Abstract

An experimental model that demonstrates a mycoplasma species acting to potentiate a viral pneumonia was developed. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, which produces a chronic, lymphohistiocytic bronchopneumonia in pigs, was found to potentiate the severity and the duration of a virus-induced pneumonia in pigs. Pigs were inoculated with M. hyopneumoniae 21 days prior to, simultaneously with, or 10 days after inoculation with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), which induces an acute interstitial pneumonia in pigs. PRRSV-induced clinical respiratory disease and macroscopic and microscopic pneumonic lesions were more severe and persistent in M. hyopneumoniae-infected pigs. At 28 or 38 days after PRRSV inoculation, M. hyopneumoniae-infected pigs still exhibited lesions typical of PRRSV-induced pneumonia, whereas the lungs of pigs which had received only PRRSV were essentially normal. On the basis of macroscopic lung lesions, it appears that PRRSV infection did not influence the severity of M. hyopneumoniae infection, although microscopic lesions typical of M. hyopneumoniae were more severe in PRRSV-infected pigs. These results indicate that M. hyopneumoniae infection potentiates PRRSV-induced disease and lesions. Most importantly, M. hyopneumoniae-infected pigs with minimal to nondetectable mycoplasmal pneumonia lesions manifested significantly increased PRRSV-induced pneumonia lesions compared to pigs infected with PRRSV only. This discovery is important with respect to the control of respiratory disease in pigs and has implications in elucidating the potential contribution of mycoplasmas in the pathogenesis of viral infections of other species, including humans.

Traditionally it has been presumed that viral infections potentiate and increase the susceptibility of a host to bacterial infections. However, recent evidence indicates that members of the class of Mollicutes, which includes the mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas, may play a more significant primary role in viral diseases than was previously realized. In 1989, it was reported that a high proportion of AIDS patients were infected with Mycoplasma fermentans and Mycoplasma penetrans (4, 16). Since then, several other mycoplasmas, including Mycoplasma genitalium and Mycoplasma pirum, have been implicated in playing a synergistic role with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (2, 4). Evidence that supports the role that mycoplasmas play in accelerating the progression of HIV to AIDS has included the enhanced cytopathic effects (CPE) on tracheal epithelial cells (25) and human CD4+ lymphocytes (2) infected with both HIV and M. fermentans in vitro. The possible mechanisms by which mycoplasmas could influence the pathogenesis of HIV have not yet been elucidated, although mycoplasmas have been shown to activate B and T cells polyclonally both in vitro and in vivo (20, 24).

Recently, a new respiratory syndrome in swine, designated porcine respiratory disease complex (PRDC), has emerged as a serious health problem in most pig-raising regions of the world. Pneumonia in pigs with PRDC is due to a combination of both viral and bacterial agents. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), an Arterivirus (5), are two of the most common pathogens isolated from pigs exhibiting PRDC.

M. hyopneumoniae is recognized as the causative agent of porcine enzootic pneumonia, a mild, chronic pneumonia commonly complicated by opportunistic infections with other bacteria (22). The primary clinical sign associated with M. hyopneumoniae infection is a sporadic, dry, nonproductive cough. Other clinical signs, such as fever or impaired growth, are linked to secondary invaders, especially Pasteurella multocida. Typical mycoplasmal pneumonia lesions consist of well-demarcated dark-red-to-purple (acute) or tan-grey (chronic) areas of cranioventral consolidation. Microscopic examination reveals bronchopneumonia with suppurative and histiocytic alveolitis with peribronchiolar and perivascular lymphohistiocytic cuffing and nodule formation, typical of hyperplasia of bronchoalveolar lymphoid tissue.

In contrast, PRRSV induces a severe, acute pneumonia with clinical disease characterized by labored and accentuated abdominal respiration and tachypnea. Coughing is rarely observed. In addition, pigs infected with PRRSV exhibit elevated rectal temperatures, with pronounced lethargy and anorexia. Gross lesions associated with PRRSV infection consist of severe, multifocal to diffuse, tan-mottled consolidation of the lung. Microscopic lesions include septal infiltration with mononuclear cells, type II pneumocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and an alveolar exudate consisting of mixed inflammatory cells and necrotic macrophages.

The mechanisms by which PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae cause disease are quite different. PRRSV infects cells of the macrophage/monocyte/dendritic lineage. Pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PAMs) and pulmonary intravascular macrophages (PIMs) are the primary sites of replication in the lung (12, 28). Infection of PAMs and PIMs by PRRSV induces cell lysis, presumably resulting in a decreased ability of the respiratory tract to defend against both respiratory and systemic pathogens (9). In contrast, M. hyopneumoniae attaches to the cilia of tracheal epithelial cells, resulting in damage to epithelial cells and the mucociliary apparatus (6). The mechanisms explaining the lymphocytic infiltration observed with M. hyopneumoniae are unknown. The resulting lesions lead to consolidation of lung parenchyma and local invasion of opportunistic bacteria or viruses that can ultimately lead to systemic disease.

Consistent with other virus-bacterium interaction models, the most commonly proposed hypothesis is that PRRSV is the primary pathogen and bacteria are secondarily involved in the pathogenesis of PRDC. In the study reported here, we found that infection with M. hyopneumoniae potentiated and prolonged PRRSV-induced pneumonia clinically, macroscopically and microscopically. This report describes an in vivo model that conclusively demonstrates a potentiating effect on a viral infection by a mycoplasma species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pigs.

One hundred forty PRRSV- and mycoplasma-free crossbred (Landrace, large white, and duroc) pigs were obtained from a commercial herd at the ages of 10 to 14 days and were randomly assigned to seven treatment groups. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Iowa State University Institutional Committee on Animal Care and Use.

