Abstract

Primary prevention and interception of chronic lung disease are essential in the effort to reduce the morbidity and mortality caused by respiratory conditions. In this review, we apply a life course approach that examines exposures across the life span to identify risk factors that are associated with not only chronic lung disease but also an intermediate phenotype between ideal lung health and lung disease, termed “impaired respiratory health.” Notably, risk factors such as exposure to tobacco smoke and air pollution, as well as obesity and physical fitness, affect respiratory health across the life course by being associated with both abnormal lung growth and lung function decline. We then discuss the importance of disease interception and identifying those at highest risk of developing chronic lung disease. This work begins with understanding and detecting impaired respiratory health, and we review several promising molecular biomarkers, predictive symptoms, and early imaging findings that may lead to a better understanding of this intermediate phenotype.

Key Words: biomarkers, COPD, interstitial lung disease, lung health

Abbreviations: ESCAPE, European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects; ILA, interstitial lung abnormality; ILD, interstitial lung disease; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; LLN, lower limit of normal; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase

There has been growing interest in the primary prevention of chronic lung disease. Focusing on primary prevention can have a substantial effect on the overall health of the population by finding upstream solutions to keep individuals healthy and prevent the development of disease. In the cardiovascular field, emphasizing the study of cardiovascular risk factors and promoting ideal cardiovascular health have contributed greatly to the decline in mortality from heart disease seen over the last several decades.1 Accordingly, in the field of respiratory health, an increasing number of observational and longitudinal studies have aimed to study the risk factors associated with the development of impaired lung function and lung disease.

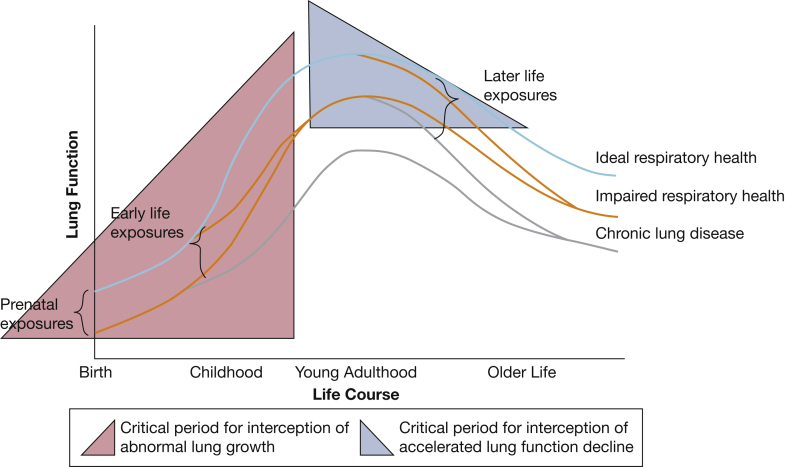

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has highlighted the importance of using a life course approach to address the promotion of lung health.2 This approach refers to the long-term effects from exposures across the life span, including gestation, childhood, adolescence, and later life, and the potential for accumulation of these risks.3 This approach builds on the Barker hypothesis, which proposes that adult disease often has its origins in early development, particularly intrauterine development.4,5 Our group previously proposed a conceptual model of respiratory health centered on identifying impaired respiratory health as an intermediate phenotype on the continuum between ideal respiratory health and chronic lung disease.6 This approach focuses on identifying risk factors from early life to young adulthood that may serve as targets for interception of impaired health before it becomes disease.6 In this review, we will use this conceptual framework and build on that model by using a life course approach to review the risk factors that may contribute to the transition from ideal respiratory heath to impaired respiratory health to chronic respiratory disease through associations with lung growth, lung function decline, or both (Fig 1).7,8 We then discuss areas of active research into objective measures and biomarkers of impaired respiratory health.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of respiratory health (adapted from the work of Fletcher and Peto,7 Lange and colleagues,8 and Reyfman and colleagues6) that builds on prior conceptual frameworks of lung health trajectories to include the association of life course exposures with the development of impaired respiratory health and chronic lung disease. Prenatal and early life exposures are associated with abnormal lung growth and may be associated with impaired respiratory health or lung disease starting in infancy. Later life exposures are associated with the rate of lung function decline. Highlighted in blue is the critical period for interception of abnormal lung growth, which includes the prenatal period up until peak lung function is attained in young adulthood. Highlighted in pink is the critical period for interception of accelerated lung function decline, which begins in young adulthood and continues through middle age.

Impaired Respiratory Health: An Intermediate Phenotype Between Health and Disease

In 1977, Burrows and colleagues9 fundamentally influenced our understanding of the development of COPD by showing that childhood respiratory disorders are associated with both decreased peak lung function and excessive decline in lung function later in life. These findings helped promote a model of varied lung function trajectories of growth and decline over the life course.7,8 Following lung function trajectories over time allows for the identification of populations with ideal respiratory health, impaired respiratory health, and respiratory disease (Fig 1).

Even when impaired lung function may be considered normal by clinical standards (ie, > 80% predicted), having lower lung function on the basis of spirometry is associated with increased risk of future lung disease, cardiovascular morbidity, and all-cause mortality.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Authors in several longitudinal studies have examined subjects who would not be considered to have COPD on the basis of a fixed FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7 but have a ratio less than the lower limit of normal (LLN) on the basis of sex- and age-specific criteria. These studies have showed that such people have higher rates of respiratory symptoms, respiratory exacerbations, cardiovascular morbidities, and higher all-cause mortality than do individuals with an FEV1/FVC ratio higher than the LLN.18, 19, 20, 21

It has been proposed that “early COPD” should be distinguished from “mild COPD,” and Martinez and colleagues22 have defined early COPD as occurring in individuals younger than 50 years with a smoking history ≥ 10 pack-years and an FEV1/FVC ratio less than LLN, compatible CT abnormalities, or evidence of accelerated FEV1 decline (≥ 60 mL/year). Studies have shown that among individuals younger than 50 years with ≥ 10 pack-years, those with early COPD are six times more likely to develop clinical COPD, and they have greater chronic respiratory symptoms, respiratory hospitalizations, and all-cause mortality than do those without early COPD.23,24

