Abstract

Little is known about the impact of engagement in personally meaningful activities for older adults. Thus, this study examines the impact of engagement in one’s favorite activity on cognitive, emotional, functional, and health-related outcomes in older adults with and without cognitive impairment. Data were obtained from 1,397 persons living with dementia (PLWD) and 4,719 cognitively healthy persons (CHP) who participated in wave 2 of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). Sociodemographic characteristics were examined by cognitive status. A multivariate analysis of variance indicated that, for PLWD, engagement in favorite activity was associated with greater functional independence and decreased depression. For CHP, engagement in favorite activity was associated with greater functional independence, decreased depression and anxiety, and better performance on memory measures. Findings suggest that engagement in valued activities that are considered personally meaningful may have significant and distinct benefits for persons with and without dementia.

Keywords: successful aging, memory, mental health, dementia, National Health and Aging Trends Study

Introduction

Engagement in meaningful activity is a critical component of successful aging, and evidence-based benefits include maintenance or improvement of cognitive, physical, social, and psychological function of older adults (Carlson et al., 2015; Fried et al., 2004) with and without cognitive impairment. In cognitively healthy older adults, activity engagement can serve as a protective buffer from age-related physical and cognitive decline (Haslam, Cruwys, Milne, Kan, & Haslam, 2015; James et al., 2011; Kuiper et al., 2015) and can improve well-being (Adams et al., 2011). For persons living with dementia (PLWD), research has shown that activity decreases depressive symptomatology, improves performance of daily activities, improves overall health, improves quality of life, fosters positive attitudes toward caregivers, and decreases challenging behaviors (Barton, Ketelle, Merrilees, & Miller, 2016; Blesedell, Cohn, & Boyt, 2003; Vikström, Josephsson, Stigsdotter-Neely, & Nygård, 2008; Gitlin et al., 2018; 2010). Of note, even persons with severe dementia are capable of being engaged in meaningful activity (Regier, Hodgson, & Gitlin, 2017; Gitlin et al., 2010;2018) as well as expressing needs, desires, and choices related to activity selection (Tomori et al., 2015).

The need to seek out meaningful activity appears to be part of human nature (Blesedell et al., 2003; Hasselkus, 2002; Lawton, 2001). Research shows that older adults continue to desire meaningful activity irrespective of cognitive status, though a higher percentage of cognitively healthy persons (CHP) attribute greater importance to activities than individuals with possible or probable dementia (Parisi et al., 2017). It is clear that activity of any kind is beneficial to older adults, but less is known regarding how the value ascribed to an activity affects these benefits. Indeed, a critical review of the relationship between activity and well-being in late-life found that very few studies assessed the underlying purpose or meaning of activities (Adams, Leibbrandt, & Moon, 2011). In the context of dementia, “meaningful activity” is defined as that which enables a person to remain involved in everyday activities and personal relationships (Phinney, 2006). The conceptualization of an activity as personally meaningful, however, is subjective (Ikiugu, 2018), regardless of cognitive status, and depends on myriad factors such as preferences, personality, circumstances, and past experiences related to that activity (Eakman & Eklund, 2012; Persson, Erlandsson, Eklund, & Iwarsson, 2001).

In recent years, researchers have recognized a relationship between participation in personally meaningful activities and measures of well-being (Adams et al., 2011; Eakman, 2011; Eakman, Carlson, & Clark, 2010a;2010b; Hasselkus, 2002; Hooker, Masters, Vagnini, & Rush, 2020; Thomson, 2003). For example, the purpose and/or meaning of an activity mediates the relationship between activity participation and well-being in cognitively healthy older adults (Adams et al., 2011). For PLWD, research suggests that engagement in activities that are personally meaningful to them may increase well-being (Menne, Johnson, Whitlatch, & Schwartz, 2012; Phinney, Chaudhury, & O’Connor, 2007). While engagement in any activity is better than nothing (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2010), activities that are intrinsically valued and personally meaningful are more strongly correlated with self-rated health or life satisfaction (Cantor & Sanderson, 1999; Eakman et al., 2010). One possible explanation for this finding is that the meaning derived from an activity imbues one’s overall life with meaning, which impacts physical and mental health. Furthermore, engagement in personally meaningful activity may contribute to a sense of purpose, which can enhance well-being (Mee & Sumsion, 2001).

The personal meaning of an activity may also impact whether or not engagement occurs at all. Indeed, a recent study found the meaning ascribed to an activity to be the strongest predictor of engagement in a sample of older adults (Adenji & Hong, 2019). While other factors associated with activity engagement such as disability, pain, and environment are well-researched, the predictive value of personal meaning is less well-known.