Inocula and experimental design.

The experimental design is summarized in Table 1. The pigs were 6 weeks old at day 0 (the day on which three of the four PRRSV groups were inoculated with PRRSV). An inoculating dose of 105 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of the high-virulence PRRSV strain ATCC VR-2385, passage 6, in a 5-ml volume was administered intranasally to pigs in groups A, B, C, and F (12). A tissue homogenate containing a derivative of M. hyopneumoniae 11 (105 color-changing units [CCU] per ml) was administered intratracheally to pigs in groups A, C, and E at a dilution of 1:100 in 10 ml of mycoplasmal Friis medium (23). M. hyopneumoniae was administered at a dilution of 1:50 in 5 ml of medium to pigs in groups B and D due to the younger age (3 weeks) and smaller size of the pigs at the time of inoculation.

TABLE 1.

Experimental design—infection status, sequence of inoculation, and number of pigs necropsied on each of three days

| Group | Infection status (day of inoculationa) | No. of pigs necropsied at:

|

Total no. of pigs necropsied | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 | Day 10 | Day 28 | |||

| A | PRRSV (0), M. hyopneumoniae (0) | 6 | 6 | 8 | 20 |

| B | PRRSV (0), M. hyopneumoniae (−21) | 6 | 6 | 8 | 20 |

| C | PRRSV (−10), M. hyopneumoniae (0) | 6 | 6 | 8 | 20 |

| D | M. hyopneumoniae (−21) | 6 | 6 | 8 | 20 |

| E | M. hyopneumoniae (0) | 6 | 6 | 8 | 20 |

| F | PRRSV (0) | 6 | 6 | 8 | 20 |

| G | Control (0) | 6 | 6 | 8 | 20 |

Pigs were 6 weeks old at day 0.

Serology.

Blood was collected periodically throughout the trial in order to evaluate antibody production. All sera were tested for antibodies against PRRSV with a commercially available enzyme-linked immunofluorescent assay (ELISA) (HerdChek: PRRS; IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Westbrook, Maine) according to the procedures described by the manufacturer. Samples were considered positive if the calculated sample-to-positive (S/P) ratio was 0.4 or greater. M. hyopneumoniae antibody titers were determined by ELISA as previously described (3). Known positive and negative sera were included as controls in each plate. Readings more than 2 standard deviations above the mean value of the negative control were considered positive.

PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae isolation and titration.

PRRSV isolation was performed by using bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid obtained at necropsy by lavaging the bronchi with 50 ml of minimal essential medium (MEM) containing antibiotics (9 μg of gentamicin/ml, 100 U of penicillin G/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml) (18). Virus isolation was then performed according to an established protocol (17). Virus titration was performed on 10% (wt/vol) homogenized lung tissues in MEM as previously described with several modifications (8). Briefly, 200 μl of 10-fold serial dilutions of lung homogenate was inoculated onto a confluent monolayer of CRL11171 cells for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The cultures were monitored daily for CPE. If CPE was not observed within 7 days, the cultures were frozen and thawed and blindly passaged three times to be considered negative. Monolayers were stained with an anti-PRRSV monoclonal antibody, SDOW-17 (South Dakota State University, Brookings), followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin and were viewed with a fluorescence microscope for evidence of specific viral antigens (14). M. hyopneumoniae was isolated from lung sections and titrated as previously described (22). Mycoplasma-appearing colonies that developed were specifically identified by using epiimmunofluorescence with conjugates prepared from rabbit antisera to M. hyopneumoniae 11 (7).

Clinical evaluation.

Pigs were evaluated daily for at least 15 min for clinical signs, including appetite, cough, increased respiration rate, or behavioral changes. A daily clinical respiratory score was assessed on days 0 to 14 according to a previously described system (14).

Pathologic examination.

Pigs were necropsied at either day 3, day 10, or day 28, as outlined in Table 1. The right rib cage was reflected, and the lungs were removed and evaluated for macroscopic lesions. A portion of lung was aseptically collected for M. hyopneumoniae and PRRSV isolation, fluorescent antibody assay (FA), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and histopathologic examination. The lungs were then lavaged, and BAL fluid was obtained. Lesions consistent with mycoplasmal pneumonia (dark-red-to-purple consolidated areas) were sketched on a standard lung diagram. The proportion of lung surface with lesions was determined from the diagram by using a Zeiss SEM-IPS image analyzing system (23). In contrast to mycoplasma-induced lesions, PRRSV-infected lungs were characterized by parenchyma that was mottled tan and rubbery and failed to collapse. The lung lesions were scored by using a previously developed system based on the approximate volume that each lobe contributes to the entire lung: the right cranial lobe, right middle lobe, cranial part of the left cranial lobe, and caudal part of the left cranial lobe each contribute 10% each of the total lung volume, the accessory lobe contributes 5%, and the right and left caudal lobes each contribute 27.5% (13). These scores were then used to calculate the total lung lesion score based on the relative contribution of each lobe.

Sections were taken from all lung lobes, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and routinely processed and embedded in paraffin in an automated tissue processor. Lung sections were blindly examined and given a score (0 to 4) for peribronchiolar and perivascular lymphoid cuffing and nodule formation consistent with M. hyopneumoniae-induced pneumonia lesions. The severity of PRRSV-induced and interstitial pneumonia lesions was also scored (0 to 6). The scoring systems are summarized in Table 4, footnotes a and b.

TABLE 4.

