which is one of the common imaging wavelengths (19, 23–25, 28–32); all-normal-dispersion (ANDi) fibers have also been proposed to reduce the excess noise, but they still need filters and have limited sensitivity and depth performance (sensitivity roll-off) (25, 26, 33, 34) and have not been widely used in commercial systems. For example, the NKT Photonics SuperK Extreme, the most common commercial supercontinuum source used in OCT imaging applications, has high excess noise leading to low-sensitivity and poor-sensitivity roll-off performance, especially when imaging at high speeds. With 4-mW power on the sample, the maximum sensitivity achieved is 95 dB and the 6-dB sensitivity roll-off is limited to 1.25 mm (24). Furthermore, because of the low efficiency of supercontinuum generation in commercial systems, the supercontinuum source needs hundreds of milliwatts to a few watts of average pump power and several tens of nanojoules pulse energy at a 1064-nm pump wavelength. Consequently, custom filters and attenuators are required to shape the output spectrum and attenuate the output power to be safely used for imaging. Recently, Yuan et al. (35) showed that excess noise can be reduced in commercial OCT systems. However, they constrain the working condition of the laser, require careful tuning of the reference arm power, and do not fundamentally solve the problem of high excess noise when using commercial optical fibers.

RESULTS

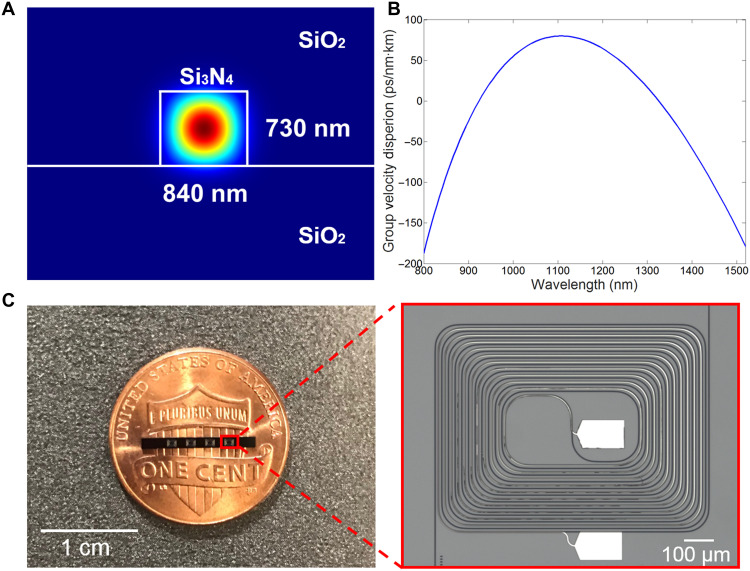

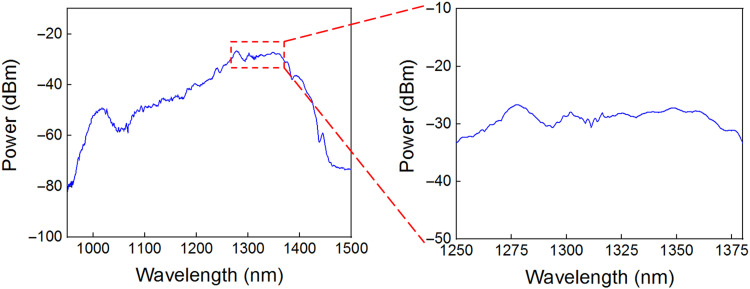

We demonstrate a supercontinuum light source for OCT imaging in a compact 1 mm by 1 mm silicon nitride (Si3N4) photonic chip. Si3N4 combines the beneficial characteristics of a high refractive index, a high nonlinear parameter, wide transparency window [from visible to mid-infrared (IR)], and compatibility with large-scale semiconductor manufacturing (36–38). Because of the high optical confinement and intrinsic nonlinearity in Si3N4, the waveguide has a nonlinearity parameter of 2710 W−1 km−1, which is 100 times larger than that of highly nonlinear fibers commonly used in commercial supercontinuum systems (39, 40), enabling power-efficient supercontinuum generation with no additional optical filtering to shape or attenuate the spectrum. The Si3N4 platform allows the dispersion to be tailored in the waveguide simply by adjusting the waveguide cross section, allowing for flexibility in the operating wavelength. This allows for power-efficient supercontinuum generation, enabling us to obtain better sensitivity and sensitivity roll-off range with a fraction of the power on the sample. We design the waveguide cross section to have a zero group velocity dispersion (GVD) point near 1300 nm (mode simulation shown in Fig. 1A and simulated GVD in Fig. 1B), enabling the generation of a spectrally flat supercontinuum spectrum for OCT. Using a 5-cm-long waveguide with a cross section of 730 × 840 nm, we achieve a broadband and spectrally flat supercontinuum spectrum with 200-fs pump pulses centered at 1300 nm with pump pulse energies of 25 pJ, which corresponds to an average pump power of 2 mW. The pump laser is commercially available, with a repetition rate of 80 MHz, and the average power is about 4 mW before coupling to the chip. The supercontinuum spectrum generated in the Si3N4 chip is using the transverse electric (TE) mode as shown in Fig. 1A and directly measured with an optical spectrum analyzer. The result is shown in Fig. 2. The spectral broadening is mainly due to self-phase modulation, resulting in a coherent low noise spectrum. The 30-dB bandwidth spans 990 to 1435 nm. The 3-dB bandwidth ranges from 1264 to 1369 nm (105 nm), corresponding to an axial resolution of 7.28 μm in air (4.86 μm in tissue). We show the numerical modeling of supercontinuum generation and calculated coherence in a Si3N4 waveguide in Materials and Methods. The fabricated waveguide only occupies an area of 1 mm2 as shown in Fig. 1C. Given these output spectral characteristics for imaging, no additional optical filtering is needed to shape or attenuate the spectrum.

