Abstract

In this study, we aimed to investigate the taxonomy and various characteristics of Dunaliella salina IBSS-2 strain and describe its cultivation potential in mid-latitude climate during springtime. In addition, our analysis confirmed the essentiality of combining morphological, physiological, and other characteristics when identifying new species and strains of the genus Dunaliella, along with the molecular marker (internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of rDNA gene). The pilot cultivation of microalgae during the springtime in the south of Russia demonstrated that the climatic conditions of this region allow D. salina cultivation for biomass accumulation during this season, highlighting light and temperature conditions as the main factors determining the growth rate of D. salina. A two-fold increase in daily insolation and, consequently, in temperature in April resulted in a more than three-fold increase in productivity of D. salina culture. The maximum productivity of D. salina both in April and May was comparable and reached 2 g m−2 day−1, and the total yield for 8–10 days was about 14.5–16 g m−2. The additional CO2 supply into the D. salina culture did not show any significant effect on its growth rate; however, it contributed to maintaining the diversity of morphometric characteristics over a longer period of time. Changes in the morphological and morphometric characteristics of algal cells, including size reduction, were observed during the batch cultivation. Thus, the production potential of the green carotenogenic microalga D. salina was determined in the springtime, which allows expanding the seasonal interval of its cultivation in temperate latitudes.

Keywords: Dunaliella salina, Pilot-scale cultivation, Phylogeny, Productivity, Morphology

Introduction

Dunaliella salina is a well-known carotenogenic microalga used for producing natural beta‐carotene, biofeeds, biofuel, and nutritional supplements (Ben-Amotz et al. 1991; Borowitzka and Vonshak 2017; Khadim et al. 2018; Ben-Amotz 2019; da Silva et al. 2021). It is a high-value feed for animals used in aquaculture due to its nutritional value and biological activity (Supamattaya et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2020). Commercial cultivation of D. salina is mainly confined to the regions located in subtropical latitudes (Del Campo et al. 2007; Ben-Amotz et al. 2009; Borowitzka and Vonshak 2017; Wu et al. 2017; Díaz et al. 2021). Due to its climatic conditions, the southern part of Russian Federation enables D. salina cultivation in spring, summer, and autumn (Massyuk 1973; Chekushkin et al. 2019; Gudvilovich and Borovkov 2019), but growth rate and production value of microalgae depend significantly on seasonally changing weather conditions. The experience of year-round cultivation of D. salina in Spain (García-González et al. 2003) shows that its biomass productivity in the spring and summer seasons is comparable, with an average annual productivity about 1.65 g m−2 day−1. When D. salina is cultivated in outdoor photobioreactors, the main environmental factor determining a growth rate and carotenoids accumulation is solar irradiation level (Ben-Amotz 1987, 2019; Lamers et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2016; Borowitzka and Vonshak 2017). Photoperiod, in addition to light intensity, also has a strong influence on the biochemical composition and photosynthetic efficiency (Sui et al. 2019; Wolf et al. 2021). Large number of sunny days in the south of Russia in spring, along with a considerably lower level of solar insolation compared to July and August, combined with a comparable duration of the photoperiod, provide favorable conditions for microalgae growing (Massyuk 1973; Terez et al. 2012; Chekushkin et al. 2019; Chekushkin et al. 2020; NASA LaRC POWER Project 2021).

The average daytime temperature in the southwestern part of the Crimean Peninsula in spring is close to the optimal one for active growth of D. salina (Massyuk 1973; Borowitzka and Vonshak 2017; NASA LaRC POWER Project 2021), and a slight decrease in temperature during the night period may contribute to a reduction of night biomass loss (Edmundson and Huesemann 2015). However, returning cold snaps and a sudden decrease in culture medium temperature can be a limiting factor for growing microalgae in open ponds. One of the approaches for increasing and stabilizing the temperature as well as protecting microalgae against precipitation is to place ponds with microalgae culture inside greenhouse units. This method was previously tested for pilot cultivation of D. salina in the late autumn in the greenhouse unit at the premises of A.O. Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas of RAS (IBSS), Sevastopol, Russia (Chekushkin et al. 2019; Gudvilovich and Borovkov 2019).

The main morphological characteristic of D. salina is high variability (level of plasticity) of this species, due to which its cells easily change shape and size in response to changes in environmental conditions, and morphological, morphometric, and physiological parameters of D. salina cells may change significantly depending on its cultivation conditions (Oren 2005; Preetha et al. 2012; Borovkov et al. 2019). Therefore, species identification based only on morphological analysis may not be reliable and may lead to incorrect conclusions (Borowitzka and Siva 2007; Polle et al. 2020). Phylogenetic approaches are generally accepted in aiding the classification of Dunaliella species, with ribosomal markers being at the forefront of genotyping (Olmos et al. 2009; Assunção et al. 2012). Currently, most authors agree that due to very high species diversity of the genus Dunaliella, it is necessary to use a comprehensive research approach, including morphological, physiological and phylogenetic analysis of the species.

IBSS-2 strain has been in the IBSS collection for more than 15 years and has demonstrated a high productive potential for biotechnological purposes (Borovkov et al. 2020a). Previous research of D. salina IBSS-2 strain under pilot outdoor cultivation in summer (Borovkov et al. 2020b) has demonstrated its high biomass and carotenoids productivity, yielding up to 3 g of carotenoids from 1 m2 of initial Dunaliella culture during the technological cycle of 20–25 days. Nevertheless, no phylogenetic analysis of this strain has been performed earlier.