Microscopic lesion scores from pigs inoculated with either PRRSV, M. hyopneumoniae, or both

| Group | Score for pneumonia induced by PRRSVa or M. hyopneumoniaeb at the following necropsy date:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3

|

Day 10

|

Day 28

|

||||

| PRRSV | M. hyopneumoniae | PRRSV | M. hyopneumoniae | PRRSV | M. hyopneumoniae | |

| A | 1.2 ± 1.1 Bc | 0 | 4.0 ± 0.9 A | 1.7 ± 1.0 A | 4.8 ± 0.7 A | 3.9 ± 0.4 A |

| B | 1.0 ± 0 B | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 1.5 A | 0.8 ± 0.4 B | 1.3 ± 0.5 B | 1.6 ± 1.1 C |

| Cd | 3.3 ± 0.5 A | 0 | 3.3 ± 0.5 A | 1.8 ± 1.0 A | 4.3 ± 1.2 A | 3.8 ± 0.5 A |

| D | 0 C | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0 B | 0.5 ± 0.6 B,C | 0.1 ± 0.4 C | 1.0 ± 0 C |

| E | 0.2 ± 0.4 C | 0 | 0 B | 0.5 ± 0.6 B,C | 0 C | 2.5 ± 0.8 B |

| F | 1.5 ± 0.8 B | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.8 A | 0 C | 1.4 ± 0.5 B | 1.1 ± 0.6 C |

| G | 0.2 ± 0.4 C | 0 | 0 B | 0.8 ± 0.4 B,C | 0 C | 0.3 ± 0.5 D |

PRRSV scores are based on the severity of interstitial pneumonia. 0, no microscopic lesions; 1, mild multifocal pneumonia; 2, mild diffuse pneumonia; 3, moderate multifocal pneumonia; 4, moderate diffuse pneumonia; 5, severe multifocal pneumonia; 6, severe diffuse pneumonia.

M. hyopneumoniae scores are based on the severity of peribronchiolar and perivascular cuffing and lymphoid nodule formation, as follows: 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe; 4, very severe. 0, no microscopic lesions.

Within each column, values followed by different letters (A, B, C, or D) are significantly different from each other (P < 0.001).

Group C received PRRSV on day −10 and M. hyopneumoniae on day 0 and so is not matched with the other groups with respect to the number of days after inoculation with PRRSV.

PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae antigen detection.

PRRSV-specific antigen was detected in lung tissues by a previously described IHC method (10). IHC was performed on sections cut from one paraffin-embedded lung tissue block which included three pieces (1 by 2 cm) of lung, one each from the left cranial, accessory, and caudal lobes. The number of PRRSV antigen-positive cells was counted as described elsewhere. A direct immunofluorescence procedure was used for detection of M. hyopneumoniae as described previously (1).

Statistics.

Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). If the P value from the ANOVA was less than or equal to 0.05, pairwise comparisons of the different treatment groups were performed by least significant difference at the P < 0.05 rejection level.

RESULTS

Clinical disease.

Clinical respiratory disease data are presented in Table 2. All groups inoculated with PRRSV displayed signs of respiratory disease consistent with PRRSV-induced pneumonia by day 3 postinoculation. Signs included labored breathing and increased respiratory rate. Coughing was observed in all M. hyopneumoniae-inoculated groups beginning at days 10 to 14 but not in pigs infected with PRRSV only (group F).

TABLE 2.

Summary of average clinical respiratory disease scores of pigs by group after inoculation with PRRSV, M. hyopneumoniae, or both

| Group | Scorea at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1–3b (n = 20) | Day 4–10 (n = 14) | Day 11–14 (n = 8) | |

| A | 0.8 ± 0.4 B | 2.4 ± 0.7 A | 4.1 ± 0.5 A |

| B | 1.6 ± 0.4 A | 2.4 ± 0.5 A | 3.7 ± 0.6 A |

| C | 2.2 ± 0.8 A | 2.6 ± 0.5 A | 2.9 ± 0.6 B |

| D | 0 D | 0 C | 0 C |

| E | 0 D | 0 C | 0 C |

| F | 0.6 ± 0.3 C | 1.9 ± 0.4 B | 2.1 ± 1.4 B |

| G | 0 D | 0 C | 0 C |

Scores: 0, normal; 1, mild dyspnea and/or tachypnea when stressed; 2, mild dyspnea and/or tachypnea when at rest; 3, moderate dyspnea and/or tachypnea when stressed; 4, moderate dyspnea and/or tachypnea when at rest; 5, severe dyspnea and/or tachypnea when stressed; 6, severe dyspnea and/or tachypnea when at rest. Within each column, values followed by different letters (A, B, C, or D) are significantly different from each other (P < 0.001).

Pigs were 6 weeks old at day 0.

Analysis of the respiratory disease scores indicated that pigs infected with both M. hyopneumoniae and PRRSV had more severe clinical respiratory disease than the single-organism-infected groups. Group B, which was inoculated with M. hyopneumoniae 21 days prior to PRRSV inoculation, developed more severe respiratory disease within the first 3 days after PRRSV inoculation than any other PRRSV-infected groups. Overall, the pigs in groups A and B, which had received both PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae, had significantly more severe clinical respiratory disease than pigs inoculated with PRRSV alone (group F) or M. hyopneumoniae alone (groups D and E).