Fig. 1. Simulations and microscope image of fabricated devices.

(A) Mode simulation of a 730-nm-tall and 840-nm-wide waveguide showing that the fundamental transverse electric (TE) mode is highly confined in the geometry we have chosen. (B) Simulated group velocity dispersion (GVD) of our waveguide that provides close to zero GVD near 1300 nm, which allows us to directly pump and efficiently generate broadband supercontinuum at this wavelength without any postfiltering. (C) Top view optical microscope image of multiple 5-cm-long high-confinement waveguides fabricated on the same chip. The zoom-in shows that the fabricated waveguide only occupies an area of 1 × 1 mm2. Photo credit: Xingchen Ji, Columbia University.

Fig. 2. Measured supercontinuum spectrum generated using the Si3N4 waveguide.

The spectrum has a 30-dB bandwidth of 445 nm covering 990 to 1435 nm and a flat 3-dB bandwidth spanning 1264 to 1369 nm with an input pump pulse energy of 25 pJ.

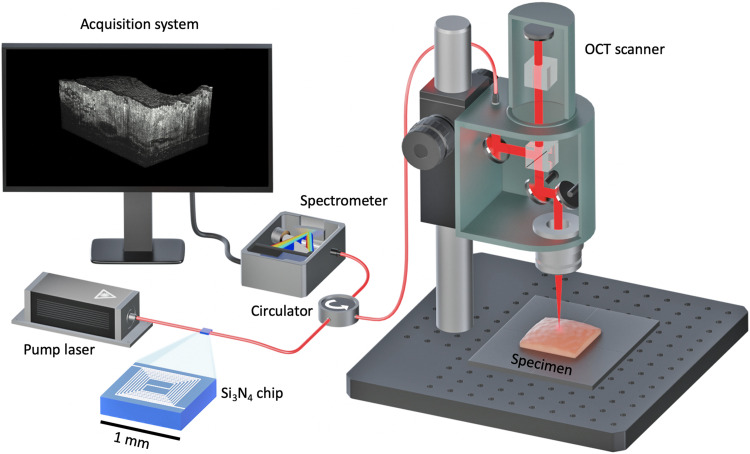

We integrate our Si3N4 chip into a fiber-coupled spectral domain (SD)–OCT system centered at 1300 nm. The schematic diagram of our system is shown in Fig. 3. The output light from our Si3N4 chip is sent directly to the OCT interferometer through a circulator. The interferometer consists of a reference arm and a sample arm. In the reference arm, a glass block is used to minimize distortion caused by dispersion. In the sample arm, a two-axis galvanometer scanner is used to scan the beam, and a telecentric scan lens (numerical aperture = 0.055 and effective focal length = 36 mm) focuses the beam onto the sample. The backscattered signals from the two interferometer arms are acquired by the spectrometer, which has 1024 pixels covering a spectral range of 1199.5 to 1367 nm and an imaging depth range of 2.52 mm.

Fig. 3. Schematic of a fiber-coupled SD OCT system with a supercontinuum source generated by the Si3N4 waveguide.

Here, we measure the performance of the Si3N4-OCT system and demonstrate 105-dB sensitivity and 1.81-mm 6-dB sensitivity roll-off with merely 300-μW power on the sample at an A-line rate of 28 kHz. For comparison, a commercial supercontinuum system shows 95 dB and 1.25-mm 6-dB sensitivity roll-off with 4 mW of power on the sample at an A-line rate of 40 kHz (SuperK Extreme) (24) and a state-of-the-art ANDi fiber–based supercontinuum SD-OCT system shows 96 dB at an A-line rate of 76 kHz and 8.8 dB/mm sensitivity roll-off with about 9 mW of power on the sample (41), respectively (see Table 1 and fig. S3). We measure the 6-dB sensitivity roll-off range to be 1.81 mm in our system, compared with the 6-dB sensitivity roll-off range of 1.25 mm using a state-of-the-art SuperK Extreme system that needs 10× more power on the sample. The sensitivity is measured using the method described previously (42). Our measured sensitivity is close to the theoretical shot noise limited prediction assuming a spectrometer detection efficiency of 0.4. The axial resolution is measured to be 7.45 μm in air (4.97 μm in tissue), which is in good agreement with the theoretical axial resolution of 7.41 μm (in air), accounting for the wavelength detection range of the spectrometer (see Materials and Methods).