Early COPD is a well-studied example of impaired respiratory health. However, there remain questions about whether strict thresholds of age, smoking pack-years, FEV1/FVC ratio, and FEV1 decline enhance or limit its use as compared with viewing impaired respiratory health on a continuum. When early COPD was studied in two different population-based cohorts, among smokers with < 10 pack-years, individuals otherwise meeting early COPD criteria were 10 times more likely to develop clinical COPD within 10 years than were those without early COPD (10% vs 1%).23 Similarly, among never smokers, those meeting early COPD criteria were also more likely to develop clinical COPD than were those without early COPD (3% vs < 1%).

These studies stress the importance of longitudinal cohorts dedicated to the study of lung health. It is vital to follow the natural progression of those with early COPD and other types of impaired respiratory health to understand why some individuals develop clinical disease, whereas others continue to have impaired lung health, and to answer the questions of whether and how some may transition back to ideal lung health. We contend that taking a broad view of lung health that incorporates all intermediate phenotypes of impaired respiratory health, including those that may transition into restrictive or interstitial lung disease (ILD), is important from a public health perspective.

Çolak and colleagues13 illustrated the importance of ideal respiratory health in a study in which they found that having supernormal lung function (FVC > upper limit of normal) was associated with fewer future hospitalizations for respiratory and cardiovascular events and decreased all-cause mortality over 15 years of follow-up, compared with having normal lung function (FVC ≥ LLN and ≤ ULN). Additionally, Bui and colleagues25 identified a novel lung function trajectory that begins with low lung function in childhood but exhibits accelerated growth. This catch-up phenomenon was seen most commonly in children with low birth weight and may hold the key to intercepting impairments in peak lung function in young adulthood.

Although impaired lung health is a likely precursor of lung disease, this relationship may not be universal. Additionally, although ideal respiratory health may be represented on a research and population basis by supernormal lung function, it remains unclear how it should be defined on an individual basis. For instance, Bui and colleagues25 demonstrated a distinct lung function trajectory with accelerated growth, but it is unclear whether ideal lung health is achievable for all individuals with impaired respiratory health.

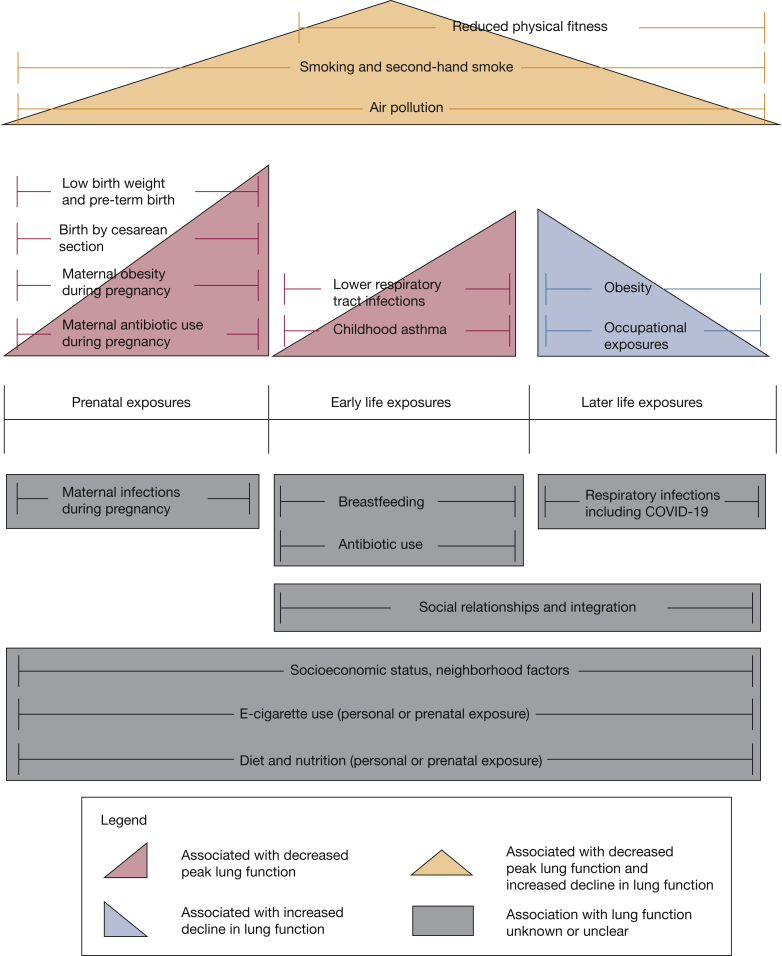

Although these questions remain, we argue that identifying impaired respiratory health provides an important conceptual framework for considering the prevention and interception of chronic lung disease. Respiratory disease and impaired respiratory health can be the result of abnormal lung growth or accelerated lung function decline later in adult life. Various risk factors throughout the life course may be associated with abnormal lung growth, lung function decline, or both (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Above the life course timeline are exposures associated with impaired respiratory health and chronic lung disease. Below the life course timeline are areas that have gaps in knowledge regarding the effect on respiratory health and that provide points for future and ongoing research.

Prenatal Exposures and Association With Lung Growth

It is now well established that early life events, including those occurring during gestation, may increase the risk of COPD developing.4,26,27 Decreased lung function and increased bronchial hyperresponsiveness in neonates has been associated with increased risk of developing asthma at age 7 years.28 Low lung function in infancy has also been shown in multiple studies to be associated with reduced lung function in childhood and young adulthood.29,30 Berry and colleagues30 found that infants in the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study with lung function in the lowest quartile were more likely to have the lowest lung function at ages 11, 16, and 22 years, compared with the upper 3 quartiles combined, independent of wheezing, smoking, atopy, or parental asthma.