Respiratory scores from pigs in group C do not match those of the other PRRSV-infected groups due to the 10-day interval between the inoculation of group C pigs with PRRSV and the first determination of clinical scores shown in Table 2. Prior to inoculation with M. hyopneumoniae on day 0, the clinical scores of group C matched those of group F for the first 10 days following PRRSV infection, which for group C would be days −10 to 0 (data not shown). The respiratory scores for group C in Table 2 were determined 10 additional days post-PRRSV challenge. Thus, the score of 2.2 ± 0.8 for group C on days 1 to 3 in Table 2 was actually determined 11 to 13 days post-PRRSV challenge and could be compared to the scores in the final column, determined on days 11 to 14, for the other PRRSV-challenged groups. If the group C data on days 1 to 3 are compared to the data for the other PRRSV-challenged groups on days 11 to 14, the clinical disease in group C is equivalent to that in group F. However, even though there is no comparable PRRSV-only control that matches group C for more than 14 days postinoculation, the clinical respiratory disease in group C shows no evidence of regressing over the course of the monitoring period, extending to 24 days after inoculation with PRRSV.

Macroscopic lesions.

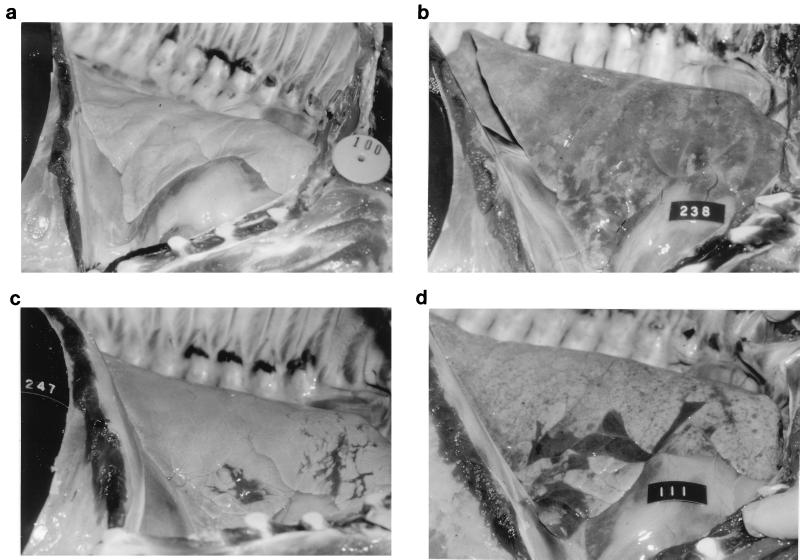

The mean percentages of lung tissue with visible pneumonia, either PRRSV-induced or M. hyopneumoniae-induced pneumonia, are summarized in Table 3. At necropsy on day 3, PRRSV-infected pigs were already exhibiting PRRSV-induced pneumonia. PRRSV-induced lesions consisted of lungs which were mottled tan or diffusely tan, were firmer and heavier than normal lungs, and failed to collapse upon removal from the chest cavity (Fig. 1b), compared to a normal lung (Fig. 1a). The pneumonia was well developed in group C, which had been infected with PRRSV 13 days prior to necropsy. No visible M. hyopneumoniae-induced pneumonia was observed at day 3.

TABLE 3.

Percentage of lung with visible pneumonia lesions in pigs infected with either M. hyopneumoniae, PRRSV, or both

| Group | % of lung exhibiting pneumonia induced by PRRSVa or M. hyopneumoniaeb at the following necropsy date:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3

|

Day 10

|

Day 28

|

||||

| PRRSV | M. hyopneumoniae | PRRSV | M. hyopneumoniae | PRRSV | M. hyopneumoniae | |

| A | 8.2 ± 4.5 Bc | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 50.8 ± 15.9 A | 4.1 ± 4.1 A | 42.9 ± 7.5 A | 7.7 ± 5.7 A |

| B | 12.3 ± 6.0 B | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 48.8 ± 26.4 A | 1.3 ± 2.2 B | 15.6 ± 14.5 C | 3.3 ± 5.9 B,C |

| Cd | 42.8 ± 12.8 A | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 29.5 ± 9.1 B | 2.5 ± 3.1 A,B | 28.8 ± 14.1 B | 7.2 ± 8.1 A,B |

| D | 0 C | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0 C | 0.9 ± 2.1 B | 0 D | 1.2 ± 3.0 C,D |

| E | 0 C | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0 C | 0.2 ± 0.2 B | 0 D | 8.3 ± 4.0 A |

| F | 13.7 ± 5.8 B | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 56.5 ± 12.7 A | 0.05 ± 0.1 B | 0.8 ± 1.59 D | 0 D |

| G | 0 C | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0 C | 0.02 ± 0.05 B | 0 D | 0 D |

As estimated by visual observation.

As determined by lesion sketches and image analysis.

Within each column, values followed by different letters (A, B, C, or D) are significantly different from each other (P < 0.001).

Group C received PRRSV on day −10 and M. hyopneumoniae on day 0 and so is not matched with the other groups with respect to the number of days after inoculation with PRRSV.

FIG. 1.

(a) Normal lungs from an uninfected pig. (b) Lungs from a pig infected 10 days previously with PRRSV. The lungs fail to collapse and are diffusely mottled and tan in appearance. (c) Lungs from a pig infected 28 days previously with M. hyopneumoniae. Lungs have multiple well-demarcated, dark-red areas of pneumonia in the cranioventral region. (d) Lungs from a pig dually infected 28 days previously with PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae, exhibiting both the characteristic failure to collapse and mottled tan appearance of PRRSV and the well-demarcated, dark-red consolidated areas typical of M. hyopneumoniae.