Table 1. Comparison of our work with a state-of-the-art commercial supercontinuum system and an all-normal dispersion (ANDi) fiber supercontinuum system around 1300 nm.

| Pump wavelength | Repetition rate | Power on sample | Measured sensitivity |

Filter and spectral

shaping needed? |

|

|

Our work at 28-kHz

A-line rate |

1300 nm | 80 MHz | 300 μW | 105 dB | No |

|

SuperK Extreme at

40-kHz A-line rate (24) |

1064 nm | 320 MHz | 4 mW | 95 dB | Yes |

|

ANDi fiber at 76-kHz

A-line rate (41) |

1550 nm | 90 MHz | 9 mW | 96 dB | Yes |

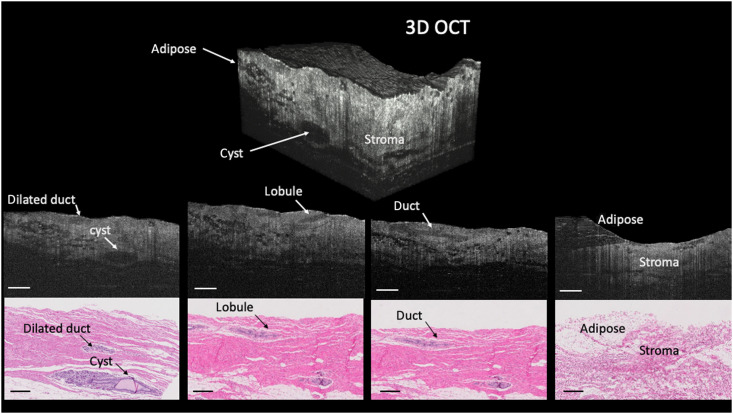

We demonstrate the ability of our Si3N4 chip-OCT system to resolve diverse microscopic biological tissue architecture by imaging healthy human breast tissue. The human breast tissue samples were collected from patients undergoing mastectomy procedures at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and were not required for diagnosis and handled in accordance with Code of Federal Regulations 45CFR46. The specimens were fixed in formalin and imaged ex vivo within 24 hours of surgical excision. Imaging was performed at an A-line rate of 28 kHz. The total acquisition time of a single image (OCT B-scan) is 35 ms and the imaging depth is 2.52 mm. Figure 4 shows a volumetric three-dimensional (3D) scan of healthy breast tissue, which demonstrates important microscopic structural features of healthy breast tissue such as milk ducts, lobules, adipose (fat), and stroma (connective tissue). We did not average or preprocess these images. We process the OCT images from the raw data by performing background subtraction, linear-k interpolation, apodization, and digital dispersion compensation. A fly-through video of the volumetric scan is shown in movie S1.

Fig. 4. Volumetric 3D scan of healthy breast parenchyma acquired with a Si3N4 chip light source.

Below, representative OCT B-scans from the 3D volume with corresponding hematoxylin and eosin histology. Visualized parenchyma structures included ducts, cysts, lobules, adipose, and stroma. Scale bars, 500 μm.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate a supercontinuum light source for OCT imaging in a compact 1 mm by 1 mm Si3N4 photonic chip that can be directly pumped at 1300 nm and does not require any optical filtering to shape or attenuate the spectrum. Our Si3N4 chip platform achieves 105-dB sensitivity and 1.81-mm 6-dB sensitivity roll-off with merely 300-μW optical power on the sample. The same sensitivity would require 100 times more optical power using a state-of-the-art commercial supercontinuum source. The central wavelength of 1300 nm used here is particularly suitable for imaging applications where deeper penetration depths are needed, such as breast cancer, cardiovascular, or dermatology research. Nevertheless, with flexible dispersion engineering enabled by integrated photonics, the source’s design can be easily modified to generate other spectral ranges, such as 1 μm or 800 nm. Silicon photonics for miniaturization of different building blocks of OCT systems has been explored recently by various groups. For example, Yurtsever et al. (43) demonstrated a silicon-based integrated interferometer that had a sensitivity of 62 dB with 115-μW power on the sample. Schneider et al. (44) realized an integrated interferometer and an integrated photodiode, which had a sensitivity of 64 dB with 300 μW power on the sample, while Eggleston et al. (45) also demonstrated an integrated interferometer with integrated balanced photodiodes and a copackaged Microelectromechanical systems mirror, which had a sensitivity of 90 dB with 550-μW power on the sample. Nguyen et al. (46) showed an integrated optics spectrometer that has a sensitivity of 75 dB, and Akca et al. (47) fabricated a miniature spectrometer and a beam splitter system, which had a sensitivity of 74 dB with 500-μW power on the sample. More recently, Rank et al. (6) demonstrated an arrayed waveguide grating, which had a sensitivity of up to 91 dB with 830-μW power on the sample.

Here, we demonstrate a miniature supercontinuum light source, which has a sensitivity of 105 dB with 300-μW power on the sample. Although we use an off-chip femtosecond pump laser in the present setup, efforts are being made toward miniaturization of mode-locked lasers (48). Together with the efforts of miniaturizing and packaging different building blocks of OCT using silicon photonics, along with the development of imaging probes (49–54), there is potential toward the realization of a high-performance, low-cost, and fully integrated OCT system.