Two relevant theoretical models of adult development suggest that the value attributed to an activity may have significant implications for successful aging, health, and one’s sense of purpose and fulfillment in life. The selective optimization with compensation model of aging (SOC; Baltes & Baltes, 1990) posits that, as persons age and both internal and external resources decline, they prioritize (select) goals, making optimal use of preserved capabilities and available resources while finding ways to compensate for any limitations, potentially as a means for continuing participation in activities that are most personally relevant. Within a related framework, continuity theory (Atchley, 1989; 1999; 2003), individuals strive to maintain a personally meaningful lifestyle by engaging in activities that further value-based goals. Continuity theory and SOC highlight the presumed benefits of selecting and investing in valued activities as they relate to health and life satisfaction. Furthermore, these theories align with other social science frameworks detailing how the meaning ascribed to our daily activities contributes to life satisfaction and sense of purpose (Eakman et al., 2010).

Despite the substantial literature highlighting the overall benefits of activity engagement throughout the life course, few studies have examined the distinct impact of personally meaningful activities for older adults. The literature examining whether activities that are personally meaningful and valued have benefits for persons with and without dementia beyond those associated with general activity engagement is particularly scarce. Consequently, this study aims to explore this under-researched component of activity engagement, vis-à-vis the cognitive, emotional, functional, and health-related consequences of valued activity engagement (or lack thereof) in older adults with and without cognitive impairment.

Methods

This study utilized data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), a large, nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older (N = 8,245). Further details regarding study design are described elsewhere (e.g., Montaquila, Freedman, Edwards, & Kasper, 2012). Briefly, the NHATS collects detailed information on participants’ physical and cognitive capacity, the extent of participation in daily activities, living arrangements, economic status, and well-being. To date, nine waves of data have been collected. Starting in Wave 2, a question was added to measure favorite activity. For purposes of the current analyses, data from Wave 2 was utilized.

The NHATS sampling frame includes all persons enrolled in Medicare, representing 96% of the U.S. Medicare population. The sampling frame excluded the 4% of older adults not eligible for Medicare for various reasons (Kasper & Freedman, 2014). Specific cases were selected for the first wave of NHATS using a stratified, three-stage design, which selected counties or groups of counties from the contiguous United States, ZIP codes, and Medicare beneficiaries enrolled as of September 30, 2010 (Kasper & Freedman, 2014). NHATS data is accessible to the public via an online repository.

Sample

The NHATS administers assessment batteries to participants on an annual basis. Participants in the current sample were 6,116 persons assessed at the end of the second year of the study. Respondents were classified as having probable or possible dementia (n=1,397) or no dementia (n=4,719) according to the NHATS dementia classification scheme described below (under Measures; Kasper, Freedman, & Spillman, 2013).

Proxy respondents completed the second-year interview for 70 CHP and 348 participants with dementia. The 70 proxies of CHP were primarily children (42.9%) or a spouse/partner (30%), followed by “other” relative (17.1%) and non-relative (10%). Nearly 73% of proxies were female, and 31.4% lived with the study participant. The 348 proxies of PLWD were primarily children (54%), followed by spouses/partners (20.4%), “other” relatives (18.1%), and non-relatives (7.5%). More than 77% of proxies were female, and 42% lived with the study participant with dementia.

Measures

Dementia status.

As noted above, a classification scheme was devised for NHATS (Kasper et al., 2013). In brief, probable dementia was defined as being diagnosed with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease by a physician (as reported by the participant or proxy) or demonstrating impairment (defined as scores ≤1.5 SDs from the mean) in at least two of three assessed AD8 (Galvin et al., 2005) cognitive domains of memory, orientation, and executive function. Possible dementia was indicated by impairment in at least one cognitive domain (Kasper et al., 2013).

Cognition.

Executive function was assessed using the Clock Drawing Test (Wolf-Klein et al., 1998), and memory (immediate and delayed recall) was measured by a word-list memory test (Morris et al., 1989). In the Clock Drawing Test, participants were given a sheet of paper with a large circle on it and were instructed to draw a complete picture of a clock face within the circle, with the hands of the clock pointing to “10 after 11.” Participants were given two minutes to complete the drawing. Clocks were rated according to standard criteria (0=unrecognizable as a clock to 5=accurate depiction), with higher scores representing more complete and accurate drawings (Schretlen et al., 2010).

The word-list memory test comprised ten words, and participants were asked to recall the words immediately after presentation of the list, and again after a delay of approximately five minutes. Results provide scores for both immediate and delayed recall.

Engagement.

NHATS participants or, if necessary, their proxies, were asked several questions regarding activity engagement and preferences. The particular activity deemed his or her “favorite” was identified and recorded. Engagement in one’s favorite activity was assessed through the following question: “Since the time of the last interview [one year ago], have you done [your favorite activity]?” Participants (or proxies speaking on their behalf) responded ‘yes’ or ‘no.’

Type of activity.

