Key Points

Question

What risk factors and mechanisms can help explain documented allergic reactions to Food and Drug Administration–authorized mRNA COVID-19 vaccines?

Findings

In this case series of 22 patients with suspected vaccine allergy receiving clinical skin prick testing (SPT) and basophil activation testing (BAT) to the whole vaccine and key components (ie, polyethylene glycol [PEG] and polysorbate 80), none exhibited immunoglobulin (Ig) E–mediated allergy to components via SPT. However, most had positive BAT results to PEG, and all had positive BAT results to their administered mRNA vaccine, with no patient sample having detectable PEG IgE.

Meaning

These findings suggest that non–IgE-mediated allergic reactions to PEG may be responsible for many documented cases of allergy to mRNA vaccines.

This case series characterizes the immunologic mechanisms underlying allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

Abstract

Importance

As of May 2021, more than 32 million cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed in the United States, resulting in more than 615 000 deaths. Anaphylactic reactions associated with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–authorized mRNA COVID-19 vaccines have been reported.

Objective

To characterize the immunologic mechanisms underlying allergic reactions to these vaccines.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This case series included 22 patients with suspected allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines between December 18, 2020, and January 27, 2021, at a large regional health care network. Participants were individuals who received at least 1 of the following International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision anaphylaxis codes: T78.2XXA, T80.52XA, T78.2XXD, or E949.9, with documentation of COVID-19 vaccination. Suspected allergy cases were identified and invited for follow-up allergy testing.

Exposures

FDA-authorized mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Allergic reactions were graded using standard definitions, including Brighton criteria. Skin prick testing was conducted to polyethylene glycol (PEG) and polysorbate 80 (P80). Histamine (1 mg/mL) and filtered saline (negative control) were used for internal validation. Basophil activation testing after stimulation for 30 minutes at 37 °C was also conducted. Concentrations of immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgE antibodies to PEG were obtained to determine possible mechanisms.

Results

Of 22 patients (20 [91%] women; mean [SD] age, 40.9 [10.3] years; 15 [68%] with clinical allergy history), 17 (77%) met Brighton anaphylaxis criteria. All reactions fully resolved. Of patients who underwent skin prick tests, 0 of 11 tested positive to PEG, 0 of 11 tested positive to P80, and 1 of 10 (10%) tested positive to the same brand of mRNA vaccine used to vaccinate that individual. Among these same participants, 10 of 11 (91%) had positive basophil activation test results to PEG and 11 of 11 (100%) had positive basophil activation test results to their administered mRNA vaccine. No PEG IgE was detected; instead, PEG IgG was found in tested individuals who had an allergy to the vaccine.

Conclusions and Relevance

Based on this case series, women and those with a history of allergic reactions appear at have an elevated risk of mRNA vaccine allergy. Immunological testing suggests non–IgE-mediated immune responses to PEG may be responsible in most individuals.

Introduction

As of May 21, 2021, more than 32 million cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed in the United States, resulting in more than 615 000 deaths, which have disproportionately occurred in persons aged 65 years and older. Uncontrolled transmission of the SARS CoV-2 virus continues throughout the United States and in much of the world. The reemergence of novel, more easily and quickly transmissible variants (eg, B.1.1.7; 1.351; P.1) raise concerns about further spikes in cases and a greater ensuing public health burden.

In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted emergency use authorization to both Pfizer-BioNTech’s BNT162B2 mRNA and Moderna’s mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines. Subsequent safety analyses of Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) data between December 14, 2020, and January 18, 2021, estimated vaccine-related anaphylaxis events at rates of 4.7 and 2.5 cases per million doses for BNT162B2 and mRNA-1273, respectively.1 Of 66 confirmed anaphylaxis cases reported from 17 524 676 vaccine administrations, 95% occurred in women, and 79% and 32% of individuals with allergic reactions had a previous history of allergies and/or allergic reactions and anaphylaxis, respectively. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reviewed 3486 reports of death among individuals who had received the COVID-19 vaccinate and found “no evidence that vaccination contributed to patient deaths.”2

VAERS provides valuable insights into vaccine-induced anaphylaxis; however, it has limitations. Notably, VAERS is a passive reporting system requiring health care professionals to submit event reports that include vaccine lot numbers, which can be cumbersome to obtain and submit by treating clinicians. Additionally, the anaphylaxis case definition used by VAERS requires reactions to meet strict criteria, which can exclude mild reactions and some severe allergic reactions whose systemic involvement was limited by prompt treatment. Such treatment is more likely in health care workers who were overrepresented among the first wave of vaccinations, many of whom were vaccinated via occupational health programs in hospital settings. Hypervigilance toward adverse reactions to vaccines due to early publicized reports of vaccine-induced anaphylaxis and high rates of vaccine hesitancy may also lead to false-positive reports in VAERS. Given the high and growing prevalence of allergic disease in the general US population, public concern about possible vaccine-induced anaphylaxis risk among individuals with allergies, and the key role of vaccination in achieving herd immunity to COVID 19, it is essential that additional, comprehensive, and up-to-date clinical data be evaluated to further understand this important topic. Therefore, we hypothesized that life-threatening reactions to the vaccine are extremely rare and that most allergic reactions to vaccines are due to non–immunoglobulin (Ig) E–mediated pathways.3