At day 10, the level of PRRSV-induced pneumonia were similar in groups A, B, and F, all of which had received PRRSV on day 0. The percentage of pneumonic lung lesions was lower in group C at day 10. However, pigs in group C, inoculated with PRRSV 10 days prior to receiving M. hyopneumoniae on day 0, were 20 days post-PRRSV challenge. Interestingly, groups A and C had higher percentages of pneumonic lung lesions due to M. hyopneumoniae than the M. hyopneumoniae-only group (group E). In addition, the mean percentages of lung tissue with mycoplasmal pneumonia in groups A and C were greater than those in either group B or group D, which had been inoculated with M. hyopneumoniae 31 days prior to necropsy. M. hyopneumoniae-induced lesions were easily differentiated from the PRRSV-induced lesions, as they consisted of well-demarcated areas of dark-red to purple firm parenchyma, located primarily at the ventral and cranial tips of the anterior and middle lobes (Fig. 1c).

At day 28, PRRSV-induced pneumonia was observed in only two of the eight pigs in the group inoculated with PRRSV only (group F). In contrast, PRRSV-induced lung lesions were observed in all pigs in the dually infected groups (groups A, B, and C) (Fig. 1d). The percentage of lung tissue with PRRSV-induced pneumonia lesions in group A was significantly greater than that in group B or C. The levels of mycoplasmal pneumonia were similar in groups A, C, and E, while groups B and D had minimal mycoplasmal lesions.

Microscopic data.

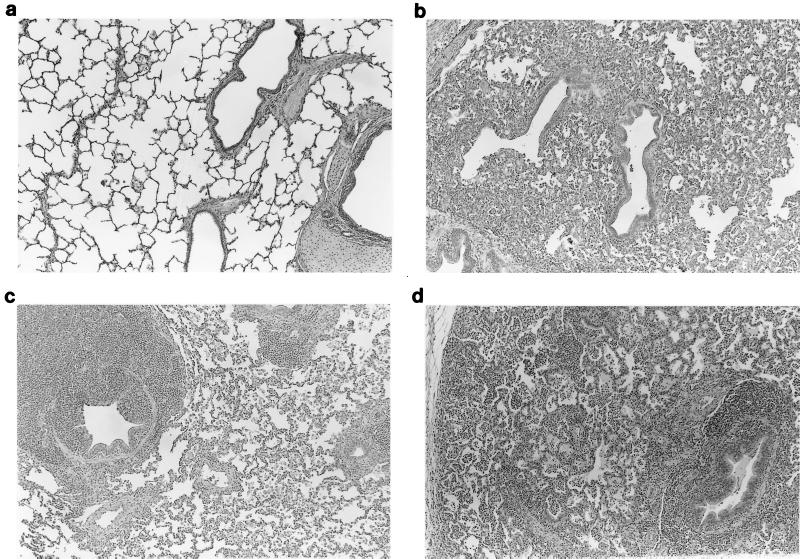

Histopathological evaluations are presented in Table 4. Interstitial pneumonia consistent with PRRSV-induced pneumonia was present in all PRRSV-infected pigs at day 3. This pneumonia was characterized by type 2 pneumocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia, septal infiltration with monocytes, and increased alveolar exudate consisting of macrophages, necrotic macrophages, multinucleated cells, and proteinaceous fluid. Groups A and B had microscopic lesions equivalent to those observed in pigs from group F (PRRSV only), whereas group C had more severe PRRSV-induced lesions, as expected due to its longer interval following PRRSV inoculation (13 days). M. hyopneumoniae-induced lung lesions were not yet observed at day 3.

Microscopic lesions consistent with PRRSV-induced interstitial pneumonia were similar in all PRRSV-infected pigs on day 10 (Fig. 2b). Peribronchiolar and perivascular lymphohistiocytic cuffing consistent with M. hyopneumoniae-induced pneumonia was observed and was significantly more severe in groups A and C than in group E at day 10 (Fig. 2c).

FIG. 2.

(a) Microscopic section of a normal lung from a pig. (b) Microscopic section of a lung from a pig infected 10 days previously with PRRSV. There is moderate diffuse interstitial pneumonia characterized by accumulation of necrotic debris and inflammatory cells in alveolar spaces, septal infiltration by mononuclear cells, and type 2 pneumocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia. (c) Microscopic section of a lung from a pig infected 28 days previously with M. hyopneumoniae. There is peribronchiolar and perivascular lymphoid hyperplasia characteristic of M. hyopneumoniae infection. (d) Microscopic section of a lung from a pig infected 28 days previously with PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae. Lesions characteristic of both M. hyopneumoniae- and PRRSV-induced pneumonia are present.

Groups A and C had significantly more severe PRRSV-induced interstitial pneumonia than group F (PRRSV only) at day 28. Microscopic lesions consistent with M. hyopneumoniae infection were also more severe in the dually infected groups A and C than in group E (M. hyopneumoniae only) at day 28 (Fig. 2d).

The mild peribronchiolar and perivascular lymphohistiocytic cuffing reported in the negative-control group and group F (PRRSV only) are nonspecific changes. There was no evidence of M. hyopneumoniae infection in either the negative-control group or group F based on culture, which is a more sensitive test for the presence of M. hyopneumoniae. Peribronchiolar lymphoid hyperplasia is considered the most characteristic lesion associated with M. hyopneumoniae infection; however, in cases of mycoplasmal pneumonia, it typically progresses to discrete peribronchiolar lymphoid nodule or follicle formation. However, these changes are not found only in pigs infected with mycoplasmas. Peribronchiolar lymphohistiocytic cuffing has been reported in pigs experimentally infected with PRRSV (13) or may simply be associated with chronic antigen stimulation from the environment. PRRSV-induced peribronchiolar lymphohistiocytic cuffing does not progress to discrete nodule formation and typically resolves by day 28 postinfection.

PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae isolation and titration.

PRRSV was isolated from BAL of all groups of PRRSV-infected pigs. PRRSV was isolated from the greatest number of pigs in groups A (12 of 20) and B (10 of 20), which had received M. hyopneumoniae either concurrently with or prior to inoculation with PRRSV, respectively (Table 5). Isolation of PRRSV from BAL peaked at day 10. Interestingly, at day 28, virus was isolated from only three of eight pigs in group A (concurrently infected with PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae) and one of eight pigs in group B (infected with M. hyopneumoniae prior to PRRSV), while all other pigs at that time were negative for PRRSV.

TABLE 5.

Isolation of PRRSV from BAL and titration of virus from lung tissue and number of cells with PRRSV antigen, as determined by IHC

| Group | PRRSV result at the following necropsy date:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3

|

Day 10

|

Day 28

|

|||||||

| BAL (no. pos.)a | IHC

|

BAL (no. pos.) | IHC

|

BAL (no. pos.) | IHC

|

||||

| No. pos.b | No. of cellsc | No. pos. | No. of cells | No. pos. | No. of cells | ||||

| A | 3/6 | 4/6 | 101.8 | 6/6 | 3/6 | 91.5 | 3/8 | 1/8 | 87.3 |

| B | 4/6 | 4/6 | 167 | 5/6 | 5/6 | 17.5 | 1/8 | 1/8 | 0.4 |

| Cd | 2/6 | 6/6 | 8.2 | 5/6 | 0/6 | 0 | 0/8 | 3/8 | 208.9 |

| D | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0 |

| E | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0 |

| F | 3/6 | 5/6 | 554 | 6/6 | 4/6 | 28.3 | 0/8 | 1/8 | 0.4 |

| G | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0 | 0/7 | 0/8 | 0 |

Number of pigs positive for PRRSV in BAL/total number of pigs in group. pos., positive.

Number of pigs with PRRSV antigen as detected by IHC/total number of pigs in group.

Average number of positive cells (mean number of positive cells in three lung sections) per pig with PRRSV antigen, as detected by IHC.

Group C received PRRSV on day −10 and M. hyopneumoniae on day 0 and so is not matched with the other groups with respect to the number of days after inoculation with PRRSV.

Titration of lung tissue for PRRSV revealed that the highest average titers of virus were found on day 10 in groups A, B, and F, with individual pig titers ranging from a TCID50 of 102 to 105.6. The highest percentages of pigs with virus isolated from the lung homogenate were found in groups A and B; in each of these two groups, 83% of infected pigs had detectable PRRSV in lung tissue at necropsy. No differences were observed in the levels of PRRSV between the various groups.

PRRSV antigen was detected in macrophages throughout the lungs of the PRRSV-infected pigs, as previously reported (12). The number of pigs which had PRRSV-positive cells was greatest at days 3 and 10 in groups A, B, and F (Table 5). By day 28, only one of eight pigs in each of these groups had PRRSV-positive macrophages. In group C, which had been inoculated with PRRSV 10 days prior to the other groups, six of six pigs were positive for PRRSV antigen by IHC at day 3, no positive cells were detectable at day 10, and three of eight pigs were positive by day 28. The six pigs in group C that were necropsied at day 10 were all negative; however, PRRSV-like lesions were moderate and multifocal (microscopic score, 3.3 of 6), and PRRSV was isolated from BAL of five of six pigs. It is not uncommon for animals with subacute PRRSV to have lesions consistent with PRRSV yet to have negative IHC. IHC is not as sensitive as virus isolation from BAL fluids. No statistical differences in the number of IHC-positive cells were observed between the dually infected groups, A, B, and C, and group F, infected with PRRSV only. However, there was a large variation in the number of positive cells among the individual pigs. In addition, no evidence of increased numbers of cells containing PRRSV antigen was observed in the areas of the lungs with microscopic lesions consistent with M. hyopneumoniae.

M. hyopneumoniae was isolated from all M. hyopneumoniae-inoculated groups. However, only 25% of pigs in group B (receiving M. hyopneumoniae on day −21 and PRRSV on day 0) and 10% of pigs in group D (receiving M. hyopneumoniae on day −21) were positive for M. hyopneumoniae by culture (Table 6). Groups A (receiving PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae concurrently) and C (receiving PRRSV on day −10) had the largest numbers of pigs positive for M. hyopneumoniae. However, no significant differences were observed in the mean titer of M. hyopneumoniae in lung tissue between the dually infected groups and the groups infected with M. hyopneumoniae alone (Table 6). All pigs in groups A, C, and E were positive for M. hyopneumoniae as determined by FA at day 28, while only three of eight and one of eight were positive in groups B and D, respectively.

TABLE 6.

Prevalence of M. hyopneumoniae as determined by lung culture, titration of lung tissue, and FA

| Group |

M. hyopneumoniae result at the following necropsy date:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3

|

Day 10

|

Day 28

|

|||||||

| No. of pigs positivea | Titerb | No. of pigs FA positive | No. of pigs positive | Titer | No. of pigs FA positive | No. of pigs positive | Titer | No. of pigs FA positive | |

| A | 5/6 | 105.0 | 0/6 | 5/6 | 106.0 | 4/6 | 8/8 | 106.6 | 8/8 |

| B | 1/6 | NDc | 0/6 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | 3/8 | ND | 3/8 |

| Cd | 3/6 | 106.0 | 1/6 | 5/6 | 107.2 | 6/6 | 8/8 | 107.0 | 8/8 |

| D | 1/6 | ND | 0/6 | 1/6 | ND | 1/6 | 3/8 | ND | 1/8 |

| E | 3/6 | 103.3 | 0/6 | 4/6 | 107.0 | 4/6 | 8/8 | 107.3 | 8/8 |

| F | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | 0/8 | ND | 0/8 |

| G | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | 0/7 | ND | 0/7 |

Number of pigs positive for M. hyopneumoniae in ground lung tissue.