Study participants were asked to identify a favorite activity. Responses were grouped into 10 categories by an NHATS panel: 1) self-care, 2) productive activities, 3) shopping, 4) household activities, 5) care of others, 6) socializing, 7) non-active leisure, 8) active leisure, 9) religious and organizational activities, and 10) other/miscellaneous. Specific responses that fall under each category can be seen in a supplemental document (Supplemental Table 1).

Mental health.

Anxiety symptoms were measured via the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2), a two-question screening tool for GAD and other anxiety disorders (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan, & Löwe, 2006). The two questions were as follows: “Over the last month, how often have you 1) felt nervous, anxious, or on edge; and 2) been unable to stop or control worrying?” (Note that the non-NHATS GAD-2 measures symptoms over the past two weeks.) Responses were recoded to correspond with the 4-point Likert scale of the GAD-2, where 0 = “not at all,” 1 = “several days,” 2 = “more than half the days,” and 3 = “nearly every day.” Total scores ranged from 0 to 6, with scores greater than or equal to 3 having a sensitivity of .76 and specificity of .81 for identifying any anxiety disorder (Plummer, Manea, Trepel, & McMillan, 2016).

Depressed mood and anhedonia were assessed via the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), a two-question screener for depressive symptoms (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2003). The two questions were as follows: “Over the last month, how often have you 1) had little interest or pleasure in doing things; and 2) felt down, depressed, or hopeless?” (Note that the non-NHATS PHQ-2 measures symptoms over the past two weeks). Responses were recoded to correspond with the 4-point Likert scale of the PHQ-2, where 0=not at all, 1=several days, 2=more than half the days, and 3=nearly every day. Total scores ranged from 0 to 6, with a cutoff score of 3 as the optimal cut point for screening purposes (Kroenke et al., 2003). Both the GAD-2 and PHQ-2 are standardized and validated measures for use in both clinical and older populations.

Functional status.

From the NHATS data, we derived a measure of basic self-care activities, informed by the Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963), and a measure of more complex household activities, informed by the Lawton-Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) Scale (Lawton & Brody, 1969). The derived ADL scale (Supplemental Table 2) examined how often in the past month participants received help with any of the following basic activities of daily living: eating, transferring/ambulating, dressing, bathing, or toileting (1=impaired/received assistance, 0=did not receive assistance). The derived IADL questions (Supplemental Table 3) asked how often in the past month participants received help with any of the following instrumental daily activities: cooking, doing laundry, shopping, managing finances, managing medications, and driving (1=impaired/received assistance, 0=did not receive assistance). We constructed a summary functional limitation score as the sum of the ADL and IADL variables (range 0–11; higher number indicates greater disabilities). This procedure has previously been described and used in studies of disability in older adults (Spector & Fleishman, 1998).

Health.

A count of total number of chronic health conditions (range: 0–11) was computed based on participant history of the following conditions: heart attack, heart disease, high blood pressure, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, dementia, and cancer.

Analysis

Sociodemographic characteristics were examined by cognitive status. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to evaluate whether favorite activity engagement led to differences between persons with and without dementia on an interpretable composite of cognitive, emotional, functional, and health-related variables. A significant Wilks’ lambda effect was followed by univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to identify which measures contributed to the significant multivariate effect. Bivariate correlations of relevant characteristics that were not suitable for MANOVA were measured with the Pearson Product-Moments two-tailed correlation coefficient analysis. All statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25.

Results

Sample Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, PLWD were predominantly female (60.1%), Caucasian (65.2%), widowed (49.7%), resided alone (34.6%) in the community (59.8%), and had a mean age of 82.0 years (SD=7.74). Cognitively healthy participants were primarily female (57.8%), Caucasian (75.9%), married (52.7%), resided with their spouse (42.4%) in the community (79.3%), and had a mean age of 76.0 years (SD=7.21). Analysis of between-groups differences revealed that CHP were more likely to be younger, Caucasian, married/partnered, and live with their spouse than persons with probable or possible dementia (p< .001 for all; Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and functional characteristics of persons with dementia vs. those without

| Characteristics | Full Sample n = 6,116 |

Dementia n = 1,397 |

No Dementia n = 4,406 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 77.7 (7.91) (R=65–106) |

81.9 (7.72) (R = 65–106) |

76.0 (7.21) (R = 65–102) |

.000 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 41.9 | 40.4 | 42.2 | .242 |

| Female | 58.1 | 59.6 | 57.8 | |

| Race (%) | ||||

| White | 73.6 | 65.6 | 76.1 | .000 |

| African American | 21.4 | 27.3 | 23.1 | |

| Other | 5.0 | 7.1 | 0.8 | |

| Marital status (%) | .000 | |||

| Married or partnered | 46.4 | 35.9 | 53.1 | |

| Widowed | 33.2 | 48.8 | 30.6 | |

| Divorced/separated | 11.4 | 10.4 | 12.6 | |

| Single, never married | 3.8 | 4.9 | 3.7 | |

| Living arrangement | ||||

| Alone | 30.6 | 34.0 | 31.7 | .000 |

| With spouse | 36.4 | 24.3 | 42.9 | |

| With spouse/others | 9.1 | 9.4 | 9.6 | |

| With others | 18.8 | 32.3 | 15.8 | |

| # of chronic health conditions | 2.84 (1.68) | 3.31 (1.90) | 2.65 (1.56) | .000 |

Note: Bold font indicates statistical significance.