To determine productivity capacity of IBSS-2 D. salina strain in the southern regions of the Russian Federation in spring, we investigated growth and morphometric characteristics of D. salina culture during cultivation in the pilot algobiotechnological unit; in addition, taxonomic status verification of the studied strain was carried out for the first time.

Materials and methods

Microalgal strain and verification of its taxonomy

The unialgal culture of green halophilic alga D. salina (Teodoresco, 1905) was used in the present research (strain IBSS-2 from IBSS common use center “World Ocean hydrobionts collection,” Sevastopol, Russia).

DNA isolation, PCR amplification, sequencing, and phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using two DNA sequences: a fragment of the ribosomal 18S rRNA gene and an internal transcribed spacer ITS (ITS1, 5.8 S rRNA and ITS2) with an aim to clarify the taxonomy of the strain used in the experiment. The investigation was carried out at the premises of the Resource Center “Molecular Structure of Matter” of Sevastopol State University.

DNA was isolated using a DNA-Extran 2 kit (Syntol, Russia) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

A gene fragment of 18S rRNA was amplified using conserved primers MA1 and MA2 (Olmos et al. 2000, 2009). Reactions were carried out in T100 thermal cycler (Bio Rad, US) with a total volume of 25 µL containing a PCR mix (ScreenMix, Evrogen), 1 µL of each primer (10 µM), and 100 ng of genomic DNA.

The internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) (700 bp), including ITS1, 5.8 S rRNA, and ITS2, was amplified using ITS1 and ITS4 primers (Preetha et al. 2012).

Bidirectional DNA sequencing was performed using the same primers as for PCR. The similarity searches with available NCBI GenBank database were carried out using the BLASTN algorithm (Zhang et al. 2000; Morgulis et al. 2008). Multiple alignment with various available sequences was performed using the Muscle algorithm, and phylogenetic analysis was carried out in the MEGA X software (Kumar et al. 2018). Alignment filtering was performed using Gblocks software and manually in the Bioedit software. The best nucleotide substitution model for ITS region was determined using jModelTest 2.1.10 (Darriba et al. 2012). The maximum likelihood method (with 1000 bootstrap replications) was used to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree. C. reinhardtii and Y. unicocca UTEX243 were selected as outgroup.

Cultivation conditions

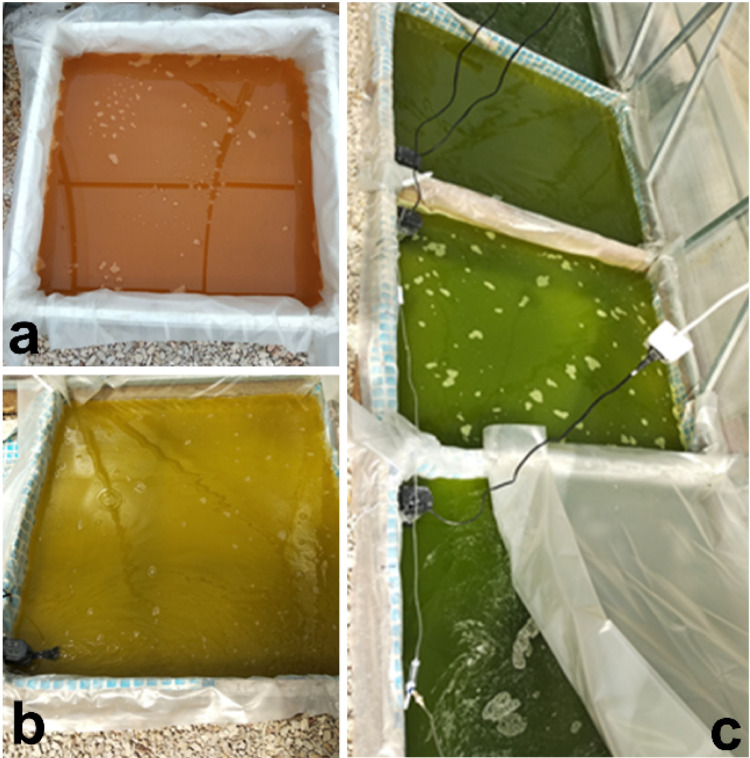

Outdoor pilot-scale cultivation of algae was carried out in an algobiotechnological greenhouse module made of polycarbonate at the premises of Department of Biotechnology and Phytoresources, IBSS, Sevastopol, Russia (44°36′54.6ʺN 33°30′11.7ʺE). Algae were grown in rectangular ponds (1 × 1 m), covered with polyethylene film and laid on the leveled ground, culture layer depth was 8 cm and culture volume in one experimental pond was 80 L (Fig. 1). Cell suspension was continuously stirred by aquarium pump Atman AT-201 (Chuangxing Electrical Appliances Co., Ltd, China). Microalgal culture was grown in the modified culture medium according to Shaish et al. (1990). Modification consisted in addition of sea salt (“Galit”, Russia) up to 120 g L−1 concentration.

Fig. 1.