Prenatal secondhand smoke exposure from maternal smoking during pregnancy is a significant risk factor for poor lung function later in life. A meta-analysis showed it was associated with an at least 20% increased risk of incident wheeze and asthma in children and young adults.31 Moshammer and colleagues32 pooled data from eight different cohort studies and found smoking during pregnancy was associated with a 40% increased risk of poor lung function, as measured with maximal midexpiratory flow < 75% predicted, in children ages 6 through 12 years, even when adjusted for current environmental tobacco smoke exposure.

It is still uncertain what effect prenatal exposure to nicotine alone or e-cigarette vapor may have on subsequent lung function. Prenatal nicotine exposure led to decreased lung function in rhesus monkeys and mice, as well as increased airway hyperresponsiveness in mice.33, 34, 35 Additionally, prenatal exposure to e-cigarette vapor (with or without nicotine) in mice led to alterations in inflammatory markers in the lungs of offspring, as well as increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor α, a protein important to lung development and associated with lung fibrosis.36 Dhalwani and colleagues37 studied the use of nicotine replacement therapy during pregnancy and, although limited by a small number of exposed cases, found it was significantly associated with increased respiratory abnormalities but no other congenital anomalies.

Aside from tobacco smoke exposure, several other prenatal risk factors are associated with impaired lung function in childhood and young adulthood. Low birth weight was associated with decreased lung volumes and lung function in young adulthood in several longitudinal studies.4,38, 39, 40, 41, 42 Prenatal exposure to air pollution is associated with decreased lung function and development of asthma in childhood, independent of postnatal exposure to pollution and tobacco smoke.43 Additionally, maternal antibiotic use during pregnancy and birth by cesarean section have both been associated with increased risk of asthma development in children, thought to be due to alterations of the microbiome to which the child is exposed.44, 45, 46 Finally, a meta-analysis of 24 cohort studies showed maternal obesity during pregnancy to be a significant risk factor in the development of asthma in offspring.47 This state is hypothesized potentially to be mediated by elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines associated with asthma in pregnant women who are obese, alterations in diet and vitamin D deficiency, or shared genetic polymorphisms.

Early Life Exposures and Association With Lung Growth

Childhood exposures to both tobacco smoke and air pollution have been associated with increased rates of asthma and lower lung function in childhood.31,48, 49, 50, 51, 52 In a prospective study of children in southern California, those living in communities with the highest levels of air pollution had a nearly 5 times greater risk of having an FEV1 < 80% predicted at age 18 years compared with those living in communities with the lowest air pollution.49 Additionally, exposure to air pollution from the ages of 1 through 4 years was independently associated with chronic bronchitis in young adults from the BAMSE (Swedish abbreviation for Child, Allergy, Milieu, Stockholm, Epidemiological) study, which followed up participants from birth to age 24 years.52

Indoor air pollutants are a major contributor to poor lung health globally. The World Health Organization estimates that 52% of the world’s population cook and heat with solid biomass (wood, crop waste, animal dung) and coal.53 Burning biomass indoors creates high concentrations of air pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, and inhalable particulate matter.54 One cross-sectional study in Nepal suggesting an association between biomass exposure and lung development showed that among teenagers and young adults (aged 16-25 years), mean FEV1 was 225 mL lower in those exposed to biomass smoke than in those not exposed.55

Lower respiratory tract infections in infancy and early childhood are associated with increased risk of developing asthma and abnormal lung growth.30,40,56,57 In one prospective birth cohort study, lower respiratory tract infections during infancy were associated with lower FEV1 at age 43 years among smokers.58 The authors of this study also performed a meta-regression analysis of other cohort studies and found that the degree of FEV1 deficit in adulthood associated with early lower respiratory tract infections was itself associated with the percentage of the cohort who had smoked cigarettes. This finding suggests a synergistic detrimental relationship between early life exposures and smoking on lung growth.

There is also evidence to suggest that physical fitness is an important determinant of lung development. Greater improvements in fitness during childhood and adolescence are associated with greater increases in FEV1 and FVC from ages 9 to 26 years.59 In a recent systematic review, Ferreira and colleagues60 examined the association of obesity with lung function in childhood and adolescence and found that although there was a trend toward reduced lung function in children and adolescents who were obese, there was high variability in the study results, which did not allow them to reach a consensus.

Other early life exposures do not have as clear of an association with lung function later in life. Although antibiotic use during infancy has been associated with increased risk of asthma development, this relationship does not always persist when adjusted for lower respiratory tract infections.61,62 Similarly, despite breastfeeding being associated with fewer lower respiratory tract infections in childhood, there have been variable associations between breastfeeding and future risk of developing asthma or impaired lung function.52,63, 64, 65, 66

Childhood asthma also has a significant association with abnormal lung growth. Persistent or relapsing asthma is associated with impaired lung function that continues from childhood to adulthood.67 Additionally, among children with mild to moderate persistent asthma who were followed up for an average of 13 years, 75% had an abnormal lung function trajectory—exhibiting reduced lung growth, early functional decline, or both.68 Children with asthma also have increased rates of chronic bronchitis as young adults and worse lung function and increased rates of COPD at age 53 years.48,52

Later Life Exposures and Association With Lung Function Decline

Smoking tobacco products is a well-established risk factor for chronic lung diseases and is also highly associated with increased lung function decline. Heavy stable smokers compared with never smokers have nearly 8 times the odds of obstructive lung physiology and 20 times the odds of emphysema as measured with CT scanning after 25 years of follow-up.69 Even those with low-intensity sustained smoking show up to a 5 times greater rate of FEV1 decline and higher odds of having emphysema on CT scans when compared with those who quit smoking, despite having fewer lifetime pack-years.69,70 In the Lung Health Study, a clinical trial of smoking cessation intervention in middle-aged smokers with mild to moderate COPD, those who continued smoking had a decline in FEV1 of 301 mL over 5 years as compared with 72 mL in those with sustained smoking cessation.71 Smoking is also a recognized risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA).72,73 There does, however, remain a gap in knowledge about the minimum threshold for smoking risk and how longitudinal trajectories of smoking are associated with other measures of lung health.

