Abstract

There has been little data published related to glucose control in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D) during lockdown, but rarely focusing on telemedicine’s role. During this unpreceded period, glucose control and self-monitoring improved in our young patients, with better results associated with telemedicine.

Keywords: COVID-19, Type 1 diabetes, Adolescent, Telemedicine, Continuous glucose monitoring

1. Introduction

A few reports focused on the impact of lockdown (resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic) on adolescents and young people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) [1]. We aimed to measure glucose control changes through the first French lockdown, focusing on telemedicine’s role.

2. Methods

All patients from 13 to 25 years old were included according to the following criteria: T1D diagnosed for more than one-year, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) connected to a LibreView account.

The primary outcome was the evolution of time-in-range (TIR): 70–180 mg/dL. Secondary outcomes were the evolution of glucose management indicator (GMI), time-below-range TBR (<70 mg/dL), and self-monitoring (sensor usage).

As the lockdown imposed by the French government occurred from March 17 to May 10, 2020, each outcome was assessed 4 times: the month before, the first month, the second month, and one month after lockdown ended.

Data were collected for patients from Sud-Francilien hospital and Kremlin-Bicêtre hospital (France) from the cloud-based platform, LibreView [2].

Data related to patients’ characteristics, treatment and telemedicine visits were collected from the medical record and confirmed with telephone-administered questionnaire.

Potential confounding factors were studied: age, gender, type of insulin delivery (multiple daily injections, MDI; insulin pump), contacts with health professionals (physician or nurse).

Descriptive statistics include means with standard deviations, numbers of patients and percentages. TIR evolution was analyzed with a linear mixed-effects regression model. Analyses of secondary outcomes paralleled the primary analysis. All models included adjustment for age, gender, type of insulin therapy, number of contacts with health professionals, and individuals (random effect). Effect of the number of contacts with health professionals during lockdown was assessed by including an interaction term in the models. Finally, a sensitive analysis was performed excluding all patients with a sensor usage of less than 70% at all times.

Analyses were performed with R studio version 3.5.0 [3].

All procedures were approved by a local ethics committee (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04669912).

3. Results

Seventy-seven patients with T1D were included. Mean age: 20.4 (2.8) years; mean duration of diabetes: 10.2 (5.4) years; 45% men; 61.0% were treated with an insulin pump. During the two months of lockdown, 25 (32.5%) patients had no health professional contact, 28 (36.4%) had 1–2 contacts and 21 (27.3%) had 3 or more contacts. This information could not be confirmed for 3 (3.9%) patients (no phone answer).

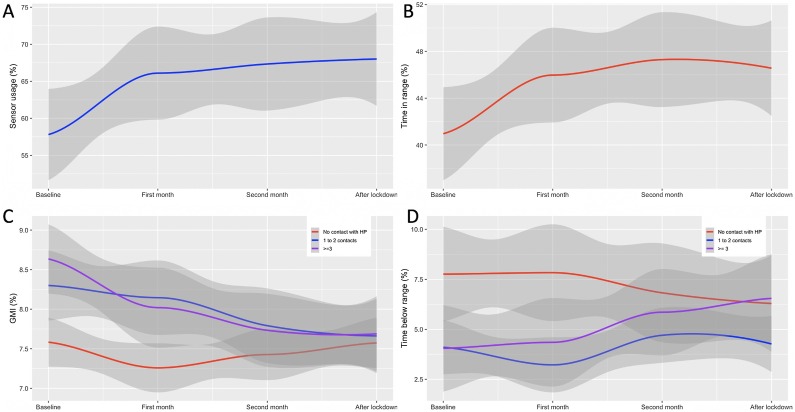

Evolution of primary and secondary outcomes are illustrated in Fig. 1 . At baseline (the month before lockdown), the mean percentage of TIR was 41.0% (15.8). The mean TIR significantly raised and was 41%, 46%, 47%, and 47% for the 4 consecutive months of observation (p < 0.001). At baseline, the mean GMI, TBR (<70 mg/dL), and percentage of sensor usage were respectively and 8.2% (1.1), 5.2% (4.5), and 57.8% (28.2).

Fig. 1.

Evolution of (a) glucose sensor usage (TIR), (b) time-in-range, (c) glucose management indicator (GMI), and (d) time-below-range (TBR) over the 4-month observation.

Baseline: month before lockdown; 1st month: first month of lockdown; 2nd month: second month of lockdown; after lockdown: first month after lockdown ended.

HP: health professional.Means of outcomes evolution are graphically represented with smoothing curves using local regression (LOESS).

Patients with 3 or more health professional contacts during lockdown had significantly lower TIR and higher GMI at baseline than patients with no healthcare professional contact.