Type of activity

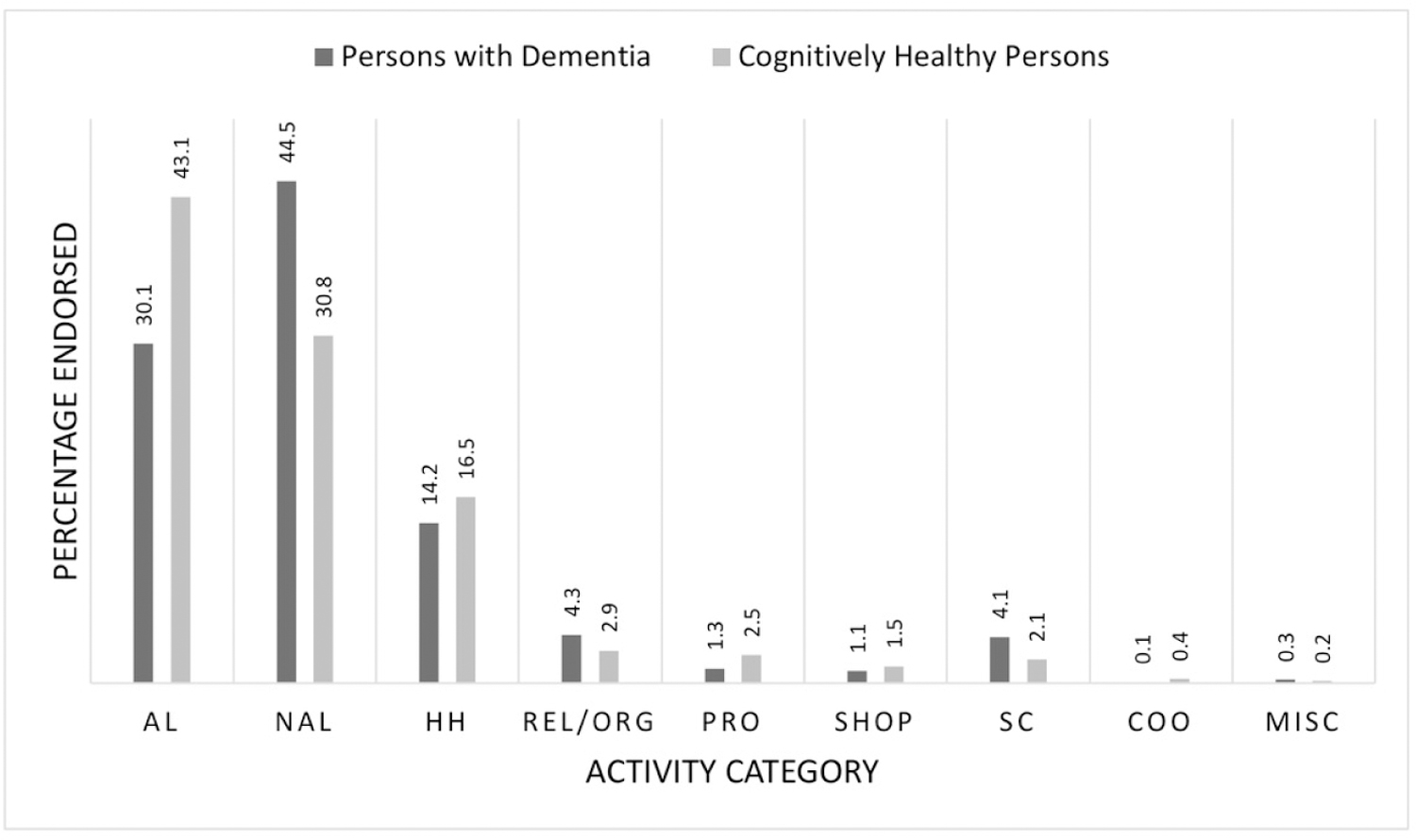

As shown in Figure 1, the most frequently endorsed favorite activity category for PLWD was non-active leisure (44.5%), followed by active leisure (30.1%) and household activities (14.2%). The most common favorite activity category for CHP was active leisure (43.1%), followed by non-active leisure (30.8%) and household activities (16.5%).

Figure 1. Category of favorite activity by cognitive status.