Currently, there are very few data on the long-term effects of e-cigarettes. Among people who do not have respiratory disease at baseline, current e-cigarette use is independently associated with higher incident respiratory disease during 2 years of follow-up.74 However, these findings may have been affected by reverse causality in which smokers with early undiagnosed respiratory disease initiate e-cigarette use under the belief e-cigarettes might be therapeutic or less harmful. However, dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco is associated with an even higher incidence of new respiratory disease than is either product alone.74

Air pollution is associated with lung health throughout the life course and may affect not only lung growth but also lung function decline. In the longitudinal Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, which included adults ages 45 to 84 years from six US metropolitan areas, higher baseline concentrations of ozone, inhalable particulate matter, nitrogen oxide, and black carbon were associated with greater increases in the percentage of emphysema seen on CT scans over 10 years.75 Data from the UK Biobank, as well as the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE) and the LifeLines Cohort Study, show that exposure to higher concentrations of inhalable particulate matter in adults is associated with obstructive and restrictive patterns of impaired lung health (lower levels of FEV1 and FVC, respectively).76, 77, 78 Additionally, the ESCAPE and LifeLines Cohort studies found these associations to be strongest in those with higher BMI.76,78 The authors of the study using the ESCAPE cohort hypothesized this may be due to a synergistic effect between obesity and air pollution on systemic inflammation, as suggested in prior studies.78, 79, 80

Several studies have showed that burning biomass for fuel is also a significant risk factor for the development of COPD, particularly in nonsmokers.81,82 In a cross-sectional study of individuals living in the same community in Brazil, there was a negative dose-response relationship between both duration and amount of biomass smoke exposure and FEV1.83 This relationship was found in both smokers and nonsmokers. Studies of environmental risk factors for IPF, including one meta-analysis of six case-control studies, have showed the strongest evidence linking metal dust and stone or sand exposure and IPF, but there also exists evidence that work with agriculture or farming, livestock, and wood dust may also be risk factors.84,85

It is now well accepted that obesity is negatively associated with respiratory health and lung function.86,87 Obesity has also been associated with the rate of lung function decline.88 Young healthy adults with a baseline BMI in the top quartile (corresponding to BMI ≥ 26.3 kg/m2) have significantly greater decline in lung function over 10 years than do those with a lower baseline BMI.88 This association was similar and remained significant when examining only individuals who were never smokers and without asthma. Studies using bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis to evaluate the relationship between obesity and asthma showed evidence supporting a causal effect of BMI on risk of asthma but no clear evidence of asthma causing increased BMI.89,90

Apart from obesity, physical fitness has also been associated with future lung function decline.91,92 Among young adults in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults longitudinal cohort, higher baseline cardiorespiratory fitness, on the basis of treadmill exercise testing, was associated with less decline in FEV1 and FVC over 20 years of follow-up.91 Change in fitness over time was also directly proportional to change in lung function, and this relationship was significant in never smokers, light smokers, and heavy smokers. In this cohort, sustaining higher fitness and improving fitness over 20 years were both associated with preservation of lung health, perhaps mediated by decreased systemic inflammation.

Advancing the Agenda for Disease Interception

There remain gaps in knowledge surrounding the effect of certain exposures on respiratory health (Fig 2). Some notable areas for future and ongoing research are the effect of diet and nutrition, as well as e-cigarette use, on lung development and lung function decline. Nonetheless, the identification of risk factors has had a notable effect on the primary prevention of lung disease. Although primary prevention is vital to reduce the burden of lung disease, disease interception is another strategy that has the potential to have a tremendous effect on preventing lung disease. Disease interception begins with the detection of those with impaired health and then intervening to reverse or slow the development of disease. This method includes efforts to refine criteria to recognize people with early COPD to implement interventions that might prevent clinical COPD.22,27 Another example is the Vitamin C to Decrease the Effects of Smoking in Pregnancy on Infant Lung Function clinical trial, which examined the use of vitamin C in pregnant mothers who smoke to mitigate the effects of prenatal smoke exposure on infant lung function.93 Similarly, vitamin D supplementation may be beneficial in preventing acute respiratory tract infections, which are associated with abnormal lung growth.94

However, because there are few life course studies beginning in young adulthood focused primarily on lung health, it is difficult to conceptualize how an individual might progress from ideal health to impaired respiratory health to chronic lung disease. In research settings and in longitudinal studies that follow up subjects over decades, impaired respiratory health is most commonly assessed through the use of spirometry. However, picking up on changes that may signal impaired respiratory health often requires serial measurements over long periods, which can be impractical. Additionally, Agustí and Hogg95 have hypothesized that people who have a supernormal lung function trajectory may incur substantial lung damage before it is detected by traditional spirometric standards. Spirometry also likely does not capture all the facets of ideal lung health. Regan and colleagues96 found that smokers without spirometric airflow obstruction (defined by FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7) commonly had respiratory complaints and worse quality of life, lower 6-minute walk distance, and higher incidence of emphysema and airway thickening on CT scans than did never smokers. Several tools other than pulmonary function tests, including molecular biomarkers, assessment of predictive symptoms, and CT imaging, are useful in identifying the intermediate phenotype of impaired respiratory health (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tools Other Than Pulmonary Function Tests to Detect Impaired Respiratory Health

| Tool | Associations |

|---|---|

| Molecular biomarkers | |

| CRP, fibrinogen | Reduced FVC, reduced FEV1; future emphysema |

| ICAM-1 | Reduced FVC, reduced FEV1; future emphysema, high-attenuation areas, ILA, IPF, ILD-specific death |