General view of pilot-scale ponds in outdoor greenhouse unit. a D. salina culture which was used as an inoculum for the experiment in April. b Experiment in April. c Experiment in May

D. salina pilot cultivation was performed in batch mode in April and May, 2019. Culture of D. salina maintained in greenhouse during previous winter period (from December to March) was used as an inoculum for the experiment in April (Fig. 1a), so that it was preadapted to the outdoor light and illumination conditions. The inoculum was diluted with nutrient medium with the ratio of 1:9. The experiment conducted in May consisted of three variations: variant 1 involved shading of the pond with a polyethylene film, variant 2 featured additional supply of CO2 (2–3% v/v), while variant 3 served as control.

The dynamics of culture medium temperatures and insolation at the location of the pilot unit in April and May are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The dynamics of temperature (a) in D. salina culture in April (unfilled circle) and May: variant 1 (shading) (filled circle), variant 2 (additional CO2) (filled triangle), variant 3 (control) (filled diamond); and the dynamics of all sky insolation incident on a horizontal surface during the experiments in April (b) and May (c) (data were obtained from the NASA Langley Research Center (LaRC) POWER Project funded through the NASA Earth Science/Applied Science Program 2021)

Analytical methods

Biomass dry weight concentration was measured photometrically. Microalgal suspension optical density at 750 nm (D750) was measured by a Unico 2100 photometer (United Products & Instruments, USA) in 5 mm pathway cuvettes; absolute measurement error did not exceed 1.0%. 750 nm wavelength for measuring the optical density of the culture is selected so that changes in the pigment composition of algae have minimal effect on the data obtained, since major pigments (chlorophyll and carotenoids) do not contribute to the absorption spectrum at this wavelength (Griffiths et al. 2011). Optical density units (o.d.u.) (D750) conversion to biomass dry weight (DW) values was expressed as follows:

where DW is biomass dry weight; D750 is culture optical density; k is conversion factor. Empirical conversion factor (k = 0.78 g L−1 o.d.u.−1) was defined previously (Borovkov et al. 2020a).

The maximum productivity (Pm) was calculated by approximating growth curve at the linear growth phase part on the basis of biomass (B) and cell number (N):

where Bl is culture density at the beginning of linear growth phase; Nl is cell density at the beginning of linear growth phase; tl is the time at the beginning of linear growth phase (Lelekov and Trenkenshu 2007).

Cell density (N, cell mL−1) was measured with a hemocytometer (Gorjayev’s chamber, MiniMed, Russia) using a light microscope Carl Zeiss Axiostar Plus (Carl Zeiss company, Germany) (Absher 1973). Morphometrical characteristics of D. salina living culture samples were analyzed at microphotographs with the use of a light microscope Carl Zeiss Axiostar Plus (Carl Zeiss company, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a digital camera Canon PowerShot a620 (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and computer program Micam (Science4all 2009). Cell length (L) and width (D) were measured and cell volume (V) was calculated using prolate spheroid formula (Sun and Liu 2003):

where H is the third axis of ellipse and ellipsoid.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrographs of D. salina cells were obtained with a Hitachi SU3500 (Japan) scanning electron microscope at magnification of 6000×. Samples were prepared according to the protocol described by Pomroy (1989), which included the following steps: fixation with 2.5% glutaric aldehyde solution (“Merck”, Germany); sample concentration on the track membrane with 2 µm pore diameter (Dubna Cluster, Russia); critical point drying using Leica EM CPD300 (Germany); Au/Pd coating using Leica EM ACE200 (Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Libre Office and Scidavis software. Arithmetic mean (), standard deviation (SD), error of the mean, and confidence intervals for the mean (Δ) were estimated. All calculations were made for the significance value α = 0.05. Figures represent the means of three samples and their confidence intervals ( ± Δ).

Results

Phylogenetic analysis of IBSS-2 D. salina strain. Results of amplification and sequencing of molecular markers

Amplification of the ribosomal 18S rRNA gene with primers MA1 and MA2 from the IBSS-2 strain of D. salina in the present study yielded products of approximately 1800 bp.

Taxonomy of the IBSS-2 strain was verified by reconstructing phylogenetic relationships using the maximum likelihood (ML) method. The nucleotide sequences of ITS1, 5.8 S rRNA, and ITS2 were used for the analysis; the results are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Maximum likelihood tree of D. salina IBSS-2 strain. The nucleotide sequence of ITS rDNA (678 np) was used. Bootstrap values were retrieved from 1000 replicates and those > 75% are indicated at the nodes. The outgroup was C. reinhardtii and Y. unicocca UTEX243

The IBSS-2 strain studied in this research forms a clade with a group comprising several different Dunaliella species, which at the same time have identical ITS sequences. It is worth noting that the same clade contains D. salina CCAP 19/31 (Emami et al. 2015).

Production characteristics

Production characteristics of IBSS-2 D. salina strain were studied in the course of batch cultivation in outdoor greenhouse pilot unit in April and May.

When D. salina was grown in April, a lag-phase of culture growth was observed over the first four days. Some time was required to readjust metabolism of microalgae cells and to transition of the culture to the “green“ stage, because D. salina cells used as an inoculum corresponded morphologically to its “red” form (Fig. 1a, b). We could distinguish two linear growth sections on the batch growth curve of D. salina with different biomass and cell density productivity rates: from the 3rd day to the 12th day and from the 12th day to the 16th day (Fig. 4a, b). These linear growth areas corresponded to the time intervals with different temperature and solar irradiation conditions (Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 4.