As the global public health community expands vaccine access to include younger, more diverse populations who have historically exhibited higher rates of vaccine hesitancy,4 it is especially critical that we better understand the mechanisms underlying vaccine-induced anaphylaxis for risk stratification and improved anaphylaxis management as well as to inform further vaccine refinement. To those ends, this study provides clinical data, including skin prick tests (SPTs), basophil activation tests (BATs), and tryptase levels for a case series of vaccine-associated allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines from a large regional health system that was among the first in the United States to distribute these FDA-authorized vaccines.

Methods

This case series was designed to generate hypotheses and provide proof of concept, to recognize sentinel adverse events (allergic reactions and anaphylaxis), and to study the outcomes of new treatments (novel mRNA vaccines for COVID-19). Patient data were obtained from the Stanford Research Repository, which houses all clinical data at Stanford Medicine, including the Veterans Administration Palo Alto Hospital. Study activities were approved by the Stanford University institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent. This study followed the reporting guideline for case series.

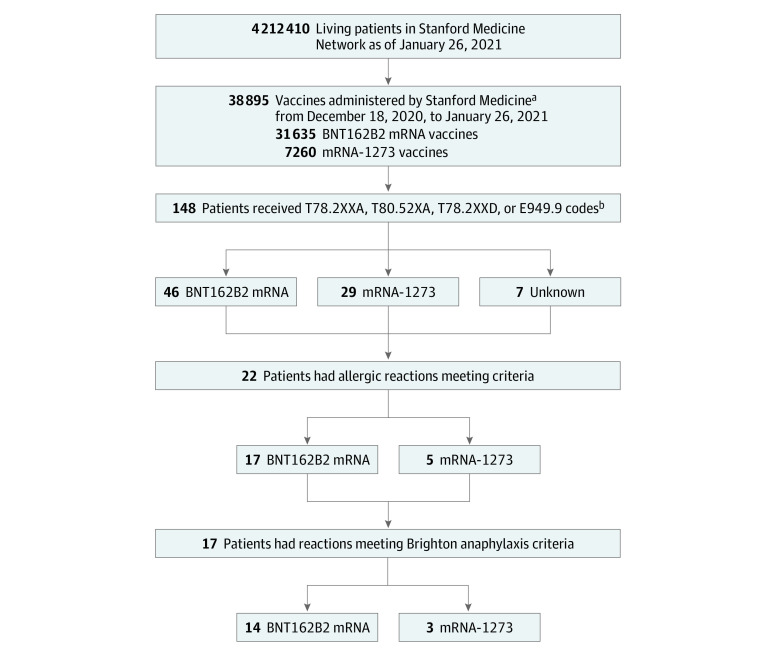

Based on multiple International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes and systematic medical record review of patients with COVID-19 vaccine–associated allergic reactions, we identified those meeting prespecified criteria for suspected allergy (Figure 1). Specifically, the following search criteria were used: any patient receiving at least 1 of the following ICD-10 anaphylaxis codes between December 18, 2020, and January 26, 2021: T78.2XXA (anaphylaxis, initial encounter), T80.52XA (anaphylactic reaction due to vaccination, initial encounter), T78.2XXD (anaphylaxis, subsequent encounter), or E949.9 (vaccine or biological substance causing adverse effect in therapeutic use). Of the 148 patients identified with 1 or more of these codes, 82 (55%) had a documented history of COVID-19 vaccination. Systematic medical record reviews of each patient identified 22 of 82 (27%) who met criteria for a possible allergic reaction. Allergic reactions were defined as those with symptoms starting within 3 hours of vaccination including hives; swelling of mouth, lips, tongue, or throat; shortness of breath, wheezing, or chest tightness; or changes in blood pressure or loss of consciousness. Reactions were graded by the authors using Brighton criteria.5

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

aNote that it is possible but not highly probable that some people received a COVID-19 dose outside Stanford Medicine during this time period. Most mRNA vaccine recipients during this time were Stanford-affiliated health care workers because public access to the vaccine was not authorized by the Santa Clara County Health Authorities for residents aged 65 years or older until January 26, 2021.

bT78.2XXA, anaphylaxis, initial encounter; T80.52XA, anaphylactic reaction due to vaccination, initial encounter; T78.2XXD, anaphylaxis, subsequent encounter; E949.9, vaccine or biological substance causing adverse effect in therapeutic use.

These individuals and their treating physicians were then contacted to invite the patient for clinical allergy follow-up testing. Each patient had been vaccinated through Stanford Medicine. Eight patients had previously received a clinical allergy workup, from which baseline tryptase levels were available. Tryptase levels were also available for these 8 patients within 2 hours after the allergic reaction and extracted from the patient’s medical record along with relevant medical history, demographic characteristics, and clinical atopic disease characteristics. Participant race and ethnicity was ascertained via medical record review and therefore, in most cases, can be assumed to result from patient self-report at clinical intake from a set of clinically defined response options. Race and ethnicity were assessed in this study to provide demographic information that may inform patient risk stratification and/or future targeted health education efforts. All participants were invited for follow-up SPT and BAT to the vaccine and relevant components, specifically polyethylene glycol (PEG) and polysorbate 80 (P80).