The mean GMI significantly decreased (p < 0.001) and was 8.2%, 7.8%, 7.7%, and 7.7%; the mean percentage of TBR slightly increased (NS) and was 5.2%, 5%, 5.6%, and 5.5%; and the mean sensor usage significantly increased (p < 0.001) and was 58%, 66%, 67%, and 68%. Glucose coefficient of variation (CV) and time-above-range (>250 mg/dL) both decreased, from 43 (before lockdown) to 41 (after lockdown), and 53.8% to 48%, respectively.

Only the magnitude of GMI decrease and TBR increase were associated with the number of telemedicine visits (pinteraction respectively 0.004 and 0.002). No severe adverse event occurred (severe hypoglycemia or ketoacidosis requiring a medical intervention). Finally, the sensitive analysis excluding 16 patients with a percentage of sensor usage <70% at all times confirmed TIR improvement (rising from a mean of 43–50%, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion and conclusion

These findings support a significant improvement of glucose control and self-monitoring in a population of adolescents and young adults with T1D over the lockdown period in France. Moreover, results showed a greater improvement for patients with poor glycemic control at baseline. Patients with the lowest TIR and the highest GMI at baseline were those most actively supported by the healthcare professionals who were able to adapt to this unprecedented situation.

In contrast to Dalmazi et al. [1], the population we selected had a low glycemic control and sensor-usage at baseline, which probably explains the difference in results.

Spending lockdown at home probably led to a more regular lifestyle and more ambitious glycemic control goals. Also, due to limited outings and more family time, we assume a more balanced diet with a significant decrease in “junk food” consumption like it was shown by Ruiz-Roso et al. [4]. Finally, the significant raise in sensor usage probably reflects awareness improvement as sensor usage has been demonstrated to be positively associated with glycemic control [5,6].

The main limitation of this observational study is the population selection only included patients using a CGM related to Libreview. Moreover, we did not exclude patients with a low sensor usage because this would have led to a much smaller and higher selected sample as it has been shown that the level of self-monitoring does not meet guidelines in this young population [7]. However, the sensitive analysis is consistent with the results of the primary analysis.

Our results highlight the potential benefit of telemedicine in these young patients. In a randomized study, Ruiz de Adana et al. found out similar efficacy and safety outcomes comparing telemedicine to face-to-face visits [8]. Adolescents and young adults are a specific population, with a poor adherence to face-to-face visits (regularly missed). Remote visits, at the request of patients, may be the solution. Therefore, a similar randomized study comparing face-to-face and telemedicine visits in this specific population would be of great interest.

Contribution statement

C.S., K.L.S. and J.E. collected the data. C.A. analyzed the data. C.S. and C.A. wrote the first draft. Finally, all authors wrote and contributed to the interpretation of the data, revised critically each versions of draft, and globally participated to the whole aspect of the work. C.A. and A.P. take full responsibility for the work as a whole, including access to data, and the decision to submit and publish the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Dual of interest

The authors do not declare any dual of interest related to this study.

References

- 1.Dalmazi G.D., Maltoni G., Bongiorno C., Tucci L., Natale V.D., Moscatiello S. Comparison of the effects of lockdown due to COVID-19 on glucose patterns among children, adolescents, and adults with type 1 diabetes: CGM study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2020;8(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.More information available at: https://www.freestylelibre.co.uk/libre/products/libreview.html.

- 3.R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2020. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz-Roso M.B., de Carvalho Padilha P., Mantilla-Escalante D.C., Ulloa N., Brun P., Acevedo-Correa D. Covid-19 confinement and changes of adolescent’s dietary trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. Nutrients. 2020;12(6) doi: 10.3390/nu12061807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolinder J., Antuna R., Geelhoed-Duijvestijn P., Kröger J., Weitgasser R. Novel glucose-sensing technology and hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, non-masked, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2254–2263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell F.M., Murphy N.P., Stewart C., Biester T., Kordonouri O. Outcomes of using flash glucose monitoring technology by children and young people with type 1 diabetes in a single arm study. Pediatr. Diabetes. 2018;19(7):1294–1301. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood J.R., Miller K.M., Maahs D.M., Beck R.W., DiMeglio L.A., Libman I.M. Most youth with type 1 diabetes in the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry do not meet American Diabetes Association or International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes clinical guidelines. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):2035–2037. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz de Adana M.S., Alhambra-Expósito M.R., Muñoz-Garach A., Gonzalez-Molero I., Colomo N., Torres-Barea I. Randomized study to evaluate the impact of telemedicine care in patients with type 1 diabetes with multiple doses of insulin and suboptimal HbA1c in Andalusia (Spain): PLATEDIAN study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(2):337–342. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]