The dynamics of biomass and cell density of D. salina in April (a, b) and May (c, d), respectively; variant 1 (shading) (filled circle), variant 2 (additional CO2) (filled triangle), variant 3 (control) (filled diamond). Dashed lines in (a) and (b) indicate linear growth phase approximation. Values are means ± confidence intervals, n = 3

Thus, biomass productivity in April (Pm) was 0.008 g L−1 day−1 (0.64 g m−2 day−1) from the 3rd day to the 12th day, and it was 3.3 times higher from the 12th day to the 16th day, making 0.026 g L−1 day−1 (2.08 g m−2 day−1). Productivity by cell number also increased during these time intervals, correlating with the change in biomass productivity of the culture, reaching 1.2 × 10–4 cell∙mL−1∙day−1 from the 2nd day to the 16th day and 4.6 × 10–4 cell∙mL−1∙day−1 from the 11th day to the 15th day. It is worth noting that daily-averaged insolation during the first period of linear growth was 2.9 kW h m−2 day−1, whereas it was two-fold higher at 11th–16th days of cultivation, making 5.8 kW h m−2 day−1 (Fig. 2b). Daytime temperature of algal suspension followed approximately the same trend (Fig. 2a).

When D. salina was grown in May, the pattern of changes in culture density and D. salina cell number also was similar in all experimental variants (Fig. 4c, d). Both biomass and cell number reached their maximum values on the 7th–8th day of cultivation, and decreased afterwards. The maximum cell density did not differ significantly in all three experimental variants and averaged about 3 × 106 cell mL−1. During the experiment in May biomass productivity was 0.022 g L−1 day−1 (1.76 g m−2 day−1) both in the control and in the shaded variant, while CO2 addition resulted in 0.025 g L−1 day−1 (2 g m−2 day−1) biomass productivity under daily-averaged insolation of 6.5 kW h m−2 day−1 (Figs. 2c, 4c). D. salina biomass yield obtained during 8 days of cultivation varied insignificantly for all variants of the experiment and amounted to 15–16 g m−2.

Morphometric and morphological characteristics

Morphometric characteristics of D. salina cells varied in the course of cultivation in April. Thus, the mean cell length and mean cell width decreased by 32% (from 19.25 ± 0.47 to 13.04 ± 0.27 µm) and 10% (from 10.43 ± 0.3 to 9.69 ± 0.2 µm), respectively, from the 1st to the 11th day of cultivation. The mean cell volume decreased by 42% over this period (from 1136.9 ± 83.1 to 655.1 ± 33.4 µm3).

The analysis of morphological appearance on SEM micrographs demonstrated that D. salina cells were unicellular and ellipsoidal with two flagella of the same length (Fig. 5). At the beginning of cultivation, the cells were large, more expanded in the apical part, with a wrinkled surface (Fig. 5a). In the course of cultivation, cell size decreased, and their shape became more elongated and drop-shaped with an almost smooth surface structure (Fig. 5b, c).

Fig. 5.

SEM micrographs (×6000) of D. salina cells during the experiment in April in the beginning of cultivation (a) and during the linear growth phase (b, c)

During the batch cultivation in May, morphometric characteristics of D. salina cells also changed significantly, and the pattern of their changes was similar for all three variants of the experiment. From the beginning to the 8th day of batch growth, mean cell length decreased by 20% (from 10.3 ± 0.5 to 8.5 ± 0.3 µm) and mean cell width decreased by 35% (from 6.7 ± 0.4 to 4.3 ± 0.2 µm). The mean cell volume of D. salina also decreased over this time period more than three times in all experimental variants (Fig. 6a). After the 9th day, stabilization of cell volume value was observed as the algal culture reached a stationary growth phase; and by the end of D. salina cultivation, its mean cell volume in all three variants of the experiment did not change significantly compared to the 8th day.

Fig. 6.

Mean cell volume dynamics during D. salina batch outdoor cultivation in May (a): variant 1 (shading) (filled circle), variant 2 (additional CO2) (filled triangle), variant 3 (control) (filled diamond); and the percentage of cells with different volume in D. salina culture during its batch outdoor cultivation in May: variant 1, shading (b); variant 2, additional CO2 (c); variant 3, control (d). Values are means ± confidence intervals, n = 3

The analysis of a size structure of D. salina culture in May revealed that large cells (more than 500 µm3) fraction was the highest in the beginning of cultivation in all experimental variants (comprising about 20%), while small cells (less than 50 µm3) were not observed in any of the experimental variants during this stage (Fig. 6b–d). The small cells fraction of D. salina culture significantly increased (up to 12%) in the course of its active growth stage (from the 1st to the 7th day). On the contrary, the large cells fraction decreased, and they were not observed in control and shaded variants after 6–7 days, while in the variant with additional CO2 injection they were still visualized up to 10 days of cultivation (Fig. 6b–d). Small cells of D. salina remained in culture also after the end of its active growth until the end of cultivation.

