Abstract

Background

International and migrant students face specific challenges which may impact their mental health, well-being and academic outcomes, and these may be gendered experiences. The purpose of this scoping review was to map the literature on the challenges, coping responses and supportive interventions for international and migrant students in academic nursing programs in major host countries, with a gender lens.

Methods

We searched 10 databases to identify literature reporting on the challenges, coping responses and/or supportive interventions for international and migrant nursing students in college or university programs in Canada, the United-States, Australia, New Zealand or a European country. We included peer-reviewed research (any design), discussion papers and literature reviews. English, French and Spanish publications were considered and no time restrictions were applied. Drawing from existing frameworks, we critically assessed each paper and extracted information with a gender lens.

Results

One hundred fourteen publications were included. Overall the literature mostly focused on international students, and among migrants, migration history/status and length of time in country were not considered with regards to challenges, coping or interventions. Females and males, respectively, were included in 69 and 59% of studies with student participants, while those students who identify as other genders/sexual orientations were not named or identified in any of the research. Several papers suggest that foreign-born nursing students face challenges associated with different cultural roles, norms and expectations for men and women. Other challenges included perceived discrimination due to wearing a hijab and being a ‘foreign-born male nurse’, and in general nursing being viewed as a feminine, low-status profession. Only two strategies, accessing support from family and other student mothers, used by women to cope with challenges, were identified. Supportive interventions considering gender were limited; these included matching students with support services' personnel by sex, involving male family members in admission and orientation processes, and using patient simulation as a method to prepare students for care-provision of patients of the opposite-sex.

Conclusion

Future work in nursing higher education, especially regarding supportive interventions, needs to address the intersections of gender, gender identity/sexual orientation and foreign-born status, and also consider the complexity of migrant students’ contexts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-021-00678-0.

Keywords: International students, Nursing education, Foreign-born students, Migrant students, Gender, Gender identity, Coping responses, Supportive interventions, Scoping review, High-income countries

Background

In 2017, there were over 5 million international students worldwide (i.e., individuals pursuing educational activities in a country that is different than their country of residence) and this number is increasing annually [1]. This is largely due to a growing demand from students for higher education (college/vocational and university degrees) and the limited capacity in certain countries to meet this need. International experience is also highly valued by many employers and thus studying abroad makes new graduates more competitive in the workforce [2, 3]. On the pull-side, academic institutions are wanting to draw the most talented candidates and are looking to increase their student enrollment and revenues [2, 3]. Most international students are from Asia, in particular China, India, South Korea and Middle Eastern countries, while top destinations for these students are the US, the UK, France, Australia, Canada and Germany [3]. These same countries are also primary resettlement sites, and have substantial numbers of migrants (e.g., immigrants, refugees), especially from low and middle-income countries, enrolled in their colleges and universities [3–7]. This is driven by migrants who desire, or who are required to supplement their previous education in order to integrate into the local workforce, and by the expectations of many migrants for their children (including the 1.5 generation) to obtain an academic degree. Academic institutions in these major host countries are therefore needing to respond to and serve a more diverse student clientele.

Nursing is one of the many disciplines with an increasing number of foreign-born students. There are several benefits to the globalization of nursing education, including strengthening the healthcare workforce capacity (front-line workers, administrators, policy-makers, academics as well as researchers), increasing the linguistic and cultural diversity of nursing professionals, and the sharing of new ideas across countries toward the improvement of nursing practice [8, 9]. Increasing the level of education among nurses also improves health outcomes, enhances gender equality and contributes to economic growth, especially in low-and-middle-income countries [10, 11]. The course of study and clinical training in academic nursing programs however, are demanding and can affect the well-being of students and result in mental health problems [12–16]. Stress in turn can result in failure or students deciding to withdraw from their studies.

The stresses experienced by foreign-born nursing students are magnified due to factors related to their international/migrant status [17–20]. Challenges associated with living in a new country, including financial concerns, discrimination (perceived or actual), adapting to a new culture and language, loss of social support and unfamiliarity with the education, health and other systems, may affect education experiences and compound psychological distress. The challenges experienced and impacts may be patterned by gender. Gender is defined as the ‘socially constructed roles, behaviors, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for men, women, boys and girls’ [21]. The migration process itself is influenced by gender as the opportunity and the level of control over the decision to migrate typically differs between men and women. Fear of being persecuted because of one’s ‘gender identity’ (i.e., a person’s individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond to one’s biological sex) [22], may also be the reason one decides to migrate. Transit and post-migration experiences also diverge along gender lines, for example risks for gender-based violence, perceptions by the receiving-country society and integration outcomes often vary between male and female migrants and also by sexual orientation or gender identity (e.g., if one identifies as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and/or intersex) [23]. Moreover, international female students compared to male students, have reported facing greater expectations to balance home/childcare responsibilities [24, 25], experiencing more value conflicts regarding gender roles [26, 27], and having stronger emotional and physiological reactions to stress [28, 29]. In contrast, male students have expressed feeling stress associated with social status loss and due to traditional expectations to financially provide for the family, and they have been shown to be more likely to process their stress in solitude [30]. Gender norms can also affect both male and female students’ abilities to relate to members of the opposite sex in academic and clinical settings [27, 31]. To effectively support and promote the success of foreign-born nursing students, academic institutions should therefore ensure that approaches and resources not only take into account the foreign-born context, but also consider the gender dynamics that are shaping students’ experiences.

There is an extensive body of literature on foreign-born nursing students [17, 32–34], however, we did not identify any review that assessed the literature with a gender lens. Within the nursing education literature, reviews that have examined gender have primarily focused on the experiences of male students in general without any mention of a migrant or international background [35–39]; more recent reviews have considered the experiences of nursing students with diverse sexual and gender identities, although the research in this area remains scarce and also does not refer to foreign-born students [40–42]. In parallel, other literature has reviewed or discussed the intersection of gender or gender identity/sexual orientation and international status in relation to students’ experiences and its implications for academic institutions and educators, but none of these address the context of nursing or other healthcare professional education [43–45]. We therefore conducted a scoping review to address this gap. The objective of this scoping review was to map the literature on the challenges, coping responses and supportive interventions for international and migrant nursing students in academic institutions in major host countries with a gender lens.

Methods

A scoping review is commonly used to explore and summarize what is known on a particular topic [46]. This methodology was therefore selected since our goal was to describe what is known about gender and foreign-born nursing students’ experiences and supportive interventions across a broad array of existing literature while applying a gender lens. We used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews to guide our approach [46].