Supercontinuum generation using integrated waveguides with different material platforms has been extensively studied over the past decade (55–70). Si3N4 has the benefit of being complementary metal-oxide semiconductor process compatible, which can leverage large-scale semiconductor manufacturing at low cost. Further, it combines the beneficial characteristics of ultralow loss (which allows fabrication of longer waveguide length and lower pump powers), a high-index contrast between the waveguide and the cladding index (which yields a large effective nonlinearity and the ability to tailor the dispersion of the waveguide), and a wide transparency window (from visible to mid-IR), which covers the wavelength windows of OCT imaging for various of applications. For example, spectra centered at 800 or 1000 nm can be generated for ophthalmic imaging, and spectra at 1700 nm or even longer wavelengths can be generated for imaging industrial materials and dental samples. These characteristics make Si3N4 a good candidate for OCT imaging applications. Unlike highly nonlinear fibers, achieving proper group-velocity dispersion requires careful engineering of the dimensions, porosity, and spacing of the interior air holes. Dispersion engineering in integrated photonics is more easily achievable, and advanced dispersion engineering techniques, such as tapering the waveguide width to shift the dispersive wave phase-matching wavelength (71), can be further applied in integrated photonics to achieve flat spectra and broader bandwidths. Our experiment demonstrates that the integrated Si3N4 photonics platform is promising for OCT imaging, and we anticipate seeing other integrated photonics platforms being used for biomedical imaging applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Si3N4 chip fabrication

We demonstrate a low-loss 5-cm-long Si3N4 waveguide in 1-mm2 area fabricated on a 4-inch silicon wafer designed for OCT imaging. Starting from the silicon wafer, we thermally grow a 4-μm-thick oxide layer as the bottom cladding. Si3N4 is deposited using low-pressure chemical vapor deposition in two steps and annealed at 1200°C in an argon atmosphere for 3 hours in between steps. After Si3N4 deposition, we deposit a SiO2 hard mask using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). We pattern our devices using electron beam lithography. Ma-N 2403 resist was used to write the pattern, and the nitride film was etched in an inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etcher using a combination of CHF3, N2, and O2 gases. After stripping the oxide mask, we anneal the devices again to remove residual N─H bonds in the Si3N4 film. We clad the devices with 500 nm of high-temperature silicon dioxide deposited at 800°C, followed by 2 μm of SiO2 using PECVD. A deep-etched facet and an inverse taper are designed and used to minimize the edge coupling loss.

Nonlinearity calculation

The nonlinear coefficient γ is often used to determine the degree of nonlinearity and is given by Eq. 1 (72)

| (1) |

where n2 is the nonlinear Kerr coefficient of the material, λ is the wavelength, and Aeff is the effective mode area. The n2 of Si3N4 is 2.45 × 10−15 cm2/W, which is 10 times larger than that of silica (73). The Aeff of our waveguide is calculated to be 0.43 μm2. The small Aeff and large n2 of Si3N4 leads to the nonlinearity parameter γ value of 2710 W−1 km−1, which is more than 100 times that of high nonlinear fibers and more than 1000 times that of standard single-mode fibers (40).

Resolution, sensitivity, and sensitivity roll-off

The axial resolution of our chip-based supercontinuum source is 7.45 μm in air (4.97 μm in tissue). We measured the axial resolution by calculating the full-width half-maximum (FWHM) of the axial point spread function (PSF) of a flat mirror at the focal plane of the sample arm (fig.S1). Our measurement is in good agreement with the theoretical axial resolution of 7.41 μm (in air), accounting for the wavelength detection range of the spectrometer using Eq. 2

| (2) |

where λ0 is the central wavelength and ΔλFWHM is the FWHM of the spectrum.

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), used interchangeably with sensitivity in the literature, is directly proportional to the power reflected by the sample divided by the noise of the system (Eq. 3) (74). The noise of the system is defined as , where represents the excess noise, represents the shot noise, and represents the receiver noise. The receiver noise term, which represents the sum of the dark noise of the detector and readout noise of the circuit, is negligible in comparison to the other terms and thus omitted from Eq. 3

| (3) |

Combining the supercontinuum generated by our Si3N4 chip with a fiber-based SD-OCT system, we achieve 105-dB sensitivity. The measured sensitivity is in agreement with the theoretical shot noise limited prediction assuming a spectrometer detection efficiency of 0.4.

In SD-OCT, specifically, the sensitivity decreases along the imaging depth. There is a reduction in fringe visibility that is more predominant at higher fringe frequencies due to the finite resolution of the spectrometer. The standard method of characterizing the sensitivity fall-off is by measuring the depth at which the signal decreases by 6 dB. Here, we measure the sensitivity fall-off by placing a flat mirror at the focal plane of the sample arm while moving the reference arm mirror at fixed increments and measuring the PSF at each position until a 6-dB sensitivity fall-off is observed. We measured 1.81-mm 6-dB sensitivity roll-off with 300-μW power on the sample at an A-line rate of 28 kHz (fig. S2). We observed noticeably stronger sensitivity fall-off performance for our chip-based supercontinuum source when compared to commercial supercontinuum sources (fig. S3).