SPT

Single-lancet technique was performed with DMG-PEG 2000 (Avanti Polar Lipids, 1 μg/μL) or P80 (Millipore Sigma; Sigma Aldrich, 1 μg/μL). Histamine (1 mg/mL) and filtered saline (negative control) were used for internal validation. Antihistamine medication was withheld for at least 72 hours prior to the test. Wheal and erythema were measured at 15 minutes. The wheal and erythema measurements were recorded by taking the mean of the 2 perpendicular diameters in millimeters. A wheal size of 4 mm or greater was considered positive. Saline controls were used, and all were negative. Discarded, undiluted remnant vaccine was used according to the manufacturer’s concentration instructions.

BAT

Whole blood preserved in heparin, as described in Mukai et al,6 was collected from participants. Briefly, basophil activation was assessed after stimulation for 30 minutes at 37 °C with either DMG-PEG 2000 (Avanti Polar Lipids; 1 μg/μL) or P80 (Millipore Sigma–Sigma Aldrich; 1 μg/μL). Filtered saline was used as a negative control and anti-IgE (Bethyl Laboratories; 1 μg/mL) was used as a positive control.

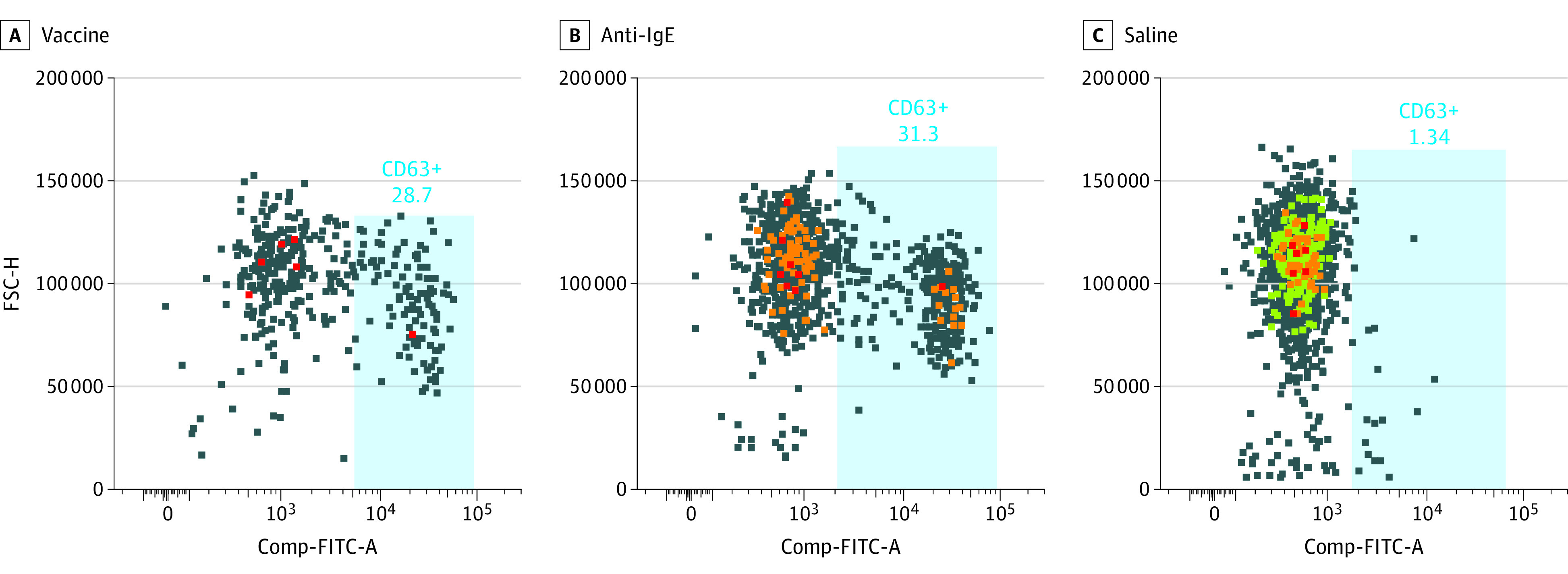

Vaccine-discarded remnant material was used at 0.007 μg/μL. All stimuli were prepared in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium. Basophils were gated as CD123+HLA−DR− cells, and the percentage of CD63+ basophils was quantified by flow cytometry. Control participants were also consented using the same IRB-approved protocol, and SPT and BAT assays were performed (Table 1). Figure 2 illustrates an example of BAT results among control participants using anti-IgE (positive control), saline, and vaccine material as an activator.