Search strategy

We consulted a university librarian to assist us in selecting the databases and in developing the search strategies. We searched 10 electronic databases including CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane, Medline, Web of Science, the Joanna-Briggs institute EBP database, Psych-Info, Eric, Sociological abstracts and ProQuest. Search terms (subject headings/descriptors, keywords) included those related to international and migrant students and to nursing education; the strategy was adapted for each database and the AND/OR Boolean operators were applied accordingly. Keywords were searched in the titles, abstracts, keywords and subject fields. No language or time restrictions were applied. In order to refine the searches and adjust them for the various platforms, we first conducted test searches in two databases (CINAHL and Medline). An example of one of the search strategies (CINAHL) is presented in Table 1. Additional papers were identified through the examination of the reference lists of literature review papers that met the inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

CINAHL search strategya

| 1 | (MH “Students, Nursing+”) OR (MH “Students, Nursing, Practical”) OR (MH “Education, Nursing+”) OR (MH “Schools, Nursing”) OR (MH “Faculty, Nursing”) |

| 2 | (MH “Faculty-Student Relations”) OR (MH “Education, Clinical+”) OR (MH “Learning Environment+”) |

| 3 | Nurs* |

| 4 | 2 AND 3 |

| 5 | (Nurs* N4 (student* OR education)) |

| 6 | 1 OR 4 OR 5 |

| 7 | (MH “Students, Foreign”) OR (MH “Transients and Migrants”) OR (MH “Emigration and Immigration”) OR (MH “Refugees”) OR (MH “Immigrants+”) OR (MH “English as a Second Language”) |

| 8 | “Born abroad” OR Foreign* OR Immigra* OR Refugee* OR Migra* OR ((International OR minorit*) N3 student*) OR ((Second OR additional OR proficiency OR native OR nonnative OR primary OR minorit* OR first) N3 language) OR (mother* N3 tongue) |

| 9 | 7 OR 8 |

| 10 | 6 AND 9 |

a Lines 3, 5 and 8, are keyword searches that were executed in the following fields: TI (title), AB (Abstract) and MW (Word in Subject Heading)

Literature selection

We included peer-reviewed research (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods), discussion papers and literature reviews. Study protocols, abstracts, books and dissertations/theses were excluded. English, French, and Spanish publications were considered. Literature was included if it discussed or reported on challenges, coping responses and/or supportive interventions for foreign-born students studying in an academic nursing program in Canada, the US, Australia, New Zealand or a European country (i.e., high-income countries according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that receive large numbers of migrants and international students and that have similar sociocultural norms and political systems) [47]. Challenges were defined as any difficulties experienced by the students; coping responses referred to any strategies that were used by the students to help overcome, minimize or tolerate challenges; while supportive interventions were policies, programs, or strategies meant to address challenges, enhance coping and improve students’ overall experiences. Challenges, coping and/or interventions could have been examined from the perspective of students and/or educators and administrators or could have just been described and discussed generally. Papers that reported on the evaluation or testing of an intervention were also included.

‘International students’ were defined as individuals with student visas but excluding exchange students and those completing only part of their degree abroad. ‘Migrant students’ were defined as individuals born in another country who moved with the intention of resettling in the new country; this includes immigrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers (i.e., individuals in the process of making a refugee claim) who could have migrated as children or as adults (second generation migrants were excluded). We included literature that focused on ‘English-as a second/additional-language’ (ESL/EAL) students without specifying the countries of origin, since foreign-born students often comprise a significant proportion of ESL/EAL students. Papers that focused on ‘minority’ or non-traditional nursing students were also kept if foreign-born or ESL/EAL students were clearly included and there were results and/or implications specific to this population. Similarly, if a paper included or discussed nursing students generally, it was retained if there were study results and/or implications relevant to foreign-born or ESL/EAL students. Literature that included internationally-trained nurses was considered if the nurses were studying in an academic nursing program; we excluded papers that examined internationally-trained nurses who were completing a transition/integration program.

Lastly, ‘Academic nursing program’ was defined as any program leading to a post-secondary degree including college/vocational, bachelor and graduate degrees in nursing. Papers that studied or discussed students from other healthcare disciplines were only kept if there were results and/or implications that referred to nursing students. Papers could have pertained to students in the context of clinical, theoretical and/or research education and training.

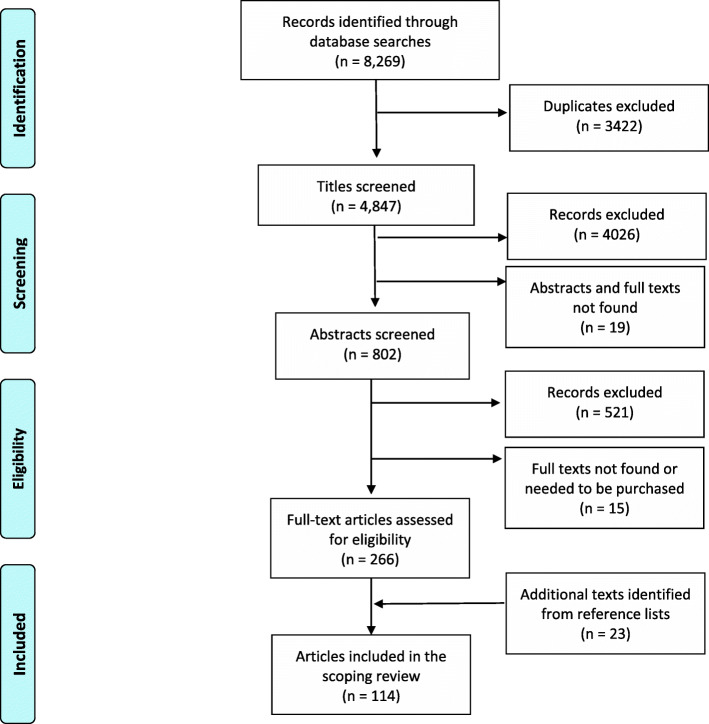

The database searches yielded 8269 records (see Additional file 1 for the search results by database). All citations were downloaded and managed using Endnote. We first removed duplicates and then screened titles to remove citations that clearly did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria. We then reviewed abstracts to further eliminate papers that did not meet all of the criteria. For the remaining citations we retrieved and reviewed the full-texts (n = 266) in order to confirm eligibility. The screening and selection process was led by KPV and supported by LM and BV via ongoing discussions to ensure that the criteria were being correctly and consistently applied. Articles at this step were mainly excluded because they did not have results and/or implications specific to foreign-born/ESL/EAL students or to nursing students (i.e., all healthcare professionals were examined and discussed together), or because they were theses/dissertations or descriptions of nursing programs that were intended to be advertisements to recruit new students. When there was uncertainty regarding the eligibility of an article, LM independently reviewed it and a decision on whether to include it was made through joint discussion with the other authors. Twenty-three additional papers were identified by examining the reference lists of included review papers. LM read all of the papers and confirmed the final selection (see Fig. 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine. 2009 Jul 21;6 (7):e1000097

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

For all eligible papers, we extracted and stored data in an excel file including: 1) paper characteristics (publication type, year, and language); and 2) study/review/discussion paper information. For the latter this included the paper objective, the location(s) of the study/discussion/review, the foreign-born student population(s) of interest in the paper (international students and/or migrants and their countries/regions of origin and length of time in the country; for migrants we also sought information on immigration status), the educational context, whether or not the perspectives of educators and/or administrators were considered/discussed, and information on challenges, coping responses and supportive interventions. For studies, we also extracted information on the research design and data collection methods, and for reviews, we recorded the type of review conducted, the number and type of sources (e.g., articles, books), and the process used to identify sources.

To address the review objective, we critically assessed each paper and recorded information related to gender. To do this, we drew on existing frameworks used to conduct gender analyses in health research [48, 49] and LM and BV developed key questions to help guide the assessment. These included the following:

Was sex included or addressed by the authors/researchers?

Was gender explicitly considered by the authors/researchers through use of a framework or lens?

Was gender identity/sexual orientation included or addressed by the authors/researchers?

Was sex and/or gender considered as a variable in analyses?

Were findings and/or implications reported separately by sex and/or gender?

- Based on the results and/or discussion points of the papers:

- Did sex or gender (appear to) play a role in the challenges experienced by students? For example, at the intersection of sex and gender such as roles within the family, cultural/religious conventions that dictate how men and women should behave, differential access to resources, and experiences of discrimination.

- Did coping responses (appear to) differ by sex or gender?

- Did interventions (appear to) consider gender roles, norms and expectations?