Note. AL=active leisure; NAL=non-active leisure; HH=household; REL/ORG=religious and organizational; PRO=productive; SHOP=shopping; SC=self-care; COO=care of others; MISC=other miscellaneous.

Bivariate correlations

Across the full sample, engagement in favorite activity was significantly correlated with self-rated memory (r = .074, p < .001), self-rated health (r = .138, p < .001), and a number of chronic health conditions (r = −.062, p < .001). These findings indicate that persons who engaged in their favorite activity at any point during the 12 months preceding data collection had higher self-rated memory and health, and fewer chronic health conditions than those persons who did not engage in their favorite activity.

Similarly, for the CHP in the sample, engagement in their favorite activity was significantly correlated with higher self-rated memory (r = .062, p < .001), higher self-rated health (r = .126, p < .001), and fewer chronic health conditions (r = −.043, p < .01). For PLWD, those who engaged in their favorite activity at any point during the 12 months preceding data collection had higher self-rated health (r = .112, p < .001) and higher self-rated memory (r = .063, p < .05). No other correlations were significant.

MANOVA Findings

For the full sample, an overall MANOVA (Table 2) revealed statistically significant differences in measures of cognition, emotion, and function based on whether or not participants engaged in their favorite activity within the past year (F(6,5319) = 17.11, p < .001, Wilk’s Λ = .981, partial ƞ2 = .019), though the effect size was small. Univariate analysis found that all six dependent variables contributed to the significant multivariate effect following a Bonferroni alpha correction: functional status (F(1,5324) = 53.59, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .010), depressed mood (F(1,5324) = 51.91, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .010), anxiety (F(1,5324) = 33.76, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .006), memory (i.e., immediate recall, F(1,5324) = 18.21, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .003; delayed recall, F(1,5324) = 26.37, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .005), and executive function, i.e., Clock Drawing Test (F(1,5324) = 13.08, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .002).

Table 2.

Favorite activity engagement as a predictor of cognition, well-being, and functional status after one year.

| Dementia (n = 1,397) |

No Dementia (n = 4,719) |

P-value (difference) |

Full Sample (n = 6,116) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition | ||||

| Clock drawing | 0.43 (3.75) | 3.64 (1.40)a | .000 | 2.91 (2.56)c |

| Immediate recall | 1.50 (3.46) | 5.15 (1.61)c | .000 | 4.32 (2.66)c |

| Delayed recall | 0.00 (2.75) | 3.85 (1.92)c | .000 | 2.98 (2.68)c |

| Well-being | ||||

| Depression | 3.47 (1.69)b | 2.80 (1.21)c | .000 | 2.95 (1.36)c |

| Anxiety | 3.36 (1.74)a | 2.74 (1.19)c | .000 | 2.88 (1.36)c |

| Functional Status | ||||

| ADL/IADL | 1.78 (1.39)b | 0.55 (0.79)c | .000 | 0.83 (1.09)c |

Note: MANOVA results significant at the p < .008 level after Bonferroni alpha correction.

Note:

= p <.05

= p <.01

= p <.001.

Note: Bold font indicates statistical significance after Bonferroni correction.

Note: ADL=Activities of Daily Living; IADL=Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

For PLWD, the overall MANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference in measures of cognition, emotion, and function based on whether or not participants had engaged in their favorite activity within the past year (F(6,1201) = 3.01, p < .01, Wilk’s Λ = .985, partial ƞ2 = .015), though the effect size was small. Univariate analysis found that functional status (F(1,1206) = 10.67, p < .01, partial ƞ2 = .009) and depressed mood (F(1,1206) = 10.32, p < .01, partial ƞ2 = .008) contributed to the significant multivariate effect following a Bonferroni alpha correction. Anxiety, though initially significant, was no longer statistically significant following alpha correction requirement of significance at p ≤ .008 (F(1,1206) = 5.51, p = .019, partial ƞ2 = .005). Engagement in a favorite activity did not have a significant effect on the memory variables (i.e., immediate recall, F(1,1206) = .013, p =.91, partial ƞ2 = .000; delayed recall, F(1,1206) = .022, p =.88, partial ƞ2 = .000) or executive function, i.e., Clock Drawing Test (F(1,1206) = .320, p =.57, partial ƞ2 = .000) within one year of engagement.

For CHP, the overall MANOVA was significant (F(6,4107) = 11.46, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .016), with a small effect size. Per univariate analysis, five dependent variables contributed to the significant multivariate effect following a Bonferroni alpha correction: functional status (F(1,4112) = 24.93, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .006), depressed mood (F(1,4112) = 35.20, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .008), anxiety (F(1,4112) = 23.05, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .006), and memory (i.e., immediate recall, F(1,4112) = 15.93, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .004; delayed recall, F(1,4112) = 18.19, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .004). Following alpha correction, engagement in favorite activity did not have a significant effect on executive function, i.e., Clock Drawing Test (F(1,4112) = 6.03, p = .014, partial ƞ2 = .001) within one year of engagement.