In addition, we noted morphological changes in D. salina cells in the course of its cultivation in May (Fig. 7). In the beginning of cultivation, D. salina cells had green coloration, tight cell wall, a chloroplast without inclusions, and a clearly visible pyrenoid. In the process of growth and aging of the culture, small inclusions in form of lipid globules were visualized in the cells starting from the 8th day (phase of growth declining and stationary phase). By the 8th day of cultivation, a granular chloroplast was prominent in cell structure; the cells acquired an orange tone. These changes were most pronounced in D. salina cells with an additional supply of CO2, which may give additional evidence of activation of carotenogenesis process (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Light micrographs of typical D. salina cells at the different times of its batch outdoor cultivation in May: variant 1, shading; variant 2, additional CO2; variant 3, control. Scale bar is 5 µm

Discussion

Phylogenetic analysis of IBSS-2 D. salina strain

Molecular characterization based on 18S rRNA gene size

As indicated in the results, the length of ribosomal 18S rRNA gene extracted from the IBSS-2 strain of D. salina was ~ 1800 bp. It was previously demonstrated (Olmos et al. 2009) that different known Dunaliella species have PCR products of different lengths, and their size allows differentiation between D. tertiolecta and D. salina, in particular. 18S rDNA of D. tertiolecta has no intron and forms a product of ~ 1770 bp, D. salina (~ 2170 bp) has only one intron at the 5′ end, D. viridis (~ 2495 bp) has one longer intron at the 5′ end, and D. parva and D. bardawil (~ 2570 bp) have two introns, one at either of the 5′ and 3′ ends. Importantly, the authors of a recent study (Highfield et al. 2021) isolated several D. salina strains with a PCR product length of ~ 1800 bp and concluded that intron size method used to distinguish D. tertiolecta from D. salina had limitations and must be supplemented by biochemical, physiological, and other analyses. Thus, this method of phylogenetic analysis of Dunaliella does not provide an unambiguous conclusion about taxonomic affiliation, and hence, an analysis based on other molecular markers was carried out.

Phylogenetic analysis based on ITS sequences

Four forms of D. salina were previously described in the literature, with a substantial difference in their cell shapes and sizes (Massyuk 1973; Highfield et al. 2021). This division may be ambiguous, since a shape of the cells can vary significantly depending on different environmental conditions. For this reason, morphological characteristics are not sufficient or reliable to identify the Dunaliella species, even taking into account physiological characteristics (such as different tolerance to high salinity and carotenogenic ability) (Avron and Ben-Amotz 1992). A number of molecular markers have been proposed for the identification of algae species: LSU rDNA, ITS, rbcL, and tufA (Olmos et al. 2009; Assunção et al. 2012; Preetha et al. 2012; Leliaert et al. 2014; Highfield et al. 2021), and it was concluded that internal transcribed spacer ITS was the most suitable. Therefore, ITS region (ITS1, 5.8 S rRNA, ITS2) was used for phylogenetic analysis in this study.

Previous studies on the phylogeny of the genus Dunaliella identified the following main clades of Dunaliella salina: salina-clade I, salina-clade II, Pseudosalina-clade (Assunção et al. 2012). The salina-clade III was additionally distinguished in (Highfield et al. 2021). The studied strain D. salina IBSS-2, together with D. salina CCAP 19/31, forms a clade with a group that also includes other Dunaliella species, but with identical ITS sequences (Fig. 3).

Polle et al. (2020) pointed out that the taxonomy of species within the genus Dunaliella is still adjustable, and the issue of distinguishing new species or even subspecies is still unresolved. Therefore, morphological, physiological, and other characteristics of the strains must be considered in addition to the molecular marker (internal ITS transcribed spacer of the rDNA gene) to identify the species of the genus Dunaliella.

The studied IBSS-2 strain was previously shown to tolerate high salinity (240 g L−1), accumulate carotenoids in concentrations up to 8% of ash-free dry weight (Borovkov et al. 2020a), and have morphological and morphometric characteristics corresponding to D. salina species. Thus, it is confirmed that the investigated IBSS-2 strain belongs to the species D. salina according to the combination of morphological, physiological, and molecular characteristics.

Production characteristics

There are two approaches for large-scale production of D. salina: either one-stage intensive cultivation or a two-stage mode, when the first stage is used for culture density accumulation and then a stress effect is applied for induction of carotenogenesis (Ben-Amotz 1995; García-González et al. 2003). As for the mass culture of D. salina in the south of Russia, a suitable strategy in the springtime is one-stage intensive batch growth or semi-continuous cultivation in order to increase its biomass, taking into account that the temperature and insolation levels are insufficient for culture transition to the «red» (carotenogenesis) phase.