Table 1. Characteristics of Documented Cases of 17 Systemic Allergic Reactions, 5 Allergic Reactions, and 3 Control Participants to mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines Administered at Stanford Hospital Between December 18, 2020, and January 26, 2021a.

| Age, y | Sex | Race and ethnicity | History of allergies | History of anaphylaxis | Time to onset, min | Signs and symptoms during the initial reaction | Medications received | Code type | Skin test | Brighton level | Tryptase level, ng/mL | BAT | PEG IgE levels, ng/mL | PEG IgG levels, ng/mL | Time from first dose to blood draw, d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Documented cases of systemic allergic reactions and allergic reactions | |||||||||||||||

| 20-29 | F | White, non-Hispanic | No | No | 10 | Nausea, tongue edema | Acetaminophen, dexamethasone, epinephrine, famotidine, loratadine | Emergency | NA | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 30-39b | F | Other, Hispanicc | Drug, food | Yes | 1 | Chest pain, fatigue, headache, heart palpitations | Diphenhydramine, epinephrine, fluticasone propionate | Outpatient | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 1 | NA | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 679.9 | 38 |

| 50-59 | F | Black, non-Hispanic | No | No | 5 | Abdominal pain, dyspnea, hypotension, localized erythema, lightheadedness, presyncope, throat and chest tightness, tachycardia, airway swelling | Albuterol, diphenhydramine, epinephrine, famotidine, methylprednisolone | Emergency | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 1 | Baseline, 6; after reaction, 25 | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | <Cutoff | 35 |

| 40-49 | F | Asian, non-Hispanic | Drug, food, latex | Drug, food | 10 | Cough, cyanosis, generalized pruritus, localized urticaria, tachypnea | Albuterol, dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, epinephrine, famotidine, naloxone, ondansetron, potassium chloride | Emergency | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 2 | Baseline, 4; after reaction, 16 | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 349.02 | 76 |

| 50-59 | F | Other, non-Hispanicc | Drug | Drug | 10 | Dizziness, shortness of breath, stridor | Dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, famotidine, lidocaine, magnesium sulfate, morphine, ondansetron, PEG, prednisone | Emergency | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 2 | Baseline, 3; after reaction, 20 | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 805.02 | 44 |

| 20-29b | F | Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | Drug, food | No | 30 | Generalized pruritus | Cetirizine, diphenhydramine | Outpatient | NA | Skin allergy | Baseline, 5; after reaction: 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 30-39 | M | Asian, non-Hispanic | No | No | 20 | Generalized rash, generalized pruritus | Fluocinonide, loratadine triamcinolone acetonide | Outpatient | NA | Skin allergy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 30-39b | F | Other, non-Hispanicc | Drug | No | 5 | Dizziness, nausea, pharyngitis | Diphenhydramine, metoclopramide | Emergency | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 1 | NA | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 6903.24 | 14 |

| 30-39 | F | White, non-Hispanic | Drug | No | 150 | Throat swelling, throat itching, localized angioedema; symptoms more intense following second dose; symptoms recurred at skin test | Diphenhydramine | Emergency | Negative to PEG and P80; positive to vaccine | 2 | Baseline, 6; after reaction, 19 | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 1518.63 | 6 |

| 30-39 | F | Other, non-Hispanicc | Drug | No | 15 | Generalized erythema, face edema, ocular pruritus | Acetaminophen, diphenhydramine, epinephrine, famotidine, methylprednisolone | Emergency | NA | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 30-39 | F | Other, Hispanicc | No | No | 45 | Diaphoresis, generalized urticaria, lightheadedness, nausea | Diphenhydramine | Emergency | NA | 1 | Baseline, 2; after reaction, 16 | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 1097.98 | 32 |

| 30-39 | F | Asian, non-Hispanic | No | No | 120 | Generalized erythema, generalized pruritus | Diphenhydramine, famotidine, hydrocortisone | Emergency | NA | Skin allergy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 30-39 | F | White, non-Hispanic | Drug, food | No | 15 | Lightheadedness, localized erythema, localized urticaria, chest pain | Diphenhydramine, levothyroxine sodium | Emergency | NA | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 30-39 | F | Asian, non-Hispanic | Drug | No | 1 | Generalized pruritus, cough | None | Outpatient | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 2 | Baseline, 5; after reaction, 21 | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 667.56 | 78 |

| 40-49 | F | White, non-Hispanic | Food | No | 15 | Shortness of breath, flushed, rash, difficulty breathing | Epinephrine, prednisone | Emergency | NA | 1 | Baseline, 3; after reaction, 14 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 40-49 | F | Other, non-Hispanicc | Environmental, food | No | 120 | Headache, localized urticaria, wheezing | Fexofenadine hydrochloride | Outpatient | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 1 | NA | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 491.41 | 0 |

| 40-49 | M | Other, non-Hispanicc | No | No | 20 | Generalized erythema, generalized pruritus, generalized urticaria | NA | Emergency | NA | Skin allergy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 40-49b | F | Asian, non-Hispanic | Food | No | 15 | Generalized pruritus, headache, heart palpitations | Diphenhydramine | Emergency | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 1 | NA | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 2439.24 | 17 |