Discussion

The continued, and perhaps increased, need for meaningful activity in older age is present regardless of cognitive status. However, the ability to meet the need for meaningful engagement may become increasingly challenging as individuals age with cognitive and other health-related changes (Parisi et al., 2017). The findings of this study suggest that having engaged in one’s preferred activity within the past year may have significant benefits related to physical, cognitive, and emotional health for older adults with and without cognitive impairment.

While beneficial to all participants in the study sample, activity engagement exerted differential effects based on cognitive status. For CHP, engagement in one’s favorite activity over the past year positively affected multiple domains, including memory, emotional well-being, functional status, and physical health. This suggests a potential preventive or ameliorating effect of activity engagement, consistent with previous studies (Ashby-Mitchell, Burns, Shaw, & Anstey, 2017; Klinedinst & Resnick, 2016). For PLWD, engagement over the past year had favorable associations with depression and functional health. These findings suggest that assuring that people can engage in activities as they age, regardless of cognitive status, is critical for well-being.

In looking at the effects on immediate and delayed recall, which reflect such concepts as declarative memory, working memory, episodic memory, long-term memory, and retrieval, the cognitive implications could potentially be significant. For example, persons with impaired immediate or delayed recall could have difficulty recalling facts and events (declarative memory), including autobiographical events (episodic memory), holding onto information and using it (working memory), storing information (long-term memory), and recalling that information (retrieval). The significance of these cognitive abilities to independence and everyday activities further underscores the importance of engagement as a preventive measure against cognitive decline for cognitively healthy older adults.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, engagement was assessed as a dichotomous, yes/no variable over the course of one year. Consequently, it is not known how often engagement took place over that time period, nor do we know how recently engagement occurred in relation to the time the question was asked at the end of NHATS year 2, a limitation of the NHATS data set. Nevertheless, we show in this study that engagement in a favorite activity, regardless of frequency, has important benefits. While a longitudinal analysis of the impact of favorite activity engagement would be ideal, there were two barriers to this. First, for NHATS waves 3–6, the sample size of PLWD who reportedly did not engage in their favorite activity was much too low to make any meaningful comparisons with persons with dementia who did engage in their favorite activity. Second, the measurement and wording of the engagement variable made it difficult to characterize the relationship of engagement during one wave with variables collected at a later wave.

An additional limitation of the dataset was the restricted set of outcome variables available, as there may have been other relevant consequences of engaging or not engaging in one’s favorite activity that were not collected. Another possible limitation is the potential for misclassification of dementia status. For example, certain proxies of CHP reported that the NHATS participant had dementia, while the NHATS classification scheme did not support this diagnosis. In addition, the NHATS classification methodology did not take into account functional impairment, which is often associated with cognitive impairment. With respect to proxy respondents, it is not known how accurately proxy report would align with self-report. Finally, more comprehensive measures for mood and various cognitive domains would be ideal, along with more in-depth examination of engagement. The authors recognize that correlation does not equate to causation and, given that it is not known how recently engagement occurred in relation to the time the NHATS yearly survey was taken, it is possible that better cognition, mental health, and function enabled engagement in activity. This should be explored in future research.

Several strengths of the study bear mention. The population-based sample and large sample size increase the likelihood that these findings can be extrapolated to the population as a whole. Additionally, asking participants to identify their favorite activity and inquiring about engagement in that particular activity enabled the authors to examine the impact of a personally meaningful, preferred activity on a variety of outcomes. Many activity questionnaires inquire about participation in predefined activities, which may not capture the full range of activities an older adult is capable of doing. By allowing the participant to define their own favorite activity, the NHATS questionnaire taps into activities imbued with more meaning than ones that are predefined. Although the data did not lend itself to longitudinal analysis using this particular independent variable, our findings serve as an initial step towards a deeper understanding of the benefits of favorite/personally meaningful activity as opposed to just general activity engagement.

Future research should ascertain whether frequency and/or recency of favorite activity engagement were the operative ingredient driving the benefits described herein. Further, although we compared activity category by cognitive status, more research is warranted that examines differential effects on outcome variables by activity type (Regier, Hodgson, & Gitlin, 2017). As prior research found that older adults’ favorite activities are predominantly active (Szanton et al., 2015), and the most frequently endorsed activity category for PLWD was “non-active leisure,” future research should examine differences in activity preferences by cognitive status. While our findings highlight the benefits of preferred activity engagement, more research is needed to examine whether activities that are personally meaningful and valued have benefits beyond those associated with general activity engagement, as suggested by prior studies (Eakman et al., 2010).