According to our experimental results, the biomass yield of D. salina obtained in April and in May was quantitatively comparable. The change in weather conditions and an increase in both temperature and solar radiation in April resulted in a significant increase in the biomass productivity of D. salina (more than three-fold). The total yield for the 11 days of culture growth in April (excluding the days required for culture adaptation to the altered conditions) was 14.4 g m−2 for overall received solar energy of 55 kW h m−2. It should be noted that biomass yield over the last four days of cultivation amounted to more than 50% of the total yield due to an increase in both air temperature and insolation. The daily-averaged insolation during D. salina cultivation in May was 30% higher than in April, and the culture yield was 15–16 g m−2 for 8 days of growth with a total received insolation of 58 kW h m−2. Thus, the biomass yield of D. salina obtained in April and in May was similar and depended on the level of the total received insolation under experimental conditions, but the duration of its production in May was 1.4 times less. Nevertheless, the results indicate that D. salina productivity potential of 2 g m−2 day−1 can be achieved both in April and May under the optimum level of solar energy and temperature. According to the long-term observations, the total amount of photosynthetically active radiation at the latitude of cultivation site in May is higher by 5–20% than in April (Chekushkin et al. 2020; NASA LaRC POWER Project 2021). Our results on the culture productivity in the springtime in the south of Russia are similar to the corresponding data obtained from Spain in the spring using open ponds with the same culture depth layer (García-González et al. 2003). Carbon dioxide supply during D. salina cultivation provided maintenance of pH 8 in the algal culture, but foam formation occurred on the surface of cell suspension. This generally indicates an active culture growth process, but can also have a negative impact on efficient utilization of light energy. In the variant with shading, pH and daytime temperatures were lower than in the control one (by 0.1–0.2 units and 1–2 °C, respectively), which had no significant effect on the observed productivity. It is likely that there was no productivity reduction in the variants with shading and with the CO2 supply due to the decrease in stress light and temperature effects. The average productivity of D. salina during cultivation in May did not vary significantly in all variants of the experiment; however, a slight upward trend in growth rate was noted in the variant with CO2 supply.

Morphometric and morphological characteristics

D. salina cells in our experiments were 13–19 µm in length, about 10 µm in width in April, and 8–10.6 µm in length, 4–7 µm in width in May. Average cell volume ranged from 655 to 1137 μm3 in April and from 76.7 to 297.2 μm3 in May. According to the literature, the size of D. salina cells varies in a rather wide range, with cell length of 2.8–40 µm, cell width of 1.5–20 µm, and cell volume ranging from 8 to 4500 µm3 (Massyuk 1973; Oren 2005; Preetha et al. 2012). Therefore, the IBSS-2 strain has intermediate position in terms of its size characteristics. It is indicated in the literature that an increase in the length-to-width ratio of Dunaliella cells is a characteristic response to an increase in nutrients concentration (Massyuk 1973; Preetha et al. 2012). The increase in this ratio in D. salina cells (1.3–1.4 times) was most pronounced at the linear growth stage in May under a sufficient amount of nutrients in the medium and corresponded to an increase in cell number and culture density.

The size structure of D. salina culture changed significantly in the course of batch cultivation both in April and May. A culture of D. salina at the “red” stage with larger cells (with an average cell volume 1136.9 ± 83.1 µm3) was used as an inoculum in April; and a culture at the stationary growth phase of the “green” stage (mean cell volume 297.2 ± 45.2 μm3) was used in May. During the batch cultivation, the mean volume of D. salina cells decreased 1.7-fold in April and three-fold in May; this process in both cases was consistent with active growth of the culture. The transition of D. salina culture from the “red” to the “green” stage, as well as to an active growth stage, is usually accompanied by a significant decrease in its cell size (Massyuk 1973), as was observed in the experiments. Generally, the size of D. salina cells during its cultivation in April and in May differed significantly: in April, cells were on average 1.5–2 times larger (both in length and width) than in May. Apparently, such a considerable difference in the size of D. salina cells can be explained by the similar differences in the size characteristics of the cells of the inoculum culture in April and May.

Throughout the cultivation of D. salina in May, distribution of cells groups by volume varied, indicating a change in age structure of the cell population: the fraction of large cells in all variants of the experiment decreased (from 20 to 0%), and the fraction of small cells significantly increased (up to 10% or more); most of the cells in the culture were medium-sized (Fig. 7). Both large and small cells of D. salina were observed for a longer time in the variant with additional CO2 supply, and their ratio was slightly higher than in the other two variants of the experiment. The increased proportion of large D. salina cells at the initial stages of the experiment in May can be explained by the use of a culture that was in the stationary phase as an inoculum, since large “old” cells predominate at this growth stage. The maximum D. salina cell density was observed by the 7th–8th days of cultivation in May for all variants of the experiment, and then its growth almost ceased (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, the percentage of small cells in the variants without additional CO2 injection began to decrease.

Thus, according to the combination of changes in growth, morphological, and morphometric parameters, the optimal duration of cultivation of D. salina culture in May under the experimental conditions was about eight days.

Conclusions

Phylogenetic analysis confirmed the taxonomy of the studied strain and the requirement to take into account morphological and physiological characteristics, along with the molecular marker (ITS), when identifying Dunaliella species.

The climatic conditions of the south of Russia allowed successful cultivation of D. salina in the spring with productivity reaching 2 g m−2 day−1. Morphometric and morphological cell characteristics changed during batch cultivation corresponding to the physiological state. The total yield both in April and in May was similar (14.5–16 g m−2) due to comparable total insolation; thus, our investigation confirmed the possibility of extending a seasonal period of D. salina cultivation in this climatic zone. The results of this study can be used for further optimization of D. salina outdoor cultivation and maximization of carotenoids yield in different seasons.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by A.O. Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas of RAS, governmental research assignment # 121030300149-0 (AAAA-A18-118021350003-6) and an internal grant of Sevastopol State University for 2021 No. 30/06-31.