Numerical modeling of supercontinuum generation in the Si3N4 waveguide

We have performed numerical modeling of the pulse propagation dynamics in a silicon nitride (Si3N4) waveguide using parameters similar to our experiment. The dispersion of the waveguide is simulated using a finite-element mode solver. The waveguide cross section is 730 × 840 nm. We model pulse propagation in a 5-cm-long waveguide by solving the nonlinear Schrödinger’s equation using the split-step Fourier method (75), taking into account higher-order dispersion, third-order nonlinearity, and self-steepening. The input pulse has a 200-fs duration centered at 1300 nm with a pulse energy of 25 pJ. The simulated spectrum spans 500 nm. Discrepancies in the spectral profile between the experiment and simulation are attributed to the difference in the simulated dispersion from the actual waveguide dispersion due to fabrication tolerances. In addition, we analyze the spectral coherence of the generated output by performing 128 independent simulations using pulses seeded with quantum shot noise and calculating the first-order mutual coherence g12 (75–77). Figure S4 shows the simulated spectrum and the calculated coherence. Our results indicate that the spectrum exhibits near-unity spectral coherence over the entire spectral bandwidth. We have also shown that it is possible to pump at 1.06 μm and generated a broadband highly spectrally coherent supercontinuum covering the OCT imaging window of 1300 nm with dispersion engineering in fig. S5.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Hibshoosh for assistance in reviewing the H&E histology slides and M. Marshall for artistic help with a figure. We thank J. Rocha Rodrigues and A. Mohanty for helpful discussions. Funding: This work was performed in part at the Cornell NanoScale Facility, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI), which is supported by the NSF (grant NNCI-2025233). We acknowledge support from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-15-1-0303) and the NIH (4DP2HL127776-02). Author contributions: X.J. and D.M. contributed equally to this work. X.J. and D.M. prepared the manuscript in discussion with all authors. X.J. designed and fabricated the silicon nitride devices. Y.O. performed modeling and supercontinuum generation. X.J., D.M., and Y.O. performed the experiments. D.M. set up the OCT system. X.J. and D.M. analyzed the data together. M.L., C.P.H., and A.L.G. supervised the project. Competing interests: All authors are inventors on a patent application related to this work filed by Columbia University (no. CU21083–101879.000129). The authors declare no other competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S5