| MMP-7 | Reduced FVC, exertional dyspnea, ILA, all-cause mortality |

| Assessment of symptoms | |

| Cough or phlegm | Decline in FVC, decline in FEV1; future obstructive physiology, future emphysema |

| Respiratory illnesses | Decline in FVC, decline in FEV1; future obstructive physiology, future emphysema |

| Shortness of breath | Future restrictive physiology, increased all-cause mortality |

| COPD Assessment Test score > 10 in smokers without COPD | Reduced FVC, reduced FEV1, respiratory exacerbations requiring use of antibiotics or corticosteroids |

| CT imaging | |

| Low-attenuation areas | Increased all-cause mortality in a general population without COPD |

| High-attenuation areas | Lower FVC; future ILA, ILD-specific hospitalizations, ILD-specific mortality, all-cause mortality |

| ILA | Reduced lung capacity, reduced exercise capacity, reduced gas exchange, all-cause mortality |

CRP = C-reactive protein; ICAM = intercellular adhesion molecule; ILA = interstitial lung abnormalities; ILD = interstitial lung disease; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; MMP = matrix metalloproteinase.

Given how the discovery of hypercholesterolemia as a biomarker on the causal pathway of atherosclerosis led to advances in the interception of cardiovascular disease, there has been considerable interest in finding a molecular biomarker for impaired lung health. Prior longitudinal cohort studies have shown that elevations in markers of systemic inflammation and endothelial activation, such as C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, in young adults are associated with abnormal lung function and abnormal CT imaging in middle age.97, 98, 99 ICAM-1 levels have also been associated greater odds of future ILD-specific hospitalizations and mortality.99 Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-7 has been implicated in extracellular matrix remodeling in the lung and the development of fibrosis.100 MMP-7 is associated with reduced FVC and higher odds of exertional dyspnea after 5 years of follow-up and higher odds of interstitial changes on CT scans after 10 years of follow-up.101 MMP-7 levels in those with subclinical ILD on the basis of imaging are significantly higher than those in healthy control subjects but significantly lower than those in people with IPF.102 This finding suggests that MMP-7 may be an ideal biomarker to identify people who have an interstitial phenotype of impaired respiratory health and who are at highest risk of developing pulmonary fibrosis in the future.

Similarly, respiratory symptoms such as cough, phlegm, shortness of breath, and chest illnesses are predictive of future lung function decline, respiratory exacerbations and hospitalizations, and even increased all-cause mortality.103, 104, 105, 106, 107 Rodriguez-Roisin and colleagues108 have raised the question of whether the presence of chronic respiratory symptoms in ever smokers with preserved lung function may be an early phase of COPD or whether it is a separate, smoking-related condition without progression to obstructive lung disease. Different symptoms may even indicate different phenotypes of impaired lung health, given that cough-related symptoms are associated with future obstructive physiology and emphysema and shortness of breath is associated with future restrictive physiology.103

CT imaging is another promising tool for detecting impaired lung health. Low-attenuation areas (termed “emphysema-like lung”) on CT scans of individuals without airflow obstruction or COPD are associated with increased mortality after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors and FEV1.109 ILA are seen in approximately 7% of the adult population and are defined as specific patterns of increased lung density on CT scans in people with no history of ILD.73,110 ILA are likely both a precursor to ILD and also an indicator of overall impaired lung health. ILA are associated with reductions in lung capacity, exercise capacity, and gas exchange, as well as increased all-cause mortality, with a higher rate of death from respiratory causes.73,111,112 There is evidence that high-attenuation areas on CT scans represent areas of lung injury. High-attenuation areas are associated with lower FVC, increased risk of future ILA, ILD-specific hospitalization, ILD-specific mortality and all-cause mortality.113,114

Conclusions

Primary prevention and interception of lung disease is an achievable goal with use of a life course approach to understand better ideal respiratory health and the exposures that can lead to impaired respiratory health and chronic lung disease. Considerable achievements have been made in the discovery of prenatal, childhood, and later life risk factors for impaired respiratory health and lung disease. However, additional life course studies dedicated to respiratory health are needed to understand better the transition to impaired lung health and any associated biomarkers, symptoms, or imaging findings. Identifying markers of impaired respiratory health will make it possible to design interventions to halt this transition and intercept chronic lung disease at the earliest stages.

Acknowledgments

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: R. K. reports personal fees from Aptus Health, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Boston Consulting Group, personal fees from Boston Scientific, personal fees from CVS Caremark, grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, grants from PneumRx (BTG), and grants from Spiration, all outside the submitted work. None declared (G. Y. L.).