| 50-59b | F | White, non-Hispanic | Drug, food | Yes | 5 | Oral pruritus, localized erythema, throat tightness | Prednisone | Emergency | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 2 | NA | Positive to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | 679.07 | 57 |

| 50-59 | F | White, non-Hispanic | Drug | No | 2 | Dizziness, tachycardia, hypertension, cough | NA | Emergency | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | 2 | NA | Negative to PEG; positive to vaccine | <Cutoff | 1518.63 | 68 |

| 50-59 | F | Other, non-Hispanicc | No | No | 90 | Hypertension, shortness of breath, palpitations | Ondansetron | Emergency | NA | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 50-59 | F | White, non-Hispanic | Drug, food | Drug, food | 10 | Oral pruritus, rash | Diphenhydramine, famotidine, methylprednisolone | Emergency | NA | Skin allergy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Control Participants | |||||||||||||||

| 50-59 | F | White, non-Hispanic | Drug | Drug | None | None | None | NA | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | None | None | Negative to PEG and to vaccine | <Cutoff | <Cutoff | 0 |

| 50-59 | M | Hispanic | None | None | None | None | None | NA | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | None | None | Negative to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | <Cutoff | 31 |

| 20-29b | F | Hispanic | Food | Food | None | None | None | NA | Negative to PEG, P80, and vaccine | None | None | Negative to PEG and vaccine | <Cutoff | <Cutoff | 67 |

Abbreviations: BAT, basophil activation testing; Ig, immunoglobulin; NA, not available; P80, polysorbate 80; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

Allergic reactions were defined as those symptoms that started within 3 hours of vaccination and included hives; swelling of mouth, lips, tongue, or throat; shortness of breath, wheezing, or chest tightness; or changes in blood pressure or loss of consciousness. Reactions were graded using Brighton criteria5 for those with systemic anaphylaxis. Tryptase was obtained at baseline in some individuals and within 2 hours for postreaction levels. Specific IgE and IgG to PEG were conducted among participants who consented for a blood draw. The blood draw was used for both the BAT and Ig assays from the same visit for the participant.

Individual received mRNA-1273 vaccine.

Races coded as other in the electronic medical record retained this categorization. No listed races or ethnicities were recoded as other for the purpose of this study.

Figure 2. Basophil Activation Testing (BAT) Assay on Example Participant Using Vaccine, Anti–Immunoglobulin E (IgE), and Saline.

BAT assay on example participant with allergic reaction to the vaccine. Color indicates intensity of forward scatter and gated cells, with red being greater than orange; orange greater than green, and green greater than blue. FSC-H indicates forward side scatter-height; Comp-FITC-A, compensation–fluorescein isothiocyanate–area.

Anti–PEG-IgG and IgE Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays

Maxisorp 96-well microplates (NUNC) were coated with 5 μg/mL DSPE-PEG (2000) Biotin (Sigma Aldrich). After washing plates with 0.05% CHAPS (Sigma Aldrich) in PBS and blocking the wells with 2% BSA solution, the obtained plasma samples were incubated at 4 different dilutions (1:20, 1:40, 1:80, and 1:160). For the detection of specific PEG-IgG antibodies, alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat anti–human IgG (Thermo Fisher) was added at 1:2000 dilution. Specific PEG-IgE antibodies were detected by incubating samples first with a 1:3000 dilution of a mouse anti–human IgE followed by adding an alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG (Thermo Fisher) antibody at 1:2000 dilution. After a final wash step, substrate buffer containing 1.5 mg/mL nitrophenylphosphate (NPP, Sigma Aldrich) was added, and plates were read at a wavelength of 405 nm on a microplate reader (Berthold Mithras LB940). Specific IgG and IgE antibodies to PEG concentrations of each plasma were interpolated from a standard curve created with anti-PEG human IgG and anti-PEG human IgE, respectively (Academia Sinica, Taiwan). Minimum detections cutoffs were determined as OD405 0.2 and OD405 0.4 for PEG IgE and PEG IgG respectively; maximum detection cutoffs were determined as OD405 1.0 and OD405 1.9 for PEG IgE and PEG IgG respectively. High PEG IgG was considered for levels greater than OD405 1.5. The blood draw for the assays performed (both BAT and Ig levels) was done at the same visit for the each participant.

Statistical Analysis

No statistical testing was performed. R version 4.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing) was used to generate descriptive statistics.

Results

Between December 18, 2020, and January 26, 2021, Stanford Medicine administered 33 761 COVID-19 vaccine doses to health care workers and 5134 doses to local community members aged older than 65 years. Based on demographic information within the Stanford Research Repository, which was populated from patients’ electronic medical records, this population of vaccinated individuals was estimated to be approximately 60% women; 64% White, 2% Black, and 20% Asian; 16% younger than 50 years and 54% aged 70 years and older. These 38 895 patients are a subset of the 4 212 410 living patients present within the Stanford Research Repository during the study period. From this population, we identified 22 patients (20 [91%] women) meeting vaccine-related allergic reaction criteria (Table 1), of whom 17 (77%) received ICD-10 anaphylaxis codes in the emergency setting, with the remainder receiving these codes in an outpatient setting. Of the 22 patients, who ranged in age from 26 to 58 years with a mean (SD) age of 40.9 (10.3) years, 15 (68%) had a physician-documented history of previous allergic reactions: 10 (45%) to antibiotics, 9 (41%) to foods (including 3 [14%] to fruit, 2 [9%] to shrimp, 1 [5%] to peanuts, and 1 [5%] to porcine products). Eight patients (36%) had a history of allergy to medications besides antibiotics, including opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and local anesthesia (eg, lidocaine). Five patients (23%) had a history of anaphylaxis (3 [14%] to antibiotics, 1 [5%] to porcine products, and 1 [5%] to peanuts).