As Lawton (2001) noted nearly two decades ago, engagement in meaningful activity is a universal human need, and one that is present regardless of cognitive status. Our findings are consistent with the literature finding that activity engagement has significant benefits in later life, irrespective of cognition (Kuiper et al., 2015; Regier, Hodgson, & Gitlin, 2017; Vikström, Josephsson, Stigsdotter-Neely, & Nygård, 2008). For cognitively healthy persons, favorite activity engagement may mitigate, delay, or prevent declines in function, mood, memory, and executive function. For persons living with dementia, favorite activity engagement may decrease anxiety and improve functional health as well as decrease behavioral symptoms. Given these findings, it is critical that older adults and their support networks maximize opportunities for activity engagement and identify or eliminate potential barriers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data and study materials are publicly available for other researchers at NHATS.org.

Funding

Dr. Regier was supported in part by funding from the National Institute on Aging (K23AG058809). Dr. Gitlin was supported in part by funding from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG041781–01).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

None of the co-authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Adams KB, Leibbrandt S, &, Moon H (2011). A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Aging & Society, 31, 683–712. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X10001091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adenji DO, & Hong M (2019). Factors associated with meaningful activities among ethnically diverse older adults. Innovation in Aging, 3(Suppl 1), S516–S517. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby-Mitchell K, Burns R, Shaw J, & Anstey KJ (2017). Proportion of dementia in Australia explained by common modifiable risk factors. Alzheimers Research and Therapy, 9(1), 11. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0238-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley RC (1989). A continuity theory of normal aging. The Gerontologist, 29(2), 183–190. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley RC (1999). Continuity and adaptation in aging: Creating positive experiences. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Atchley RC (2003). Continuity theory and the evolution of activity in later adulthood. In: Kelly JR (Ed.), Activity and aging: Staying involved in later life. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, & Baltes MM (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimizations with compensation. In Baltes PB & Baltes MM (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Barton C, Ketelle R, Merrilees J, & Miller B (2016). Non-pharmacological management of behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal and other dementias. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 16(2), 14. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0618-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett KM, (2002). Low level social engagement as a precursor of mortality among people in later life. Age and Ageing, 31(3), 165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesedell CE, Cohn ES, & Boyt SBA (2003). Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy (10th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincot, Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Caddell LS, & Clare L (2010). The impact of dementia on self and identity: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(1), 113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor N, & Sanderson CA (1999). Life task participation and well-being: The importance of taking part in daily life. In Kahneman D, Diener E, & Schwarz N (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 230–243). New York: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MC, Kuo JH, Chuang YF, Varma VR, Harris G, Albert MS,…& Fried LP (2015). Impact of the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial on cortical and hippocampal volumes. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 11(11), 1340–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Thein K, Dakheel-Ali M, Regier NG, & Marx MS (2010). The value of social attributes of stimuli for promoting engagement in persons with dementia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(8), 586–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rezende LF, Rey-López JP, Matsudo VK, & do Carmo Luiz O (2014). Sedentary behavior and health outcomes among older adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 14, 333. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakman AM (2011). Convergent validity of the Engagement in Meaningful Activities Survey in a college sample. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 30, 23–32. doi: 10.3928/15394492-20100122-02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakman AM, Carlson ME, & Clark FA (2010a). The Meaningful Activity Participation Assessment: A measure of engagement in personally valued activities. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 70(4), 299–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakman AM, Carlson ME, & Clark FA (2010b). Factor structure, reliability and convergent validity of the Engagement in Meaningful Activities Survey for older adults. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 30, 111–121. doi: 10.3928/15394492-20090518-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakman AM, & Eklund M (2012). The relative impact of personality traits, meaningful occupation, and occupational value on meaning in life and life satisfaction. Journal of Occupational Science, 19(2), 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Flood M (2005). A mid-range nursing theory of successful aging. The Journal of Theory Construction & Testing, 9(2), 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Carlson MC, Freedman M, Frick KD, Glass TA, Hill J,…& Zeger S (2004). A social model for health promotion for an aging population: Initial evidence on the Experience Corps Model. Journal of Urban Health. 81(1), 64–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, Coats MA, Muich SJ, Grant E,…& Morris JC (2005). The AD8: A brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology, 65(4), 559–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Arthur P, Piersol C, Hessels V, Wu SS, Dai Y, & Mann WC (2018). Targeting behavioral symptoms and functional decline in dementia: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(2), 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, & Hauck WW (2010). Targeting and managing behavioral symptoms in individuals with dementia: A randomized trial of a nonpharmacological intervention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(8), 1465–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C, Cruwys T, Milne M, Kan CH, & Haslam SA (2015). Group ties protect cognitive health by promoting social identification and social support. Journal of Aging and Health [e-pub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1177/0898264315589578 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hasselkus BR (2002). The meaning of everyday occupation. New Jersey: Slack. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker SA, Masters KS, Vagnini KM, & Rush CL (2020). Engaging in personally meaningful activities is associated with meaning salience and psychological well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(6), 821–831. [Google Scholar]