- Did interventions (appear to) consider diversity in gender identities/sexual orientations?

KPV was responsible for extracting the paper characteristics and information; LM verified all data extraction. The assessment of papers for gender related information was conducted by two research assistants. To ensure consistency in the process, 20 papers were reviewed by both research assistants. LM independently assessed all papers. All information collected was collated and synthesized into summary tables and text.

Results

One hundred and fourteen articles were included in the scoping review. A summary of the literature is reported in Table 2. All of the papers were published in English, 12 were discussion papers, 20 were reviews and 82 were research studies. The publication period spanned 39 years (1981–2019) and just over a quarter of papers (n = 30, 26%) were published within the last 5 years. Two-thirds of the research were qualitative studies.

Table 2.

Summary of the literature

| # | 1st Author (year) | Objective | Methodologya/Discussion paper/Review typeb | Countryc | Foreign-born Students’ descriptiond | Methodse (or N/A) | Educational contextf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research | |||||||

| 1 | Abu-Arab (2015) [50] | To present and discuss the challenges faced by a group of clinical educators in teaching and assessing nursing students from culturally-and-linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds in Australian English-speaking hospitals. | Qualitative descriptive | Australia |

International students Migrants Creole, Mandarin, Khmer, Malay, French, Korean, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Swahili, Malayalam speaking |

8 clinical educators 19 students Questionnaire |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 2 | Abu-Saad (1981) [51] | To assess the difficulties foreign nursing students encounter in their adjustment to university nursing programs and to evaluate the mechanisms that facilitate their adaptation to university nursing programs. | Quantitative survey with open-ended questions | United States |

Foreign-born Asia, Latin America, North America, Middle East, Africa, Western Europe, Scandinavia, South Pacific |

82 students Questionnaire |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) Clinical |

| 3 | Abu-Saad (1982) [52] | To examine actual and potential factors that help Asian students adjust to the nursing program and to describe difficulties encountered. | Quantitative survey with open-ended questions | United States |

Foreign-born Asian |

Students (sample not specified) Questionnaire |

College/vocational Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) Clinical |

| 4 | Abu-Saad (1982) [53] | To examine actual and potential factors that help Middle Eastern students adjust to the nursing program and to describe difficulties encountered. | Quantitative survey with open-ended questions | United States |

Foreign-born Iran, Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Israel (Arab only) LOT: average of 4 years |

Students (sample not specified) Questionnaire |

Not specified |

| 5 | Abu-Saad (1982) [54] | To examine whether academic nursing programs in the United States meet foreign nursing students’ and their countries’ needs and expectations. | Quantitative survey with open-ended questions | United States |

Foreign-born Asia, Latin America, North America, Middle East, Africa, Western Europe, Scandinavia, South Pacific LOT: 64% < 6 years |

82 students Questionnaire |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) Clinical |

| 6 | Alexander (1991) [55] | To examine the concerns of international students as they face life in a new culture and struggle with a second language, to examine their coping methods and to identify ways that can facilitate their learning. | Ethnography | United States |

International students Africa, others not specified |

16 students Interviews |

Bachelor |

| 7 | Ali Zeilani (2011) [56] | To explore the doctoral study experiences of Jordanian students who completed their nursing doctoral degree in the United Kingdom. | Qualitative descriptive | United Kingdom |

International students Jordan |

16 students Interviews |

Graduate (Doctorate) |

| 8 | Bosher (2002) [57] | To report the findings of a needs analysis conducted to determine why many English-as-a-second language (ESL) students enrolled in the Associate of Science degree nursing program were not succeeding academically and to report on the development, implementation and evaluation of a course created to respond to students’ challenges. | Descriptive (qualitative and quantitative data) | United States |

Migrants Needs assessment: West Africa, East Africa, South East Asia, Caribbean, Former Soviet Union LOT: an average of 5 years Course participants: Liberia, Somalia, Ethiopia, Cameroon, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos (Hmong), Nepal (Tibetan), China, Haiti, Cuba, Russia, Ukraine, India, Morocco LOT: an average of 5 years; two students 20 or more years |

1 program director 5 faculty members 28 students (participated in the needs assessment) 18 students (participated in and evaluated the course) Interviews Questionnaires Observations |

College/vocational Clinical |

| 9 | Bosher (2008) [58] | To determine the effects of linguistic modification on ESL students’ comprehension of nursing course test items. | Qualitative descriptive | United States |

Migrants India (Tibetan), Malaysia (Malay), Laos (Hmong), Ethiopia (Amharic) LOT: 3–10 years |

5 students Interviews Group discussions |

Bachelor |

| 10 | Boughton (2010) [59] | To describe and report findings from an evaluation of a support program for CALD nursing students enrolled in a two-year accelerated Master of Nursing program in Sydney, Australia. | Qualitative descriptive | Australia |

Foreign-born Korea, Philippines, Tanzania, United States, Singapore, China, Laos, Romania, Nigeria, Kenya, Zimbabwe LOT: 1 week to 29 years |

13 students Interviews |

Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| 11 | Brown (2008) [60] | To describe the development, implementation and outcomes of a program to increase the retention and success of foreign-born students challenged with English as a second language at a historically Black university located in Virginia, United States. | Descriptive (qualitative and quantitative data) | United States |

Migrants Ghana, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Kenya; Philippines, Vietnam, Mexico, Panama, Caribbean LOT: most > 10 years, two students < 2 years |

22 students (provided input for program development) Faculty members (sample not specified) 26 students (outcome data) Focus group Questionnaire Group meetings Interviews Informal discussions University data |

College/vocational Bachelor Clinical |

| 12 | Cameron (1998) [61] | To report results from an extensive needs analysis for ESL-speaking graduate nursing students with a focus on skills required for school, clinical practice and interaction with a multicultural, socially stratified patient population. | Descriptive/Ethnographic | United States |

International students Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, Jordan |

16 students (completed tests) 4 division chairpersons in the School of Nursing Clinical preceptors, educators and students (participated in interviews and/or observations, sample not specified) Speaking proficiency test Observations Interviews |

Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| 13 | Campbell (2008) [62] | To test the effects of using enhanced language instructions to improve oral and written communication skills for students with limited language proficiency and standard form of instructions. | Pre-test post test | United States |

Migrants Chinese, Korean, Haitian, East Indian, Hispanic, Russian |

20 students Tests on oral and written performance |

College/vocational Clinical |

| 14 | Caputi (2006) [63] | To describe how faculty members explored the learning needs of their student population with English-as-an-additional- language (EAL) and offer practical suggestions to help other faculty members. | Qualitative descriptive | United States |

Migrants Poland, Romania, Mexico, China, Philippines LOT: 6–18 years |

7 students Conversation circles Observations |

College/vocational Clinical |

| 15 | Carty (1998) [64] | To describe the challenges and support strategies used for Saudi international students in an intensive bachelor of nursing program in Virginia, United States. | Qualitative descriptive | United States |

International students Saudi Arabia |

12 students Faculty members (sample not specified) Discussions Observations |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 16 | Carty (2002) [65] | To identify challenges and positive points regarding international nurses’ doctoral education experiences in American schools of nursing. | Descriptive (qualitative and quantitative data) | United States |

International students Survey: Taiwan, Thailand, Zimbabwe, Cameroon, Colombia, Iceland, Netherlands, Lebanon, Brazil, Gambia, Greece, Kenya, India, Liberia, Germany, Puerto Rico, Hong Kong, Switzerland, South Korea, China, Japan, Jordan, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jamaica Focus group: Thailand, Egypt, Saudi Arabia |