References

- 1.Mensah G.A., Wei G.S., Sorlie P.D. Decline in cardiovascular mortality. Circ Res. 2017;120(2):366–380. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camargo C.A., Budinger G.R.S., Escobar G.J. Promotion of lung health: NHLBI workshop on the primary prevention of chronic lung diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(suppl 3):S125–S138. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-451LD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Shlomo Y., Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker D.J., Godfrey K.M., Fall C., Osmond C., Winter P.D., Shaheen S.O. Relation of birth weight and childhood respiratory infection to adult lung function and death from chronic obstructive airways disease. BMJ. 1991;303(6804):671–675. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6804.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker D.J.P., Osmond C., Winter P.D., Margetts B., Simmonds S.J. Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1989;334(8663):577–580. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reyfman P.A., Washko G.R., Dransfield M.T., Spira A., Han M.K., Kalhan R. Defining impaired respiratory health: a paradigm shift for pulmonary medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(4):440–446. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0120PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher C., Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. BMJ. 1977;1(6077):1645–1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lange P., Celli B.R., Agustí García-Navarro À. Lung-function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):111–122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burrows B., Knudson R.J., Lebowitz M.D. The relationship of childhood respiratory illness to adult obstructive airway disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115(5):751–760. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.115.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hole D.J., Watt G.C.M., Davey-Smith G., Hart C.L., Gillis C.R., Hawthorne V.M. Impaired lung function and mortality risk in men and women: findings from the Renfrew and Paisley prospective population study. BMJ. 1996;313(7059):711–715. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7059.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mannino D.M., Buist A.S., Petty T.L., Enright P.L., Redd S.C. Lung function and mortality in the United States: data from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey follow up study. Thorax. 2003;58(5):388–393. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannino D.M., Doherty D.E., Sonia Buist A. Global Initiative on Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classification of lung disease and mortality: findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Respir Med. 2006;100(1):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Çolak Y., Nordestgaard B.G., Vestbo J., Lange P., Afzal S. Relationship between supernormal lung function and long-term risk of hospitalisations and mortality: a population-based cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(4):2004055. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04055-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mannino D.M., Diaz-Guzman E. Interpreting lung function data using 80% predicted and fixed thresholds identifies patients at increased risk of mortality. Chest. 2012;141(1):73–80. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agustí A., Noell G., Brugada J., Faner R. Lung function in early adulthood and health in later life: a transgenerational cohort analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(12):935–945. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30434-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasquez M.M., Zhou M., Hu C., Martinez F.D., Guerra S. Low lung function in young adult life is associated with early mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(10):1399–1401. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201608-1561LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sin D.D., Wu L., Man S.F.P. The relationship between reduced lung function and cardiovascular mortality: a population-based study and a systematic review of the literature. Chest. 2005;127(6):1952–1959. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akkermans R.P., Biermans M., Robberts B. COPD prognosis in relation to diagnostic criteria for airflow obstruction in smokers. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(1):54–63. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00158212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerveri I., Corsico A.G., Accordini S. Underestimation of airflow obstruction among young adults using FEV1/FVC <70% as a fixed cut-off: a longitudinal evaluation of clinical and functional outcomes. Thorax. 2008;63(12):1040–1045. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.095554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pothirat C., Chaiwong W., Phetsuk N., Liwsrisakun C. Misidentification of airflow obstruction: prevalence and clinical significance in an epidemiological study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:535–540. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S80765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Çolak Y., Afzal S., Nordestgaard B.G., Vestbo J., Lange P. Young and middle-aged adults with airflow limitation according to lower limit of normal but not fixed ratio have high morbidity and poor survival: a population-based prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(3):1702681. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02681-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez F.J., Han M.K., Allinson J.P. At the root: defining and halting progression of early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(12):1540–1551. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-2028PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Çolak Y., Afzal S., Nordestgaard B.G., Lange P., Vestbo J. Importance of early COPD in young adults for development of clinical COPD: findings from the Copenhagen General Population Study [published online ahead of print November 3, 2020]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202003-0532OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Çolak Y., Afzal S., Nordestgaard B.G., Vestbo J., Lange P. Prevalence, characteristics, and prognosis of early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Copenhagen General Population Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;201(6):671–680. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1644OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bui D.S., Lodge C.J., Burgess J.A. Childhood predictors of lung function trajectories and future COPD risk: a prospective cohort study from the first to the sixth decade of life. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(7):535–544. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Postma D.S., Bush A., van den Berge M. Risk factors and early origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2015;385(9971):899–909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rennard S.I., Drummond M.B. Early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: definition, assessment, and prevention. Lancet. 2015;385(9979):1778–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60647-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bisgaard H., Jensen S.M., Bønnelykke K. Interaction between asthma and lung function growth in early life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(11):1183–1189. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1922OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stern D.A., Morgan W.J., Wright A.L., Guerra S., Martinez F.D. Poor airway function in early infancy and lung function by age 22 years: a non-selective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):758–764. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61379-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berry C.E., Billheimer D., Jenkins I.C. A distinct low lung function trajectory from childhood to the fourth decade of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(5):607–612. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0753OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke H., Leonardi-Bee J., Hashim A. Prenatal and passive smoke exposure and incidence of asthma and wheeze: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):735–744. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moshammer H., Hoek G., Luttmann-Gibson H. Parental smoking and lung function in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(11):1255–1263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1552OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sekhon H.S., Keller J.A., Benowitz N.L., Spindel E.R. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters pulmonary function in newborn rhesus monkeys. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(6):989–994. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.6.2011097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spindel E.R., McEvoy C.T. The role of nicotine in the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on lung development and childhood respiratory disease: implications for dangers of e-cigarettes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(5):486–494. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2013PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wongtrakool C., Wang N., Hyde D.M., Roman J., Spindel E.R. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters lung function and airway geometry through α7 nicotinic receptors. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46(5):695–702. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0028OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen H., Li G., Chan Y.L. Maternal e-cigarette exposure in mice alters DNA methylation and lung cytokine expression in offspring. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;58(3):366–377. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0206RC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dhalwani N.N., Szatkowski L., Coleman T., Fiaschi L., Tata L.J. Nicotine replacement therapy in pregnancy and major congenital anomalies in offspring. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):859–867. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards C.A., Osman L.M., Godden D.J., Campbell D.M., Douglas J.G. Relationship between birth weight and adult lung function: controlling for maternal factors. Thorax. 2003;58(12):1061–1065. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.12.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hancox R.J., Poulton R., Greene J.M., McLachlan C.R., Pearce M.S., Sears M.R. Associations between birth weight, early childhood weight gain and adult lung function. Thorax. 2009;64(3):228–232. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.103978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tennant P.W.G., Gibson G.J., Pearce M.S. Lifecourse predictors of adult respiratory function: results from the Newcastle Thousand Families Study. Thorax. 2008;63(9):823–830. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.096388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rona R.J., Gulliford M.C., Chinn S. Effects of prematurity and intrauterine growth on respiratory health and lung function in childhood. BMJ. 1993;306(6881):817–820. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6881.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawlor D., Ebrahim S., Davey S. Association of birth weight with adult lung function: findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2005;60(10):851–858. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.042408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Korten I., Ramsey K., Latzin P. Air pollution during pregnancy and lung development in the child. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2017;21:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lapin B., Piorkowski J., Ownby D. Relationship between prenatal antibiotic use and asthma in at-risk children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114(3):203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metsälä J., Lundqvist A., Virta L.J., Kaila M., Gissler M., Virtanen S.M. Prenatal and post-natal exposure to antibiotics and risk of asthma in childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(1):137–145. doi: 10.1111/cea.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keag O.E., Norman J.E., Stock S.J. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forno E., Young O.M., Kumar R., Simhan H., Celedón J.C. Maternal obesity in pregnancy, gestational weight gain, and risk of childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e535–e546. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bui D.S., Walters H.E., Burgess J.A. Childhood respiratory risk factor profiles and middle-age lung function: a prospective cohort study from the first to sixth decade. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(9):1057–1066. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201806-374OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gauderman W.J., Avol E., Gilliland F. The effect of air pollution on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1057–1067. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Belgrave D.C.M., Granell R., Turner S.W. Lung function trajectories from pre-school age to adulthood and their associations with early life factors: a retrospective analysis of three population-based birth cohort studies. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(7):526–534. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guerra S., Stern D.A., Zhou M. Combined effects of parental and active smoking on early lung function deficits: a prospective study from birth to age 26 years. Thorax. 2013;68(11):1021–1028. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang G., Hallberg J., Bergström P.U. Assessment of chronic bronchitis and risk factors in young adults: results from BAMSE. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(3):2002120. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02120-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.World Health Organization Indoor air pollution and household energy. https://www.who.int/heli/risks/indoorair/indoorair/en/