Legend for movie S1

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movie S1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Huang D., Swanson E. A., Lin C. P., Schuman J. S., Stinson W. G., Chang W., Hee M. R., Flotte T., Gregory K., Puliafito C. A., Fujimoto J. G., Optical coherence tomography. Science 254, 1178–1181 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hee M. R., Izatt J. A., Swanson E. A., Huang D., Schuman J. S., Lin C. P., Puliafito C. A., Fujimoto J. G., Optical coherence tomography of the human retina. Arch. Ophthalmol. 113, 325–332 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drexler W., Morgner U., Ghanta R. K., Kärtner F. X., Schuman J. S., Fujimoto J. G., Ultrahigh-resolution ophthalmic optical coherence tomography. Nat. Med. 7, 502–507 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yi J., Wei Q., Liu W., Backman V., Zhang H. F., Visible-light optical coherence tomography for retinal oximetry. Opt. Lett. 38, 1796–1798 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chopra R., Wagner S. K., Keane P. A., Optical coherence tomography in the 2020s—Outside the eye clinic. Eye 35, 236–243 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rank E. A., Sentosa R., Harper D. J., Salas M., Gaugutz A., Seyringer D., Nevlacsil S., Maese-Novo A., Eggeling M., Muellner P., Hainberger R., Sagmeister M., Kraft J., Leitgeb R. A., Drexler W., Toward optical coherence tomography on a chip: In vivo three-dimensional human retinal imaging using photonic integrated circuit-based arrayed waveguide gratings. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao T., Tey H. L., High-definition optical coherence tomography—An aid to clinical practice and research in dermatology. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 13, 886–890 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robles F. E., Zhou K. C., Fischer M. C., Warren W. S., Stimulated Raman scattering spectroscopic optical coherence tomography. Optica 4, 243–246 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welzel J., Optical coherence tomography in dermatology: A review. Skin Res. Technol. 7, 1–9 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suter M. J., Vakoc B. J., Yachimski P. S., Shishkov M., Lauwers G. Y., Mino-Kenudson M., Bouma B. E., Nishioka N. S., Tearney G. J., Comprehensive microscopy of the esophagus in human patients with optical frequency domain imaging. Gastrointest. Endosc. 68, 745–753 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gora M. J., Sauk J. S., Carruth R. W., Gallagher K. A., Suter M. J., Nishioka N. S., Kava L. E., Rosenberg M., Bouma B. E., Tearney G. J., Tethered capsule endomicroscopy enables less invasive imaging of gastrointestinal tract microstructure. Nat. Med. 19, 238–240 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li K., Liang W., Mavadia-Shukla J., Park H.-C., Li D., Yuan W., Wan S., Li X., Super-achromatic optical coherence tomography capsule for ultrahigh-resolution imaging of esophagus. J. Biophotonics 12, e201800205 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen F. T., Zysk A. M., Chaney E. J., Kotynek J. G., Oliphant U. J., Bellafiore F. J., Rowland K. M., Johnson P. A., Boppart S. A., Intraoperative evaluation of breast tumor margins with optical coherence tomography. Cancer Res. 69, 8790–8796 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy K. M., Zilkens R., Allen W. M., Foo K. Y., Fang Q., Chin L., Sanderson R. W., Anstie J., Wijesinghe P., Curatolo A., Tan H. E. I., Morin N., Kunjuraman B., Yeomans C., Chin S. L., DeJong H., Giles K., Dessauvagie B. F., Latham B., Saunders C. M., Kennedy B. F., Diagnostic accuracy of quantitative micro-elastography for margin assessment in breast-conserving surgery. Cancer Res. 80, 1773–1783 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mojahed D., Ha R. S., Chang P., Gan Y., Yao X., Angelini B., Hibshoosh H., Taback B., Hendon C. P., Fully automated postlumpectomy breast margin assessment utilizing convolutional neural network based optical coherence tomography image classification method. Acad. Radiol. 27, e81–e86 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Froehly L., Meteau J., Supercontinuum sources in optical coherence tomography: A state of the art and the application to scan-free time domain correlation techniques and depth dependant dispersion compensation. Opt. Fiber Technol. 18, 411–419 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bizheva K., Tan B., MacLelan B., Kralj O., Hajialamdari M., Hileeto D., Sorbara L., Sub-micrometer axial resolution OCT for in-vivo imaging of the cellular structure of healthy and keratoconic human corneas. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 800–812 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drexler W., Ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. J. Biomed. Opt. 9, 47–74 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartl I., Li X. D., Chudoba C., Ghanta R. K., Ko T. H., Fujimoto J. G., Ranka J. K., Windeler R. S., Ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography using continuum generation in an air–silica microstructure optical fiber. Opt. Lett. 26, 608–610 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishizawa N., Kawagoe H., Yamanaka M., Matsushima M., Mori K., Kawabe T., Wavelength dependence of ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography using supercontinuum for biomedical imaging. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 25, 7101115 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang T.-A., Chan M.-C., Lee H.-C., Lee C.-Y., Tsai M.-T., Ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography/angiography with an economic and compact supercontinuum laser. Biomed. Opt. Express 10, 5687–5702 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng X., Zhang X., Li C., Wang X., Jerwick J., Xu T., Ning Y., Wang Y., Zhang L., Zhang Z., Ma Y., Zhou C., Ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence microscopy accurately classifies precancerous and cancerous human cervix free of labeling. Theranostics 8, 3099–3110 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.You Y.-J., Wang C., Lin Y.-L., Zaytsev A., Xue P., Pan C.-L., Ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography at 1.3 μm central wavelength by using a supercontinuum source pumped by noise-like pulses. Laser Phys. Lett. 13, 025101 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 24.M. Maria, M. Bondu, R. D. Engelsholm, T. Feuchter, P. M. Moselund, L. Leick, O. Bang, A. Podoleanu, A comparative study of noise in supercontinuum light sources for ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography, in Proceedings of SPIE (San Francisco, California, United States, 2017), vol. 10056. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maria M., Gonzalo I. B., Feuchter T., Denninger M., Moselund P. M., Leick L., Bang O., Podoleanu A., Q-switch-pumped supercontinuum for ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lett. 42, 4744–4747 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen M., Gonzalo I. B., Engelsholm R. D., Maria M., Israelsen N. M., Podoleanu A., Bang O., Noise of supercontinuum sources in spectral domain optical coherence tomography. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 36, A154–A160 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao X., Gan Y., Marboe C. C., Hendon C. P., Myocardial imaging using ultrahigh-resolution spectral domain optical coherence tomography. J. Biomed. Opt. 21, 061006 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsiung P.-L., Chen Y., Ko T. H., Fujimoto J. G., de Matos C. J. S., Popov S. V., Taylor J. R., Gapontsev V. P., Optical coherence tomography using a continuous-wave, high-power, Raman continuum light source. Opt. Express 12, 5287–5295 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bizheva K., Pflug R., Hermann B., Považay B., Sattmann H., Qiu P., Anger E., Reitsamer H., Popov S., Taylor J. R., Unterhuber A., Ahnelt P., Drexler W., Optophysiology: Depth-resolved probing of retinal physiology with functional ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 5066–5071 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishida S., Nishizawa N., Quantitative comparison of contrast and imaging depth of ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography images in 800–1700 nm wavelength region. Biomed. Opt. Express 3, 282–294 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aguirre A., Nishizawa N., Fujimoto J., Seitz W., Lederer M., Kopf D., Continuum generation in a novel photonic crystal fiber for ultrahigh resolution optical coherence tomography at 800 nm and 1300 nm. Opt. Express 14, 1145–1160 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spöler F., Kray S., Grychtol P., Hermes B., Bornemann J., Först M., Kurz H., Simultaneous dual-band ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography. Opt. Express 15, 10832–10841 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heidt A. M., Feehan J. S., Price J. H. V., Feurer T., Limits of coherent supercontinuum generation in normal dispersion fibers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 34, 764–775 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidt A. M., Hartung A., Bosman G. W., Krok P., Rohwer E. G., Schwoerer H., Bartelt H., Coherent octave spanning near-infrared and visible supercontinuum generation in all-normal dispersion photonic crystal fibers. Opt. Express 19, 3775–3787 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan W., Mavadia-Shukla J., Xi J., Liang W., Yu X., Yu S., Li X., Optimal operational conditions for supercontinuum-based ultrahigh-resolution endoscopic OCT imaging. Opt. Lett. 41, 250–253 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moss D. J., Morandotti R., Gaeta A. L., Lipson M., New CMOS-compatible platforms based on silicon nitride and Hydex for nonlinear optics. Nat. Photonics 7, 597–607 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goykhman I., Desiatov B., Levy U., Ultrathin silicon nitride microring resonator for biophotonic applications at 970 nm wavelength. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 081108 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilmart Q., El Dirani H., Tyler N., Fowler D., Malhouitre S., Garcia S., Casale M., Kerdiles S., Hassan K., Monat C., Letartre X., Kamel A., Pu M., Yvind K., Oxenløwe L., Rabaud W., Sciancalepore C., Szelag B., Olivier S., A versatile silicon-silicon nitride photonics platform for enhanced functionalities and applications. Appl. Sci. 9, 255 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okawachi Y., Yu M., Cardenas J., Ji X., Lipson M., Gaeta A. L., Coherent, directional supercontinuum generation. Opt. Lett. 42, 4466–4469 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto Y., Tamura Y., Hasegawa T., Silica-based highly nonlinear fibers and their applications. SEI Tech. Rev. 83, 15–20 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 41.S S. R. D., Jensen M., Grüner-Nielsen L., Olsen J. T., Heiduschka P., Kemper B., Schnekenburger J., Glud M., Mogensen M., Israelsen N. M., Bang O., Shot-noise limited, supercontinuum based optical coherence tomography. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 133 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cimalla P., Walther J., Mehner M., Cuevas M., Koch E., Simultaneous dual-band optical coherence tomography in the spectral domain for high resolution in vivo imaging. Opt. Express 17, 19486–19500 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yurtsever G., Weiss N., Kalkman J., van Leeuwen T. G., Baets R., Ultra-compact silicon photonic integrated interferometer for swept-source optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lett. 39, 5228–5231 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneider S., Lauermann M., Dietrich P.-I., Weimann C., Freude W., Koos C., Optical coherence tomography system mass-producible on a silicon photonic chip. Opt. Express 24, 1573–1586 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.M. S. Eggleston, F. Pardo, C. Bolle, B. Farah, N. Fontaine, H. Safar, M. Cappuzzo, C. Pollock, D. J. Bishop, M. P. Earnshaw, 90dB sensitivity in a chip-scale swept-source optical coherence tomography system, in Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (2018) (Optical Society of America, 2018), paper JTh5C.8. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen V. D., Akca B. I., Wörhoff K., de Ridder R. M., Pollnau M., van Leeuwen T. G., Kalkman J., Spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging with an integrated optics spectrometer. Opt. Lett. 36, 1293–1295 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akca B. I., Považay B., Alex A., Wörhoff K., de Ridder R. M., Drexler W., Pollnau M., Miniature spectrometer and beam splitter for an optical coherence tomography on a silicon chip. Opt. Express 21, 16648–16656 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kemiche M., Lhuillier J., Callard S., Monat C., Design optimization of a compact photonic crystal microcavity based on slow light and dispersion engineering for the miniaturization of integrated mode-locked lasers. AIP Adv. 8, 015211 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X., Chudoba C., Ko T., Pitris C., Fujimoto J. G., Imaging needle for optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lett. 25, 1520–1522 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu Y., Xi J., Huo L., Padvorac J., Shin E. J., Giday S. A., Lennon A. M., Canto M. I. F., Hwang J. H., Li X., Robust high-resolution fine OCT needle for side-viewing interstitial tissue imaging. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 16, 863–869 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gora M. J., Suter M. J., Tearney G. J., Li X., Endoscopic optical coherence tomography: Technologies and clinical applications [Invited]. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 2405–2444 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan W., Brown R., Mitzner W., Yarmus L., Li X., Super-achromatic monolithic microprobe for ultrahigh-resolution endoscopic optical coherence tomography at 800 nm. Nat. Commun. 8, 1531 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cui D., Chu K. K., Yin B., Ford T. N., Hyun C., Leung H. M., Gardecki J. A., Solomon G. M., Birket S. E., Liu L., Rowe S. M., Tearney G. J., Flexible, high-resolution micro-optical coherence tomography endobronchial probe toward in vivo imaging of cilia. Opt. Lett. 42, 867–870 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim S., Crose M., Eldridge W. J., Cox B., Brown W. J., Wax A., Design and implementation of a low-cost, portable OCT system. Biomed. Opt. Express 9, 1232–1243 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh N., Xin M., Vermeulen D., Shtyrkova K., Li N., Callahan P. T., Magden E. S., Ruocco A., Fahrenkopf N., Baiocco C., Kuo B. P.-P., Radic S., Ippen E., Kärtner F. X., Watts M. R., Octave-spanning coherent supercontinuum generation in silicon on insulator from 1.06 μm to beyond 2.4 μm. Light Sci. Appl. 7, 17131 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiles J., Nader N., Hickstein D. D., Yu S. P., Briles T. C., Carlson D., Jung H., Shainline J. M., Diddams S., Papp S. B., Nam S. W., Mirin R. P., Deuterated silicon nitride photonic devices for broadband optical frequency comb generation. Opt. Lett. 43, 1527–1530 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duchesne D., Peccianti M., Lamont M. R. E., Ferrera M., Razzari L., Légaré F., Morandotti R., Chu S., Little B. E., Moss D. J., Supercontinuum generation in a high index doped silica glass spiral waveguide. Opt. Express 18, 923–930 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuyken B., Liu X., Osgood R. M. Jr., Baets R., Roelkens G., Green W. M. J., Mid-infrared to telecom-band supercontinuum generation in highly nonlinear silicon-on-insulator wire waveguides. Opt. Express 19, 20172–20181 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halir R., Okawachi Y., Levy J. S., Foster M. A., Lipson M., Gaeta A. L., Ultrabroadband supercontinuum generation in a CMOS-compatible platform. Opt. Lett. 37, 1685–1687 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leo F., Gorza S.-P., Coen S., Kuyken B., Roelkens G., Coherent supercontinuum generation in a silicon photonic wire in the telecommunication wavelength range. Opt. Lett. 40, 123–126 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Epping J. P., Hellwig T., Hoekman M., Mateman R., Leinse A., Heideman R. G., van Rees A., van der Slot P. J. M., Lee C. J., Fallnich C., Boller K.-J., On-chip visible-to-infrared supercontinuum generation with more than 495 THz spectral bandwidth. Opt. Express 23, 19596–19604 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuyken B., Ideguchi T., Holzner S., Yan M., Hänsch T. W., Van Campenhout J., Verheyen P., Coen S., Leo F., Baets R., Roelkens G., Picqué N., An octave-spanning mid-infrared frequency comb generated in a silicon nanophotonic wire waveguide. Nat. Commun. 6, 6310 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh N., Hudson D. D., Yu Y., Grillet C., Jackson S. D., Casas-Bedoya A., Read A., Atanackovic P., Duvall S. G., Palomba S., Luther-Davies B., Madden S., Moss D. J., Eggleton B. J., Midinfrared supercontinuum generation from 2 to 6 μm in a silicon nanowire. Optica 2, 797–802 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klenner A., Mayer A. S., Johnson A. R., Luke K., Lamont M. R. E., Okawachi Y., Lipson M., Gaeta A. L., Keller U., Gigahertz frequency comb offset stabilization based on supercontinuum generation in silicon nitride waveguides. Opt. Express 24, 11043–11053 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu X., Pu M., Zhou B., Krückel C. J., Fülöp A., Torres-Company V., Bache M., Octave-spanning supercontinuum generation in a silicon-rich nitride waveguide. Opt. Lett. 41, 2719–2722 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Porcel M. A. G., Schepers F., Epping J. P., Hellwig T., Hoekman M., Heideman R. G., van der Slot P. J. M., Lee C. J., Schmidt R., Bratschitsch R., Fallnich C., Boller K.-J., Two-octave spanning supercontinuum generation in stoichiometric silicon nitride waveguides pumped at telecom wavelengths. Opt. Express 25, 1542–1554 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sinobad M., Monat C., Luther-davies B., Ma P., Madden S., Moss D. J., Mitchell A., Allioux D., Orobtchouk R., Boutami S., Hartmann J.-M., Fedeli J.-M., Grillet C., Mid-infrared octave spanning supercontinuum generation to 8.5 μm in silicon-germanium waveguides. Optica 5, 360–366 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu M., Desiatov B., Okawachi Y., Gaeta A. L., Lončar M., Coherent two-octave-spanning supercontinuum generation in lithium-niobate waveguides. Opt. Lett. 44, 1222–1225 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuyken B., Billet M., Leo F., Yvind K., Pu M., Octave-spanning coherent supercontinuum generation in an AlGaAs-on-insulator waveguide. Opt. Lett. 45, 603–606 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lu J., Liu X., Bruch A. W., Zhang L., Wang J., Yan J., Tang H. X., Ultraviolet to mid-infrared supercontinuum generation in single-crystalline aluminum nitride waveguides. Opt. Lett. 45, 4499–4502 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh N., Vermulen D., Ruocco A., Li N., Li N., Ippen E., Kärtner F. X., Watts M. R., Supercontinuum generation in varying dispersion and birefringent silicon waveguide. Opt. Express 27, 31698–31712 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.G. Agrawal, Optics and photonics, in Nonlinear Fiber Optics (Fifth Edition) (Academic Press, 2013), pp. 457–496. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ikeda K., Saperstein R. E., Alic N., Fainman Y., Thermal and Kerr nonlinear properties of plasma-deposited silicon nitride/silicon dioxide waveguides. Opt. Express 16, 12987–12994 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leitgeb R., Hitzenberger C., Fercher A., Performance of fourier domain vs time domain optical coherence tomography. Opt. Express 11, 889–894 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnson A. R., Mayer A. S., Klenner A., Luke K., Lamb E. S., Lamont M. R. E., Joshi C., Okawachi Y., Wise F. W., Lipson M., Keller U., Gaeta A. L., Octave-spanning coherent supercontinuum generation in a silicon nitride waveguide. Opt. Lett. 40, 5117–5120 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gu X., Kimmel M., Shreenath A. P., Trebino R., Dudley J. M., Coen S., Windeler R. S., Experimental studies of the coherence of microstructure-fiber supercontinuum. Opt. Express 11, 2697–2703 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ruehl A., Martin M. J., Cossel K. C., Chen L., McKay H., Thomas B., Benko C., Dong L., Dudley J. M., Fermann M. E., Hartl I., Ye J., Ultrabroadband coherent supercontinuum frequency comb. Phys. Rev. A 84, 011806 (2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S5

Legend for movie S1

Movie S1