Of the 17 patients (77%) with mRNA vaccine-allergic reactions coded as likely anaphylaxis, each with Brighton level diagnostic certainty, 3 (14%) received epinephrine. All reactions fully resolved. Of patients who underwent SPTs, 0 of 11 tested positive to PEG; 0 of 11 tested positive to P80; and 1 of 10 (10%) tested positive to the same brand of mRNA vaccine used to vaccinate that individual. By contrast, among these same participants, 10 of 11 (91%) and 11 of 11 (100%) had positive BAT results to PEG and their administered mRNA vaccine, respectively (Figure 2). Three control participants underwent SPTs and BATs and showed typical baseline levels in control BAT assays.6,7,8 In Figure 2, an example BAT assay histogram is shown in which the blood of a participant who had an allergic reaction to the vaccine was incubated with vaccine, anti-IgE, and normal saline, and proportion of CD63 cells was determined (Figure 2). Table 2 reports summary findings from the BATs performed by condition and percentage of CD63+ of the gated basophil population in standardized whole blood BATs. Despite having an allergic reaction to the first, 1 patient received a second vaccine dose, which resulted in more severe symptoms. Although follow-up SPT with the same-brand vaccine material had negative results, her allergic symptoms returned with the SPT.

Table 2. Basophil Activation Testing With Each Condition and CD63+ of Gated Basophil Population in Standardized Whole Blood Basophil Activation Testing Assay.

| Overall responsea | Experiment | CD63+ frequency of basophil, % |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 38 |

| Saline | 2 | |

| PEG | 2 | |

| Vaccine | 2 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 2 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 24 |

| Saline | 3 | |

| PEG | 4 | |

| Vaccine | 11 | |

| Polysorbate | 2 | |

| Negative | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 17 |

| Saline | 4 | |

| PEG | 4 | |

| Vaccine | 4 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 4 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 31 |

| Saline | 1 | |

| PEG | 22 | |

| Vaccine | 29 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 3 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 36 |

| Saline | 4 | |

| PEG | 22 | |

| Vaccine | 21 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 4 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 38 |

| Saline | 4 | |

| PEG | 14 | |

| Vaccine | 39 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 4 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 41 |

| Saline | 6 | |

| PEG | 73 | |

| Vaccine | 67 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 5 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 11 |

| Saline | 4 | |

| PEG | 21 | |

| Vaccine | 23 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 5 | |

| Negative | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 16 |

| Saline | 5 | |

| PEG | 4 | |

| Vaccine | 4 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 5 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 15 |

| Saline | 2 | |

| PEG | 14 | |

| Vaccine | 12 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 3 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 24 |

| Saline | 3 | |

| PEG | 25 | |

| Vaccine | 23 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 3 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 23 |

| Saline | 3 | |

| PEG | 11 | |

| Vaccine | 9 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 4 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 25 |

| Saline | 2 | |

| PEG | 17 | |

| Vaccine | 74 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 3 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 74 |

| Saline | 3 | |

| PEG | 14 | |

| Vaccine | 15 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 4 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 42 |

| Saline | 6 | |

| PEG | 61 | |

| Vaccine | 56 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 5 | |

| Positive | Anti-IgE (positive control) | 77 |

| Saline | 2 | |

| PEG | 10 | |

| Vaccine | 13 | |

| Polysorbate 80 | 2 |

Abbreviations: Ig, immunoglobulin; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

A negative response was defined as less than 9% CD63+.

Because it is possible that the BATs were activated due to IgG (via complement activation–related pseudoallergy [CARPA]) or IgE (via IgE-FcεRec activation), we performed standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to measure IgE to PEG and IgG to PEG on collected blood samples. Given that some participants had limitations with scheduling appointments for blood draws during the COVID pandemic, sampling occurred between 0 to 78 days after the first dose of the vaccine, and high levels of IgG to PEG were detected during these periods. None of the individuals with an allergic reaction had IgE to PEG greater than the cutoff value.

Discussion

Currently, the CDC recommends that individuals with a history of allergic reaction to any mRNA COVID-19 vaccine component or who experienced a severe allergic reaction to the first dose not take either FDA-authorized mRNA vaccine.9 The published data to date suggest that vaccination may be specifically contraindicated among patients with allergic reactions to PEG and/or P80.9 The data presented here, collected from a large regional health center, suggest that allergic reactions from the mRNA vaccines are likely owing to PEG and non–IgE-mediated mechanisms, likely CARPA.