- 54.Pierson W.E., Koenig J.Q., Bardana E.J. Potential adverse health effects of wood smoke. West J Med. 1989;151(3):339–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurmi O.P., Devereux G.S., Smith W.C.S. Reduced lung function due to biomass smoke exposure in young adults in rural Nepal. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(1):25–30. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00220511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaheen S.O., Barker D.J.P., Holgate S.T. Do lower respiratory tract infections in early childhood cause chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(5):1649–1652. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.5_Pt_1.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chan J.Y.C., Stern D.A., Guerra S., Wright A.L., Morgan W.J., Martinez F.D. Pneumonia in childhood and impaired lung function in adults: a longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):607–616. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allinson J.P., Hardy R., Donaldson G.C., Shaheen S.O., Kuh D., Wedzicha J.A. Combined impact of smoking and early-life exposures on adult lung function trajectories. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(8):1021–1030. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0506OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hancox R.J., Rasmussen F. Does physical fitness enhance lung function in children and young adults? Eur Respir J. 2018;51(2):1701374. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01374-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferreira M.S., Marson F.A.L., Wolf V.L.W., Ribeiro J.D., Mendes R.T. Lung function in obese children and adolescents without respiratory disease: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):281. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-01306-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Risnes K.R., Belanger K., Murk W., Bracken M.B. Antibiotic exposure by 6 months and asthma and allergy at 6 years: findings in a cohort of 1,401 US children. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(3):310–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wickens K., Ingham T., Epton M. The association of early life exposure to antibiotics and the development of asthma, eczema and atopy in a birth cohort: confounding or causality? Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(8):1318–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nafstad P., Jaakkola J.J., Hagen J.A., Botten G., Kongerud J. Breastfeeding, maternal smoking and lower respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(12):2623–2629. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dogaru C.M., Strippoli M.P.F., Spycher B.D. Breastfeeding and lung function at school age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(8):874–880. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1490OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oddy W.H., Holt P.G., Sly P.D. Association between breast feeding and asthma in 6 year old children: findings of a prospective birth cohort study. BMJ. 1999;319(7213):815–819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7213.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sears M.R., Greene J.M., Willan A.R. Long-term relation between breastfeeding and development of atopy and asthma in children and young adults: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2002;360(9337):901–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sears M.R., Greene J.M., Willan A.R. A longitudinal, population-based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(15):1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McGeachie M.J., Yates K.P., Zhou X. Patterns of growth and decline in lung function in persistent childhood asthma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):1842–1852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mathew A.R., Bhatt S.P., Colangelo L.A. Life-course smoking trajectories and risk for emphysema in middle age: the CARDIA lung study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;199(2):237–240. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201808-1568LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oelsner E.C., Balte P.P., Bhatt S.P. Lung function decline in former smokers and low-intensity current smokers: a secondary data analysis of the NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(1):34–44. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30276-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anthonisen N.R. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1: the Lung Health Study. JAMA. 1994;272(19):1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ley B., Collard H.R. Epidemiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:483–492. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S54815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Putman R.K., Hatabu H., Araki T. Association between interstitial lung abnormalities and all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2016;315(7):672–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhatta D.N., Glantz S.A. Association of e-cigarette use with respiratory disease among adults: a longitudinal analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(2):182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang M., Aaron C.P., Madrigano J. Association between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and change in quantitatively assessed emphysema and lung function. JAMA. 2019;322(6):546–556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Jong K., Vonk J.M., Zijlema W.L. Air pollution exposure is associated with restrictive ventilatory patterns. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(4):1221–1224. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00556-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Doiron D., de Hoogh K., Probst-Hensch N. Air pollution, lung function and COPD: results from the population-based UK Biobank study. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(1):1802140. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02140-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adam M., Schikowski T., Carsin A.E. Adult lung function and long-term air pollution exposure: ESCAPE—a multicentre cohort study and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(1):38–50. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00130014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Madrigano J., Baccarelli A., Wright R.O. Air pollution, obesity, genes, and cellular adhesion molecules. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(5):312–317. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.046193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Johnston R.A., Theman T.A., Lu F.L., Terry R.D., Williams E.S., Shore S.A. Diet-induced obesity causes innate airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine and enhances ozone-induced pulmonary inflammation. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(6):1727–1735. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00075.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou Y., Wang C., Yao W. COPD in Chinese nonsmokers. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(3):509–518. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00084408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kurmi O.P., Semple S., Simkhada P., Smith W.C.S., Ayres J.G. COPD and chronic bronchitis risk of indoor air pollution from solid fuel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2010;65(3):221–228. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.124644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.da Silva L.F.F., Saldiva S.R.D.M., Saldiva P.H.N., Dolhnikoff M. Impaired lung function in individuals chronically exposed to biomass combustion. Environ Res. 2012;112:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Taskar V.S., Coultas D.B. Is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis an environmental disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3(4):293–298. doi: 10.1513/pats.200512-131TK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Taskar V., Coultas D. Exposures and idiopathic lung disease. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29(6):670–679. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1101277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Peters U., Suratt B.T., Bates J.H.T., Dixon A.E. Beyond BMI: obesity and lung disease. Chest. 2018;153(3):702–709. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Salome C.M., King G.G., Berend N. Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J Appl Physiol. 2009;108(1):206–211. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00694.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thyagarajan B., Jacobs D.R., Apostol G.G. Longitudinal association of body mass index with lung function: the CARDIA study. Respir Res. 2008;9(1):31. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sun Y.Q., Brumpton B.M., Langhammer A., Chen Y., Kvaløy K., Mai X.M. Adiposity and asthma in adults: a bidirectional Mendelian randomisation analysis of the HUNT study. Thorax. 2020;75(3):202–208. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xu S., Gilliland F.D., Conti D.V. Elucidation of causal direction between asthma and obesity: a bi-directional Mendelian randomization study. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(3):899–907. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Benck L.R., Cuttica M.J., Colangelo L.A. Association between cardiorespiratory fitness and lung health from young adulthood to middle age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(9):1236–1243. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2089OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Garcia-Aymerich J., Lange P., Benet M., Schnohr P., Antó J.M. Regular physical activity modifies smoking-related lung function decline and reduces risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(5):458–463. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-896OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McEvoy C.T., Milner K.F., Scherman A.J. Vitamin C to Decrease the Effects of Smoking in Pregnancy on Infant Lung Function (VCSIP): rationale, design, and methods of a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy for the primary prevention of effects of in utero tobacco smoke exposure on infant lung function and respiratory health. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;58:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Martineau A.R., Jolliffe D.A., Hooper R.L. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Agustí A., Hogg J.C. Update on the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1248–1256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1900475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Regan E.A., Lynch D.A., Curran-Everett D. Clinical and radiologic disease in smokers with normal spirometry. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1539–1549. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kalhan R., Tran B.T., Colangelo L.A. Systemic inflammation in young adults is associated with abnormal lung function in middle age. PLoS One. 2010;5(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thyagarajan B., Smith L.J., Barr R.G. Association of circulating adhesion molecules with lung function: the CARDIA study. Chest. 2009;135(6):1481–1487. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McGroder C.F., Aaron C.P., Bielinski S.J. Circulating adhesion molecules and subclinical interstitial lung disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(3):1900295. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00295-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.King T.E., Pardo A., Selman M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 2011;378(9807):1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Armstrong H.F., Podolanczuk A.J., Barr R.G. Serum matrix metalloproteinase-7, respiratory symptoms, and mortality in community-dwelling adults: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(10):1311–1317. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0254OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rosas I.O., Richards T.J., Konishi K. MMP1 and MMP7 as potential peripheral blood biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Med. 2008;5(4):e93. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kalhan R., Dransfield M.T., Colangelo L.A. Respiratory symptoms in young adults and future lung disease: the CARDIA lung study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(12):1616–1624. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-2108OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stavem K., Sandvik L., Erikssen J. Breathlessness, phlegm and mortality: 26 years of follow-up in healthy middle-aged Norwegian men. J Intern Med. 2006;260(4):332–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Martinez C.H., Murray S., Barr R.G. Respiratory symptoms items from the COPD Assessment Test identify ever-smokers with preserved lung function at higher risk for poor respiratory outcomes: an analysis of the subpopulations and intermediate outcome measures in COPD study cohort. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(5):636–642. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-815OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Çolak Y., Nordestgaard B.G., Vestbo J., Lange P., Afzal S. Prognostic significance of chronic respiratory symptoms in individuals with normal spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(3):1900734. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00734-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Balte P.P., Chaves P.H.M., Couper D.J. Association of nonobstructive chronic bronchitis with respiratory health outcomes in adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):676–686. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rodriguez-Roisin R., Han M.K., Vestbo J., Wedzicha J.A., Woodruff P.G., Martinez F.J. Chronic respiratory symptoms with normal spirometry: a reliable clinical entity? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;195(1):17–22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201607-1376PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Oelsner E.C., Hoffman E.A., Folsom A.R. Association between emphysema-like lung on cardiac computed tomography and mortality in persons without airflow obstruction. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):863–873. doi: 10.7326/M13-2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hunninghake G.M., Hatabu H., Okajima Y. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2192–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1216076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Araki T., Putman R.K., Hatabu H. Development and progression of interstitial lung abnormalities in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(12):1514–1522. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2523OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hoyer N., Wille M.M.W., Thomsen L.H. Interstitial lung abnormalities are associated with increased mortality in smokers. Respir Med. 2018;136:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Podolanczuk A.J., Oelsner E.C., Barr R.G. High attenuation areas on chest computed tomography in community-dwelling adults: the MESA study. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(5):1442–1452. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00129-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Podolanczuk A.J., Oelsner E.C., Barr R.G. High-attenuation areas on chest computed tomography and clinical respiratory outcomes in community-dwelling adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(11):1434–1442. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0555OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]