Author contributions

ABB conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision. ING methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft. ALA investigation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. AOL methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft. OAR methodology, investigation. OAM formal analysis, investigation. IVD investigation. AAC investigation.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

References

- Absher M (1973) Hemocytometer counting. In: Kruse PF Jr, Patterson MK Jr (eds) Tissue culture: methods and applications. Academic Press, New York, pp 395–397. 10.1016/B978-0-12-427150-0.50098-X

- Assunção P, Jaén-Molina R, Caujapé-Castells J, de la Jara A, Carmona L, Freijanes K, Mendoza H. Molecular taxonomy of Dunaliella (Chlorophyceae), with a special focus on D. salina: ITS2 sequences revisited with an extensive geographical sampling. Aquat Biosyst. 2012;8:2. doi: 10.1186/2046-9063-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avron M, Ben-Amotz A, editors. Dunaliella: physiology, biochemistry, and biotechnology. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Amotz A. Effect of irradiance and nutrient deficiency on the chemical composition of Dunaliella bardawil Ben-Amotz and Avron (Volvocales, Chlorophyta) J Plant Physiol. 1987;131(5):479–487. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(87)80290-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Amotz A. New mode of Dunaliella biotechnology: two-phase growth for β-carotene production. J Appl Phycol. 1995;7(1):65–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00003552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Amotz A. Bioactive compounds: glycerol production, carotenoid production, fatty acids production. In: Ben-Amotz A, Polle JEW, Subba Rao DW, editors. The Alga Dunaliella, biodiversity, physiology, genomics and biotechnology. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2019. pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Amotz A, Shaish A, Avron M. The biotechnology of cultivating Dunaliella for production of β-carotene rich algae. Bioresour Technol. 1991;38(2–3):233–235. doi: 10.1016/0960-8524(91)90160-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Amotz A, Polle J, Rao DS. The alga Dunaliella: biodiversity, physiology, genomics and biotechnology. Enfield: Science Publishers; 2009. p. 555. [Google Scholar]

- Borovkov AB, Gudvilovich IN, Memetshaeva OA, Avsiyan AL, Lelekov AS, Novikova TM. Morphological and morphometrical features in Dunaliella salina (Chlamydomonadales, Dunaliellaceae) during the two-phase cultivation mode. Ecologica Montenegrina. 2019;22:157–165. doi: 10.37828/em.2019.22.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borovkov AB, Gudvilovich IN, Avsiyan AL. Scale-up of Dunaliella salina cultivation: from strain selection to open ponds. J Appl Phycol. 2020;32:1545–1558. doi: 10.1007/s10811-020-02104-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borovkov AB, Gudvilovich IN, Avsiyan AL, Memetshaeva OA, Lelekov AS, Novikova TM. Production characteristics of Dunaliella salina at two-phase pilot cultivation (Crimea) Turk J Fish Aquat Sc. 2020;20(5):401–408. doi: 10.4194/1303-2712-v20_5_08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borowitzka MA, Siva CJ. The taxonomy of the genus Dunaliella (Chlorophyta, Dunaliellales) with emphasis on the marine and halophilic species. J Appl Phycol. 2007;19(5):567–590. doi: 10.1007/s10811-007-9171-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borowitzka MA, Vonshak A. Scaling up microalgal cultures to commercial scale. Eur J Phycol. 2017;52(4):407–418. doi: 10.1080/09670262.2017.1365177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chekushkin AA, Gudvilovich IN, Lelekov AS. Production characteristics of Spirulina platensis and Dunaliella salina cultures in the Sevastopol region at the off-season. Issues Mod Algol. 2019;19:96–104. doi: 10.33624/2311-0147-2019-1(19)-96-104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chekushkin AA, Lelekov AS, Gevorgiz RG. Seasonal dynamics of ultimate productivity in horizontal photobioreactor. Russ J Biol Phys. 2020;5(3):405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Wang C, Xu C. Nutritional evaluation of two marine microalgae as feedstock for aquafeed. Aquac Res. 2020;51:946–956. doi: 10.1111/are.14439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva MROB, Moura YAS, Converti A, Porto ALF, Marques DDAV, Bezerra RP. Assessment of the potential of Dunaliella microalgae for different biotechnological applications: a systematic review. Algal Res. 2021;58:102396. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2021.102396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. JModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Campo JA, García-González M, Guerrero MG. Outdoor cultivation of microalgae for carotenoid production: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;74(6):1163–1174. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0844-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz JP, Inostroza C, Acién FG. Scale-up of a Fibonacci-type photobioreactor for the production of Dunaliella salina. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2021;193:88–204. doi: 10.1007/s12010-020-03410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmundson SJ, Huesemann MH. The dark side of algae cultivation: characterizing night biomass loss in three photosynthetic algae, Chlorella sorokiniana, Nannochloropsis salina and Picochlorum sp. Algal Res. 2015;12:470–476. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2015.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emami K, Hack E, Nelson A, Brain CM, Lyne FM, Mesbahi E, Day JG, Caldwell GS. Proteomic-based biotyping reveals hidden diversity within a microalgae culture collection: an example using Dunaliella. Sci Rep. UK. 2015;5(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/srep10036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-González M, Moreno J, Cañavate JP, Anguis V, Prieto A, Manzano C, Florencio FJ, Guerrero MG. Conditions for open-air outdoor culture of Dunaliella salina in southern Spain. J Appl Phycol. 2003;15:177–184. doi: 10.1023/A:1023892520443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths MJ, Garcin C, van Hille RP, Harrison ST. Interference by pigment in the estimation of microalgal biomass concentration by optical density. J Microbiol Meth. 2011;85(2):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudvilovich IN, Borovkov AB. Testing of two-stage cultivation of Dunaliella salina (Teodoresco, 1905) in the Sevastopol region. South Russia Ecol Dev. 2019;14(2):211–220. doi: 10.18470/1992-1098-2019-2-211-220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Highfield A, Ward A, Pipe R, Schroeder DC. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis reveals new diversity of Dunaliella salina from hypersaline environments. J Mar Biol Assoc U K. 2021 doi: 10.1017/S0025315420001319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khadim SR, Singh P, Singh AK, Tiwari A, Mohanta A, Asthana RK. Mass cultivation of Dunaliella salina in a flat plate photobioreactor and its effective harvesting. Bioresour Technol. 2018;270:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers PP, van de Laak CC, Kaasenbrood PS, Lorier J, Janssen M, De Vos RC, Wijffels RH, et al. Carotenoid and fatty acid metabolism in light-stressed Dunaliella salina. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106(4):638–648. doi: 10.1002/bit.22725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelekov AS, Trenkenshu RP. Simplest models of microalgae growth 4. Exponential and linear growth phases of microalgae culture. Ekologiya Morya. 2007;74:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Leliaert F, Verbruggen H, Vanormelingen P, Steen F, López-Bautista JM, Zuccarello GC, De Clerck O. DNA-based species delimitation in algae. Eur J Phycol. 2014;49:179–196. doi: 10.1080/09670262.2014.904524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massyuk NP (1973) Morphology, taxonomy, ecology, geographical distribution of the genus Dunaliella Teod. and perspective for its practical use, 1st edn. Nauk. Dumka Publ., Kiev, p 487 (in Russian)