24 universities (presumably administrators and/or faculty completed surveys) 5 students Survey Focus group |

Graduate (Doctorate) |

| 17 | Carty (2007) [66] | To identify predictors of success of Saudi Arabian students enrolled in an accelerated baccalaureate program leading to a bachelor of science in nursing degree. | Descriptive correlational | United States |

International students Saudi Arabia |

34 students Student records Application forms |

Bachelor |

| 18 | Chiang (2009) [67] | To offer additional knowledge and insights regarding teaching and learning barriers encountered by international nursing students and those training them and to describe and report on the evaluation of a transition course developed to support international students at an Australian university’s school of nursing. | Qualitative descriptive | Australia | International students |

Students (sample not specified) Educators (sample not specified) Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 19 | Colling (1995) [68] | To describe the experiences of international students including how they learn about various nursing schools in the United States, the type of programs in which they enroll, and the barriers they encounter when they come to study and to identify strategies that schools of nursing use to manage the educational and cultural challenges that students face. | Quantitative descriptive | United States |

International students Across the schools of nursing: 49 different countries, 50% from Asia 83 students: Asia, western Europe, Canada, Australia, Middle East, Africa, Hispanic countries |

83 students 45 schools of nursing Questionnaires |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) |

| 20 | Crawford (2013) [69] | To report findings from the initial round of interviews of an action research study, in which the project intended to evaluate the English language support program; identify the needs/ perceptions of students in terms of learning needs; and develop appropriate teaching/learning strategies to be implemented. | Qualitative descriptive | Australia |

International students Migrants Philippines, Zimbabwe, China, Japan, Egypt, Bangladesh |

8 students Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 21 | DeBrew (2014) [70] | To describe nurse educators’ experiences where they struggled in their decision to fail or pass a student in clinical, including foreign students and other students with non-traditional backgrounds. | Qualitative descriptive | United States | Foreign-born |

24 educators Interviews |

College/vocational Bachelor Clinical |

| 22 | DeLuca (2005) [71] | To describe what it is like to be a Jordanian graduate student in nursing in the contexts of a new culture, university and realm of professional nursing. | Phenomenology | United States |

International students Jordan |

7 students Interviews Journals |

Graduate (Masters) |

| 23 | Donnell (2014) [72] | To examine the associations between English language ability, participation in a reading comprehension program and attrition rates of nursing students in Texas. | Correlational, secondary analysis | United States |

ESL students Black, Hispanic/Latino |

3258 students (529 were ESL students) Questionnaires |

College/vocational Bachelor |

| 24 | Donnelly (2009) [73] | To identify factors that influence EAL students’ academic performance from the perspectives of the instructors. | Qualitative descriptive | Canada | Migrants |

9 instructors Focus groups |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 25 | Donnelly (2009) [74] | To gain a greater understanding of how EAL nursing students cope with language barriers and cultural differences and to identify the factors that help or hinder them to succeed. | Mini-ethnography | Canada |

Migrants China, Korea, Japan, Romania, Ukraine, Hong Kong LOT: 2.5–10 years |

14 students Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 26 | Doutrich (2001) [75] | To describe the international educational experiences of Japanese nurses completing a masters’ or doctoral degree in the United States. | Phenomenology | United States |

International students Japan |

22 students Interviews |

Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) Clinical |

| 27 | Dudas (2018) [76] | To study EAL students’ experience in an accelerated second-degree baccalaureate nursing program. | Phenomenology | United States |

International students Migrants Korea, others unknown |

12 students Interviews Field-notes |

Bachelor |

| 28 | Dyson (2005) [77] | To understand the lived experiences of Zimbabwean nursing students and to suggest strategies for improving their educational management. | Life history study |

United Kingdom |

International students Zimbabwe |

9 students 1 nurse Interviews/narratives |

College/vocational Clinical |

| 29 | Englund (2019) [78] | To investigate the relationship between marginality and nontraditional student status in nursing students enrolled in a baccalaureate nursing program in Texas. | Correlational | United States | ESL students |

192 students (32 were ESL) Questionnaire |

Bachelor |

| 30 | Evans (2007) [79] | To investigate the educational experiences of international doctoral nursing students and their research supervisors. | Qualitative descriptive | United Kingdom |

International students East Asia, Middle East |

5 students 11 supervisors Questionnaire (open-ended questions) |

Graduate (Doctorate) |

| 31 | Evans (2011) [80] | To explore the international doctoral student journey; specifically, to investigate the learning experiences of international doctoral nursing students at different points in their journey and to identify best practice in supporting effective learning in this student group. | Qualitative descriptive | United Kingdom |

International students European Union, Middle East, East Asia, South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa |

17 students Interviews |

Graduate (Doctorate) |

| 32 | Fettig (2014) [81] | To explore the role of peer-group interactions in the socialization of non-traditional nursing students in a licensed practical nurses –to-associate registered nurse program in the Midwest, United States. | Qualitative descriptive | United States |

International students African countries |

10 students Interviews |

College/vocational Clinical |

| 33 | Gardner (2005) [82] | To gain a greater understanding of the factors that influence foreign-born students’ success in nursing school. | Case study | United States |

Foreign-born East Indian LOT: 5 years |

3 students Interviews Observations |

Bachelor |

| 34 | Gardner (2005) [83] | To describe ethnic and racial minority nursing students’ experiences while enrolled in a predominantly White nursing program. | Phenomenology | United States |

Foreign-born East Indian, Hispanic, Hmong (Laotian), Nigerian, Filipino, Nepalese, Vietnamese, Chinese LOT: at least 4 years |

15 students Interviews |

Bachelor |

| 35 | Gay (1993) [84] | To describe the international students attending a large school of nursing in the United States, their challenges (from the perspective of faculty members) and the strategies used for dealing with problems. | Case study | United States |

International students Finland, Iceland, Japan, Jordan, Korea, China, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, Thailand |

42 students Observations (by faculty) |

Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) |

| 36 | Gilligan (2012) [85] | To: [1] discover the specific needs of CALD students in the Master of Pharmacy, Joint Medical Program and Bachelor of Nursing programs in relation to language and cultural considerations and [2] delineate the attitudes of domestic students to the cultural issues experienced by their peers and patients. | Qualitative descriptive | Australia |

International students China, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, Philippines |

35 students (10 nursing students) Focus groups |

Bachelor |

| 37 | Gorman (1999) [86] | To describe the views and experiences of non-English speaking background nursing students and the faculty members who teach them at two Australian universities. | Qualitative descriptive | Australia |

Foreign-born Italy, Russia, Poland, Malawi, China, Iran, Romania, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malta, Vietnam |

17 students 14 faculty members Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 38 | Greenberg (2013) [87] | To evaluate the effectiveness of a faculty development program on faculty’s self-reported feelings of comfort when acting as an ESL support person, ability to identify their own cultural biases and assumptions, knowledge of barriers and challenges faced by ESL nursing students, and ability to apply the knowledge gained from the project to ESL group sessions. | Pre-test-post-test | United States | ESL students |

10 faculty members Questionnaires Observations |

College/vocational Clinical |

| 39 | Guhde (2003) [88] | To describe and present the evaluation of a tutoring program meant to help ESL students master the English language. | Case study | United States |

Foreign-born China |

1 student Observations Discussions An evaluation of the student’s ability to understand clinical information |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 40 | Harvey (2017) [89] | To explore adult international students’ experiences of leaving spouse and children for further education overseas. | Descriptive phenomenology | Australia |

International students India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Brunei, the Philippines, Taiwan, China LOT: 2 months- 6 years |