CCU of M. hyopneumoniae per milliliter.

ND, not done.

Group C received PRRSV on day −10 and M. hyopneumoniae on day 0 and so is not matched with the other groups with respect to number of days after inoculation with PRRSV.

Serology.

All pigs challenged with PRRSV developed antibodies to PRRSV by day 10 as determined by ELISA (data not shown). None of the pigs developed antibodies to M. hyopneumoniae during the study, as expected from previous studies (23).

DISCUSSION

We have developed an experimental model demonstrating that a mycoplasma can act as a cofactor in potentiating a viral pneumonia. Differentiating between the disease induced by the two pathogens was simplified by the pronounced differences between their clinical manifestations and the resulting macroscopic and microscopic lesions. PRRSV infection is characterized by a severe, acute, diffuse, interstitial pneumonia, whereas M. hyopneumoniae induces a chronic, mild, localized bronchopneumonia. These differences in pathologic lesions enabled us to identify the increased severity and duration of the PRRSV-induced pneumonia observed in all pigs infected with both PRRSV and M. hyopneumoniae. M. hyopneumoniae potentiated the viral pneumonia independent of the time of viral infection. Surprisingly, even when M. hyopneumoniae did not uniformly induce observable lesions typical of mycoplasmal pneumonia, as observed in group B, the viral pneumonia was potentiated. This finding indicates that it is not just an additive effect of the different pathogens, but rather a potentiation of PRRSV-induced pneumonia by M. hyopneumoniae. Specifically, pigs in group B, which had received M. hyopneumoniae 21 days prior to PRRSV inoculation, had a low level of mycoplasmal pneumonia yet had PRRSV-induced lesions that persisted for 4 weeks after PRRSV inoculation. PRRSV-induced lesions typically are resolved by 4 weeks postinoculation, as confirmed by the group infected with PRRSV only (group F) (12).

PRRSV infection did appear to increase the severity of the macroscopic and microscopic M. hyopneumoniae-induced pneumonia at day 10 in groups A and C, which received PRRSV concurrently with or prior to inoculation with M. hyopneumoniae. However, in both groups of pigs, the percentages of lung tissue exhibiting macroscopic pneumonia consistent with M. hyopneumoniae were not increased at day 28, which is our usual end point for studies of mycoplasmal pneumonia. Microscopically, however, PRRSV and mycoplasmal lesions were more severe in groups A and C at day 28. These results were not observed in the pigs which were inoculated with M. hyopneumoniae prior to challenge with PRRSV (group B). These findings suggest that the presence of PRRSV early in infection with M. hyopneumoniae may increase the rate at which pigs develop mycoplasmal pneumonia and increase the damage induced at the cellular level but does not increase the overall percentage of lung tissue exhibiting macroscopic pneumonia.

Levels of either PRRSV or M. hyopneumoniae in tissue were not increased in dually infected pigs. This suggests that the increased severity and duration of PRRSV-induced pneumonia was not due to increased PRRSV or M. hyopneumoniae replication. These results support the hypothesis that the inflammatory response elicited in the course of mycoplasmal pneumonia may be a critical factor in the potentiation of PRRSV-induced disease and lesions. M. hyopneumoniae-induced pneumonia is characterized by the infiltration of the lung parenchyma by mononuclear cells consisting primarily of lymphocytes and macrophages (26). In addition, it has been demonstrated that M. hyopneumoniae has a mitogenic effect on swine lymphocytes (19). These findings suggest that activation of the immune system may contribute to the enhanced pneumonia observed in our model. M. hyopneumoniae’s attraction of these inflammatory cells may produce an ideal environment for PRRSV-induced inflammation to persist. These findings are consistent with PRRSV infection of cells of the monocyte/macrophage/dendritic cell lineage, which is one of the major cell types responding to M. hyopneumoniae infection. The steady influx of new monocytes/macrophages recruited by the relatively chronic M. hyopneumoniae infection may allow PRRSV to persist in the lungs at low levels for prolonged periods.