- Ikiugu MN (2018). Meaningful and psychologically rewarding occupations: Characteristics and implications for occupational therapy practice. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1080/0164212X.2018.1486768. [DOI]

- James BD, Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, & Bennett DA (2011). Life space and risk of Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline in older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19, 961–969. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318211c219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper JD, Freedman VA, & Spillman BC (2013). Classification of persons by dementia status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. NHATS Technical Paper #5. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved from www.NHATS.org [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, & Jaffe MW (1963). Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association, 185, 914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely DK, & Flacker JM (2003). The protective effect of social engagement on 1-year mortality in a long-stay nursing home population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 56(5), 472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely DK, Simon SE, Jones RN, Morris JN, (2000). The protective effect of social engagement on mortality in long-term care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48,(11), 1367–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinedinst NJ, & Resnick B (2016). The Volunteering-in-Place (VIP) Program: Providing meaningful volunteer activity to residents in assisted living with mild cognitive impairment. Geriatric Nursing, 37(3), 221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, & Löwe B (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Voshaar RCO, Zuidema SU, van den Heuvel ER, Stolk RP, & Smidt N (2015). Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Research Reviews, 22, 39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP (2001). The physical environment of the person with Alzheimer’s disease. Aging & Mental Health, 5(Suppl 1), S56–S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, & Brody EM (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9(3), 179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, & Orleans M (2002). Personhood in a world of forgetfulness: An ethnography of the self process among Alzheimer’s patients. Journal of Aging and Identity, 7(4), 227–244. doi: 10.1023/A:1020709504186 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Low L, Swaffer K, McGrath M, & Brodaty H (2017). Do people with early stage dementia experience Prescribed Disengagement®? A systematic review of qualitative studies. International Psychogeriatrics. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217001545 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mee J, & Sumsion T (2001). Mental health clients confirm the motivating power of occupation. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, Johnson JD, Whitlatch CJ, & Schwartz SM (2012). Activity preferences of persons with dementia. Activities, Adaptation, & Aging, 36(3), 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Edwards B, & Kasper JD (2012). National health and aging trends study round 1 sample design and selection. NHATS Technical Paper #1. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved from www.NHATS.org [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G,…Clark C (1989). The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology, 39(9), 1159–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi JM, Roberts L, Szanton SL, Hodgson NA, & Gitlin LN (2017). Valued activities among individuals with and without cognitive impairments: Findings from the National Health and Aging Trends Study. The Gerontologist, 57(2), 309–318. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson D, Erlandsson LK, Eklund M, & Iwarsson S (2001). Value dimensions, meaning, and complexity in human occupation – A tentative structure for analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 8, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney A (2006). Family strategies for supporting involvement in meaningful activity by persons with dementia. Journal of Family Nursing, 12(1), 80–101. doi: 10.1177/1074840705285382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney A, Chaudhury H, & O’Connor DL (2007). Doing as much as I can do: The meaning of activity for people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 11(4), 384–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, & McMillan D (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier NG, Hodgson NA, & Gitlin RN (2017). Characteristics of activities for persons with dementia at the mild, moderate and severe stages. The Gerontologist, 57(5), 987–997. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schretlen DJ, Testa SM, & Pearlson GD (2010). Clock-drawing test scoring approach from the Calibrated Neuropsychological Normative System. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Spector WD, & Fleishman JA (1998). Combining activities of daily living with instrumental activities of daily living to measure functional disability. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(1), S46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaffer K (2015). Dementia and prescribed disengagement. Dementia, 14(1), 3–6. doi: 10.1177/1471301214548136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szanton SL, Walker RK, Roberts L, Thorpe RJ, Wolfe J, Agree E, Roth DL,…& Seplacki C (2015). Older adults’ favorite activities are resoundingly active: Findings from the NHATS study. Geriatric Nursing, 36, 131–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PA (2012). Trajectories of social engagement and mortality in late life. Journal of Aging & Health, 24(4), 547–568. doi: 10.1177/0898264311432310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson G (2003). On the meaning of life. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Thomson Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Tomori K, Nagayama H, Saito Y, Ohno K, Nagatani R, & Higashi T (2015). Examination of a cut-off score to express the meaningful activity of people with dementia using iPad application (ADOC). Disability and Rehabilitation, 10(2), 126–131. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2013.871074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikström S, Josephsson S, Stigsdotter-Neely A, & Nygård L (2008). Engagement in activities: Experiences of persons with dementia and their caregiving spouses. Dementia, 7(2), 251–270. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf-Klein GP, Silverstone FA, Levy AP, & Brod MS (1989). Screening for Alzheimer’s disease by clock drawing. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 37(8), 730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.