10 students Interviews |

Graduate (not specified) |

| 41 | Havery (2019) [90] | To investigate how clinical facilitators’ pedagogic practices in hospital settings enabled or constrained the learning of students for whom English was an additional language. | Ethnography | Australia |

International students Korea, Japan, Cambodia, Taiwan, China, India, Hong Kong, Nepal, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia |

21 students 3 clinical facilitators Observations Field-notes |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 42 | He (2012) [91] | To investigate Chinese international undergraduate nursing students’ acculturative stress and sense of coherence at an Australian university in Sydney. | Quantitative descriptive and correlational | Australia |

International students China |

119 students Questionnaires |

Bachelor |

| 43 | Jalili-Grenier (1997) [92] | To 1- determine nursing students’ perceptions of the learning activities which contribute the most to their knowledge and skills; 2- determine students’ perceptions of their learning difficulties; 3- compare the perceptions of ESL and non-ESL students; 4- determine nursing faculty perceptions of ESL students’ learning difficulties; 5- compare the perceptions of ESL students and faculty; and 6- identify needs for educational and/or supportive programs for faculty and students. | Quantitative descriptive | Canada |

International students Migrants 21 countries LOT: ages on arrival 1 to 29 years old |

179 students 24 faculty Questionnaires |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 44 | James (2018) [93] | To explore the lived experience of one ethnically diverse nursing student who speaks English as a second language. | Narrative inquiry | United States |

Immigrant India LOT: immigrated when she was 11 years old |

1 student Informal discussions |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| 45 | Jeong (2011) [94] | To explore the factors that impede or enhance the learning and teaching experiences of CALD students and academic and clinical staff respectively and to identify support structures/systems for students and staff. | Qualitative descriptive | Australia |

International students Students enrolled in program: China, South Korea, other countries Participants: China, Philippines, Botswana |

11 students 3 clinical facilitators 4 academic staff Focus groups interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 46 | Junious (2010) [95] | To describe the essence of stress and perceived faculty support as identified by foreign-born students enrolled in a generic baccalaureate degree nursing program. | Interpretive phenomenology with a quantitative component | United States |

International students Migrants Nigeria, Cameroon, China, India, Vietnam LOT: < 10 years |

10 students Focus groups Interviews Questionnaires |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 47 | Kayser-Jones (1982) [96] | To identify the facilitating factors that help European and Canadian nursing students’ adjustment to American culture and the university and to describe their learning experiences and difficulties encountered. |

Quantitative survey with open-ended questions (qualitative data from open-ended questions were the focus in this paper) |

United States |

Foreign-born Canada, Norway, Denmark, England, Germany |

Students (sample not specified) Questionnaire |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) Clinical |

| 48 | Kayser-Jones (1982) [97] | To discuss the concept of loneliness and its relationship to the education of foreign nursing students who study in the United States. | Quantitative survey with open-ended questions | United States |

International students Asian, Latin American, Canadian, Middle Eastern, African, European, Australian |

82 students. Questionnaire |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) |

| 49 | Keane (1993) [98] | To examine learning styles, learning and study strategies, and specific background variables (primary language, ethnic background and length of time in the United States) in a multicultural and linguistically diverse baccalaureate nursing student population. | Correlational | United States |

Foreign-born Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Liberia,Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Haiti, Barbados, Nicaragua, Philippines, Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, Europe, Columbia, Peru LOT: 1 to > 10 years |

112 students Questionnaires |

Bachelor |

| 50 | Kelton (2014) [99] | To describe the clinical coach role and present data collected including outcomes achieved when a clinical coach role was implemented to support and develop nursing practice for the marginal performer or ‘at risk’ student. | Quantitative descriptive | Australia |

International students ESL students |

188 students University student data (outcomes of coaching) |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 51 | Khawaja (2017) [100] | To examine the relationship between second language anxiety and international nursing student stress. | Correlational | Australia |

International students LOT: majority 1–3 years, some < 1 year, others > 3 years |

152 students Questionnaires |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 52 | King (2017) [101] | To explore the perceived effectiveness of standardized patients as a means to achieve academic success among EAL nursing students. | Qualitative descriptive | Canada |

ESL students Arabic, Tagalog, Malayalam, Bengali, Afrikaans, other languages- speaking |

35 students Focus groups |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 53 | Leki (2003) [102] | To describe a Chinese undergraduate student’s literacy experiences in her nursing major. | Case study | United States |

International students Migrants (participant seems to be an immigrant but paper overall pertains to immigrants and international students) China LOT: 5 years |

1 student Students’ professors (sample not specified) Interviews Observations Journals Students’ school documents (e.g., assignments) |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 54 | Lu (2012) [103] | To elicit clinical tutors’ views on the ways in which EAL nursing students had developed appropriate spoken English for the workplace. | Qualitative descriptive | New Zealand |

International students Migrants |

4 clinical tutors Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 55 | Malu (1998) [104] | To uncover the problems that impeded success for immigrant ESL nursing students. | Case study | United States |

Migrants Latin America (region of origin was only mentioned for one student) |

Students (sample not specified) Interviews University admission data Observations |

College/vocational Clinical |

| 56 | Markey (2019) [105] | To explore international student experiences while undertaking Master of Science postgraduate education far from home. | Qualitative descriptive | Ireland |

International students Asian |

11 students Interviews |

Graduate (Masters) |

| 57 | Mattila (2010) [106] | To describe international student nurses’ experiences of their clinical practice in the Finnish health care system. | Qualitative descriptive | Finland |

International students African, Asian |

14 students Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 58 | McDermott-Levy (2011) [107] | To describe the experience of female Omani nurses who came to the United States to earn their baccalaureate degree in nursing. | Descriptive phenomenology | United States |

International students Oman |

12 students Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 59 | Memmer (1991) [108] | To identify and describe the various approaches used in baccalaureate nursing programs in California to retain their ESL students. | Descriptive (included qualitative and quantitative data) | United States | Migrants |

21 nursing programs (data collected from directors or designees of the programs) Questionnaire |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 60 | Mikkonen (2017) [109] | To describe international and national students’ perceptions of their clinical learning environment and supervision, and explain the related background factors. | Cross-sectional | Finland |

International students Africa, Europe, Asia, North America, South America LOT: 1–33 years |

329 students (231 were international students) Questionnaire |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 61 | Mitchell (2017) [18] | To explore the learning and acculturating experiences of international nursing students studying within a school of nursing and midwifery at one Australian university. | Qualitative | Australia |

International students Chinese, others unknown |

17 students Interviews Field-notes |

Bachelor Graduate (not specified) Clinical |

| 62 | Muller (2015) [110] | To present a case study, including an evaluation of a school-based language development and support program for EAL students. | Case study | Australia |

International students Asian, others unknown |

Students (sample not specified) Faculty and staff (sample not specified) Student data (e.g., number who participated in program, number who accessed resources, fail rates) Faculty and staff feedback through various methods |

Bachelor Graduate (not specified) Clinical |

| 63 | Mulready-Shick (2013) [111] | To explore the experiences of students who identified as English language learners. | Interpretive phenomenology | United States |

Migrants Central America, South America, Africa LOT: came to reside in United States in adolescence or early adulthood |

14 students Interviews |

College/vocational |

| 64 | Newton (2018) [112] | To examine the experiences of registered nurses who supervise undergraduate international nursing students in the clinical setting. | Case study | Australia | International students |