The specific cellular and subcellular mechanisms by which M. hyopneumoniae potentiates PRRSV are currently unknown. Recent studies conducted with humans have also identified mycoplasmas as potentially important cofactors in a number of chronic disorders, including AIDS, malignant transformation, chronic fatigue syndrome, and various arthritides (15, 21, 27, 29). These studies suggest that our findings are not unique or without precedent. The mechanisms by which mycoplasmas influence the pathogenesis of these diseases in humans have not been elucidated. However, mycoplasmas are likely candidates for initiating disease because they produce chronic, often mild infections and have potent immunomodulatory properties. Mycoplasmas could potentiate PRRSV by direct interaction with the virus, by interaction with cells from the immune system, or by inducing an inflammatory immune response by the secretion of cytokines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank F. C. Minion for editorial assistance. We also thank N. Upchurch, B. Erickson, T. Young, R. Royer, T. Boettcher, and T. Anderson for technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Pork Producers Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amanfu W, Weng C N, Ross R F, Barnes H J. Diagnosis of mycoplasmal pneumoniae of swine: sequential study by direct immunofluorescence. Am J Vet Res. 1984;45:1349–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baseman J B, Tully J G. Mycoplasmas: sophisticated, reemerging, and burdened by their notoriety. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:21–32. doi: 10.3201/eid0301.970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bereiter M, Young T F, Joo H S, Ross R F. Evaluation of the ELISA and comparison to the complement fixation test and radial immunodiffusion enzyme assay for detection of antibodies against Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in swine serum. Vet Microbiol. 1990;25:177–192. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanchard A, Montagnier L. AIDS-associated mycoplasmas. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:687–712. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins J E, Benfield D A, Christianson W T, Harris L, Hennings J C, Shaw D P, Goyal S M, McCullough S, Morrison R B, Joo H S, Gorcyca D, Chladek D. Isolation of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332) in North America and experimental reproduction of the disease in gnotobiotic pigs. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1992;4:117–126. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeBey M C, Jacobson C D, Ross R F. Histochemical and morphologic changes of porcine airway epithelial cells in response to infection with Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53:1705–1710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Giudice R A, Robillard N F, Carski T R. Immunofluorescence identification of mycoplasma on agar by use of incident illumination. J Bacteriol. 1967;93:1205–1209. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.4.1205-1209.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan X, Nauwynck H J, Pensaert M B. Virus quantification and identification of cellular targets in the lungs and lymphoid tissues of pigs at different time intervals after inoculation with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) Vet Microbiol. 1997;56:9–19. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(96)01347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galina L. Possible mechanisms of viral-bacterial interaction in swine. Swine Health Production. 1995;3:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halbur P G, Andrews J J, Huffman E L, Paul P S, Meng X J, Niyo Y. Development of a streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase procedure for the detection of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus antigen in porcine lung. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1994;6:254–257. doi: 10.1177/104063879400600219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halbur P G, Rothschild M F, Thacker B J, Meng X-J, Paul P S, Bruna J D. Differences in susceptibility of Duroc, Hampshire, and Meishan pigs to infection with a high virulence strain (VR2385) of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) J Anim Breed Genet. 1998;115:181–189. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halbur P G, Paul P S, Frey M L, Landgraf J, Eernisse K, Meng X-J, Andrews J J, Lum M A, Rathje J A. Comparison of the antigen distribution of two U.S. porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates with that of the Lelystad virus. Vet Pathol. 1996;33:159–170. doi: 10.1177/030098589603300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halbur P G, Paul P S, Frey M L, Landgraf J, Eernisse K, Meng X-J, Lum M A, Andrews J J, Rathje J A. Comparison of the pathogenicity of two U.S. porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates with that of the Lelystad virus. Vet Pathol. 1995;32:648–660. doi: 10.1177/030098589503200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halbur P G, Paul P S, Meng X-J, Lum M A, Andrews J J, Rathje J A. Comparative pathogenicity of nine U.S. porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) isolates in a five-week-old cesarean-derived colostrum-deprived pig model. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1996;8:11–20. doi: 10.1177/104063879600800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo S-C. Mycoplasmas and AIDS. In: Maniloff J, McElhaney R N, Finch L R, Baseman J B, editors. In Mycoplasmas: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 525–545. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo S C, Hayes M M, Wang R Y H, Pierce P F, Kotani H, Shih J W K. Newly discovered mycoplasma isolated from patients infected with HIV. Lancet. 1991;338:1415–1418. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92721-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng X-J, Paul P S, Halbur P G, Lum M A. Characterization of a high-virulence U.S. isolate of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in a continuous cell line, ATCC CRL 11171. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1996;8:374–381. doi: 10.1177/104063879600800317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mengeling W L, Lager K M, Vorwald A C. Diagnosis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1995;7:3–16. doi: 10.1177/104063879500700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messier S, Ross R F. Interactions of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae membranes with porcine lymphocytes. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:1497–1502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naot Y. In vitro studies on the mitogenic activity of mycoplasmal species toward lymphocytes. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4:S205–S209. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.supplement_1.s205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicolson G, Nicolson N L. Diagnosis and treatment of mycoplasmal infections in Gulf War illness-CFIDS patients. Int J Occup Med Immunol Toxicol. 1996;5:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross R F. Mycoplasmal diseases. In: Leman A D, Straw B, Glock R D, editors. Diseases of swine. 6th ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press; 1986. pp. 469–483. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross R F, Zimmermann-Erickson B J, Young T F. Characteristics of protective activity of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine. Am J Vet Res. 1984;45:1899–1905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simecka J W, Ross S E, Cassell G H, Davis J K. Interactions of mycoplasmas with B cells: antibody production and nonspecific effects. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:S176–S182. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_1.s176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stadtlander C T K-H, Watson H L, Simecka J W, Cassell G H. Cytopathogenicity of Mycoplasma fermentans (including strain incognitus) Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:289–301. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_1.s289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suter M, Kobisch M, Nicolet J. Stimulation of immunoglobulin-containing cells and isotype-specific antibody response in Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae infection in specific-pathogen-free pigs. Infect Immun. 1985;49:615–620. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.3.615-620.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor-Robinson D. Mycoplasmas in rheumatoid arthritis and other human arthritides. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:781–782. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.10.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thanawongnuwech R, Thacker E L, Halbur P G. Effect of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) (isolate ATCC VR-2385) infection on bactericidal activity of porcine intravascular macrophages (PIMs): in vitro comparisons with pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PAMs) Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;59:323–335. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai S, Wear D J, Shih J W-K, Lo S-C. Mycoplasmas and oncogenesis: persistent infection and multistage malignant transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10197–10201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]