- Morgulis A, Coulouris G, Raytselis Y, Madden TL, Agarwala R, Schäffer AA. Database indexing for production MegaBLAST searches. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(16):1757–1764. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASA Langley Research Center (LaRC) POWER Project (2021) https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/. Accessed 06 Mar 2021

- Olmos J, Paniagua J, Contreras R. Molecular identification of Dunaliella sp. utilizing the 18S rDNA gene. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2000;30:80–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2000.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos J, Ochoa L, Paniagua-Michel J, Contreras R. DNA fingerprinting differentiation between -carotene hyperproducer strains of Dunaliella from around the world. Saline Syst. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1746-1448-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren A. A hundred years of Dunaliella research: 1905–2005. Saline Syst. 2005;1(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1746-1448-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polle JEW, Jin ES, Ben-Amotz A. The alga Dunaliella revisited: Looking back and moving forward with model and production organisms. Algal Res. 2020;49:01948. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2020.101948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pomroy AJ. Scanning electron microscopy of Heterocapsa minima sp. nov. (Dinophyceae) and its seasonal distribution in the Celtic Sea. Br Phycol J. 1989;24(2):131–135. doi: 10.1080/00071618900650121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preetha K, John L, Subin CS, Vijayan KK. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of Dunaliella (Chlorophyta) from Indian salinas and their diversity. Aquat Biosyst. 2012;8:27. doi: 10.1186/2046-9063-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Science4all (2009) Microscopy and photography. http://science4all.nl/?Microscopy_and_Photography. Accessed 05 Dec 2021

- Shaish A, Avron M, Ben-Amotz A. Effect of inhibitors on the formation of stereoisomers in the biosynthesis of β-carotene in Dunaliella bardawil. Plant Cell Physiol. 1990;31(5):689–696. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a077964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sui Y, Muys M, Vermeir P, D'Adamo S, Vlaeminck SE. Light regime and growth phase affect the microalgal production of protein quantity and quality with Dunaliella salina. Bioresour Technol. 2019;275:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Liu D. Geometric models for calculating cell biovolume and surface area for phytoplankton. J Plankton Res. 2003;25(11):1331–1346. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbg096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Supamattaya K, Kiriratnikom S, Boonyaratpalin M, Borowitzka L. Effect of a Dunaliella extract on growth performance, health condition, immune response and disease resistance in black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) Aquaculture. 2005;248(1–4):207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terez EI, Terez GA, Kozak AV, Kuzmin SV, Dolgii SO. The study of atmospheric optical parameters according to multiyear photometric observations of the sun in Crimea. Bull Crime Astrophys Obs. 2012;108(1):146–157. doi: 10.3103/S0190271712010214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf L, Cummings T, Müller K, Reppke M, Volkmar M, Weuster-Botz D. Production of β-carotene with Dunaliella salina CCAP19/18 at physically simulated outdoor conditions. Eng Life Sci. 2021;21(3–4):115–125. doi: 10.1002/elsc.202000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Dejtisakdi W, Kermanee P, Ma C, Arirob W, Sathasivam R, Juntawong N. Outdoor cultivation of Dunaliella salina KU 11 using brine and saline lake water with raceway ponds in northeastern Thailand. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2017;64(6):938–943. doi: 10.1002/bab.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Ibrahim IM, Harvey PJ. The influence of photoperiod and light intensity on the growth and photosynthesis of Dunaliella salina (Chlorophyta) CCAP 19/30. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;106:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J Comput Biol. 2000;7(1–2):203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]