6 clinical supervisors Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 65 | Oikarainen (2018) [113] | To describe mentors’ competence in mentoring CALD nursing students during clinical placement and identify the factors that affect mentoring. | Cross-sectional | Finland | Migrants |

576 clinical mentors Questionnaire |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 66 | Ooms (2013) [114] | To identify and describe available supports at two universities for non-traditional background students and to measure the students’ perceptions regarding the use and usefulness of these supports. | Cross-sectional with a qualitative component |

United Kingdom |

ESL students |

812 students Questionnaire |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 67 | Palmer (2019) [115] | To explore the lived experiences of graduate international nursing students enrolled in a graduate nursing program. | Descriptive phenomenology | United States |

International students Saudi Arabia, India |

12 students Interviews |

Graduate (Masters) |

| 68 | Rogan (2013) [116] | To describe and evaluate an innovation to assist ESL nursing students at an Australian university develop their clinical communication skills and practice readiness by providing online learning resources, using podcast and vodcast technology, that blend with classroom activities and facilitate flexible and independent learning. | Cross-sectional with a qualitative component | Australia |

ESL students Chinese, Korean, Nepalese, Vietnamese, Other |

558 students (254 were ESL students) Questionnaire |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 69 | Sailsman (2018) [117] | To explore the lived experience of ESL nursing students who are engaged in learning online in a Bachelor of nursing program. | Interpretive phenomenology | United States |

ESL students Spanish, African, Russian, French, Filipino (Tagalog) speaking countries |

10 students Interviews |

Bachelor |

| 70 | Salamonson (2010) [118] | To evaluate a brief, embedded academic support workshop as a strategy for improving academic writing skills in first-year nursing students with low-to-medium English language proficiency. | Randomized controlled design | Australia |

International students Migrants |

106 students Student assignment scores |

Bachelor |

| 71 | San Miguel (2006) [119] | To report on the design, delivery and evaluation of an innovative oral communication skills program (the ‘clinically speaking program’) for first year students from non-English speaking backgrounds in a Bachelor or nursing degree at an Australian university. | Descriptive (included qualitative and quantitative data) | United States |

Foreign-born China, Hong Kong, Korea, Vietnam LOT: arrived within the previous 4 years |

15 Students 3 clinical facilitators Survey Students’ clinical grades Focus groups Students’ and facilitators’ comments |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 72 | San Miguel (2009) [120] | To report on an evaluation of the long-term effects of a language program that aimed to improve students’ spoken communication on clinical placements. | Qualitative descriptive interpretive | United States |

International students China, Vietnam, Taiwan, Hong Kong |

10 students Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 73 | Sanner (2002) [121] | To explore the perceptions and experiences of international students in a baccalaureate nursing program. | Qualitative descriptive | United States |

International students Nigeria LOT: 5–20 years |

8 students Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 74 | Sanner (2008) [122] | To describe the experiences of ESL students in a baccalaureate nursing program to develop a better understanding of the reasons for their course failures. | Qualitative descriptive | United States |

Migrants Liberia, Philippines LOT: 13–24 years |

3 students Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 75 | Shakya (2000) [123] | To explore the experiences of a small number of ESL/international nursing students during one year of their studies at a large Australian university. | Hermeneutic phenomenology | Australia |

International students Migrants Vietnam, Ethiopia, Iran, Nepal, Philippines, South Africa LOT: 4 months to 10 years |

9 students Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 76 | Shaw (2015) [124] | To identify key learning and teaching issues and to implement and evaluate ‘group work’ as a teaching strategy to facilitate international nursing student learning. | Participatory action research (descriptive with quantitative and qualitative data) | Australia |

International students Middle-East, South East Asia, Europe, Canada, North America, South America |

12 students (planning phase) 14 teaching staff (planning phase) 108 students (31 were international students; evaluation survey) Interviews Questionnaire (also included open-ended questions) |

Bachelor |

| 77 | Starkey (2015) [125] | To explore the critical factors that influence faculty attitudes and perceptions of teaching ESL students. | Grounded theory | United States | ESL students |

16 educators Interviews Focus group |

College/vocational Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| 78 | Valen-Sendstad Skisland (2018) [126] | To shed light on practice supervisors’ experiences of supervising minority language nursing students in a hospital context. | Qualitative descriptive | Norway | Foreign-born |

10 Clinical supervisors Interviews |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 79 | Vardaman (2016) [127] | To describe the transitions and lived experiences of international nursing students in the United States. | Descriptive phenomenology | United States |

International students Vietnam, China, Nepal, South Korea, Colombia, St. Lucia, Rwanda, Nigeria LOT: 9 months to 5 years, average of 4.3 years |

10 students Interviews |

College/vocational Bachelor Clinical |

| 80 | Wang (1995) [128] | To describe the experience of Chinese nurses studying abroad. | Phenomenology |

United States |

International students Taiwan |

23 students Interviews |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) Clinical |

| 81 | Wang (2008) [129] | To describe the experiences of Taiwanese baccalaureate and graduate nursing students studying at Australian universities. | Qualitative descriptive | Australia |

International students Taiwan LOT: < 1 year to > 2 years |

21 students Interviews |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| 82 | Wolf (2019) [130] | To explore the experiences of Chinese nurses when completing a graduate nursing degree taught in English (as a second language) in the United States. | Case study (included qualitative and quantitative data) | United States |

International students China |

8 students Survey Interviews |

Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| Discussion papers | |||||||

| 83 | Abriam-Yago (1999) [131] | To discuss and present the Cummins Model as a framework for nursing faculty to develop educational support that meets the learning needs of ESL students. | Discussion paper | United States | Migrants | N/A |

Any program Clinical |

| 84 | Choi (2016) [132] | To provide an overview of the establishment and implementation of a proactive nursing support program purposely designed to address the challenges faced by EAL students. | Discussion paper | Canada | ESL students | N/A |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 85 | Coffey (2006) [133] | To describe a bachelor of Science in Nursing Bridging Program which aims to address barriers and provide access to employment for internationally educated nurses who are residents in Ontario, Canada. | Discussion paper | Canada | Migrants | N/A |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 86 | Colosimo (2006) [134] | To discuss how shame affects the learning and experiences of ESL students and present the implications for nursing education. | Discussion paper | United States |

International students Migrants |

N/A |

College/vocational Bachelor |

| 87 | Genovese (2015) [135] | To describe the current complexities associated with the process of admitting international students to graduate nursing programs and how to avoid some pitfalls. | Discussion paper | United States | International students | N/A |

Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) Clinical |

| 88 | Henderson (2016) [136] | To provide tips on how to support international students to overcome challenges while studying nursing in Australia. | Discussion paper | Australia | International students | N/A | Bachelor |

| 89 | Malu (2001) [137] | To propose six active learning-based teaching tips for faculty teaching ESL students. | Discussion paper | United States | Migrants | N/A |

College/vocational Bachelor Clinical |

| 90 | Robinson (2006) [138] | To describe the development and implementation of a partnership and program at an American university for foreign nurses from India to obtain graduate education. | Discussion paper | United States |

International students India |

N/A |

Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| 91 | Ryan (1998) [139] | To describe the challenges and strategies used in a program at an American university that provides nurses from Taiwan to obtain a bachelor of science degree in nursing. | Discussion paper | United States |

International students Taiwan |

N/A |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 92 | Shearer (1989) [140] | To provide suggestions for teachers who are presented with the challenge of teaching students that use English as a second language. | Discussion paper | United States | International students | N/A |

College/vocational Bachelor |

| 93 | Terada (2012) [9] | To describe the requirements for admission and the challenges that international and ESL students face while studying in advanced practice nursing programs in the United States. | Discussion paper | United States | International students | N/A |

Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| 94 | Thompson (2012) [141] | To explore cultural differences in communication and to identify strategies to improve the experience of international and ESL students studying in advanced practice nursing programs in the United States. | Discussion paper | United States | International students | N/A |

Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| Reviews | |||||||

| 95 | Burnard (2005) [142] | To review and discuss some of the research on problems associated with studying overseas and in a different culture and to provide suggestions on how teachers in universities might address these challenges. | Literature review | United Kingdom | Foreign-born |

17 sources (books, dissertation, chapters, online material) Medline, library searches and ‘serendipitous findings’ |

Any program |

| 96 | Choi (2005) [143] | To examine the challenges faced by ESL nursing students, and identify strategies and explore the utility of the Cummins model of English language acquisition in educating these students. Recommendations for educating ESL nurses are also made. | Literature review | Canada | ESL students |

12 articles Search strategy not specified |

College/vocational Bachelor Clinical |

| 97 | Crawford (2013) [19] | To discuss the challenges ESL nursing students face in adjusting to Western culture, their difficulties using academic English and technical language of healthcare, and the support programs for these students. | Literature review | Australia | ESL/international students |

33 sources (articles and books) Search strategy not specified |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| 98 | Davison (2013) [144] | To investigate the application of mobile technologies to support learning in a specific context, namely nursing education for ‘English as a foreign language’ learners. | Qualitative meta-synthesis | Canada | ESL students |

66 sources (articles and dissertations) Databases (ERIC, Education Research Complete, CINAHL) |

Not specified Clinical |

| 99 | Edgecombe (2013) [145] | To identify factors that may impact international nursing students’ clinical learning with a view to initiating further research on how to work with these students to enhance their learning. | Literature review | Australia | International students |

36 articles Databases (CINAHL, ERIC, PubMed, Medline, ProQuest Central, Biomed Central, Joanna Briggs, Cochrane databases, Google Scholar, Sci-Verse-Hub) |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 100 | Evans (2010) [146] | To review the literature on international doctoral students’ experiences, with specific reference to nursing. | Literature review | United Kingdom | International students |

19 sources (book chapter, research report, conference paper, journal articles) Databases (ERIC, CINAHL, PubMed, ASSIA) |

Graduate (Doctorate) |

| 101 | Gilchrist (2007) [37] | To discuss strategies for attracting and retaining students from diverse backgrounds, including ESL students in nursing education. | Literature review | United States | ESL students |

13 articles (other literature related to other student groups who face barriers in nursing education was also included) Search strategy not specified |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 102 | Greene (2012) [33] | To discuss the barriers to educational success among internationally born students and to propose practical, evidence-based strategies that nursing faculty can implement to help international students succeed in nursing school. | Literature review | United States |

International students Migrants |

31 sources (articles, books) Search strategy not specified |

College/vocational Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctoral) Clinical |

| 103 | Hansen (2012) [147] | To discuss areas of difficulty for ESL nursing students and to recommend strategies that can be employed by supportive faculty to assist these students. | Literature review | United States | ESL students |

35 sources (book chapters, articles) Search strategy not specified |

College/vocational Clinical |

| 104 | Koch (2015) [42] | To identify studies which describe the clinical placement experiences of nursing students who have a broad range of diversity characteristics. | Literature review | Australia |

International students Migrants |

6 articles (other literature related to other student groups who face barriers in nursing education was also included) Databases (CINAHL, PubMed, Academic Search Complete, Medline, Education Search Complete, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, Science Direct, Scopus, Google Scholar) and reference lists of potentially relevant studies |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 105 | Kraenzle Schneider (2019) [148] | To discuss the challenges of international doctoral nursing students and recommend strategies to support them. | Literature review | United States | International students |

17 articles Databases (CINAHL, Medline, PsychInfo, PubMed, Scopus) and ‘other search methods’ |

Graduate (Doctorate) |

| 106 | Lee (2019) [149] | To examine the effectiveness of programs to improve (clinical) placement outcomes of international students and to collate recommendations made by international students and/or placement supervisors that they felt might improve placement outcomes. | Systematic review | Australia | International students |

10 articles (other literature related to other disciplines was also included) Databases (PsychInfo, CINAHL Plus, ProQuest Central, ERIC, Informit A+ Education, Informit MAIS) and reference lists of included articles |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Clinical |

| 107 | Malecha (2012) [17] | To identify and summarize what have been reported as stressors to foreign-born nursing students living and studying in the United States. | Literature review | United States |

International students Migrants |

11 articles Databases (ERIC, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsychInfo, Web of Science) and reference lists |

College/vocational Bachelor Clinical |

| 108 | Mikkonen (2016) [20] | To describe the experiences of CALD healthcare students’ in a clinical environment. | Systematic review of qualitative studies | Finland |

International students Migrants |

12 articles Databases (CINAHL, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, Academic Search Premiere, ERIC, Cochrane library) and reference lists of included studies |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 109 | Newton (2016) [150] | To review the literature reporting on the experiences and perceptions of registered nurses who supervise international nursing students in the clinical and classroom setting. | Integrative literature review | Australia | International students |

10 articles Databases (CINAHL, Informit, PubMed, Medline, Journals@Ovid, Findit@flinders) |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 110 | Olson (2012) [34] | To identify the barriers and discover bridges to ESL nursing student success. | Literature review | United States |

International students Migrants |

25 articles Databases (Academic Search Premier, CINAHL, PubMed, DAI, ERIC) and reference lists from the first database run |

College/vocational Bachelor Clinical |

| 111 | Scheele (2011) [151] | To synthesize the existing literature on Asian ESL nursing students including their challenges encountered and academic strategies to help these students. | Systematic review | United States |

International students Migrants Asian |

15 articles Databases (CINAHL, LexisNexis, Expanded Academic ASAP plus, Medline, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PsychInfo) |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 112 | Starr (2009) [152] | To synthesize the current qualitative literature on challenges faced in nursing education for students with EAL. | Meta-ethnographic synthesis of qualitative literature | United States | Migrants |

10 articles Databases (CINAHL, ERIC, PubMed, EbscoHost, Medline) |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 113 | Terwijn (2012) [153] | To synthesize the existing literature on the experiences of international students in undergraduate nursing programs in English-speaking universities. | Systematic review | Australia | International students |

19 articles Databases (CINAHL, Medline, EBSCOHost, ERIC, PsychInfo, MedNar, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, Google Scholar + several others (n = 37 total)) and reference lists of suitable articles collected during the search process |

Bachelor Clinical |

| 114 | Wang (2015) [154] | To report the current knowledge on the Chinese nursing students’ learning at Australian universities. | Narrative literature review | Australia |

International students Chinese |

15 articles Databases (A+ Education, Australian Bureau of Statistics, CINAHL, ERIC, Medline, ProQuest), table of contents of 14 journals and reference lists of relevant articles |