Of the stabilizing ingredients in the mRNA vaccine that we tested, P80 is a widely used emulsifier that can solubilize agents in foods and medicines, including vaccines.10 Previous work has found that this nonionic detergent can induce both local and systemic allergic reactions, including both IgE- and non–IgE-mediated anaphylaxis.11 The hydrophilic polymer known as PEG is structurally similar to P80.12 PEG and its derivatives are common ingredients in household products, including toothpaste, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and foods.13 In pharmaceuticals, PEG is often conjugated to biological therapeutics to form a depot agent, and sensitivity to PEG has been linked to IgE-mediated anaphylaxis after administration of PEG-conjugated biological therapeutics.9,10,14,15,16 Interestingly, severe allergic reactions to PEG have been associated with preexisting anti-PEG antibodies induced by PEG-containing household products,17 which may be more extensively used by women. Polysorbates are obtained from PEG moieties but have lower molecular weights and thus may be less allergenic.3 PEG may also be cross-reactive with polysorbates, which are present in some COVID-19 vaccines.18,19

However, measurements of preexisting anti-PEG antibodies vary widely, with a recent literature review reporting estimates ranging from 0.2% to 72% among healthy individuals.20 This is important because a high-molecular weight version of PEG is present in both of the FDA-authorized mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, where it helps to form a protective hydrophilic layer that sterically stabilizes the lipid nanoparticles.21 While further work is needed to clarify the causative role of PEG and/or P80 in the anaphylactic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines observed here and elsewhere, previous reports of similar reactions to other PEG-conjugated biologics suggest that PEG 2000 is likely to be an important causative agent that warrants further study.22,23,24

While allergy and/or anaphylaxis to FDA-authorized mRNA vaccines appear to be rare in all demographic groups, based on the present case series, women and those with a previous history of allergic reactions appear to have elevated risk. This is consistent with previous epidemiological data, which has found that approximately 85% of vaccine anaphylaxis cases had a history of prior allergic disease and that women are at a greater risk than men.25,26 Although our SPTs and BATs are research-based only, our data suggest a non–IgE-mediated immune pathway may be responsible for most reactions, possibly via complement activation through plasma immune complexes with the vaccine material or its components.5 This might explain the differences we observed between the SPT and whole blood BAT results, given that such PEG immune complexes likely exist in the blood more than the skin.

Future clinical trials in atopic populations—such as the ongoing National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease–supported phase 2 trial, Systemic Allergic Reactions to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination (NCT04761822)—will help to elucidate mechanisms, assist with guidelines to better assess vaccine allergy risk, and inform ongoing vaccine development, such as recently announced booster shots under development to protect against COVID-19 variants. Data suggest that patients who experience allergy to mRNA vaccines, as well as those who do not experience adverse effects after vaccination, still retain relative protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection.27,28 Given the demonstrated safety and real-world effectiveness of these mRNA vaccines,29 efforts to characterize and encourage reasoned consideration of the relative risks and benefits associated with COVID-19 vaccination among patients with higher risk of vaccine allergy can also help to advance mass vaccination campaigns, including ongoing efforts to address vaccine hesitancy. For example, when considering the risks associated with COVID-19 vaccination, it is important to note that an estimated 2% to 5% of the US population have experienced anaphylaxis, most commonly to medication, food, or insect stings.30 However, fatal anaphylaxis is exceedingly rare, with a recent review30 estimating an annual incidence of fatal drug-induced anaphylaxis at lower than death due to lightning strike in the general population. In contrast, COVID-19 has killed more than 615 000 US residents and made millions ill—some for many months, with a subset who may continue to experience long-term adverse health effects.31,32 Moreover, allergic reactions are highly treatable, and even severe anaphylaxis usually can be promptly mitigated with appropriate preparation and medication, as all patients in the present case series experienced; each of their allergic reactions resolved.

Limitations

This study has limitations. It is important to note that our data should not be generalized for the purposes of epidemiology of allergies to vaccines because this is a single-site study, evaluated over a limited time period, which did not incorporate a population-based sampling frame. Specific care should be taken when comparing these findings with previous reports of VAERS data1,2 given that the case definition used here was not intended only to identify severe allergic reactions but rather to identify cases of suspected mRNA vaccine allergy for mechanistic clinical follow-up.

Conclusions

In this study, women and those with a previous history of allergic reactions appeared to have a higher risk of developing mRNA vaccine allergy. SPT and BAT results to whole vaccine and PEG suggest a non–IgE-mediated immune response to PEG may be responsible. In the future, testing at baseline and longitudinal measurement of IgG PEG, BATs, and other molecules will be important to further test mechanisms. If confirmed by more systematic future investigations, these findings highlight potential opportunities for patient risk stratification and for alternatives in vaccine manufacturing; furthermore, they can inform ongoing mRNA vaccine development, including that of possible COVID-19 booster shots to protect against emerging disease variants.

References

- 1.Shimabukuro TT, Cole M, Su JR. Reports of anaphylaxis after receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in the US—December 14, 2020-January 18, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1101-1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Selected adverse events reported after COVID-19 vaccination. Updated August 2, 2021. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/adverse-events.html

- 3.Sampath V, Rabinowitz G, Shah M, et al. Vaccines and allergic reactions: the past, the current COVID-19 pandemic, and future perspectives. Allergy. 2021;76(6):1640-1660. doi: 10.1111/all.14840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan MS, Ali SAM, Adelaine A, Karan A. Rethinking vaccine hesitancy among minority groups. Lancet. 2021;397(10288):1863-1865. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00938-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rüggeberg JU, Gold MS, Bayas JM, et al. ; Brighton Collaboration Anaphylaxis Working Group . Anaphylaxis: case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2007;25(31):5675-5684. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukai K, Gaudenzio N, Gupta S, et al. Assessing basophil activation by using flow cytometry and mass cytometry in blood stored 24 hours before analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3):889-899.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appel MY, Nachshon L, Elizur A, Levy MB, Katz Y, Goldberg MR. Evaluation of the basophil activation test and skin prick testing for the diagnosis of sesame food allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018;48(8):1025-1034. doi: 10.1111/cea.13174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paranjape A, Tsai M, Mukai K, et al. Oral immunotherapy and basophil and mast cell reactivity in food allergy. Front Immunol. 2020;11:602660. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.602660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(7):643-649. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2035343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone CA Jr, Liu Y, Relling MV, et al. Immediate hypersensitivity to polyethylene glycols and polysorbates: more common than we have recognized. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(5):1533-1540.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calogiuri G, Foti C, Nettis E, Di Leo E, Macchia L, Vacca A. Polyethylene glycols and polysorbates: two still neglected ingredients causing true IgE-mediated reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2509-2510. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone CA Jr, Rukasin CRF, Beachkofsky TM, Phillips EJ. Immune-mediated adverse reactions to vaccines. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(12):2694-2706. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wenande E, Garvey LH. Immediate-type hypersensitivity to polyethylene glycols: a review. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46(7):907-922. doi: 10.1111/cea.12760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meller S, Gerber PA, Kislat A, et al. Allergic sensitization to pegylated interferon-α results in drug eruptions. Allergy. 2015;70(7):775-783. doi: 10.1111/all.12618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfaar O, Mahler V. Allergic reactions to COVID-19 vaccinations—unveiling the secret(s). Allergy. 2021;76(6):1621-1623. doi: 10.1111/all.14734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozma GT, Shimizu T, Ishida T, Szebeni J. Anti-PEG antibodies: properties, formation, testing and role in adverse immune reactions to PEGylated nano-biopharmaceuticals. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;154-155:163-175. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Povsic TJ, Lawrence MG, Lincoff AM, et al. ; REGULATE-PCI Investigators . Pre-existing anti-PEG antibodies are associated with severe immediate allergic reactions to pegnivacogin, a PEGylated aptamer. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(6):1712-1715. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerji A, Wickner PG, Saff R, et al. mRNA vaccines to prevent COVID-19 disease and reported allergic reactions: current evidence and suggested approach. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(4):1423-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badiu I, Geuna M, Heffler E, Rolla G. Hypersensitivity reaction to human papillomavirus vaccine due to polysorbate 80. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr0220125797. doi: 10.1136/bcr.02.2012.5797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong L, Wang Z, Wei X, Shi J, Li C. Antibodies against polyethylene glycol in human blood: a literature review. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2020;102:106678. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2020.106678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takayama R, Inoue Y, Murata I, Kanamoto I.. Characterization of nanoparticles using DSPE-PEG2000 and soluplus. Colloids Interfaces. 2020;4(3):28. doi: 10.3390/colloids4030028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruusgaard-Mouritsen MA, Johansen JD, Garvey LH. Clinical manifestations and impact on daily life of allergy to polyethylene glycol (PEG) in ten patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51(3):463-470. doi: 10.1111/cea.13822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cabanillas B, Akdis C, Novak N. Allergic reactions to the first COVID-19 vaccine: a potential role of Polyethylene glycol? Allergy. 2021;76(6):1617-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou ZH, Stone CA Jr, Jakubovic B, et al. Anti-PEG IgE in anaphylaxis associated with polyethylene glycol. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(4):1731-1733.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark S, Wei W, Rudders SA, Camargo CA Jr. Risk factors for severe anaphylaxis in patients receiving anaphylaxis treatment in US emergency departments and hospitals. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1125-1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNeil MM, Weintraub ES, Duffy J, et al. Risk of anaphylaxis after vaccination in children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(3):868-878. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. ; COVE Study Group . Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403-416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. ; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, et al. Interim estimates of vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among health care personnel, first responders, and other essential and frontline workers—Eight U.S. locations, December 2020-March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(13):495-500. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner PJ, Jerschow E, Umasunthar T, Lin R, Campbell DE, Boyle RJ. Fatal anaphylaxis: mortality rate and risk factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(5):1169-1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594(7862):259-264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-Month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):416-427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]