Bachelor Graduate (Masters) Graduate (Doctorate) Clinical |

a The methodology is based on what was reported in the paper. If a general qualitative methodology was used, it is described as ‘Qualitative descriptive’

b The review type is based on what was reported in the paper. If no specific type of review was named, it is described as a ‘Literature review’

c For discussion papers, the country is based on the location that was the focus of interest in the discussion. For reviews, the country is based on the country where the first author is based (since almost all reviews included literature from multiple countries and did not focus on a specific country)

d For research papers that included student participants, the description of students indicates whether participants included international students and/or migrants; ‘foreign-born’ is indicated if it’s clear that foreign-born students were included but it’s unclear whether they were international students and/or migrants; ‘ESL students’ is indicated if it was not explicitly stated that foreign-born students were included in the study (and there was no explicit mention of international students and/or immigrant students). Country/region of origin or ethnic/language background and LOT (length of time) in country are indicated if information was available for these indicators. For research papers that included only educators and/or administrators as participants, discussion papers and reviews, the description of students is based on the focus of the paper – i.e., international students and/or migrants or foreign-born or ESL students; country/ethnic background is indicated if a specific group was examined

e For research papers, the methods include the sample (the number of student and/or educator/administrator participants) and the methods used to gather data. For reviews, the methods include the number and type of sources included in the review and the process used for identifying sources

f For research papers, the educational context is based on the degree level of the student participants and/or the degree level of the students who were supervised and educated by the educator participants. ‘College/vocational’ refers to a level of qualification that is between a high school diploma and a bachelor’s degree. For discussion papers and reviews, the educational context is based on the degree level that was the focus of interest in the paper or the degree level that the results pertain to. In all instances, ‘Clinical’ is indicated if the clinical context was examined or discussed in the paper

Focus of the research, discussion papers and reviews

Twenty-two of the research papers primarily focused on highlighting challenges faced by foreign-born students; nine of these included the perspectives of educators (Table 2). Seventeen research papers aimed to identify or examine coping responses and factors that facilitated success among foreign-born students, while 24 papers generally explored students’ and/or educators’ experiences. Twelve research articles described and reported the findings of evaluations of support programs, courses or other strategies meant to support foreign-born/ESL/EAL students and seven other papers were intervention studies (including qualitative and quantitative), which mostly sought to help students’ overcome learning difficulties due to language barriers.

The discussion papers and reviews had similar foci (Table 2). Three discussion papers provided tips on how educators and institutions can support foreign-born/ESL/EAL students, five discussed challenges, implications and strategies to address these, and four other papers described programs, frameworks or approaches to promote the success of students. Among the 20 review papers, all but three included a mix of qualitative, quantitative and other types of literature and only three specifically named the type of review being conducted. Most (n = 12) aimed to synthesize the literature on foreign-born/ESL/EAL students’ challenges and support strategies for these students, while five were reviews of the literature of foreign-born/ESL/EAL students’ general experiences, and two focused on interventions including mobile applications to support ESL students’ learning, and programs to improve clinical placement outcomes of international students.

Locations, educational contexts and populations

The majority of the research (57%) was conducted in the United States; four studies were conducted in non-English speaking countries (Norway and Finland) (Table 3). All but three of the discussion papers, and one review were also specific to the United States context. Several of the research papers pertained to more than one level of education; overall bachelor or college level studies were included in 90%, and graduate level education in 42%, of studies (Table 3). Four discussion papers were limited to bachelor level, four were focused on graduate level, and four others were relevant to nursing education in general. The literature reviews tended to be non-specific, however one and two papers respectively focused on bachelor and doctorate level education. The clinical learning environment was mentioned in two-thirds of the research papers, although was the primary focus in 18% of the research (Table 3). The clinical context was also the main focus in six of the reviews.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the research studies

| Descriptor | Papers N = 82, % (n) |

|---|---|

| Methodology | |

| Qualitativea | 67.1% (55) |

| Quantitativeb | 24.4% (20) |

| Mixed | 8.5% (7) |

| Location of the study | |

| United States | 57.3% (47) |

| Europec | 12.2% (10) |

| Australia | 24.4% (20) |

| Canada | 4.9% (4) |

| New Zealand | 1.2% (1) |

| Student groupd | |

| International students | 46.3% (38) |

| Migrants | 15.9% (13) |

| International students and migrants | 11.0% (9) |

| Foreign-born non-specified | 17.1% (14) |

| English-as-a-second language students | 9.8% (8) |

| Education leveld,e | |

| College/vocational | 17.1% (14) |

| Bachelor | 73.2% (60) |

| Masters | 22.0% (18) |

| Doctorate | 15.9% (13) |

| Graduate (not specified) | 3.7% (3) |

| Clinical learning environment was a primary focus | 18.3% (15) |

| Academic or clinical educator and/or administrator participants | 34.1% (28) |

| Student participants | 89.0% (73) |

| Student participants’ sex | N = 73f |

| Males | 2.7% (2) |

| Females | 12.3% (9) |

| Males and Females | 56.2% (41) |

| Not specified | 28.8% (21) |

| Student participants’ region of origine | N = 73f |

| North Africa and/or Middle East | 31.5% (23) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa/Africa unspecified and/or South Africa | 39.7% (29) |

| Caribbean | 8.2% (6) |

| Latin America | 21.9% (16) |

| Eastern Europe and/or Russia | 9.6% (7) |

| South Asia | 19.2% (14) |

| South East Asia | 39.7% (29) |

| East Asia | 45.2% (33) |

| Unspecified Asia | 26.0% (19) |

| Western/Northern/Southern Europe, North America | |

| (excluding Mexico), and/or Australia | 17.8% (13) |

| Unspecified | 26.0% (19) |

a Two also included some quantitative data

b Seven also included some qualitative data

c Includes the United Kingdom (n = 5), Finland (n = 3), Ireland (n = 1) and Norway (n = 1)

d Based on the student participants and/or the focus of the paper

e A study may be counted in more than one category so percentages do not add to 100%

f Based on studies with student participants

Across the literature students were described using different terms including ‘foreign-born’, ‘ESL’, ‘EAL’, ‘culturally-and-linguistically diverse (CALD)’, ‘international students’, ‘non-English-speaking background’, ‘immigrants’, and ‘minority or non-traditional students’; in other instances, students were described based on their ethnic background or origin. Length of time in the host country was generally not highlighted; just over a third (34%) of studies with student participants mentioned some information on length of time. International students were the main population of focus in almost half of the studies (Table 3). Similarly, they were also the main focus in seven discussion papers and eight of the literature reviews. Thirteen studies, three discussion papers and one review focused specifically on migrants. The remaining literature examined a mix of international students and migrants or were non-specific in their description of the student population (i.e., described as foreign-born or ESL students).

For migrant students, migration history or status were not reported in the description of the participants in any of the research papers nor were they mentioned or discussed in the review and discussion papers. There were five studies however, that implied based on other sections of the paper that they may have included student participants with a refugee or difficult migration background (i.e., political unrest in their country) [57, 77, 84, 104]. Only one research paper explicitly mentioned students with a refugee background in the introduction and discussion sections [57].

In the research studies with student participants (n = 73), students were mainly from East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia; top source countries in descending order, were China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Korea, India and Taiwan. Asian students (Taiwan = 1, India = 1, China = 1, and one unspecified) were also the population of interest in two discussion papers and two reviews. Instructors/educators were participants in 34% of studies (Table 3) and their perspectives were also explicitly mentioned in two of the literature reviews.

General overview of challenges, coping responses and supportive interventions

Language and communication barriers, including oral and written expression and comprehension, were the challenges highlighted most often in the literature [9, 17–20, 33, 34, 37, 42, 50–53, 55, 57–65, 67–76, 78–113, 115, 117–123, 125–131, 133, 134, 136, 139, 141–143, 145–148, 150–154]. Language and communication issues occur in academic and clinical settings as well as in social contexts. Learning nursing and medical terminology and colloquial expressions and adapting to a ‘low context communication’ style, were noted as particularly difficult. At the graduate level, academic writing was the major issue, including demonstrating critical analysis [71, 79, 80, 115, 130, 146, 148].